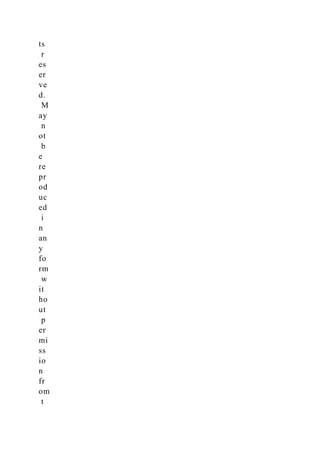

The document outlines a questionnaire for summarizing a proposed project, including the organization's identity, mission, project details, importance, expected accomplishments, credibility, and funding requirements. It also delves into the history of immigration to the United States, categorizing it into four distinct periods and highlighting the significant contributions of various immigrant groups to American society. The narrative emphasizes the integral role of immigrants in shaping America's diverse identity and acknowledges both historical and contemporary challenges related to immigration.

![Growing fear of immigrants

A

m

er

ic

an

Im

m

ig

ra

ti

o

n

36

garb and poverty of most newcomers. The prominent sociologist

Edward A. Ross spelled out these suspicions about racial

difference and inferiority when he noted in 1914 that “the

physiognomy of certain groups unmistakably proclaims

inferiority

of type.” In every face, he noted “something wrong. . . . There

were

so many sugar-loaf heads, moon faces, slit mouths, lantern jaws,

and goose-bill noses that one might imagine a malicious jinn

[genie] had amused himself by creating human beings in a set of

skew-molds discarded by the Creator.”

Another difference was the new immigrants’ greater](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/worksheet10-221011183901-569c85de/85/WORKSHEET-10-1A-Summary-QuestionnaireUse-the-filled-out-W-docx-131-320.jpg)

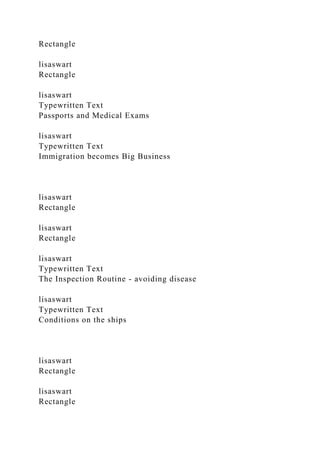

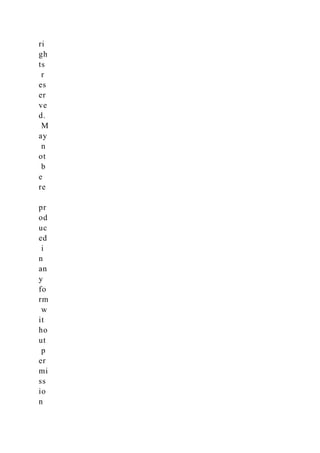

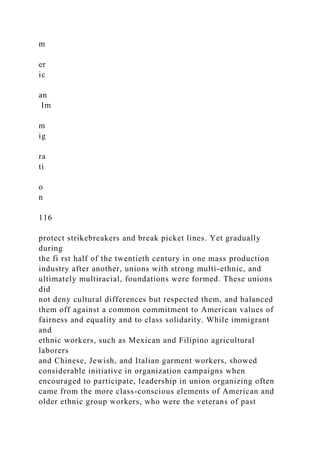

![PAPER 2: IMMIGRATION TO THE USA (1880S -

1930)

All in all, it is estimated that between 1880 and 1930, around

28-30 million immigrants entered the United States.

Background:

“The 1880s marked a turning pointin the history

of American immigration, as well as the

American attitude toward it. In the first place,

the annual rate rose dramatically. The number of

arrivals from Europe went up more than 100%

from 1879 to 1881, and it more than tripled

during the next year…The shift from northeast to

southwest [and Eastern] Europe as a source for

immigration, which began about 1883,

and increased rapidly until the first decades of

the 20th century (the 1900s), brought unfamiliar

cultures in unprecedented numbers to the United

States”

(Wepman,160)

Global Context: “It was a period of

unprecedented migration throughout the world.

People were moving from one nation in Europe

to another, from Europe to Australia and South

America, from Asia to both Europe and the

Americas. In the first 2 decades of the 20th

century, Canada received nearly 3 million

people, Argentina admitted more than 2 million,

and Brazil about 1 million. Australia and

New Zealand admitted some900,000 European

immigrants during this period. However, the

United States remained the most popular](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/worksheet10-221011183901-569c85de/85/WORKSHEET-10-1A-Summary-QuestionnaireUse-the-filled-out-W-docx-325-320.jpg)