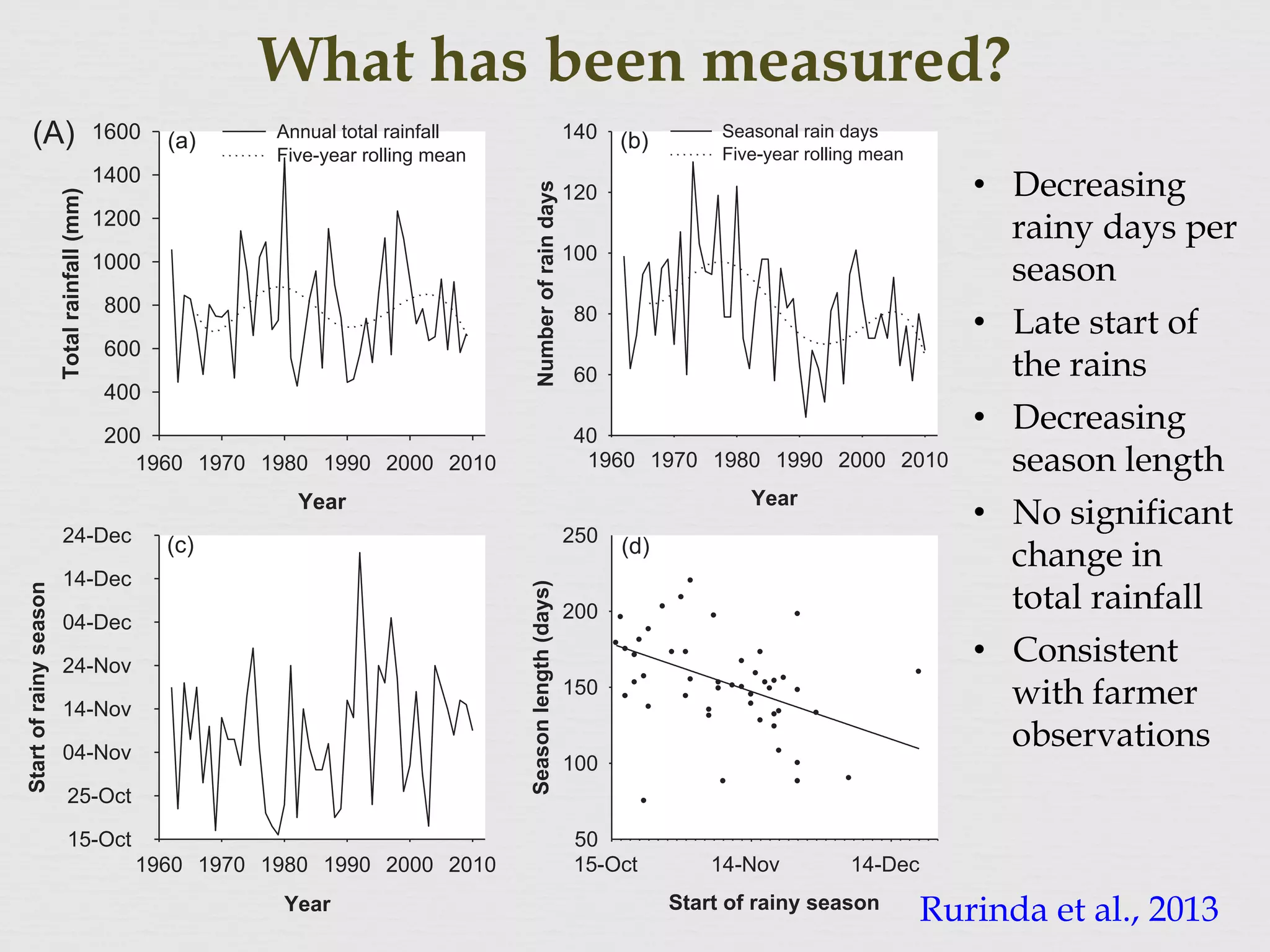

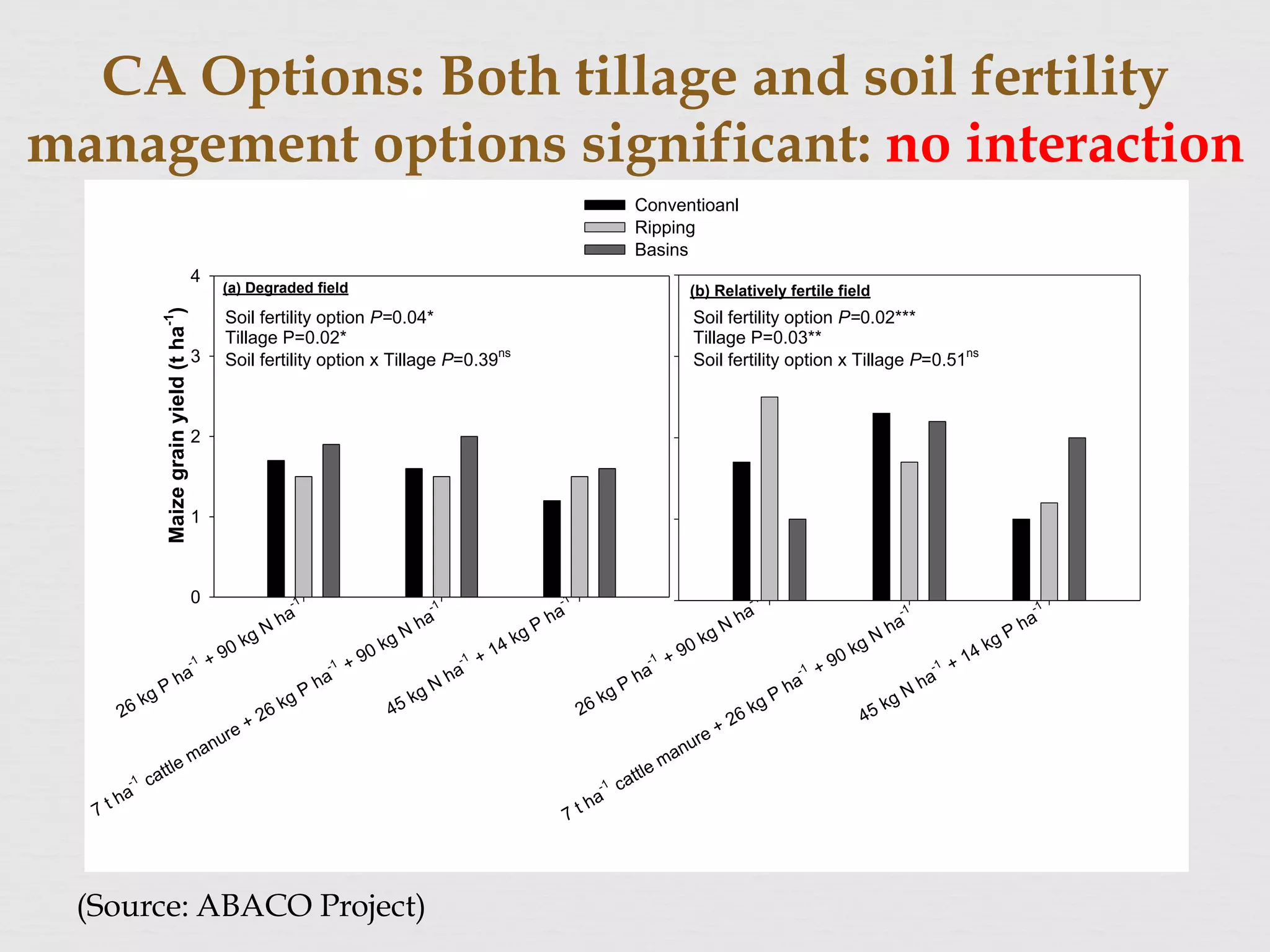

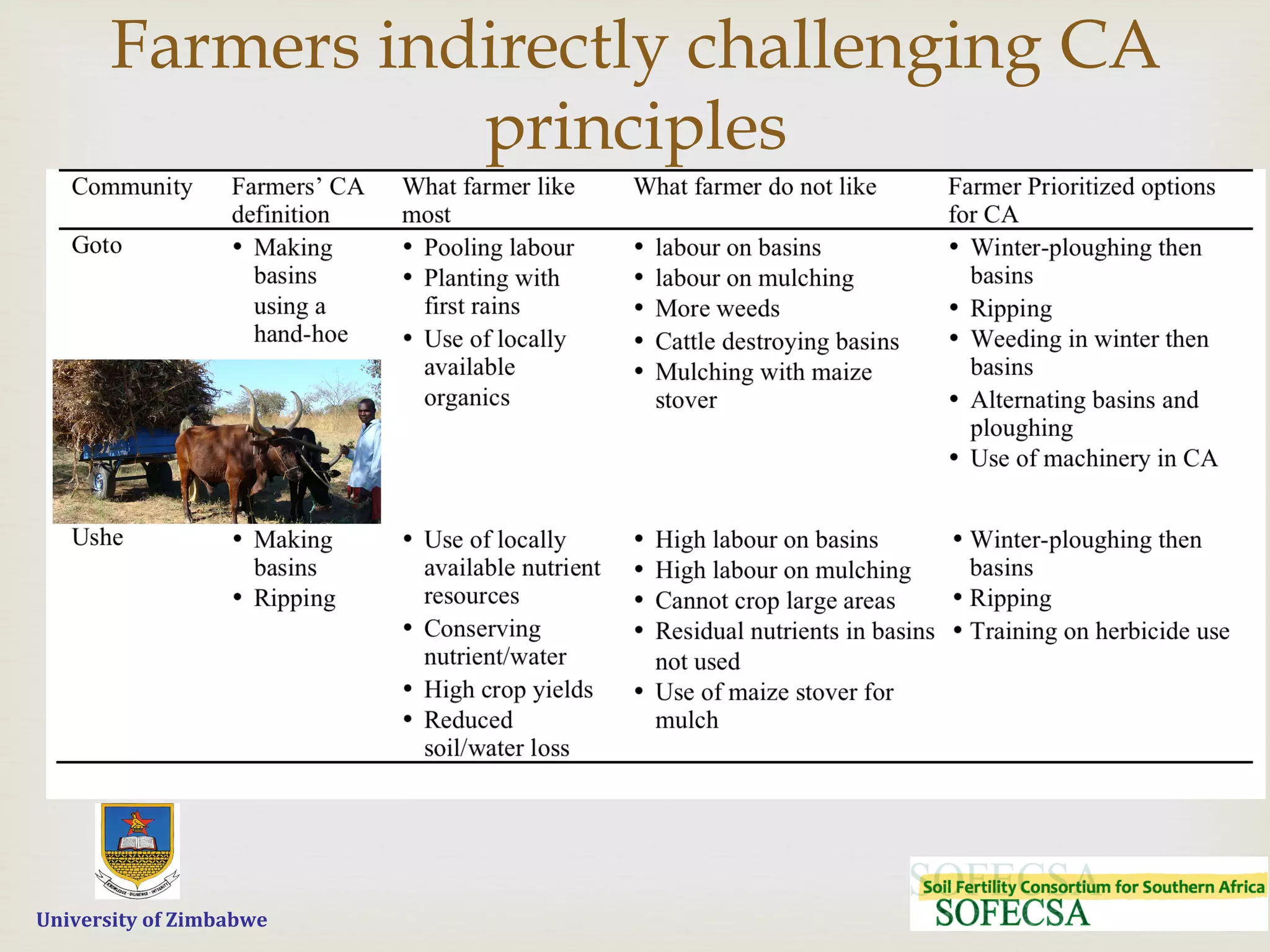

