This document provides an overview of the book "Development Economics" by Debraj Ray. It discusses the contents and structure of the book, which provides an introduction to development economics through 18 chapters. The book aims to make the large literature on development economics accessible to students with training in basic economic theory. It covers topics such as economic growth, inequality, poverty, population growth, structural transformation, rural and urban development, and international trade. The preface provides guidance on using the book for single-semester or year-long courses in development economics.

![Chapter 1

Introduction

I invite you to study what is surely the most important and

perhaps the most complex of all economic issues: the

economic transformation of those countries known as the

developing world. A definition of “developing countries”

is problematic and, after a point, irrelevant.1 The World

Development Report (World Bank [1996]) employs a

threshold of $9,000 per capita to distinguish between what it

calls high-income countries and low- and middle-

income countries: according to this classification, well over 4.5

billion of the 5.6 billion people in the world today

live in the developing world of “low- and middle-income

countries.” They earn, on average, around $1,000 per

capita, a figure that is worth contrasting with the yearly

earnings of the average North American or Japanese

resident, which are well above $25,000. Despite the many

caveats and qualifications that we later add to these

numbers, the ubiquitous fact of these astonishing disparities

remains.

There is economic inequality throughout the world, but much of

that is, we hope, changing. This book puts

together a way of thinking about both the disparities and the

changes.

There are two strands of thought that run through this text.

First, I move away from (although do not entirely

abandon) a long-held view that the problems of all developing

countries can be understood best with reference to

the international environment of which they are a part.2

According to this view, the problems of underdevelopment](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-21-320.jpg)

![international

organizations such as the World Bank. A composite index that

goes beyond per capita income is described in Human

Development Report

(United Nations Development Programme [1995]). There is

substantial agreement across all these classifications.

2 This view includes not only the notion that developing

countries are somehow hindered by their exposure to the

developed world,

18

epitomized in the teachings of dependencia theorists, but also

more mainstream concerns regarding the central role of

international

organizations and foreign assistance.

3 Case studies, which are referred to as boxes, will be set off

from the text by horizontal rules.

19

Chapter 2

Economic Development: Overview

By the problem of economic development I mean simply the

problem of accounting for the observed pattern, across countries

and

across time, in levels and rates of growth of per capita income.

This may seem too narrow a definition, and perhaps it is, but

thinking about income patterns will necessarily involve us in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-27-320.jpg)

![thinking about many other aspects of societies too, so I would

suggest

that we withhold judgement on the scope of this definition until

we have a clearer idea of where it leads us.

—R. E. Lucas [1988]

[W]e should never lose sight of the ultimate purpose of the

exercise, to treat men and women as ends, to improve the human

condition, to enlarge people’s choices. . . . [A] unity of interests

would exist if there were rigid links between economic

production

(as measured by income per head) and human development

(reflected by human indicators such as life expectancy or

literacy, or

achievements such as self-respect, not easily measured). But

these two sets of indicators are not very closely related.

—P. P. Streeten [1994]

2.1. Introduction

Economic development is the primary objective of the majority

of the world’s nations. This truth is accepted almost

without controversy To raise the income, well-being, and

economic capabilities of peoples everywhere is easily the

most crucial social task facing us today. Every year, aid is

disbursed, investments are undertaken, policies are

framed, and elaborate plans are hatched so as to achieve this

goal, or at least to step closer to it. How do we identify

and keep track of the results of these efforts? What

characteristics do we use to evaluate the degree of

“development” a country has undergone or how “developed” or

“underdeveloped” a country is at any point in time?

In short, how do we measure development?

The issue is not easy to resolve. We all have intuitive notions of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-28-320.jpg)

![Per capita incomes are, of course, expressed in takas, reales,

yuan, and in the many other world currencies. To

facilitate comparison, each country’s income (in local currency)

is converted into a common currency (typically

U.S. dollars) and divided by that country’s population to arrive

at a measure of per capita income. This conversion

scheme is called the exchange rate method, because it uses the

rates of exchange between the local and the common

currencies to express incomes in a common unit. The World

Development Report (see, e.g., World Bank [1996])

contains such estimates of GNP per capita by country. By this

yardstick, the world produced $24 trillion of output

in 1993. About 20% of this came from low- and middle-income

developing countries—a pittance when we see that

these countries housed 85% of the world’s population at that

time. Switzerland, the world’s richest country under

this system of measurement, enjoyed a per capita income close

to 400 times that of Tanzania, the world’s poorest.

21

Figure 2.1. Per capita income and population for selected

countries.

Figure 2.1 displays per capita income figures for selected

countries. The figure contrasts per capita incomes in

different countries with the populations of these countries. No

comment is necessary.

The disparities are enormous, and no amount of fine-tuning in

measurement methods can get rid of the stark

inequalities that we live with. Nevertheless, both for a better

understanding of the degree of international variation

that we are talking about and for the sake of more reliable](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-33-320.jpg)

![Figure 2.2. The world’s eight largest economies: exchange rate

and PPP calculations. Source: World Development Report

(World Bank

[1995]).

Figure 2.2 shows how the eight largest economies change when

we move from exchange rates to PPP calculations.

Although the Summers-Heston data are useful for real

comparisons, remember that exchange rate-based data are the

appropriate ones

to use for international financial transactions and capital flows.

Briefly (see box for more details), international prices are

constructed for an enormous basket of goods and

services by averaging the prices (expressed, say, in dollars) for

each such good and service over all different

countries. National income for a country is then estimated by

valuing its outputs at these international prices. In this

way, what is maintained, in some average sense, is parity in the

purchasing power among different countries. Thus

we call such estimates PPP estimates, where PPP stands for

“purchasing power parity.”

PPP estimates of per capita income go some way toward

reducing the astonishing disparities in the world

distribution of income, but certainly not all the way. For an

account of how the PPP estimates alter the distribution

of world income, consult Figure 2.3.

The direction of change is quite clear and, from the foregoing

discussion, only to be expected. Measured in PPP

dollars, developing countries do better relative to U.S. per

capita GNP, although the fractions are still small, to be

sure. This situation reflects the fact that domestic prices are not

captured adequately by using exchange-rate](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-39-320.jpg)

![conversions, which apply correctly only to a limited set of

traded goods.

(3) There are other subtle problems of measurement. GNP

measurement, even when it accounts for the

exchange-rate problem, uses market prices to compare apples

and oranges; that is, to convert highly disparate goods

into a common currency. The theoretical justification for this is

that market prices reflect people’s preferences as

well as relative scarcities. Therefore such prices represent the

appropriate conversion scale to use. There may be

several objections to this argument. Not all markets are

perfectly competitive; neither are all prices fully flexible.

24

We have monopolies, oligopolistic competition, and public

sector companies6 that sell at dictated prices. There is

expenditure by the government on bureaucracy, on the military,

or on space research, whose monetary value may

not reflect the true value of these services to the citizens.

