Sheet1TABLE 10-4REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN PUBLIC SCHOOL TEACHERS SA.docx

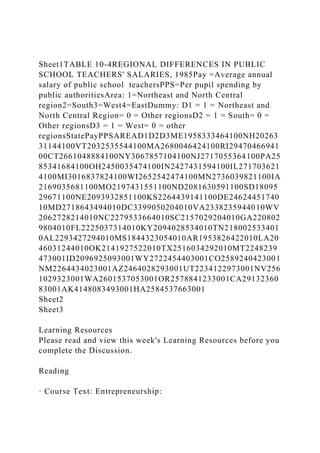

- 1. Sheet1TABLE 10-4REGIONAL DIFFERENCES IN PUBLIC SCHOOL TEACHERS' SALARIES, 1985Pay =Average annual salary of public school teachersPPS=Per pupil spending by public authoritiesArea: 1=Northeast and North Central region2=South3=West4=EastDummy: D1 = 1 = Northeast and North Central Region= 0 = Other regionsD2 = 1 = South= 0 = Other regionsD3 = 1 = West= 0 = other regionsStatePayPPSAREAD1D2D3ME1958333464100NH20263 31144100VT2032535544100MA2680046424100RI29470466941 00CT2661048884100NY3067857104100NJ2717055364100PA25 85341684100OH2450035474100IN2427431594100IL271703621 4100MI3016837824100WI2652542474100MN2736039821100IA 2169035681100MO2197431551100ND2081630591100SD18095 29671100NE2093932851100KS2264439141100DE24624451740 10MD2718643494010DC3399050204010VA2338235944010WV 2062728214010NC2279533664010SC2157029204010GA220802 9804010FL2225037314010KY2094028534010TN218002533401 0AL2293427294010MS1844323054010AR1953826422010LA20 46031244010OK2141927522010TX2516034292010MT2248239 473001ID2096925093001WY2722454403001CO2589240423001 NM2264434023001AZ2464028293001UT2234122973001NV256 1029323001WA2601537053001OR2578841233001CA29132360 83001AK4148083493001HA2584537663001 Sheet2 Sheet3 Learning Resources Please read and view this week's Learning Resources before you complete the Discussion. Reading · Course Text: Entrepreneurship:

- 2. Hisrich, R.D., Peters, M.P., & Shepherd, D.A. (2013). Entrepreneurship (Laureate Custom Education). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin. · Chapter 8, "The Marketing Plan" In this chapter, you will be introduced to the concept of developing a marketing plan. You will investigate the necessity of conducting research through industry and competitive analysis to effectively market the product being produced. You will follow the steps to preparing the marketing plan and generate ideas for creatively marketing a product. Focus on the definitions provided throughout the chapter. Review and think about the examples and anecdotes provided in the chapter that illustrate the major ideas being conveyed. Think about clever marketing strategies that have caught your attention in the past. What makes them stand out in your mind, and how could you generate this creativity for another venture? Chapter 9, "The Organizational Plan" In this chapter, you will learn about the importance of a strong management team when developing a new venture. Although the idea for a new venture may be held by one individual, preparing a team to launch the venture is necessary to its success. You will learn how the informal organizational plan is as important as the formal one. Finally, you will see how a board of directors or advisors can lend an objective eye and support a management team. Focus on the definitions provided throughout the chapter. Review and think about the examples and anecdotes provided in the chapter that illustrate the major ideas being conveyed. Consider your past experiences in working or playing with a team. Generally, are you more successful when working as a part of a team or individually?

- 3. Chapter 10, "The Financial Plan" In this chapter, you will examine the importance of creating budgets and generating accurate cash flow, and the sources and uses of fund statements. Balanced budgets can either make or break an organization. You will learn how positive profits can lead to negative cash flow as you investigate solutions to this type of situation. When studying the financial viability of an organization, you must look at the break-even point to decide cost values for the product. Lastly, you will look at software packages that can ease the stress of creating the necessary financial documents. Focus on the definitions provided throughout the chapter. Review and think about the examples and anecdotes provided in the chapter that illustrate the major ideas being conveyed. Consider your own financial budget or need for one. How does this budget drive your spending and saving habits? References Hisrich, R.D., Peters, M.P., & Shepherd, D.A. (2013). Entrepreneurship (Laureate Custom Education). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin. Custom Create Edition LAUREATE EDUCATI ON INC

- 4. 290 I '""'"""'""h;, -l-------- -- - THE FINANCIAL PLAN 1 To understand the role of budgets in preparing pro forma statements. 2 To understand why positive profits can still result in a negative cash flow. 3 To learn how to prepare monthly pro forma cash flow, income, balance sheet, and sources and applications of funds statements for the first year of operation. 4 To explain the application and calculation of the break-even point for the new venture. 5 To illustrate the alternative software packages that can be used for preparing financial statements. I Entrepreneurship, Eighth Edition I 291

- 5. ~----------------------------------r---·--~~~-~ OPENING PROFILE TONY HSIEH Not too many entrepreneurs have the goal of reaching a billion dollars in sales . At the age of 35, Tony Hsieh (pronounced "Shay") has reached this goal as the CEO and en- trepreneurial brain behind Zappos.com. His serious entrepreneurial endeavors began after graduation from Harvard University at the age of 23. He and classmate Sanjay Madan saw opportunities for advertisers who wanted to con- solidate large ad buys into a single package and subsequently launched LinkExchange in the early 1990s. LinkExchange of- fered small sites free advertising on a 2-to-1 basis. What this meant was that for every two ads a member displayed on their site, they would be granted one free ad on another member's site. The excess ad credits not used were then sold by LinkExchange to nonmembers, resulting in a substantial revenue stream. After getting investment capital in 1997, the company was seen as a

- 6. serious player in the Inter- net advertising market and was subsequently purchased by Microsoft for $265 million in 1998. After this success Tony co-founded Venture Frogs, which invested in Internet start- ups such as Ask Jeeves, Tellme Networks, and Zappos.com. In 1999, as an investor he be- gan to look more seriously at the long-term potential of Zappos.com. Initially, he was an advisor and consultant to Zappos.com, but eventually he joined the company full time in 2000 as co-CEO. He later took over the reins completely and moved the operation to Las Vegas because of the lower real estate rates and abundance of call-center workers. Under his leadership the company grew from $1.6 million in sales in 2000 to more than $1 billion in sales in 2008. In fact the company doubled its sales every year from 1999 to 2008. Tony realized when he joined Zappos.com that the Internet had not become a major player as a shopping choice for consumers. He discovered that the footwear industry, at $40 billion per year, was mostly a result of retail store sales

- 7. and that only 5 percent of the sales came from mail-order catalogs. He saw this as a huge opportunity for the company, particularly since he believed that the Web would surpass mail-order busi- ness as a percentage of total sales. Thus, he saw 5 percent of $40 billion as a reason- able goal for his business. Tony's business model was unique and to some retailers costly, yet it has been ex- tremely successful. Part of Hsieh's approach is to focus on customer service. Zappos offers free shipping, fast delivery, and a 365-day return policy. He even relocated his 281 292 I ,, •.• ~"'""h'' ·~---------- ------------ ·-·- -------~- -------- ·-- --- 282 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN warehouse to Kentucky to be nearer the UPS hub and to ensure the fast delivery of me products offered, which has recently expanded to clothing, handbags, and accessories

- 8. The company's focus on customer service is designed to make sure the customer has 2 quality experience from beginning to end. In addition, all employees once hired mus-: complete a four-week customer loyalty training program to make sure they unde·- stand the culture that has made the company so successful. To ensure that the hires are serious, Tony makes a visit during the second week and offers anyone $2,000 if t he would like to drop out and quit the program. Only 1 percent of the hires have ta ke him up on the offer. The unique culture of the company also includes such things as happy hours, a nap room, fully paid health insurance, and life- related issue support that Tony pays for out of his own pocket. His philosophy regarding these strategies is that only a happy employee can provide great service. Once Zappos wins over a customer (75 percent of the customers are repeaters), t he company tries to ensure their continued interest by keeping them engaged in vario us

