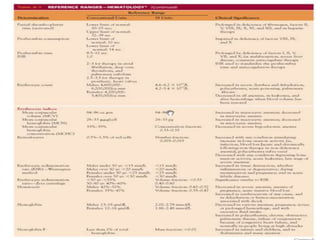

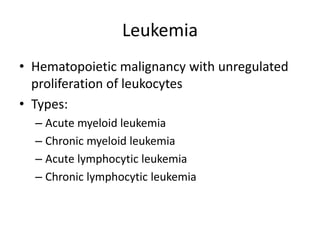

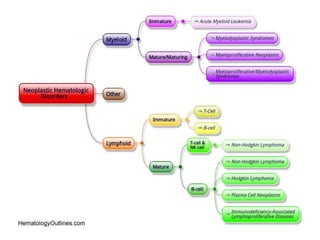

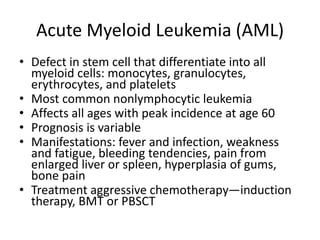

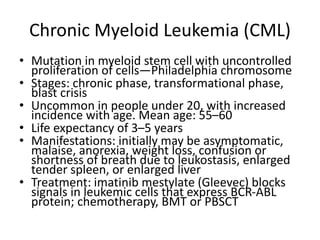

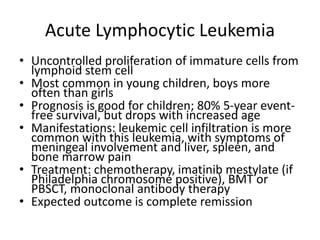

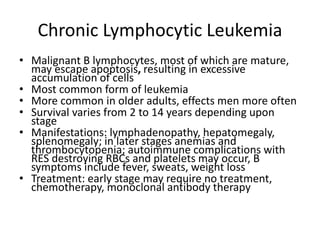

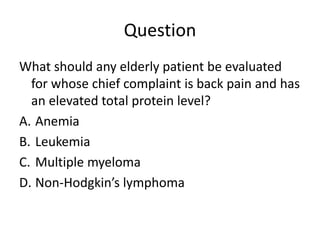

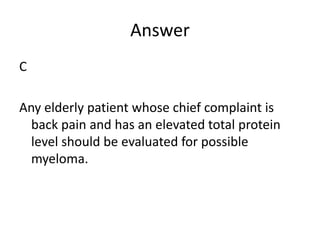

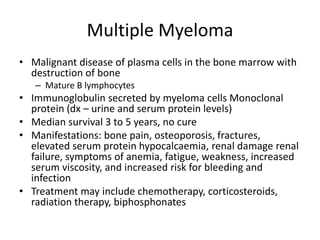

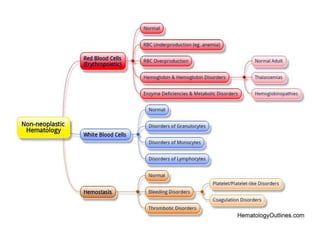

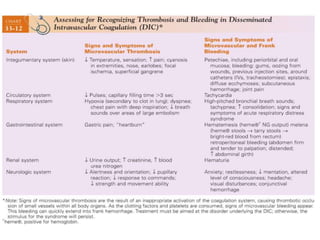

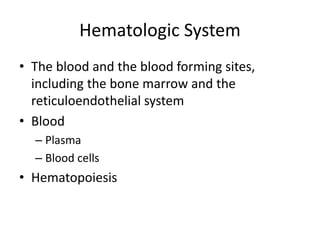

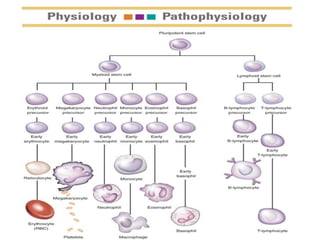

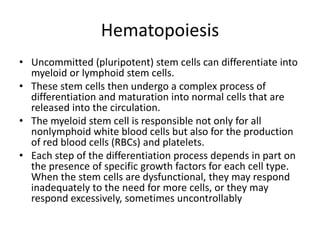

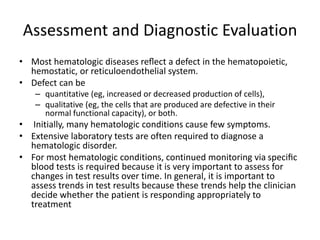

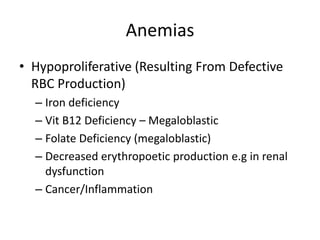

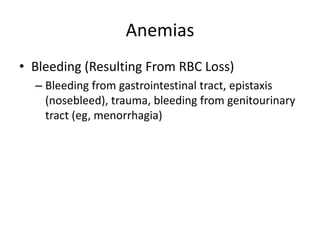

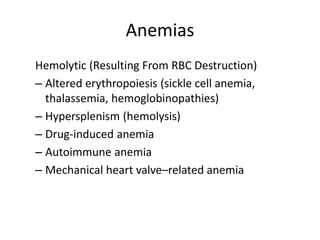

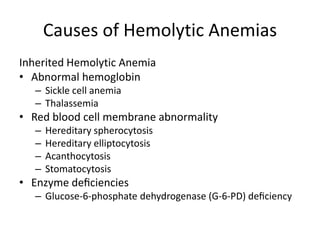

This document provides an in-depth overview of hematologic disorders, focusing on the assessment and management of conditions like anemia, leukemias, and myelodysplastic syndromes. It outlines key processes such as hematopoiesis and hemostasis, differentiates types of anemia based on their causes, and discusses nursing care principles for patients with these disorders. Additionally, it explains the diagnostic evaluation and medical management of various hematologic conditions, emphasizing the importance of ongoing monitoring and individualized patient care.

