Online Retailer Return Policies Impact Long-Term Customer Spending

- 1. Amanda B. Bower & James G. Maxham III Return Shipping Poiicies of Oniine Retailers: Normative Assumptions and the Long-Term Consequences of Fee and Free Returns To limit costs associated with product returns, some online retailers have instituted equity-based return shipping policies, requiring customers to pay to return products when retailers determine that customers are at fault. The authors compare the normative assumptions about customers that underlie equity-based return shipping policies with the more realistic, positivist expectations as predicted by attribution, equity, and regret theories. Two longitudinal field studies over four years using two surveys and actual customer spending data indicate that retailer confidence in those normative assumptions is unjustified. Contrary to retailer assumptions, neither the positive consequences of free returns nor the negative consequences of fee returns were reversed when customer perceptions of fairness were taken into account. Depending on the locus and extent of blame, customers who paid for their own return decreased their postreturn spending at that retailer 75%-100% by the end of two years. In contrast, returns that were free to the consumer resulted in postreturn customer spending that was 158%-457% of prereturn spending. The findings suggest that online retailers should either institute a policy of free product returns or, at a minimum, examine their customer data to determine their customers' responses to fee returns. Keywords: product returns, online retailing, regret, equity, customer spending Product returns are a widespread and expensive prob-lem. For example, product returns of consumer elec-tronics cost retailers and manufacturers almost $17 billion in 2011, representing a 21 % increase in returns since 2007 (Wolf 2012). Thus, many retailers have established return shipping policies intended to limit their own costs (e.g., Kandra 2000; Meyer 1999). A policy commonly insti-tuted by distant retailers (e.g., Amazon.com) is an equity-based return shipping policy: If the retailer determines that it is to blame for the return, the retailer absorbs the return's cost; otherwise, customers must pay those costs. While these retailers appear to assume that consumers' equity assess-ments are the only relevant reaction to return shipping costs (for a model of retailers' assumptions, see Figure 1), distant retailers' concern with the fairness is reasonable. "Fairness" refers to "rightness or deservingness" (Oliver 1997, p. 194) Amanda B. Bower is Professor of Business Administration/Marketing & Advertising, Williams School of Commerce, Economics, & Politics, Was-hington and Lee University (e-mail: bowera@wlu.edu). James G. Maxham III is Chesapeake & Potomac Telephone Company Professor of Commerce, University of Virginia (e-mail: maxham@virginia.edu). This research was funded in part by the Bernard A. Morin Fund for IVIarketing Excellence at the Mclntire School of Commerce. The authors thank Bill Ross, Ruth Bolton, Rick Netemeyer, David Mick, Amar Cheema, and research semi-nar participants at the University of Virginia, Penn State University, Georgetown University, and Peking University for helpful comments on earlier versions of this article. Robert Leone served as area editor for this article. based on a consideration of inputs and outcomes, and prior research has associated fairness perceptions with a positive effect on important postexchange customer reactions such as satisfaction, word of mouth, trust, commitment, and repurchase intentions (e.g., Maxham and Netemeyer 2003; Oliver and Swan 1989a, b; Swan and Oliver 1991; Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran 1998). We define "return shipping policy cost fairness" (cost fairness) as the extent to which customers believe the return shipping policy out-come (whether fee or free) is fair. Consistent with both prior work and the assumptions of equity-based return ship-ping policies, we expect that perceptions of return cost fair-ness are positively related to postreturn repurchases (see Figure 2). Research has yet to investigate how these return ship-ping policies and associated costs can influence customer evaluations and subsequent postreturn spending. In the pre-sent research, we identify the apparent, normative assump-tions underlying the equity-based return shipping policies of free return (i.e., the retailer absorbs the return shipping fee) versus a fee return (i.e., the customer pays the return shipping fee) and compare those assumptions with a posi-tivist perspective on consumers' psychological reactions and postreturn spending. Working with two leading online retailers, we coupled responses from two online surveys at key points over the course of customers' return experiences with the customers' 24-month prereturn and 24-month postreturn purchase histories. We find that consumer assess-ments of fairness and attributions are inconsistent with the © 2012, American Marketing Association iSSN: 0022-2429 (print), 1547-7185 (eiectronic) 110 Journal of Marketing Voiume 76 (September 2012), 110-124

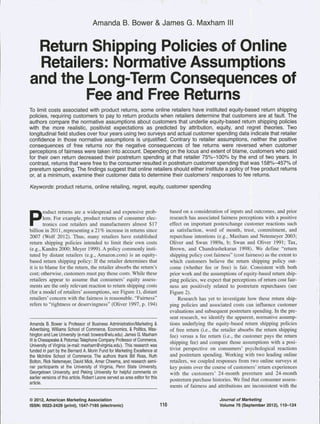

- 2. FIGURE 1 Model of the Normative Assumptions of the Product Returns Process Underlying Equity-Based Return Shipping Policies Product Failure Blame is eithe retailer or to self/consumer ^ rtO Attributed to Retailer Free Return Retailer's assessment No misapplication of j ^ ofbiame is consistent with the consumer's assessment Attributed to Self/Consumer return shipping policy Fee Return Equity Accomplished Consumers will perceive a return shipping policy as fair if the one to blame pays for the return, even if the consumer pays for it ^ / Postreturn ^ Spending i Equity is the only response to a return shipping policy that affects postreturn spending Notes: Explanations of assumptions underlying process model structure are in italics. FIGURE 2 Conceptual Model of Consumer Responses to Product Return Shipping Policies Retailer Attribution for Product Returns Return Shipping Policy (Free/Fee) ( 1 ' H2 Self-Attribution for Product Returns ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ - ~-^ Customer Perceptions of Cost Fairness — ^ ^ -^^ ) / H4 V J Customer Spending normative (and self-serving) assumptions of retailers. Not only do retailers overestimate tbe ameliorating (moderat-ing) effects of attributions on fee returns, but tbey also ignore consumers' affect stemming simply from return fees. In addition, free returns resulted in increases in postreturn spending (from preretum levels), and fee returns resulted in decreases in postreturn spending (from preretum levels), all regardless ofbiame attributions. Research on return policies is still developing. Botb Pastemack (2008) and Padmanabban and Png (1997) exam-ine manufacturer return sbipping policies offered to retail-ers. Otber research bas assessed actual consumer responses to return policies, suggesting the benefits to retailers of easy return policies. Anderson, Hansen, and Simester (2009) examine the value to consumers of the simple presence (vs. absence) of a return option and suggest a model retailers could use to optimize return policies. MoUenkopf et al. (2007) find that previous service experiences (e.g., return policies, web interface) could directly influence consumer loyalty intentions in the present product return context. Consistent with the present research, there is some research indicating that return policies instituted with the short-term gain in mind may have long-term negative con-sequences for tbe retailer. Despite retailer desire to control for "inappropriate" or "opportunistic" product returns with stricter return policies (Davis, Hagerty, and Gerstner 1998; Hess, Chu, and Gerstner 1996), Wood (2001) finds that lenient policies (manipulated in two of her studies as including free shipping) were associated with increased probability of ordering from the retailer, heightened ratings of product quality, and a reduction in overall purchase deci-sion conflict. Viewing the return process as part of a cycle, Petersen and Kumar (2009) find that while an increase in product returns results in a decrease in marketing communi-cations from the marketer toward that consumer, that same increase in returns will result in an increase in future cus- Return Shipping Policies of Online Retailers /111

