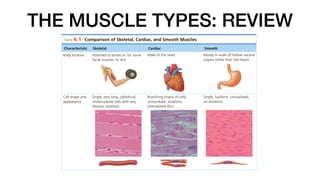

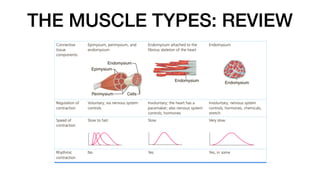

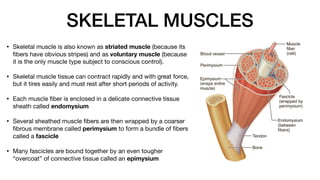

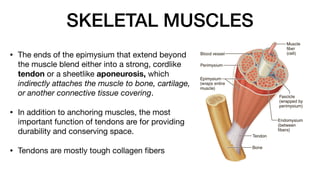

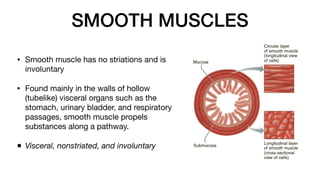

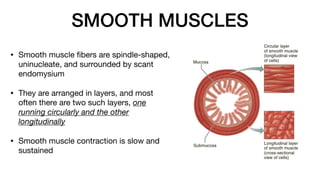

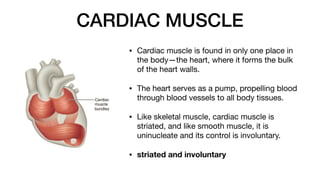

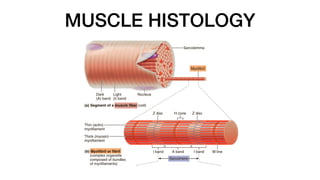

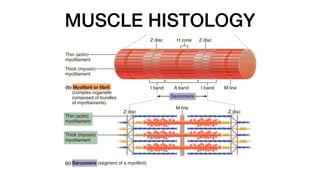

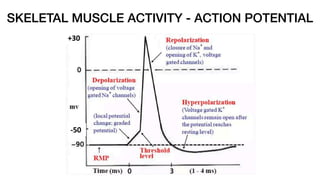

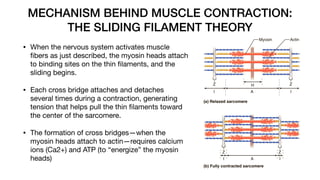

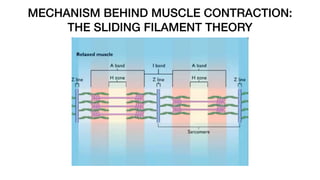

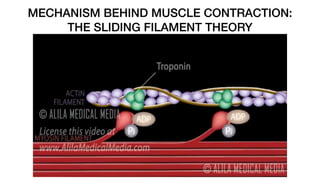

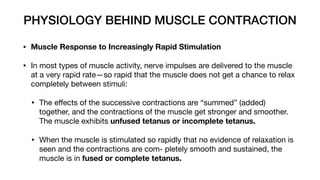

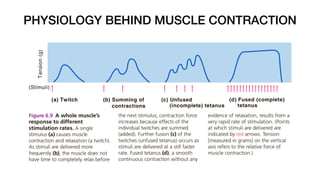

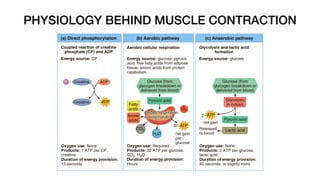

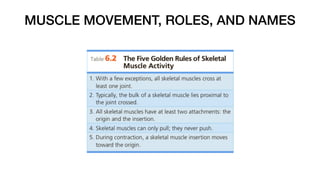

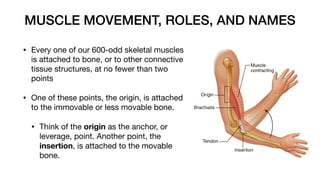

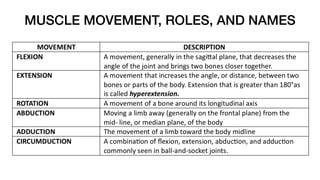

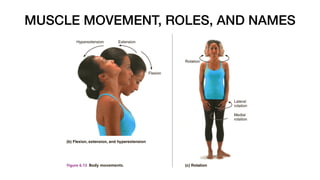

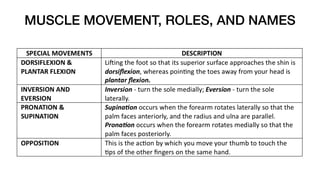

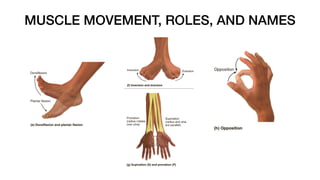

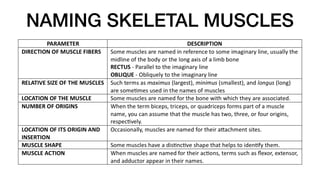

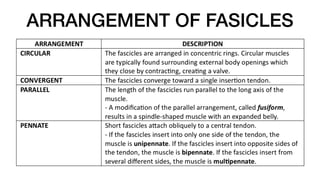

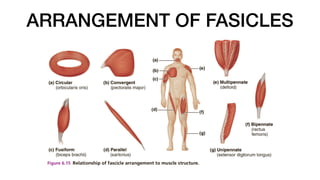

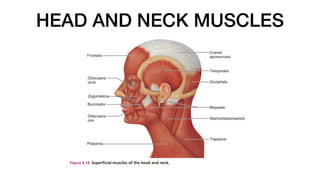

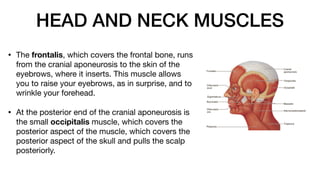

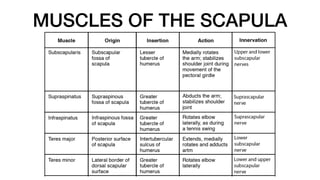

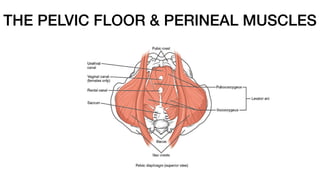

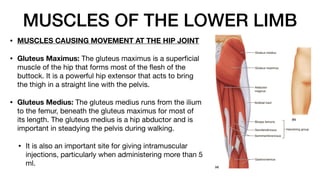

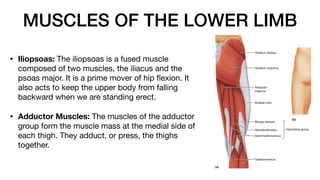

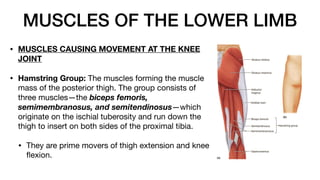

The document outlines the muscular system, detailing the three muscle types: skeletal, smooth, and cardiac muscles, highlighting their structures, functions, and physiological properties. It explains muscle contraction mechanisms, including the sliding filament theory, and discusses muscle fatigue and the effects of exercise on muscle performance. Additionally, the document covers muscle movements, naming conventions, and examples of various muscles within different body regions.