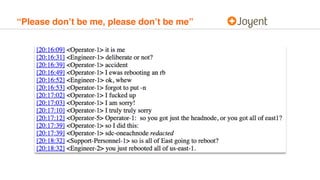

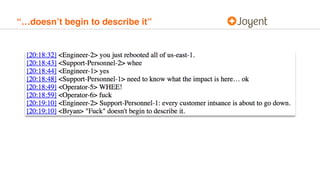

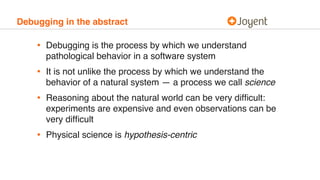

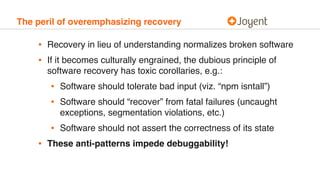

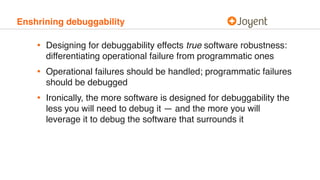

This document discusses debugging complex distributed systems during outages. It argues that debugging should be viewed not just as fixing bugs but understanding systems to improve them. Debugging requires balancing recovery and understanding during outages. Software should be designed for debuggability through instrumentation, diagnostics, and avoiding patterns that impede understanding failures. Outages provide opportunities to advance knowledge, and a culture that values debuggability leads to more robust software.