- 3. tomer repurchases (up to a threshold). This research sug-gests the value in comparing the return policy assumptions that retailers make with actual consumer reactions. The Assumptions of Equity-Based Return Shipping Poiicies The implementation of an equity-based return shipping pol-icy is predicated on a variety of apparently implicit and nor-mative assumptions that lead distant retailers to believe such a policy would be both cost-effective and reasonable to customers. We consider those assumptions here and com-pare them with the customer reactions suggested by prior research. Assumption of Proportional Equity An assumption of equity-based return shipping policies is that consumers will perceive an exchange as fair if the out-comes they receive are proportional to the inputs they con-tribute, which translates into the "one to blame is the one to pay" philosophy (see Figure 1). Although this assumption is consistent with more traditional equity theories (e.g., Homans 1961), subsequent research suggests that people prefer advantageous or positive inequity (i.e., the equitable behavior that results in the maximization of one's own out-comes; e.g., Lapidus and Pinkerton 1995; Oliver 1997; Oliver and Swan 1989a). The customer view of advanta-geous inequity as "fairer" is prevalent in customer-retailer relationships (versus interpersonal). Customers may not see themselves as having equal responsibilities to the retailer in the exchange and may have more substantial expectations that the retailer bear much of the burden of the exchange (e.g.. Berger, Conner, and Fisek 1974; Lapidus and Pinker-ton 1995; Oliver 1997; Oliver and Swan 1989a, b). Consis-tent with prior research, we expect that customers receiving free returns will report significantly higher levels of cost fairness and have greater relative postretum repurchases than customers receiving fee returns, regardless of level of blame attribution (though we do expect blame attribution to moderate the extent of the effect, as discussed subsequently). Assumptions of Causal Attribution Dependence Retailers employing equity-based return shipping policies appear to assume that consumers' attribution of responsibil-ity for the return will be consistent with the retailers' (see Figure 1). Furthermore, retailers assume that these attribu-tions are negatively related so that as responsibility assigned to the consumer goes up, assignment to the retailer necessarily goes down. Called the "hydraulic assumption" in attribution theory, support for it means that causal agents for a given outcome should have "near perfect negative cor-relation between these judgments" (Bassili and Racine 1990, p. 882), "as if causal candidates competed with one another in a zero-sum game" (Nisbett and Ross 1980, p. 128). However, the hydraulic assumption of attributions has been largely disproven (e.g., Bassili and Racine 1990; Krull 2001; Miller, Smith, and Uleman 1981; Nisbett and Ross 1980; Taylor and Koivumaki 1976) because "internal and external [attributions] are not opposites on a single dimen-sion" (White 1991, p. 266). Solomon (1978) reviews research in which causal agents were measured separately (vs. on opposite ends of a single scale), concluding that the hydraulic assumption is "untenable." Similarly, Taylor and Koivumaki (1976) find when measuring the two separately that the correlation was -.14 (not significant [n.s.]). Therefore, in contrast to the assumptions underlying equity-based return shipping policies, a stronger attribution to the consumer may not necessarily result in a weaker attri-bution to the retailer (e.g., Johnson, Mullick, and Mulford 2002; Miller, Smith, and Uleman 1981). Although cus-tomers may attribute some product failures exclusively to the retailer, customers may instead attribute failure to them-selves, to neither party, or perhaps to both (e.g., Folkes 1984; Kelley, Hoffman, and Davis 1993; Oliver 1997; Weiner 2000; White 1991). In other words, we would expect that retailer and consumer self-attributions are independent, without a near-perfect negative relationship. Figure 2 pre-sents the separate conceptualization and relationships. Consequences of Inaccurate Assumptions in Attribution and Equity Assessments As a result of these assumptions, equity-based return ship-ping policies allow for only two possible pairs between attributions and applied return shipping policy: Retailers only pay when the return is their own fault, and consumers only pay when it is their own fault (see Figure 1). However, these policies do not take into account the reactions of con-sumers who are required to pay for a return for which they blame the retailer, nor do they allow for the possible bene-fits that might accrue when a consumer receives a free return when there is a stronger self-attribution. Put differ-ently, what happens when a consumer is "miscategorized" and disagrees with the retailer's assessment? There is a strong likelihood that consumers will dis-agree with retailer assignment of responsibility to the con-sumer (Oliver 1997). Consumers have a tendency to take more credit for positive outcomes and less blame for fail-ures, particularly in a marketing relationship (e.g., Oliver 1997; Valle and Wallendorf 1977). Given their preference for positive inequity, consumers tend to put particular emphasis on consumer outcomes and retailer inputs, result-ing in a disproportionate reaction to negative inequity (e.g., Oliver 1997; Walster, Berscheid, and Walster 1973). There-fore, the damage done to equity perceptions and postretum repurchases by a fee (vs. free; consumer outcomes) return will be disproportionately greater when consumers make stronger retailer attributions (vs. weaker; retailer inputs). Thus: Hj: Return shipping policy and retailer attributions interact such that customers who experience a fee (vs. free) return report disproportionately lower cost fairness and decrease spending when they indicate stronger retailer attributions than when they indicate weaker retailer attributions. There may also be positive effects of a "miscatego-rized" free return: a free return for which consumers strongly attribute the return to themselves. Thus, the pre-ferred state of positive inequity (e.g., Lapidus and Pinkerton 1995; Oliver 1997; Oliver and Swan 1989a) would be 112 / Journal of Marketing, September 2012

- 4. heightened when the customer receives a free retum when there are greater levels of self-attribution for the need for the product retum. Furthermore, under complaint condi-tions, Lapidus and Pinkerton (1995) find no evidence to support their hypothesis that consumers feel guilt or other unpleasant emotional states as a result of this type of posi-tive inequity. When assessing resentment stemming from a high/low outcome in an equitable/inequitable situation, they find that an interaction resulted largely from the dispropor-tionately low levels of resentment when participants experi-enced a positively inequitable situation. In other words, it is unlikely that there would be any negative emotional reac-tions (e.g., guilt) to negate or neutralize the positive reac-tions resulting from a free but "undeserved" return. Thus: H2: Return shipping policy and self-attributions interact such that customers who experience a free (vs. fee) return report disproportionately higher cost faimess and increase spending when consumers make stronger self-attributions than when they make weaker self-attributions. The Centrai Role of Regret on Consumer Responses Retailers employing equity-based return shipping policies clearly assume that fairness is the key response to the retum, expecting that postretum spending will be unaf-fected by retum shipping costs if the retum was "fair." However, consumers may have other, more dominant reac-tions to a fee or free retum shipping policy beyond the deservedness or fairness of retum costs. Specifically, regret refers to a negative feeling or "sense of sorrow" (Simonson 1992, p. 105) experienced in response to a negative out-come when a person compares his or her own actions to alternative behaviors and preferable outcomes (i.e., counter-factuals) that might have occurred instead (e.g., Zeelenberg, Van Dijk, and Manstead 1998). The opposite of regret is rejoicing or elation (e.g., Greenleaf 2004; Inman, Dyer, and Jia 1997; Landman 1987), which occurs when a person's choices lead to an outcome that is better than if other choices were made. Consumers are strongly motivated to avoid the emo-tional experience of regret, leading them to protect them-selves against it (e.g., Cooke, Meyvis, and Schwartz 2001; Greenleaf 2004; Inman and McAlister 1994). The simple anticipation of regret with regard to a future decision may result in inaction (i.e., nonpurchase; e.g., Landman 1987; Lemon, White, and Winer 2002; Simonson 1992; Tsiros and Mittal 2000). In contrast, an experience with rejoicing can lead people to make decisions that may involve riskier—but the hope of better—outcomes. For example, Greenleaf (2004) demonstrates that auction sellers experienced rejoic-ing because the winning price of an auction was higher due to the reserve price. These sellers subsequently set an even higher reserve price in a second auction, even though those higher reserve prices might decrease the chances of a suc-cessful second auction. Therefore, consistent with previous work, we expect regret to be negatively related to postretum repurchases (see Figure 2). Consumers may already experience a baseline level of regret stemming from the product failure and the need to retum the product (e.g., Oliver 1997). Of particular interest here is the effect that retum shipping costs may have on that baseline level of regret. Customers facing a fee retum will have an unrecoverable monetary cost due to retum shipping fees, in contrast to a nonpurchase from that retailer (Gilly and Gelb 1982). Comparison of this actual monetary loss to the nonpurchase altemative may heighten feelings of regret and, in particular, concems about future retum fees stem-ming from future purchases. Consistent with prior research, we expect that customers whose regret is further heightened by a fee retum will prevent the experience of future regret by reducing their purchases from the present distant retailer. Conversely, customers whose regret is lowered (i.e., greater levels of rejoicing) as a result of a free retum may increase postretum spending, willingly making riskier purchases. Thus (see Figure 2): H3: Compared with a baseline of regret stemming from the need to return the product, customers receiving free returns report significant decreases in that experienced regret, whereas customers receiving fee returns report sig-nificant increases in that experienced regret. While faimess and regret have appeared as constructs in the same study (e.g., Verhoef, Franses, and Hoekstra 2001; Vorhees, Brady, and Horowitz 2006), the relationship between the two remains to be addressed. As O'Shaugh-nessy and O'Shaughnessy (2005) indicate, regret theory has implications in equity considerations. We suggest that in addition to the regret heightened by retum costs, consumers might also experience heightened regret as a result of being treated in a manner they perceive as unfair. Xia, Monroe, and Cox (2004, p. 7) argue (but do not demonstrate) that if consumers believe a price to be unfair, they may choose to "leave the relationship, depending on their assessment of which action is most likely to restore equity" (for similar logic, see O'Shaughnessy and O'Shaughnessy 2005). Thus (see Figure 2): H4: Cost fairness is negatively related to regret, with regret partially or wholly mediating the relationship between cost faimess and postretum spending. iVIethods Study 1: Equity-Based Return Shipping Policies We conducted a longitudinal event field study over four years with a panel of online customers (average of 8.4 orders per year) who returned products to a leading e-commerce retailer of frequently purchased home, garden, and personal items. To qualify for the panel, customers needed at least 24 months of prereturn spending data. We gathered data at the following six time periods: (1) 24 months before the retum (i.e., 24 months prereturn [TO]), (2) 12 months leading up to the retum (i.e., 12 months preretum [Tl]), (3) time of retum (i.e., retum [T2]), (4) soon after the retailer handled the retum (i.e., postretum [T3]), (5) 12 months after the retum (i.e., 12 months postretum [T4]), and (6) 24 months after the retum (i.e., 24 months postretum [T5]). The T2 data were collected during approximately the same month. Thus, all customers shared approximately the same T0-T5 period. Return Shipping Policies of Oniine Retailers /113