- 9. online and social media outlets. Customers are invited to submit reviews and to sha re their experience with others. This not on ly enhances each customer's loyalty but also attracts new customers. Although these services, both at the employee and customer level, are costly to t he company, Tony believes that they are crucial in maintaining a competitive edge an d were important in achieving the $1 billion in sales. Good budgeting and financial plan- ning are also significant factors in helping to reach these lofty goals. 1 The financial plan provides the entrepreneur with a complete picture of how much and when funds are coming into the organization, where funds are going, how much cash is avail- able, and the projected financial position of the firm. It provides the short-term basis for bud- geting control and helps prevent one of the most common problems for new ventures-lack of cash. We can see from the preceding example how important it is to understand the role of the financial plan. Without careful financial planning, especially in light of the costly customer services, Zappos.com could have suffered serious cash flow problems. The financial plan must explain to any potential investor how the entrepreneur plans to meet all financial obliga-

- 10. tions and maintain the venture's liquidity in order to either pay off debt or provide a good re- turn on investment. In general, the financial plan will need three years of projected financial data to satisfy any outside investors. The first year should reflect monthly data. This chapter discusses each of the major financial items that should be included in the fi- nancial plan: pro forma income statements, pro forma cash flow, pro forma balance sheets, and break-even analysis. As we saw in the Zappos.com example, Internet start-ups have some unique financial characteristics, which are included in the discussion that follows. OPERATING AND CAPITAL BUDGETS Before developing the pro forma income statement, the entrepreneur should prepare oper- ating and capital budgets. If the entrepreneur is a sole proprietor, then he or she is respon- sible for the budgeting decisions . In the case of a partnership, or where employees exist, the '""''""'""h;p, Eighth Editioo I 293 -- ---------- ----------- --- -- --- ··------·- --- ----------+----~ CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 283 initial budgeting process may begin with one of these individuals, depending on his or her role in the venture. For example, a sales budget may be prepared by a sales manager, a manufacturing budget by the production manager, and so on.

- 11. Final determination of these budgets will ultimately rest with the owners or entrepreneurs. As can be seen in the following, in the preparation of the pro forma income statement, the entrepreneur must first develop a sales budget that is an estimate of the expected volume of sales by month. Methods of projecting sales are discussed next. From the sales forecasts the entrepreneur will then determine the cost of these sales. In a manufacturing venture the entrepreneur could compare the costs of producing these internally or subcontracting them to another manufacturer. Also included will be the estimated ending inventory needed as a buffer against possible fluctuations in demand and the costs of direct labor and materials. Table 10.1 illustrates a simple format for a production or manufacturing budget for the first three months of operation. This provides an important basis for projecting cash flows for the cost of goods produced, which includes units in inventory. The important informa- tion from this budget is the actual production required each month and the inventory that is necessary to allow for sudden changes in demand. As can be seen, the production required in the month of January is greater than the projected sales because of the need to retain l 00 units in inventory. In February the actual production will take into consideration the in- ventory from January as well as the desired number of units needed in inventory for that month. This continues for each month, with inventory needs likely increasing as sales in-

- 12. crease. Thus, this budget reflects seasonal demand or marketing programs that can increase demand and inventory. The pro forma income statement will only reflect the actual cost of goods sold as a direct expense. Thus, in those ventures in which high levels of inventory are necessary or where demand fluctuates significantly because of seasonality, this budget can be a very valuable tool to assess cash needs. After completing the sales budget, the entrepreneur can then focus on operating costs. First a list of fixed expenses (incurred regardless of sales volume) such as rent, utilities, salaries, ad- vertising, depreciation, and insurance should be completed. Estimated costs for many of these items can be ascertained from personal experience or industry benchmarks, or through direct contact with real estate brokers, insurance agents, and consultants. Industry benchmarks for preparing financial pro forma statements were discussed in the financial plan section of Chapter 7 (see Table 7.2 for a list of financial benchmark sources). Anticipation of the addition of space, new employees, and increased advertising can also be inserted in these projections as deemed appropriate. These variable expenses must be linked to strategy in the business plan. Table 10.2 provides an example of an operating budget. In this example, we can see that salaries increase in month 3 because of the addition of a shipper, advertising increases because the primary season for this product is approaching, and payroll taxes increase because of the additional employee. This budget, along with the manufacturing budget illustrated in

- 13. Table 10.1, provides the basis for the pro forma statements discussed in this chapter. TABLE 10.1 A Sample Manufacturing Budget for First Three Months Jan. Feb. Mar. Projected sales {units) 5,000 8,000 12,000 Desired ending inventory 100 200 300 Available for sale 5,100 8,200 12,300 Less: beginning inventory 0 100 200 Total production required 5,100 8,100 12, 100 294 I '"'~'~"'""";' ·--~-· ~----- ---- ·-- --·--·-- ·--· - ---··----------- ----- --------··--·· - --------·---- - ------- $ ETHICS ARE YOU A GOOD LEADER? You will be if you draw on key ethical princip les. Here's how to do it, whether you're a CEO, a banker, an entrepreneur, or anyone else in business. I propose the following leadership guidelines for C-level executives, investment bankers, entrepreneurs, and everyone else whose decisions can affect the financial well being of other people.

- 14. 1. What's Good for the Gander Is Good for the Goose. At a time when companies are slashing their la- bor forces and freezing salary increases, and when some employees are being asked to take lower-paying positions, it is deeply unethica l for leaders to retain their sky-high compensation and to expect enormous bonuses. 2. Know Your Product. According to a recent three-part story in The Wall Street Journal, the willingness of investors to buy and sell financial products whose com- plexity they didn't fully understand was one of the primary catalysts of the bust. Because money was being made in these deals, no one thought to question what was going on or had the strength of character to speak up about any suspicions. However, knowing your product isn't a nicety of doing business. It is an ethical obligation-to your company, your clients, and yourself. 3. Winning [at All Costs) Is for Losers. Most of us were taught that we should treat peo- ple the way we'd like to be treated ourselves. However, too many business leaders have failed to take this seriously. Instead, the guideline see ms to be, "Get all you can by any means necessary." 4. Tell the Truth.

- 15. A leader has an ethical obligation to be honest with stakeholders about issues that directly con- cern them. 5. Prevent Harm. When you can reasonably foresee that a deci- sion is likely to hurt people and you make that decision anyway, you're being both irrespon- sible and stupid . For example, subprime mortgage lenders and brokers who lend money to people likely to default are enriching them- selves at the expense of the rest of us, since the federal government may be called upon for financial rescue. 6 . Don't Ex ploit. It is easy to take advantage of a situation for financial gain, but doing so isn't consistent with I TABLE 10.2 A Sample Operating Budget for Fi rst Th ree Months ($000s) 284 Expense Salaries Rent Utilities Advertising

- 16. Selling expenses Insurance Payroll taxes Depreciation Office expenses Tot al expenses Jan. $23.2 2 0.9 13.5 1 2 2.1 1.2 1.5 $47.4 Feb. Mar.

- 17. $23.2 $26.2 2 2 0.9 0.9 13.5 17 2 2 2.1 2.5 1.2 1.2 ~ 1.5 $47.4 $54.3 good leadership. After Hurricane Ike hit last year, the wholesale price of gasoline shot up, which was nothing more than price gouging. In the short run, companies that exploited a nat- ural tragedy may have profited financially, but the long-term negative consequences are real and significant: In New York State, for example, more than a dozen companies were fined more than $60,000 for unfair business practices fol- lowing Hurricane Katrina. 7. Don't Make Promises You Can't Keep ... ... and keep the promises you make. There are

- 18. rare circumstances in which we not only have a right but an ethical obligation to break a prom- ise, but generally speaking, we have a strong duty to be true to our word. 8. Take Responsibility for Your Mistakes. Transparency and accountability should be the new buzzwords. This means, in part, that busi- ness leaders who make mistakes should apolo- gize to those they have let down and do what- ever is necessary to make amends. In the wake of the toy industry's lead-paint scare in 2007, Mattei CEO Robert Eckert took the high road and told a Senate subcommittee that the com- pany failed "by not closely overseeing subcon- tractors in China whose toys didn't meet U.S. safety standards," and that Mattei was working with the Consumer Product Safety Entrepreneurship, Eighth Edition 295 Commission to ensure that these products would be safer. 9. People, Not Profits. Money has no intrinsic value; it is good only for what it can get us. For the good leader, this means that the ultimate goal in business-and life-is not hoarding riches but making things better for all, especially the neediest. 10. Be Kind, Not King. The relentless quest to be No.1 can blind us to

