1. The document discusses the history and evolution of optics from ancient times to the 11th century CE. It describes how early civilizations like the Greeks, Chinese, and Phoenicians made early observations and experiments with light, lenses, mirrors, and vision.

2. The work of the ancient Greek philosophers such as Euclid, Ptolemy, and Aristotle helped develop early theories of light, but it was not until the 11th century Arab scholar Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) that many modern theories of vision and optics began to take hold. Through experiments with lenses, mirrors, and the camera obscura, Alhazen helped debunk earlier theories and establish that light travels in straight lines

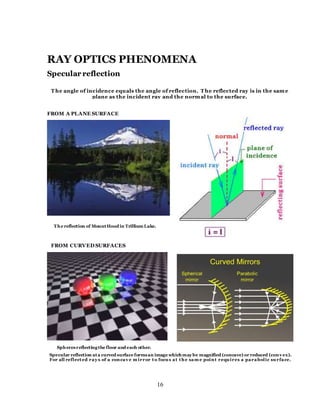

![20

Through a plane wedged glass plate

Through lenses

.

Lensmaker’s formula

1/f = (n-1) [1/R1 – 1/R2 + (n-1)d/nR1R2]

where

f is the focal length ofthe lens,

n is the refractiveindex ofthe lens

material,

R1 is the radius ofcurvatureofthe

lens surface closest to the light

source,

R2 is the radius of curvatureofthe

lens surface farthest from the light

source,and

d is the center thicknessofthe lens

(the distance along the lens axis

between the two surface vertices).

Light from an object that is at a distance

beyondthe lens focal length forms a real

image on the side of the lens opposite the

object. Magnification (reduction) ofthe

image is S2 / S1. For an objectat infinity (or

very far away from the lens) the image will be

a small focused spot.

Light from an object that is at a distance less

than the lens focal length forms a virtual

image on the same side of the lens as the

object. Magnification ofthe image is S2 / S1.

This is the principle ofa magnifying glass.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/112ccee8-35a6-4aa6-9738-adeb62df7591-150902162927-lva1-app6891/85/What-is-optic1-20-320.jpg)