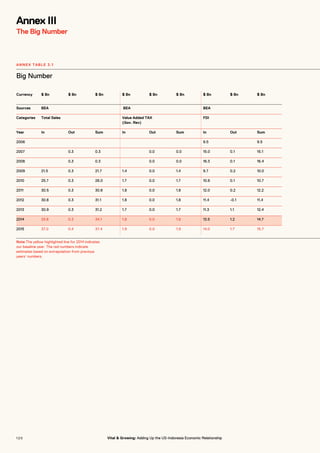

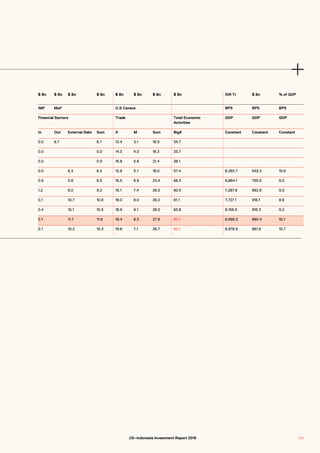

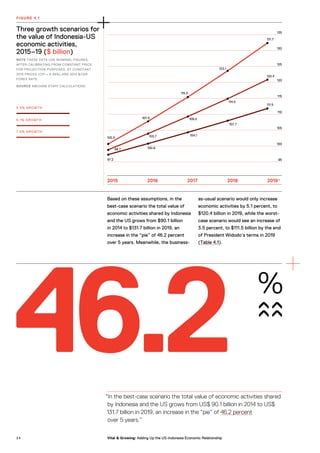

The report summarizes the total economic relationship between the US and Indonesia in 2014 as $90.1 billion ("the Big Number"). This figure represents 10.1% of Indonesia's GDP that year and has grown at an average annual rate of 8% from 2010-2015, outpacing Indonesia's GDP growth of 5.5% over the same period. The Big Number includes five components: domestic sales ($34.1B), bilateral trade ($27.6B), FDI ($14.7B), finance ($11.8B), and government revenue ($1.8B). Domestic sales make up the largest share, followed by trade, FDI, finance, and revenue.

![play on the minds of legislators there

is an increasing likelihood that the

passage of the draft law will be delayed.

Finally, there is the concern shared

by many foreign investors across

the country that the ability to

bring in foreign talent is becoming

increasingly difficult. US companies

in general employ a far higher share

of Indonesians than foreign workers,

with our 2016 survey of US companies

showing that US companies employ on

average about 1,160 Indonesia workers

for every expat employee. However,

there is often a limited availability of

locally sourced skills and technical

capacity. It is therefore crucially

important that companies are allowed

to bring in foreign talent according to

their own needs, not only to maximize

production but also to help transfer

knowledge, expertise and experience

to local employees. Restrictions on the

employment of foreign workers, and

the ease with which they can come and

go depending on work requirements,

also make it very hard for potential

investors to consider making

Indonesian a regional hub or ASEAN

headquarters. While some of the more

impractical suggestions such as forcing

all foreign workers to become fluent in

Indonesian have been quietly shelved,

the issue remains of considerable

concern, and appears to fly in the face

of President Joko Widodo’s appeals for

greater foreign investment in Indonesia.

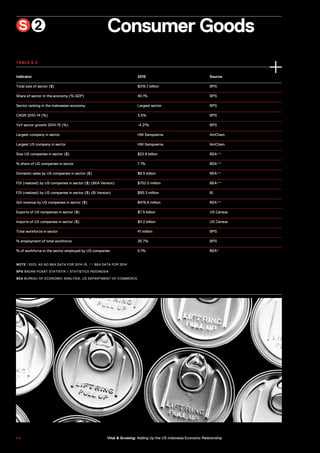

The Role of US Companies in

the Sector

As the largest sector in the economy,

the consumer goods sector also sees

the largest total economic activities by

US companies across all nine sectors

in our analysis, at $22.6 billion, or 7.1

percent of the total. The sector has

remained robust despite the economic

slowdown, posting a CAGR of 3.5

percent in 2010-14. However, the

year-on-year growth seen in 2014-

15 was -4.2 percent, confirming that

2015 was a tough year. Noteworthy

US companies operating in this sector

include 3M, ACE Hardware, Amway,

Coca Cola, General Motors, Goodyear,

HM Sampoerna, Levi Strauss, Mattel,

Procter and Gamble (P&G), UL

(Underwriter Laboratories), and food

outlets such as Starbucks, Burger King,

KFC, McDonalds, Pizza Hut

and Wendy’s.

Our 2016 survey of US

companies show[s] that

US companies employ

on average about 1,160

Indonesia workers for

every expat employee.

7 0 Vital & Growing: Adding Up the US-Indonesia Economic Relationship](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/06303e24-65e6-4806-8c88-e70580f6f330-170130104037/85/16-09-14-AmchamInvestmentReport-FULL-72-320.jpg)