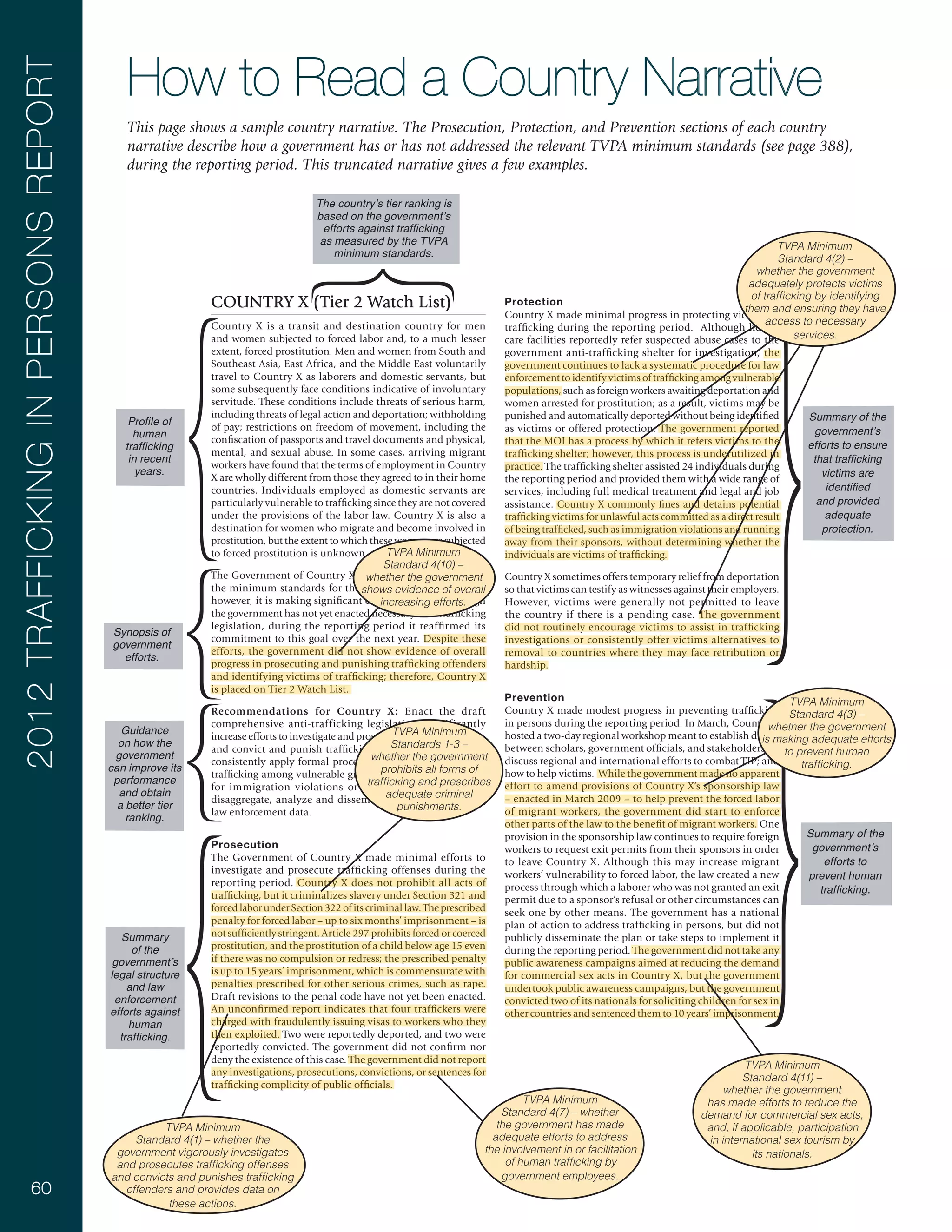

The document provides information about human trafficking in Country X. It notes that Country X is a transit and destination country for forced labor and sex trafficking. Victims are men and women from various countries in Asia and Africa who come to Country X voluntarily for work but then face conditions of involuntary servitude, including threats, withheld pay, restricted movement, and abuse. The government was placed on Tier 2 Watch List for failing to show overall progress in prosecuting traffickers and identifying victims, despite making some efforts to address trafficking, such as hosting workshops. Recommendations are provided for how the government can strengthen its anti-trafficking laws and protections for victims.

![CHINA

119

internal and foreign victims of trafficking throughout the

country, but continued to train managers of multipurpose

shelters.

The government continued drafting the 2012 National

Plan of Action for anti-trafficking efforts, which should be

released in December 2012, in consultation with international

organizations; at the time of publication of this report, the

details of the draft plan were not yet public. In March 2012, the

government released data about a variety of crimes, some of

them purportedly human trafficking, reflecting an expanded

definition of trafficking that included illegal adoption and

crimes of abduction. Thus, it is impossible to discern what

efforts the Chinese government has undertaken to combat

trafficking. The government’s crackdown on prostitution

and child abduction reportedly included rescuing victims of

trafficking and punishing trafficking offenders. Nonetheless

China continues to conflate trafficking with non-trafficking

crimes such as fraudulent child adoption, rendering the full

extent of the government’s anti-trafficking efforts unclear.

