Grade 4 Writing Expository PromptREAD the information in

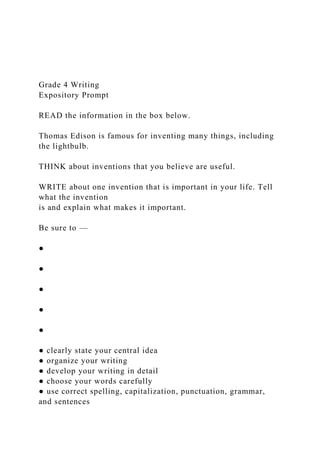

- 1. Grade 4 Writing Expository Prompt READ the information in the box below. Thomas Edison is famous for inventing many things, including the lightbulb. THINK about inventions that you believe are useful. WRITE about one invention that is important in your life. Tell what the invention is and explain what makes it important. Be sure to — ● ● ● ● ● ● clearly state your central idea ● organize your writing ● develop your writing in detail ● choose your words carefully ● use correct spelling, capitalization, punctuation, grammar, and sentences

- 2. STAAR Grade 4 Expository Texas Education Agency Student Assessment Division April 2019 Score Point 1 The essay represents a very limited writing performance. Organization/Progression ● ● ● q The organizing structure of the essay is inappropriate to the purpose or the specific demands of the prompt. The writer uses organizational strategies that are only marginally suited to the explanatory task, or they are inappropriate or not evident at all. The absence of a functional organizational structure causes the essay to lack clarity and direction. q Most ideas are generally related to the topic specified in the prompt, but the central idea is missing, unclear, or illogical. The writer may fail to maintain focus on the

- 3. topic, may include extraneous information, or may shift abruptly from idea to idea, weakening the coherence of the essay. q The writer’s progression of ideas is weak. Repetition or wordiness sometimes causes serious disruptions in the flow of the essay. At other times the lack of transitions and sentence-to-sentence connections causes the writer to present ideas in a random or illogical way, making one or more parts of the essay unclear or difficult to follow. Development of Ideas ● ● q The development of ideas is weak. The essay is ineffective because the writer uses details and examples that are inappropriate, vague, or insufficient. q The essay is insubstantial because the writer’s response to the prompt is vague or confused. In some cases, the essay as a whole is only weakly linked to the prompt. In other cases, the writer develops the essay in a manner that demonstrates a lack of understanding of the expository writing task. Use of Language/Conventions ●

- 4. ● ● q The writer’s word choice may be vague or limited. It reflects little or no awareness of the expository purpose and does not establish a tone appropriate to the task. The word choice may impede the quality and clarity of the essay. q Sentences are simplistic, awkward, or uncontrolled, significantly limiting the effectiveness of the essay. q The writer has little or no command of sentence boundaries and age-appropriate spelling, capitalization, punctuation, grammar, and usage conventions. Serious and persistent errors create disruptions in the fluency of the writing and sometimes interfere with meaning. STAAR Grade 4 Expository Texas Education Agency Student Assessment Division April 2019 Score Point 2 The essay represents a basic writing performance. Organization/Progression

- 5. ● ● ● q The organizing structure of the essay is evident but may not always be appropriate to the purpose or the specific demands of the prompt. The essay is not always clear because the writer uses organizational strategies that are only somewhat suited to the expository task. q Most ideas are generally related to the topic specified in the prompt, but the writer’s central idea is weak or somewhat unclear. The lack of an effective central idea or the writer’s inclusion of irrelevant information interferes with the focus and coherence of the essay. q The writer’s progression of ideas is not always logical and controlled. Sometimes repetition or wordiness causes minor disruptions in the flow of the essay. At other times transitions and sentence-to-sentence connections are too perfunctory or weak to support the flow of the essay or show the relationships among ideas. Development of Ideas ●

- 6. ● q The development of ideas is minimal. The essay is superficial because the writer uses details and examples that are not always appropriate or are too briefly or partially presented. q The essay reflects little or no thoughtfulness. The writer’s response to the prompt is sometimes formulaic. The writer develops the essay in a manner that demonstrates only a limited understanding of the expository writing task. Use of Language/Conventions ● ● ● q The writer’s word choice may be general or imprecise. It reflects a basic awareness of the expository purpose but does little to establish a tone appropriate to the task. The word choice may not contribute to the quality and clarity of the essay. q Sentences are awkward or only somewhat controlled, weakening the effectiveness of the essay. q The writer demonstrates a partial command of sentence boundaries and age-appropriate spelling, capitalization, punctuation, grammar, and usage

- 7. conventions. Some distracting errors may be evident, at times creating minor disruptions in the fluency or meaning of the writing. STAAR Grade 4 Expository Texas Education Agency Student Assessment Division April 2019 Score Point 3 The essay represents a satisfactory writing performance. Organization/Progression ● ● ● q The organizing structure of the essay is, for the most part, appropriate to the purpose and responsive to the specific demands of the prompt. The essay is clear because the writer uses organizational strategies that are adequately suited to the expository task. q The writer establishes a clear central idea. Most ideas are related to the central idea

- 8. and are focused on the topic specified in the prompt. The essay is coherent, though it may not always be unified due to minor lapses in focus. q The writer’s progression of ideas is generally logical and controlled. For the most part, transitions are meaningful, and sentence-to-sentence connections are sufficient to support the flow of the essay and show the relationships among ideas. Development of Ideas ● ● q The development of ideas is sufficient because the writer uses details and examples that are specific and appropriate, adding some substance to the essay. q The essay reflects some thoughtfulness. The writer’s response to the prompt is original rather than formulaic. The writer develops the essay in a manner that demonstrates a good understanding of the expository writing task. Use of Language/Conventions ● ● ●

- 9. q The writer’s word choice is, for the most part, clear and specific. It reflects an awareness of the expository purpose and establishes a tone appropriate to the task. The word choice usually contributes to the quality and clarity of the essay. q Sentences are varied and adequately controlled, for the most part contributing to the effectiveness of the essay. q The writer demonstrates an adequate command of sentence boundaries and age-appropriate spelling, capitalization, punctuation, grammar, and usage conventions. Although some errors may be evident, they create few (if any) disruptions in the fluency of the writing, and they do not affect the clarity of the essay. STAAR Grade 4 Expository Texas Education Agency Student Assessment Division April 2019 Score Point 4 The essay represents an accomplished writing performance. Organization/Progression

- 10. ● ● ● q The organizing structure of the essay is clearly appropriate to the purpose and responsive to the specific demands of the prompt. The essay is skillfully crafted because the writer uses organizational strategies that are particularly well suited to the expository task. q The writer establishes a clear central idea. All ideas are strongly related to the central idea and are focused on the topic specified in the prompt. By sustaining this focus, the writer is able to create an essay that is unified and coherent. q The writer’s progression of ideas is logical and well controlled. Meaningful transitions and strong sentence-to-sentence connections enhance the flow of the essay by clearly showing the relationships among ideas, making the writer’s train of thought easy to follow. Development of Ideas ● ● q The development of ideas is effective because the writer uses details and examples

- 11. that are specific and well chosen, adding substance to the essay. q The essay is thoughtful and engaging. The writer may choose to use his/her unique experiences or view of the world as a basis for writing or to connect ideas in interesting ways. The writer develops the essay in a manner that demonstrates a thorough understanding of the expository writing task. Use of Language/Conventions ● ● ● q The writer’s word choice is purposeful and precise. It reflects a keen awareness of the expository purpose and maintains a tone appropriate to the task. The word choice strongly contributes to the quality and clarity of the essay. q Sentences are purposeful, varied, and well controlled, enhancing the effectiveness of the essay. q The writer demonstrates a consistent command of sentence boundaries and age-appropriate spelling, capitalization, punctuation, grammar, and usage conventions. Although minor errors may be evident, they do not detract from the fluency of the writing or the clarity of the essay. The overall strength of the conventions contributes