- 5. and we had data from 24 months before and after the retum for each respondent. 12 and 24 months preretum (TO, Tl). We collected yearly prereturn purchasing history for the 24 months before the return for the 334 respondents who completed the T2 and T3 surveys. These data included the number of orders placed, the dollar value of the orders, and the product descriptions. We accounted for inflation in dollar variables using the seasonally adjusted Consumer Price Indexes. Return (T2). At the time of retum, 500 customers either telephoned the retailer or initiated a retum using the form enclosed in their order, triggering the T2 online question-naire link to be e-mailed. Customers were offered a $25 gift certificate to complete the two surveys (T2 and T3). (Only 39% of respondents in Study 1 redeemed the gift certificate, and there were no significant differences in redemption rates across fee and free conditions [p > .50].) Of the 500 surveys sent, 351 customers completed usable surveys, rep-resenting a 70% response rate. The T2 survey first asked customers to indicate the details of their retum (i.e., product numbers, whether the items were purchased as gifts, reason for returning, prepurchase awareness of the return shipping policy, and whether they wanted a refund or exchange). Customers completed questions regarding situational pur-chase involvement, regret, attributions toward the retailer, and self-attributions, and all items were measured on a seven-point scale. We adapted to this study a three-item semantic differential involvement measure from prior research (Ratchford 1987) to measure whether the purchase of the product was highly involving. A three-item retailer attribution measure asked respondents to indicate the extent to which the retailer was responsible for the letum, while a separate three-item self-attribution measure assessed self-attribution. We adapted a measure from Tsiros and Mittal (2000) to measure customer perceptions of regret. Finally, respondents provided demographic and buyer profile infor-mation (see the Appendix). Postretum (T3). After the completion of the return process (refund or receipt of a product exchange), a second survey link was e-mailed to the 351 respondents who com-pleted the T2 survey. Of those, 334 customers completed usable surveys, representing a 95% response rate for T3 and an overall 67% response rate. The sample had the following demographic characteristics: 58% of the respondents were female, 66% were 36-55 years of age, 75% held college degrees, and 89% reported that they retum less than 20% of their online purchases. In addition, this was the first product retum for all customers to this retailer, creating a baseline for accurately tracking customer perceptions regarding their first retum experience with the focal retailer. The T3 survey assessed customer perceptions of regret and cost faimess measures adapted from prior research (Smith, Bolton, and Wagner 1999; Tax, Brown, and Chandrashekaran 1998). 12 and 24 months postretum (T4, T5). We collected two years of postretum purchasing history for the 334 respon-dents, including the number of orders placed, dollar value of the orders, and product descriptions. None of our respon-dents retumed the purchases made 24 months after their ini-tial retum, and the postretum customer spending variables exclude the monetary value of the focal product retum as well as the $25 gift certificate value. Return shipping policy outcome. Fifty-three percent of respondents received a free return. Consistent with an equity-based retum shipping policy, a retum manager used customer self-report as an input in making "fair" judgments regarding blame and allocation of retum shipping costs. In general, the retailer in Study 1 assigned a fee retum when customers indicated one of the following reasons for the retum: (1) the item did not fit, (2) the item was too expen-sive, (3) the color did not match, (4) gift recipients did not want/need, (5) the item did not fit with other components, or (6) the customers changed their minds. The retailer offered a free retum when customers returned an item for the following reasons: (1) the item was damaged in transit, (2) the item was defective, or (3) the company shipped the wrong item. Contextual variables. We gathered potential covariates both from the surveys and the retailer database. These covariates include product involvement, the dollar amount of shipping costs to retum the product (regardless of fee or free policy), the number of days to resolve the return, the number of days that passed after receiving the product before the retum was initiated, the length of the customers' relationship with the retailer (measured at 24 months pre-retum), the dollar amount of the order, and the dollar amount of the retumed items. Study 2: Generalizing Beyond Equity-Based Return Shipping Policies To rule out that cost faimess and regret reactions are due to the type of retum shipping policy (i.e., equity based), we conducted a second longitudinal field study over the same 49-month period with an electronics retailer that used a dif-ferent retum shipping policy. The retailer categorized prod-ucts as qualifying for free or fee returns according to the gross margins, warning consumers before purchase (even requiring them to click a box noting their understanding) whether a retumed product would be subject to shipping charges regardless of blame. Customers who were reim-bursed were categorized as "free" (n = 682, 53), and those who were not reimbursed were categorized as "fee" (n = 614). Thirty-six percent of the retums were because cus-tomers changed their minds; 27% were due to problems with item descriptions, installation, or instructions; and 37% were due to quality problems. Customers place an average of 12.6 orders per year with the retailer. The data collection procedures and measures for the electronics sam-ple mirrored those employed in the first study. Of the 2750 surveys sent at the time of retum (T2), 1623 customers completed usable surveys, representing a 59% response rate. After the retailer handled the retum, 1296 customers completed and submitted a usable T3 survey (an 80% response rate for T3). We collected 24 months of pre- and postretum purchasing history for each of our 1296 respon-dents and queried the retailer's database to collect the same contextual variables collected in the first study. Our response rate from the initial mailing of the first T2 ques- 114/Journal of Marketing, September 2012

