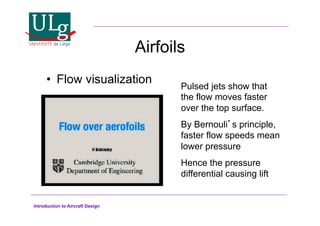

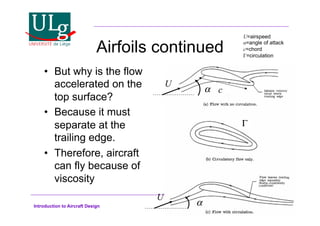

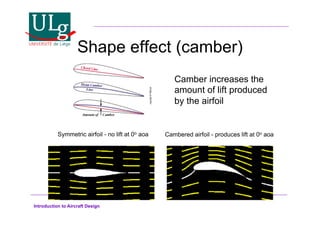

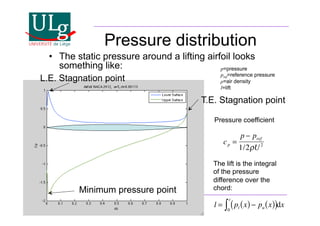

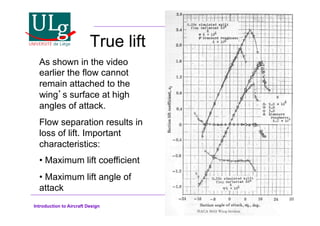

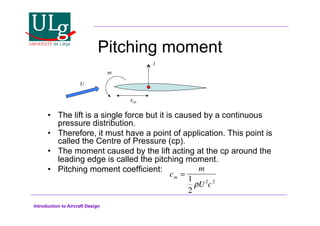

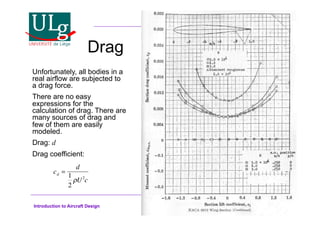

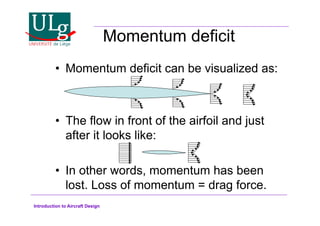

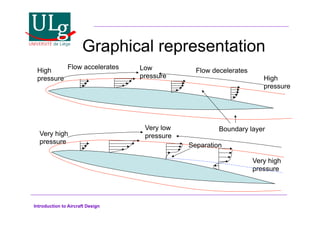

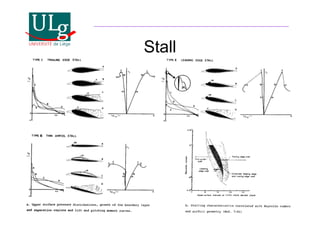

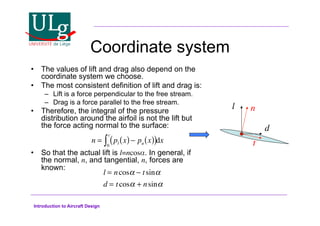

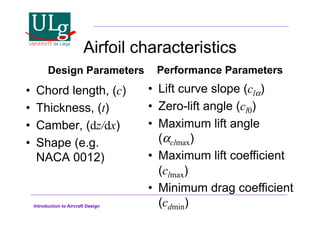

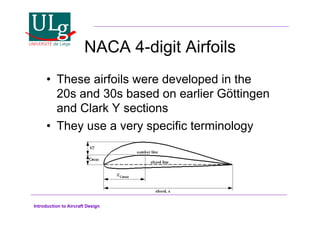

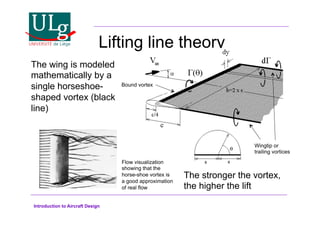

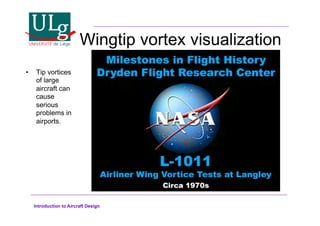

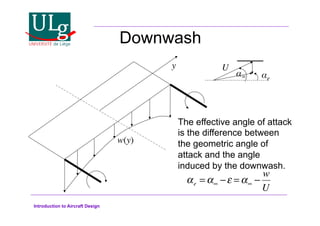

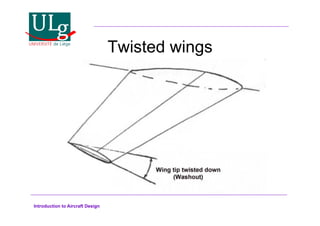

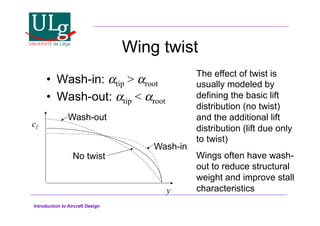

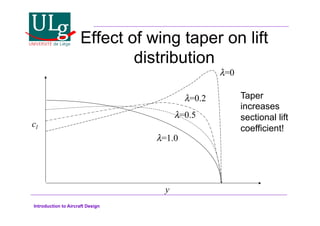

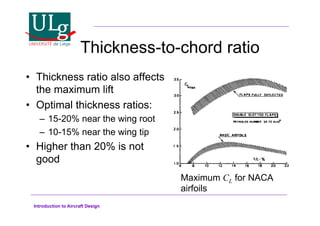

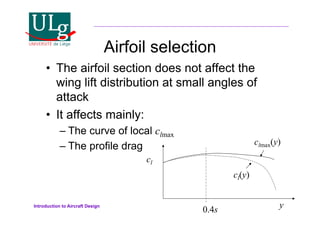

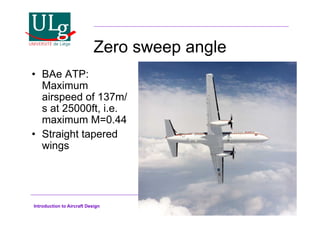

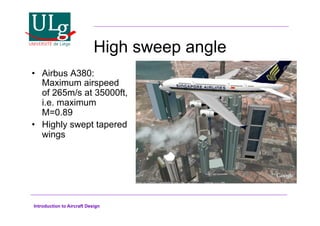