- 12. to the effectiveness of the essay. Sample A Sample B Sample C Sample D FEATURE ARTICLE Journal of Adolescen t & Adul t L i teracy 5 7 (1) September 2 013 doi :10 .10 0 2 /JA A L . 2 0 4 © 2 013 In ternat ional Reading A ssociat ion ( pp. 31– 4 0 ) 31 Writing “Voiced” Arguments About Science Topics A N S W E R I N G T H E C C S S C A L L F O R I N T E G R A T E D L I T E R A C Y I N S T R U C T I O N

- 13. Mary Beth Monahan What happens when sixth graders write “voiced” arguments about a science-sleuth simulation? They push us to coordinate teaching strategies from disciplinary and content area literacy. With the release of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) and the attendant emphasis on an “integrated model of literacy” (National Governors Association Center for Best Practices [NGA Center] & Council of Chief State School Officers [CCSSO], 2010, p. 4), content area teachers will need support in meeting the challenge of providing robust instruction that incorporates reading, writing, listening, speaking, and viewing as vehicles for engaging students in their subject matter and building deep content knowledge (Conley, 2008). Content area teachers will also be charged with the responsibility of developing students’ proficiency in writing academic arguments across the curriculum. According to the CCSS website, “The ability to write logical arguments based on substantive claims, sound reasoning, and relevant evidence is a cornerstone of the writing standards” (For more information, see www .corestandards.org/about-the-standards/ key-points- in-english-language-arts). The challenge is thus twofold: to design

- 14. instruction that integrates the English language arts and thereby advances student engagement with and command of content area material and to teach students about the general and disciplinary- specific practices of argumentation. Given that the CCSS emphasize literacy development as a “shared responsibility” (NGA Center & CCSSO, 2010), it will be necessary for language arts and content area teachers to coordinate instructional efforts so that students develop a facility with writing arguments in different subjects, as the practices for argumentation vary according to the particular expectations of each discipline (Hyland, 2008). It will also be important for teachers to note that the standards for argument are largely silent on the issue of voice, except for the provision that writers “establish and maintain a formal style” (NGA Center & CCSSO, 2010, p. 42). Yet, what often makes arguments compelling is, in fact, voice: how writers come across as “confident” and “authoritative” (Hyland, 2008, p. 6). Mary Beth Monahan is a research assistant professor at the Vermont Reads Institute at University of Vermont, Burlington, USA; e-mail [email protected] gmail.com. JAAL_204.indd 31JAAL_204.indd 31 8/13/2013 2:50:25 PM8/13/2013 2:50:25 PM 32 J

- 16. E R A C Y 57 (1 ) S E P T E M B E R 2 01 3 FEATURE ARTICLE Likewise, writers’ credibility (i.e., how they project trustworthiness vis-à-vis sound reasoning, sufficient evidence, credible sources, and understanding of

- 17. the subject—in effect, the CCSS writing standards for argument) is conveyed through voice (Toulmin, 1958). Teachers would do well to engage students in exploring voice in argumentative discourse and how voicing practices vary across disciplines. Promoting voiced arguments can be a challenge, one that I attempted to meet as a sixth-grade teacher responsible for all subjects. The purpose of this article is to share the results of an action-research project that I undertook to evaluate my success in helping sixth graders produce voiced arguments about topics from our science curriculum (e.g., states of matter, physical and chemical changes, the water cycle). Specifically, I offer an account of my instructional approach, student writing samples, and a discussion of the potential benefits and limitations of this approach. Background on the Study: Promoting Voiced Expository Writing My motivation for developing this approach—a scientific inquiry based on an integrated model of literacy that included extensive opportunities for argumentative writing—grew from my commitment to supporting my students in meeting the standards for writing arguments. According to the CCSS (NGA Center & CCSSO, 2010), sixth graders must be able to Write arguments to support claims with clear reasons and relevant evidence: (a) Introduce claim(s) and organize the reasons and evidence clearly; (b) Support claim(s) with clear reasons and relevant evidence, using credible sources and demonstrating an understanding of the topic or text; (c) Use words, phrases, and clauses

- 18. to clarify the relationships among claim(s) and reasons; (d) Establish and maintain a formal style; (e) Provide a concluding statement or section that follows from the argument presented. (p. 42) In addition, my interest in developing an instructional program focused on voiced arguments grew from my mounting concern with students’ attitudes toward expository writing and the painful admission that the research reports they produced lacked voice—conviction, commitment, and command of the subject matter. I created a survey to gauge students’ perceptions of writing informational essays, and the results only intensified my commitment to forging an alternative approach. In the words of students: Writing an essay is like • Getting beat up by a bully • Going against a 12-foot wave • Smelly cheese • Piling up facts • Writing a paragraph These analogies revealed just how painful and perfunctory students found expository writing to be. For many, such writing was no more than a paragraph or a pile of facts. These descriptions troubled me more than the “smelly cheese” variety, because if students perceived informational writing in such finite terms, then their roles as authors would be equally limited to those of a paragraph maker and fact reporter. I wanted more for my students—I wanted them to inhabit their texts in terms that afforded agency, authority, and even power as essayists. In short, I hoped they might

- 19. project different voices when writing. And so began my campaign to raise students’ voices and the teacher-research study that gave rise to the instructional approach described herein. From the outset of this classroom-based inquiry, however, I encountered a problem: how to define voice to teach students to write voiced essays about science content. Hyland’s (2008) work on “disciplinary voice” offers such a definition. Based on his review of 240 research articles from 10 leading journals in nine disciplines, Hyland concluded that “academic writing always has voice” (p. 6) to the extent that it conveys writers’ self-representations and stances toward readers. Disciplinary voice is thus both individual and communal; the authors Hyland studied didn’t “sacrifice personal voice” but instead made “choices” to “align” themselves with “one disciplinary community rather than another” (p. 6). According to Hyland (2008), academic discourse in no way “eradicates personal choice,” because writers “still decide how aggressive, conciliatory, confident or self-effacing” (p. 6) they want to be. Writers make these decisions by determining the “level of authorized personality” (p. 7) that is sanctioned Teachers would do well to engage students in exploring voice in argumentative discourse... JAAL_204.indd 32JAAL_204.indd 32 8/13/2013 2:50:26

- 23. c ti o n within their discourse community. Although Hyland found that “writers in the humanities and social sciences take far more personal positions than those in the science and engineering fields” (p.13), he nonetheless asserts that “academic writing can’t not have voice” (p. 6). Hyland (2008) thus dismantled the false dichotomy between personal and public voice, promulgated by the historical debate among composition theorists (Elbow, 1994), that had stymied my own writing instruction. I had struggled with this same tension: whether to promote student voice (Spandel, 2009) or to groom my students to appropriate the formal registers of academic discourse (Bartholomae, 1985). However, according to Hyland, this is a false choice, because disciplinary voice is ultimately a matter of writers “recognizing and making choices from the rhetorical options in their fields” so that they are able to “convey a persona and appeal to readers from within the boundaries of their disciplines” (p. 6). Clark and Ivanič’s (1997) account of voice as “discoursal self ” also explains how writers construct self-representations as they develop greater consciousness and control over the particular discourse practices that are invoked at the moment of writing. Within any discourse—literary or scientific—“prototypical identities” are available to

- 24. writers who, in taking up the conventions of that discourse, also take up its attendant values, beliefs, and epistemologies. The selves that writers bring to the page ultimately depend on which discourses are available and, moreover, on the choices writers make from the options at hand. According to Clark and Ivanič, students’ voices—their possible textual identities—will remain limited, both if access to a range of discourses is denied and if those discoursal choices are made unconsciously. The discourse that held the most promise of raising new and improved voices was argumentative writing, given that the CCSS privileges argumentation as the means by which authors exercise their agency and power as critical, independent thinkers. In this mode of writing, I reasoned, students would be more likely to project themselves as forceful thinkers and confident knowers. Having been greatly persuaded by Bakhtin’s (1981) and Kesler’s (2012) accounts of voice as “dialogic” (born in conversation with others), I also viewed argumentation itself as the most likely medium for voiced writing. Finally, by engaging students in a lively exchange of ideas through oral and written arguments featuring science content, I was also able to redress the following shortcomings of previous instruction that had likely diminished students’ voices. Up to this point, my approach to expository writing involved teaching students to write research reports on self-selected topics. This had the unfortunate consequence of setting students up to build knowledge about their individual topics independent of one another. Lacking any opportunity