- 6. tionnaire to the completion of the T3 questionnaire was 47%. Customers were offered a $25 gift certificate to com-plete the T2 and T3 surveys. (Only 23% of respondents in Study 2 redeemed the gift certificate, and there were no sig-nificant differences in redemption rates across fee and free conditions ¡p > .10].) The sample exhibited the following demographic characteristics: 48% were female, 36% were 36-55 years of age, and 62% held college degrees. In addi-tion, the product return in this study represented the first return recorded by the retailer for each respondent, allowing for accurate tracking of customer perceptions regarding their first return experience with the focal retailer. Across both studies at both the prereturn 12- and 24- month marks, we found no significant differences among the free and fee groups in prereturn purchase rates, order values, or value of returned products, nor were there signifi-cant differences in the dollar amount of return shipping across levels of attributions to retailer (all p> .10). Confir-matory factor models indicated that our measures are psy-chometrically sound in both studies regarding model fit, discriminant validity, and internal consistency (see the Appendix). Checiis for Respondent and Measure Bias To check for sample and nonresponse biases in each sample using customer profile information in each of the retailers' databases, we compared the demographic and buying pro-files in our samples with three other customer groups: (1) customers who returned products during our studies but did not participate in the studies (i.e., nonparticipants; Study 1: n - 285; Study 2: n = 1545), (2) customers who returned products before our studies and did not receive our survey (i.e., nonsurveyed returners; Study 1: n = 567; Study 2: n = 1780), and (3) customers who have never returned products to the focal retailers (i.e., nonreturners; Study 1: n = 462; Study 2: n = 1378). There were no significant differences regarding the length of relationship with the retailers, age, total number of purchases, or average order value between the three other customer groups and our samples (/? > .10), and they were similar across gender, income, and education. Likewise, the reasons for returning and the retailer's prod-uct return strategies were similar across groups. Other data collection and analysis indicated that the three control groups in each sample did not differ significantly from our respondents' in customer spending {p > .10). In addition, nonparticipants and nonsurveyed returners who did not pay for return shipping significantly increased their customer spending over the next two years, while nonparticipants and nonsurveyed returners who paid for return shipping costs significantly decreased their customer spending over the next two years (i.e., a negative in customer spending; p < .01). Nonparticipants and nonsurveyed returners with free returns repurchased at significantly higher rates than nonre-turners, and nonparticipants and nonsurveyed returners with fee returns repurchased at significantly lower rates than nonreturners {p < .01). Overall, these data checks suggest that potential response and nonresponse biases in ratings are minimal. Resuits The Roie of Attributions in Cost Fairness and Customer Spending We argue that the postreturn spending among customers receiving a free return significantly increases from prereturn spending, while the postreturn spending among customers paying a fee return significantly decreases from prereturn spending levels. Instead of simply examining the effects of return shipping policies on changes in spending at the end of the 24-month postreturn period, we examined the effects at both the 12-month and 24-month postreturn points. Our longitudinal research design enables us to determine whether any changes in spending results in shorter-term effects (e.g., limited to 12 months but rebounding to prereturn levels by 24) or longer-term trends of postreturn spending. Initial analyses contradicted some of the retailer assumptions underlying equity-based return shipping poli-cies. The correlations between retailer attributions and self-attributions, though significant in both studies, are not "per-fect" (Study 1: (|) = -.17; Study 2: ^ = -.14). This indicates that attributions are empirically distinct (Fornell and Lar-cker 1981) and should be measured separately. Evidence also contradicts the assumption that retailer assignments of responsibility are consistent with consumer assignments. Considering only Study l's results because of the retailer's equity-based return shipping policy, customers making stronger attributions to the retailer were required to pay return shipping fees (n = 73; 46%) almost as frequently as those who received a free return (n = 86; 54%), regardless of self-attributions. Taking into account self-attributions, among those customers who would meet the retailer's own standards for a free return (i.e., stronger retailer attributions/ weaker self-attributions; n = 81), 43% were required to pay a fee. Similarly, among those customers who would meet the retailer's standards for a fee return (i.e., weaker retailer attributions/stronger self-attributions; n = 105), 50% received a free return. Similar proportions exist in Study 2, in which return fee responsibility is unrelated to equity decisions and instead is determined by the type of product purchased. In other words, equity-based determinations of responsibility were as consistent with customer judgments as determina-tions entirely unrelated to assessments of equity decisions. To test H] and H2, we estimated a repeated measures general linear model with one categorical between-subjects factor (return shipping policy outcome: free and fee), two continuous between-subjects factors (retailer attributions and self-attributions), one between-subjects dependent variable (cost fairness), and one within-subject dependent variable captured across four time intervals (customer spending: TO, Tl, T4, and T5). We also modeled six covari-ates: involvement, the dollar amount of return shipping costs, the number of days to resolve the product return, the number of days that passed after receiving the product before the return was initiated, the length of the customers' relationship with the retailer, and the order dollar amount. Last, we included consumers' prepurchase awareness of return shipping policy as a two-level blocking factor (i.e., yes or no). Return Shipping Policies of Online Retailers /115

- 7. Return shipping policy awareness was significantly related to cost faimess (Study 1: F(l, 319) = 22.96,/? < .01, ri2 = .07; Study 2: F(l, 1281) = 57.62,p < .01,ri2 = .04) and customer spending (Study 1: F(l, 319) = 38.78,p < .01,ri2 = .11; Study 2: F(l, 1281) = 10.41,^1 < .01, rjZ = .01), and therefore we retained it in the model (all other covariates were nonsignificant and thus were eliminated). Across botb studies, the two-way interaction (shipping policy x retailer attribution) was significant for cost faimess (Study 1 : ß = -.53, t(325) = 2.95,/? < .01, -pZ = .03; Study 2: ß = -.623, t(l,287) := 4.60,p < .01, r|2 = .02). Likewise, the shipping policy X retailer attribution was significant for customer spending at both T4 (Study 1: ßT4 = 416.50, t(325) = 4.38, ri2 = .06; Study 2: ßx4 = 1519.97, t(l,287) = 8.54, ri2 = .05, p < .01) and T5 (Study 1: ßxs = 765.39, t(325) = 6.00, ^^ = .10; Study 2: ^5 = 3026.40, t(l,287) = 11.96, ri2 = .10,p < .01). To explore Hj, we examined the slopes of retailer attri-bution across fee and free retum shipping policies. Next, we conducted a spotlight analysis (Fitzsimmons 2008; Irwin and McClelland 2001) at one standard deviation above the mean of retailer attribution (i.e., stronger retailer attributions) and one standard deviation below the mean of retailer attribu-tion (i.e., weaker retailer attributions) to explore the details of the interaction. As we hypothesize, and as we show in Figure 3, the drop in cost faimess from a free to a fee retum was greater when customers more strongly blamed the firm than when they expressed weaker retailer attributions (Study 1: ß = .76, t(330) = 8.26; Study 2: ß = .82, t(l ,292) = 9.36, p < .01). Yet the drop in customer spending from a FIGURE 3 Effects of Return Shipping Policy A: Effects of Return Shipping Policy and Retailer Attributions on Cost Fairness 6.00 5.00 8 4.00 J E ¡2 3.00 -i o 2.00 -j 1.00 j 0 4 5.20 •l.SO 3.16 4.93 3.60 2.46 Free Return Shipping Fee Return Shipping Study 1 • Weaker retailer attribution I I Stronger retailer attribution Free Return Fee Return Shipping Shipping Study 2 B: Effects of Return Shipping Policy and Self-Attributions on Cost Fairness 5.68 5.60 3.24 2 30 Free Return Fee Return Shipping Shipping Study 1 I Weaker self-attribution I Stronger self-attribution Free Return Fee Return Shipping Shipping Study 2 Notes: Means for retailer attributions and self-attributions occur at one standard deviation below the grand mean (weaker) and one standard deviation above the grand mean (stronger). 116 / Journal of Marketing, September 2012

- 8. free to a fee retum was more precipitous when customers expressed weaker retailer attributions than when they more strongly blamed the firm (Study 1: ß = 734.93, t(330) = 10.03,p < .01; Study 2: ß = 954.83, t(l,292) = 12.44,p < .01). As such. Hi is partially supported (see Figure 4). Regarding H2, the two-way interaction (shipping policy x self-attribution) was significant in both studies for cost fair-ness (Study 1: ß = -.392, t(325) = -2.19, p < .01, Ti2 = .02; Study 2: ß = -.615, t(l,287) = 4.60, p < .01, Ti2 = .02). In Study 1, the retum shipping policy x self-attribution inter- FIGURE 4 Retailer Attributions and Changes in Customer Spending A: Study 1 $1,400.00 $1,200.00 $1,000.00 $800.00 $600.00 $400.00 $200.00 $838.15 $177.43^ 0'' $621.42 $235.36 »... $1,258.57 ^ „ . ^ $743.97 $109.54 -Ti $59.52 Free and weaker retailer attributions Fee and weaker retaiier attributions • Free and stronger retailer attributions • Fee and stronger retailer attributions 24 Months Prereturn 12 Months Prereturn 12 Months Postretum 24 Months Postretum B: Study 2 $6,000.00 $5,000.00 $4,000.00 $3,000.00 $2,000.00 $1,000.00 y' .•'$3,363.97 . -" '"'^ $1,964.04 .. $447.53 ! 7 * 111 1 ^ ^ _ $77.34 $5,013.05 $2,496.13 1 $0.00 Free and weaker retailer attributions Fee and weaker retailer attributions Free and stronger retailer attributions Fee and stronger retailer attributions 24 Months Prereturn 12 Months Prereturn 12 Months Postretum 24 Months Postreturn Notes: The means for weaker attributions are one standard deviation below the grand mean, and the means for stronger attributions are one standard deviation above the grand mean. Return Shipping Policies of Online Retaiiers /117