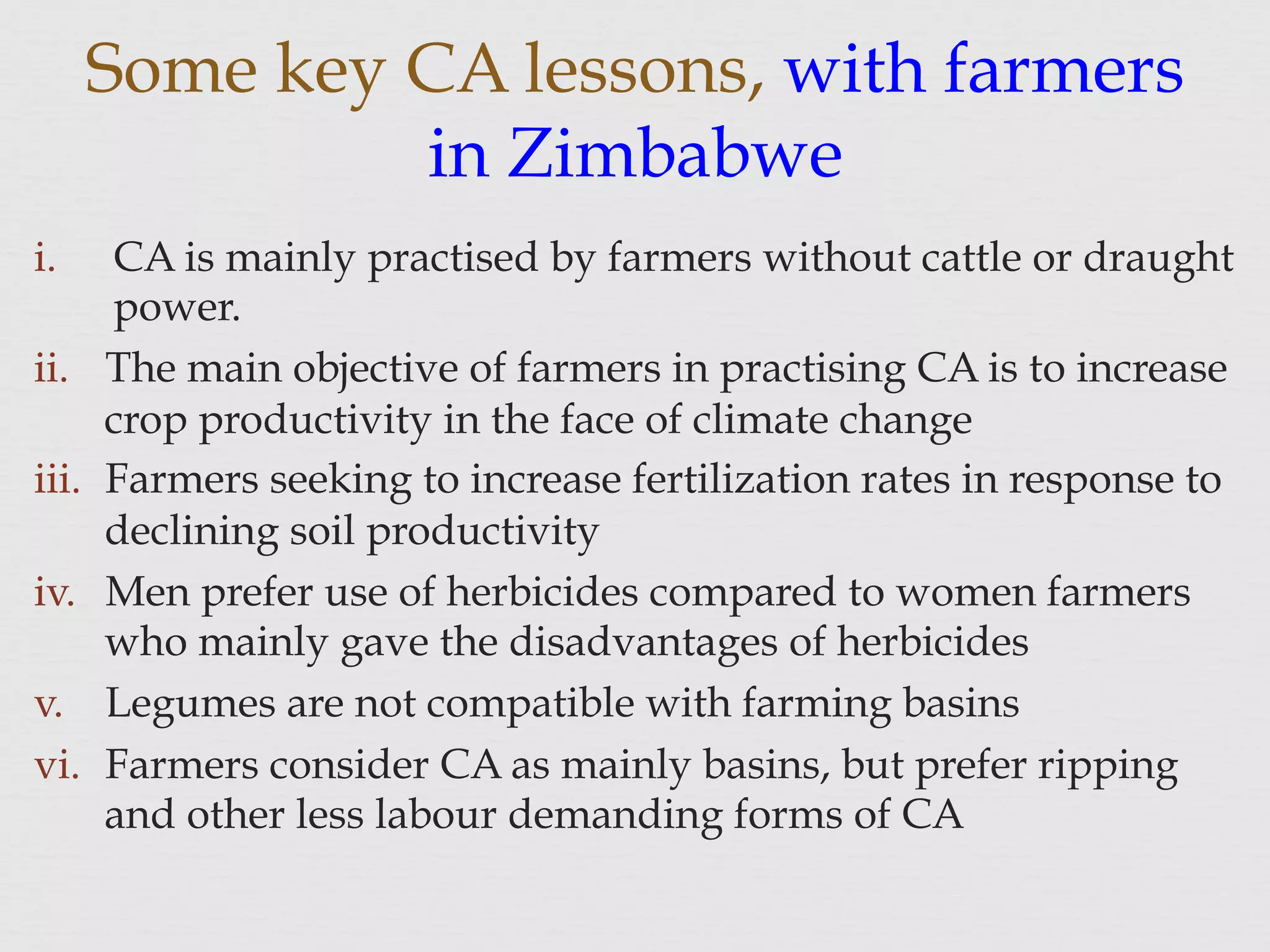

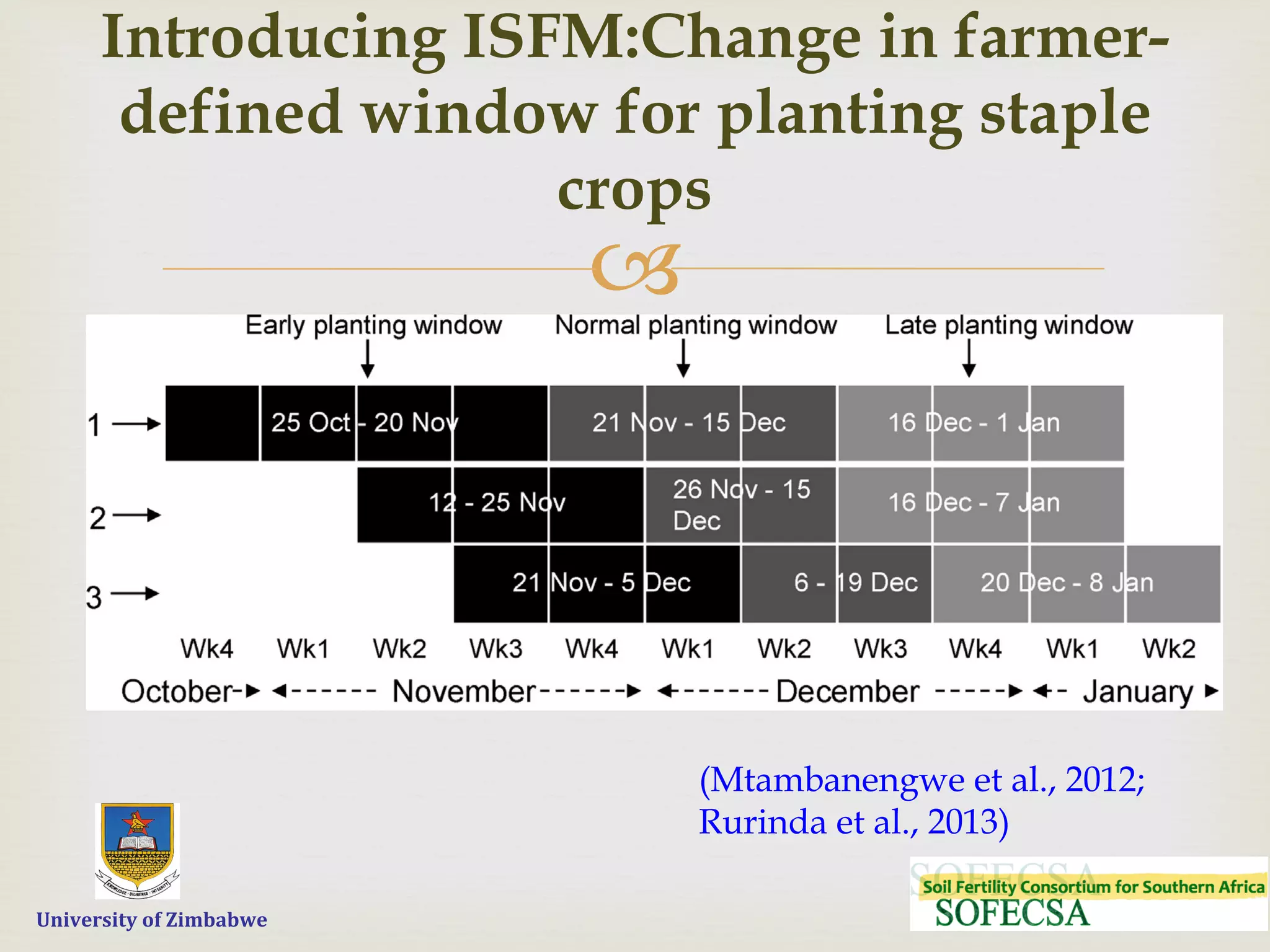

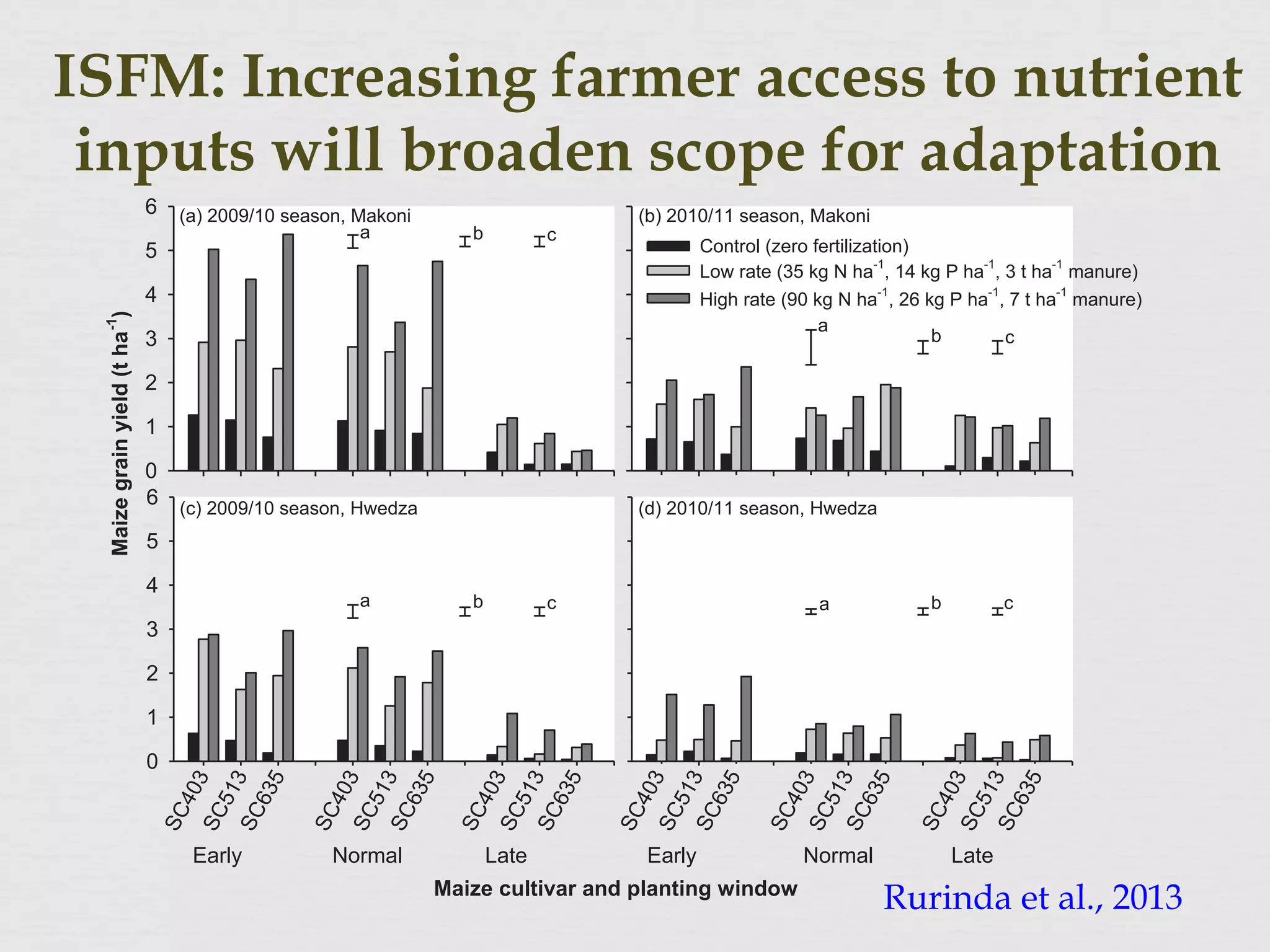

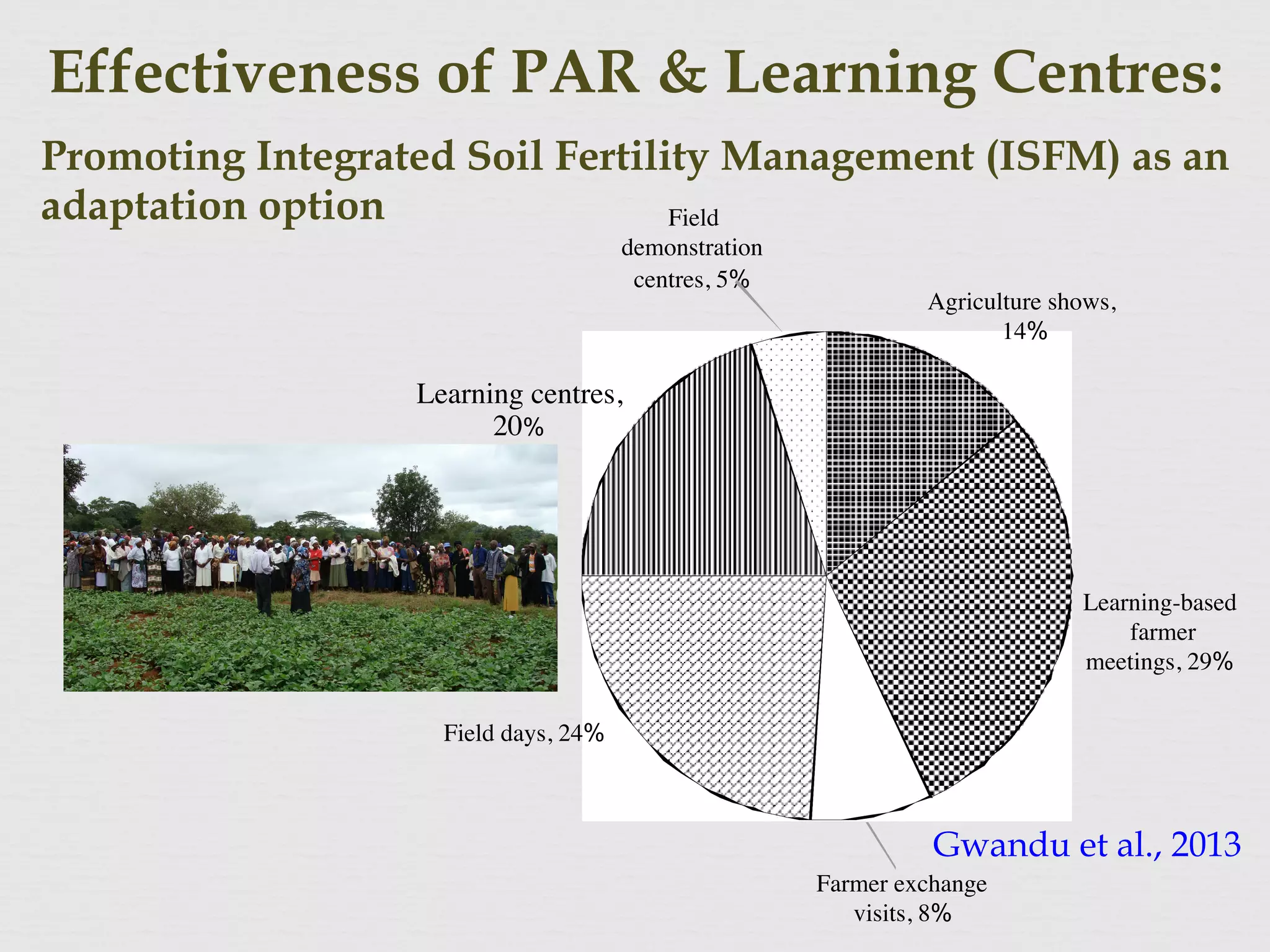