- 25. to engage in shared inquiry around a common topic, students did not benefit from the exchange of ideas that often deepens understanding. Not surprisingly, their reports suffered from superficial knowledge and treatment of topics that inevitably limited their voices as writers—their confidence and command of the material. What is more, this teaching approach privileged only one purpose of expository writing: to inform. However, as Britton, Burgess, Martin, McLeod, and Rosen (1975) explained in their seminal work on “transactional” writing, expository texts serve several purposes—to instruct, inform, or persuade—and these purposes also shape the writer’s voice quite differently. Thus, by narrowly focusing my instruction on writing to inform, I had unwittingly limited my students’ voices. Committed to expanding students’ access to a range of discourses and voice options, as Clark and Ivanič (1997) suggested, I developed a unit around the one purpose of expository writing I had overlooked: writing to persuade. Teaching my sixth graders about argumentative writing in conjunction with our shared investigation of science topics, I believed, would not only promote different voices than the research reports had, but would also engage students in a joint effort to build substantive content area knowledge by exchanging views on the topics under study. A Description of My Instruction With these aims in mind, I launched a 6-week voice unit wherein students played the roles of “science sleuths” and developed arguments to solve the

- 26. following problem (which was dramatized in a video from a commercially available program): How can a company’s frozen drink weigh more than its liquid drink, even though the two products have exactly the same ingredients and volume? Over the course of the simulation, students developed three distinct theories JAAL_204.indd 33JAAL_204.indd 33 8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM 34 J O U R N A L O F A D O LE S C

- 28. M B E R 2 01 3 FEATURE ARTICLE to explain the weight difference—frost on the bottle, cracks in the bottle, or a combination of both frost and cracks (“frocra”)—which they debated with their peers and subsequently wrote about. A problem-based inquiry appealed to me for several reasons. Foremost, it was a motivating challenge for my students, who were determined to solve the mystery at hand. Students begged to see the episode during lunch and after school, and their level of engagement was compelling in itself. But more than that, I designed the unit to capitalize on the following principles of effective argument and integrated literacy instruction. In his recent work on teaching argument, Hillocks (2011) claimed that “good arguments begin with looking at the data that is likely to become the evidence and which gives rise to a thesis statement or major claim” (p. xxi). The simulation, in effect, required students to begin with data that they would analyze and interpret, and in the process use as evidence, to support their eventual thesis about the likely cause of the weight difference.

- 29. Additionally, to reap the benefits of integrated literacy instruction, I built in opportunities for students to “manipulate” the science content by reading, writing, listening, speaking, and viewing related material (Chamberlain & Crane, 2009). First, we viewed the science-sleuth video multiple times, using various graphic organizers to help students focus their attention on critical features: the problem, likely causes of the problem, and how different characters explain the problem. During these successive viewings, students recorded information (e.g., data presented in the program, direct quotes from characters) in their science logs and prepared a range of quick-writes to clarify their evolving understanding of the problem and the content (Hohenshell & Hand, 2006). Students also participated in a variety of discussion formats—think-pair-shares, small-group conversations with fellow and rival theorists, and whole-class debriefings. The writing served as a springboard for the discussion and helped students to be better prepared to take an active role in the exchange of ideas. Likewise, the discussion afforded students an oral rehearsal for their writing, allowing them to practice articulating their theory, presenting relevant supporting evidence, and addressing counterclaims (Adler & Rougle, 2005). Students also read about the topics under study and responded to the readings by writing, drawing, and discussing the featured scientific concepts. While focusing on the science-sleuth program and integrating the English language arts to advance

- 30. students’ content knowledge during science class, I also provided explicit instruction on argument during language arts. Consistent with Ray’s (1999) “inquiry” approach, I first immersed students in a range of “mentor” texts, so they could “notice and name” the defining features of argument. During this immersion phase, I presented a series of lessons about the general model of argument outlined by Toulmin (1958) but invited my students to define each component in terms that made sense to them: claim (“taking a stand”); evidence (“how you support your theory with facts, quotes, and data”); counterclaim (“the other side”); and rebuttals (“shoot downs”). Because my primary aim was to address the CCSS writing standards for argument, I did not engage students in exploring what it means to write arguments like scientists. This, however, would be an important next step, particularly because Hyland (2008) found that of all the disciplines he investigated, engineering and science had the fewest markers of “textual voice”—expressions of writers’ “judgments, opinions, and commitments” (p. 7). I will address this limitation of my instructional approach when discussing the implications of this study. Students also participated in a debate using notes they had recorded on a graphic organizer that included the components of argument identified above. The informal writing in preparation for the debate allowed students to map out their arguments, to consolidate their thinking, and to have a reference at hand to scaffold their participation in the discussion. During the debate, representatives from the frost, crack, and frocra theories each had the opportunity to deliver opening statements that laid out their claims and

- 31. evidence. Then, each group addressed rival theorists’ counterclaims and presented rebuttals. After the debate, students did a reflective write, adding any new evidence, counterclaims, or rebuttals to their graphic organizer. Finally, to support students in writing their arguments about the science-sleuth program, I demonstrated how to write introductory, supporting, and concluding paragraphs. Based on this model, we generated a rubric that listed requirements for The writing ser ved as a springboard for the discussion... JAAL_204.indd 34JAAL_204.indd 34 8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM 35 W ri ti n g “ V o ic

- 34. te d L it e ra c y In st ru c ti o n the essay: Theory, Reasons, Direct Evidence, Solid Defense, and Paragraphing. Students then composed their arguments independently, and I continued to provide individualized support through writing conferences. Participants and Methods This study is based on the work of 26 sixth graders— 13 girls and 13 boys—who attended an upper elementary (grades 4–6) school in an affluent community of central New Jersey. There were 21 Caucasian students, two Asian American students, two Eastern Indian students, and one African American student. The class

- 35. average on the California Achievement Test was at the 87 percentile (stanine 7), which indicates an “above average” profile of academic achievement. Applying Strauss and Corbin’s (1998) grounded theory method of analysis, I coded all 26 essays to identify salient themes that suggested a theory of voiced writing grounded in the students’ work rather than based on a priori categories. Examining each student’s argumentative essay, I noted “patterned regularities” (Wolcott, 1994)—recurrent textual properties—that struck me as interesting, surprising, or significant expressions of voice. I then analyzed 11 essays that stood out as “more clearly voiced” to discover any features across these texts that suggested possible dimensions of voiced writing. I focused on students’ word choice (e.g., how they described their own and others’ theories, reasons, and evidence); sentence construction (the subjects and verbs in their sentences, as well as how they used words, phrases, and clauses to show the relationship between their and others’ claims); tone (conciliatory or adversarial); register (formal or informal style); and point of view (first, second, or third person). By focusing on these textual properties, I was able to delineate the themes of voiced argument that consistently emerged within the 11 texts. I then compared my findings from these 11 essays with the 15 others that I had rated as “less clearly voiced” to draw out any meaningful distinctions between the two text sets. When certain voice themes emerged in the more voiced essays only, I assumed that they were definitive indicators of voice. I also used themes that appeared in both sets of essays to qualify