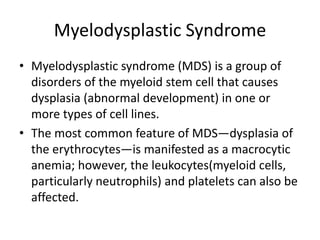

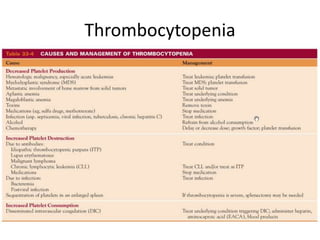

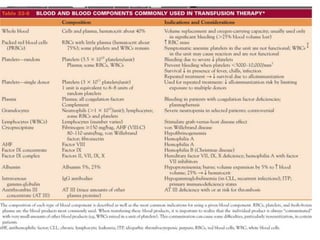

![BLOOD

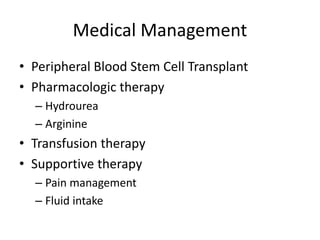

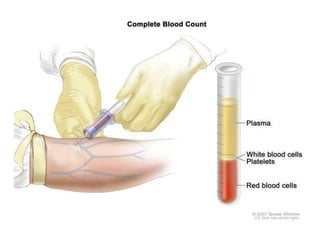

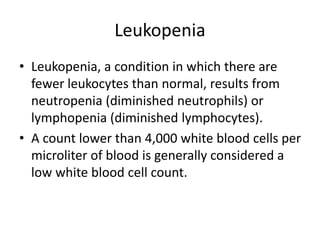

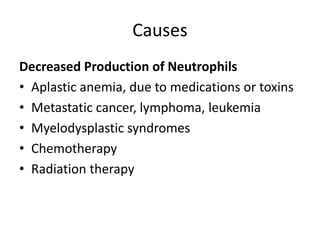

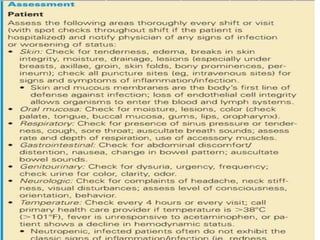

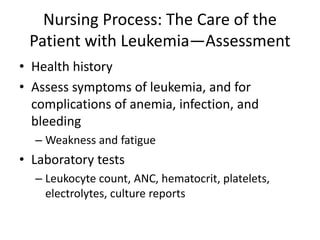

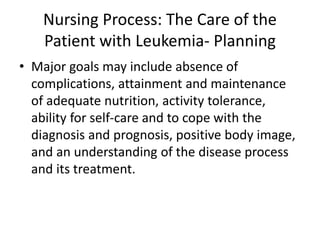

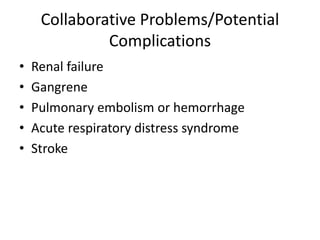

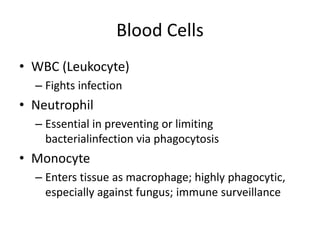

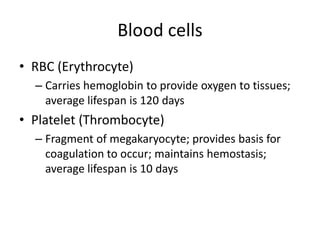

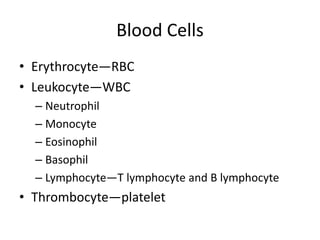

• The cellular component of blood consists of

three primary cell types:

– erythrocytes(red blood cells[RBCs], red cells),

– leukocytes(white blood cells [WBCs]),

– thrombocytes (platelets).T](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-240422055844-6744cedc/85/4-0-HEMATOLO-DISORDER-2-pptx-3-320.jpg)