- 9. action was not significant for customer spending at both T4 (ßx4 = 147.46, t(325) =: 1.52, n.s.) and T5 (ßxs = 44.10, t(325) = .34, n.s.). Yet the interaction was significant in Study 2 at both T4 (PT4 = 497.49, t(l ,287) = 2.70, ^^ = .01) and T5 (ßx5 = 679.24, t(l,287) = 2.59, ri2 = .01,p < .01). We con-ducted a spotlight analysis at one standard deviation above the mean of self-attribution (i.e., stronger self-attributions) and one standard deviation below the mean of self-attribution (i.e., weaker self-attributions) to explore the details of the interaction. As we hypothesized, the drop in cost faimess from a free to a fee retum was more precipitous when cus-tomers more strongly blamed themselves than when they expressed weaker self-attributions (Study 1: ß = .182, t(330) = 7.43,p < .01; Study 2: ß = .741, t(l,292) = 9.34,p < .01; see Figure 3). Similarly, in Study 2, the drop in cus-tomer spending from a free to a fee retum was more precip-itous when customers more strongly blamed themselves than when they expressed weaker self-attributions (ß = .985, t( 1,292) = 11.93, p < .01). Yet the spotlight analysis was not significant in Study 1. Consistent with H2, cus-tomers in both studies who experienced a free return reported disproportionately higher cost faimess when they made stronger self-attributions than when they made weaker self-attributions (see Figure 3). In addition, cus-tomers in Study 2 who experienced a free return reported disproportionately higher increased spending when they made stronger self-attributions than when they made weaker self-attributions (see Figure 5). Thus, H2 is sup-ported in Study 2 and partially supported in Study 1. Regret To test H3, we estimated another repeated measures general linear model with one within-subject factor (time: T2 and T3), one between-subjects factor (retum shipping policy outcome: free and fee), one dependent variable (regret), the six previously used covariates, and two additional covariates (retailer attributions and self-attributions). In Study 1, retailer attributions, self-attributions, and retum shipping policy awareness were significantly related to regret (retailer: F( 1, 323) = 70.63,p< .01,112= .18; self: F(l, 323) = 5.00,p < .03, ri2 = .02; awareness: F(l, 323) = 46.92, /? < .01, r|2 = .13). Likewise, in Study 2, retailer attributions, self-attribu-tions, and retum shipping policy awareness were signifi-cantly related to regret (retailer: F(l, 1285) = 339.28, p < .01, ri2 = .21; self: F(l, 1285) = 4.68, p < .03, ri2 = .01; awareness: F(l, 1285) = 167.46,;? < .01,ri2 = .12; all other covariates were nonsignificant and eliminated). Consistent with H3, customers receiving free retums reported signifi-cant decreases in postreturn regret from initial retum levels, whereas customers receiving fee retums reported signifi-cant increases in postretum regret from initial retum levels (Study 1: F(l, 329) = 206.16, p < .0l,r2= .39; Study 2: F(l, 1,291) = 661.39,p < .01,ri2 = .34; see Figure 6.) Effects of Fairness and Regret on Long-Term Customer Spending One of the assumptions underlying equity-based return shipping policies and/or our expectations is the positive relationship between faimess (as per retailer and our expec-tations) and customer spending, as well as the negative rela-tionship between regret and customer spending. To assess these assumptions, we first estimated longitudinal structural models to assess the relationships of cost faimess and regret on customer spending over time, as well as to note the amount of variance explained in customer spending over time. To test H4, we examined whether regret (T3) mediates the relationship between cost faimess (T2) and customer spending (TO, Tl, T4, T5) in a manner consistent with Baron and Kenny (1986). We examined four conditions for mediation using structural equation modeling. The first con-dition is satisfied if cost fairness affects the mediator (regret). The second condition is satisfied if regret affects the dependent variable (customer spending). We estimated a mediated structural equation model testing the direct paths from cost faimess —> regret —> customer spending. Both these conditions were met, as this model yielded marginal fit (Study 1:%^= 120.54,p < .01 ; comparative fit index (CFI) = .97; Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) - .95; and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .15; Study 2: ^2 = 371.18,p < .01; CFI = .96; TLI = .94; and RMSEA = .14). Moreover, the completely standardized exogenous path from cost faimess to regret (Study :j = -.73; Study 2:7 = -.65) and the endogenous path from regret to customer spending (Study 1: ß = .70; Study 2: ß = .74) were both sig-nificant {p < .01). The third condition is satisfied if cost faimess has a direct effect on customer spending. Thus, we estimated a direct model with only one direct path from cost faimess to customer spending. The model fit the data well (Study 1: ^2 = .56,p = .75; CFI = .99; TLI = .99; and RMSEA = .01 ; Study 2: %2 = 14.63,p < .01; CFI = .99; TLI = .99; and RMSEA = .07), and the completely standardized path was significant (Study 1: 7= .60; Study 2: y = .51,p < .01), satisfying the third mediating condition. The fourth mediating condition is satisfied if the direct path from cost faimess to customer spending becomes non-significant (i.e., full mediation) or reduced (partial media-tion) when we included the mediated paths from cost fair-ness -^ regret -^ customer spending in a full model (i.e., the mediated model). The fit of the mediated model was better than the fit of the full model with the added exoge-nous path from cost faimess to customer spending (Study 1: 5C2^iff = 107.33; Study 2: x^diff = 333.51; d.f. - l,p < .01). Moreover, the completely standardized path estimate between cost fairness and customer spending became non-significant (Study 1: 7= .02; Study 2: 7= .04,p > .10), indi-cating that regret fully mediates the effect of cost faimess on customer spending. Moreover, the amount of variance explained in customer spending was greater for the medi-ated model (Study 1: R2 = .78; Study 2: R2 = .74) than for the full (Study 1: R2 = .63; Study 2: R2 =: .61) or direct (Study 1: R2 = .45; Study 2: R2 = .34) models, suggesting that cost faimess is a better predictor of customer spending when modeled as an indirect effect through regret. In sum-mary, regret mediates the effect of cost fairness on customer spending, in support of H4 in both studies. To provide context to our findings, we conducted sev-eral multigroup nested models in accordance with Neff 118 / Journal of Marketing, September 2012

- 10. FIGURE 5 Self-Attributions and Changes in Customer Spending A: Study 1 $1,200.00 $1,000.00 $800.00 $600.00 $400.00 $200.00 • • Free and weaker self-attributions • • Fee and weaker self-attributions Free and stronger self-attributions Fee and stronger self-attributions 24 Months Frereturn 12 Months Frereturn 12 Months Fostreturn 24 Months Fostreturn B: Study 2 $4,000.00 $3,500.00 $3,000.00 $2,500.00 $2,000.00 $1,500.00 $1,000.00 $500.00 m. ii.iii.iiii $3,787.55 $2,703.98 ,.-¡/^ / ^ $2,624.03 / "$298.79 $286.17 Ti».,,..^^ ~"~-—„.,,^125^ $3,721.63 $45.58 Free and weaker self-attributions Fee and weaker self-attributions • Free and stronger self-attributions • Fee and stronger self-attributions 24 Months Frereturn 12 Months Frereturn 12 Months Postretum 24 Months Postretum Notes: The means for weaker attributions are one standard deviation below the grand mean, and the means for stronger attributions are one standard deviation above the grand mean. (1985) to examine whether the modeled parameter esti-mates varied significantly across eight relevant customer groups: 2 (retailer attributions: weaker and stronger) x 2 (self-attributions: weaker and stronger) x 2 (retum shipping policy: free and fee). The chi-square tests across all nested models indicated that the parameter estimates were stable Return Shipping Policies of Online Retailers /119

