INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES International .docx

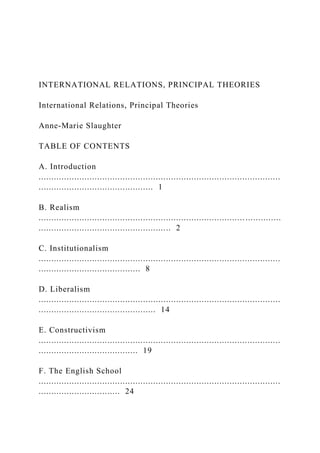

- 1. INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES International Relations, Principal Theories Anne-Marie Slaughter TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Introduction ............................................................................................... ............................................. 1 B. Realism ............................................................................................... .................................................... 2 C. Institutionalism ............................................................................................... ........................................ 8 D. Liberalism ............................................................................................... .............................................. 14 E. Constructivism ............................................................................................... ....................................... 19 F. The English School ............................................................................................... ................................ 24

- 2. G. Critical Approaches ............................................................................................... ............................... 26 H. Conclusion ............................................................................................... ............................................. 28 A. Introduction 1 The study of international relations takes a wide range of theoretical approaches. Some emerge from within the discipline itself; others have been imported, in whole or in part, from disciplines such as economics or sociology. Indeed, few social scientific theories have not been applied to the study of relations amongst nations. Many theories of international relations are internally and externally contested, and few scholars believe only in one or another. In spite of this diversity, several major schools of thought are discernable, differentiated principally by the variables they emphasize—eg military power, material interests, or ideological beliefs. B. Realism 2 For Realists (sometimes termed ‘structural Realists’ or

- 3. ‘Neorealists’, as opposed to the earlier ‘classical Realists’) the international system is defined by anarchy—the absence of a central authority (Waltz). States are sovereign and thus autonomous of each other; no inherent structure or society can emerge or even exist to order relations between them. They are bound only by forcible → coercion or their own → consent. 3 In such an anarchic system, State power is the key—indeed, the only—variable of interest, because only through power can States defend themselves and hope to survive. Realism can understand power in a variety of ways—eg militarily, economically, diplomatically—but ultimately emphasizes the distribution of coercive material capacity as the determinant of international politics. 4 This vision of the world rests on four assumptions (Mearsheimer 1994). First, Realists claim that survival is the principal goal of every State. Foreign invasion and occupation are thus the most pressing threats that any State faces. Even if domestic interests, strategic

- 4. culture, or commitment to a set of national ideals would dictate more benevolent or co- operative international goals, the anarchy of the international system requires that States constantly ensure that they have sufficient power to defend themselves and advance their material interests necessary for survival. Second, Realists hold States to be rational actors. This means that, given the goal of survival, States will act as best they can in order to maximize their likelihood of continuing to exist. Third, Realists assume that all States possess some military capacity, and no State knows what its neighbors intend precisely. The world, in other words, is dangerous and uncertain. Fourth, in such a world it is the Great Powers—the States with most economic clout and, especially, military might, that INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES are decisive. In this view international relations is essentially a story of Great Power politics.

- 5. 5 Realists also diverge on some issues. So-called offensive Realists maintain that, in order to ensure survival, States will seek to maximize their power relative to others (Mearsheimer 2001). If rival countries possess enough power to threaten a State, it can never be safe. → Hegemony is thus the best strategy for a country to pursue, if it can. Defensive Realists, in contrast, believe that domination is an unwise strategy for State survival (Waltz 1979). They note that seeking hegemony may bring a State into dangerous conflicts with its peers. Instead, defensive Realists emphasize the stability of → balance of power systems, where a roughly equal distribution of power amongst States ensures that none will risk attacking another. ‘Polarity’—the distribution of power amongst the Great Powers—is thus a key concept in Realist theory. 6 Realists’ overriding emphasis on anarchy and power leads them to a dim view of international law and international institutions (Mearsheimer 1994). Indeed, Realists

- 6. believe such facets of international politics to be merely epiphenomenal; that is, they reflect the balance of power, but do not constrain or influence State behaviour. In an anarchic system with no hierarchical authority, Realists argue that law can only be enforced through State power. But why would any State choose to expend its precious power on enforcement unless it had a direct material interest in the outcome? And if enforcement is impossible and cheating likely, why would any State agree to co-operate through a treaty or institution in the first place? 7 Thus States may create international law and international institutions, and may enforce the rules they codify. However, it is not the rules themselves that determine why a State acts a particular way, but instead the underlying material interests and power relations. International law is thus a symptom of State behaviour, not a cause. C. Institutionalism 8 Institutionalists share many of Realism’s assumptions about

- 7. the international system— that it is anarchic, that States are self-interested, rational actors seeking to survive while increasing their material conditions, and that uncertainty pervades relations between countries. However, Institutionalism relies on microeconomic theory and game theory to reach a radically different conclusion—that co-operation between nations is possible. 9 The central insight is that co-operation may be a rational, self-interested strategy for countries to pursue under certain conditions (Keohane 1984). Consider two trading partners. If both countries lower their tariffs they will trade more and each will become more prosperous, but neither wants to lower barriers unless it can be sure the other will too. Realists doubt such co-operation can be sustained in the absence of coercive power because both countries would have incentives to say they are opening to trade, dump their goods onto the other country’s markets, and not allow any imports. 10 Institutionalists, in contrast, argue that institutions—defined

- 8. as a set of rules, norms, practices and decision-making procedures that shape expectations—can overcome the uncertainty that undermines co-operation. First, institutions extend the time horizon of interactions, creating an iterated game rather than a single round. Countries agreeing on ad hoc tariffs may indeed benefit from tricking their neighbors in any one round of negotiations. But countries that know they must interact with the same partners repeatedly through an institution will instead have incentives to comply with agreements in the short term so that they might continue to extract the benefits of co- operation in the long term. INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES Institutions thus enhance the utility of a good reputation to countries; they also make punishment more credible. 11 Second, Institutionalists argue that institutions increase information about State behaviour. Recall that uncertainty is a significant reason