- 19. what's really valuable in life: being a decent hu- man being. Yes, good leaders are enthusiasti- cally devoted to accomplishing their mission, but this pursuit cannot be at the expense of the well being of others. It should be obvious by now that the above rules apply not just to those in the financial sector but to everyone else, too. They are, after all, based on the five fundamental principles of ethics: Do No Harm, Make Things Better, Respect Others, Be Fair, and Be Loving. As Peter Drucker pointed out, it is not enough to do things right; we must also do the right things. The good leader today is concerned not only with get- ting from A to B, but with deciding whether B is worth getting to in the first place. Source: Reprinted from February 2, 2009 issue of Business Week by special permission, copyright © 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Compa- nies, Inc., "Are You a Good Leader?" by Bruce Weinstein, Business Week Online, p. 13. Capital budgets are intended to provide a basis for evaluating expenditures that will impact the business for more than one year. For example, a capital budget may project expenditures for new equipment, vehicles, computers, or even a new facility. It may also consider evaluating the costs of make or buy decisions in manufacturing or a comparison of leasing, buying used, or buying new equipment. Because of the complexity of these decisions, which can include the computation of the cost of capital and the anticipated

- 20. return on the investment using present value methods, it is recommended that the entrepre- neur enlist the assistance of an accountant. PRO FORMA INCOME STATEMENTS The marketing plan discussed in Chapter 8 provides an estimate of sales for the next 12 months. Since sales are the major source of revenue and since other operational activi- ties and expenses relate to sales volume, it is usually the first item that must be defined. Table 10.3 summarizes all the profit data during the first year of operations for MPP Plastics. This company makes plastic moldings for such customers as hard goods 285 296 I Eo<repreooo•h;p --------t--------- ···-· ---- ·-------------·- ·-----·-- ·------------ ----------------.,jH 286 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN TABLE 10.3 MPP Plastics Inc., Pro Forma Income Statement, First Year by Month ($000s) Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. Totals Sales 20.0 32.0 48.0 70.0 90.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 80.0 80.0 120.0 130.0 970.0

- 21. Less: Cost of goods sold 10.0 16.0 24.0 35.0 45.0 50.0 50.0 50.0 40.0 40.0 60.0 65.0 485.0 Gross profit 10.0 16.0 24.0 35.0 45.0 50.0 50.0 50.0 40.0 40.0 60.0 65.0 485.0 Operating expenses Salaries* 23.2 23.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 308.4 Rent 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 24.0 Utilities 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.8 0.8 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.8 0.9 10.3 Advertising 13.5 13.5 17.0 17.0 17.0 17.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 21.ot 17.0 17.0 192.0 Sales expenses 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 12.0 Insurance 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 24.0 Payroll taxes 2.1 2.1 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 29.2 Depreciation* 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 1.2 14.4 Office expenses ~ 1.5 1.5 1.7 1& 2.0 2.0 2.0 1& 1& 2.2 2.2 22.0 Total operating expenses 47.4 47.4 54.3 54.4 54.5 54.7 51.8 51.8 51.6 58.5 54.9 55.0 636.3 Gross profit (37.4) (31.4) (30.3) (19.4) (9.5) (4.7) (1.8) (1 .8)

- 22. (11.6) (18.5) 5.1 10.0 (151.3) *Added shipper in month 3. tTrade show *Plant and equipment of $72,000 depreciated straight line for five years. pro forma income Projected net profit calculated from projected revenue minus projected costs and expenses manufacturers, toy manufacturers, and appliance manufacturers. As can be seen from the pro forma income statement in Table 10.3, the company begins to earn a profit in the eleventh month. Cost of goods sold remains consistent at 50 percent of sales revenue. In preparation of the pro forma income statement, sales by month must be calculated first. Marketing research, industry sales, and some trial experience might provide the basis for these figures. Forecasting techniques such as survey of buyers' intentions, composite of sales force opinions, expert opinions, or time series may be used to project sales.Z It may also be possible to find financial data on similar start-ups to assist with these projections . As would be expected, it will take a while for any new venture

- 23. to build up sales. The costs for achieving these increases can be disproportionately higher in some months, depending on the given situation in any particular period. Sales revenue for an Internet start-up is often more difficult to project since extensive advertising will be necessary to attract customers to the Web site. For example, a giftware Internet company can anticipate no sales in the first few months until awareness of the Web site has been created. Heavy advertising expenditures (discussed subsequently) also will be incurred to create this awareness. Given existing data on the number of "hits" by a similar type of Web site, a giftware Internet start-up could project the number of average hits ex- pected per day or month. From the number of hits, it is possible to project the number of consumers who will actually buy products from the Web site and the average dollar amount per transaction. Using a reasonable percentage of these "hits" times the average transaction will provide an estimate of sales revenue for the Internet start- up. The pro forma income statements also provide projections of all operating expenses for each of the months during the first year. As discussed earlier and illustrated in Table 10.2, '""'P~"'""hip, Hghth Edttloo I 297 - ---------·------·----·--- ----------- -----·---------------~---~--

- 24. CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 287 each of the expenses should be listed and carefully assessed to make sure that any increases in expenses are added in the appropriate month. 3 For example, selling expenses such as travel, commissions, and entertainment should be expected to increase somewhat as terri- tories are expanded and as new salespeople or representatives are hired by the firm. Selling expenses as a percentage of sales also may be expected to be higher initially since more sales calls will have to be made to generate each sale, particularly when the firm is an un- known. The cost of goods sold expense can be determined either by directly computing the variable cost of producing a unit times the number of units sold or by using an industry standard percentage of sales. For example, for a restaurant, the National Restaurant Asso- ciation or Food Marketing Institute publishes standard cost of goods as a percentage of sales. These percentages are determined from members and studies completed on the restaurant industry. Other industries also publish standard cost ratios, which can be found in sources such as those listed in Table 7 .2 . Trade associations and trade magazines will also often quote these ratios in industry newsletters or trade articles . Salaries and wages for the company should reflect the number of personnel employed as well as their role in the organization (see the organization plan in Chapter 9) . As new personnel are hired to support the increased business, the costs will need to be included

- 25. in the pro forma statement. In March, for example, a shipper is added to the staff. Other increases in salaries and wages may also reflect raises in salary. The entrepreneur should also consider increasing selling expenses as sales increase, ad- justing taxes because of the addition of new personnel or raises in salary, increasing office expenses relative to the increase in sales, and modifying the advertising budget as a result of seasonality or simply because in the early months of start-up the budget may need to be higher to increase visibility. These adjustments actually occur in our MPP Plastics example (Table 10.3) and are reflected in the month-by-month pro forma income statement for year 1. Any noteworthy changes that are made in the pro forma income statement are also labeled, with explanations provided. In addition to the monthly pro forma income statement for the first year, projections should be made for years 2 and 3. Generally, investors prefer to see three years of income projections . Year 1 totals have already been calculated in Table 10.3 . Table 10.4 illustrates the yearly totals of income statement items for each of the three years. Calculation of the percent of sales of each of the expense items for year 1 can be used by the entrepreneur as a guide for determining projected sales and expenses for year 2; those percentages then can be considered in making the projections for year 3. In addition, the calculation of percent of sales for each year is useful as a means of financial control so that the entrepreneur can

- 26. ascertain whether any costs are too high relative to sales revenue. In year 3, the firm expects to significantly increase its profits as compared with the frrst and second years. In some in- stances, the entrepreneur may find that the new venture does not begin to earn a profit un- til sometime in year 2 or 3. This often depends on the nature of the business and start-up costs. For example, a service-oriented business may take less time to reach a profitable stage than a high-tech company or one that requires a large investment in capital goods and equipment, which will take longer to recover. In the pro forma statements for MPP Plastics (Tables 10.3 and 10.4), we can see that the venture begins to earn a profit in the eleventh month of year 1. In the second year, the company does not need to spend as much money on advertising and, with the sales increase, shows a modest profit of $16,300. However, in year 3 we see that the venture adds an additional em- ployee and also incurs a 26 percent increase in sales, resulting in a net profit of$127,900. In projecting the operating expenses for years 2 and 3, it is helpful to frrst look at those expenses that will likely remain stable over time. Items like depreciation, utilities, rent, in- surance, and interest are likely to remain steady unless new equipment or additional space is purchased. Some utility expenses such as heat and power can be computed by using