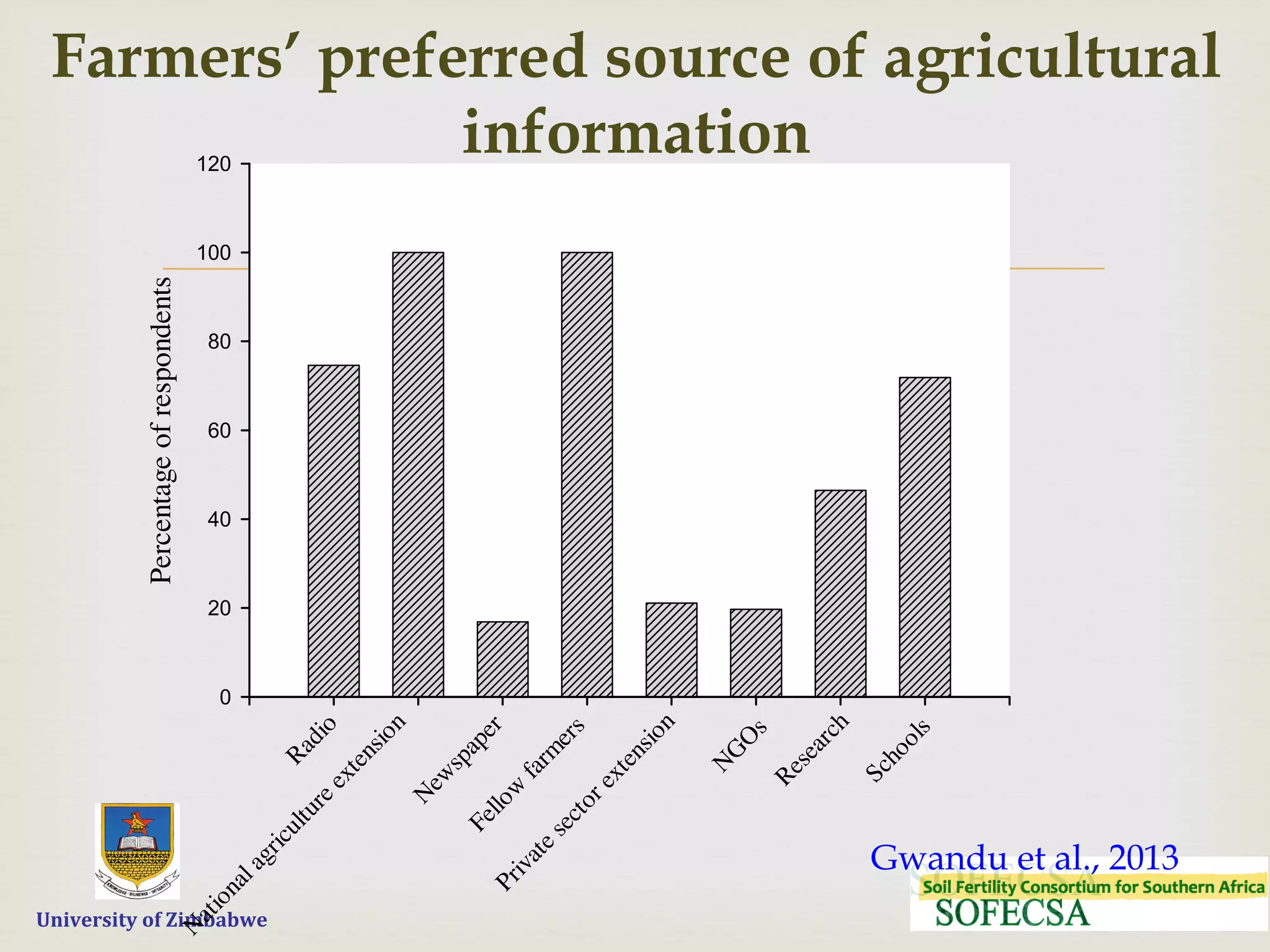

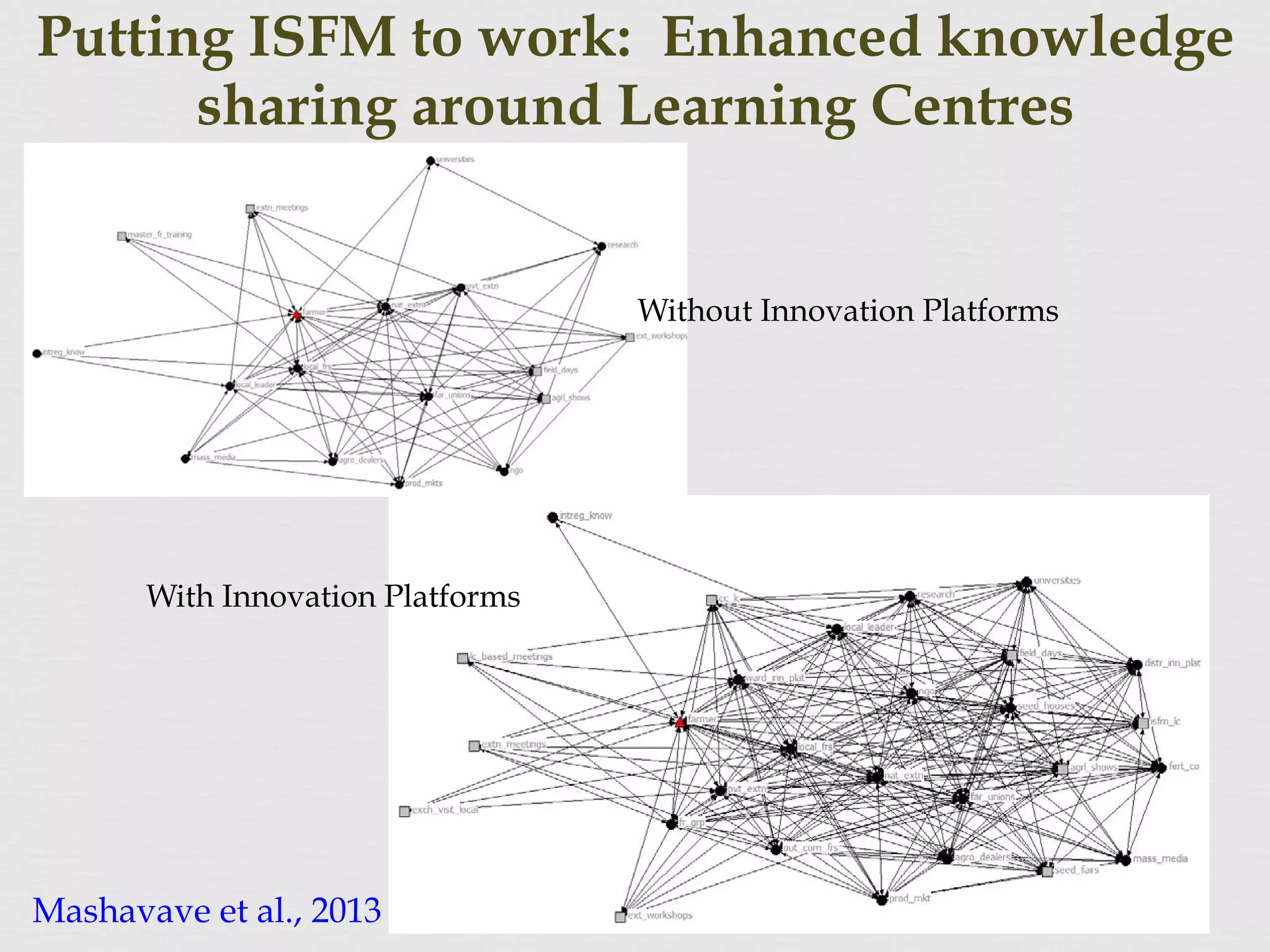

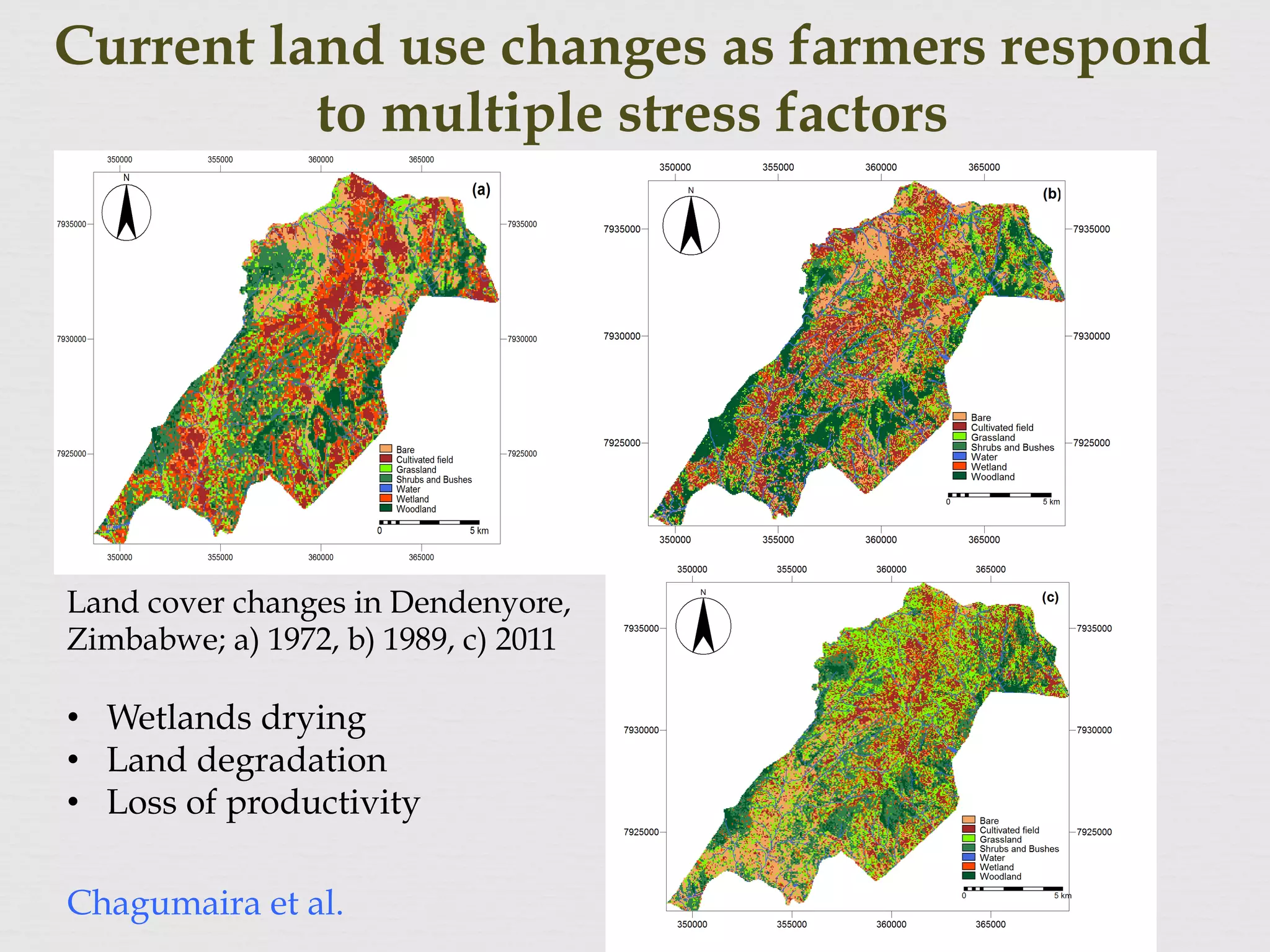

