This document discusses whether stock markets promote economic growth. It begins by outlining the debate on whether financial development causes growth or vice versa. The authors then:

1) Describe previous empirical studies on the relationship between financial development/stock markets and economic growth that have limitations in establishing causality.

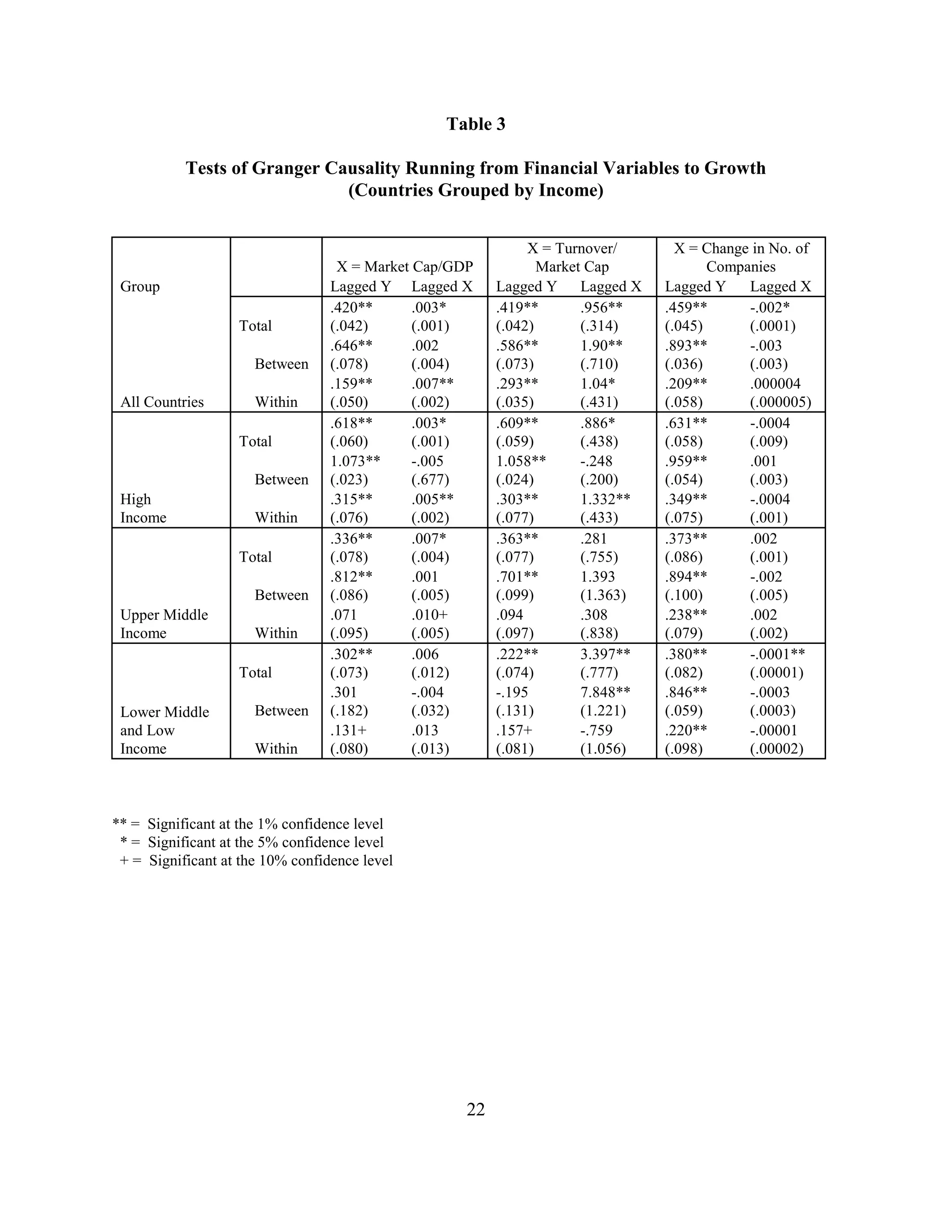

2) Explain their use of Granger causality tests on data from 64 countries over varying time periods to help determine the causal direction of the relationship.

