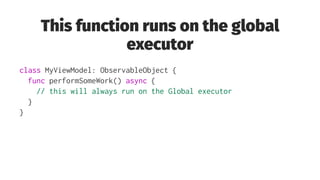

- Async functions run on the global executor by default, but can be instructed to run on the main actor using annotations like @MainActor. Using nonisolated allows escaping the main actor.

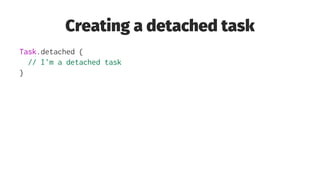

- Tasks are used to represent independent units of work but do not affect execution context. Unstructured tasks inherit context, detached tasks inherit nothing.

- Structured concurrency relates to the relationships between parent and child tasks. A parent task cannot complete until its children finish.

![Actors synchronize access to their

(mutable) state

actor DateFormatters {

private var formatters: [String: DateFormatter] = [:]

func formatter(using dateFormat: String) -> DateFormatter {

if let formatter = formatters[dateFormat] {

return formatter

}

let newFormatter = DateFormatter()

newFormatter.dateFormat = dateFormat

formatters[dateFormat] = newFormatter

return newFormatter

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/brainonconcurrency-230421123109-8bddc1dd/85/Your-on-Swift-Concurrency-64-320.jpg)