- 11. FIGURE 6 Changes in Regret over Time A: Study 1 4.53 3.48 o Q. UJ perienced Regret X u 0- 6- 5- 4- 3- 2- 1 - 0- Time of Return •—' Free return 4.55 « ^ 3.48 —B Time of Return " " • • Free return (T2) shipping •"• B: Study — " 1,1— (T2) shipping •— Postreturn (T3) •• Fee return shipping 2 mmmmma^«....^ - - — Postreturn (T3) "» Fee return shipping Notes: iVIeans for retailer attributions and self-attributions occur at one standard deviation below the grand mean (weaker) and one standard deviation above the grand mean (stronger). (i.e., not significantly different) across the eight subgroups {p > .10), enhancing the predictive validity of the overall model. Discussion Contrary to economic research suggesting that retailers should toughen online return shipping policies, our studies suggest that such strategies might be shortsighted and that retailers should carefully consider how return shipping poli-cies affect revenues. We conducted two event field studies simultaneously over approximately 49 months to assess the psychological and behavioral reactions of customers to equity-based return shipping policies. Our expectations, as refiected in Figure 2, were supported, indicating that retail-ers' normative expectations (refiected in Figure 1) are largely inconsistent with consumer responses. Contrary to retailer assumptions, the actual return shipping policy cus-tomers received (whether free or fee) largely determined their postreturn spending regardless of attributions and cost fairness. Both studies suggest that customers paying for their own product returns will universally decrease their repurchases and that those receiving free returns will uni-versally increase their repurchases. In other words, the pri-mary conclusion for retailers from the present research is that in the interest of increased sales, it is beneficial to insti-tute a free return shipping policy. At the very least, our work is a call to online retailers to consult their own propri-etary customer data to determine any effects of return ship-ping costs on customer relationships and purchases. The Dangers of Fee Return This recommendation has the potential to elicit concerns from retailers. Retailers have short-term motivations for controlling return costs. As such, they may require cus-tomers to absorb return shipping policies, so they can avoid those costs themselves, or even induce consumers to keep products they might otherwise return to maintain the profits from the sale. Retailers may also be concerned with limiting abusive returns. However, while retailers may be in control of determining who pays for the return shipping costs, our findings remind retailers that customers will have their own independent perceptions of blame, affective reactions to return fees, and, most importantly, ability to decide whether they will repurchase from the retailer. Depending on attri-bution condition, fee returns universally resulted in a decrease in spending, ranging from 74.84% to 100% (see Figures 4 and 5). Our findings strongly contradict the assumptions made by retailers that attempt to control or limit their own costs by instituting equity-based return shipping policies. First, retailers are particularly ineffective at categorizing blame in a manner consistent with consumer perceptions. While a properly executed equity-based return shipping policy should have all retailer-blaming customers receiving free returns, the retailer in Study 1 (which used such a policy) assigned those customers free and fee returns in approxi-mately equal proportions. Similarly, we found that the retailer in Study 1 (which assigned fee returns using an equity-based return shipping policy) was approximately as consistent in assigning responsibility for the return to con-sumers who held themselves and not the retailer responsible as the retailer in Study 2, which used an entirely different policy for assigning return fees. Even if retailers made attributions of blame consistent with customer perceptions, the consequences of fee returns for retailers are still negative and profound. In a "perfect" fee condition, in which consumers strongly blame them-selves and hold weak attributions to the retailer, consumers in Study 1 (in which the retailer used an equity-based return shipping policy) still decreased their spending by 88%, and those in Study 2 decreased their spending by 93%. We found that customers appear to prefer advantageous or posi-tive inequity, perceiving free returns to be fairer than fee returns. In sharp contrast to the expectations of retailers, the dominant effect of the valence of the return shipping policy (fee/free) is not overcome by any combination of attribution conditions. One key reason for this result is that, contrary to the expectations of retailers, the dominant response to product return shipping policies is not equity but rather regret. Cus- 120 / Journal of Marketing, September 2012

- 12. tomers' negative emotions and sorrow related to retum costs are the primary driver of postretum shipping and, indeed, entirely explain equity's effect on postretum repur-chases. Therefore, while equity played a role in postretum spending, we found that it was only through customers' feelings of regret. Retailers may not be able to rely on the type of retum shipping policies to cue consumer reactions to the policies. Our research suggests that the type of retum shipping policy heuristic used to determine the policy application (whether equity-based or dependent on the type of product being retumed) is largely irrelevant to how customers might react to a fee or free outcome. Even though the two retailers in our studies had two different metrics for determining whether the customer received the fee or free retum shipping out-come, one equity-based and one product-based, the conclu-sions across both studies were (except for self-attribution findings) similar. This finding suggests that cost faimess considerations play a smaller role than regret in shaping consumers' future repurchase decisions. Retailers must also realize that consumers may not wam a retailer if a fee return will result in a decrease in future repurchases. The retailers in both our studies received no formal complaints from fee returns, with these customers quietly decreasing repurchases (and, in some cases, sharply). While retailers implementing an equity-based retum shipping policy may perceive the dearth of com-plaints among fee retumers as support for such a policy, analysis of the longer-term consequences of fee retums sug-gests that a preferable option from a customer loyalty per-spective is to simply offer all customers a free retum. The Benefits of Free Returns Offering free retums to consumers does not just help retail-ers avoid the negative consequences of fee retums. Depend-ing on the attribution condition, if customers received free retums, postretum spending at that retailer was 158%- 457% of preretum spending by the end of two years (see Figures 4 and 5). This is one of a few articles suggesting that product retums and their associated frustrations and costs for retailers are not "necessary evils" (to use Petersen and Kumar's [2009] term). Wood (2001) suggests the value to retailers of lenient retum policies, supporting the expec-tation that after customers have taken possession of the product they are also more likely to keep it. Anderson, Hansen, and Simester (2009) assess the value to consumers (and ultimately to retailers) of offering the retum option. Furthermore, up to a given threshold, more retums result in an increase in repurchases (Petersen and Kumar 2009). The present research supports the assertion that reducing con-sumer costs and decreasing the hurdles associated with retums can increase the repurchases to retailers and result in long-term benefits. Some online retailers selling products with relatively high return rates, such as shoes (e.g., Zappos.com), fashion (e.g., Nordstrom.com), and luggage (e.g., ebags.com), have already adopted free retum shipping policies (Spencer 2003). Indeed, the previous owner of Zappos.com indicated the importance of free retums to get people to take a chance on purchases (Rapbel 2004). In a related and developing issue, online retailers are increasingly willing to offer free (initial) shipping to customers to heighten the possibility of an initial purchase, recognizing that the increase in sales more than make up for the increase in costs (Zimmerman and Mattioli 2011). Our findings indicate that beyond avoiding the negative consequences of fee retums, there are the substantial advantages to retailers of free retums. While our studies were conducted in online settings, the implications of our findings may generalize to other retailer settings. These findings may also have implications for brick-and-mortar retailers, when the retum of the product entails a cost. Although restocking fees are often intended to get customers to "think twice" about retums (Meyer 1999), they may actually limit future customer spending for fear of future restocking fees. Finally, the products in Study 1 represented a wide cross-section of products from apparel to housewares to decorative items (representing more than 200 stockkeeping units), whereas the products in the second study were a wide variety of consumer electronics and accessories (representing more than 800 stockkeeping units). This diversity of the product categories represented across both studies suggests that the implications of these findings may generalize to retailers carrying a variety of product types. Further research should determine whether these findings generalize to retailers carrying a limited depth or breadth of product line, particularly with regard to the benefits of free retums. If a retailer has a limited variety or depth of product, especially if it is a product that need not be purchased frequently, rejoicing customers may only be able to purchase so much, regardless of their lack of anticipated regret. However, the advantages to the retailer of a free retum may accrue to the retailer in other ways, such as word of mouth (e.g., Oliver 1997). The Original and Important Role of Regret Consistent with the expectations of equity-based retum shipping policies, perceptions of fairness are positively related to postretum spending. However, the importance of faimess is not consistent with retailer expectations. We found that those perceptions of faimess are mediated by a reaction unanticipated by retailers: regret. Consumers regret purchasing from a company that has treated them unfairly, which leads to a decrease in postretum repurchases. Consis-tent with the ideas of Xia, Monroe, and Cox (2004), this may be due to the consumer desire either to prevent future inequities or possibly to balance the past inequity by not repurchasing. Beyond its mediating relationship with fairness is regret's direct relationship with product return shipping policies. Hess, Chu, and Gerstner (1996) normatively assume that a rational consumer will judge nonrefundable charges such as retum shipping costs to be sunk costs, which should not play a role in subsequent decision mak-ing. However, consistent with previous research (e.g., Simonson 1992), a past fee return serves to increase con-cems regarding future fees stemming from a future pur- Return Shipping Policies of Online Retailers /121