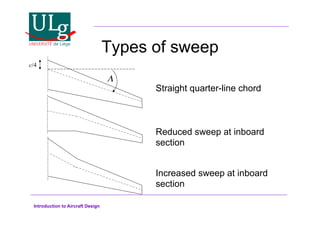

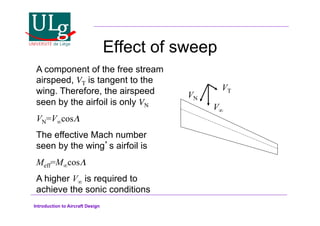

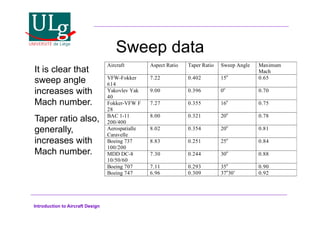

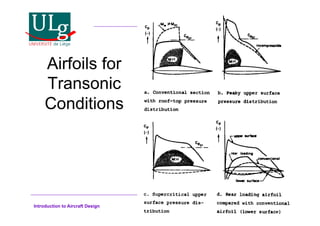

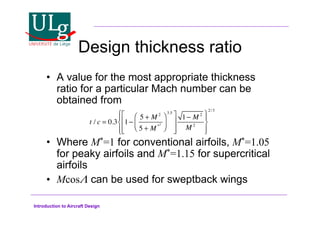

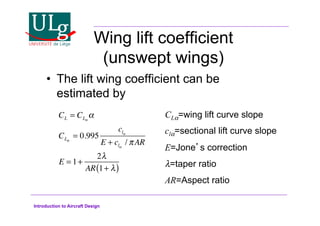

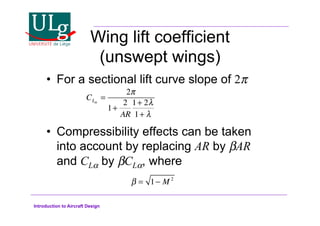

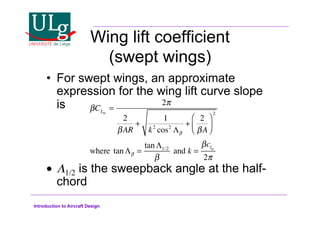

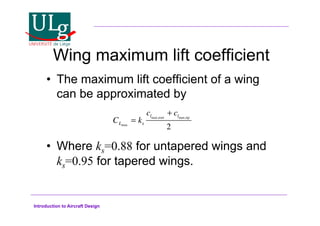

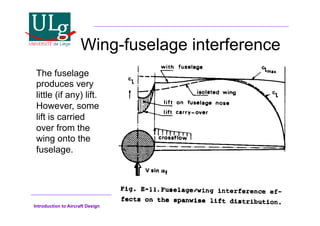

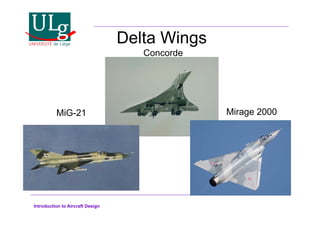

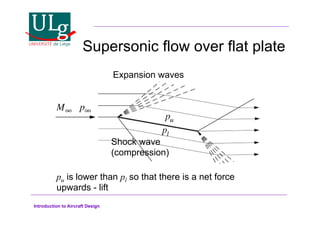

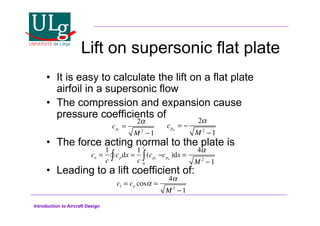

This document provides an introduction to aircraft design, focusing on aerodynamics, including the forces and moments acting on air vehicles such as airplanes, helicopters, and gliders. It explains the principles of lift generation, drag, airfoil characteristics, and various design parameters that influence aircraft performance. The document emphasizes the importance of understanding aerodynamic concepts for effective and safe aircraft design.