- 36. any claims about voiced writing that were based on my initial analysis of the 11 more voiced texts. When presenting the findings of this study in the next section, I will identify student work samples by gender to illustrate the nearly equal distribution of male (six) and female (five) authors of the more voiced essays. Findings Based on my analysis of the 26 essays, I discovered three main themes that the more clearly voiced texts had in common: (1) I-ness, (2) relationship with rivals, and (3) relationship with content knowledge. Specifically, the writers’ I-ness (or presence in their texts as authors of ideas taking responsibility for their claims and openly implicating themselves as sources of knowledge) was born in a nexus of relationships, in concert with and in conflict with a number of conversational or “dialogic” partners. First Theme: I-ness The first voice property to surface in the 11 more clearly voiced texts was the students’ use of “I-statements”—first-person references—to establish themselves as the agents of the actions within their texts. The following examples from three students’ essays illustrate this trend: (1) “I have challenged this theory by recognizing its flaws”; (2) “I have proved that the crack theory could not work, not once but twice”; (3) “There is one point that the crack theorists made on their behalf that I would like to contradict.” Students adopted the first-person point of view and, with it, the respective roles of proving,

- 37. challenging, and contradicting. By using active rather than passive verbs, these students made their positions as authors clear, and, consistent with Clark and Ivanič’s (1997) description of “authorial presence” (p. 152), they also assumed full responsibility for the assertions they delivered within each clause. I-ness, as manifested in the students’ subject and verb choices, meant that they had produced voiced essays by positing a “self as author” with “something worth saying” (p. 152). With these reporting verbs, the authors also made “their commitment to [their] own the ideas” known (Clark & Ivanič, 1997, p. 134). They didn’t equivocate or maintain a neutral stance in their texts. Instead, they took a side and even rallied against other theories. As one I-statement after another made clear, these essayists achieved a far wider range of authorship than did their counterparts. They authored by “coming up with” theories, “discovering problems,” “seeking answers,” and “finding” solutions. Their visibility as authors—as the sources of ideas, data, and JAAL_204.indd 35JAAL_204.indd 35 8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM 36 J O U R

- 39. C Y 57 (1 ) S E P T E M B E R 2 01 3 FEATURE ARTICLE conclusions—far exceeded those of the less voiced texts. Through sentence construction, verb choices, and point of view, my sixth graders had established I-ness: creating a space for themselves inside their texts and insinuating themselves as authorities on the issue at hand. Second Theme: Relationship With Rivals

- 40. In one voiced essay after another, students used vivid adjectives to describe their own theories (e.g., “undoubtedly superior”) and those of others (e.g., “totally pathetic”). They also chose colorful nouns, referring to some theorists as “leaders” and to others as “total failures.” Finally, these students made dramatic verb choices, describing how they “completely destroyed” and even “disintegrated” rivals’ claims. Interestingly, several authors of the more clearly voiced essays used the expression “competing theories” when referring to the frost and crack theories. These linguistic patterns that expressed opposition were noteworthy because, within qualitative research, it is important to represent the data in the terms offered by the respondents (Merriam, 1998). As defined by my sixth graders, the second voice dimension was the “language of competition.” Because this label emerged from the essays, and specifically from the students’ adjectives, nouns, verbs, and tone—all of which implied a contest of some sort—the expression seemed “best fitted to the data” (Merriam, 1998, p. 183) in the early phase of my analysis. These combative terms and adversarial tone were hard to ignore; I had never seen students use such contentious language in expository writing. Nowhere was this type of language more evident than in their disparaging remarks about rival theorists. In fact, every one of the 11 essays included some kind of derogatory comment. According to a student who wrote an especially voiced essay, the crack theory was “unequivocally weak.” In another voiced essay, the author asked, “Is the solution the insufficient crack theory which only the minority desperately and weakly try to defend?”

- 41. Moreover, one student valorized his theory by proclaiming that it showed “more complex reasoning, a finer understanding to what occurred and, of course, a plentiful amount of evidence.” With these remarks, the student not only glorified his theory, but he also promoted himself as one capable of such advanced thinking. Another student fashioned her theory, and herself, in equally flattering terms, remarking: “The frost theory is comparatively flawless.” The words more, finer, and comparatively clearly established a relationship between competing theories. These language patterns that defined one theory in terms of the other indicated that many students had used their relationship with other theories to extol the virtues of their own. Upon closer analysis, it was clear that students had relied on the competition to embolden their claims to knowledge and to promote their theories and themselves as the authors of those theories. It is commonplace within qualitative research to draw connections between existing categories and, in the process, to develop such “links” into a workable theory that both describes and interprets the available data (Hamersley & Atkinson, 1983). I determined that such a connection existed between the categories “I-ness” and “language of competition”: Students had forged their I-ness out of the competition itself, fortifying their authorial presence by standing in opposition to other theorists. Thus, it appeared that I-ness depended on, and was only fully realized in, the students’ adversarial

- 42. relationships with other theorists. I therefore renamed the second dimension of voice “relationship with rivals,” which described the actual functions of students’ language patterns and, in effect, made clear the link between this category of voiced writing and I-ness. Third Theme: Relationship With Content Knowledge “Relationship with content knowledge,” the final category of voiced writing to surface in the data, refers to students’ manner of relating to the science-sleuth subject matter and to classmates’ treatment of that material. The authors of the more clearly voiced essays made the most of their peers’ insights to advance their own understandings. They fully participated in the rich dialogue of claims and counterclaims within their essays by interacting with others (both fellow and opposing theorists), thereby producing texts that exhibited a dialogic relationship with the science content knowledge. Students had relied on the competition to embolden their claims. JAAL_204.indd 36JAAL_204.indd 36 8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM8/13/2013 2:50:26 PM 37 W

- 44. c ie n c e T o … FEATURE ARTICLE Journal of Adolescen t & Adul t L i teracy 5 7 ( 3 ) November 2 013 doi :10 .10 0 2 /JA A L . 2 21 © 2 013 In ternat ional Reading A ssociat ion ( pp. 215 – 2 2 2 ) 215 How Rhetorical Theories of Genre Address Common Core Writing Standards Ross Collin How can content area teachers address Common Core writing standards? This article advises teachers to apply rhetorical approaches to the study of genre. In public schools throughout the United States, teachers are being called to redouble their ef-forts to help students learn to read and write texts in different content areas. This project is central

- 45. to the Common Core State Standards, which seek, among other goals, to “specify the literacy skills and understandings required for college and career readi- ness in multiple disciplines” (English Language Arts Standards/Home). Thus, in the 45 states where the Core Standards have been adopted, literacy educa- tion is expanding to include the study of discipline- based forms of communication. These reforms align with recent proposals for focusing teachers’ atten- tion more squarely on the literacies of specific disci- plines (see Moje, 2008; Pytash, 2012; Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Consistent with the Common Core’s emphasis on literacy learning in multiple domains, the initia- tive’s writing standards prompt students to compose texts for di- verse audiences and purposes. Common Core thereby promotes a rhetori- cal view of writing. By rhetoric, I mean the study of the effectiveness of different forms of communication in different domains. A rhetorician, for example, might focus on the domain of politics and study how various politicians advance their agendas by using and adapt- ing the conventions of campaign flyers. Given the Common Core’s emphasis on rhetoric, all teachers of writing—not only English language arts (ELA) teach- ers—require a pedagogical framework that shows how different forms of composition help writers build the world and act in the world in different ways. Teachers require a framework, for instance, that enables them

- 46. to highlight the forms, functions, and possibilities of letters to the editor and to distinguish these features from the forms, functions, and possibilities of lab reports. Such a framework is provided by rhetorical under- standings of genre. This claim invites four questions: 1. How has genre typically been defined in schools? 2. What is a rhetorical understanding of genre and why is it preferable to other genre theories? 3. How does the rhetorical approach re- spond to the Common Core’s promotion of Ross Collin is an assistant professor of English education at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, USA; e-mail [email protected] vcu.edu. 216 J O U R N A