Moreover, conventional measures of GNP ignore costs that

arise from externalities—the cost of associated pollution,

environmental damage, resource depletion, human

suffering due to displacement caused by “development projects”

such as dams and railways, and so forth. In all of

these cases, prevalent prices do not capture the true marginal

social value or cost of a good or a service.

Figure 2.3. PPP versus exchange rate measures of GDP for

ninety-four countries, 1993. Source: World Development Report

(World Bank

[1995]).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-40-320.jpg)

![All these problems can be mended, in principle, and

sophisticated measures of GDP do so to a large extent.

Distortions in prices can be corrected for by imputing and using

appropriate “shadow prices” that capture true

marginal values and costs. There is a vast literature, both

theoretical and empirical, that deals with the concepts and

techniques needed to calculate shadow prices for commodities.

An estimated “cost of pollution” is often deducted in

some of the measures of net GDP, at least in industrialized

economies. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware of

these additional problems.

With this said, let us turn to a brief account of recent historical

experience.

2.2.2. Historical experience

Over the period 1960–85, the richest 5% of the world’s nations

averaged a per capita income that was about

twenty-nine times the corresponding figure for the poorest 5%.

As Parente and Prescott [1993] quite correctly

observed, interstate disparities within the United States do not

even come close to these international figures. In

1985, the richest state in the United States was Connecticut and

the poorest was Mississippi, and the ratio of per

capita incomes worked out at around 2!

Of course, the fact that the richest 5% of countries bear

approximately the same ratio of incomes (relative to the

poorest 5%) over this twenty-five year period suggests that the

entire distribution has remained stationary. Of

greatest interest, and continuing well into the nineties, is the

meteoric rise of the East Asian economies: Japan,

Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, Malaysia,

Indonesia, and, more recently, China. Over the period

1965–90, the per capita incomes of the aforementioned eight](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-41-320.jpg)

![East Asian economies (excluding China) increased at

an annual rate of 5.5%. Between 1980 and 1993, China’s per

capita income grew at an annual rate of 8.2%, which

is truly phenomenal. For the entire data set of 102 countries

studied by Parente and Prescott, per capita growth

averaged 1.9% per year over the period 1960–85.

In contrast, much of Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa

languished during the 1980s. After relatively high

25

rates of economic expansion in the two preceding decades,

growth slowed to a crawl, and in many cases there was

no growth at all. Morley’s [1995] study observed that in Latin

America, per capita income fell by 11% during the

1980s, and only Chile and Colombia had a higher per capita

income in 1990 than they did in 1980. It is certainly

true that such figures should be treated cautiously, given the

extreme problems of accurate GNP measurement in

high-inflation countries, but they illustrate the situation well

enough.

Similarly, much of Africa stagnated or declined during the

1980s. Countries such as Nigeria and Tanzania

experienced substantial declines of per capita income, whereas

countries such as Kenya and Uganda barely grew in

per capita terms.

Diverse growth experiences such as these can change the face of

the world in a couple of decades. One easy

way to see this is to study the “doubling time” implicit in a

given rate of growth; that is, the number of years it takes

for income to double if it is growing at some given rate. The](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-42-320.jpg)

![calculation in the footnote7 reveals that a good

approximation to the doubling time is seventy divided by the

annual rate of growth expressed in percentage terms.

Thus an East Asian country growing at 5% per year will double

its per capita income every fourteen years! In

contrast, a country growing at 1% per year will require seventy

years. Percentage growth figures look like small

numbers, but over time, they add up very fast indeed.

The diverse experiences of countries demand an explanation,

but this demand is ambitious. Probably no single

explanation can account for the variety of historical experience.

We know that in Latin America, the so-called debt

crisis (discussed more in Chapter 17) triggered enormous

economic hardship. In sub-Saharan Africa, low per capita

growth rates may be due, in large measure, to unstable

government and consequent infrastructural breakdown, as

well as to recent high rates of population increase (on this, see

Chapters 3 and 9). The heady successes of East Asia

are not fully understood, but a conjunction of farsighted

government intervention (Chapters 17), a relatively equal

domestic income distribution (Chapters 6 and 7), and a vigorous

entry into international markets played an

important role. As you may have noted from the occasional

parentheses in this paragraph, we will take up these

topics, and many others, in the chapters to come.

Thus it is quite possible for the world distribution of income to

stay fairly constant in relative terms, while at the

same time there is plenty of action within that distribution as

countries climb and descend the ladder of relative

economic achievement. Indeed, the few countries that we have

cited as examples are no exceptions. Figure 2.4

contains the same exercise as Chart 10 in Parente and Prescott

[1993]. It shows the number of countries that

experienced changes in income (relative to that of the United](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-43-320.jpg)

![States) of different magnitudes over the years 1960–

85.

Figure 2.4 indicates two things. First, a significant fraction

(well over half) of countries changed their position

relative to the United States by an average of one percentage

point or more per year, over the period 1960–85.

Second, the figure also indicates that there is a rough kind of

symmetry between changes upward and changes

downward, which partly accounts for the fact that you don’t see

much movement in the world distribution taken as a

whole. This observation is cause for much hope and some

trepidation: the former, because it tells us that there are

probably no traps to ultimate economic success, and the latter,

because it seems all too easy to slip and fall in the

process. Economic development is probably more like a

treacherous road, than a divided highway where only the

privileged minority is destined to ever drive the fast lane.

26

Figure 2.4. Annual percentage change in PPP income of

different countries relative to U.S. levels, 1960–85. Source:

Penn World Tables .

This last statement must be taken with some caution. Although

there appears to be no evidence that very poor

countries are doomed to eternal poverty, there is some

indication that low incomes are very sticky. Even though we

will have much more to say about the hypothesis of ultimate

convergence of all countries to a common standard of

living (see Chapters 3–5), an illustration may be useful at this

stage. Quah [1993] used per capita income data to

construct “mobility matrices” for countries. To understand how](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-44-320.jpg)

![particular category have a high probability of staying right

there. Conversely, a matrix that has the same numbers in every

entry (which must be 20 in our 5 × 5 case, given that

the numbers must sum to 100 along each row) shows an

extraordinarily high rate of mobility. Regardless of the

starting point in 1962, such a matrix will give you equal odds of

being in any of the categories in 1984.

27

Figure 2.5. The income mobility of countries, 1962–84. Source:

Quah [1993] .

With these observations in mind, continue to stare at Figure 2.5.

Notice that middle-income countries have far

greater mobility than either the poorest or the richest countries.

For instance, countries in category 1 (between half

the world average and the world average) in 1962 moved away

to “right” and “left”: less than half of them remained

where they were in 1962. In stark contrast to this, over three-

quarters of the poorest countries (category 1/4) in

1962 remained where they were, and none of them went above

the world average by 1984. Likewise, fully 95% of

the richest countries in 1962 stayed right where they were in

1984.8 This is interesting because it suggests that

although everything is possible (in principle), a history of

underdevelopment or extreme poverty puts countries at a

tremendous disadvantage.

