The document provides an overview and plan for a lecture on database management systems. Key points include:

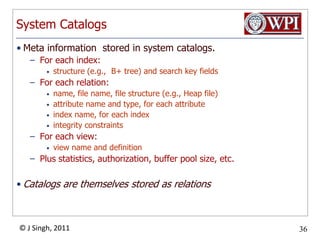

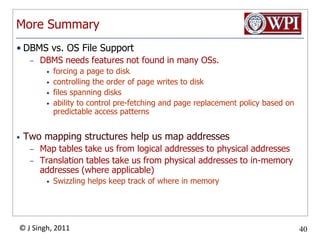

- By the second break, the lecture will cover storage hierarchies, secondary storage management, and system catalogs.

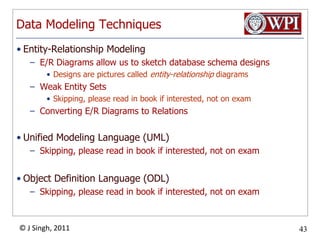

- After the second break, the topics will include data modeling and storage hierarchies.

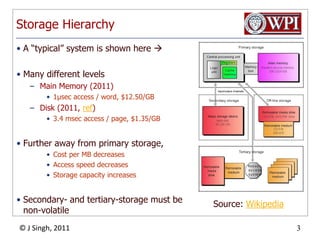

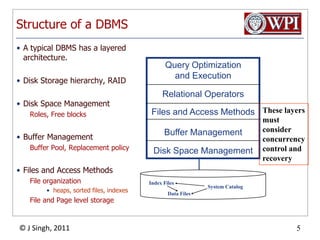

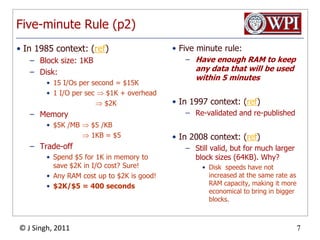

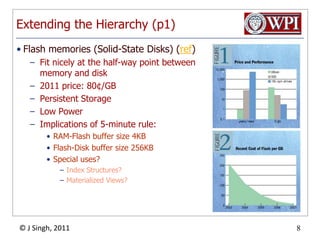

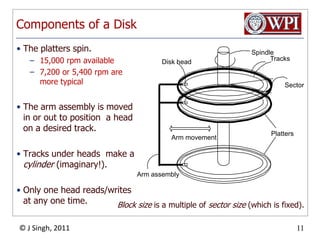

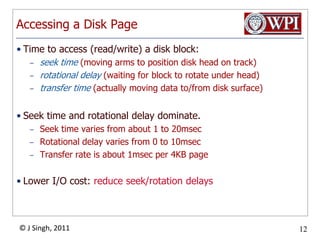

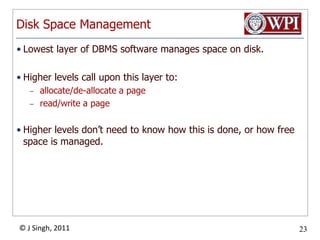

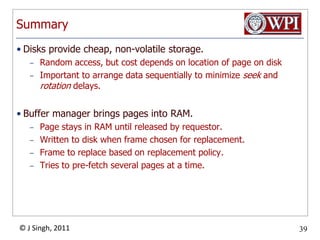

- Storage hierarchies involve multiple storage levels from main memory to disk and beyond. The cost and performance of each level differs.

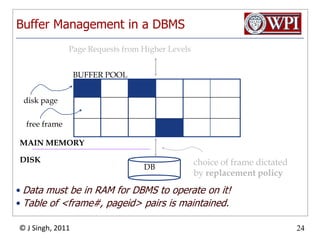

- Techniques like caching aim to keep frequently used data in faster storage levels like memory.