- 48. 57 (3 ) N O V E M B E R 2 01 3 FEATURE ARTICLE writing for multiple purposes in multiple domains? 4. What does the rhetorical approach look like in the classroom? To answer these questions, I review the Common Core’s overall mission and its standards for writing. I show how the Common Core promotes a rhetori- cal view of composition and calls upon teachers and students to explore writing in a range of contexts. I then argue that popular genre pedagogies underex-

- 49. plain how people use genres to build and act in the world in disparate ways. These pedagogies, therefore, are unsuitable for writing lessons organized around the Core Standards. Next, in my discussion of rhe- torical theories of genre, I explain how genres may be understood as flexible resources people use to build and act in different contexts. The rhetorical approach, therefore, shares the Common Core’s interest in mat- ters of audience, purpose, and discipline. Finally, I draw upon studies of young adult writers to present snapshots of what a rhetorical approach to the teach- ing of genre looks like in classrooms. Before I begin, a few caveats are in order. Along with many other educators and researchers, I have real concerns about the Common Core. I am concerned, for instance, that the Common Core emerged out of policy circles instead of classrooms, relies on unveri- fied assumptions about standards and learning, and endorses simplistic views of the connections between education and job growth (for these and other cri- tiques, see Brady, 2012; Karp, 2012; Ravitch, 2012). Although these concerns must be addressed, I brack- et them in the present study and work to direct this unfolding initiative in a positive direction. Common Core Writing Standards Half of the Common Core’s standards are grouped into the category “Standards for English Language Arts and Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects.” The overview of this cat- egory states: Just as students must learn to read, write, speak, listen, and use language effectively in a variety

- 50. Questions of rhetoric are central to Core Standards for EL A and content area literacy. of content areas, so too must the Standards specify the literacy skills and understandings required for college and career readiness in multiple disciplines. Literacy standards for grade 6 and above are predicated on teachers of ELA, history/social studies, science, and technical sub- jects using their content area expertise to help students meet the particular challenges of read- ing, writing, speaking, listening, and language in their respective fields. (English Language Arts Standards/Home) Central to the standards for ELA and content area literacy, then, are questions of rhetoric. Students are to learn multiple forms of communication necessary for effective participation in multiple domains. The Common Core’s overall emphasis on rheto- ric is elaborated in several of the 10 writing standards for ELA and for history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Consider the following standards for both groupings: • W.2e Establish and maintain a formal style and objective tone while attending to the norms and conventions of the discipline in which they are writing. • W.4 Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style

- 51. are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience. • W.5 Develop and strengthen writing as need- ed by planning, revising, editing, rewriting, or trying a new approach, focusing on address- ing what is most significant for a specific pur- pose and audience. (English Language Arts Standards/Writing) Consider also the following standards written specifi- cally for history/social studies, science, and technical subjects: • WHST.1 Write arguments focused on disci- pline-specific content. (emphasis in original) • WHST.2d Use precise language and domain- specific vocabulary to manage the complex- ity of the topic and convey a style appropriate to the discipline and context as well as to the expertise of likely readers. (History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Standards/Writing) To meet these writing standards, teachers must focus students’ attention on the ways differ- ent contexts—including different disciplines, tasks, 217 H o w

- 53. s s C o m m o n C o re W ri ti n g S ta n d ar d s audiences, and purposes—call for different types of

- 54. communication. Specifically, teachers must work with students to explore how the form and content of a type of communication shape and are shaped by context. Such questions about text types and form- content-context relations call to mind notions of genre. In the next section, I review familiar under- standings of genre and explain how they conflict with the vision of writing advanced by the Common Core. Alternate Ways of Understanding and Teaching Genres Schools circulate many and varied genres, from hall passes to IEP forms to geometric proofs to five- paragraph essays. But the term genre is usually heard only in English classes. In such classes, genre study is most often an exercise in description and classifi- cation (for more of this critique, see Bawarshi, 2003; Devitt, 2004). For instance, when studying the genre of the sonnet, students often learn different types of sonnet rhyme schemes (e.g., the Occitan sonnet’s pattern of a-b-a-b, a-b-a-b, c-d-c-d-c-d versus the Shakespearean sonnet’s pattern of a-b-a-b, c-d-c-d, e-f-e-f, g-g). Also, students often learn how different subgenres of the sonnet develop themes in differ- ent ways across their 14 lines. When faced with an unfamiliar sonnet, students may then draw on their knowledge and place the poem in its proper category. In this typical way of teaching literary form, genres are imagined as templates or delivery systems used to present the author’s unique thoughts and feelings. Consistent with standard Western views of creativity, what is most important is the author’s personal senti- ment, which originates deep in the soul. Of second- ary importance is the form in which that sentiment is packaged and sent out into the world. Style counts, but mostly as an aid to personal expression.

- 55. This view of creativity was central to early, expres- sivist approaches to teaching the writing process (e.g., Elbow, 1975; Graves, 1983; Murray, 1968). Expressivist approaches to composition often begin with rounds of free writing, during which students put aside questions of form and pour out all their ideas on a given theme. Only after students write freely and reflect on their thoughts do they fit their writing into specific genres. Thus, as described, genre is imagined as a delivery sys- tem for preformed ideas. Although expressivist peda- gogies can foster powerful writing, they seldom focus on the rhetorical concerns of domain, task, audience, and purpose central to the Common Core. Building out from expressivist pedagogies, Hillocks (1986) and his associates (e.g., Smagorinksy, Johannessen, Kahn, & McCann, 2010) present a structured process approach to teaching composition. This approach requires students to work together (a) to engage in different writing tasks such as descrip- tion, argumentation, and narration and (b) to produce texts of different genres suited for different audiences. For instance, a science teacher might prompt students to review data about global warming and draft amicus briefs to file in support of a fictional environmental group’s lawsuit against a mining company. Crucially, however, the structured process approach separates form and function and emphasizes the latter over the former—that is, generic conventions are of secondary importance to completing writing tasks. The science class mentioned above, for example, would not spend too much time studying the form of the amicus brief. Instead, they would focus their efforts on writing out their own ideas in their own language.

- 56. While the structured process approach back- grounds questions of form, Calkins, Ehrenworth, and Lehman (2012) argue that generic conventions might be studied throughout the writing process (for a com- patible approach, see Gallagher, 2011). Describing how teachers might teach students to write the kinds of informational texts endorsed in the Core Standards, they explain: The teacher settles upon an image of informa- tional writing that he or she believes is within reach for the class, and the class as a whole talks about and annotates and analyzes the [model] text, coming to understand how it is made. We furthermore suggest teachers prioritize [model] texts in which there is a logical and visible infrastructure, perhaps shown through a table of contents that supports logically structured chapters, perhaps shown through headings and subheadings and topic sentences. (p.156) Thus, from the very beginning of the writing process, classes identify generic conventions and con- sider how they might use those conventions to create generic texts. Students learn to view generic conven- tions as integral to composition. This approach veri- fies the importance of form, but it does not clarify form’s function. That is, this approach does not show how writers use generic conventions to build and act in specific contexts. It does not, for example, help students discover how scientists use the conventions of the lab report (e.g., passive constructions) to build and act in the situation “scientists conducting and

- 58. L IT E R A C Y 57 (3 ) N O V E M B E R 2 01 3 FEATURE ARTICLE reporting on experiments.” This approach shows only

- 59. that writers use generic conventions, not why. Working outside the writing process movement, researchers in the orbit of the University of Sydney have developed a writing pedagogy focused on genre (see Christie, 1985; Cope & Kalantzis, 1993; Martin & Rose, 2008; Martin & Rothery, 1986; Reid, 1987). A key goal of this pedagogy is to help students from marginalized groups learn important genres such as petitions, letters to the editor, and job application forms. To meet this goal, the Sydney School advances a three-step process called the teaching-learning cycle. In the first step, a teacher and her students review sev- eral examples of a selected genre and discuss how the form and content of the genre fit the context in which the genre is typically used. For example, a social stud- ies teacher and her students might examine several pe- titions and note how their overviews are usually brief and made up of simple sentences. These conventions make sense for the contexts in which petitions are usu- ally presented, read, and signed: quick exchanges on the street and brief stops online. In the second step of the teaching-learning cycle, the teacher and her stu- dents work together to create a sample text by studying more closely the genre’s contexts of use, developing content area knowledge, and coauthoring and revising drafts. Finally, individual students work on their own to compose texts in the given genre. To compose their own pieces, students use the generic conventions the class identified in model texts. For instance, in a social studies class, students writing petition overviews would mobilize their knowledge of the genre and compose brief overviews made up of simple sentences. Relative to process pedagogies, the Sydney School approach brings educators closer to the kinds