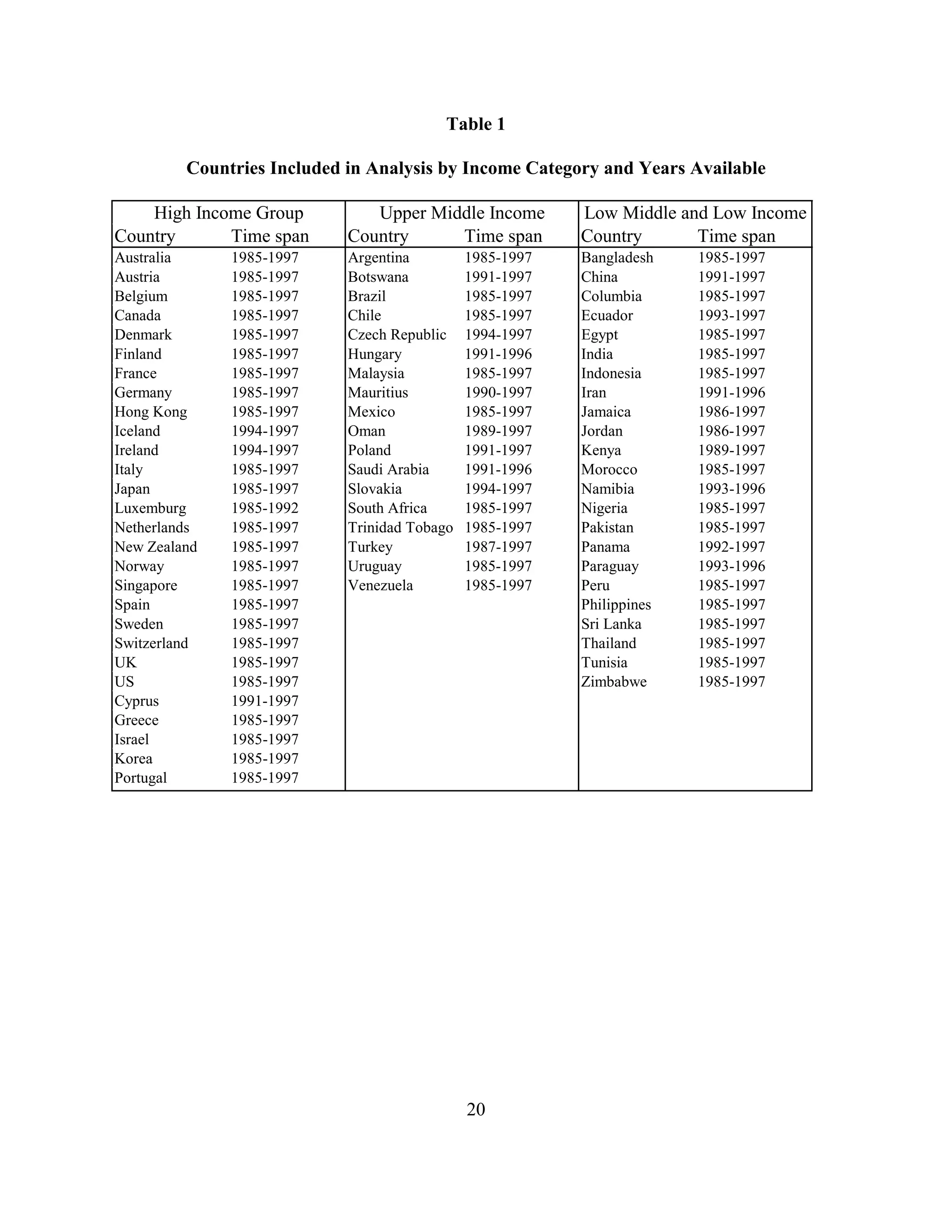

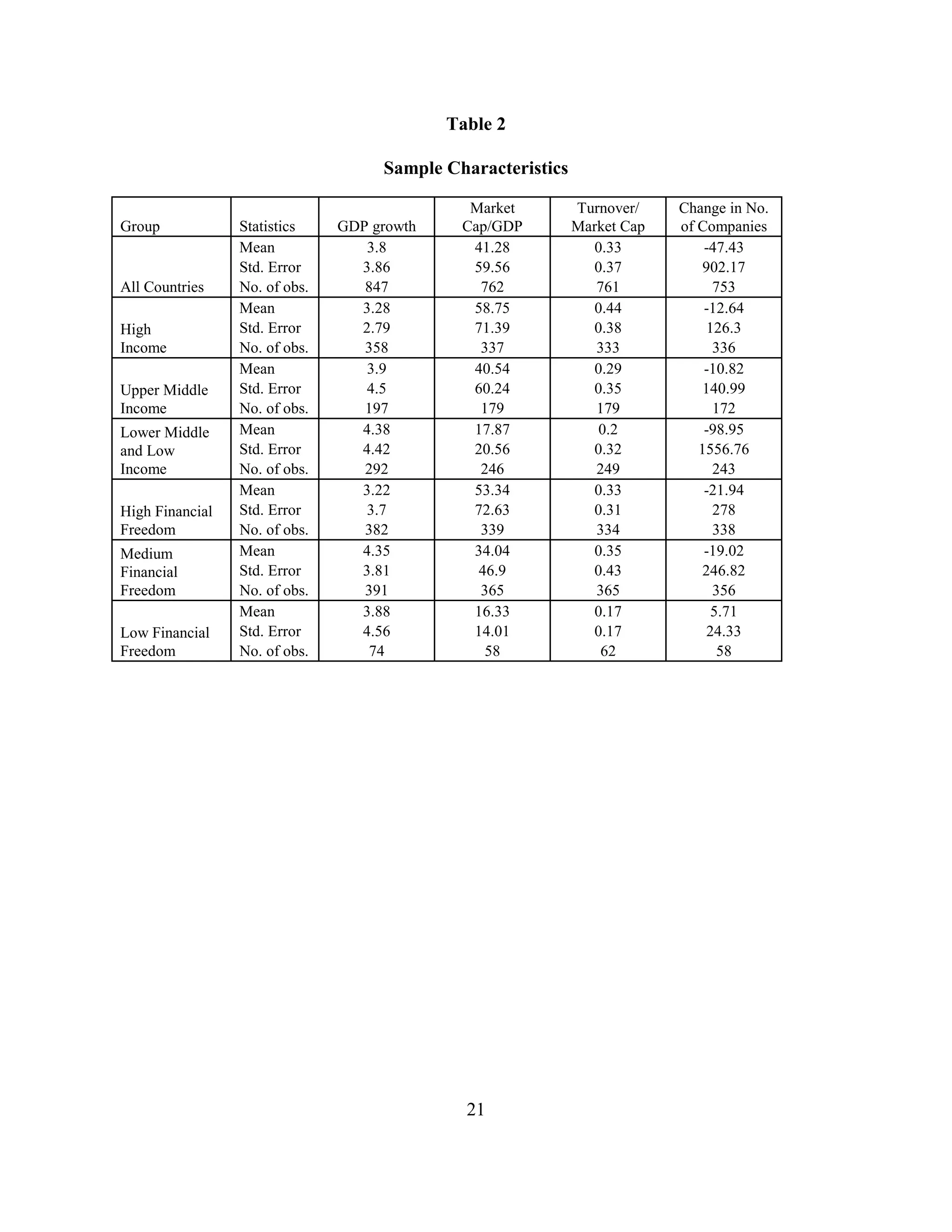

3) Present sample statistics showing differences in growth rates and financial development across income levels and degrees of financial market freedom.

![Given the complications and efficiency loss imposed by attempting to correct for bias in

estimates of the coefficients in Equations (1) and (2) arising from the dynamic panel nature of the

data, we rely on simulations results in Judson and Owen (1999) showing that bias problems are

almost entirely concentrated in the coefficient on the lagged dependent variables, while biases in the

coefficients of independent variables (beta and delta in Equations (1) and (2)) are “relatively small

and cannot be used to distinguish between estimators [including OLS] (p. 13).” Given that we are

not interested in point estimates of these coefficients, that any biases that exist apparently work

against our finding significant causality, and that correction for biases would result in a significant

loss of efficiency that would do more damage to a search for causal relationships than a relative

small coefficient bias, we have elected to ignore bias corrections in the results that follow.

4. Results

lagged levels over lagged differences.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wp267-110302225511-phpapp01/75/Wp267-10-2048.jpg)

![Schumpeter, J. 1912. Theorie der Wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung [The

Theory of Economic Development]. Leipzig: Dunker & Humblot

[Cambridge, M.A.: Harvard University Press, 1934. Translated by

Redvers Opie].

Schwarz, G. 1978. “Estimating the Dimension of a Model," Annals of

Statistics. 6: 461-464.

Spears, Annie. 1991. “Financial Development and Economic Growth -

Causality Tests,” Atlantic Economic Journal. 19: 66.

Thornton, John. 1995. “Financial Deepening and Economic Growth in

Developing Countries,” Economia Internazionale. 48(3): 423-30.

WIDER (World Institute for Development Economics Research). 1990

Foreign Portfolio Investment in Emerging Equity Markets. Helsinki:

WIDER.

World Bank. 1999. World Development Report 1998/99: Knowledge for

Development. Washington, D.C.: Oxford University Press.

19](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wp267-110302225511-phpapp01/75/Wp267-21-2048.jpg)