This finding may seem trite. Poverty should feed on itself and

so should wealth, but on reflection you will see

that this is really not so. There are certainly many reasons to

think that historically low levels of income may be

advantageous to rapid growth. New technologies are available](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-46-320.jpg)

![inequality in those countries.

Figure 2.6 also plots tentative trends in these shares as we move

from poor to rich countries. There appears to be

a tendency for the share of the richest 20% to fall, rather

steeply in fact, as we cross the $8,000 per capita income

threshold (1993 PPP). However, there is also a distinct tendency

for this share to rise early on in the income scale

(mentally shut out the patch after $8,000 and look at the

diagram again). The overall tendency, then, is for the share

of the richest 20% to rise and then fall over the cross section of

incomes represented in the diagram. The share of

the poorest 40% displays the opposite relationship, although it

is somewhat less pronounced. At both extremes of

the income scale, the share is relatively high, and falls to a

minimum around the middle (in the cluster represented

by $4,000–9,000 of per capita income).

29

Figure 2.6. Income shares of poorest 40% and richest 20% for

fifty-seven countries arranged in order of increasing per capita

income (PPP).

Source: World Development Report (World Bank [1995]) and

Deininger and Squire [1996a].

The two trends together suggest, very tentatively indeed, that

inequality might rise and then fall as we move

from lower to higher incomes. This is the essence of a famous

hypothesis owing to Kuznets [1955] that is known as

the inverted U (referring to the shape traced by rising and then

falling inequality). We will take a closer look at this

relationship in Chapter 7. For now, nothing is really being said

about how inequality in a single country changes](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-50-320.jpg)

![higher levels of per capita income, economic gains tend to be

distributed more equally—the poorest quintiles now

gain in income share.

Table 2.1. Shares of poorest 40% and richest 20% for selected

countries.

30

Source: World Development Report (World Bank [1995]) and

Deininger and Squire [1996a].

It is worth noting (and we will say this again in Chapter 7) that

there is no inevitability about this process.

Countries that pursue policies of broad-based access to

infrastructure and resources, such as health services and

education, will in all likelihood find that economic growth is

distributed relatively equally among the various groups

in society. Countries that neglect these features will show a

greater tendency toward inequality. Indeed, matters are

actually more complicated than this. These policies may in turn

affect the overall rate of growth that a country can

sustain. Although many of us might want to believe that equity

and growth go hand in hand, this may well turn out

to be not true, at least in some situations. The need to discuss

this crucial interaction cannot be overemphasized.

The combination of low per capita incomes and the unequal

distribution of them means that in large parts of the

developing world, people might lack access to many basic

services: health, sanitation, education, and so on. The

collection of basic indicators that makes up the nebulous

concept of progress has been termed human development,

and this is what we turn to next.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-52-320.jpg)

![GDP of $2,170. The poorest 40% of the population earn 21% of

the total income. These overall figures are similar

to those of Sri Lanka, but Pakistan has a life expectancy of only

62 and an infant mortality rate of ninety-one per

thousand, five times that of Sri Lanka. The literacy rate for

Pakistan was only 36% in 1992—significantly less than

half that of Sri Lanka. Clearly, government policies, such as

those concerning education and health, and the public

demand for such policies, play significant roles.

Table 2.2. Shares of poorest 40% and richest 20% for Sri Lanka

and Guatemala.

Source: World Development Report (World Bank [1995]) and

Deininger and Squire [1996].

Table 2.3. Indicators of “human development” for Sri Lanka and

Guatemala.

Source: Human Development Report (United Nations

Development Programme [1995]).

Note: All data are for 1992, except for access to safe water,

which is the 1988–93 average.

2.4.2. An index of human development

32

Many of the direct physical symptoms of underdevelopment are

easily observable and independently

measurable. Undernutrition, disease, illiteracy—these are

among the stark and fundamental ills that a nation would

like to remove through its development efforts. For quite some

time now, international agencies (like the World

Bank and the United Nations) and national statistical surveys](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-55-320.jpg)

![have been collecting data on the incidence of

malnutrition, life expectancy at birth, infant mortality rates,

literacy rates among men and women, and various other

direct indicators of the health, educational, and nutritional

status of different populations.

As we have seen, a country’s performance in terms of income

per capita might be significantly different from

the story told by these basic indicators. Some countries,

comfortably placed in the “middle-income” bracket,

nevertheless display literacy rates that barely exceed 50%,

infant mortality rates close to or exceeding one hundred

deaths per thousand, and undernourishment among a significant

proportion of the population. On the other hand,

there are instances of countries with low and modestly growing

incomes, that have shown dramatic improvements in

these basic indicators. In some categories, levels comparable to

those in the industrialized nations have been

reached.

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has

published the Human Development Report since

1990. One objective of this Report is to coalesce some of the

indicators that we have been discussing into a single

index, which is known as the human development index (HDI).

This is not the first index that has tried to put

various socioeconomic indicators together. A forerunner is

Morris’ “physical quality of life index” (Morris [1979]),

which created a composite index from three indicators of

development: infant mortality, literacy, and life

expectancy conditional on reaching the age of 1.

The HDI has three components as well. The first is life

expectancy at birth (this will indirectly reflect infant and

child mortality).11 The second is a measure of educational

attainment of the society. This measure is itself a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-56-320.jpg)

![for themselves to express the idea that per capita income is a

powerful correlate of development, no matter how

broadly we conceive of it. Thus we must begin, and we do so,

with a study of how per capita incomes evolve in

countries. This is the subject of the theory of economic

growth—a topic that we take up in detail in the chapters to

come.

34

Figure 2.7. Per capita income and life expectancy for

developing countries. Source: World Development Report

(World Bank [1995]) and

Human Development Report (United Nations Development

Programme [1995]).

A further point needs to be stressed. By looking at the actual

levels of achievement in each of these indicators,

rather than just the ranking across countries that they induce, I

have actually made life more difficult for the

argument in favor of per capita income. In an influential book,

Dasgupta [1993] showed that per capita income is

correlated even more highly with other indicators of

development if we consider ranks rather than cardinal

measures. In other words, if we rank countries according to

their per capita GDP levels and then compute similar

ranks based on some other index (such as adult literacy, child

mortality, etc.), then we find a high degree of

statistical correspondence between the two sets of ranks if the

set of countries is sufficiently large and wide ranging.

Because I have already carried out cardinal comparisons, I will

skip a detailed discussion of these matters and

simply refer you to Dasgupta’s study for a more thorough

reading.16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-61-320.jpg)

![35

Figure 2.8. Per capita income and adult literacy rates for

developing countries. Source: World Development Report

(World Bank [1995]) and

Human Development Report (United Nations Development

Programme [1995]).

The point of this section is not to discredit human development,

but only to show that we must not necessarily

swing our opinions to the other extreme and disregard per capita

income altogether. To be more emphatic, we must

take per capita income very seriously, and it is in this spirit that

we can appreciate the seemingly narrow quotation

from Robert Lucas at the beginning of this chapter.

