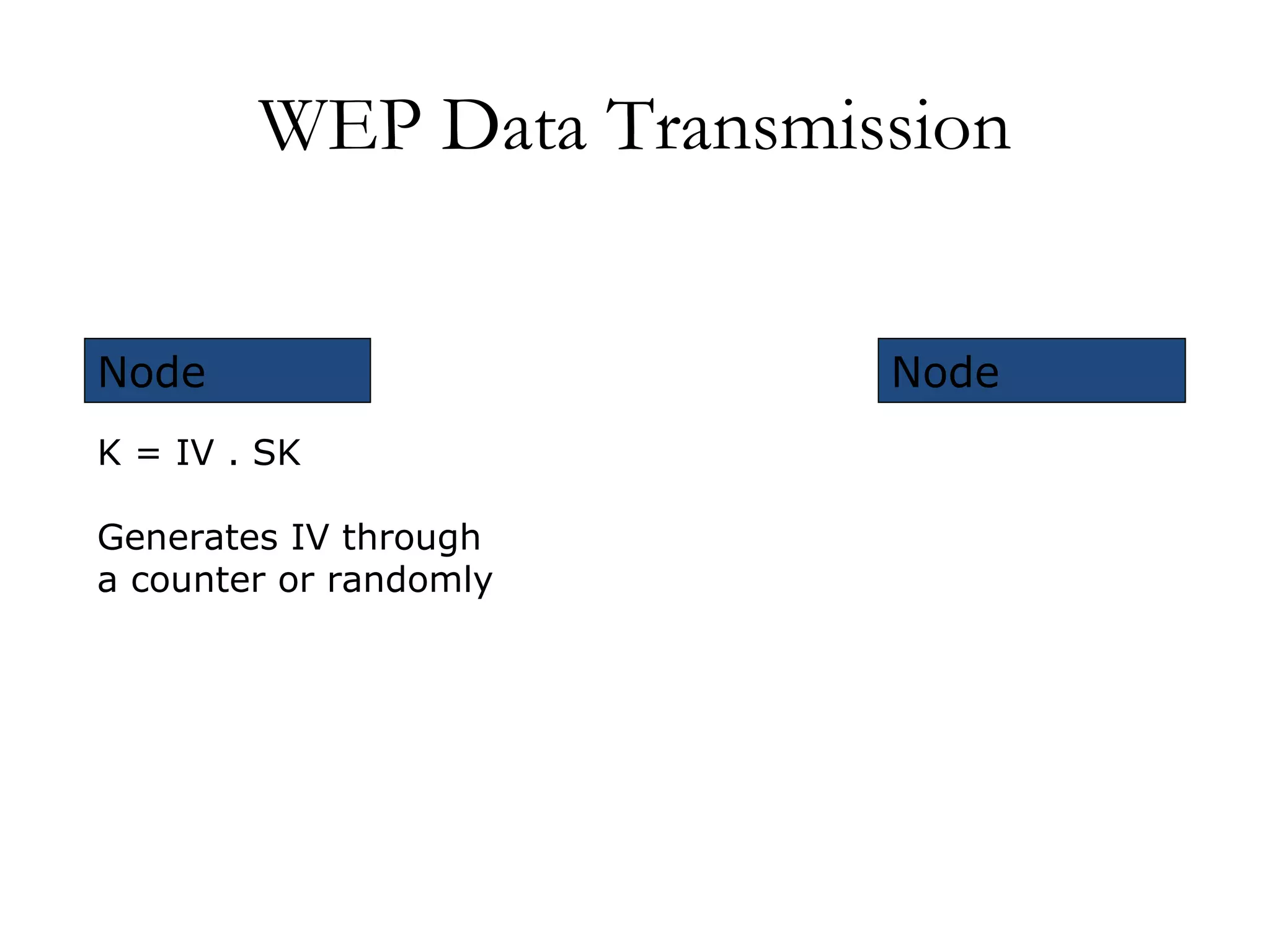

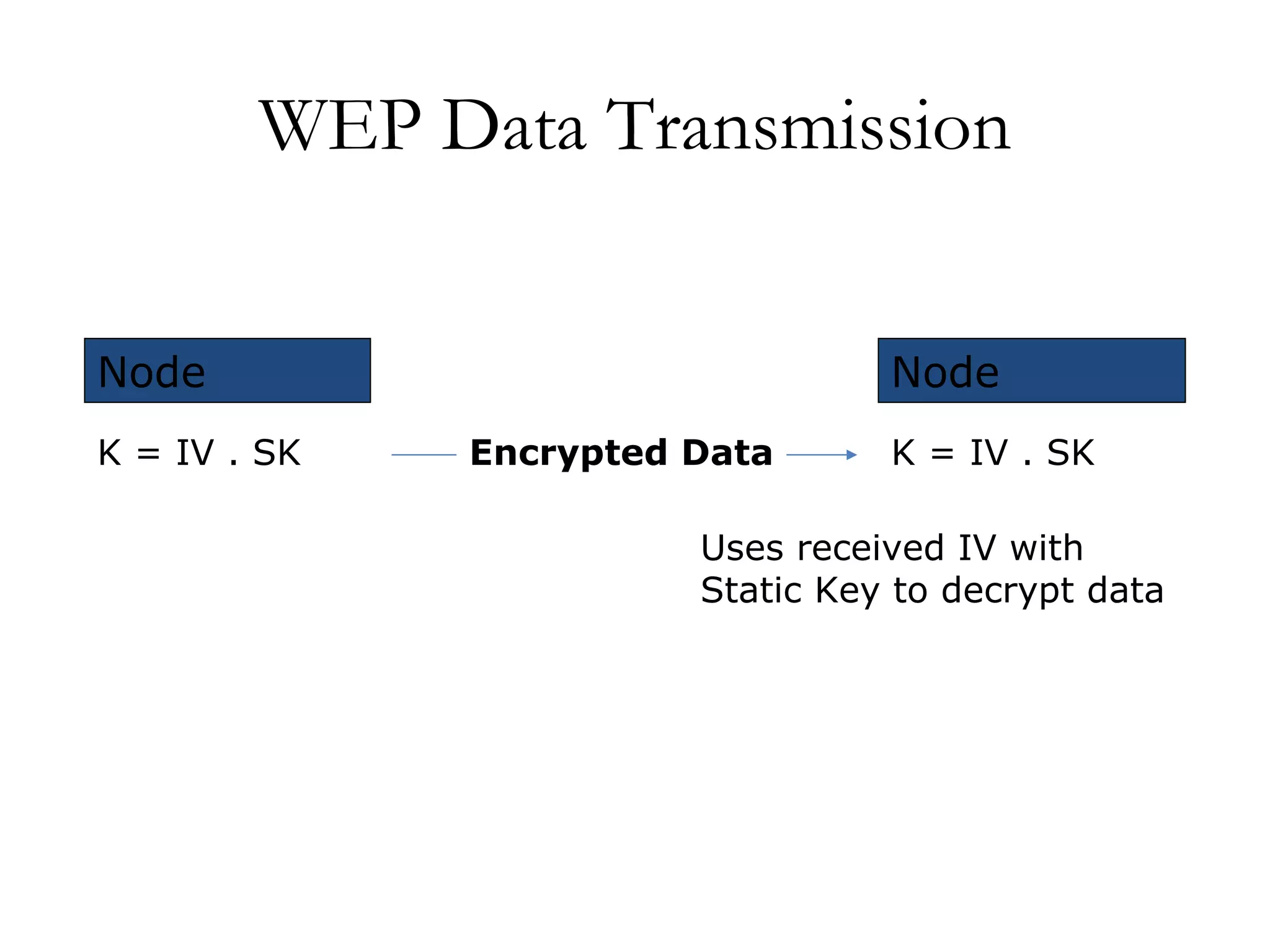

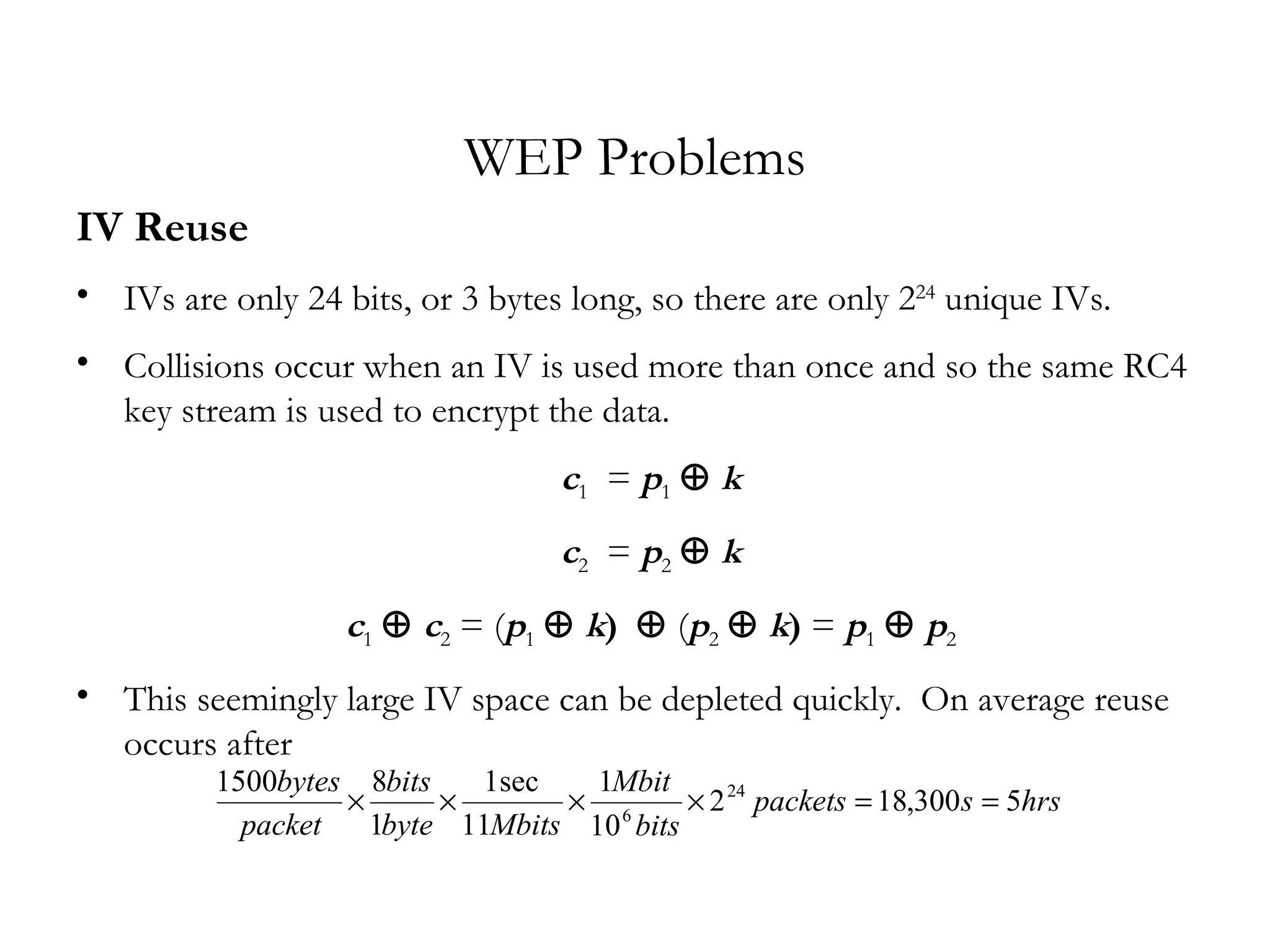

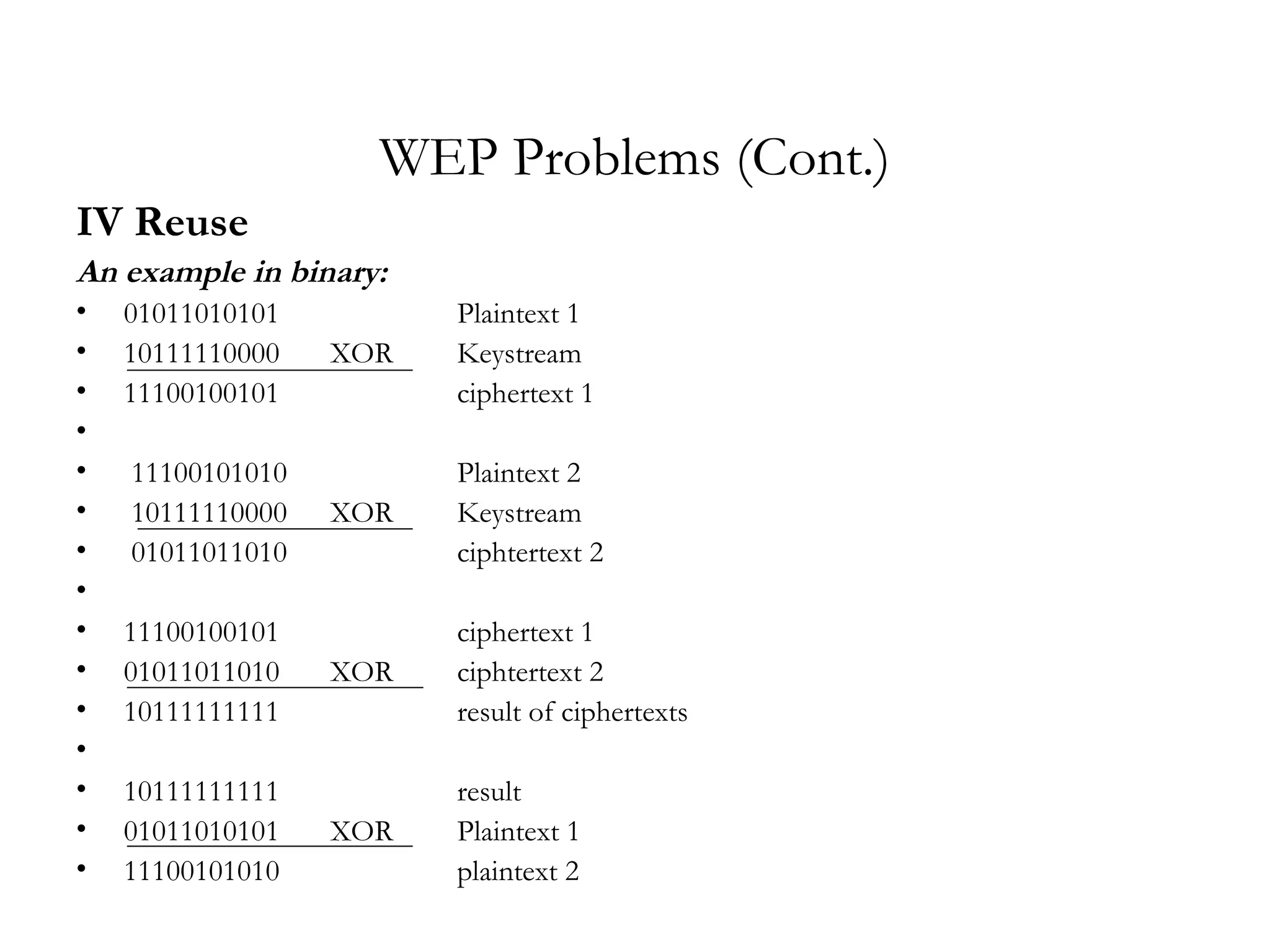

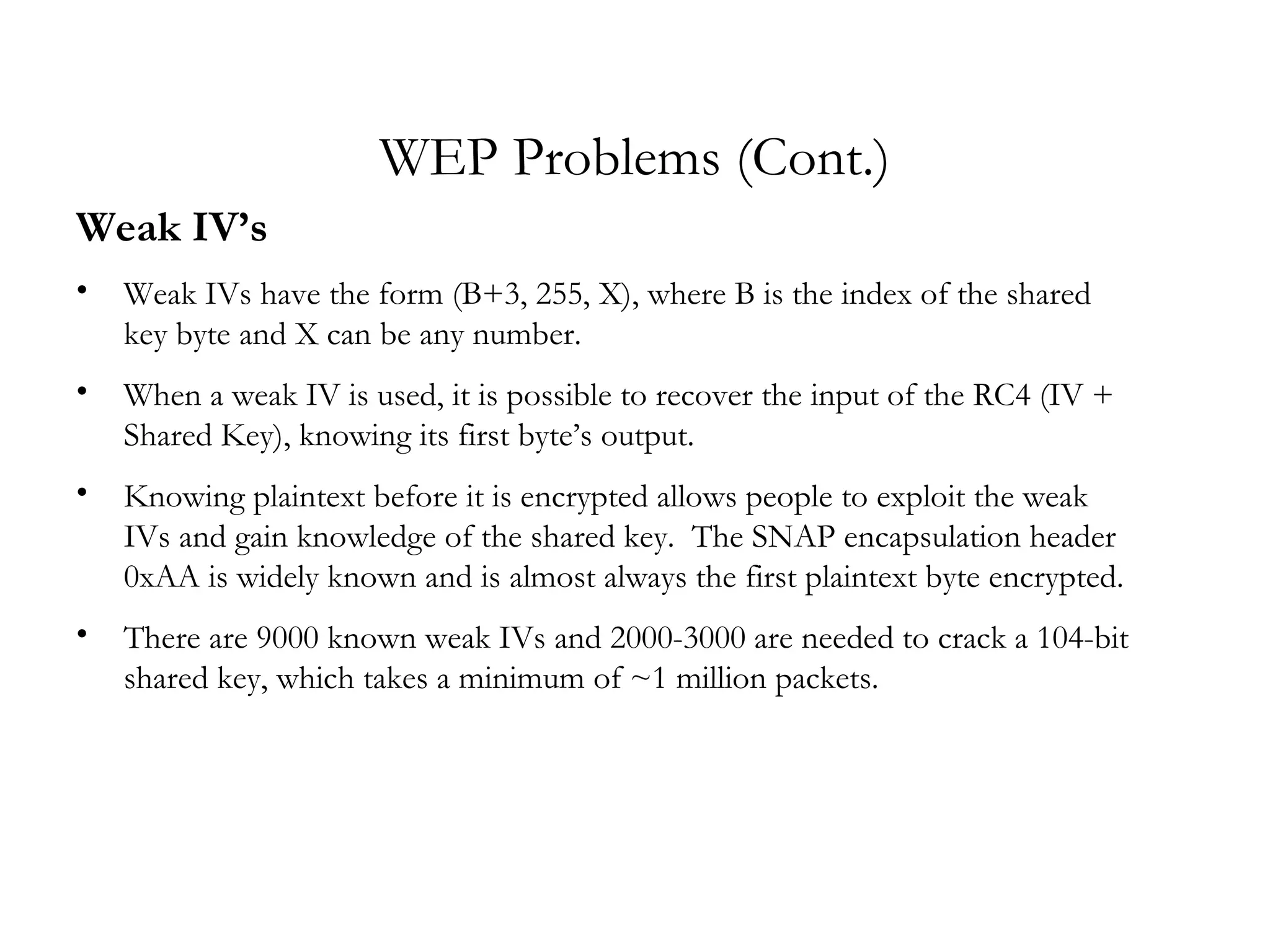

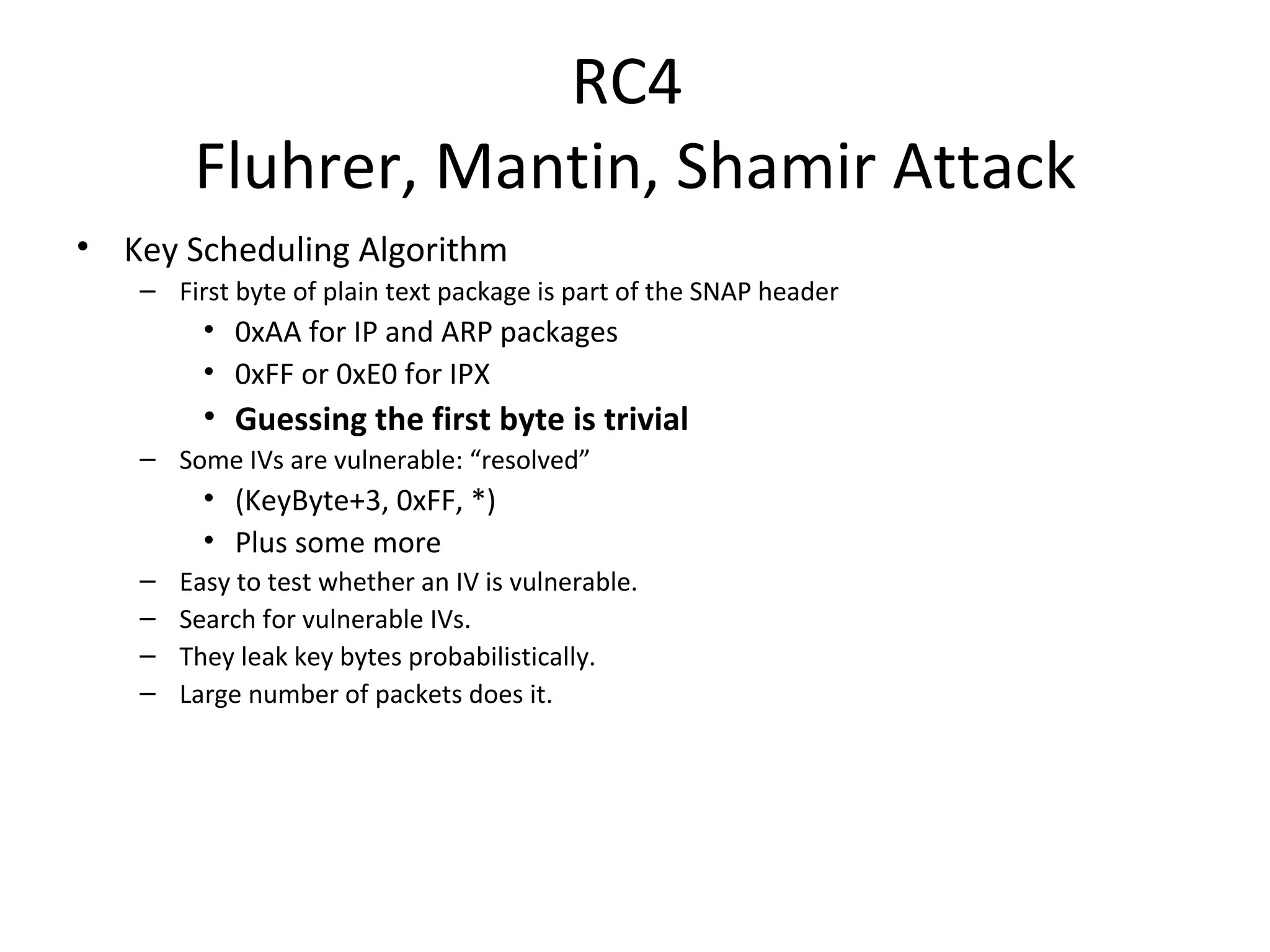

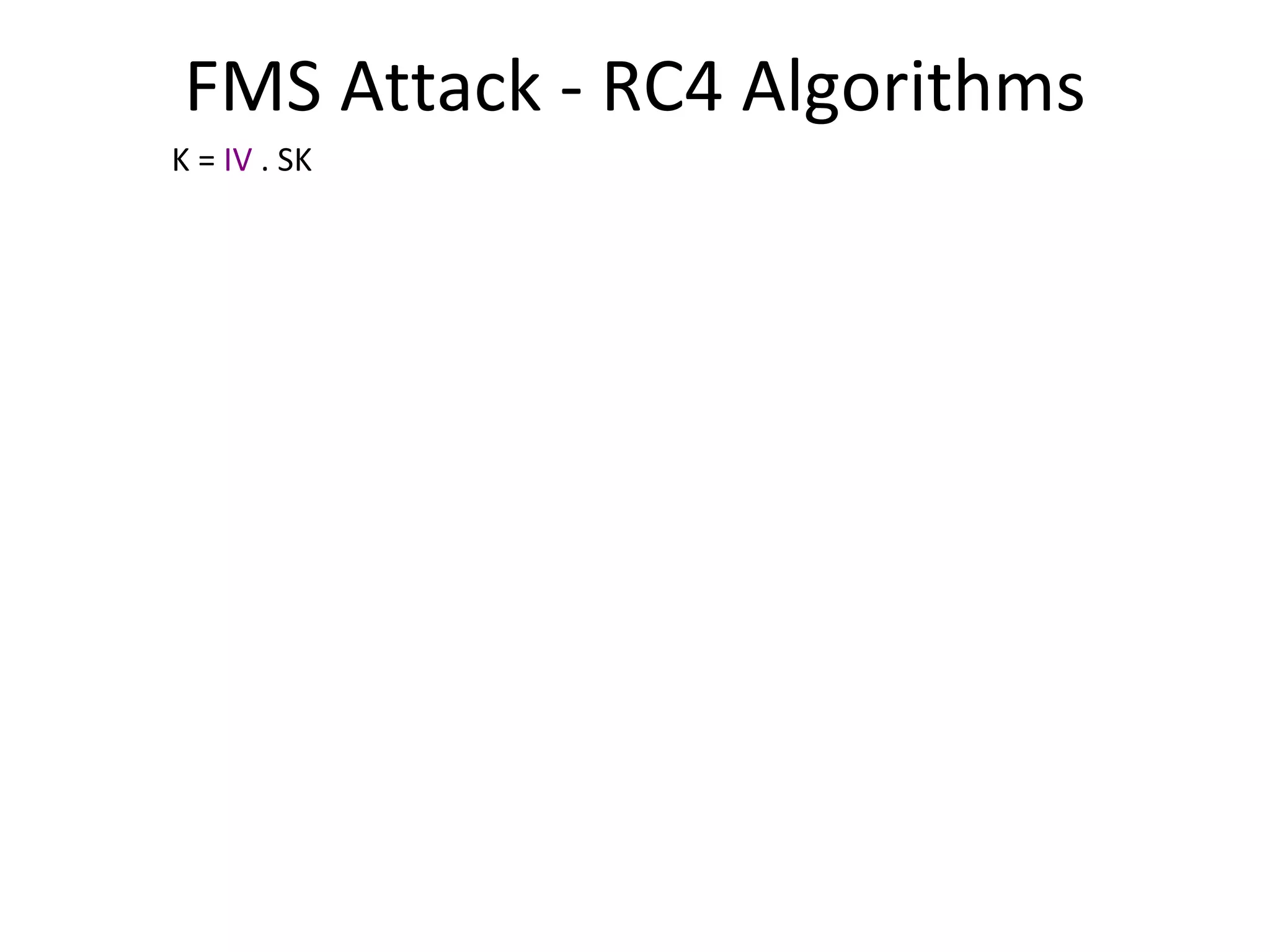

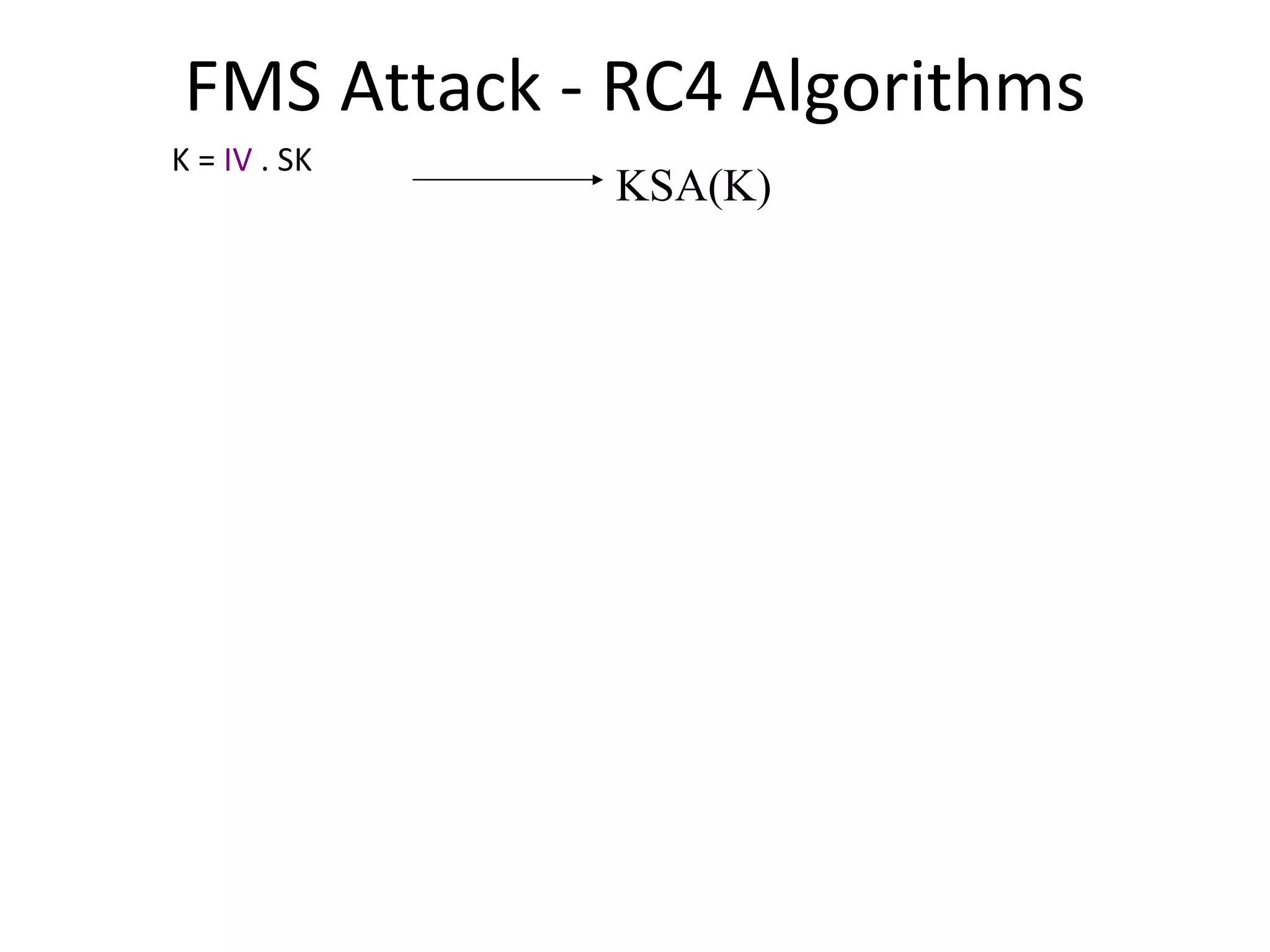

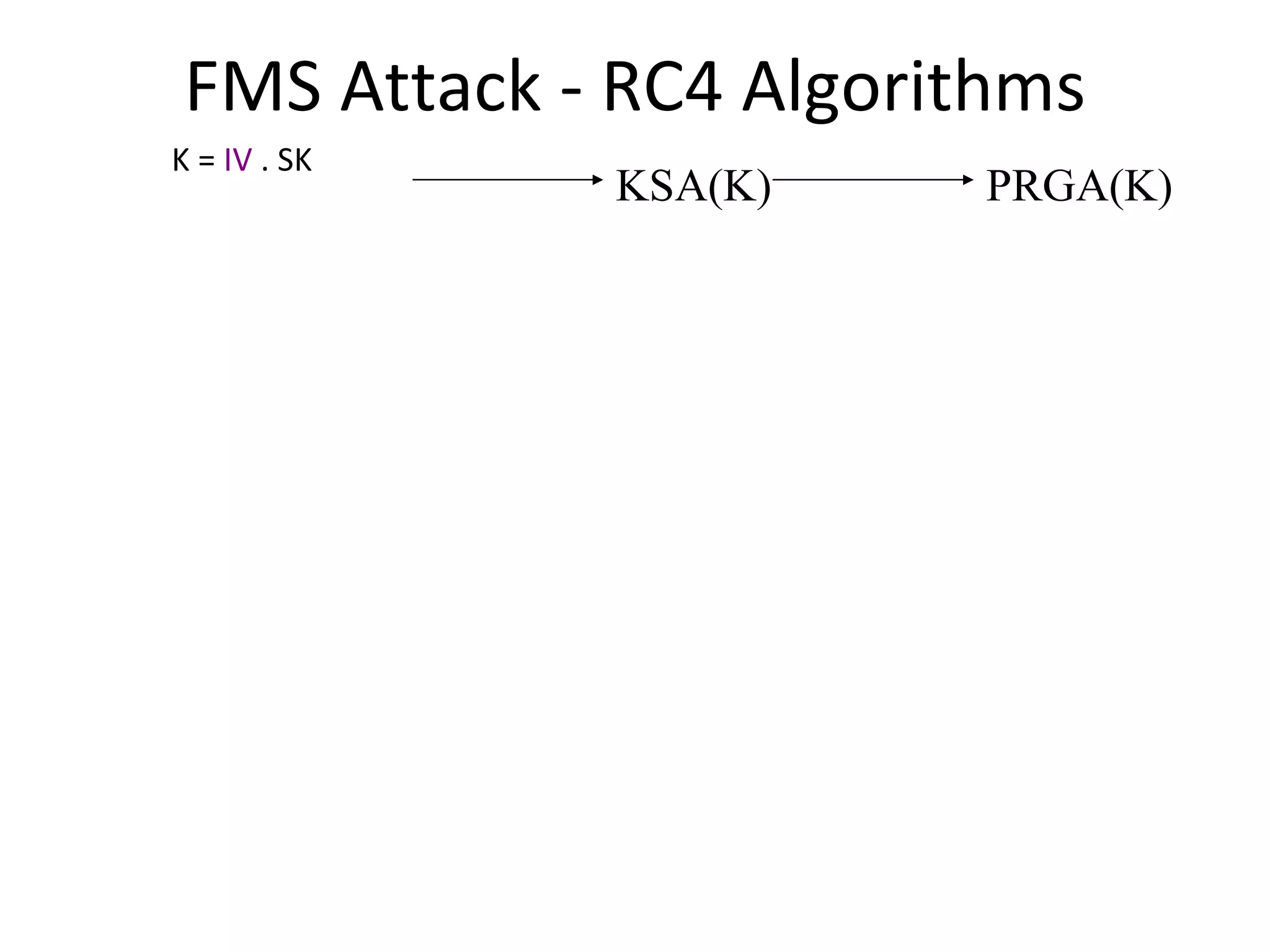

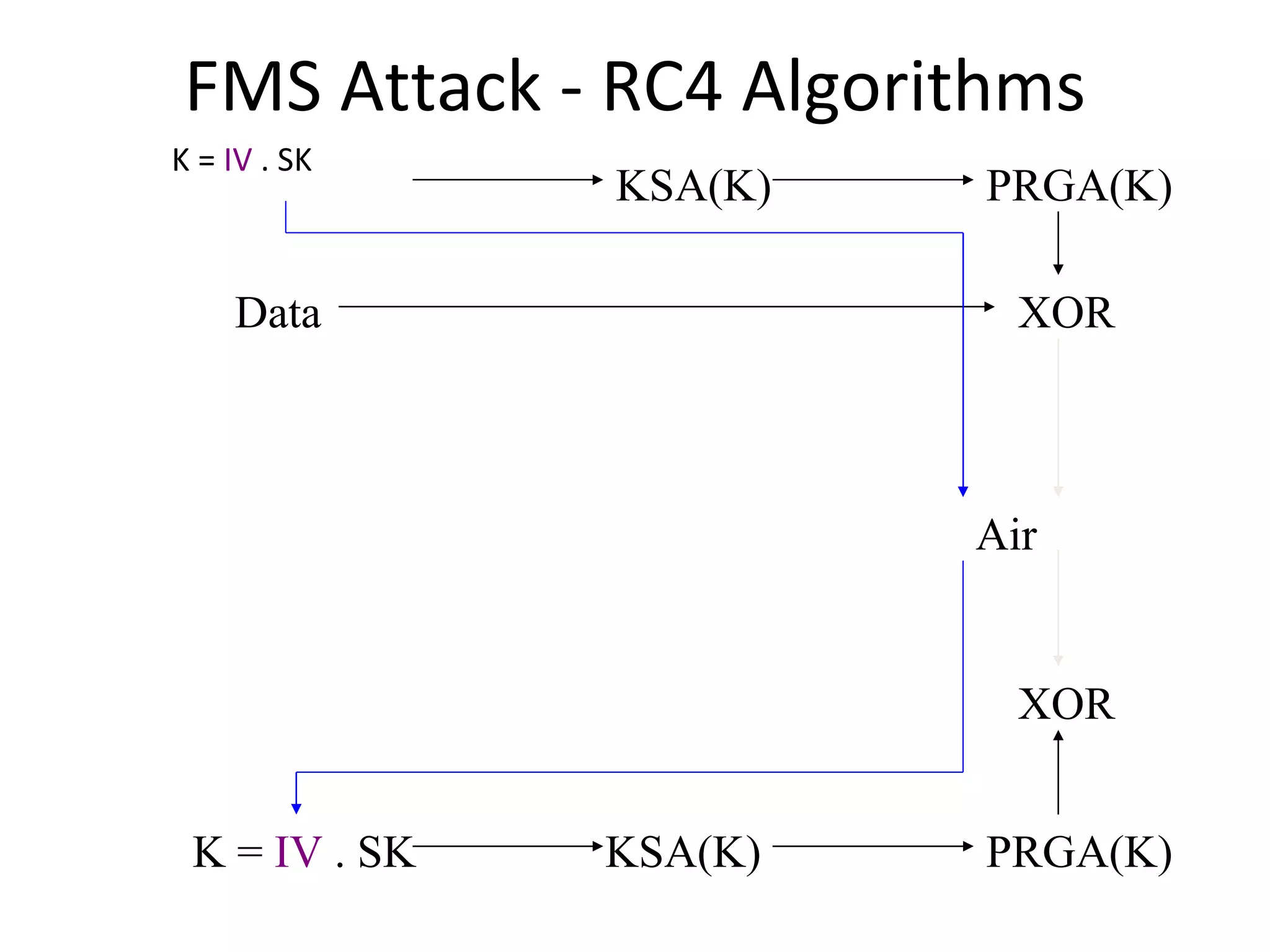

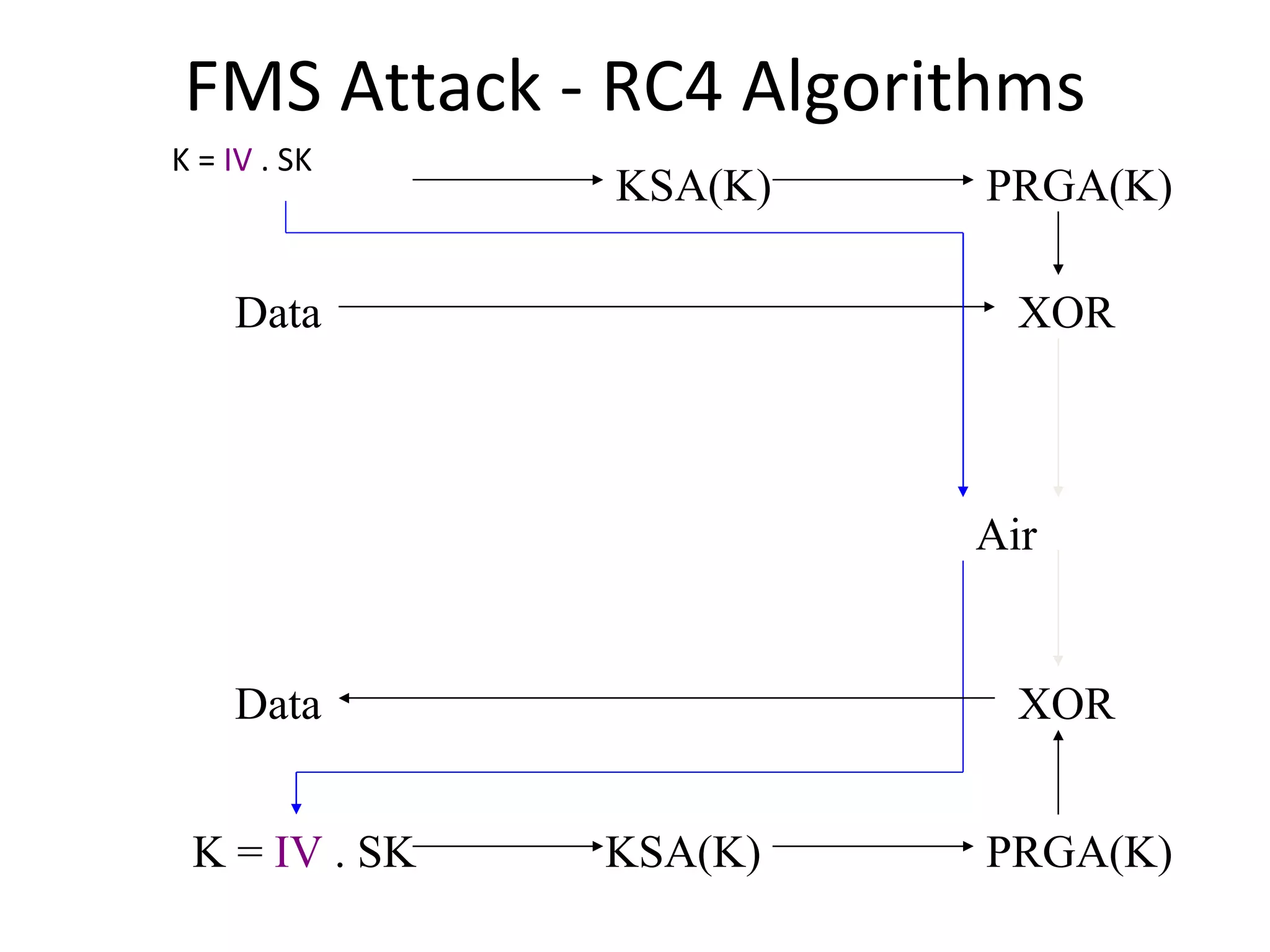

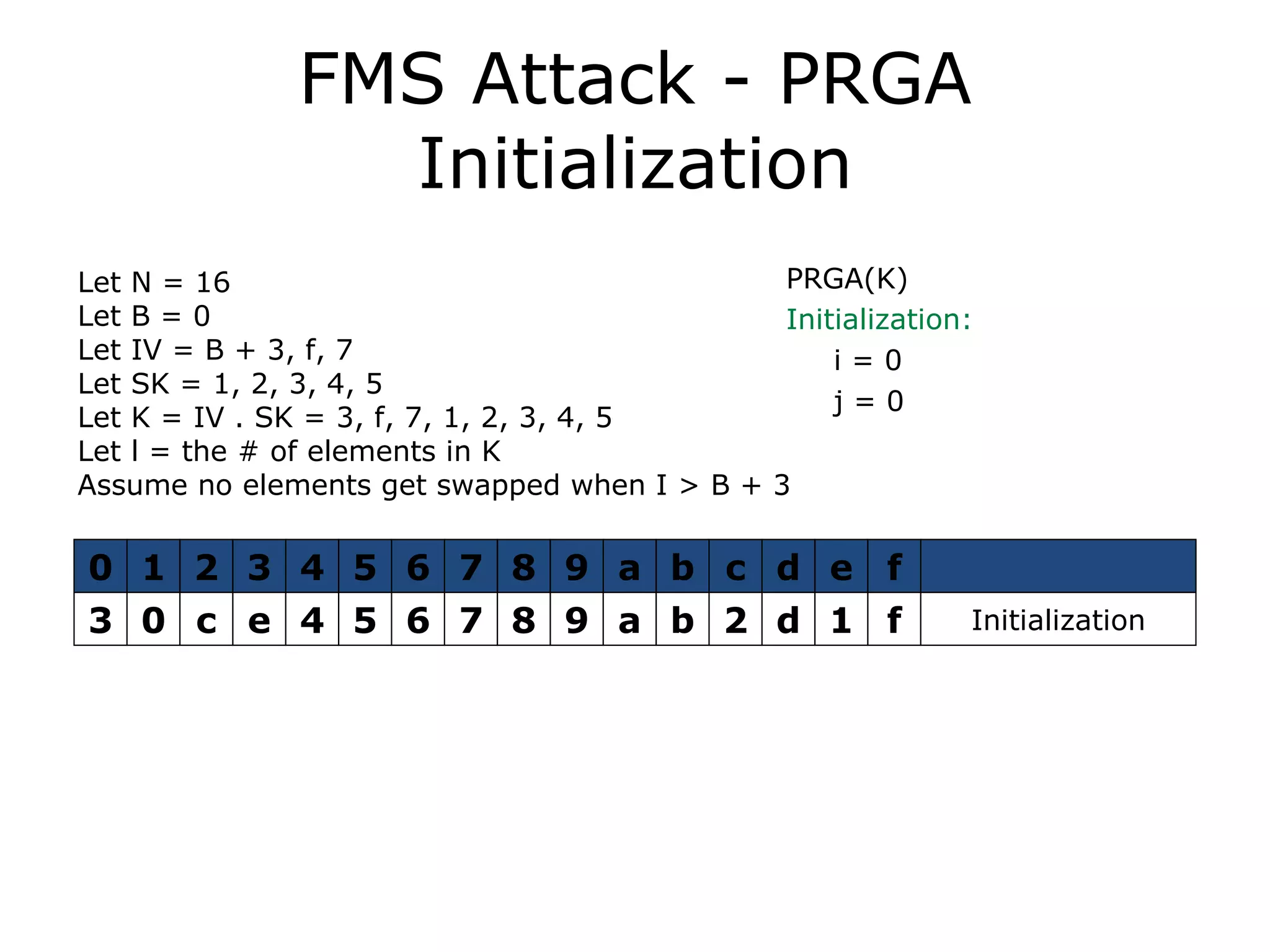

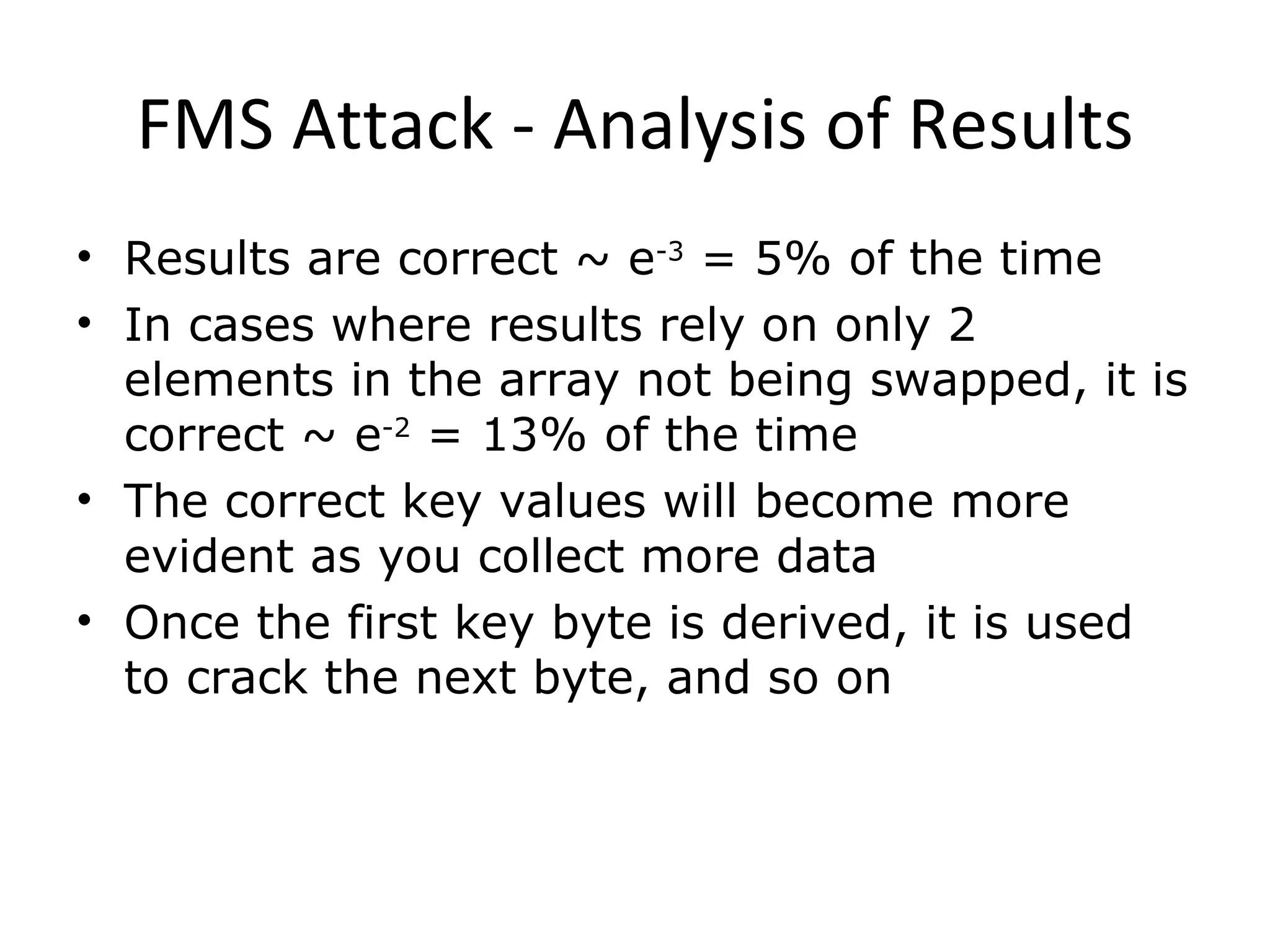

The document discusses weaknesses in the WEP encryption protocol used for securing 802.11 wireless networks. It describes how the reuse of initialization vectors (IVs) and certain "weak" IV values can allow attackers to decrypt packets and eventually recover the encryption key with only passive eavesdropping and a large number of