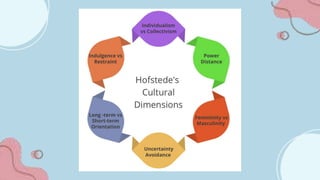

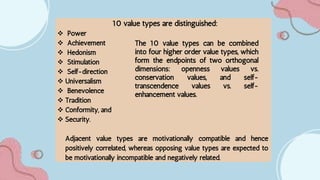

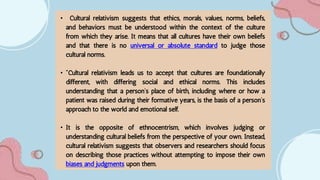

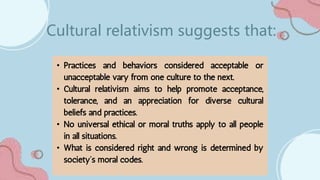

Cultural values differ between countries in important ways. Hofstede's cultural dimensions theory identifies six dimensions that describe cultural variations: power distance, individualism vs collectivism, masculinity vs femininity, uncertainty avoidance, long-term vs short-term orientation, and indulgence vs restraint. While values like equality may be universally important, behaviors seen as exemplifying values can differ cross-culturally. Understanding these cultural differences in communication styles and value priorities is important for improving intercultural relationships.