- 27. I 298 j Entrepreneurship ~------~-..:..~.--,-·-~-- ----- ---- - - - ------ ----·-- ----- --- -··---·- -------·-·----·---···---·-·---·-··--·-··-···------··----·-· ------ 11 288 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN TABLE 10.4 MPP Plastics Inc., Pro Forma Income Statement, Three-Year I Summary ($000s) Percent Year 1 Percent Year 2 Percent Year 3 Sales 100.0 970 .0 100.0 1,264.0 100.0 1,596.0 Less: Cost of goods sold 50.0 485 .0 50.0 632.0 50.0 798.0 Gross profit 50.0 485.0 50.0 632.0 50.0 798.0 Operating expenses Salaries 31.8 308.4 24.4 308.4 21.8 348.4 Rent 2.5 24.0 1.9 24.0 1.5 24.0 Utilities 1.1 10.3 0.8 10.3 0.7 10.3 Advertising 19.8 192.0 13.5 170.0 11.3 180.0 Sales expenses 1.2 12.0 1.0 12.5 0.8 13.5 Insurance 2.4 24.0 1.9 24.0 1.5 24.0 Payroll & misc. taxes 3.0 29.2 2.3 29.2 2.0 32.0

- 28. Depreciat ion 1.5 14.4 1.1 14.4 0.9 14.4 Office expenses 2.3 22.0 ___1.,§ ___112 _1.2 ~ Total operating expenses 65.6 636.3 48 .7 615.3 42 .0 670.1 Gross profit (loss) (15.6) (151.3) 1.3 16.3* 8.0 127.9* Taxes 0.0 __Q,Q .......QJ1 _____Q,.Q .......QJ1 0.0 Net profit (15.6) (151.3) 1.3 16.3 8.0 127.9 *No taxes are incurred in profitable years 2 and 3 because of the carryover of losses in year 1. industry standard costs per square foot of space that is utilized by the new venture. Selling expenses, advertising, salaries and wages, and taxes may be represented as a percentage of the projected net sales. When calculating the projected operating expenses, it is most im- portant to be conservative for initial planning purposes. A reasonable profit that is earned with conservative estimates lends credibility to the potential success of the new venture. For the Internet start-up, capital budgeting and operating expenses will tend to be consumed by equipment purchasing or leasing, inventory, and advertising expenses. For example, the gift- ware Internet company introduced earlier would need to purchase or lease an extensive amount of computer equipment to accommodate the potential buyers from the Web site. Inventory costs would be based on the projected sales revenue just as would be the case for any retail

- 29. store. Advertising costs, however, would need to be extensive to create awareness for the gift- ware Web site. These expenses would typically involve a selection of search engines such as Yahoo!, Lycos, MSN, and Google; links from the Web sites of magazines such as Woman 's Day, Family Circle, and Better Homes and Gardens; and extensive media advertising in maga- zines, television, radio, and print-all selected because of their link to the target market. PRO FORMA CASH FLOW Cash flow is not the same as profit. Profit is the result of subtracting expenses from sales , whereas cash flow results from the difference between actual cash receipts and cash pay- ments. Cash flows only when actual payments are received or made. Sales may not be re- garded as cash because a sale may be incurred but payment may not be made for 30 days. In I I Entrepreneurship, Eighth Edition I 299 - - --·· ··--·--·- ---·- ---------,-- -- CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 289 addition, not all bills are paid immediately. On the other hand, cash payments to reduce the principal on a loan do not constitute a business expense but do constitute a reduction of cash.

- 30. Also, depreciation on capital assets is an expense, which reduces profits, not a cash outlay. For an Internet start-up such as our giftware company discussed earlier, the sales trans- action would involve the use of a credit card in which a percentage of the sale would be paid as a fee to the credit card company. This is usually between 1 and 3 percent depend- ing on the credit card. Thus, for each sale only 97 to 99 percent of the revenue would be net revenue because of this fee. As stated at the beginning of this chapter, one of the major problems that new ventures face is cash flow. On many occasions, profitable firms fail because of lack of cash. Thus, using profit as a measure of success for a new venture may be deceiving if there is a signif- icant negative cash flow. For strict accounting purposes there are two standard methods used to project cash flow, the indirect and the direct method. The most popular of these is the indirect method, which is illustrated in Table 10.5. In this method the objective is not to repeat what is in the in- come statement but to understand there are some adjustments that need to be made to the net income based on the fact that actual cash may or may not have actually been received or disbursed. For example, a sales transaction of $1,000 may be included in net income, but if the amount has not yet been paid, no cash has been received. Thus, for cash flow pur- poses there is no cash available from the sales transaction. For

- 31. simplification and internal monitoring of cash flow purposes, many entrepreneurs prefer a simple determination of cash in less cash out. This method provides a fast indication of the cash position of the new venture at a point in time and is sometimes easier to understand. It is important for the entrepreneur to make monthly projections of cash like the monthly projections made for profits. The numbers in the cash flow projections are constituted from TABLE 10.5 Statement of Cash Flows: The Indirect Method Cash Flow from Operating Activities ( + or - Reflects Addition or Subtraction from Net Income) Net income Adjustments to net income: Noncash nonoperating items + depreciation and amortization Cash provided by changes in current assets or liabilities: Increase(+) or decrease(-) in accounts receivable Increase(+) or decrease(-) in inventory Increase(+) or decrease(-) in prepaid expenses Increase(+) or decrease(-) in accounts payable et cash provided by operating activities

- 32. cash Flow from Other Activities Capital expenditures(-) Payments of debt (-) Dividends paid (-) Sale of stock(+) et cash provided by other activities crease (Decrease) in Cash XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XX, XXX (XXX) (XXX) (XXX) XXX

- 33. (XXX) XXX I 300 I Entrepreneurship ------·-.... -'-"-"··---- ·r· --- -~--- - ----- - ---------- -~-------- ---- ·- --- ------- ------- -------------·-- -------·- - --- -- --~-.,--- -- ----- ---- AS SEEN IN BUSINESSWEEK PROVIDE ADVICE TO AN ENTREPRENEUR ABOUT SOLVING THEIR CASH-FLOW PROBLEM TO STAY IN BUSINESS Hot & Cold Inc., a plumbing and heating supply com- pany in the heart of Virginia's Shenandoah Valley, is headed for the slaughterhouse. As the housing boom grew, so did sales, from $7 million a year to $14 mil- lion over four years. But as the company expanded, its problems multiplied, and no amount of sales could cover the warts. As the economy faltered and poor management continued, revenue started dropping by more than $2 million a year. Crunching the numbers over the past five years shows lost opportunity and bad financial manage- ment have cost the company about $5 million in prof- its. Overtime alone is about $250,000 a year. Today Hot & Cold is at $6 million in sales and is running at a loss in excess of $1 million . The bank is nervous, and ready to pull the plug on its line of credit. The steady supply of new business has dried up, and the three

- 34. owners' lives are on the line. The old cash cow is chopped meat. To keep the company alive, they've mortgaged their homes, maxed out their credit cards at usurious interest rates, and cashed in their 401 (k)s. Worker morale is low, and employees are phoning it in because they are convinced they'll be out of a job tomorrow. As a result, the few remaining clients are unhappy, and threaten- ing to take their business elsewhere. SOLUTION: CONTROL, CONTROL, CONTROL The owners of Hot & Cold have three choices: Walk away at great personal financial ruin; hope for a big client to fly to their rescue and help them pay off their huge debt; or take control of their own busi- ness. They're teetering on the verge of bankruptcy, but it's not too late. The three guys who took over from the family who founded Hot & Cold have no training as man- agers. These are hard-working, talented contractors and engineers with great knowledge of how to carry plumbing and installation projects to completion. But, for most of their careers, they worked for some- body else. First they need to sit down with each departmen head and develop an adopting plan for cash manage- ment. They need to be clear in their instructions, and forceful in their insistence that there will be dire con- sequences for failure to comply. Hold departme n meetings at 8 a.m. on Monday, issue marching orde rs, then meet again on Friday at 6 p.m. to see what did

- 35. and did not get done. Every job needs to be moni- tored by microscope from start to finish. It'll hurt. Hot & Cold requires drastic internal over- haul, including deep cuts in operating costs. They can't be "tepid" about this. At least 20% of thei r workforce of 50 will have to be fired. This business needs to get serious about collecting the cash that clients owe them, even if they have to take a hit by offering cash discounts or accepting partial payment just to bring the money in. I also recommend that they meet face to face with their banker. If they've followed my advice so fa r, they will be able to point to the cost measures al- ready in place and forestall foreclosure on their loan. * ADVICE TO AN ENTREPRENEUR An entrepreneur friend saw the above article and has asked you for some advice: 1. My receivables are averaging about 75 days. Should I be concerned that this will affect my cash flow? 2. What can I do to get faster payments on my billing? 3. My business is profitable, but I seem to always run short of cash at the end of each month? Why is that? *Source: Reprinted from July 24, 2009 issue of Business Week by special permission, copyright© 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Compa-