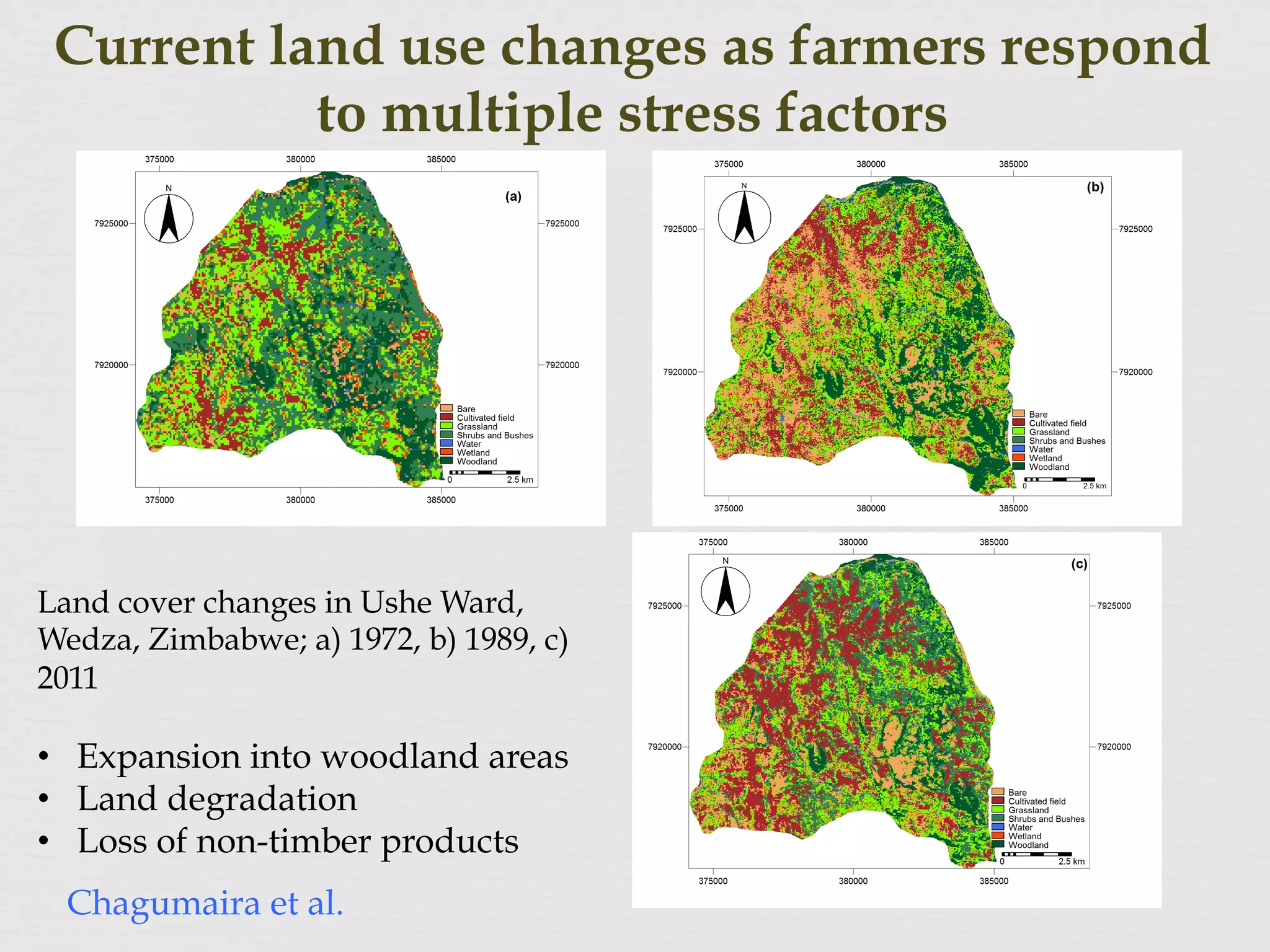

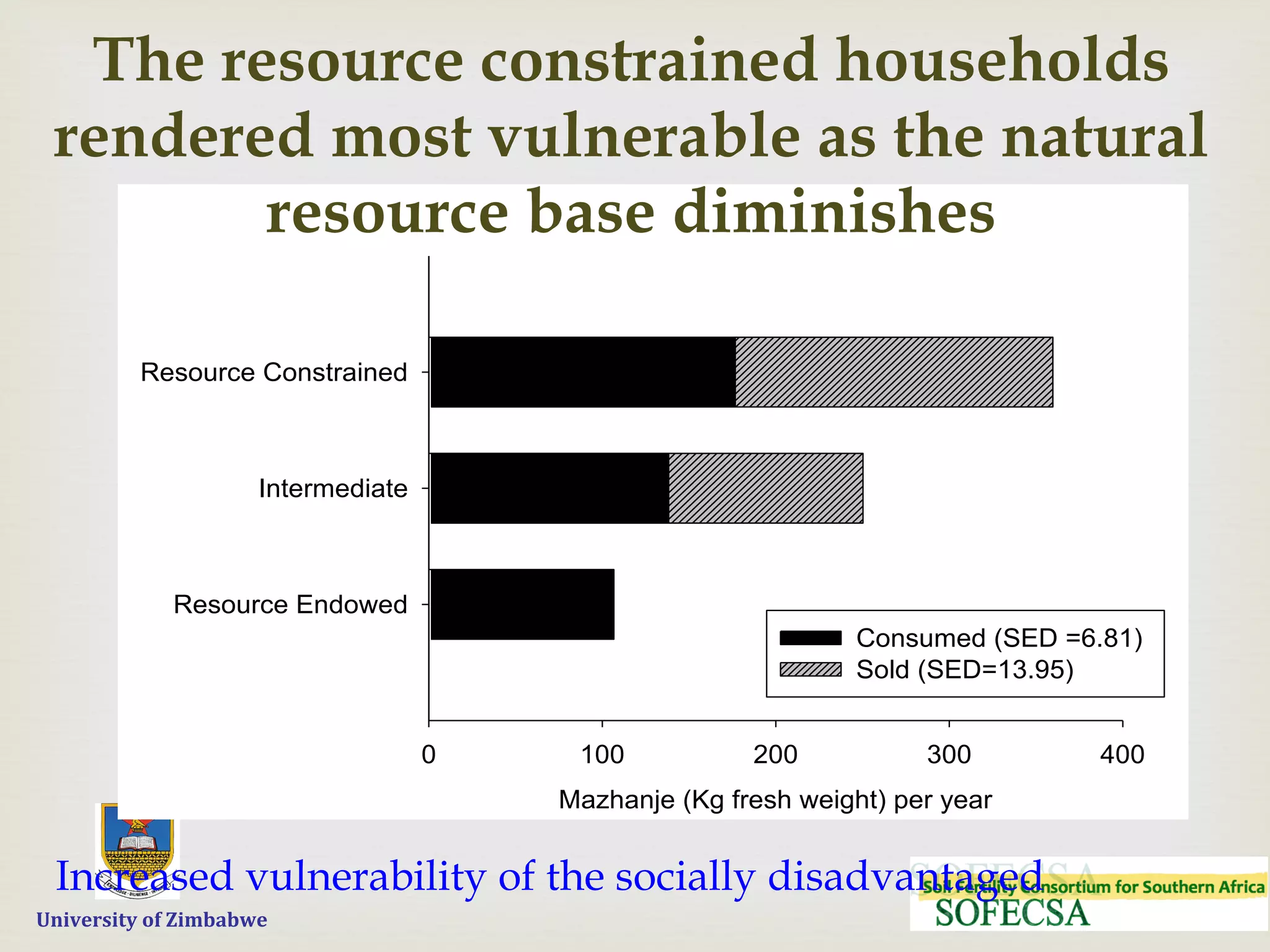

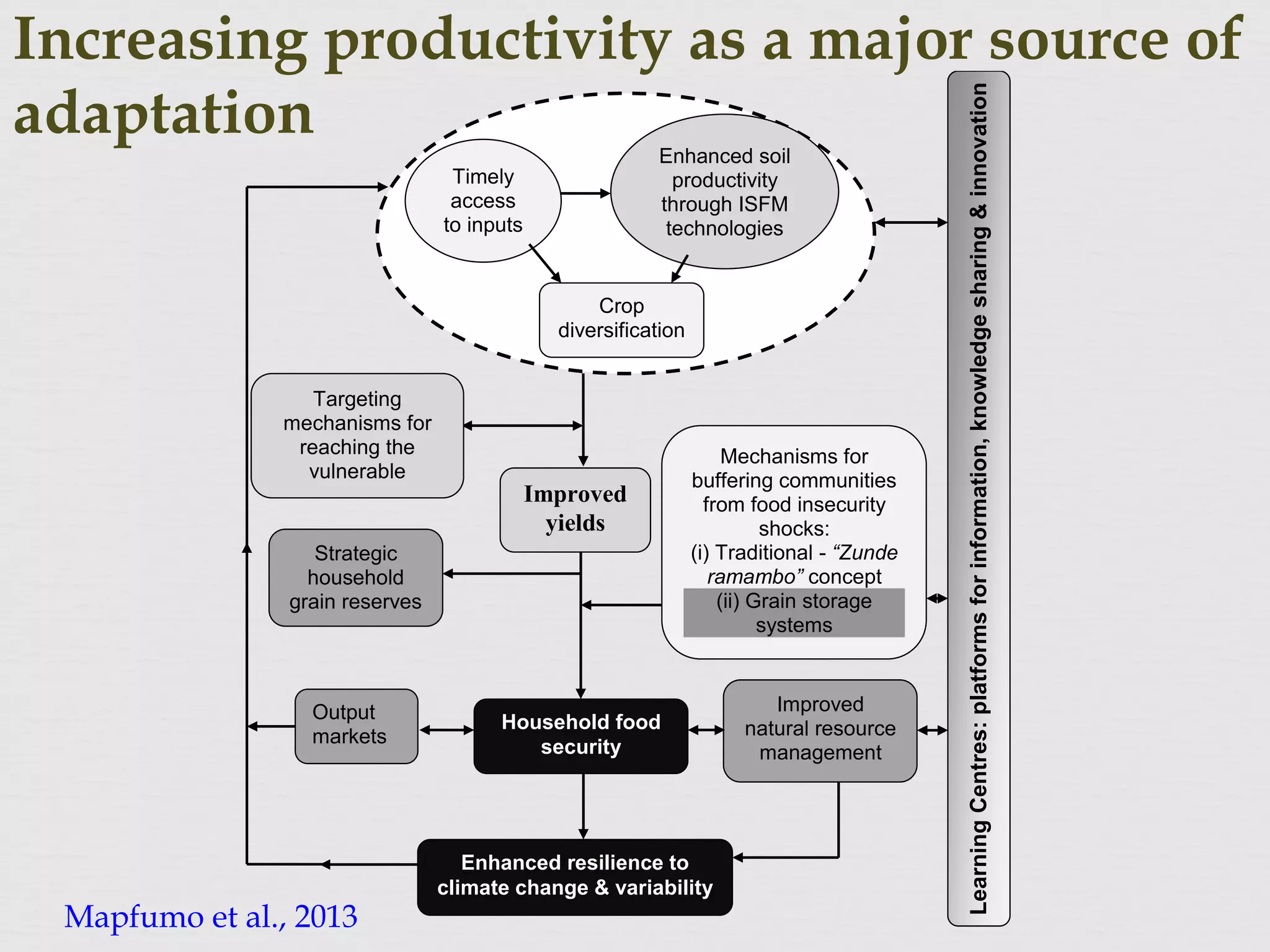