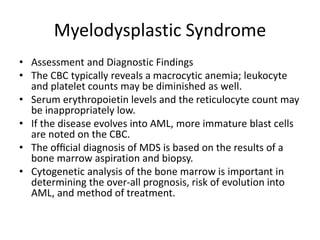

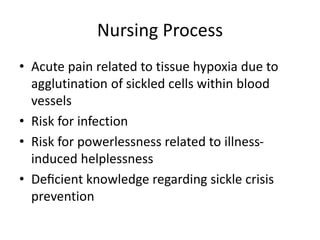

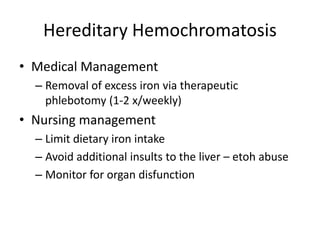

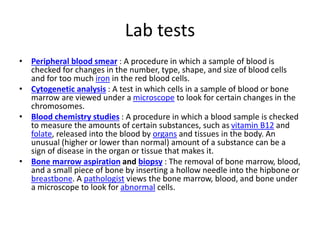

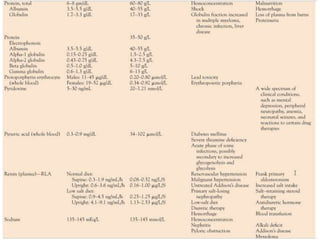

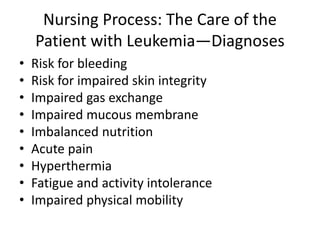

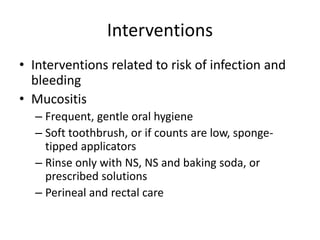

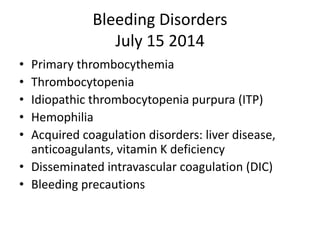

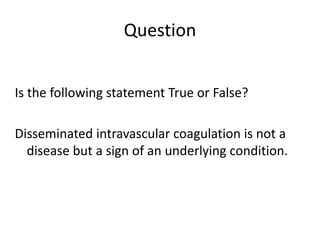

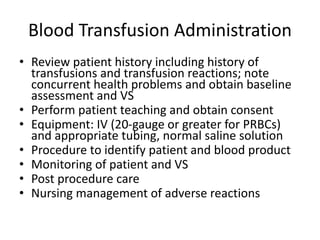

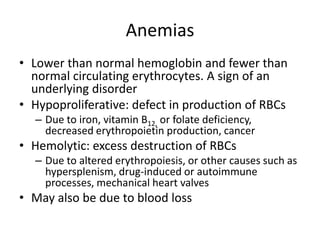

![Assessment and Diagnostic Findings

• hemoglobin, hematocrit, reticulocyte count,

and RBC indices, particularly the mean

corpuscular volume(MCV) and red cell

distribution width (RDW)

• Iron studies (serum iron level, total iron-

binding capacity [TIBC], percent saturation,

and ferritin), as well as serum vitamin B12and

folate levels](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/4-240422055844-6744cedc/85/4-0-HEMATOLO-DISORDER-2-pptx-32-320.jpg)