- 9. Realists doubt co-operation can be sustained. Institutions collect information about State behaviour and often make judgments of compliance or non-compliance with particular rules. States thus know they will not be able to ‘get away with it’ if they do not comply with a given rule. 12 Third, Institutionalists note that institutions can greatly increase efficiency. It is costly for States to negotiate with one another on an ad hoc basis. Institutions can reduce the transaction costs of co-ordination by providing a centralized forum in which States can meet. They also provide ‘focal points’—established rules and norms—that allow a wide array of States to quickly settle on a certain course of action. Institutionalism thus provides an explanation for international co-operation based on the same theoretical assumptions that lead Realists to be skeptical of international law and institutions. 13 One way for international lawyers to understand Institutionalism is as a rationalist theoretical and empirical account of how and why international

- 10. law works. Many of the conclusions reached by Institutionalist scholars will not be surprising to international lawyers, most of whom have long understood the role that → reciprocity and reputation play in bolstering international legal obligations. At its best, however, Institutionalist insights, backed up by careful empirical studies of international institutions broadly defined, can help international lawyers and policymakers in designing more effective and durable institutions and regimes. D. Liberalism 14 Liberalism makes for a more complex and less cohesive body of theory than Realism or Institutionalism. The basic insight of the theory is that the national characteristics of individual States matter for their international relations. This view contrasts sharply with both Realist and Institutionalist accounts, in which all States have essentially the same goals and behaviours (at least internationally)—self-interested actors pursuing wealth or

- 11. survival. Liberal theorists have often emphasized the unique behaviour of liberal States, though more recent work has sought to extend the theory to a general domestic characteristics-based explanation of international relations. 15 One of the most prominent developments within liberal theory has been the phenomenon known as the democratic peace (Doyle). First imagined by Immanuel Kant, the democratic peace describes the absence of war between liberal States, defined as mature liberal democracies. Scholars have subjected this claim to extensive statistical analysis and found, with perhaps the exception of a few borderline cases, it to hold (Brown Lynn- Jones and Miller). Less clear, however, is the theory behind this empirical fact. Theorists of international relations have yet to create a compelling theory of why democratic States do not fight each other. Moreover, the road to the democratic peace may be a particularly bloody one; Edward Mansfield and Jack Snyder have demonstrated convincingly that democratizing States are more likely to go to war than either

- 12. autocracies or liberal democracies. 16 Andrew Moravcsik has developed a more general liberal theory of international relations, based on three core assumptions: (i) individuals and private groups, not States, are the fundamental actors in world politics (→ Non-State Actors); (ii) States represent some dominant subset of domestic society, whose interests they serve; and (iii) the configuration of these preferences across the international system determines State INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES behaviour (Moravcsik). Concerns about the distribution of power or the role of information are taken as fixed constraints on the interplay of socially-derived State preferences. 17 In this view States are not simply ‘black boxes’ seeking to survive and prosper in an anarchic system. They are configurations of individual and group interests who then

- 13. project those interests into the international system through a particular kind of government. Survival may very well remain a key goal. But commercial interests or ideological beliefs may also be important. 18 Liberal theories are often challenging for international lawyers, because international law has few mechanisms for taking the nature of domestic preferences or regime-type into account. These theories are most useful as sources of insight in designing international institutions, such as courts, that are intended to have an impact on domestic politics or to link up to domestic institutions. The complementary-based jurisdiction of the → International Criminal Court (ICC) is a case in point; understanding the commission of war crimes or crimes against humanity in terms of the domestic structure of a government—typically an absence of any checks and balances— can help lawyers understand why complementary jurisdiction may have a greater impact on the strength of

- 14. a domestic judicial system over the long term than primary jurisdiction (→ International Criminal Courts and Tribunals, Complementarity and Jurisdiction). E. Constructivism 19 Constructivism is not a theory, but rather an ontology: A set of assumptions about the world and human motivation and agency. Its counterpart is not Realism, Institutionalism, or Liberalism, but rather Rationalism. By challenging the rationalist framework that undergirds many theories of international relations, Constructivists create constructivist alternatives in each of these families of theories. 20 In the Constructivist account, the variables of interest to scholars—eg military power, trade relations, international institutions, or domestic preferences—are not important because they are objective facts about the world, but rather because they have certain social meanings (Wendt 2000). This meaning is constructed from a complex and specific mix of history, ideas, norms, and beliefs which scholars must understand if they are to

- 15. explain State behaviour. For example, Constructivists argue that the nuclear arsenals of the United Kingdom and China, though comparably destructive, have very different meanings to the United States that translate into very different patterns of interaction (Wendt 1995). To take another example, Iain Johnston argues that China has traditionally acted according to Realist assumptions in international relations, but based not on the objective structure of the international system but rather on a specific historical strategic culture. 21 A focus on the social context in which international relations occur leads Constructivists to emphasize issues of identity and belief (for this reason Constructivist theories are sometimes called ideational). The perception of friends and enemies, in-groups and out- groups, fairness and justice all become key determinant of a State’s behaviour. While some Constructivists would accept that States are self- interested, rational actors, they

- 16. would stress that varying identities and beliefs belie the simplistic notions of rationality under which States pursue simply survival, power, or wealth. 22 Constructivism is also attentive to the role of social norms in international politics. Following March and Olsen, Constructivists distinguish between a ‘logic of consequences’—where actions are rationally chosen to maximize the interests of a INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES State—and ‘logic of appropriateness’, where rationality is heavily mediated by social norms. For example, Constructivists would argue that the norm of State sovereignty has profoundly influenced international relations, creating a predisposition for non- interference that precedes any cost-benefit analysis States may undertake. These arguments fit under the Institutionalist rubric of explaining international co-operation, but based on constructed attitudes rather than the rational pursuit of objective interests.

