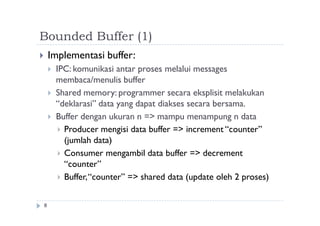

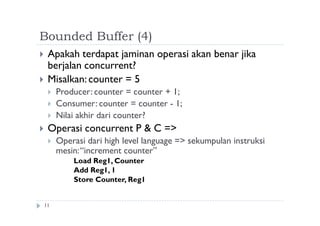

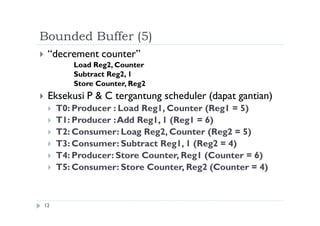

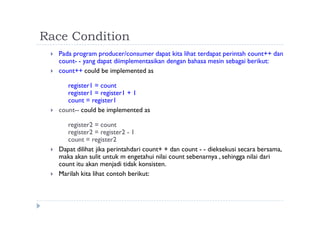

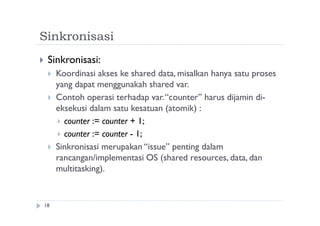

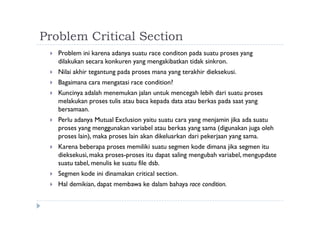

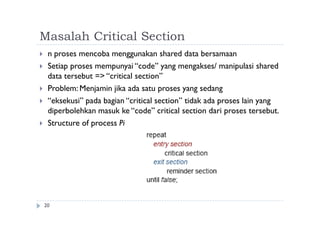

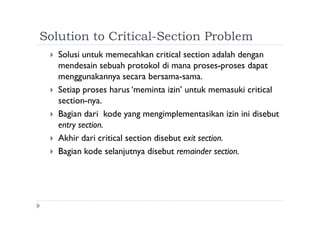

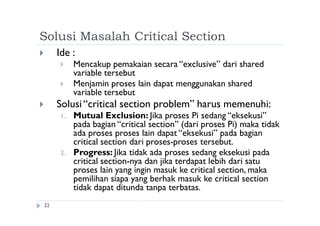

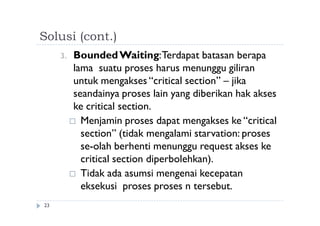

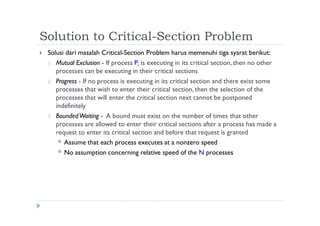

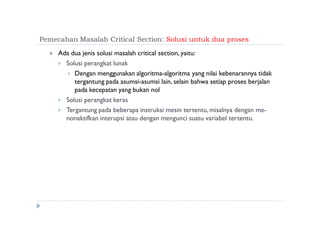

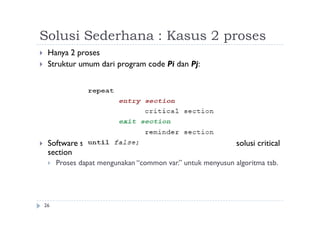

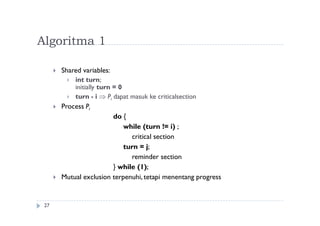

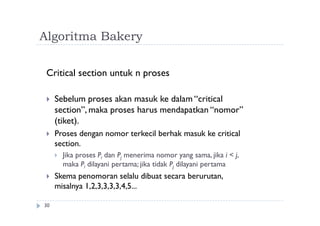

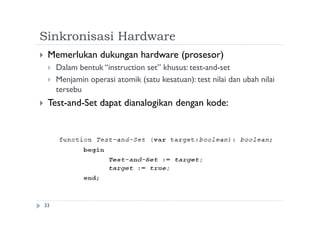

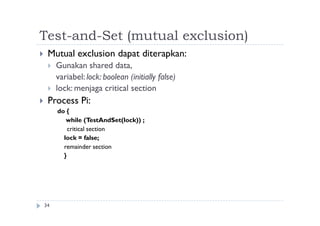

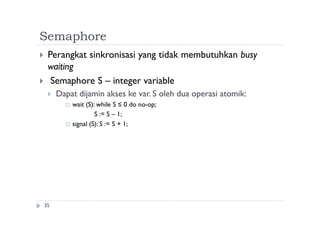

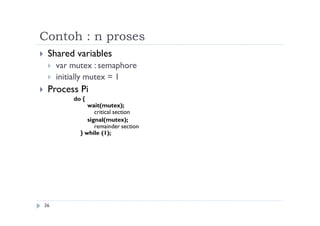

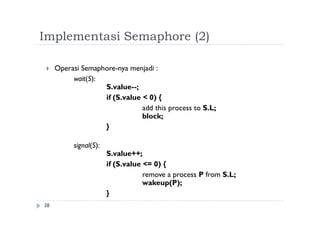

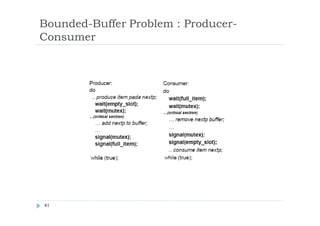

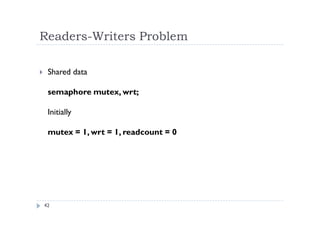

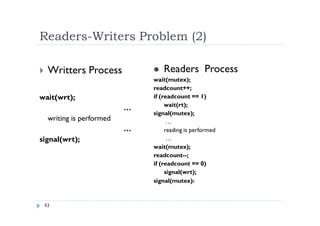

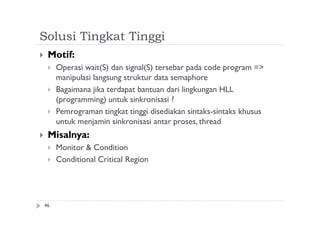

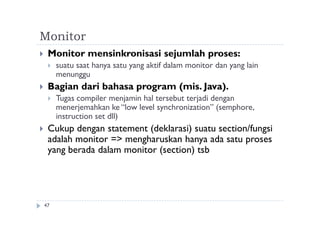

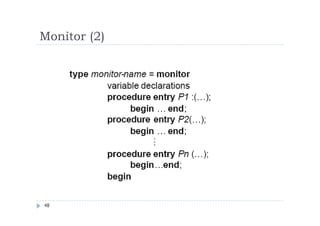

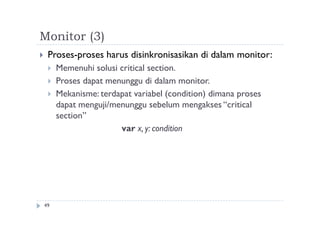

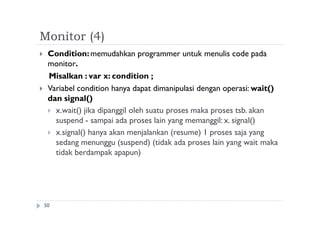

