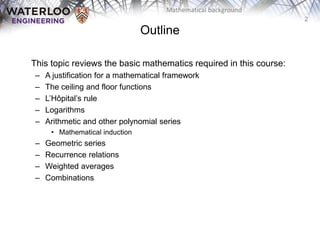

This document provides an overview of various mathematical topics required for an algorithms and data structures course, including:

- Justification for using quantitative methods like mathematics to evaluate algorithms and data structures.

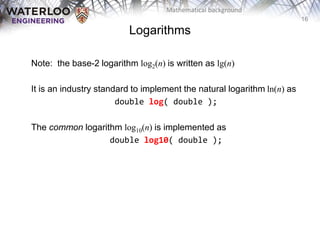

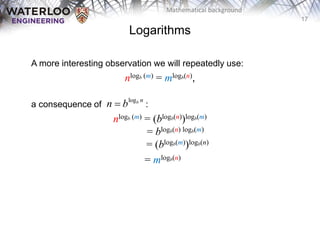

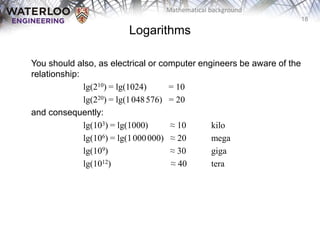

- Common functions like floor, ceiling, and logarithms.

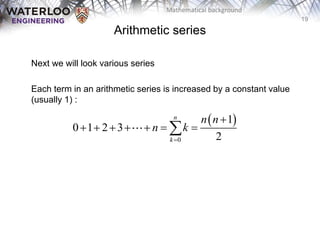

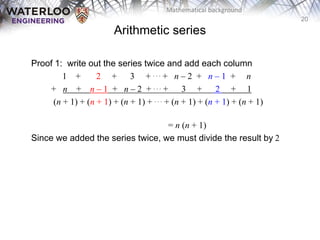

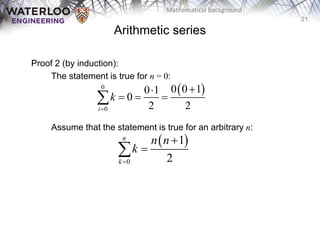

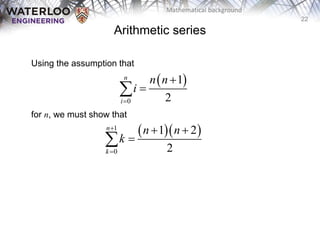

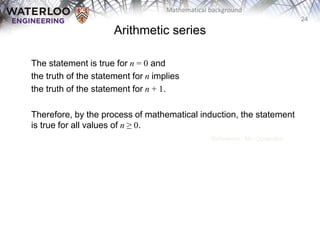

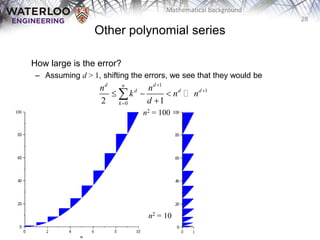

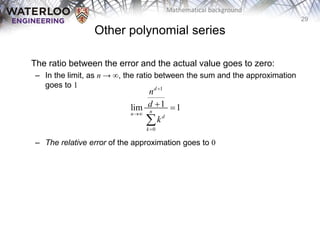

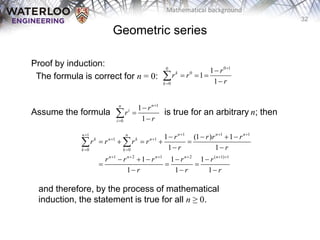

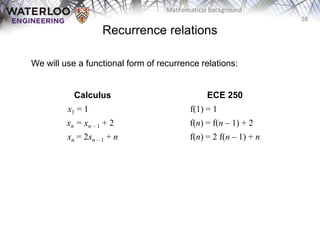

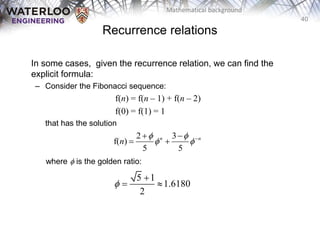

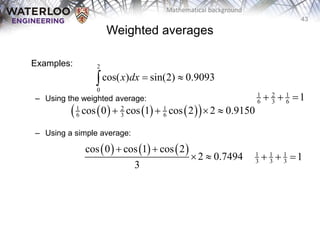

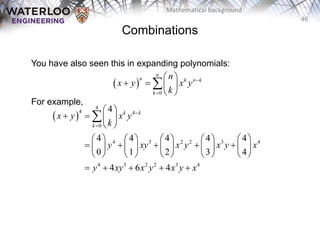

- Properties and proofs of arithmetic series, geometric series, and other polynomial series.

- Introduction of concepts like mathematical induction that will be used throughout the course.

![49

Mathematical background

[1] Cormen, Leiserson, and Rivest, Introduction to Algorithms,

McGraw Hill, 1990, Chs 2-3, p.42-76.

[2] Weiss, Data Structures and Algorithm Analysis in C++, 3rd Ed.,

Addison Wesley, §§ 1.2-3, p.2-11.

Reference](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1-230529061316-7bb89aff/85/1-02-Mathematical_background-pptx-49-320.jpg)