- 17. 23 Perhaps because of their interest in beliefs and ideology, Constructivism has also emphasized the role of non-State actors more than other approaches. For example, scholars have noted the role of transnational actors like NGOs or transnational corporations in altering State beliefs about issues like the use of land mines in war or international trade. Such ‘norm entrepreneurs’ are able to influence State behaviour through rhetoric or other forms of lobbying, persuasion, and shaming (Keck and Sikkink). Constructivists have also noted the role of international institutions as actors in their own right. While Institutionalist theories, for example, see institutions largely as the passive tools of States, Constructivism notes that international bureaucracies may seek to pursue their own interests (eg free trade or → human rights protection) even against the wishes of the States that created them (Barnett and Finnemore). F. The English School 24 The English School shares many of Constructivism’s critiques of rationalist theories of

- 18. international relations. It also emphasizes the centrality of international society and social meanings to the study of world politics (Bull). Fundamentally, however, it does not seek to create testable hypotheses about State behaviour as the other theories do. Instead, its goals are more similar to those of a historian. Detailed observation and rich interpretation is favored over general explanatory models. Hedley Bull, for instance, a leading English School scholar, argued that international law was one of five central institutions mediating the impact of international anarchy and instead creating ‘an anarchical society’. 25 Given their emphasis on context and interpretive methods, it is no surprise that English School writers hold historical understandings to be critical to the study of world politics. It is not enough simply to know the balance of power in the international system, as the Realists would have it. We must also know what preceded that system, how the States involved came to be where they are today, and what might threaten or motivate them in

- 19. the future. Domestic politics are also important, as are norms and ideologies. G. Critical Approaches 26 The dominant international relations theories and their underlying positivist epistemology have been challenged from a range of perspectives. Scholars working in Marxist, feminist, post-colonial, and ecological fields have all put forward critiques of international relations’ explanations of State behaviour (→ Colonialism; → Developing Country Approach to International Law; → Feminism, Approach to International Law). Most of these critiques share a concern with the construction of power and the State, which theories like Realism or Institutionalism tend to take for granted. 27 For example, Marxist scholars perceive the emphasis on State-to-State relations as obscuring the more fundamental dynamics of global class relations (→ Marxism). Only by understanding the interests and behaviour of global capital can we make sense of State

- 20. behaviour, they argue (Cox and Sinclair). Similarly, feminists have sought to explain aspects of State behaviour and its effects by emphasizing gender as a variable of interest INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES (Ackerly Stern and True). This focus has lead, for example, to notions of security that move beyond State security (of paramount importance to Realists) to notions of human security. In such a perspective the effects of war, for example, reach far beyond the battlefield to family life and other aspects of social relations. H. Conclusion 28 While many theories of international relations are fiercely contested, it is usually inappropriate to see them as rivals over some universal truth about world politics. Rather, each rests on certain assumptions and epistemologies, is constrained within certain specified conditions, and pursues its own analytic goal. While various theories may lead to more or less compelling conclusions about international

- 21. relations, none is definitively ‘right’ or ‘wrong’. Rather, each possesses some tools that can be of use to students of international politics in examining and analyzing rich, multi- causal phenomena. SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY I Kant Zum ewigen Frieden (Friedrich Nicolovius Königsberg 1795, reprinted by Reclam Ditzingen 1998). H Bull The Anarchical Society: A Study of Order in World Politics (Macmillan London 1977). KN Waltz Theory of International Politics (Addison-Wesley Reading 1979). RO Keohane After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy (Princeton University Press Princeton 1984). RD Putnam ‘Diplomacy and Domestic Politics: The Logic of Two-Level Games’ (1988) 42 IntlOrg 427–60. JG March and JP Olsen Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics (The Free Press New York 1989). DA Baldwin (ed) Neorealism and Neoliberalism: The Contemporary Debate (Columbia University Press New York 1993).

- 22. JJ Mearsheimer ‘The False Promise of International Institutions’ (1994) 19(3) International Security 5–49. JD Fearon ‘Rationalist Explanations for War’ (1995) 49 IntlOrg 379–414. AI Johnston Cultural Realism: Strategic Culture and Grand Strategy in Chinese History (Princeton University Press Princeton 1995). A Wendt ‘Constructing International Politics’ (1995) 20(1) International Security 71–81. ME Brown SM Lynn-Jones and SE Miller (eds) Debating the Democratic Peace (MIT Cambridge 1996). RW Cox and TJ Sinclair Approaches to World Order (CUP Cambridge 1996). MW Doyle Ways of War and Peace: Realism, Liberalism, and Socialism (Norton New York 1997). HV Milner Interests, Institutions, and Information: Domestic Politics and International Relations (Princeton University Press Princeton 1997). A Moravcsik ‘Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theory of International Politics’ (1997) 51 IntlOrg 513–53. ME Keck and K Sikkink Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics (Cornell

- 23. University Press Ithaca 1998). R Powell In the Shadow of Power: States and Strategies in International Politics (Princeton University Press Princeton 1999). KOW Abbott and others ‘The Concept of Legalization’ (2000) 54 IntlOrg 401–19. A Wendt Social Theory of International Politics (CUP Cambridge 2000). B Koremenos (ed) ‘The Rational Design of International Institutions’ (2001) 55 IntlOrg 761–1103. JJ Mearsheimer The Tragedy of Great Power Politics (Norton New York 2001). MN Barnett and M Finnemore Rules for the World: International Organizations in Global Politics (Cornell University Press Ithaca 2004). ED Mansfield and J Snyder Electing to Fight: Why Emerging Democracies Go to War (MIT Cambridge 2005). BA Ackerly M Stern and J True (eds) Feminist Methodologies for International Relations (CUP Cambridge 2006).

- 24. INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS, PRINCIPAL THEORIES Published in: Wolfrum, R. (Ed.) Max Planck Encyclopedia of Public International Law (Oxford University Press, 2011) www.mpepil.com http://www.mpepil.com/ International Relations: One World, Many Theories by Stephen M. Walt W h y should policymakers and practitioners care about the scholarly study of interna- tional affairs? Those who conduct foreign policy often dismiss academic theorists (frequently, one must admit, with good reason), but there is an inescapable link between the abstract worm of theory and the real worm of policy. We need theories to make sense of the blizzard of information that bom- bards us daily. Even policymakers who are contemptuous of "theory" must rely on their o w n (often unstated) ideas about how the

- 25. world works in order to decide what to do. It is hard to make good policy if one's basic organizing principles are flawed, just as it is hard to construct good theories without knowing a lot about the real world. Everyone uses t h e o r i e s - - w h e t h e r he or she knows it or n o t - - a n d disagreements about policy usually rest on more fundamental disagreements about the basic forces that shape international outcomes. Take, for example, the current debate on how to respond to China. From one perspective, C h i n a s ascent is the latest example of the ten- STEPHEN M . W A L T is professor of political science and master of the social science colle- giate division at the University of Chicago. He is a member of FOREIGN POLICY's editorial board. S P R I N G 1 9 9 8 29 International Relations dency for rising powers to alter the global balance of power in poten- tially dangerous ways, especially as their growing influence makes them more ambitious. From another perspective, the key to China's future conduct is whether its behavior will be modified by its

