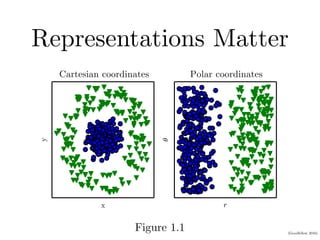

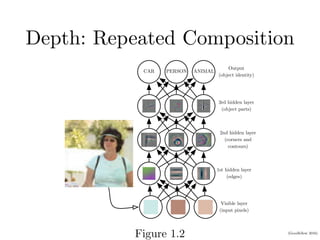

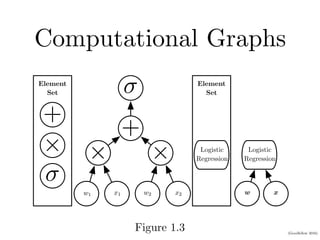

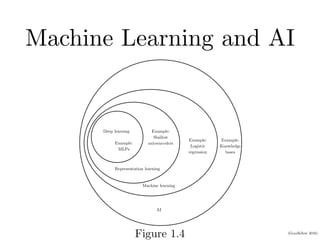

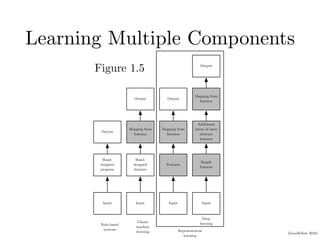

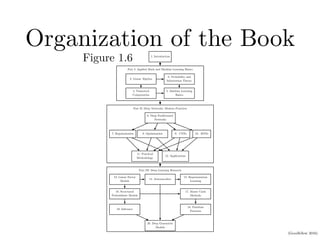

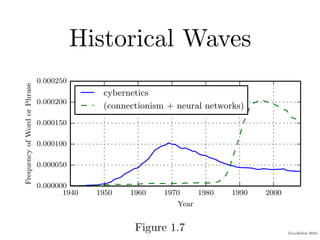

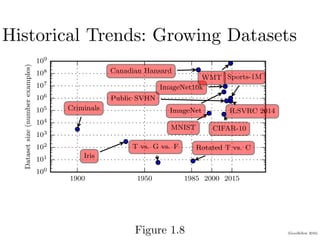

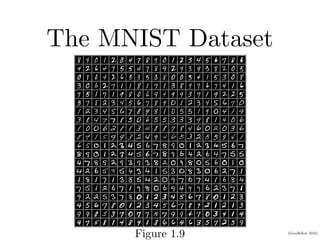

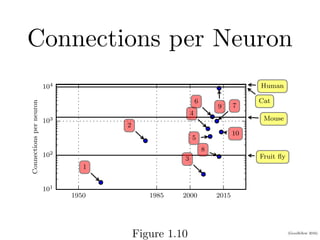

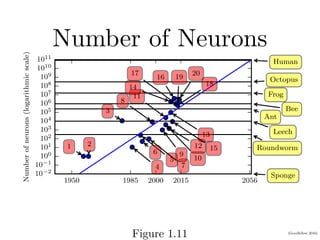

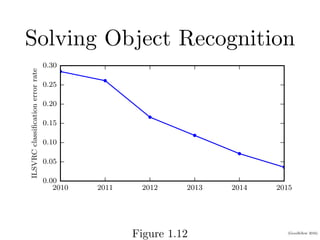

Chapter 1 of the Deep Learning book introduces key concepts and representations in machine learning and deep learning, illustrating how sensory input data is processed through different layers of a deep learning model. It discusses the evolution of neural networks, the increase in dataset sizes, and the historical trends in artificial intelligence over the decades. Additionally, it outlines the organization of the book and various methods and architectures used in deep learning.