To complete this delicate balancing act, note finally that the

relationship between per capita income and the

other indicators is strong but far from perfect (otherwise the

data would all lie on some smooth curve linking the

two sets of variables). The imperfect nature of the relationship

is just a macroreflection of what we saw earlier with

countries such as Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Guatemala. Inclusion

of the distribution of per capita income would add

to this fit, but even then matters would remain undecided: social

and cultural attitudes, government policy, and the

public demands for such policies, all would continue to play

their role in shaping the complex shell of economic

development. Thus it is only natural that we concentrate on

economic growth and then move on to other pressing

matters, such as the study of income distribution and the

operation of various markets and institutions.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-62-320.jpg)

![36

Figure 2.9. Per capita income and infant mortality rates for

developing countries. Source: World Development Report

(World Bank [1995])

and Human Development Report (United Nations Development

Programme [1995]).

2.5. Some structural features

Our final objective in this chapter is to provide a quick idea of

the structural characteristics of developing countries.

We will examine these characteristics in detail later in the book.

2.5.1. Demographic characteristics

Very poor countries are characterized by both high birth rates

and high death rates. As development proceeds,

death rates plummet downward. Often, birth rates remain high,

before they finally follow the death rates on their

downward course. In the process, a gap opens up (albeit

temporarily) between the birth and death rates. This leads

to high population growth in developing countries. Chapter 9

discusses these issues in detail.

High population growth has two effects. It means that overall

income must grow faster to keep per capita growth

at reasonable levels. To be sure, the fact that population is

growing helps income to grow, because there is a greater

supply of productive labor. However, it is not clear who wins

this seesaw contest: the larger amount of production

or the larger population that makes it necessary to divide that

production among more people. The negative

population effect may well end up dominant, especially if the

economy in question is not endowed with large](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-63-320.jpg)

![and so may not be picked up in the data, the

proportion is probably higher than that revealed by the

published numbers. For the poorest forty-five countries for

which the World Bank publishes data, called the low-income

countries, the average proportion of output from

agriculture is close to 30%. Remember that the poorest forty-

five countries include India and China and therefore a

large fraction of the world’s population. Data for the so-called

middle-income countries, which are the next poorest

sixty-three countries and include most Latin American

economies, is somewhat sketchier, but the percentage

probably averages around 20%. This stands in sharp contrast to

the corresponding income shares accruing to

agriculture in the economically developed countries: around 1–

7%.

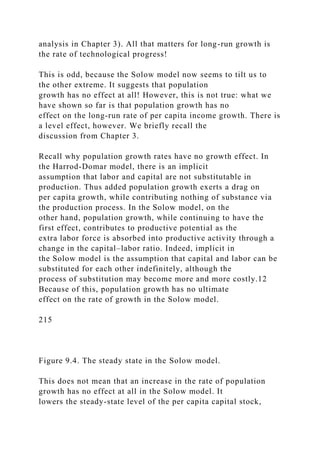

Figure 2.10. Population growth rates and per capita income.

Source: World Development Report (World Bank [1995, 1996]).

Even more striking are the shares of the labor force living in

rural sectors. For the aforementioned low-income

category, the share averaged 72% in 1993 and was as high as

60% for many middle-income countries. The contrast

with developed countries is again apparent, where close to 80%

of the labor force is urbanized. Even then, a large

fraction of this nonurban population is so classified because of

the “commuter effect”: they are really engaged in

nonagricultural activity although they live in areas classified as

rural. Although a similar effect is not absent for

developing countries, the percentage is probably significantly

lower.

Figure 2.11 displays the share of the labor force in agriculture

as we move over different countries indexed by

per capita income. The downward trend is unmistakable, but so

are the huge shares in agriculture for both low- and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-65-320.jpg)

![middle-income countries.

38

Figure 2.11. Fractions of the labor force in agriculture. Source:

World Development Report (World Bank [1996]).

Clearly, agricultural activity forms a significant part of the lives

of people living in developing countries. We

therefore devote a good part of this book to agricultural

arrangements: the hiring of labor, the leasing of land, and

the operation of credit markets. The overall numbers for

production and occupational structure suggest that

agriculture often has lower productivity than other economic

activities. This is not surprising. In many developing

countries, capital intensity in agriculture is at a bare minimum,

and there is often intense pressure on the land. Add

to this the fact that agriculture, especially when not protected

by assured irrigation and ready availability of fertilizer

and pesticides, can be a singularly risky venture. Many farmers

bear enormous risks. These risks may not look very

high if you count them in U.S. dollars, but they often make the

difference between bare-bones subsistence (or

worse) and some modicum of comfort.

2.5.3. Rapid rural–urban migration

With the above-mentioned features, it is hardly surprising that

an enormous amount of labor moves from rural to

urban areas. Such enormous migrations deserve careful study.

They are an outcome of both the “push” from

agriculture, because of extreme poverty and growing

landlessness, and the perceived “pull” of the urban sector. The

pulls are reinforced by a variety of factors, ranging from the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-66-320.jpg)

![to say in Chapter 10. This sector is the home of

last resort—the shelter for the millions of migrants who have

made their way to the cities from the rural sector.

People who shine shoes, petty retailers, and middlemen: they all

get lumped under the broad rubric of services

because there is no other appropriate category. It is fitting that

the World Bank Tables refer to this sector as

“Services, etc.” The large size of this sector in developing

countries is, in the main, a reflection of the inability of

industry in these countries to keep up with the extraordinary

pace of rural–urban migration.

Figure 2.12. Nonagricultural labor in services. Source: World

Development Report (World Bank [1996]).

2.5.4. International trade

By and large, all countries, rich and poor, are significantly

involved in international trade. A quick plot of the

ratio of exports and imports to GNP against per capita income,

does not reveal a significant trend. There are large

countries, such as India, the United States, and Mexico for

which these ratios are not very high—perhaps around

10% on average. Then again, there are countries such as

Singapore and Hong Kong for which these ratios attain

astronomical heights—well over 100%. The modal ratios of

exports and imports to GNP are probably around 20%.

Trade is an important component of the world economy.

Table 2.4. Percentage of the non-agricultural labor force in

services for selected countries.

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-69-320.jpg)

![Source: World Development Report (World Bank [1996]).

The differences between developing and developed countries

are more pronounced when we look at the

composition of trade. Developing countries are often exporters

of primary products. Raw materials, cash crops, and

sometimes food are major export items. Textiles and light

manufactured items also figure on the list. In contrast, the

bulk of exports from developed countries is in the category of

manufactured goods, ranging from capital goods to

consumer durables. Of course, there are many exceptions to

these broad generalizations, but the overall picture is

broadly accurate, as Figure 2.13 shows. This figure plots the

share of exports that comprise primary products

against per capita income. We have followed the now-familar

method of using cross-bars at the mean levels of per

capita income and primary share (unweighted by population) to

eyeball the degree of correlation. It is clear that, on

the whole, developing countries do rely on primary product

exports, whereas the opposite is true for the developed

countries.