- 26. integration into world markets and by the (inevitable?) spread of democratic principles. From yet another viewpoint, relations between China and the rest of the world will be shaped by issues of culture and identity: Will China see itself (and be seen by others) as a normal member of the world com- munity or a singular society that deserves special treatment? In the same way, the debate over NA'rO expansion looks different depending on which theory one employs. From a "realist" perspective, N A T O expansion is an effort to extend Western influence-- well beyond the traditional sphere of U.S. vital interests--during a period of Russ- Jan weakness and is likely to provoke a harsh response from Moscow. From a liberal perspective, however, expansion will reinforce the nascent democracies of Central Europe and extend NATO's conflict- management mechanisms to a potentially turbulent region. A third view might stress the value of incorporating the Czech Republic, Hun- gary, and Poland within the Western security community, whose mem- bers share a common identity that has made war largely unthinkable. No single approach can capture all the complexity of contemporary

- 27. world politics. Therefore, we are better off with a diverse array of com- peting ideas rather than a single theoretical orthodoxy. Competition between theories helps reveal their strengths and weaknesses and spurs subsequent refinements, while revealing flaws in conventional wisdom. Although we should take care to emphasize inventiveness over invective, we should welcome and encourage the heterogeneity of contemporary scholarship. W H E n E AnE WE COMING FnOM? The study of international affairs is best understood as a protracted com- petition between the realist, liberal, and radical traditions. Realism empha- sizes the enduring propensity for conflict between states; liberalism identifies several ways to mitigate these conflictive tendencies; and the radical tradition describes how the entire system of state relations might be transformed. The boundaries between these traditions are somewhat fuzzy and a number of important works do not fit neatly into any of them, but debates within and among them have largely defmed the discipline. 30 F O R E I G N P O L I C Y

- 28. Walt Rea//sm Realism was the dominant theoretical tradition throughout the Cold War. It depicts international affairs as a struggle for power among self- interested states and is generally pessimistic about the prospects for eliminating conflict and war. Realism dominated in the Cold War years because it provided simple but powerful explanations for war, alliances, imperialism, obstacles to cooperation, and other international phenom- ena, and because its emphasis on competition was consistent with the central features of the American-Soviet rivalry. Realism is not a single theory, of course, and realist thought evolved considerably throughout the Cold War. "Classical" realists such as Hans Morgenthau and Reinhold Niebuhr believed that states, like human beings, had an innate desire to dominate others, which led them to fight wars. Morgenthau also stressed the virtues of the classical, multipolat; balance-of-power system and saw the bipolar rivalry between the Unit- ed States and the Soviet Union as especially dangerous. By contrast, the "neorealist" theory advanced by Kenneth Waltz ignored human nature and focused on the effects of the

- 29. international system. For Waltz, the international system consisted of a number of great powers, each seeking to survive. Because the system is anarchic (i.e., there is no central authority to protect states from one another), each state has to survive on its own. Waltz argued that this condition would lead weaker states to balance against, rather than bandwagon with, more powerful rivals. A n d contrary to Morgenthau, he claimed that bipolarity was more stable than multipolarity. A n important refinement to realism was the addition of offense- defense theory, as laid out by Robert Jervis, George Quester, and Stephen Van Evem. These scholars argued that war was more likely when states could conquer each other easily. W h e n defense was easier than offense, however, security was more plentiful, incentives to expand declined, and cooperation could blossom. A n d if defense had the advantage, and states could distinguish between offensive and defensive weapons, then states could acquire the means to defend themselves without threatening others, thereby dampening the effects of anarchy. For these "defensive" realists, states merely sought to survive and great

- 30. powers could guarantee their security by forming balancing alliances and choosing defensive military postures (such as retaliatory nuclear forces). Not surprisingly, Waltz and most other neorealists believed that the United States was extremely secure for most of the Cold War. Their S P R I N G 1 9 9 8 31 International Relations principle fear was that it might squander its favorable position by adopt- ing an overly aggressive foreign policy. Thus, by the end of the Cold War, realism had moved away from Morgenthau's dark brooding about human nature and taken on a slightly more optimistic tone. Liberalism The principal challenge to realism came from a broad family of liber- al theories. One strand of liberal thought argued that economic inter- dependence would discourage states from using force against each other because warfare would threaten each side's prosperity. A second strand, often associated with President Woodrow Wilson, saw the spread of democracy as the key to world peace, based on the claim that

- 31. democratic states were inherently more peaceful than authoritarian states. A third, more recent theory argued that international institutions such as the International Energy Agency and the Inter- national Monetary Fund could help overcome selfish state behavior, mainly by encouraging states to forego immediate gains for the greater benefits of enduring cooperation. Although some liberals flirted with the idea that new transnational actors, especially the multinational corporation, were gradually encroaching on the power of states, liberalism generally saw states as the central players in international affairs. All liberal theories implied that cooperation was more pervasive than even the defensive version of real- ism allowed, but each view offered a different recipe for promoting it. R a d / c d Ap~oaches Until the 1980s, marxism was the main alternative to the mainstream realist and liberal traditions. Where realism and liberalism took the state system for granted, marxism offered both a different explanation for international conflict and a blueprint for fundamentally transform- ing the existing international order. Orthodox marxist theory saw capitalism as the central cause of inter-

- 32. national conflict. Capitalist states battled each other as a consequence of their incessant struggle for profits and battled socialist states because they saw in them the seeds of their own destruction. Neomarxist "dependency" theory, by contrast, focused on relations between advanced capitalist powers and less developed states and argued that the former--aided by an unholy alliance with the ruling classes of the developing world had grown rich by exploiting the latter. The solu- 32 F O R E I G N P O L I C Y International Relations tion was to overthrow these parasitic 61ites and install a revolutionary government committed to autonomous development. Both of these theories were largely discredited before the Cold War even ended. The extensive history of economic and military coopera- tion among the advanced industrial powers showed that capitalism did not inevitably lead to conflict. The bitter schisms that divided the communist world showed that socialism did not always promote har- mony. Dependency theory suffered similar empirical setbacks as it became increasingly clear that, first, active participation in the