- 60. of writing practices endorsed by the Common Core. The Sydney School’s attention to the relationships between form, content, and context fits with the Common Core’s emphasis on writing in different ways in different domains. Several critics, however, take issue with the Sydney School’s formulation of genre and its relation to context (see Freedman & Medway, 1994; Luke, 1996). These critics argue that the approach reifies model texts as “correct” iterations of genres. Thus, features of a context that conflict with the features of model texts too easily fall from view. For example, if a student begins her study of petitions by examining model texts with brief, sim- ply worded overviews, she may not consider writing a longer, more complex overview even when doing so makes sense for a specific context (e.g., when target- ing insiders with a petition about a highly technical matter). The Sydney School approach, therefore, can promote rigid ways of understanding genres and limit exploration and critique of the contexts in which writ- ing takes place. Given these limits, the Sydney School approach is not a good match for the Common Core. Rhetorical Views of Genre: Theory and Pedagogy Theory Over the past thirty years, rhetoricians have recon- ceived genres as “typified rhetorical actions based in recurrent situations” (Miller, 1984; see also Bawarshi, 2003; Collin, 2012, 2013; Devitt, 2004; Devitt, Reiff, & Bawarshi, 2004; Russell, 1997). Following Burke (1969), rhetoricians often define situation as a com- plex of five interconnected dimensions: scene, acts, agents, agency, and purposes (see Fig. 1). Crucially,

- 61. rhetoricians often identify a reciprocal relationship between genre and situation: One activates and shapes the other. That is, a genre provides the conven- tions, or typified rhetorical moves, that enable people to bring to life a situation’s scene, acts, agents, agency, and purposes. At the same time, a situation creates the context in which a genre and its conventions be- come meaningful. FIGURE 1 Burke’s Definition of a Situation Five dimensions of a situation Example situation: Sociologist observing events 1. Scene: Domain or thematic background 1. Scene: Sociology 2. Acts: What is happening 2. Act: Observation 3. Agents: Types of people involved 3. Agents: Sociologist and research subjects 4. Agency: What agents can and cannot do 4. Agency: Sociologists can understand social structures and processes 5. Purposes: Reasons for activities 5. Purpose: Understand observed events 219 H o w

- 63. s s C o m m o n C o re W ri ti n g S ta n d ar d s Consider the genre of the sociologist’s field jour-

- 64. nal. This genre is based in the recurrent situation “sociologist observing events” and features a range of conventions (e.g., incomplete sentences such as “man rose and left table” and split pages with just-the-facts notes in one column and questions/notes to self in an- other column). To create the situation in a particular time and place, a person with knowledge of the genre and its conventions can pick up her field journal and begin to write observation notes (act). In so doing, the writer construes herself as a sociologist (agent) work- ing in the larger domain of sociology (scene); imagines others as research subjects (agents); sees her surround- ings as a puzzle to be solved (purpose); and views her- self as being capable of solving that puzzle (agency). Importantly, the writer makes notes in accordance with sociology’s ways of seeing and thinking: She pays atten- tion to certain phenomena (e.g., patterns of interaction between men and women) and ignores others (e.g., small fluctuations in the weather). Thus, as part of her efforts to build and act in the situation “sociologist observing events,” the writer takes up the genre of the field journal and uses its conventions to make notes. To teach this genre to her class, a social studies teacher might demonstrate how the genre’s conventions (e.g., split-page notes) enable her to bring to life the scene, acts, agents, agency, and purposes characteristic of the situation “sociologist conducting observations.” Longer, more developed examples of this genre pedagogy are presented in the “Examples” section of this article. Although the Sydney school approach also iden- tifies connections between genre and situation, the rhetorical approach goes a step further to emphasize the dynamic character of the interactions of genre and situation. That is, the rhetorical approach views genre and situation as coevolving constructions. When one

- 65. changes, it pressures—but does not force—the other to change. For instance, when a sociologist engages in participant observation, she performs as a different kind of agent than she does when engaging in more traditional observation. Thus, in her field journal, she might adapt the genre’s conventions and make more notes about her own moods and opinions. Relative to a traditional observer’s field journal, then, a par- ticipant observer’s journal would feature more first- person constructions in the just-the-facts side of the notebook page (e.g., “I traded jokes with hall moni- tor”). In this way, a shift in situation elicits a shift in genre. A social studies teacher might help her class understand the dynamic relations between genre and situation by having her class use field journals to document interactions in the school’s cafeteria. Half the class could engage in traditional observation, and the other half could engage in participant obser- vation. When writing in their journals, all students would use conventions such as incomplete sentences and split-page notes. Students conducting participant observations, however, would use more first-person constructions in the just-the-facts columns of their notes than would their peers conducting traditional observations. After returning to class, students could compare and contrast the types of notes they wrote in their field journals. They could discuss how dif- ferences in their situations—traditional versus partici- pant observation—explain differences in their generic texts. Finally, the rhetorical approach views genres and situations as objects of struggle. It recognizes that interested parties struggle over the ways genres and situations are changed. For instance, sociologists

- 66. who reject participant observation as unscientific and overly subjective often critique field journals that fea- ture entries on the observer’s moods and opinions. In contrast, proponents of participant observation often critique traditional field journals for eliding the ways observers affect the actions they witness. Struggles over genre and situation, then, are often flashpoints in larger conflicts over identity (who is and who is not a real sociologist?) and the construction of a domain (what is and what is not real sociology?). A social stud- ies teacher might stage this debate by assigning stu- dents to different sides of the argument and having them use their own field journals as evidence in the debate. Students would be compelled to (a) reflect on the shifting character of sociology and sociologists and (b) consider how the beliefs of the domain are realized and struggled over in its genres. Given its attention to the complex relations be- tween text and context, the rhetorical approach to genre studies provides a framework for the kinds of writing promoted by the Common Core. The latter calls writers to learn to use “formal style…while attend- ing to the norms and conventions of the discipline in which they are writing” (W.2e); match “development, organization, and style” to “task, purpose, and audi- ence” (W.4); “write arguments focused on discipline- specific content” (WHST.1; emphasis in original); and use “domain-specific vocabulary to manage the com- plexity of the topic and convey a style appropriate to the discipline and context” (WHST.2d). Each of these concerns is brought to the fore in the rhetorical ap- proach to genre studies.