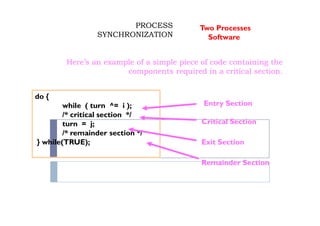

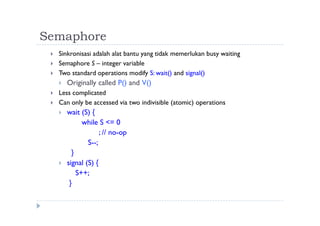

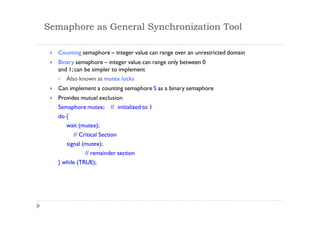

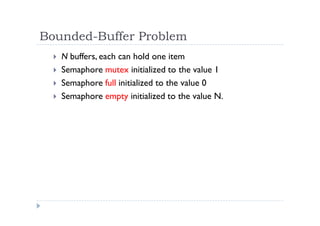

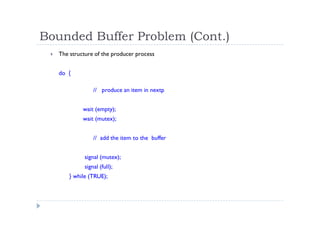

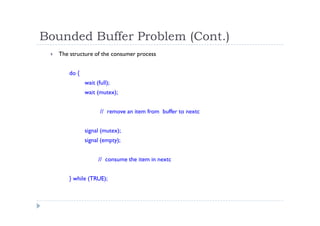

The document discusses synchronization of processes and solutions to critical section problems. It covers background on concurrency and shared data leading to inconsistent states. The bounded buffer problem is presented as an example requiring synchronization. Race conditions can occur when multiple processes concurrently update shared data. Solutions must ensure mutual exclusion and progress. Peterson's algorithm and semaphores are introduced as synchronization techniques.

![Bounded Buffer (2)

9

Shared data type item = … ;

var buffer array

in, out: 0..n-1;

counter: 0..n;

in, out, counter := 0;

Producer process

repeat

…

produce an item in nextp

…

while counter = n do no-op;

buffer [in] := nextp;

in := in + 1 mod n;

counter := counter +1;

until false;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-9-320.jpg)

![Bounded Buffer (3)

10

Consumer process

repeat

while counter = 0 do no-op;

nextc := buffer [out];

out := out + 1 mod n;

counter := counter – 1;

…

consume the item in nextc

…

until false;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-10-320.jpg)

![Producer

while (true) {

/* produce an item and put in nextProduced

*/

while (count == BUFFER_SIZE)

; // do nothing

buffer [in] = nextProduced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count++;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-13-320.jpg)

![Consumer

while (true) {

while (count == 0)

; // do nothing

nextConsumed = buffer[out];

out = (out + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

count--;

/* consume the item in nextConsumed

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-14-320.jpg)

![Algoritma 2

28

Shared variables

boolean flag[2];

initially flag [0] = flag [1] = false.

flag [i] = true Pi siap dimasukkan ke dalam critical section

Process Pi

do {

flag[i] := true;

while (flag[j]) ;

critical section

flag [i] = false;

remainder section

} while (1);

Mutual exclusion terpenuhi tetapi progress belum terpenuhi.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-28-320.jpg)

![Algoritma 3

29

Kombinasi shared variables dari algoritma 1 and 2.