- 33. world economy was a better route to prosperity than autonomous socialist development; and, second, many developing countries proved them- selves quite capable of bargaining successfully with multinational cor- porations and other capitalist institutions. As marxism succumbed to its various failings, its mantle was assumed by a group of theorists who borrowed heavily from the wave of postmodem writings in literary criticism and social theory. This "deconstructionist" approach was openly skeptical of the effort to devise general or universal theories such as realism or liberalism. Indeed, its proponents emphasized the importance of language and discourse in shaping social outcomes. However, because these scholars focused initially on criticizing the mainstream paradigms but did not offer positive alternatives to them, they remained a self- consciously dissident minority for most of the 1980s. Domestic Politics Not all Cold War scholarship on international affairs fit neatly into the realist, liberal, or marxist paradigms. In particular, a number of impor- tant works focused on the characteristics of states, governmental orga- nizations, or individual leaders. The democratic strand of liberal

- 34. theory fits under this heading, as do the efforts of scholars such as Graham Allison and John Steinbruner to use organization theory and bureau- cratic politics to explain foreign policy behavior, and those of Jervis, Irving Janis, and others, which applied social and cognitive psycholo- gy. For the most part, these efforts did not seek to provide a general the- ory of international behavior but to identify other factors that might lead states to behave contrary to the predictions of the realist or liber- al approaches. Thus, much of this literature should be regarded as a complement to the three main paradigms rather than as a rival approach for analysis of the international system as a whole. 34 F O R E I G N P O L I C Y Walt NEW W R I N K L E S IN O L D PARADIGMS Scholarship on intemational affairs has diversified significantly since the end of the Cold War. Non-American voices are more prominent, a wider range of methods and theories are seen as legitimate, and new issues such as ethnic conflict, the environment, and the future of the

- 35. state have been placed on the agenda of scholars everywhere. Yet the sense of d~j~ vu is equally striking. Instead of resolving the strug- gle between competing theoretical traditions, the end of the Cold War has merely launched a new series of debates. Ironically, even as many societies embrace similar ideals of democracy, free markets, and human rights, the scholars who study these developments are more divided than ever. Rea//sm Redux Although the end of the Cold War led a few writers to declare that realism was destined for the academic scrapheap, rumors of its demise have been largely exaggerated. A recent contribution of realist theory is its attention to the problem of relative and absolute gains. Responding to the institutionalists' claim that international institutions would enable states to forego short-term advantages for the sake of greater long-term gains, realists such as Joseph Grieco and Stephen Krasner point out that anarchy forces states to worry about both the absolute gains from cooperation and the way that gains are distributed among participants. The logic is straightforward: If one state reaps larger gains than its partners, it will gradually become

- 36. stronger, and its partners will eventually become more vulnerable. Realists have also been quick to explore a variety of new issues. Barry Posen offers a realist explanation for ethnic conflict, noting that the breakup of multiethnic states could place rival ethnic groups in an anar- chic setting, thereby triggering intense fears and tempting each group to use force to improve its relative position. This problem would be par- ticularly severe when each group's territory contained enclaves inhabit- ed by their ethnic rivals--as in the former Yugoslavia because each side would be tempted to "cleanse" (preemptively) these alien minori- ties and expand to incorporate any others from their ethnic group that lay outside their borders. Realists have also cautioned that N^TO, absent a clear enemy, would likely face increasing strains and that expanding its presence eastward would jeopardize relations with Russia. Finally, scholars such as Michael Mastanduno have argued that U.S. S P R I N O 1 9 9 8 35 International Relations

- 37. Waiting for Mr. X T h e post-Cold War world still awaits its "X" article. Although many have tried, no one has managed to pen the sort of compelling analysis that George Kennan provided for an earlier era, when he articulated the theory of containment. Instead of a single new vision, the most impor- tant development in post-Cold War writings on world affairs is the con- tinuing clash between those who believe world politics has been (or is being) fundamentally transformed and those who believe that the future will look a lot like the past. Scholars who see the end of the Cold War as a watershed fall into two distinct groups. Many experts still see the state as the main actor but believe that the agenda of states is shifting from military competi- tion to economic competitiveness, domestic welfare, and environmen- tal protection. Thus, President Bill Clinton has embraced the view that "enlightened self-interest [and] shared v a l u e s . . , will compel us to cooperate in more constructive ways." Some writers attribute this change to the spread of democracy, others to the nuclear stalemate, and still others to changes in international norms. A n even more radical perspective questions whether the state

- 38. is still the most important international actor. Jessica Mathews believes that "the absolutes of the Westphalian system [of] territorially fixed s t a t e s . . , are all dissolving," and John Ruggie argues that we do not even have a vocabulary that can adequately describe the new forces that (he believes) are transforming contemporary world politics. Although there is still no consensus on the causes of this trend, the view that states are of decreasing relevance is surprisingly common among academics, journalists, and policy wonks. Prominent realists such as Christopher Layne and Kenneth Waltz continue to give the state pride of place and predict a return to familiar patterns of great power competition. Similarly, Robert Keohane and other institutionalists also emphasize the central role of the state and argue that institutions such as the European Union and NATO are important precisely because they provide continuity in the midst of dra- matic political shifts. These authors all regard the end of the Cold War as a far-reaching shift in the global balance of power but do not see it as a qualitative transformation in the basic nature of world politics. W h o is right? Too soon to tell, but the debate bears watching

- 39. in the years to come. - - S . W . 36 F O R E I G N P O L I C Y Wak foreign policy is generally consistent with realist principles, insofar as its actions are still designed to preserve U.S. predominance and to shape a postwar order that advances American interests. The most interesting conceptual development within the realist par- adigm has been the emerging split between the "defensive" and "offen- sive" strands of thought. Defensive realists such as Waltz, Van Ever-a, and Jack Snyder assumed that states had little intrinsic interest in mili- tary conquest and argued that the costs of expansion generally out- weighed the benefits. Accordingly, they maintained that great power wars occurred largely because domestic groups fostered exaggerated per- ceptions of threat and an excessive faith in the efficacy of military force. This view is now being challenged along several fronts. First, as Ran- dall Schweller notes, the neorealist assumption that states