Figure 2.13. Share of primary exports in total exports. Source:

World Development Report (World Bank [1995]).

41

Notice that there are some developing countries that have a low

ratio of primary exports. Countries such as

China, India, the Philippines, and Sri Lanka are among them.

These countries and many of their compatriots are

attempting to diversify their exports away from primary

products, for reasons that we indicate subsequently and

discuss at greater length later in the book. At the same time,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-70-320.jpg)

![there are developed countries that export primaries to a

great degree. Australia, New Zealand, and Norway are among

them.

The traditional explanation for the structure of international

trade comes from the theory of comparative

advantage, which states that countries specialize in the export

of commodities in which they have a relative cost

advantage in production. These cost advantages might stem

from differences in technology, domestic consumption

profiles, or the endowment of inputs that are particularly

conducive to the production of certain commodities. We

review this theory in Chapter 16. Because developing countries

have a relative abundance of labor and a relative

abundance of unskilled labor within the labor category, the

theory indeed predicts that such countries will export

commodities that intensively use unskilled labor in production.

To a large extent, we can understand the

aforementioned trade patterns using this theory.

At the same time, the emphasis on primary exports may be

detrimental to the development of these countries for

a variety of reasons. It appears that primary products are

particularly subject to large fluctuations in world prices,

and this creates instability in export earnings. Over the longer

run, as primary products become less important in the

consumption basket of people the world over, a declining price

trend might be evident for such products as well.

Figure 2.14. Changes in the terms of trade, 1980–93. Source:

World Development Report (World Bank [1995] ).

The definite existence of such a trend is open to debate. At the

same time, we can see some broad indication of it

by studying how the terms of trade for different countries have

changed over recent decades. The terms of trade for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-71-320.jpg)

![a country represent a measure of the ratio of the price of its

exports to that of its imports. Thus an increase in the

terms of trade augers well for the trading prospects of that

country, whereas a decline suggests the opposite. Figure

2.14 plots changes in the terms of trade over the period 1980–93

against per capita income. There is some indication

that the relationship is positive, which suggests that poor

countries are more likely than richer ones to face a decline

in their terms of trade. Primary exports may underlie such a

phenomenon.

In general, then, activities that have comparative advantage

today might not be well suited for export earnings

tomorrow. The adjustment to a different mix of exports then

becomes a major concern. Finally, technology often is

assimilated through the act of production. If production and

exports are largely limited to primary products, the

flow of technology to developing countries may be affected. We

discuss these issues in Chapter 17.

42

Figure 2.15. Share of primary imports in total imports. Source:

World Development Report (World Bank [1995]).

The import mix of developing countries is more similar to that

of developed countries. Exporters of primary

products often need to import primary products as well: thus

India might be a major importer of oil and Mexico a

major importer of cereals. Primary exports for each country are

often concentrated in a handful of products, and

there is no contradiction in the fact that primaries are both

exported and imported. A similar argument establishes

that although developed countries might export manufactured](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-72-320.jpg)

![Kuznets): the ratio of incomes earned by the richest 20% of the

population to the those earned by the poorest 40%

of the population. If incomes were distributed almost equally,

what value would you expect this ratio to assume?

What values do you see? In the sample represented by Table

2.1, do you see a trend as we move from poor to rich

countries?

(7) Think of various indicators of development that you would

like to see in your concept of “economic

development.” Think about why per capita income, as measured,

may or may not be a good proxy for these

indicators. Find a copy of the Human Development Report and

look at it to see how different indicators are

combined to get the HDI. Do you think that the method of

combination is reasonable? Can you suggest a better

combination? What do you think of the idea of presenting data

on each of the indicators separately, instead of

combining them? Think of the advantages and disadvantages of

such an approach.

(8) A cogent example in which per capita magnitudes may be

misleading if we do not have a good idea of

distribution comes from the study of modern famine. Why do

famines simply not make sense if we look at them

from the viewpoint of worldwide per capita availability of food

grain? Do they make better sense if we look at just

food-grain availability per capita in that country? After mulling

this over for a while, read the insightful book by

Sen [1981].

(9) (a) Why do you think population growth rates fall with

development? If people consume more goods, in

general, as they get richer and children are just another

consumption good (a source of pleasure to their parents),

then why don’t people in richer countries “consume” more](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-78-320.jpg)

![children?

(b) Why are countries with higher population growth rates

likely to have a greater proportion of individuals below

the age of 15?

(c) Are poorer countries more likely to be rural or is it that rural

countries are more likely to be poor? Which way

does the causality run, or does it run both ways?

(d) Why do you think the international price of sugar might

fluctuate more than, say, that of automobiles?

1 This is not to suggest at all that it is sufficient for every kind

of social advancement.

2 For most poor countries, this starting point was the period

immediately following World War II, when many such

countries, previously

under colonial rule, gained independence and formed national

governments.

3 Even the double emphasis on levels and distribution might not

be enough. For instance, the Human Development Report

(United Nations

Development Programme [1995]) informs us that “the purpose

of development is to enlarge all human choices, not just income.

The concept of

human development is much broader than the conventional

theories of economic development.” More specifically, Sen

[1983] writes:

“Supplementing data on GNP per capita by income

distributional information is quite inadequate to meet the

challenge of development

analysis.” There is much truth in these warnings, which are to

be put side by side with Streeten and certainly contrasted with](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-79-320.jpg)

![Lucas, but I hope

to convince you that an understanding of our “narrower” issues

will take us quite far.

4 For instance, in the case of India, Acharya et al. [1985]

estimated that 18–21% of total income in 1980–81 went

unrecorded in the national

accounts (see also Gupta and Mehta [1981]). For related work

on the “black” or “parallel” economy, see Chopra [1982] and

Gupta and Gupta

[1982].

5 See The Economist, May 15, 1993.

6 In many countries all over the Third World, sectors that are

important or require bulk investment, such as iron and steel,

cement, railways,

and petroleum, are often in the hands of public sector

enterprises.

7 A dollar invested at r% per year will grow to two dollars in T

years, where T solves the equation [l + (r/100)]T = 2. This

means that T

lne[l + (r/100)] = Ine 2. However, Ine 2 is approximately 0.7,

whereas for small values of x, lne(l + x) is approximately x.

Using this in the

equation gets you the result.

8 Of course, our categories are quite coarse and this is not

meant to suggest that there were no relative changes at all

among these countries.

The immobility being described is of a very broad kind, to be

sure.

9 One can imagine that the statistical problems here are even

more severe than those involved in measuring per capita](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-80-320.jpg)

![expressed as a

percentage. The adult literacy index is A ≡ a/100, where a is the

adult literacy rate, expressed as a percentage. Finally, the

income index is Y ≡

(y − 100)/(5,448 − 100), where y is “adjusted income” and

5,448 is the maximum level to which adjusted income is

permitted to climb [see the

Human Development Report (United Nations Development

Programme [1995, p. 134])]. Countries with per capita incomes

of $40,000 (1992

PPP) would be given an adjusted income of this maximum.