- 13. chase and failed product, and this anticipation serves as a salient issue to customers in deciding whether they will pur-chase again from a retailer (Petersen and Kumar 2009). The dampening effect that these fees have on regret and ulti-mately on postretum shipping are impressive. For example, 24.8% of fee respondents in Study 1 and 32.4% in Study 2 had dropped to zero revenue by the end of two years post-retum, compared with 12% and 15% in the free retum group. Retailers appear to be underestimating the long-term benefit of a free retum to the retailer itself. The sense of rejoicing resulting from a free retum resulted in significant postretum repurchases. Similar to the saying "What would you do if you know you couldn't fail?" our respondents appeared to have the philosophy "What would you buy if you knew you wouldn't have to pay to retum it?" Sales increases were impressive in both studies by the end of two years postretum (Study 1: $620.80; Study 2: $2,552.68). Our partial support for Hi may be a further indication of the significance that regret plays in consumer reactions. Equity theory (and our hypothesis) would predict that a fee condition under strong retailer attribution conditions would result in disproportionately lower postretum repurchase. Although the interaction was significant, it was due to a dis-proportionate increase in postretum spending resulting from free retums received when consumers had weaker retailer blame. Interpreted in light of regret theory, these consumers may have rejoiced when they got a free retum from a blameless retailer. Aside from the practical managerial contributions of the present research, there is also a significant theoretical con-tribution. Both regret and equity are frequently discussed as antecedents of satisfaction and future behavior (e.g., Cooke, Meyvis, and Schwartz 2001; Lapidus and Pinkerton 1995; Oliver 1997). However, there is limited research that includes both constructs in the same discussion or analysis, and the relationship between regret and equity is infre-quently addressed. Chatterjee (2007) puts forth unsupported expectations suggesting that regret might serve as an under-lying mechanism in the relationship between next-purchase coupons and perceptions of retailer faimess. In their devel-opment of untested research propositions regarding con-sumer reactions to unfair prices, Xia, Monroe, and Cox (2004) argue that negative emotions, regret included, serve as the primary driver of future action. To the best of our knowledge, the present research represents the first tested hypotheses of the relationships between faimess, regret, and postpurchase behavior and, in particular, the first demon-stration that regret mediates the effects of faimess on post-purchase customer behavior. This finding suggests that cus-tomers do not simply have negative affect as a result of being treated unfairly but actually regret being treated unfairly and are motivated to avoid inequitable treatment in the future. Appendix Measures^ Experienced Regret (aT2 = -95, 073 = .96) 1.1 regret purchasing this product from (retailer name). 2.1 am feeling rejoiceful about buying this product from (retailer name), (reverse-coded) 3.1 should not have purchased this product from (retailer name). Cost Fairness (a = .96) 1. With respect to the retum shipping policy outcome, (retailer name) handled the retum in a fair manner. 2.1 believe (retailer name) applies retum shipping policies fairly when handling retums. 3. The final retum shipping policy outcome I received from (retailer name) was unfair, (reverse-coded) Pre- and Postreturn Customer Spending l.Year 2 prereturn customer spending (TO): U.S. dollar amount of annual purchases with (retailer name) from the 24 months preretum to 12 months preretum. 2. Year 1 prereturn customer spending (Tl): U.S. dollar amount of annual purchases with (retailer name) from the 12 months preretum to the product retum event. 3. Year 1 postreturn customer spending (T4): U.S. dollar amount of annual purchases with (retailer name) from the retum event to 12 months postretum. 4. Year 2 postreturn customer spending (T5): U.S. dollar amount of annual purchases with (retailer name) from 12 months postretum to 24 months postretum. Retaiier Attributions (a = .99) 1. (Retailer name) is responsible for my need to retum this product. 2. To what extent was (retailer name) responsible for the return that you experienced? (1 = "not at all responsible," and 7 = "totally responsible") 3. To what extent do you blame (retailer name) for this retum? (1 = "not at all," and 7 = "completely") Seif-Attributions (a = .99) 1.1 am responsible for my need to retum this product. 2. The retum that I experienced was my fault. 3. To what extent do you blame yourself for this retum? (1 = "not at all," and 7 = "completely") 'Unless noted, items were anchored by 1 = "strongly disagree" and 7 = "strongly agree." Confirmatory factor measurement mod-els across both studies indicate strong intemal consistency. The average variance extracted between each pair of constructs is greater than (j)2 (i.e., the squared correlation between two con-structs [Fomell and Larcker 1981]), indicating strong discriminant validity. Measurement model (Anderson and Gerbing 1988): Study 1: X^ = 830.19, d.f. = 294, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, and RMSEA = .07; Study 2: x^ = 3375.64, d.f. = 294, CFI = .95, TLI = .92, and RMSEA = .08. a = average composite alpha reliability estimate across both studies. 122 / Journal of Marketing, September 2012

