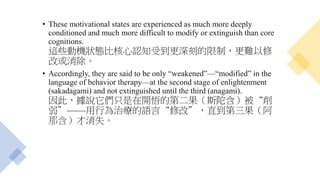

This document discusses concepts from Buddhism and spiritual practice. It provides guidance on cultivating loving-kindness by focusing on a friend's happiness. It then discusses the importance of developing a healthy sense of self before practicing non-self. Later sections explore gradual vs sudden spiritual change, and how enlightenment may clarify imperfections but not instantly remove them, requiring continued practice.

![• Andrew Cohen (2000) asked me whether I didn’t agree that if one’s

enlightenment is deep enough,

Andrew Cohen (2000年) 問我是否不同意如果一個人的

[覺悟] 足夠深,

• the fixation on the personal self and all the suffering associated with it

will disappear because one’s perspective will shift completely,

對個人[自我]的執著以及與之相關的所有痛苦都會消失,

因為一個人的觀點將完全轉變,

• from seeing oneself as the one who was wounded to recognizing

oneself as that which was never wounded by anything.

從將自己視為受傷者,到意識到自己從未被任何事物傷

害過。

• Won’t realization of the emptiness and ultimate insubstantiality of the

personal self and its suffering completely change one’s relationship to

personal experience?

問題:認識個人 (自我) 的 [空性] 和最終的非實質及其痛

苦,難道不會徹底改變一個人與個人經驗的關係嗎?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12202023-231220181227-4974c2a9/85/12-20-2023-8-320.jpg)

![• Pleasurable experience will not produce attraction and clinging.

愉快的體驗不會產生吸引力和執著。

• Pain will simply remain pain, pleasure simply remain pleasure,

痛依然是痛,樂依然是樂,

• without the reactive approach-avoidance response that much of

psychoanalytic affect theory,

沒有大部分[精神分析影響理論]中的反應性接近-迴避反

應,

• by contrast, tends to consider innate and views as leading to the

constellation of enduring drive or motivational states.

相較之下,傾向於認為先天和觀點會導致持久的動力或

動機狀態。](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/12202023-231220181227-4974c2a9/85/12-20-2023-11-320.jpg)