14 The emphasis in the quoted sentence (from p. 19 of the

Report) is mine. An earthquake of 8 on the Richter scale is not

“only” 14% more

powerful than one that measures 7 on the Richter scale.

15 For additional information on this debate and related

matters, see the contributions of Anand and Harris [1994],

Aturupane, Glewwe and

Isenman [1994], Desai [1991], Naqvi [1995], Srinivasan [1994],

and Streeten [1994].

16 There are several authors who have argued that higher per-

capita income is correlated with indicators of the quality of life;

see, for

example, Mauro [1993], Pritchett and Summers [1995], Boone

[1996] and Barro [1996]. However, with country fixed effects

properly

accounted for in panel data, the evidence is somewhat mixed:

see Easterly [1997]. Indeed, we do not claim that simple cross-

country studies

can settle the issue conclusively, and we certainly do not

propose that income is a complete determinant for all other

facets of development.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-82-320.jpg)

![of India could take that would lead the Indian economy to grow

like Indonesia’s or Egypt’s? If so, what, exactly? If not, what is

it

about the “nature of India” that makes it so? The consequences

for human welfare involved in questions like these are simply

staggering: Once one starts to think about them, it is hard to

think about anything else.

I quote Lucas at length, because he captures, more keenly than

any other writer, the passion that drives the study

of economic growth. We sense here the big payoff, the

possibility of change with extraordinarily beneficial

consequences, if one only knew the exact combination of

circumstances that drives economic growth.

If only one knew . . . , but to expect that from a single theory

(or even a set of theories) about an incredibly

complicated economic universe would be unwise. As it turns

out, though, theories of economic growth take us quite

far in understanding the development process, at least at some

aggregate level. This is especially so if we

supplement the theories with what we know empirically. At the

very least, it teaches us to ask the right questions in

the more detailed investigations later in this book.

3.2. Modern economic growth: Basic features

Economic growth, as the title of Kuznets’ [1966] pioneering

book on the subject suggests, is a relatively “modern”

phenomenon. Today, we greet 2% annual rates of per capita

growth with approval but no great surprise. Remember,

however, that throughout most of human history, appreciable

growth in per capita gross domestic product (GDP)

was the exception rather than the rule. In fact it is not far from

the truth to say that modern economic growth was

born after the Industrial Revolution in Britain.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-84-320.jpg)

![numbers are stunning. On average (see the last row of

the table), GDP per capita in 1913 was 1.8 times the figure for

1870; by 1978, this ratio climbed to 6.7! A nearly

sevenfold increase in real per capita GDP in the space of a

century cannot but transform societies completely. The

developing world, which is currently going through its own

transformation, will be no exception.

Table 3.1. Per capita GDP in selected OECD countries, 1870–

1978.

Source: Maddison [1979].

Indeed, in the broader sweep of historical time, the development

story has only just begun. The sustained growth

in the last century was not experienced the world over. In the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries, only a handful of

countries, mostly in Western Europe and North America, and

largely represented by the list in Table 3.1, could

manage the “takeoff into sustained growth,’ to use a well-known

term coined by the economic historian W. W.

Rostow. Throughout most of what is commonly known as the

Third World, the growth experience only began well

into this century; for many of them, probably not until the post-

World War II era, when colonialism ended.

Although detailed and reliable national income statistics for

most of these countries were not available until only a

few decades ago, the economically backward and stagnant

nature of these countries is amply revealed in less

quantitative historical accounts, and also by the fact that they

are way behind the industrialized nations of the world

today in per capita GDP levels. To see this, refer to Table 3.2.

What this table does is record the per capita incomes

of several developing countries relative to that of the United

States, for 1987–94. It also records the movements of

per capita income in these countries relative to the United](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-86-320.jpg)

![States over the same period.

Table 3.2. Per capita GDP in Selected Developing Countries

Relative to that of the United States, 1987–94.

48

Source: World Bank Development Report [1996].

There is, then, plenty of catching-up to do. Moreover, there is a

twist in the story that wasn’t present a century

ago. Then, the now-developed countries grew (although

certainly not in perfect unison) in an environment

uninhabited by nations of far greater economic strength. Today,

the story is completely different. The developing

nations not only need to grow, they must grow at rates that far

exceed historical experience. The developed world

already exists, and their access to economic resources is not

only far higher than that of the developing countries,

but the power afforded by this access is on display. The urgency

of the situation is further heightened by the

extraordinary flow of information in the world today. People are

increasingly and more quickly aware of new

products elsewhere and of changes and disparities in standards

of living the world over. Exponential growth at rates

of 2% may well have significant long-run effects, but they

cannot match the parallel growth of human aspirations,

and the increased perception of global inequalities. Perhaps no

one country, or group of countries, can be blamed

for the emergence of these inequalities, but they do exist, and

the need for sustained growth is all the more urgent as

a result.

3.3. Theories of economic growth](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-87-320.jpg)

![to produce a single unit of output in the economy, and it is

represented by the ratio K(t)/Y(t).

Combining (3.3) and (3.4), using these new concepts, and

moving terms around a bit (see the Appendix to this

chapter for the easy details), we arrive at a very influential

equation indeed:

where g is the overall rate of growth that is defined by the value

[Y(t 1) − Y(t)]/Y(t). This is the Harrod–Domar

equation, named after Roy Harrod and Evsey Domar, who wrote

well-known papers on the subject in 1939 and

1946, respectively.

It isn’t difficult to see why the Harrod–Domar equation was

influential. It has the air of a recipe. It firmly links

the growth rate of the economy to two fundamental variables:

the ability of the economy to save and the capital–

output ratio. By pushing up the rate of savings, it would be

possible to accelerate the rate of growth. Likewise, by

increasing the rate at which capital produces output (a lower θ),

growth would be enhanced. Central planning in

countries such as India and the erstwhile Soviet Union was

deeply influenced by the Harrod–Domar equation (see

boxes).

A small amendment to the Harrod–Domar model allows us to

incorporate the effects of population growth. It

should be clear that as the equation currently stands, it is a

statement regarding the rate of growth of total gross

national product (GNP), not GNP per capita. To talk about per

capita growth, we must net out the effects of

population growth. This is easy enough to do. If population (P)

grows at rate n, so that P(t + 1) = P(t)(1 + n) for all

t, we can convert our equations into per capita magnitudes. (The

chapter appendix records the simple algebra](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-94-320.jpg)

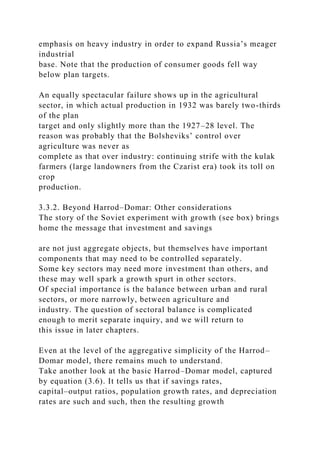

![Table 3.3. Targets and achievements of the first Soviet five

Year Plan (1928–29 to 1932–33).a

Source: Dobb [1966].

aAll figures are in 100 million 1926–27 rubles.