- 14. Involvement (a = .85) 1. The purchase of this product was (1 = "very unimportant," and 7 = "very important"). 2. With regard to the purchase of this product, how concerned were you about the outcome? (1 = "very unconcerned," and 7 = "very concerned") 3. The purchase of this product (1 = "required very little thought," and 7 = "required a lot of thought"). Return Shipping Poiicy Awareness 1. Were you aware of (retailer name)'s retum shipping policy before completing your order? (1 = "no," and 2 = "yes") REFERENCES Anderson, Eric T., Karsten Hansen, and Duncan Simester (2009), "The Option Value of Retums: Theory and Empirical Evi-dence," Marketing Science, 28 (3), 405-423. Anderson, James C. and David W. Gerhing (1988), "Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach," Psychological Bulletin, 103 (3), 411-23. Baron, Reuben M. and David A. Kenny (1986), "Moderator- Mediator Variables Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considera-tions," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51 (6), 1173-82. Bassili, John N. and John P. Racine (1990), "On the Process Rela-tionship Between Person and Situation Judgments in Attribu-tion," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59 (5), 881-90. Berger, Joseph, Thomas L. Conner, and M. Hamit Fisek (1974), Expectation States Theory: A Theoretical Research Program. Cambridge, MA: Winthrop Publishers. Chatterjee, Patrali (2007), "Advertising Versus Unexpected Next Purchase Coupons: Consumer Satisfaction, Perceptions of Value, and Faimess," Journal of Product & Brand Manage-ment, 16(1), 59-69. Cooke, Alan D.J., Tom Meyvis, and Alan Schwartz (2001), "Avoiding Future Regret in Purchase-Timing Decisions," Jour-nal of Consumer Research, 27 (March), 447-59. Davis, Scott, Michael Hagerty, and Eitan Gerstner (1998), "Return Policies and the Optimal Level of 'Hassle,'" Journal of Eco-nomics and Business, 50 (5), 445-60. Fitzsimmons, Gavan J. (2008), "Death to Dichotomizing," Journal of Consumer Research, 35 (1), 5-8. Folkes, Valerie S. (1984), "Consumer Reactions to Product Fail-ure: An Attributional Approach," Journal of Consumer Research, 10 (March), 398^09. Fomell, Claes and David F. Larcker (1981), "Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measure-ment Effors," Journal of Marketing Research, 18 (February), 39-50. Gilly, Mary C. and Betsy D. Gelb (1982), "Post-Purchase Con-sumer Processes and the Complaining Consumer," Journal of Consumer Research, 9 (December), 323-28. Greenleaf, Eric A. (2004), "Reserves, Regret, and Rejoicing in Open English Auctions," Journal of Consumer Research, 31 (September), 264-73. Hess, James D., Wujin Chu, and Eitan Gerstner, (1996), "Control-ling Product Retums in Direct Marketing," Marketing Letters, 7 (4), 307-317. Homans, George Caspar (1961), Social Behavior: Its Elementary Forms. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World. Inman, J. Jeffrey, James S. Dyer, and Jianmin Jia (1997), "A Gen-eralized Utility Model of Disappointment and Regret Effects on Post-Choice Valuation," Marketing Science, 16 (2), 97-111. and Leigh McAlister (1994), "Do Coupon Expiration Dates Affect Consumer Behavior?" Journal of Marketing Research, 31 (August), 423-28. Irwin, Julie R. and Gary H. McClelland (2001), "Misleading Heuristics and Moderated Multiple Regression Models," Jour-nal of Marketing Research, 38 (February), 100-109. Johnson, Lee M., Rehan Mullick, and Charles L. Mulford (2002), "General Versus Specific Victim Blaming," Journal of Social Psychology, 142 (2), 249-63. Kandra, Anne (2000), "Shipping Charges: Who Foots the Bill?" PC World, 18 (9), 39. Kelley, Scott W., K. Douglas Hoffman, and Mark A. Davis (1993), "A Typology of Retail Failures and Recoveries," Journal of Retailing, 69 (4), 429-52. Krull, Douglas S. (2001), "On Partitioning the Fundamental Attri-bution Error: Dispositionalism and Correspondence Bias," in Cognitive Social Psychology: The Princeton Symposium on the Legacy and Future of Social Psychology, Gordon B. Moskowitz, ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 211-27. Landman, Janet (1987), "Regret and Elation Following Action and Inaction," Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 13 (December), 524-36. Lapidus, Richard S. and Lori Pinkerton (1995), "Customer Com-plaint Situations: An Equity Theory Perspective," Psychology & Marketing, 12 (2), 105-122. Lemon, Katherine N., Tiffany Bamett White, and Russell S. Winer (2002), "Dynamic Customer Relationship Management: Incor-porating Future Consideration into the Service Retention Deci-sion," Journal of Marketing, 66 (January), 11-14. Maxham, James G., Ill, and Richard G. Netemeyer (2003), "Firms Reap What They Sow: The Effects of Shared Values and Per-ceived Organizational Justice on Customer Evaluations of Complaint Handling," Journal of Marketing, 67 (January), 46-62. Meyer, Harvey (1999), "Many Happy Retums," Journal of Busi-ness Strategy, 20 (4), 27-31. Miller, Frederick D., Eliot R. Smith, and James Uleman (1981), "Measurement and Interpretation of Situational and Disposi-tional Attributes," Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 17(1), 80-95. Mollenkopf, Diana A., Elliot Rabinovich, Timothy M. Laseter, and Kenneth K. Boyer (2007), "Managing Internet Product Retums: A Focus on Effective Service Operations," Decision Sciences, 38 (2), 215-50. Neff, James A. (1985), "Race and Vulnerability to Stress: An Examination of Differential Vulnerability," Journal of Person-ality and Social Psychology, 49 (2), 481-91. Nisbett, Richard E. and Lee Ross (1980), Human Inference: Strategies and Shortcomings of Social Judgment. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Oliver, Richard L. (1997), Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer. Boston: Richard D. Irwin/McGraw-Hill. and John E. Swan (1989a), "Consumer Perceptions of Interpersonal Equity and Satisfaction in Transactions: A Field Survey Approach," Journal of Marketing, 53 (April), 21-35. Return Shipping Policies of Online Retailers /123

- 15. and (1989b), "Equity and Disconfirmation Percep-tions as Influences on Merchant and Product Satisfaction," Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (December), 372-83. O'Shaughnessy, John and Nicholas Jackson O'Shaughnessy (2005), "Considerations of Equity in Marketing and Nozick's Decision-Value Model," Academy of Marketing Science Review, 10, (published electronically), [available at http:// www.amsreview.org/articles/oshaughnessy 10-2005 .pdf]. Padmanabhan, V. and I.P.L. Png (1997), "Manufacturer's Retums Policies and Retail Competition," Marketing Science, 16 (1), 81-94. Pastemack, Barry Alan (2008), "Optimal Pricing and Return Poli-cies for Perishable Commodities," Marketing Science, 27 (1), 133^0. Petersen, J. Andrew and V. Kumar (2009), "Are Product Retums a Necessary Evil? Antecedents and Consequences," Journal of Marketing, 73 (May), 35-51. Raphel, Murray (2004), "And Many Happy Retums," Art Business News,31 (1),46. Ratchford, Brian (1987), "New Insights About the FCB Grid," Journal of Advertising Research, 27 (4), 24-39. Simonson, Itamar (1992), "The Influence of Anticipating Regret and Responsibility on Purchase Decisions," Journal of Con-sumer Behavior, 19 (June), 105-118. Smith, Amy K., Ruth N. Bolton, and Janet Wagner (1999), "A Model of Customer Satisfaction with Service Encounters Involving Failure and Recovery," Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (August), 356-73. Solomon, Sheldon (1978), "Measuring Dispositional and Situa-tional Attributions," Personality and Social Psychology Bul-letin, 4 (4), 5S9-94. Spencer, Jane (2003), "'I Ordered ThatT Web Retailers Make It Easier to Retum Goods," The Wall Street Journal, (September 4),D1-D2. Swan, John E. and Richard L. Oliver (1991), "An Applied Analy-sis of Buyer Equity Perceptions and Satisfaction with Automo-bile Salespeople," Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Man-agement, 11 (2), 15-26. Tax, Stephen S., Stephen W. Brown, and Murali Chandrashekaran (1998), "Customer Evaluations of Service Complaint Experi-ences: Implications for Relationship Marketing," Journal of Marketing, 62 (April), 60-76. Taylor, Shelley E. and Judith H. Koivumaki (1976), "The Percep-tion of Self and Others: Acquaintanceship, Affect, and Actor- Observer Differences," Journal of Personality and Social Psy-chology, 33 (4), 403^08. Tsiros, Michael and Vikas Mittal (2000), "Regret: A Model of Its Antecedents and Consequences in Consumer Decision Mak-ing," Journal of Consumer Research, 26 (March), 401^17. Valle, Valerie and Melanie Wallendorf (1977), "Consumers' Attri-butions of the Cause of Their Product Satisfaction and Dissat-isfaction," in Consumer Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Com-plaining Behavior, Ralph L. Day, ed. Bloomington: Indiana University, 26-30. Verhoef, Peter C, Philip Hans Eranses, and Janny C. Hoekstra (2001), "The Impaet of Satisfaction and Payment Equity on Cross-Buying: A Dynamic Model for a Multi-Service Provider," Journal of Retailing, 11 (3), 359-78. Vorhees, Clay M., Michael K. Brady, and David M. Horowitz (2006), "A Voice from the Silent Masses: An Exploratory and Comparative Analysis of Noncomplainers," Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34 (4), 514-27. Walster, Elaine, Ellen Berscheid, and G. William Walster (1973), "New Directions in Equity Research," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,25 (February), 151-76. Weiner, Bernard (2000), "Attributional Thoughts About Consumer Behavior," Journal of Consumer Research, 27 (December), 382-87. White, Peter (1991), "Ambiguity in the Internal/External Distinc-tion in Causal Attribution," Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 27 (3), 259-70. Wolf, Alan (2012), "CE Retums Cost Industry $17B in 2011: Report," Twice, 27 (1), 82. Wood, Staey L. (2001), "Remote Purehase Environments: The Influence of Retum Policy Leniency on Two-Stage Decision Processes," Journal of Marketing Research, 38 (May), 157-69. Xia, Lan, Kent B. Monroe, and Jennifer L. Cox (2004), "The Price Is Unfair! A Conceptual Eramework of Price Eaimess Percep-tions," Journal of Marketing, 68 (October), 1-15. Zeelenberg, Marcel, Wilco W. van Dijk, and Antony S.R. Manstead (1998), "Reconsidering the Relation Between Regret and Responsibility," Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 74 (3), 254-72. Zimmerman, Ann and Dana Mattioli (2011), "Ship Eree or Lose Out: More Retailers Absorb Cost of Sending Packages to Vie with Web-Only Rivals," The Wall Street Journal, (November 25),Bl. 124 / Journal of IVIarketing, September 2012

- 16. Copyright of Journal of Marketing is the property of American Marketing Association and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.