Process Pi

do {

flag [i]:= true;

turn = j;

while (flag [j] and turn = j) ;

critical section

flag [i] = false;

remainder section

} while (1);

Ketiga kebutuhan terpenuhi, solusi masalah critical section

pada dua proses](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-29-320.jpg)

![Algoritma Bakery (2)

31

Notasi < urutan lexicographical (ticket #, process id #)

(a,b) < c,d) jika a < c atau jika a = c and b < d

max (a0,…, an-1) dimana a adalah nomor, k, seperti pada k

ai untuk i - 0,

…, n – 1

Shared data

var choosing: array [0..n – 1] of boolean

number: array [0..n – 1] of integer,

Initialized: choosing =: false ; number => 0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-31-320.jpg)

![Algoritma Bakery (3)

32

do {

choosing[i] = true;

number[i] = max(number[0],number[1], …, number [n –

1])+1;

choosing[i] = false;

for (j = 0; j < n; j++) {

while (choosing[j]) ;

while ((number[j] != 0) && (number[j,j] <

number[i,i])) ;

}

critical section

number[i] = 0;

remainder section

} while (1);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-32-320.jpg)

![Dining-Philosophers Problem

44

Shared data

semaphore chopstick[5];

Semua inisialisasi bernilai 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-44-320.jpg)

![Dining-Philosophers Problem

45

Philosopher i:

do {

wait(chopstick[i])

wait(chopstick[(i+1) % 5])

…

eat

…

signal(chopstick[i]);

signal(chopstick[(i+1) % 5]);

…

think

…

} while (1);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-45-320.jpg)

![Pemecahan Masalah Critical Section: Peterson’s

Solution

Two process solution

Assume that the LOAD and STORE instructions are atomic; that is,

cannot be interrupted.

The two processes share two variables:

int turn;

Boolean flag[2]

The variable turn indicates whose turn it is to enter the critical

section.

The flag array is used to indicate if a process is ready to enter the

critical section. flag[i] = true implies that process Pi is ready!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-52-320.jpg)

![Algorithm for Process Pi

do {

flag[i] = TRUE;

turn = j;

while (flag[j] && turn == j);

critical section

flag[i] = FALSE;

remainder section

} while (TRUE);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-54-320.jpg)

![Bounded-waiting Mutual Exclusion with TestandSet()

do {

waiting[i] = TRUE;

key = TRUE;

while (waiting[i] && key)

key = TestAndSet(&lock);

waiting[i] = FALSE;

// critical section

j = (i + 1) % n;

while ((j != i) && !waiting[j])

j = (j + 1) % n;

if (j == i)

lock = FALSE;

else

waiting[j] = FALSE;

// remainder section

} while (TRUE);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-61-320.jpg)

![Dining-Philosophers Problem

Shared data

Bowl of rice (data set)

Semaphore chopstick [5] initialized to 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-75-320.jpg)

![Dining-Philosophers Problem (Cont.)

The structure of Philosopher i:

do {

wait ( chopstick[i] );

wait ( chopStick[ (i + 1) % 5] );

// eat

signal ( chopstick[i] );

signal (chopstick[ (i + 1) % 5] );

// think

} while (TRUE);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-76-320.jpg)

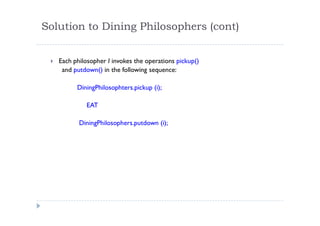

![Solution to Dining Philosophers

monitor DP

{

enum { THINKING;HUNGRY, EATING) state [5] ;

condition self [5];

void pickup (int i) {

state[i] = HUNGRY;

test(i);

if (state[i] != EATING) self [i].wait;

}

void putdown (int i) {

state[i] = THINKING;

// test left and right neighbors

test((i + 4) % 5);

test((i + 1) % 5);

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-82-320.jpg)

![Solution to Dining Philosophers (cont)

void test (int i) {

if ( (state[(i + 4) % 5] != EATING) &&

(state[i] == HUNGRY) &&

(state[(i + 1) % 5] != EATING) ) {

state[i] = EATING ;

self[i].signal () ;

}

}

initialization_code() {

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++)

state[i] = THINKING;

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fkqdtiblrqu4yulc7cv5-140524215617-phpapp02/85/09-sinkronisasi-proses-83-320.jpg)