Toward the end of the 1920s, the need for a coordinated

approach to tackle the problem of industrialization on all fronts

was strongly

felt. Under the auspices of the State Economic Planning

Commission (called the Gosplan), a series of draft plans was

drawn up which

culminated in the first Soviet Five Year Plan (a predecessor to

many more), which covered the period from 1929 to 1933. At

the level of

objectives, the plan placed a strong emphasis on industrial

growth. The resulting need to step up the rate of investment was

reflected in the

plan target of increasing it from the existing level of 19.9% of

national income in 1927–28 to 33.6% by 1932–33. (Dobb [1966,

p. 236]).

How did the Soviet economy perform under the first Five Year

Plan? Table 3.3 shows some of the plan targets and actual

achievements, and what emerges is quite impressive. Within a

space of five years, real national income nearly doubled,

although it stayed

slightly below the plan target. Progress on the industrial front

was truly spectacular: gross industrial production increased

almost 2.5 times.

This was mainly due to rapid expansion in the machine

producing sector (where the increment was a factor of nearly 4,

far in excess of

even plan targets), which is understandable, given the enormous](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-97-320.jpg)

![this in the theory. We told a similar story with population

growth rates, which are just as capable of being

endogenous.

More important than the mere recognition of endogeneity is the

understanding that such features may

fundamentally alter the way we think about the economy and

about policy. We saw how this might happen in the

case of endogenous population growth, but the most startling

and influential example of all is the model that we

turn to now. Developed by Solow [1956], this model has had a

major impact on the way economists think about

economic growth. It relies on the possible endogeneity of yet

another parameter in the Harrod–Domar model: the

capital–output ratio.

3.3.3. The Solow model

Introduction

Solow’s twist on the Harrod–Domar story is based on the law of

diminishing returns to individual factors of

production. Capital and labor work together to produce output.

If there is plenty of labor relative to capital, a little

56

bit of capital will go a long way. Conversely, if there is a

shortage of labor, capital-intensive methods are used at

the margin and the incremental capital–output ratio rises. This

is exactly in line with our previous discussion:

according to the Solow thesis, the capital–output ratio θ is

endogenous. In particular, θ might depend on the

economywide relative endowments of capital and labor.8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-107-320.jpg)

![The Solow equations

To understand the implications of this modification, it will help

to go through a set of derivations very similar to

those we used for the Harrod–Domar model. We may retain

equations (3.3) (savings equal investment) and (3.4)

(capital accumulation) without any difficulty. Retaining, too,

the assumption that total savings S(t) is a constant

fraction s of total income Y(t), we may combine (3.3) and (3.4)

to get

If we divide through by population (Pt) and assume that

population grows at a constant rate, so that P(t + 1) = (1 +

n)Pt, (3.8) changes to

where the lowercase ks and ys represent per capita magnitudes

(K/P and Y/P, respectively).

Before going on, make sure you understand the economic

intuition underlying the algebra of (3.9). It is really

ery si le. he right hand side has two arts, de reciated er ca ita ca

ital which is (1 − δ)k(t)] and current per

capita savings [which is sy(t)]. Added together, this should give

us the new per capita capital stock k(t + 1), except

for one complication: population is growing, which exerts a

downward drag on per capita capital stocks. This is

why the left-hand side of (3.9) has the rate of growth of

population (n) in it. Note that the larger the rate of

population growth, the lower is per capita capital stock in the

next period.

To complete our understanding of the Solow model, we must

relate per capita output at each date to the per

capita capital stock, using the production function. The

production function, as you know, represents the technical

knowledge of the economy. In this model, capital and labor

work together to produce total output. With constant](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-108-320.jpg)

![this way, the Solow model is a pointer to studying the

economics of technological progress, arguing that it is there

that one must look for the ultimate sources of growth. This is

not to say that such a claim is necessarily true, but it

is certainly provocative and very far from being obviously

wrong.

Second, the method of reasoning used in the basic Solow model

can be adapted easily to include technical

progress of this kind. Let’s take a few moments to go through

the adaptation, because the arguments are important

to our understanding of the theory of growth.

A simple way to understand technical progress is to envision

that such progress contributes to the efficiency, or

economic productivity, of labor. Indeed, as we will see later, it

is not only increased technical know-how, but other

advances (such as increased and better education) that

contribute to enhanced labor productivity. Thus although we

concentrate here on technical progress, our approach applies

equally to the increased productivity brought about by

higher education, and not necessarily newer technology.

Let’s begin by returning to equation (3.8), which describes the

accumulation of capital and remains perfectly

valid with or without technical progress. Now let’s make a

distinction between the working population P(t) and the

amount of labor in “efficiency units” [call it L(t)] used in

production—the effective population, if you like. This

61

distinction is necessary because in the extension of the model

that we now consider, the productivity of the working](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-118-320.jpg)

![the initial value of per capita income.

It is quite clear from our discussion that the hypothesis of

unconditional convergence takes us out on a limb. Not

only does it require the convergence of countries to their own

steady states, but it asserts that these steady states are

all the same! Let us see what the data have to say on this matter.

3.5.3. Unconditional convergence: Evidence or lack thereof

The first problem that arises when testing a hypothesis of this

sort is the issue of time horizons. The systematic

collection of data in the developing economies started only

recently, and it is hard to find examples of reliable data

that stretch back a century or more. There are, then, two

choices: cover a small number of countries over a large

period of time or cover a large number of countries over a short

period of time. We will look at examples of both

approaches.

A small set of countries over a long time horizon

Baumol [1986] examined the growth rates of sixteen countries

that are among the richest in the world today.

Thanks to the work of Maddison [1982, 1991], data on per

capita income are available for these countries for the

year 1870. Baumol’s idea was simple but powerful: plot 1870

per capita income for these sixteen countries on the

horizontal axis and plot the growth rate of per capita income

over the period 1870–1979 (measured by the difference

in the logs of per capita income over this time period) on the

vertical axis. Now examine whether the relationship

between the various observations fits the level convergence

hypothesis. As we discussed in the previous section, if

the hypothesis is correct, the observations should approximately

lie on a downward-sloping line.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-123-320.jpg)

![Indeed, the exercise seems to pay off very well. Although the

countries in Maddison’s data set had comparable

per capita incomes in 1979, they had widely different levels of

per capita income in 1870. It appears, then, that

Baumol’s finding supports the unconditional convergence

hypothesis quite strongly.12 Figure 3.8, which is taken

from De Long [1988], carries out this exercise by plotting the

countries with the log of 1870 income on one axis

and their subsequent growth on the other. The countries, read

from poorest to richest in 1870, are Japan, Finland,

Sweden, Norway, Germany, Italy, Austria, France, Canada,

Denmark, the United States, the Netherlands,

Switzerland, Belgium, the United Kingdom, and Australia. The

figure shows the strong negative relationship in

Baumol’s study that is characteristic of unconditional

convergence.

