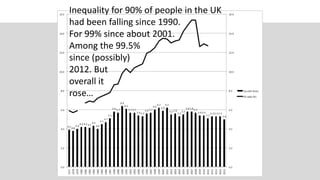

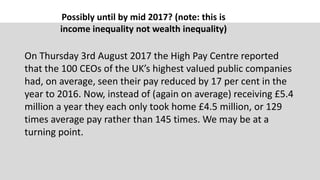

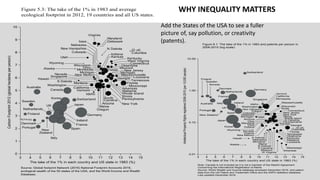

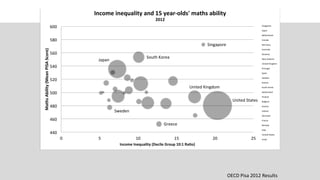

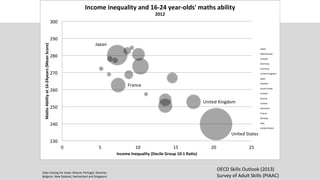

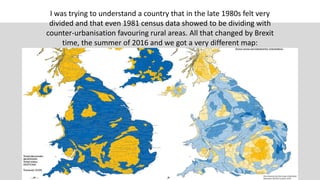

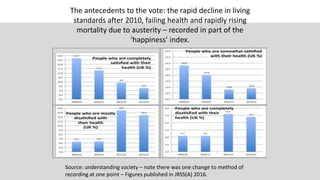

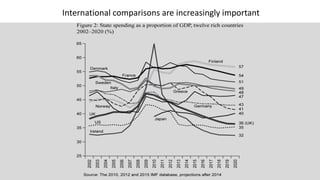

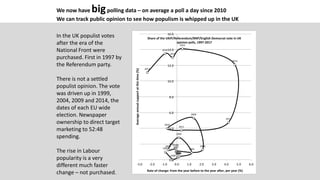

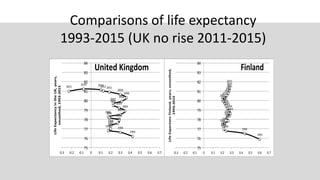

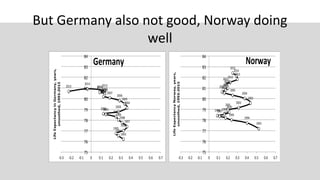

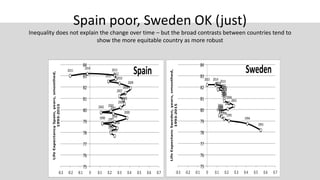

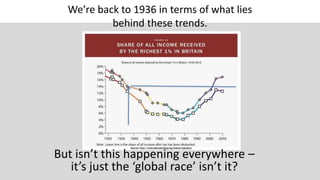

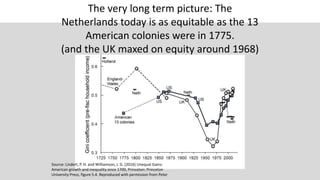

The document discusses social inequalities in the UK, emphasizing how economic factors and policies have led to a decline in living standards, particularly after austerity measures following 2010. It highlights the correlation between income inequality, health outcomes, and populist voting patterns, showcasing life expectancy trends and international comparisons. Additionally, it points out that rising inequality affects societal trust and understanding, ultimately impacting educational and economic outcomes.