intercepted packets. It also outlines attacks such as modifying encrypted packets to influence decrypted plaintext without knowing the key.

![WEP Data Transmission 802.11b Header IV[0] IV[1] IV[2] Key ID SNAP[0] SNAP[1] SNAP[2] SNAP[3] 32-bit Checksum Payload](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-7-2048.jpg)

![WEP Data Transmission IV[0] IV[1] IV[2] SK[0] SK[4] SK[3] SK[2] SK[1] K = IV . SK](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-8-2048.jpg)

![RC4 Fluhrer, Mantin, Shamir Attack Key Scheduling Algorithm Sets up RC4 state array S S is a permutation of 0, 1, … 255 Output generator uses S to create a pseudo-random sequence. First byte of output is given by S[S[1]+S[S[1]]]. First byte depends on {S[1], S[S[1], S[S[1]+S[S[1]]}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-18-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - RC4 Algorithms KSA(K) Initialization: For i = 0 .. N - 1 S[i] = i j = 0 Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) PRGA(K) Initialization: i = 0 j = 0 Generation Loop: i = i + 1 j = j + S[i] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Output z = S[S[i] + S[j]]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-21-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Initialization KSA(K) Initialization: For i = 0 .. N - 1 S[i] = i j = 0 Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-32-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Scrambling KSA(K) Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3 , f, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization 3 0 i=0, j= 0 + 0 + 3 =3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-33-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Scrambling KSA(K) Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f , 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization 3 0 i=0, j=0+0+3= 3 0 1 i=1, j= 3 + 1 + f =3](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-34-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Scrambling KSA(K) Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7 , 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization 3 0 i=0, j=0+0+3=3 0 1 i=1, j=3+1+f= 3 c 2 i=2, j= 3 + 2 + 7 =c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-35-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Scrambling KSA(K) Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1 , 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7, 1 , 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization 3 0 i=0, j=0+0+3=3 0 1 i=1, j=3+1+f=3 c 2 i=2, j=3+2+7= c 5 1 i=3, j= c + 1 + 1 =e Note that S[B+3] contains information relating to SK[B], since SK[B] is used to calculate j](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-36-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Scrambling KSA(K) Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7, 1 , 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization 3 0 i=0, j=0+0+3=3 0 1 i=1, j=3+1+f=3 c 2 i=2, j=3+2+7= c 3 0 c e 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b 2 d 1 f Done with KSA e 1 i=3, j= c + 1 + 1 =e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-37-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - PRGA Generation Loop PRGA(K) Generation Loop: i = i + 1 j = j + S[i] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Output z = S[ S[i] + S[j] ] Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 3 0 c e 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b 2 d 1 f Initialization 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 3 i=1, j= 0 + 0 =0, z=S[ 3 + 0 ]=e e is the output for the first byte](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-39-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - PRGA Generation Loop PRGA(K) Generation Loop: i = i + 1 j = j + S[i] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Output z = S[ S[i] + S[j] ] Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 3 0 c e 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b 2 d 1 f Initialization 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 3 i=1, j= 0 + 0 =0, z=S[ 3 + 0 ]=e e is the output for the first byte e is then xor’ed with the first byte of data, which is always 0xaa on ip networks](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-40-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Scrambling KSA(K) Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization 3 0 i=0, j=0+0+3=3 0 1 i=1, j=3+1+f=3 c 2 i=2, j=3+2+7=c 3 0 c e 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b 2 d 1 f Done with KSA e 1 i=3, j=c+1+1=e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-41-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - KSA Scrambling KSA(K) Scrambling: For i = 0 .. N - 1 j = j + S[i] + K[i mod l] Swap(S[i], S[j]) Let N = 16 Let B = 0 Let IV = B + 3, f, 7 Let SK = 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let K = IV . SK = 3, f, 7, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 Let l = the # of elements in K Assume no elements get swapped when I > B + 3 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f Initialization 3 0 i=0, j=0+0+3=3 0 1 i=1, j=3+1+f=3 c 2 i=2, j=3+2+7= c 3 0 c e 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b 2 d 1 f Done with KSA e 1 i=3, j= c + 1 +1=e](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-42-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - Reversing Output to Key Byte S -1 [X] is the location of X in S SK[B] = S -1 [Out] - j - S[i + 1] SK[B] = S -1 [e] - c - 1 = 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-43-2048.jpg)

![FMS Attack - Detection of Weak IVs How do you find IV’s that setup S so that it reveals key information? Baseline attack is to look for IV’s that conform to: (A + 3, N - 1, X) But is recommended that you use the following equations right after the KSA: X = S B+3 [1] < B+3 X + S B+3 [X] = B+3 The main dilemma is that this equation is dependent on the previous key bytes, so it has to be applied to the entire sample set for every key byte that is tried](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/wififinal-120223221357-phpapp01/75/Wepwhacker-45-2048.jpg)