- 40. merely seek to survive "stacked the deck" in favor of the status quo because it pre- cluded the threat of predatory revisionist states nations such as Adolf Hitler's Germany or Napoleon Bonaparte's France that "value what they covet far more than what they possess" and are willing to risk anni- hilation to achieve their aims. Second, Peter Liberman, in his book Does Conquest Pay?, uses a number of historical cases--such as the Nazi occupation of Western Europe and Soviet hegemony over Eastern Europe--to show that the benefits of conquest often exceed the costs, thereby casting doubt on the claim that military expansion is no longer cost-effective. Third, offensive realists such as Eric Labs, John Mearsheimer, and Fareed Zakaria argue that anarchy encourages all states to try to maximize their relative strength simply because no state can ever be sure when a truly revisionist power might emerge. These differences help explain why realists disagree over issues such as the future of Europe. For defensive realists such as Van Evem, war is rarely profitable and usually results from militarism, hypernationalism, or some other distorting domestic factor. Because Van Evera believes such forces are largely absent in post-Cold War Europe, he concludes

- 41. that the region is "primed for peace." By contrast, Mearsheimer and other offensive realists believe that anarchy forces great powers to com- pete irrespective of their internal characteristics and that security com- petition will return to Europe as soon as the U.S. pacifier is withdrawn. New L/re for L/herd/sin The defeat of communism sparked a round of self- congratulation in the West, best exemplified by Francis Fukuyama's infamous claim that S P R I N G 1 9 9 8 37 International Relations COMPETING PARADIGMS Ssvaf-J~erl~lgd slatus CnlIcgrn for power S1nta bohaviec shaped compete c o ~ fur overridden by economic, by 61~ b~efs, power or s e c u ~ paliticd mmiderntions cdleclive norms, (desi/e fur ~'ecpwJly, and s~jnl idm~dliec commilmont to liberal values) States S1otus Individuals (ecpeciaiy ~Jitus)

- 42. Economic and Varies (international Ideas and espe('mlly military instituliens, economic discourse power axdmnge, promntion of democracy) Hans Margenthon, Michael Doyle, Alexander Wench, Kenneth Waltz Robed Keohona John ROwe Main Thec,;i~,~ Pr~ositlon Mab Ueits of Analysb Mab Instrumnts Modern Theorists Representative Modem Works Wall~ T/mory of ~ernat/ona/Po//#cE Maarsbeimer, "Back to i the Future: Imtabil~ly in Europe after the Cold War" (l~rnat/ana/Sea~r/ry, 1990) Keohaon, After Hq~nany Fukuyama, "the [nd of flist~?" (#m'/oon/ /ntea'~, 1989)

- 43. Wendl', "Aonrd~ Is Whm States Make of H' (I.~r~/ona/ OrSan~,a~ 1992); R o s l o ~ & Krmeclnd, "Under- standing Omogm in Intumu~al Politics" [Inturnaliond 1994) Post-Cold War Resurgence of Increased co~erafim Agonslic became ii Predldim overt great power as lib~al values, free cannot prndia Ibe compelilion markets, and intema- content oF ideas fional in~ntiens ~onl Mab Lknitation Daes not account for Tends Io ignore tho Belier at describing 1he intemmienal change role of power past Ilmn anticipaling the future 3 8 F O R E I G N P O L I C Y Walt h u m a n k i n d had n o w reached the "end of history." History has paid lit- tle attention to this boast, but the triumph of the West did give a notable boost to all three swands of liberal thought.

- 44. By far the most interesting and important development has been the lively debate o n the "democratic peace." Although the most recent phase of this debate had begun e v e n before the Soviet U n i o n collapsed, it became more influential as the number of democracies began to increase and as evidence of this relationship began to accumulate. Democratic peace theory is a refinement of the earlier claim that democracies were inherently more peaceful t h a n autocratic states. It rests on the belief that although democracies seem to fight wars as often as other states, they rarely, ff ever, fight one another. Scholars such as Michael Doyle, James Lee Ray, and Bruce Russetr have offered a number of explanations for this tendency, the most popular being that democra- cies embrace norms of compromise that bar the use of force against groups espousing similar principles. It is hard to think of a more influen- tial, recent academic debate, insofar as the belief that "democracies don't fight each other" has been an important justification for the Clinton administration's efforts to enlarge the sphere of democratic rule. It is therefore ironic that faith in the "democratic peace" became the

- 45. basis for U.S. policy just as additional research was beginning to identify several qualifiers to this theory. First, Snyder and Edward Mansfield pointed out that states may be more prone to war w h e n they are in the midst of a democratic transition, which implies that efforts to export democracy might actually make things worse. Second, critics such as Joanne Gowa and David Spiro have argued that the apparent absence of war between democracies is due to the way that democracy has been defined and to the relative dearth of democratic states (especially before 1945). In addition, Christopher Layne has pointed out that w h e n democracies have come close to war in the past their decision to remain at peace ukimately had little do with their shared democratic character. Third, clearcut evidence that democracies do not fight each other is con- fined to the post-1945 era, and, as Gowa has emphasized, the absence of conflict in this period may be due more to their common interest in con- mining the Soviet U n i o n t h a n to shared democratic principles. Liberal institutionalists likewise have continued to adapt their own theories. O n the one hand, the core claims of institutionalist theory have become more modest over time. Institutions are now said to

- 46. facilitate cooperation w h e n it is in each state's interest to do so, but it is widely S P R I N G 1 9 9 8 39 International Relations agreed that they cannot force states to behave in ways that are contrary to the states' own selfish interests. [For further discussion, please see Robert Keohane's article.] O n the other hand, institutionalists such as John Duffield and Robert McCalla have extended the theory into new substantive areas, most notably the study of NAaXg. For these scholars, NATO'S highly institutionalized character helps explain why it has been able to survive and adapt, despite the disappearance of its main adversary. T h e economic strand of liberal theory is still influential as well. In par- ticular, a number of scholars have recently suggested that the "globaliza- tion" of world markets, the rise of transnational networks and nongovernmental organizations, and the rapid spread of global commu- nications technology are undermining the power of states and shifting attention away from military security toward economics and social wel-

- 47. fare. T h e details are novel but the basic logic is familiar: As societies around the globe become enmeshed in a web of economic and social connections, the costs of disrupting these ties will effectively preclude unilateral state actions, especially the use of force. This perspective implies that war will remain a remote possibility among the advanced industrial democracies. It also suggests that bring- ing C h i n a and Russia into the relentless embrace of world capitalism is the best way to promote both prosperity and peace, particularly if this process creates a strong middle class in these states and reinforces pres- sures to democratize. G e t these societies hooked on prosperity and com- petition will be confined to the economic realm. This view has b e e n challenged by scholars who argue that the actu- al scope of "globalization" is modest and that these various transactions still take place in environments that are shaped and regulated by states. Nonetheless, the belief that economic forces are superseding tradition- al great power politics enjoys widespread acceptance among scholars, pundits, and policymakers, and the role of the state is likely to be an important topic for future academic inquiry.