- 69. Rhetorical theories of genre have been translated into a powerful writing pedagogy by Devitt, Reiff, and Bawarshi (2004; for a compatible approach to teach- ing disciplinary genres, see Pytash, 2012). Drawing upon their years of experience teaching writing class- es, the authors present a four-step process for studying genre. Building out from this model, I add a critical turn and an extra move to create a five-step approach to rhetorical genre studies. Unlike the Sydney School’s teaching-learning cy- cle, which can begin with teachers presenting model texts out of context, the rhetorical approach begins with students finding sample texts in their natural environ- ments (step 1). Next, students collect data on how the genre is used to bring to life a situation’s scene, acts, agents, agency, and purposes. Using techniques such as observation, interviewing, and document collection, students consider (a) who uses the genre and (b) how ac- tors employ the genre to assume disciplinary identities, think in domain-specific ways, and work toward specific goals (step 2). In step 3, students analyze multiple gener- ic texts to identify patterns of form and content. They pay attention to word choice, sentence structure, topic, layout, and rhetorical appeals (i.e., appeals to reason, emotion, and identity). Next, in step 4, students con- sider how a genre’s patterns of form and content help people realize a situation’s scene, acts, agents, agency, and purposes. That is, they study how patterns of form and content enable people to set a thematic background (scene); take on social roles (agents); recognize certain possibilities (agency); perform specific actions (acts) for specific reasons (purposes); and think in domain- specific ways. In a critical turn, they consider how genres make it easier or more difficult to perform cer- tain actions and identities in a discipline. (Adapted from

- 70. Devitt, Reiff, and Bawarshi, 2004, pp. 93–94). Finally, in step 5, students compose generic texts of their own. Using their knowledge of the genre and its contexts, stu- dents compose texts that enable them to build and act in situations appropriate to the genre. Examples In a high school English class, students might inves- tigate the genre of the feature article in an online journal. Students could examine articles published on popular sites such as Salon.com, Slate.com, and NationalReview.com. Each student could collect a number of feature articles for analysis (step 1). To learn about the situation “publishing a feature ar- ticle in an online journal,” students could conduct e-mail interviews with journalists and editors (step 2). Through their interviews, students might learn that journalists and editors often evaluate the effectiveness of an article by counting the number of unique clicks it draws. While completing steps 3 and 4, students may find article titles are often more dramatic than article content—all the better to draw the maximum numbers of readers to the piece. Students may also find that journalists, convinced of readers’ fickle na- tures, front-load and condense information in their articles to make their points before readers move on. Thus, students might learn, the writer of a fea- ture article in an online journal can use and adapt the genre’s conventions to place herself in the do- main of online journalism (scene); report/analyze news (act); present herself as a journalist (agent) who understands the world (agency) and who clarifies the world’s events (purpose) for fickle readers (agents). Taking a critical turn, students can discuss the dif-

- 71. ficulty of presenting nuanced arguments in a genre characterized by dramatic titles and brief formula- tions of ideas. Finally, students might draw upon the conventions of the genre and write their own pieces for a class-produced online journal. Some students could be prompted to draw as many readers as pos- sible to their articles and to deliver content quickly to fickle readers. When writing their articles, these stu- dents might use the genre’s conventions of dramatic titles and front-loaded structure. Other students could be instructed to present nuanced analyses and to re- flect the complexities of their analyses in the titles of their articles. After all students publish their articles, students in another class could be assigned to visit the online journal and read three articles of their choos- ing. Students in the first class could count the number of clicks received by each article and then interview students in the other class about why they read or passed on specific articles. The class could discuss how the genre’s conventions helped or hindered them in attracting readers and writing nuanced arguments. In a high school chemistry class, students might study the genre of the lab report and consider how its conventions help scientists work in the situation “sci- entists conducting and reporting on experiments.” Students could gather reports from other science labs in their school or from labs in local colleges and universities. Also, students could visit working labs and gather reports from professional chemists (step 1). During their visits, students might observe scien- tists and interview them about how they compose reports to realize the situation “scientists conducting

- 74. ar d s and reporting on experiments” (step 2). Through their investigations, students might find that scientists use passive voice to background the role of individu- als in experiments (steps 3 and 4). The passivation of individuals is consistent with the discipline’s interest in replication of results. For results to be valid, they should be achievable by any scientist who follows the steps outlined in the lab report. Continuing, students might find that by using the genre’s conventions, writ- ers perform as scientists (agents) conducting experi- ments (act) in the domain of chemistry (scene). As scientists, they feel capable of understanding chemi- cal processes (agency), and they seek to devise experi- ments that yield significant, replicable … eScholarship provides open access, scholarly publishing services to the University of California and delivers a dynamic research platform to scholars worldwide. Previously Published Works UC Irvine A University of California author or department has made this article openly available. Thanks to the Academic Senate’s Open Access Policy, a great many UC- authored scholarly publications will now be freely available on this site. Let us know how this access is important for you. We want to hear your story!

- 75. http://escholarship.org/reader_feedback.html Peer Reviewed Title: Learning to write in middle school? Insights into adolescent writers' instructional experiences across content areas Journal Issue: Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 57(2) Author: Lawrence, Joshua, UC Irvine Galloway, Emily, Harvard Graduate School of Education Yim, SooBin, UC Irvine Lin, Alex Romeo, UC Irvine Publication Date: August 14, 2013 Series: UC Irvine Previously Published Works Permalink: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sn8v329 Keywords: Adolescent literacy Abstract: Despite the emphasis on increasing the frequency with which students engage in analytic writing, we know very little about the ‘writing diet’ of adolescents. Student notebooks, used as a daily record of in-class work, provide one source of evidence about

- 76. the diversity of writing expectations that students face. Through careful examination of the notebooks written by four middle-graders in 12 content area classrooms (290 texts), the present study help us to understand the ways in which these writers were acclimatized in one school year to the norms of writing in these diverse disciplinary contexts. In particular, results of this study suggest that adolescent writers may be afforded little opportunity to produce cognitively challenging genres, such as analytic essays. Notably, in content area classrooms, students engaged in very little extended writing. Copyright Information: All rights reserved unless otherwise indicated. Contact the author or original publisher for any necessary permissions. eScholarship is not the copyright owner for deposited works. Learn more at http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse http://escholarship.org http://escholarship.org http://escholarship.org http://escholarship.org http://escholarship.org/uc/uci_postprints http://escholarship.org/uc/uci http://escholarship.org/reader_feedback.html http://escholarship.org/uc/search?creator=Lawrence%2C%20Jos hua http://escholarship.org/uc/search?creator=Galloway%2C%20Em ily http://escholarship.org/uc/search?creator=Yim%2C%20SooBin http://escholarship.org/uc/search?creator=Lin%2C%20Alex%20 Romeo http://escholarship.org/uc/uci_postprints

- 77. http://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sn8v329 http://www.escholarship.org/help_copyright.html#reuse FEATURE ARTICLE Journal of Adolescen t & Adul t L i teracy x x ( x ) x x 2 013 doi :10 .10 0 2 /JA A L . 219 © 2 013 In ternat ional Reading A ssociat ion ( pp. 1–11) 1 Learning to Write in Middle School? I N S I G H T S I N T O A D O L E S C E N T W R I T E R S ’ I N S T R U C T I O N A L E X P E R I E N C E S A C R O S S C O N T E N T A R E A S Joshua Fahey Lawrence, Emily Phillips Galloway, Soobin Yim, Alex Lin Learning to write analytic genres may be particularly challenging for middle grade students because of the infrequency with which they are tasked with producing these types of texts. Math Notebook (10/16) What I look for in the equations is the quadratic term which is X2, X2, and the factor form and the factor form and the expanded form. This one is quadratic (y = X2 X2,+ 6X + 8) (written explanation of mathematical reasoning)

- 78. Social Studies Notebook (10/16) The organization of the federal courts; the court of appeals. At the next level of the federal court system is the court of appeals which handle appeals from the federal district courts. In fact, the courts of ap- peals are often called circuit courts. (notes from textbook and class) English Language Arts Notebook (10/16) Character traits What the author tells us (direct characterization). W hat the character says (indirect characterization) W hat the character thinks or feels (indirect characterization) W hat the character does (indirect characterization) (notes from textbook and class) Science Notebook (10/16) Objective: write procedures for the experiment to test the blue and gray cubes. At least 8 detailed steps. Possible vocabulary include, syringe, plunger, tubing, clamp. (notes from textbook and class) —All entries from Millie, Grade 8

- 79. Joshua Fahey Lawrence is an assistant professor at the University of California, Irvine, USA; e-mail: [email protected] uci.edu. Emily Phillips Galloway is a doctoral candidate at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA; e-mail: ecp450 @ mail.harvard.edu. Soobin Yim is a doctoral student researcher at the School of Education at the University of California, Irvine, USA; e-mail: [email protected] uci.edu. Alex Lin is a doctoral student researcher at the School of Education at the University of California, Irvine, USA; e-mail: [email protected] uci.edu. Authors (left to right) JAAL_219.indd 1JAAL_219.indd 1 8/5/2013 12:53:45 PM8/5/2013 12:53:45 PM 2 J O U R

- 81. C Y X X (X ) X X 2 01 3 FEATURE ARTICLE On a single school day, one middle school student wrote these text segments in her content area notebooks. These entries demonstrate not only the wide range of top- ics that adolescent writers must engage with as they traverse their content area classes, but also the variety of writing genres they must produce. Writing is both a support for content learning (writing to learn) and a method for assessing students’ content knowledge (writing to demonstrate learning); however, it also represents a primary medium through which stu- dents as members of a disciplinary classroom share perspectives, make reasoned arguments, and engage in dialogue (Hyland, 2005; Moje, 2008). Often, when writing for the latter purpose of producing what we have dubbed analytic genres, learners are required to interpret phenomena, add causal links, or present an argument in writing (Schleppegrell, 2004).