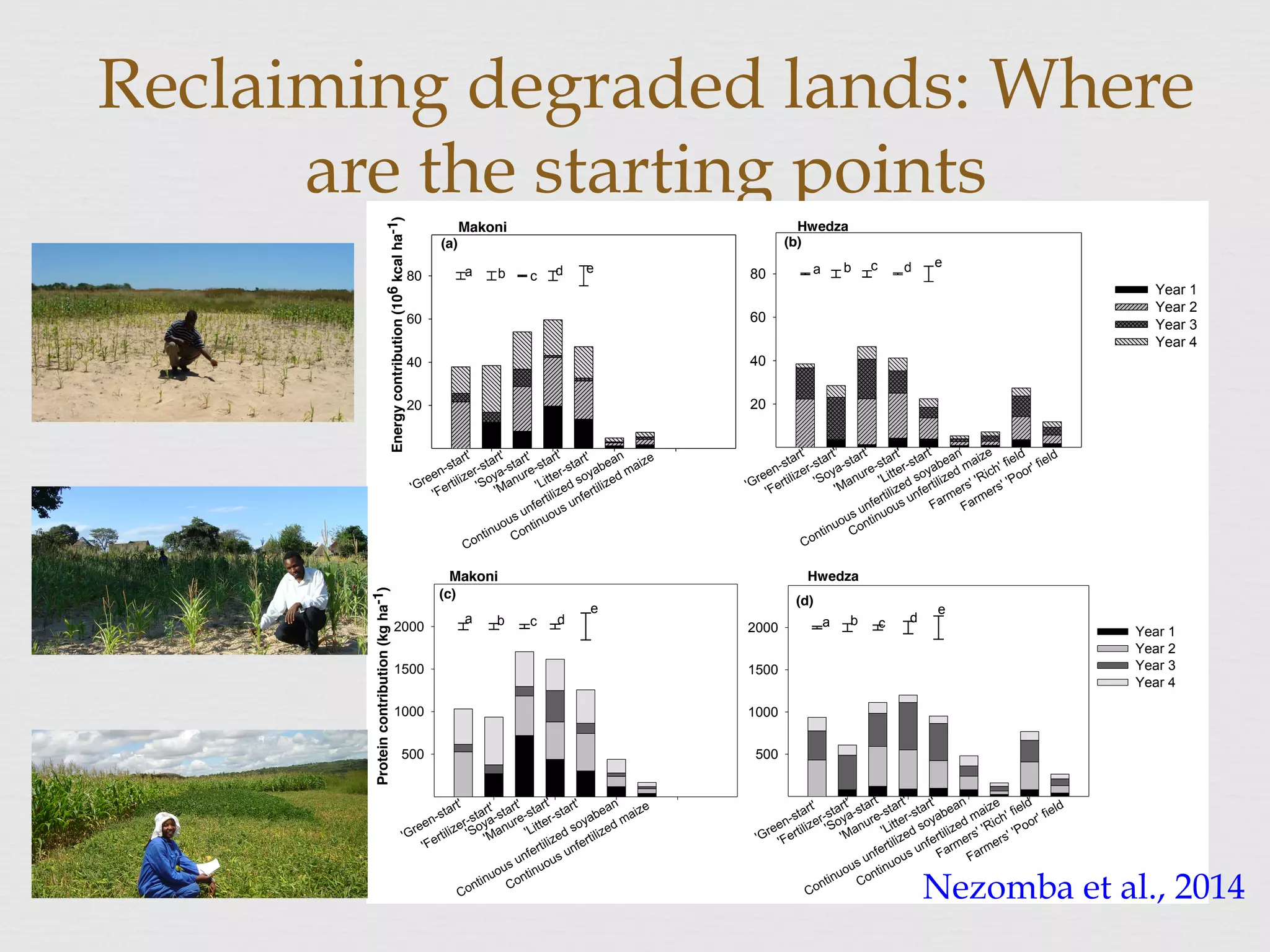

The document discusses the challenges of agricultural production in Africa, emphasizing the need for new farming paradigms in response to climate change, depleted natural resources, and food insecurity. It highlights the importance of conservation agriculture and integrated soil fertility management as strategies for enhancing productivity and resilience. The paper also notes the necessity of knowledge sharing among farmers and the adaptation of practices to local conditions for better agricultural outcomes.