Unfortunately, Baumol’s study provides a classic case of a

statistical pitfall. He only considered countries that

are rich ex post; that is, they had similar per capita GDP levels

in 1979. In 1870, with no knowledge of the future,

what criteria would tell us to choose these countries ex ante to

test convergence down the road? A good illustration

of the statistical error is the inclusion of Japan in the sample. It

is there precisely because of hindsight: Japan is rich

today, but in 1870, it was probably midway in the world’s

hierarchy of nations arranged by per capita income. If

Japan, why not Argentina or Chile or Portugal?13

Thus, it may be alleged that the “convergence” that Baumol

found is a result only of a statistical regularity

rather than any underlying tendency of convergence.14 A true

test of convergence would have to look at a set of

countries that, ex ante, seemed likely to converge to the high

per capita GDP levels that came to characterize the

richest nations several decades later.15 It would not be fair to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-124-320.jpg)

![countries studied by De Long. New countries are shown as

squares; original

countries as diamonds. Source: De Long [1988].

Figure 3.9 shows the modified pictures after De Long’s

countries are added and Japan is dropped from the initial

sixteen. The earlier observations from Figure 3.8 appear as

unlabeled dots. Now matters don’t look so good for

convergence, and indeed, De Long’s statistical analysis

confirms this gloomier story. Baumol’s original regression

can now be repeated on this new data set: regress the log

difference in per capita income between 1870 and 1979 on

the logarithm of 1870 per capita income and a constant.17 The

slope coefficient of the regression is still appreciably

65

negative, but the “goodness-of-fit” is very bad, as indicated by

the fact that the residual disturbance term is very

large.

De Long also argued, and correctly so, that the 1870 data are

likely to contain large measurement errors (relative

to those in 1979), which make the various observations more

scattered than they actually should be and makes any

measurement of convergence more inflated than the case

actually merits.18 De Long repeated his regression

exercise, assuming a stipulated degree of measurement error in

the 1870 data and making necessary amendments to

his estimation technique to allow for this, and found that the

slope coefficient comes out to be very close to zero—

indicating that there is very little systematic relationship

between a country’s growth rate and its per capita GDP, at

least in the cross section of the twenty-two countries studied.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-126-320.jpg)

![A large set of countries over a short time horizon

The second option is to include a very large set of countries to

test for unconditional convergence. This approach

has the advantage of “smoothing out” possible statistical

irregularities in looking at a small sample. The

disadvantage is that the time span of analysis must be shortened

to a few decades, which is the span over which

reliable data are available for a larger group of countries.

In Chapter 2, we used the Summers–Heston data set to say

something about the world distribution of income

over the period 1965–85. If you turn back to that chapter and

reread the discussion there, it should be clear that

unconditional convergence sounds like a pretty long shot. At the

very least, the gap between the richest and the

poorest countries does not seem to have appreciably narrowed.

With per capita GDP expressed as a fraction of the

U.S. level in the same year, a plot of the average for the five

richest and the five poorest nations over a twenty-six

year period (1960–85) displays a more or less constant relative

gap between them. This is not to say that the poorest

countries have not moved up in absolute terms: the average per

capita income of the poor countries [expressed as a

fraction of a fixed level (1985) of U.S. per capita GDP, as

opposed to contemporaneous U.S. levels] shows a clear

upward trend over the period. Nevertheless, the disparity in

relative incomes (let alone that in absolute incomes) has

stayed the same, because the poorest countries have grown at

more or less the same rate as the richest.

An objection at this point is that a good sample should be broad

based; that is, focused not merely on the richest

and the poorest in the sample. Indeed, we were careful to do

this in Chapter 2 as well, where we noted how diverse

the experiences of different countries have been over this](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-127-320.jpg)

![period. We noted, moreover, that if we group countries

into different clusters and then construct a mobility matrix to

track their movements from one cluster to another,

there is little tendency for countries to move toward a common

cluster.

A similar tendency is noted from a different kind of statistical

analysis. Parente and Prescott [1993] studied 102

countries over the period 1960–85. In this study, each country’s

per capita real GDP is expressed in relative terms:

as a fraction of U.S. per capita GDP for the same year. The

authors then calculated the standard deviation19 of these

values separately for each year. Whereas the convergence

hypothesis says that countries move closer to each other

in income levels, we expect the standard deviation of their

relative incomes to fall over time. In Parente and

Prescott’s study, however, it actually increased by 18.5% over

the twenty-six year period, and the increase was

fairly uniform from year to year. However, there is some

variation here if we look at geographical subgroupings.

The standard deviation in relative incomes for Western

European countries shows a clear decline. In fact this

decline persists through the period 1913–85. On the other hand,

the same measure applied to Asian countries

displays a significant and pronounced increase, and the

divergence in this region is consistent with data going all

the way back to 1900.

To put the data together in yet another way, suppose that we

regress average per capita growth between 1960

and 1985 on per capita GDP in 1960. Just as in the Baumol

study, the tendency toward level convergence would

show up in a negative relationship between these two

variables,20 but, in line with the discussion in the rest of this

section, there is no clear tendency at all. Barro [1991] observed

that the correlation between these two variables is](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-128-320.jpg)

![Therefore we enter the empirical study with the following

expectations:

(1) The coefficients on the term Ins are positive and the

coefficient on the term ln(n + π ) is negati e. his

captures the Solow prediction that savings has a positive (level)

effect on per capita income and population growth

has a negative (level) effect on per capita income.

(2) The estimated coefficients have the same approximate

magnitude, and this magnitude is around 0.5.

Mankiw, Romer, and Weil [1992] tested these predictions using

the Heston–Summers data set. They took π

to be approximately 0.05, or around 5% per year, and used the

average of investment–GDP ratios over the period

1965–85 to form an estimate of the savings rate. The variable y

is given by per capita GDP in the year 1985. The

resulting regression shows the following features:

(1) More than half the worldwide variation in per capita GDP in

1985 can be explained by the two variables s

and n. The correlation coefficient of the regression is 0.59. This

is a powerful finding indeed.

(2) As predicted by the Solow model, the coefficient of In s is

significant and positive, whereas that of ln(n + π

) is signi icant and negati e. n ualitati e ter s, as long as we do

not stic to the absurd assu tion o e ual

savings and population growth rates (and therefore the

prediction of unconditional convergence), the Solow model

predicts broad relationships that do show up in worldwide data.

However, there is a bug:](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1developmenteconomics-221224051007-11cbd63c/85/1Development-Economics-docx-136-320.jpg)

![distinction is

between the flows of current and future consumption, and many

goods embody a little of each.

4 We assume that the economy is closed—that there are no net

flows of resources from or to the outside world. Moreover, we

ignore