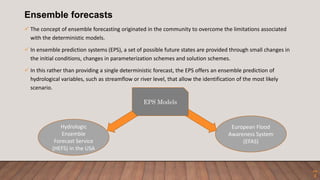

This document presents a seminar on improving flood forecasting in India. It discusses types of floods and their causes and impacts. It then covers current methods of flood forecasting, including deterministic models, data-driven models, and ensemble forecasts. Past efforts in India are reviewed through case studies applying models like ANN to rivers. Challenges are outlined such as limited data availability. The document concludes more investment is needed in India to develop efficient forecasting systems with longer lead times to better protect lives from flooding.