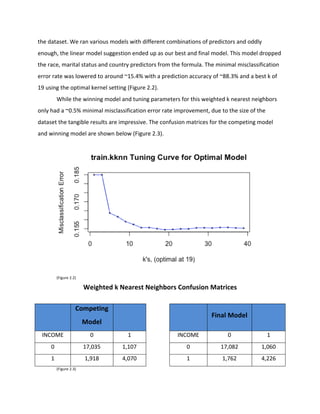

This document summarizes a study that used machine learning techniques to predict income levels using the Adult Dataset from the UC Irvine Machine Learning Repository. The author applied weighted k-nearest neighbors and random forest models to the dataset, which contains both categorical and continuous variables. Simple visualizations and linear models on education levels, age, and hours worked per week showed correlations with higher income. The results section will compare error rates from the weighted k-nearest neighbors and random forest models for predicting income levels above or below $50k.

![than

above

so

lack

of

instances

may

have

hurt

this

modeling.

I

did

not

expect

to

see

such

a

drastic

difference

in

the

two

predictions.

Appendix:

Data

Source:

Ronny

Kohavi

and

Barry

Becker

(2016).

UCI

Machine

Learning

Repository

[http://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml].

Irvine,

CA:

University

of

California,

School

of

Information

and

Computer

Science.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/30859486-c783-4234-a272-8d20e67bd998-160716015546/85/Final-Project-Statr-503-11-320.jpg)