- 36. nies, Inc., www.businessweek.com, "Solve Your Cash-Flow Problem to Stay in Business," by George Cloutier with Samantha Marshall. the pro forma income statement with modifications made to account for the expected tim- ing of the changes in cash. If disbursements are greater than receipts in any time period, the entrepreneur must either borrow funds or have cash in a bank account to cover the higher disbursements. Large positive cash flows in any time period may need to be invested in short-term sources or deposited in a bank to cover future time periods when disbursements 290 I -·-----~----~---------------- ------------------------------------ _ :""''''"'"''""': E;ghth_E<J;tlo"_ t _;3_0 1 __ pro forma cash flow Projected cash available calculated from projected cash accumulations minus projected cash disbursements

- 37. CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 291 are greater than receipts. Usually the ftrst few months of the start-up will require external cash (debt) to cover the cash outlays. As the business succeeds and cash receipts accumu- late, the entrepreneur can support negative cash periods. Table 10.6 illustrates the pro forma cash flow over the fust 12 months for MPP Plastics. As can be seen, there is a negative cash flow based on receipts less disbursements for the fust 11 months of operation. The likelihood of incurring negative cash flows is very high for any new venture, but the amount and length of time before cash flows become positive will vary, depending on the nature of the business. In Chapter 13 we discuss how the entrepreneur can manage cash flow in the early years of a new venture. For this chapter, we will focus on how to project cash flow before the venture is launched. The most difficult problem with projecting cash flows is determining the exact monthly receipts and disbursements. Some assumptions are necessary and should be conservative so that enough funds can be maintained to cover the negative cash months. In this fum, it is antic- ipated that 60 percent of each month's sales will be received in cash with the remaining 40 per- cent paid in the subsequent month. Thus, in February we can see that the cash receipts from sales totaled $27,200. This resulted from cash sales in February of 60 percent of $32,000, or $19,200, plus the 40 percent of sales that occurred in January

- 38. (.40 X $20,000 = $8,000) but was not paid until February, thus resulting in the total cash received in February of $27,200. This process continues throughout the remaining months in year 1. Similar assumptions are made for the cost of goods disbursement. It is assumed in our example that 80 percent of the cost of goods is paid in the month that it is incurred, with the TABLE 10.6 MPP Plastics Inc., Pro Forma Cash Flow, First Year by Month ($000s) Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May June July Aug. Sept. Oct. Nov. Dec. Receipts Sales 12.0 27.2 41.6 61.2 82.0 96.0 100.0 100.0 88.0 80.0 104.0 126.0 Disbursements Equipment purchase 72.0 Cost of goods 8.0 14.8 22.4 37.6 43.0 49.0 50.0 50.0 42.0 40.0 56.0 60.0 Salaries 23.2 23.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 26.2 Rent 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 Utilities 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.8 0.8 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.8 0.9 Advertising 13.5 13.5 17.0 17.0 17.0 17.0 14.0 14.0 14.0 21.0

- 39. 17.0 17.0 Sales expense 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 Insurance 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 2.0 Payroll & misc. taxes 2.1 2.1 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 Office expenses 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.7 1.8 2.0 2.0 2.0 1.8 1.8 2.2 2.2 Inventory* 0.2 0.4 0.6 ____li 0.8 0.8 1.0 ____1Q 1.0 1.0 ____11 1.2 Total disbursements 126.4 61.4 76.1 91.4 97.1 103.3 101.6 101.6 93.4 98.3 110.9 115.0 Cash flow (114.4} (34.2) (34.5) (30.2) (15.1) (7.3) (1.6) (1.6) (5.4) (18.3) (6.9} 11.0 Beginning balancet 300.0 185.6 151 .4 116.9 86.7 71.6 64.3 62.7 61.1 55.7 37.4 30.5 Ending balance 185.6 151.4 116.9 86.7 71.6 64.3 62.7 61.1 55.7 37.4 30.5 41.5 *Inventory is valued at cost or average of $2.00/unit. tTirree founders put up $!00,000 each for working capital through the first three years. After the third year the venture will need debt or equity financing for expansion. 302 I '"'"P""'""h;p --- --------+ ---- -- -------- ----··--- -- -·- -----

- 40. 292 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN pro forma balance sheet Summarizes the projected assets , liabilities, and net worth of the new venture assets Items that are owned or available to be used in the venture operations remainder paid in the following month. Thus, referring back to Table 10.3, we can note that in February the actual cost of goods was $16,000. However, we actually pay only 80 percen· of this in the month incurred-but we also pay 20 percent of the cost of goods sold thar is still due from January. Thus, the actual cost of goods cash outflow in February is .8 X $16,000 + .2 X $10,000, or a total of $14,800. Using conservative estimates, cash flows can be determined for each month. These cash flow projections assist the entrepreneur in determining how much money he or she will need to raise to meet the cash demands of the venture. In our example, the venture stans

- 41. with a total of $300,000, or $100,000 from each of the three founders. We can see that by the twelfth month, the venture begins to turn a positive cash flow from operations, still leaving enough cash available ($41,500) should the projections fall short of expectations . If the entrepreneurs in our example had to use debt for the start- up, then they would need to show the interest payments in the income statement as an operating expense and indicate the principal payments to the bank as a cash disbursement, not as an operating expense. This issue often creates cash flow problems for entrepreneurs when they do not realize thar debt is a cash disbursement only and that interest is an operating expense. It is most important for the entrepreneur to remember that the pro forma cash flow, like the income statement, is based on best estimates. A start-up venture in a weak economy may find it necessary to revise cash flow projections frequently to ensure that their accu- racy will protect the firm from any impending disaster. The estimates or projections should include any assumptions so that potential investors will understand how and from where the numbers were generated.4 In the case of both the pro forma income statement and the pro forma cash flow, it is sometimes useful to provide several scenarios, each based on different levels of success of the business. These scenarios and projections not only serve the purpose of generating pro forma income and cash flow statements but, more importantly,

- 42. familiarize the entrepreneur with the factors affecting the operations . PRO FORMA BALANCE SHEET The entrepreneur should also prepare a projected balance sheet depicting the condition of tlre /Ju:tirress at t.he end of the frrst year. The balance sheet wiU require the use of the pro forma income and cash flow statements to help justify some of the figures. 5 The pro forma balance sheet reflects the position of the business at the end of the first year. It summarizes the assets, liabilities, and net worth of the entrepreneurs. Every business transaction affects the balance sheet, but because of the time and expense, as well as need, it is common to prepare balance sheets at periodic intervals (i.e. , quarterly or annually). Thus, the balance sheet is a picture of the business at a certain moment in time and does not cover a period of time. Table 10.7 depicts the balance sheet for MPP Plastics. As can be seen, the total assets equal the sum of the liabilities and owners ' equity. Each of the categories is explained here: • Assets. These represent everything of value that is owned by the business. Value is not necessarily meant to imply the cost of replacement or what its market value would be but is the actual cost or amount expended for the asset. The assets are categorized as current or fixed. Current assets include cash and anything

- 43. else that is expected to be converted into cash or consumed in the operation of the business during a period of one year or less. Fixed assets are those that are tangible and will be used over a long period of time . These current assets are often dominated by receivables or money that is owed to the new venture from customers. Management of these receivables is Entrepreneurship, Eighth Edition 303 CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 293 TABLE 10.7 MPP Plastics Inc., Pro Forma Balance Sheet, End of First Year ($000s) Assets Current assets Cash $41.5 Accounts receivable 52.0 Inventory 1.2 Total current assets $ 94.7 Fixed assets Equipment 72.0

- 44. Less depreciation 14.4 Total fixed assets 57.6 Total assets $152.3 Liabilities and Owners' Equity Current liabilities Accounts payable $13.0 Total liabilities $ 13.6 Owners' equity K. Peters 100.0 C. Peters 100.0 J. Welch 100.0 Retained earnings (160.7) Total owners' equity 148.7 Total liabilities and owners' equity $152.3 important to the cash flow of the business since the longer it takes for customers to pay their bills, the more stress is placed on the cash needs of the venture. A more detailed discussion of the management of receivables is presented in Chapter 13. liabilities Money that is • Liabilities. These accounts represent