- 48. Constructia~st Theories Whereas realism and liberalism tend to focus on material factors such as power or trade, constructivist approaches emphasize the impact of ideas. Instead of taking the state for granted and assuming that it simply seeks to survive, constructivists regard the interests and identities of states as a highly malleable product of specific historical processes. They pay close attention to the prevailing discourse(s) in society because dis- 40 FOREIGN P O L I C Y Wdt course reflects and shapes beliefs and interests, and establishes accepted norms of behavior. Consequently, constructivism is especially attentive to the sources of change, and this approach has largely replaced marx- ism as the preeminent radical perspective on international affairs. The end of the Cold War played an important role in legitimating constructivist theories because realism and liberalism both failed to anticipate this event and had some trouble explaining it. Construc- tivists had an explanation: Specifically, former president

- 49. Mikhail Gorbachev revolutionized Soviet foreign policy because he embraced new ideas such as "common security." Moreover, given that we live in an era where old norms are being challenged, once clear boundaries are dissolving, and issues of identi- ty are becoming more salient, it is hardly surprising that scholars have been d/awn to approaches that place these issues front and center. From a constructivist perspective, in fact, the central issue in the post-Cold War world is how different groups conceive their identities and interests. Although power is not irrelevant, constructivism emphasizes how ideas and identities are created, how they evolve, and how they shape the way states understand and respond to their situa- tion. Therefore, it matters whether Europeans define themselves pri- marily in national or continental terms; whether Germany and Japan redefine their pasts in ways that encourage their adopting more active international roles; and whether the United States embraces or rejects its identity as "global policeman." Constructivist theories are quite diverse and do not offer a unified set of predictions on any of these issues. At a purely conceptual level,

- 50. Alexander Wendt has argued that the realist conception of anarchy does not adequately explain why conflict occurs between states. The real issue is how anarchy is understood--in Wendt's words, "Anarchy is what states make of it." Another strand of constructivist theory has focused on the future of the territorial state, suggesting that transna- tional communication and shared civic values are undermining tradi- tional national loyalties and creating radically new forms of political association. Other constructivists focus on the role of norms, arguing that international law and other normative principles have eroded ear- lier notions of sovereignty and altered the legitimate purposes for which state power may be employed. The common theme in each of these strands is the capacity of discourse to shape how political actors define themselves and their interests, and thus modify their behavior. S r ' a I N O 1 9 9 8 41 International Relations Domestic Politics Recons/dered As in the Cold War, scholars continue to explore the impact of domes-

- 51. tic politics on the behavior of states. Domestic politics are obviously central to the debate on the democratic peace, and scholars such as Snyder, Jeffrey Frieden, and Helen Milner have examined how domes- tic interest groups can distort the formation of state preferences and lead to suboptimal international behavior. George Downs, David Rocke, and others have also explored how domestic institutions can help states deal with the perennial problem of uncertainty, while students of psy- chology have applied prospect theory and other new tools to explain why decision makers fail to act in a rational fashion. [For further dis- cussion about foreign policy decision making, please see the article by Margaret Hermann and Joe Hagan.] The past decade has also witnessed an explosion of interest in the concept of culture, a development that overlaps with the constructivist emphasis on the importance of ideas and norms. Thus, Thomas Berger and Peter Katzenstein have used cultural variables to explain why Ger- many and Japan have thus far eschewed more self-reliant military poli- cies; Elizabeth Kier has offered a cultural interpretation of British and French military doctrines in the interwar period; and lain Johnston has

- 52. traced continuities in Chinese foreign policy to a deeply rooted form of "cultural realism." Samuel Huntington's dire warnings about an immi- nent "clash of civilizations" are symptomatic of this trend as well, inso- far as his argument rests on the claim that broad cultural affinities are now supplanting national loyalties. Though these and other works define culture in widely varying ways and have yet to provide a full explanation of how it works or how enduring its effects might be, cul- tural perspectives have been very much in vogue during the past five years. This trend is partly a reflection of the broader interest in cultural issues in the academic world (and within the public debate as well) and partly a response to the upsurge in ethnic, nationalist, and cultural con- flicts since the demise of the Soviet Union. T O M O R R O W ' S C O N C E P T U A L T O O L B O X While these debates reflect the diversity of contemporary scholarship on international affairs, there are also obvious signs of convergence. Most real- ists recognize that nationalism, militarism, ethnicity, and other domestic factors are important; liberals acknowledge that power is central to inter- 42 F O R E I G N P O L I C Y

- 53. Wak national behavior; and some constructivists admit that ideas will have greater impact when backed by powerful states and reinforced by enduring material forces. The boundaries of each paradigm are somewhat perme- able, and there is ample opportunity for intellectual arbitrage. W h i c h of these broad perspectives sheds the most light on contem- porary international affairs, and which should policymakers keep most firmly in mind when charting our course into the next century? Although many academics (and more than a few policymakers) are loathe to admit it, realism remains the most compelling general frame- work for understanding international relations. States continue to pay close attention to the balance of power and to worry about the possi- bility of major conflict. Among other things, this enduring preoccupa- tion with power and security explains why many Asians and Europeans are now eager to preserve--and possibly expand--the U.S. military presence in their regions. As Czech president V~iclav Havel has warned, if NATO fails to expand, "we might be heading for a new glob- al c a t a s t r o p h e . . . [which] could cost us all much more

- 54. than the two world wars." These are not the words of a man who believes that great power rivalry has been banished forever. As for the United States, the past decade has shown how much it likes being "number one" and how determined it is to remain in a predominant position. The United States has taken advantage of its current superiori- ty to impose its preferences wherever possible, even at the risk of irritat- ing many of its long-standing allies. It has forced a series of one-sided arms control agreements on Russia, dominated the problematic peace effort in Bosnia, taken steps to expand NATO into Russia's backyard, and become increasingly concemed about the rising power of China. It has called repeatedly for greater reliance on multilateralism and a larger role for international institutions, but has treated agencies such as the United Nations and the World Trade Organization with disdain whenever their actions did not conform to U.S. interests. It refused to join the rest of the world in outlawing the production of landmines and was politely unco- operative at the Kyoto environmental summit. Although U.S. leaders are adept at cloaking their actions in the lofty rhetoric of"world order," naked self-interest lies behind most of them. Thus, the end of the Cold