Despite basic efforts to investigate some cases of forced labor

that generated a high degree of media attention and the

plans to hire thousands of labor inspectors, the impact of

these measures on addressing the full extent of trafficking

for forced labor throughout the country remains unclear. The

government took no discernible steps to address the role that

its birth limitation policy plays in fueling human trafficking in

China, with gaping gender disparities resulting in a shortage

of female marriage partners. The government failed to take

any steps to change the policy; and in fact, according to the

Chinese government, the number of foreign female trafficking

victims in China rose substantially in the reporting period. The

Director of the Ministry of Public Security’s Anti-Trafficking

Task Force stated in the reporting period that “[t]he number

of foreign women trafficked to China is definitely rising”

and that “great demand from buyers as well as traditional

preferences for boys in Chinese families are the main culprits

fueling trafficking in China.” China continued to lack a formal,

nationwide procedure to systematically identify victims of

trafficking; however, in the past the government issued a

national directive instructing law enforcement officers to treat

people in prostitution as victims of trafficking until proven

otherwise and prohibited police from closing any trafficking-

related cases until the victims were located. Victims may be

punished for unlawful acts that were a direct result of their

being trafficked – for instance, violations of prostitution or

immigration and emigration controls. Chinese authorities

continue to detain and forcibly deport North Korean trafficking

victims who face punishment upon their return to North Korea

for unlawful acts that were sometimes a direct result of being

trafficked, and these North Koreans face severe punishment,

which may include death, upon being forcibly repatriated to

North Korea by China.

P

Recommendations for China:Draft and enact comprehensive

anti-trafficking legislation in line with the 2000 UN TIP

Protocol; cease pre-trial detention of forced labor and sex

trafficking victim advocates and activists; seek the assistance

of the international community to close “re-education through

labor” camps; provide disaggregated data on efforts to

investigate and prosecute human trafficking; vigorously

investigate and prosecute government corruption and

complicity cases, and ensure officials are held to the highest

standards of the law; seek the assistance of the international

community to bring China’s trafficking definition in line with

the 2000 UN TIP Protocol, including separating out non-

trafficking crimes such as illegal adoption, abduction, and

smuggling; publish the national plan of action to address all

forms of trafficking, including forced labor and the trafficking

of men; provide data on funds spent on trafficking and law

enforcement efforts, including separating out non-trafficking

crimes such as abduction, illegal adoption, and smuggling;

prohibit punishment clauses in employment contracts of

workers, both those working domestically and those working

abroad; increase transparency of government efforts to combat

trafficking; institute effective victim identification procedures

among vulnerable groups, such as migrant workers, the

mentally disabled, women arrested for prostitution, and

children, and ensure these populations are not prosecuted

for crimes committed as a result of trafficking; expand available

trafficking shelters and resources, including counseling,

medical, reintegration, and rehabilitative assistance to all

trafficking victims, including male and forced labor victims;

assist Chinese citizen victims of trafficking found abroad;

cease detaining, punishing, and forcibly repatriating North

Korean trafficking victims; provide legal alternatives to foreign

victims’ removal to countries in which they would face

hardship or retribution; educate the public to reduce demand

for, and vigorously investigate and prosecute, child sex tourism

cases.

Prosecution

The government’s anti-trafficking efforts continued to focus

on transnational trafficking of foreign women and girls to

China and the forced prostitution of Chinese girls and women

within the country. The amount and degree of complicity by

government officials in trafficking offences remained difficult

to ascertain. The government did not report efforts to combat

trafficking facilitated by government authorities.

Article 240 of China’s criminal code prohibits “abducting and

trafficking of women or children,” but does not adequately

define these concepts. Article 358 prohibits forced prostitution,

which is punishable by five to 10 years’ imprisonment.

Prescribed penalties under these statutes range from five

years’ imprisonment to death sentences, which are sufficiently

stringent and commensurate with those prescribed for other

serious crimes, including rape. Article 244 of the Chinese

Criminal Code prohibits “forcing workers to labor,” punishable

by three to 10 years’ imprisonment and a fine, and expands

culpability to those who also recruit, transport, or assist

in “forcing others to labor.” However, it remains unclear

whether, under Chinese law, children under the age of 18 in

prostitution are victims of trafficking regardless of whether

force is involved. In addition, it remains unclear whether these

Chinese laws prohibit the use of common non-physical forms

of coercion, such as threats and debt bondage, as a form of

“forcing workers to labor” or “forced prostitution” and whether

acts such as recruiting, providing, or obtaining persons for

compelled prostitution are covered. While trafficking crimes

could perhaps be prosecuted under general statutes related

to fraud and deprivation of liberty, authorities did not report](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/22012countryprofilesa-c-130506125456-phpapp02/85/2-7-Trafficking-Report-2012-country-profiles-a-c-60-320.jpg)