- 45. everything owed to creditors . Some of these owed to creditors amounts may be due within a year (current liabilities), and others may be long-term debts . There are no long-term liabilities in our MPP Plastics example because the venture used funds from the founders to start the business. However, should the entrepreneurs need to borrow money from a bank for the future purchase of equip- ment or for additional growth capital, the balance sheet would show long-term lia- bilities in the form of a note payable equal to the principal amount borrowed. As stated earlier, any interest on this note would appear as an expense in the income statement, and the payment of any principal would be shown in the cash flow state- ment. Subsequent end-of-year balance sheets would show only the remaining amount of principal due on the note payable. Although prompt payment of what is owed (payables) establishes good credit ratings and a good relationship with suppli- ers, it is often necessary to delay payments of bills to more effectively manage cash flow. Ideally, any business owner wants bills to be paid on time by suppliers so that he or she can pay any bills owed on time. Unfortunately, during recessions , many -~- } 0!' __ ~ _ _'"'~-"""""'h"'--------- ------------------------------ --------------------------- <iiH

- 46. 294 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN owner equity The amount owners have invested and/or retained from the venture operations breakeven Volume of sales where the venture neither makes a profit nor incurs a loss firms hold back payment of their bills to better manage cash flow. The problem with this strategy is that while the entrepreneur may think that slower payment of bills will generate better cash flow, he or she may also find that customers are think- ing the same thing, with the result that no one gains any cash advantage. More discus- sion of this issue is also included in Chapter 13. • Owner equity. This amount represents the excess of all assets over all liabilities. It represents the net worth of the business. The $300,000 that was invested into the business by MPP Plastics' three entrepreneurs is included in the

- 47. owners' equity or net worth section of the balance sheet. Any profit from the business will also be included in the net worth as retained earnings. In our MPP Plastics example, retained earnings is negative, based on the net loss incurred in year 1. Thus, revenue increases assets and owners' equity, and expenses decrease owners' equity and either increase liabili- ties or decrease assets. BREAK- EVEN ANALYSIS In the initial stages of the new venture, it is helpful for the entrepreneur to know when a profit may be achieved. This will provide further insight into the financial potential for the start-up business. Break-even analysis is a useful technique for determining how many units must be sold or how much sales volume must be achieved to break even. We already know from the projections in Table 10.3 that MPP Plastics will begin to earn a profit in the eleventh month. However, this is not the break- even point since the firm has obligations for the remainder of the year that must be met, regardless of the number of units sold. These obligations, or fixed costs, must be covered by sales volume for a company to break even. Thus, breakeven is that volume of sales at which the business will neither make a profit nor incur a loss. The break-even sales point indicates to the entrepreneur the volume of sales needed to cover total variable and fixed expenses. Sales in excess of the

- 48. break-even point will result in a profit as long as the selling price remains above the costs necessary to produce each unit (variable cost).6 The break-even formula is derived in Table 10.8 and is given as: B/E(Q)= TFC SP- VC/Unit (marginal contribution) where B/E(Q) =break-even quantity TFC = total fixed costs SP = selling price VC /Unit = variable costs per unit As long as the selling price is greater than the variable costs per unit, some contribution can be made to cover fixed costs. Eventually, these contributions will be sufficient to pay all fixed costs, at which point the firm has reached breakeven. The major weakness in calculating the breakeven lies in determining whether a cost is fixed or variable. For new ventures these determinations will require some judgment. How- ever, it is reasonable to regard costs such as depreciation, salaries and wages, rent, and in- surance as fixed. Materials, selling expenses such as commissions, and direct labor are most likely to be variable costs. The variable costs per unit usually can be determined by allocating the direct labor, materials, and other expenses that are incurred with the produc- tion of a single unit.

- 49. '"'"'""'""h;p, E;ghth Ed;Uoo I 305 ------~------------------------ --- -------- - --- -------- -------- ·- ---------------~-~~-- CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 295 TABLE 10.8 Determining the Break-Even Formula By definition, breakeven is where Total Revenue (TR) Also by definition: (TR) and (TC) Thus: SP X Q = TFC + TVC Where TVC Thus SP X Q = TFC + (VC/Unit X Q) (SP X Q)- (VC/Unit X Q) Q (SP - VC/Unit) Finally, Breakeven(Q) = Total Costs (TC) =Selling Price (SP) x Quantity (Q) =Total Fixed Costs (TFC}* +Total Variable Costs (TVC)t

- 50. = Variable Costs/Unit (VC/Unit)* X Quantity (Q) = TFC = TFC TFC SP- VC/Unit *Fixed costs are those costs that, without change in present productive capacity, are not affected by changes in volume of output. !Variable costs are those that are affected in total by changes in volume of output. *The variable costs per unit is all those costs attributable to producing one unit. This cost is constant within defined ranges of production . Recall that in our MPP Plastics example the venture produces plastic molded parts for the toy industry and hard goods and appliance manufacturers. Since the company is likely to be selling a large volume of these parts at various prices, it is necessary to make an assumption regarding the average selling price based on production and sales revenue. The entrepreneurs determine that the average selling price of all these compo- nents is $4.00/unit. From the pro forma income statement (Table 10.4), we see that fixed costs in year 1 are $636,300. We also know from our example that cost of goods sold is

- 51. 50 percent of sales revenue, so we can assume a variable cost per unit of $2.00. Using these calculations we can then determine the venture's break- even point (B/E) in units as follows: TFC B/E=----- SP- VC/Unit $636,300 $4.00 - $2.00 $636,300 $2.00 = 318,150 units Any units beyond the 318,150 that are sold by the venture will result in a profit of $2.00 per unit. Sales below this number will result in a loss for the company. In cases where the firm produces more than one product and it is feasible to allocate fixed costs to each product, then it is possible to calculate a break-even point for each product. Fixed costs are deter- mined by weighting the costs as a function of the sales projections for each product. For ex- ample, if it is assumed that 40 percent of the sales are for product X, then 40 percent of fixed costs should be allocated to that product. In our MPP Plastics example, the large number of different products and the size lots of

- 52. customer purchases prohibit any individual product break-even calculation. In this case we estimate the average selling price of all components for use in our calculations. 30~-~ Entrepreneurship 296 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN pro forma sources a11d applicatio11s offtmds Summarizes all the projected sources of funds available to the venture and how these funds will be disbursed FIGURE 10.1 Graphic Illustration of Breakeven $ ooos 1,500 1,400 1,300

- 53. 1,200 1,100 1,000 900 800 700 .....- !-' FC 600 500 400 300 200 100 100 200 300 Units (OOOs) 400 500 One of the unique aspects of breakeven is that it can be graphically displayed, as in Figure 10.1. In addition, the entrepreneur can try different

- 54. states of nature (e.g., different selling prices, different fixed costs and/or variable costs) to ascertain the impact on breakeven and subsequent profits. PRO FORMA SOURCES AND APPLICATIONS OF FUNDS The pro forma sources and applications of funds statement illustrates the disposition of earnings from operations and from other financing. Its purpose is to show how net income and financing were used to increase assets or to pay off debt. It is often difficult for the entrepreneur to understand how the net income for the year was disposed of and the effect of the movement of cash through the business. Questions often asked are, Where did the cash come from? How was the cash used? and What happened to asset items during the period? Table 10.9 shows the pro forma sources and applications of funds for MPP Plastics Inc. after the first year of operation. Many of the funds were obtained from personal funds or loans. Since at the end of the first year a profit was earned, it too would be added to the sources of funds. Depreciation is added back because it does not represent '""'P""'""hip, Eigh<h Editioo I 307 -- ----- -·-- -- . -- ·- ~-- ~~ AS SEEN IN BUSINESSWEEK

