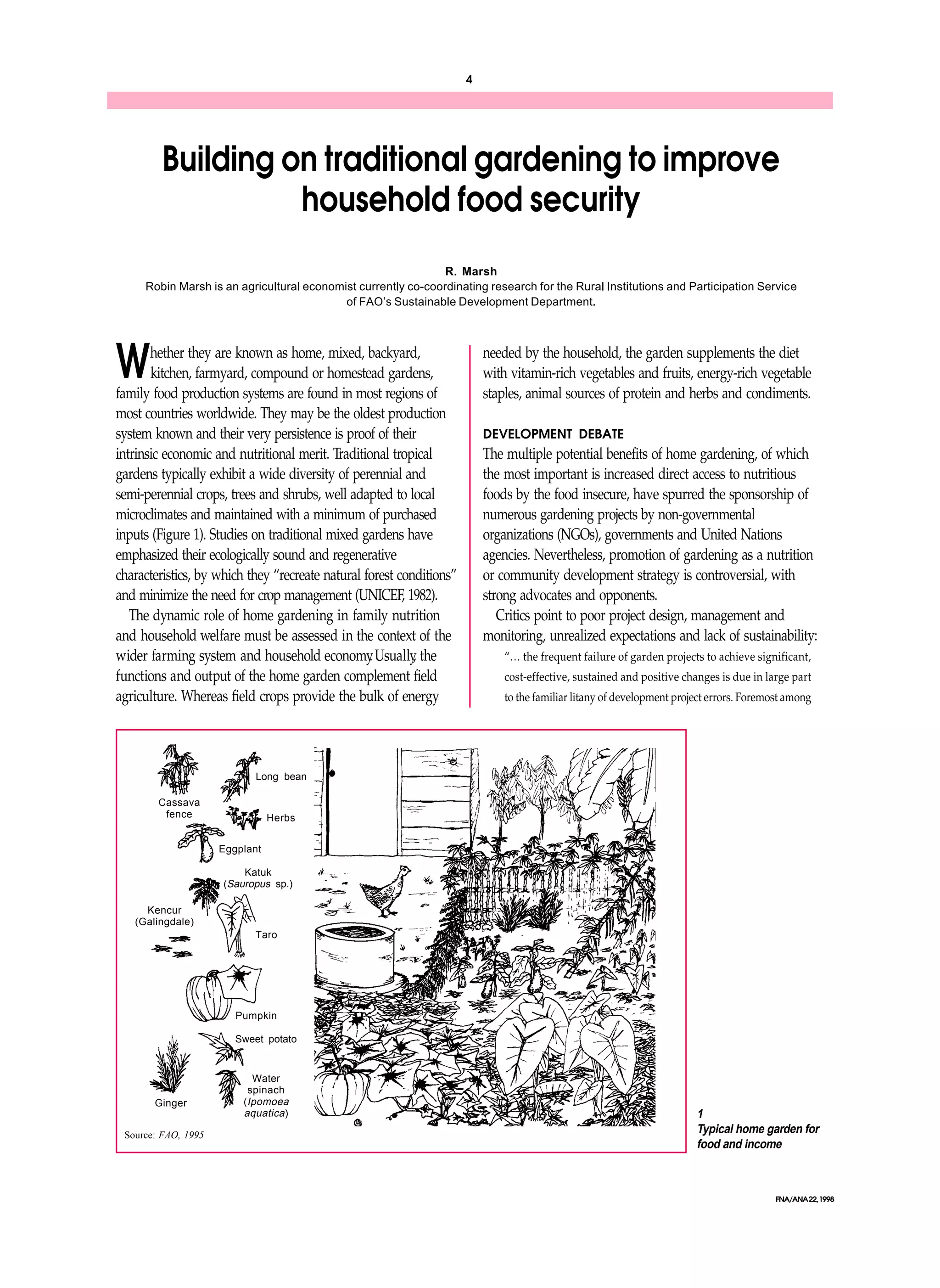

The document discusses the role of home gardening in improving household food security, emphasizing its benefits and the controversies surrounding its promotion as a sustainable strategy. Home gardens contribute to family nutrition and income but face criticism over project management and sustainability issues. Successful gardening initiatives depend on understanding local conditions and integrating traditional gardening practices, while also involving the community, especially women, in the planning and management processes.