- 55. War did not bring the end of power politics, and realism is likely to remain the sin- gle most useful instrument in our intellectual toolbox. Yet realism does not explain everything, and a wise leader would also keep insights from the rival paradigms in mind. Liberal theories S P R I N G 1 9 9 8 43 International Relations identify the instruments that states can use to achieve shared inter- ests, highlight the powerful economic forces with which states and societies must now contend, and help us understand why states may differ in their basic preferences. Paradoxically, because U.S. protec- tion reduces the danger of regional rivalries and reinforces the "liber- al peace" that emerged after 1945, these factors may become relatively more important, as long as the United States continues to provide security and stability in many parts of the world. Meanwhile, constructivist theories are best suited to the analysis of how identities and interests can change over time, thereby producing

- 56. subtle shifts in the behavior of states and occasionally triggering far- reaching but unexpected shifts in international affairs. It matters if political identity in Europe continues to shift from the nation- state to more local regions or to a broader sense of European identity, just as it matters if nationalism is gradually supplanted by the sort of "civiliza- tional" affinities emphasized by Huntington. Realism has little to say about these prospects, and policymakers could be blind-sided by change if they ignore these possibilities entirely. In short, each of these competing perspectives captures important aspects of world politics. Our understanding would be impoverished were our thinking confined to only one of them. The "compleat diplo- mat" of the future should remain cognizant of realism's emphasis on the inescapable role of power, keep liberalism's awareness of domestic forces in mind, and occasionally reflect on constructivism's vision of change. W A N T T O K N O W M O R E ? For a fair-minded survey of the realist, liberal, and marxist paradigms, see Michael Doyle's Ways of War and Peace (New York, NY: Norton, 1997). A guide to some recent developments in international political

- 57. thought is Doyle & G. John Ikenberry, eds., New Th/nking in Inter. national Relations Theory (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1997). Those interested in realism should examine The Per//s of Anarchy: Contemporary Realism and International Security (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995) by Michael Brown, Sean Lynn-Jones, & Steven Miller, eds.; "Offensive Realism and Why States Expand Their War Aims" (Security Studies, Summer 1997) by Eric Labs; and "Dueling Realisms" (International Organization, Summer 1997) by Stephen Brooks. For alter- 44 F O R E I G N P o I . I C Y Walt native realist assessments of contemporary world politics, see John Mearsheimer's "Back to the Future: Instability in Europe after the Cold War" (International Secur/ty, Summer 1990) and Robert Jervis' " T h e Future of World Politics: Will I t Resemble the Past?" (Interna- t/ona/Secur/ty, Winter 1991-92). A realist explanation of ethnic con- flict is Barry Posen's " T h e Security Dilemma and Ethnic Conflict" (Survival, Spring 1993); an up-to-date survey of offense.defense

- 58. theory can be found in " T h e Security Dilemma Revisited" by Charles Glaser (World Politics, October 1997); and recent U.S. foreign policy is explained in Michael Mastanduno's "Preserving the Unipolar Moment: Realist Theories and U.S. Grand Strategy after the Cold War" (International Secur/ty, Spring 1997). The liberal approach to international affairs is summarized in Andrew Moravcsik's "Taking Preferences Seriously: A Liberal Theo- ry of International Politics" (International Organization, Autumn 1997). Many of the leading contributors to the debate on the democra- tic peace can be found in Brown & Lynn-Jones, eds., Debating the Democratic Peace (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996) and Miriam Elman, ed., Paths to Peace: Is Democracy the Answer? (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1997). The contributions of institutionalist theory and the debate on relative gains are summarized in David Baldwin, ed., Neo- realism and Neoliberalism: The Contemlxrra ~ Debate (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1993). A n important critique of the institutionalist literature is Mearsheimer's " T h e False Promise of Inter- national Institutions" (International Secur/ty, Winter 1994--95), but one should also examine the responses in the Summer 1995 issue.

- 59. For appli- cations of institutionalist theory to NATO, see John Duffield's "NATO's Functions after the Cold War" (Political Science L~arterly, Winter 1994-95) and Robert McCaUa's "NATO's Persistence after the Cold War" (International Organization, Summer 1996). Authors questioning the role of the state include Susan Strange in The Retreat of the State: The D / f ~ i o n of Power in the World Econ. omy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); and Jessica Math- ews in "Power Shift" (Foreign Affairs, January/February 1997). The emergence of the state is analyzed by Hendrik Spruyt in The Sovereign State and Its Com/mt/tors (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1994), and its continued importance is defended in Qlobal/z.at/on in Question: The International Economy and the Possibilities of Clover. nance (Cambridge: Polity, 1996) by Paul Hirst and Grahame Thomp- S P R I N G 1 9 9 8 45 International Affairs son, and Governing the Global Economy: International Finance and

- 60. the State (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994) by Ethan Kapstein. Another defense (from a somewhat unlikely source) is "The World Economy: The Future of the State" (The Economist, Septem- ber 20, 1997), and a more academic discussion of these issues is Peter Evans' "The Eclipse of the State? Reflections on Stateness in an Era of Globalization" (World Politics, October 1997). Readers interested in constructivist approaches should begin with Alexander Wendt's "Anarchy Is What States Make of It: The Social Construction of Power Politics" (International Organization, Spring 1992), while awaiting his Social Theory of International Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, forthcoming). A diverse array of cultural and constructivist approaches may also be found in Peter Katzenstein, ed., The Culture of National Security (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1996) and Yosef Lapid & Friedrich Kratochwil, eds., The Return of Culture and Identity in IR Theory (Boulder: CO" Lynne Rienner, 1996). For links to relevant Web sites, as well as a comprehensive index of related articles, access www.foreignpolicy.com. http ://www. foreign policy, com

- 61. S e l e c t e d full-text articles f r o m the current issue o f F O R E I G N P O L I C Y • A c c e s s to i n t e r n a t i o n a l data and r e s o u r c e s , O v e r 150 r e l a t e d W e b site links • I n t e r a c t i v e L e t t e r s to the E d i t o r , D e b a t e s , 10 y e a r s o f a r c h i v a l s u m m a r i e s and m o r e to come... A c c e s s the issues!