- 55. ELEVATOR PITCH FOR BEER CHIPS When Brett Stern sees a problem, he fixes it. A life- long tinkerer, the 50-year-o ld inventor used his ex- pertise in industrial design to market snack foods. Unable to find a beer-flavored potato chip, Stern w hipped up his own batch. Within two years, he w as shipping packages of aptly named Beer Chips, w hich retail from $1.39 to $3 .60, to Whole Foods (WFMI), SuperValu (SVU), and Publix grocery stores. Stern used $11,200 of his own money to launch the Portland (Ore.) company. He says he generated $500,000 in revenue in 2007 and $1.3 mi Ilion in 2008. He claims a profit margin of 11 %, which he cr edits to his virtual business model: He outsources everything but the creativity. Controlling only the d esign and direction of the product, he relies on ot hers to manufacture and distribute it. That keeps is overhead low: His only employees-a book- Keeper and a marketer-both work part time from a garage. Stern, who's known to carry chip samples in his car and give them to strangers, also keeps his eye on the big picture . He hopes to create enough de- mand for Beer Chips, with such new flavors as mar- garita and Bloody Mary, that a snack-food company will purchase it.* A business associate has asked you to look for in- teresting investment opportunities in the snack-food market. He is willing to pay you a finder's fee if you provide a good investment opportunity. After learn- ing about this start-up, you need to decide whether to introduct Brett to your business associate. What would you do? Why would this be a good long-term

- 56. investment, and what would be the risks? *Source: Reprinted from June 9, 2009 issue of Business Week by special permission, copyright© 2009 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., "America's Most Promising Startups: Beer Chips." by Emily Schmitt, posted on June 9, 2009, www.businessweek.com/smallbiz/ an out-of-pocket expense. Thus, typical sources of funds are from operations, new invest- ments, long-term borrowing, and sale of assets . The major uses or applications of funds are to increase assets, retire long-term liabilities, reduce owner or stockholders' equity, and pay dividends. The sources and applications of funds statement emphasizes the inter- relationship of these items to working capital. The statement helps the entrepreneur as well as investors to better understand the financial well-being of the company as well as the effectiveness of the financial management policies of the company. TABLE 10.9 MPP Plastics Inc., Pro Forma Sources and Applications of Funds, End of First Year Source of funds Personal funds of founders $300,000 Net income (loss) from operations (151,300) Add depreciation 14,400

- 57. Total funds provided $163,100 Application of funds Purchase of equipment $ 72,000 Inventory 1,200 Total funds expended 73,200 Net increase in working capital 89,900 $163,100 297 308 Entrepreneurship ,. __ _ 298 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN IN REVIEW SUMMARY SOFTWARE PACKAGES There are a number of financial software packages available for the entrepreneur that can track financial data and generate any important financial statement. For purposes of com- pleting the pro forma statements, at least in the business planning stage, it is probably eas- iest to use a spreadsheet program, since numbers may change often as the entrepreneur

- 58. begins to develop budgets for the pro forma statements. Microsoft Excel is the most widely used spreadsheet software and is available in Macintosh and PC formats. The value of using a spreadsheet in the start-up phase for financial projections is simply be- ing able to present different scenarios and assess their impact on the pro forma statements. It helps to answer such questions as, What would be the effect of a price decrease of 10 percent on my pro forma income statement? What would be the impact of an increase of 10 percent in operating expenses? and How would the lease versus purchase of equipment affect my cash flow? This type of analysis, using the computer spreadsheet software, will provide a quick assessment of the likely financial projections given different scenarios. It is recommended in the start-up stage, where the venture is very small and limited in time and resources, that the software selected be very simple and easy to use. The entrepre- neur will need software to maintain the books and to generate financial statements. Most of these software packages allow for check writing, payroll, invoicing, inventory manage- ment, bill paying, credit management, and taxes. The software packages vary in price and complexity. The simplest to use and least expen- sive ($79 to $140) software products are QuickBooks (Intuit Inc.), Peachtree (Sage Software), Microsoft Office Accounting, and CheckMark Software Inc. These packages offer basic pay-

- 59. roll and general ledger accounting software for the start-up venture. They typically offer tutorials and support geared toward the successful implementation of these packages, partic- ularly for new users. All these firms offer more comprehensive accounting software, as do many other companies. Prices for these packages can range from $199 to $999 (and up) depending on the comprehensiveness of the software. A simple Internet search will identify hundreds of accounting software companies. The most basic and most popular comprehen- sive packages are mentioned in the preceding, and these usually can be purchased online or at a local computer store. If a more comprehensive package is needed, the entrepreneur should discuss the options with a business associate, friend, or consultant who can assess his or her needs, evaluate the benefits of the most appropriate options, and assist the entrepreneur in selecting the package that will best fit the venture's needs. This chapter introduces several financial projection techn iques. A single fictitious ex- ample of a new venture (MPP Plastics Inc.) is used to illustrate how to prepare each pro forma statement. Each of the planning tools is designed to provide the entrepreneur w ith a clear picture of where funds come from, how they are disbursed, the amount of cash availab le, and the general financial well-being of the new venture. The pro forma income statement provides a sales estimate in the first year (monthly

- 60. basis) and projects operating expenses each month. These estimates are determined from the appropriate budgets, which are based on marketing plan projections and objectives. I "''"'""'""h;p, E;gh<h "";'" I 309 --------------- ---~------------~---- ·-·---·- ------ --- ·----- ----~---··-··--~-------- ----t --- CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 299 Cash flow is not the same as profit. It reflects the difference between cash actually received and cash disbursements. Some cash disbursements are not operating expenses (e.g., repayment of loan principal); likewise, some operating expenses are not a cash disbursement (e.g., depreciation expense). Many new ventures have failed because of a lack of cash, even when the venture is profitable. The pro forma balance sheet reflects the condition of the business at the end of a particular period. It summarizes the assets, liabilities, and net worth of the firm. The break-even point can be determined from projected income. This measures the point where total revenue equals total cost. The pro forma sources and applications of funds statement helps the entrepreneur

- 61. to understand how the net income for the year was disposed of and the effect of the movement of cash through the business. It emphasizes the interrelationship of assets, liabilities, and stockholders' equity to working capital. Software packages to assist the entrepreneur in accounting, payroll, inventory, billing, and so on are readily available. The cost of these packages will vary depending on the size and type of business. RESEARCH TASKS 1. Research the software packages available to help entrepreneurs with the financials for a business plan. Which do you believe is the best? Why? 2. Companies planning to make an initial public offering (IPO) must submit a financial plan as part of their prospectus. From the Internet, collect a prospectus from three different companies and analyze their financial plans. What were the major assumptions made in constructing these financial plans? Compare and contrast these financial plans with what we would expect of a financial plan as part of a business plan. 3. Find an initial public offering prospectus for three companies. What items are listed as assets? As liabilities? How much is the owners' equity? For what purpose do they say they are going to use the additional funds raised

- 62. from the initial public offering? CLASS DISCUSSION 1. Is it more important for an entrepreneur to track cash or profits? Does it depend on the type of business and/or industry? What troubles will an entrepreneur face if she or he tracks only profits and ignores cash? What troubles will an entrepreneur face if she or he tracks only cash and ignores profits? 2. What volume of sales is required to reach breakeven for the following business: The variable cost of producing one unit of the product is $5, the fixed costs of plant and labor are $500,000, and the selling price of a single product is $50. It is not always easy to classify a cost as fixed or variable. What happens to the breakeven calculated above if some of the fixed costs are reclassified as variable costs? What happens if the reverse is the case (i.e., some of the variable costs are reclassified as fixed costs)? 3. How useful is a financial plan when it is based on assumptions of the future and we are confident that these assumptions are not going to be 100 percent correct? I 31 0 j Entrepreneursh ip

- 63. __ ,_. ____ ·~--+----- - -- ----·--------- ------------------------------ ----- ----- ------~----- ----------------- ---- 300 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN SELECTED READINGS Adelman, Philip J.; and Alan M. Marks. (2007}. Entrepreneurial Finance-Finance :=: Small Businesses, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice- Hall. A practical-oriented text that focuses specifically on the needs of individuals sta-- ing their own businesses. Its emphasis is on financial issues for proprietorsh~ partnerships, limited liability companies, and S corporations. A unique chapter -- personal finance has been added in this edition. Bogoslaw, David. (November 11, 2008). How to Fix Financial Reporting, Business ~ Online, p. 14. Twenty of the wealthiest countries sent their finance ministers to a conference := discuss how to overhaul the global financial system. Basically, there needs to be= change in how companies think about capital markets, and they need to work mo~ closely with customers, employees, and their supply chains. In addition, the au argues that changes are needed in the U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Prin

