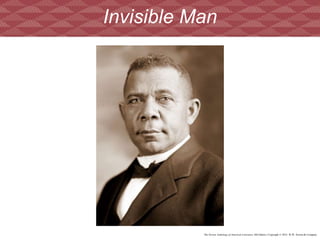

Ralph Ellison was born in Oklahoma in 1914 and attended Tuskeegee Institute on a scholarship where he studied music and played trumpet. He moved to New York City in 1936 where he met novelist Richard Wright and began writing his novel Invisible Man in 1945, which was published in 1952. Invisible Man tells the story of an unnamed narrator who feels invisible in society due to the color of his skin and explores themes of individualism, identity, and racism in America.

![The Norton Anthology of American Literature, 8th Edition | Copyright © 2012 W.W. Norton & Company

“[O]ur life is a war and I have been a traitor

all my born days, a spy in the enemy’s

country . . . Live with your head in the lion’s

mouth. I want you to overcome ’em with

yesses, undermine ’em with grins, agree ’em

to death and destruction, let ’em swoller you

till they vomit or bust wide open.”

Invisible Man](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/3naal8voleellisonfinal-160821144219/85/2130_American-Lit-Module-3_Ralph-Ellison-4-320.jpg)