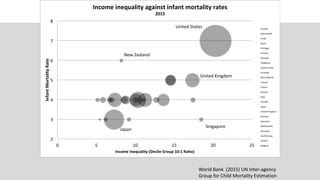

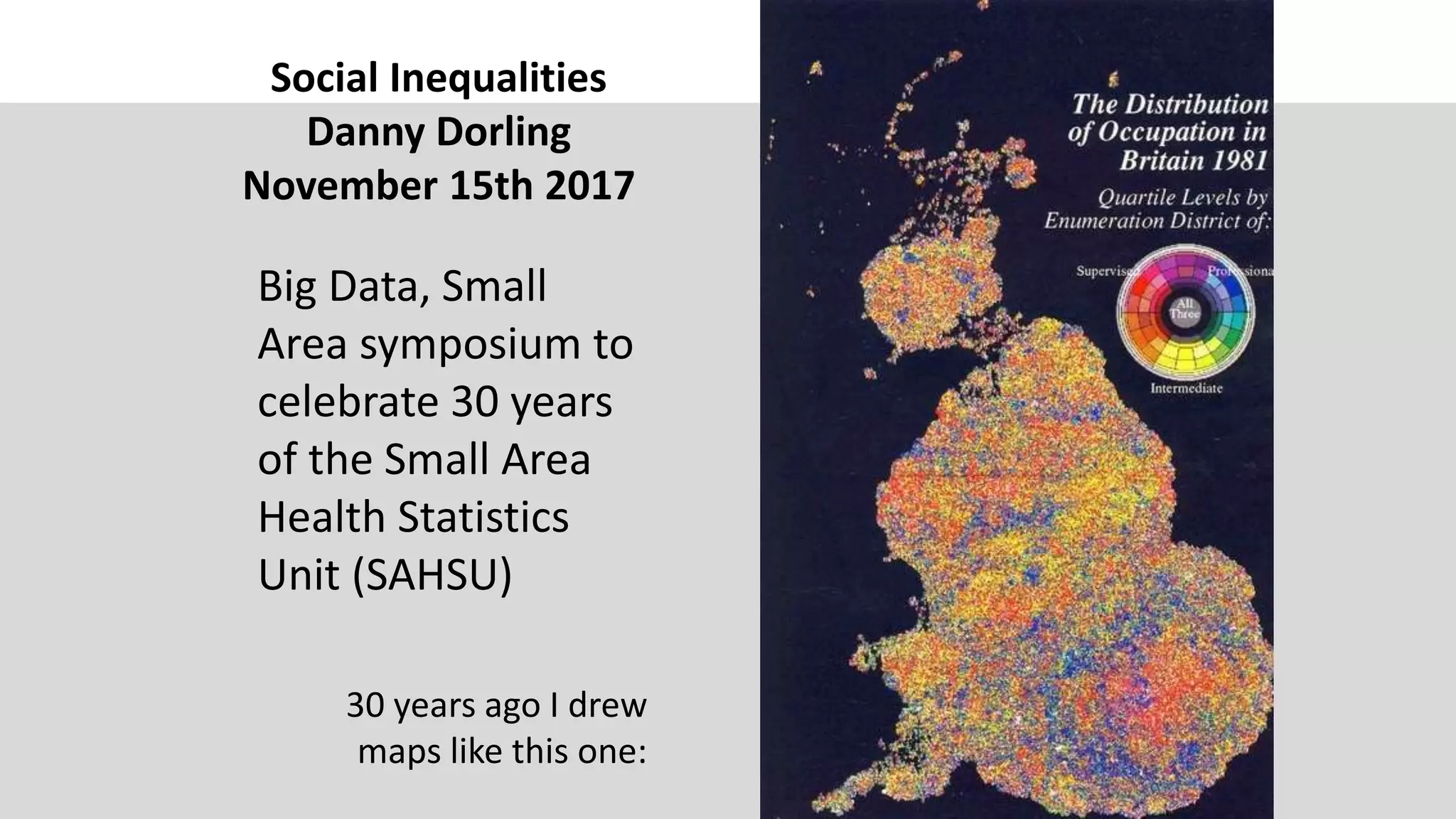

![What happens if we update the inequality

data from 2010 to 2015?

Country by 2015

(real 90:10 ratio)

Income

Inequality

United States 20.3

Singapore 18.5

Israel 17.4

United Kingdom 17.4

Canada 14.5

Spain 13.6

Greece 12.7

Italy 11.3

Ireland 11.1

Germany 10.4

Portugal 10.1

South Korea 10.1

Finland 9.2

Australia 8.8

Netherlands 8.6

New Zealand 8.2

France 7.4

Japan 7.3

Austria 7.0

Switzerland 6.7

Sweden 6.3

Norway 6.2

Belgium 5.9

Slovenia 5.5

Denmark 5.2

The small print

The richest 25 countries in the world in 2009

with populations over 1 million. According to

the IMF's World Economic Outlook Database,

April 2015, this category would now include

Kuwait, UAE, Hong Kong and Qatar in place of

Slovenia, Greece, Portugal and Spain.

Luxembourg, Iceland and San Marino are not

included given populations below 1 million.

Income is now disposable household income:

income from wages, self-employment and

capital, plus social transfers, minus direct taxes

paid. Household income is adjusted

(‘equivalised’) to take account of the amount of

scale economies that different sizes of

households can achieve. [In chart one it is more

crude].

Both the New York Times Income Distribution

Database and OECD Income Database divide all

income components by the square root of the

number of household members.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dannytalking15thnovember-171226163542/85/Social-Inequalities-19-320.jpg)