- 64. pies (GAAP). Carter, Richard B.; and Howard Van Auken. (2005}. Bootstrap Financing and Owne Perceptions of Their Business Constraints and Opportunities. Entrepreneurship and Re- gional Development, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 129-44. The results of a regional survey of small-business entrepreneurs are presentee These entrepreneurs were queried regarding their use of and their motivation use bootstrap financing. Extending the work of Winborg and Landstrom, these results indicate that perceived risk is highly associated with the owners' assess- ment of the importance of bootstrap financing techniques. The results sho ul· be helpful to consultants and agencies that assist small firms with fundin~ alternatives. Gahagan, Jim. (2004). Reaching for Financial Success. Strategic Finance, vol. 20, no . 7. pp. 12-13. This article discusses the importance of reaching financial success for a business en- terprise. As market conditions change dramatically within a single planning perio d, budgeting and planning forecasts and the financial plans they produce are critica to the business owner. Jones, Craig. (February 2008). Reducing Operating Costs through Innovation. Conve-

- 65. nience Store Decisions, pp. 6-8. A small-business owner of a service center and car wash discusses how he was ab le to reduce costs through the integration of energy-cost-saving strategies. Not only were costs reduced, but profits and convenience to the employees and customers were increased. Jordan, Charles E.; and Marilyn A. Waldron. (2001). Predicting Cash Flow from Opera- tions: Evidence on the Comparative Abilities for a Continuum of Measures. Journal of Applied Business Research, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 87-94. Prior studies have attempted to confirm or reject the assertion that accrua l accounting measures provide better information for predicting cash flows than do cash basis measures. However, their results have proved largely inconclusive and contradictory. This study identifies research constructs that may have driven these inconsistent findings and makes adjustments to mitigate their effects. Rappaport, Alfred. (2005}. The Economics of Short-Term Performance Obsession. Finan- cial Analysts Journal, vol. 61, no. 3, pp. 65-79. This article focuses on a three-pronged program for reducing short-term corpo- rate performance obsession. The author argues that short-term performance is

- 66. D NOTES Eo<repre"'""h;p, E;ghth Ed;t;oo I 311 -- ---·- ---· ----- -- -~- ~-------· CHAPTER 10 THE FINANCIAL PLAN 301 particularly important to young companies. However, it is important to recognize that because there is such flexibility in estimating the timing of accruals, these short-term performance predictions may not accurately picture the cash flow forecasts. Rezaee, Zabihollah. (February 2003). High-Quality Financial Reporting: The Six-Legged Stool. Strategic Finance, pp. 26-30. This article argues that quality financial reports can be achieved when there is a well-balanced, functioning system of corporate governance. For good corporate governance, companies should develop a "six-legged stool" model that supports re- sponsible and reliable reports. The model is based on the active participation of all parties, which are: the board of directors, the audit committee, the top manage- ment team, internal auditors, external auditors, and governing bodies. Rhodes, David; and Daniel Stelter. (February 2009). Seize Advantage in a Downturn.

- 67. Harvard Business Review, pp. 50-58. The authors offer recommendations to stabilize business during a downturn. First, companies should monitor and maximize cash flow by managing customer credit and reducing working capital. Second, firms need to protect their existing business by reducing costs, managing the product line, and divesting noncore business. Third, firms need to maximize the business value relative to rivals by being proactive in investor relations. Salzman, Jessica Reagan. (November/December 2008) . Time for an End of Year Finan- cial Tune-Up. Home Business Magazine, pp. 64-67. The article offers suggestions on how small businesses can increase revenue to meet financial needs for 2009. Business owners should bill customers promptly to en- hance receivables. Bills should be paid on time to avoid late fees. Also suggestions are provided on where to find excess expenses. Tarantino, David. (September/October 2001). Understanding Financial Statements. Physician Executive, pp. 72-76. This article describes the critical"financials" that can make or break a business. It explains each financial statement, how it differs from other financial statements, and what useful information about the business can be obtained from each

- 68. statement. Taylor, Mandie. (June 2008). How to Identify Short and Long- Term Liquidity Needs Accurately. Journal of Corporate Treasury Management, pp. 291-96. The author describes the need to manage cash effectively to ensure that funding is secured at an early date. These strategies involve producing a reliable cash projection with the appropriate cash budget. This forecast or projection of cash needs is a work in progress and should be monitored regularly to ensure reliability. 1. See Sara Wilson, "Build a Billion-Dollar Business," Entrepreneur (March 2009), pp. 45-47; Jeffrey M. O'Brien, "Zappos Knows How to Kick It," Fortune (February 2, 2009), pp. 54-60; Paula Andruss, "Delivering Wow through Service," Marketing News (October 10, 2008), p. 10; and Brian Morrissey, "Zappos Launches Insights Service," Ad week (December 15, 2008), p. 6. 2. R. Kerin, S. W. Hartley, and W. Rudelius, Marketing, 9th ed. (Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2009), pp. 245-47. 312 I '"'"'""'""h;p ~ -----~·------- -------- ---·-~-----· ---·----- ·-~- ------------· ·---------- .. -------·-·--·----

- 69. 302 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNilY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN 3. E. A. Helfert, Techniques of Financial Analysis, 11th ed. (Burr Ridge, IL: McGraw-Hill/Irwin, 2003), pp. 152-78. 4. Norman Brodsky, "Learning from Mistakes," Inc. (June 2003), pp. 55-57. 5. Clyde P. Stickney, Paul Brown, and James Whalen, Financial Reporting and Statement Analysis: A Strategic Approach, 6th ed. (Florence, KY: South- Western/Cengage Learning, 2007), pp. 443-79. 6. Kerin et al., Marketing, pp. 346-50. References Hisrich, R.D., Peters, M.P., & Shepherd, D.A. (2013). Entrepreneurship (Laureate Custom Education). New York: McGraw-Hill Irwin. Custom Create Edition LAUREATE EDUCATION INC'

- 70. 264 I ,.,., .. h,, ~------------·-·--- ------ ----------·- -------------···- ---·-- THE ORGANIZATIONAL PLAN 1 To understand the importance of the management team in launching a new venture. 2 To understand the advantages and disadvantages of the alternative legal forms for organizing a new venture. 3 To explain and compare the S corporation and limited liability company as alternative forms of incorporation. 4 To learn the importance of both the formal and the informal organization. 5 To illustrate how the board of directors or board of advisors can be used to support the management of a new venture. I Entrepreneurship, Eighth Edition I 265

- 71. ---------~-- ------T --- OPENING PROFILE JIM SINEGAL Building a strong and lasting organization requires careful planning and strategy. No one knows this better than Jim Sinegal, the founder and CEO of Costco Wholesale Corporation, a successful warehouse chain store. Jim's philosophy is that a successful organization depends heavily on its employees and that happy employees are loyal • and stable and can help generate successful sales and rev- enue growth . Jim Sinegal has had a long history with the warehouse concept. It began appropriately when he was a student at San Diego State University. In 1954, a classmate and good friend asked him if he would be willing to help unload mattresses for the day at a newly opened discount store called Fed-Mart. Jim didn't realize at that time how significant this would be as an

- 72. introduction to the more modern warehouse concept. He not only went to work for Fed-Mart but he made it a career, rising eventually to executive vice president. More importantly, as part of this career at Fed-Mart, Jim was able to learn a great deal about this business from Fed-Mart's chairman, Sol Price, who is credited with being the inven- tor of the concept of high-volume warehouse stores. After many successful years working at Fed-Mart, Jim left the company in 1975 when Sol Price was fired, having sold Fed-Mart to a German retailer. Both he and Sol then teamed up to start a new warehouse company, Price Club. The success of Price Club attracted competition from Wal-Mart, which launched Sam's Club, and Zayre's, which started BJ's Wholesale Club. Noting the potential for these warehouse stores, Jim left Price Club and, with the help of a Seattle entrepreneur, launched Costco. Sol Price and Jim Sinegal became partners again in 1993 when Costco and Price Club merged to form

- 73. the largest membership cha in in the United States. In 1995, Sol Price and Jim Sinegal again parted ways, mainly because they could not agree on a strategy for building the business. Sol maintained some of the real estate and concentrated his efforts on licensing PriceSmart warehouse stores in for- eign markets. Jim retained control of all the warehouse stores in the United States and has since built the business to be the number one warehouse club operator in the country. 255 266 I Eott•Pre"'""h;p ·-- -- ---1---------- --·-- --- ··-·- -- "- -- -- - - 256 PART 3 FROM THE OPPORTUNITY TO THE BUSINESS PLAN Jim Sinegal would emphatically summarize the successful strategy of Costco in two simple statements. First, build a strong organization with loyal, hardworking employees by paying them above-average salaries (the average salary is