- 82. Thick compendia of content standards, such as the Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSS; 2010), delineate the writing genres, including many analytic genres, which adolescents are expected to proficiently produce at the end of each academic year. However, there is little institutional evidence of the so- called “writing diet”—conceptualized as the types of writing tasks completed by students during any given school day or assiduously across the school year—that supports the development of skilled writing. Yet, this information might contextualize the difficulties faced by novice writers in producing analytic writing genres on high-stakes assessments (Salahu-Din, Persky, & Miller, 2008). To provide much-needed information about the instructional experiences of young writers, in this study we examined a corpus of written work pro- duced by three seventh-grade and one eighth-grade student in 12 content area classrooms (science, social studies, math, and English) during evenly spaced in- tervals over one school year in a large urban middle school. In doing so, we begin to capture the texture of the writing diet of one sample of American ado- lescents. Specifically, the study catalogues the writ- ing genres found in students’ notebooks, commonly used as a daily record of in-class work, and examines The ability to convey complex thinking in writing is important in all disciplinar y traditions. the proportion of analytic writing produced by these

- 83. novice writers. Certainly, notebook entries are not the only form of literacy in classrooms, but in some schools, including the one in this study, they are an important daily activity across content areas. In the following sections, we present a frame for understand- ing the nature of adolescent writing tasks and then share our findings. We also consider how we may better support students in developing analytic writing skills. What Do We Know About the “Writing Diet” of Adolescent Learners? Recent large-scale studies using self-reported survey data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress suggest that, although teachers across do- mains recognize the power of writing as an assess- ment tool and support for learning content, they do not place an instructional emphasis on the produc- tion of extended composition by students; instead, they focus on notes, summaries, and short-answer questions (Applebee & Langer, 2011). Teachers of up- per elementary school students report that they teach writing for an average of 15 minutes per day and place little focus on teaching analytic writing genres (Gilbert & Graham, 2010). This suggests that stu- dents are offered little opportunity to gain proficiency in composing complex texts (Jeffrey, 2009). If knowledge is, as argued by Moje and Lewis (2007), the “residue of participation” in disciplin- ary communities, then knowledge of how to craft these high-level texts demands that students are of- fered ample opportunity to participate in these writ- ing tasks. We do not contend that adolescent writers are (or should be) engaged in producing genres that

- 84. perfectly mirror those completed by disciplinary experts. However, we do think that students should be engaged in producing increasingly complex texts in each content area, because the ability to convey complex thinking in writing is important in all dis- ciplinary traditions (Hyland, 2005; Lee & Spratley, 2010). Yet, aside from select studies based primar- ily on teacher and student self-report of writing instructional practices (Applebee & Langer, 2011), the nature of the disciplinary writing tasks that American middle grade students complete on a dai- ly basis has not, to our knowledge, been examined through document analysis, as we have done in this study. JAAL_219.indd 2JAAL_219.indd 2 8/5/2013 12:53:46 PM8/5/2013 12:53:46 PM 3 L e ar n in g t o W ri

- 88. Defining the Nature of Writing Tasks Genres or Writing Task Types We began to explore the writing lives of the learn- ers in our sample by cataloging the genres in which they wrote across content areas during 40 school days. When writing, thoughts must be encoded into pat- terns of organization, known as genres or text types (Martin, 2009). Because the term genres is polyse- mous in the literature, in this study we use it to de- scribe written texts that adopt certain grammatical forms and patterns of organization that reflect the text’s social function (e.g., to recount, to persuade, to report) (Biber & Conrad, 2009; Martin & Rose, 2008; Nunan, 2007). Schleppegrell (2004) divides genres of academic discourse into three groups: per- sonal (poem, narrative, journal), factual (summary, notes), and analytic (persuasive essay, thesis-support essay, analysis of a poem, lab reports as interpretations of observed evidence). Aligned with the language of the CCSS (2010), proficiency in analytic or analytical writing is positioned as an important skill for all learn- ers to acquire. Analytic Writing: Complex Genres Demanding Repeated Practice The analytic genre, which is cognitively and linguis- tically distinct from these other writing task types, presents particular challenges to adolescent writers (Graham & Perin, 2007b). These challenges arise, in large part, because analytic writing requires writ- ers to package knowledge in particular syntactic, lexi- cal, and discursive structures and to use new patterns of text organization (Beck & Jeffery, 2009; O’Brien, Moje, & Stewart, 2001; Schleppegrell, 2004). While

- 89. young writers generally demonstrate proficiency in organizing narrative texts by late elementary school (9–10 years old), skill at organizing expository texts seems to continue to develop well into high school (Berman & Nir-Sagiv, 2007). Unlike personal or factual genres, analytic genres require students to more frequentlymake use of logical markers of dis- course (“as a result,” “therefore”), relational verbs (“lead to,” “influenced,” “cause”), and ways of or- ganizing text (name entity, define, give causes) to construct a reasoned argument or to explain causes and effects by drawing on available evidence (Beck & Jeffrey, 2009). On a cognitive level, analytic writ- ing in the disciplines further requires knowledge of what “counts” as evidence within each discipline and skill in constructing a logical argument, which is a new and challenging task for many adolescent writers (Shanahan & Shanahan, 2008). Because learning to write is essentially a subpro- cess of the developmental sequence known as later language development (Nippold, 2007), we might imagine that, like early language skills, writing skill is developed through recursively transacting with a particular genre, both receptively and productively. From this perspective, we may expect that a support- ive instructional approach to teaching writing would include multiple opportunities to read and write a particular genre (Graham & Perin, 2007a, 2007b). Yet, developing analytic writing skill is not the sole instructional goal of most content area teachers. Presumably, when content learning is the primary instructional emphasis, writing serves the purpose of supporting students in retaining this knowledge, as when students are asked to create a glossary, produce

- 90. a summary, or engage in a quick-write after reading (Applebee & Langer, 2011). Yet, how content area teachers negotiate these complementary instructional demands to simultaneously develop students’ skill as writers and funds of disciplinary knowledge requires further documentation in the literature that seeks to describe classroom practice. To better understand the context in which writ- ing skill is acquired, this descriptive study was guided by the following questions: 1. What were the writing tasks (or genres) writ- ten across disciplines (math, science, social studies, English) by a small sample of middle school students in one academic year? 2. What was the proportion of analytic writing completed by students across disciplinary classes? Research Design and Methods Methods Research site. As you walk toward the site of our re- search, Vale Middle School, at 7:30 any weekday morn- ing during the school year, you will encounter a scene typical of many urban schools in the Northeast. Fifty to seventy students play basketball on a crowded court adjacent to the school. Members of Vale’s student body, which is predominately black and Hispanic, talk, laugh, yell, and joke around. Teachers inside prepare for a long day (7:45 a.m. to 4:00 p.m.). During the school day, the environment at Vale is orderly. Classroom pro- cedures are evident, including the cross-disciplinary use of notebooks to organize daily learning.