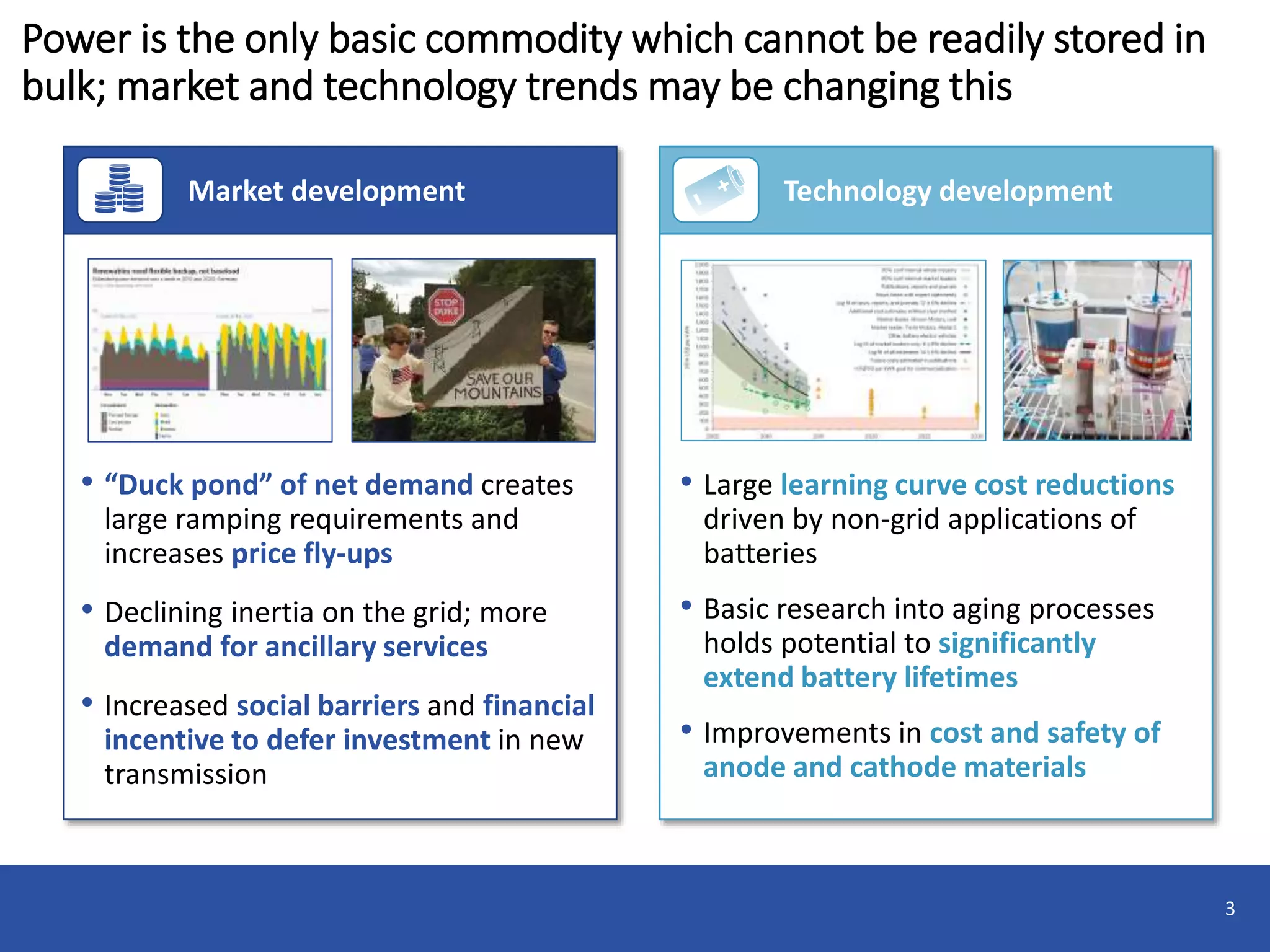

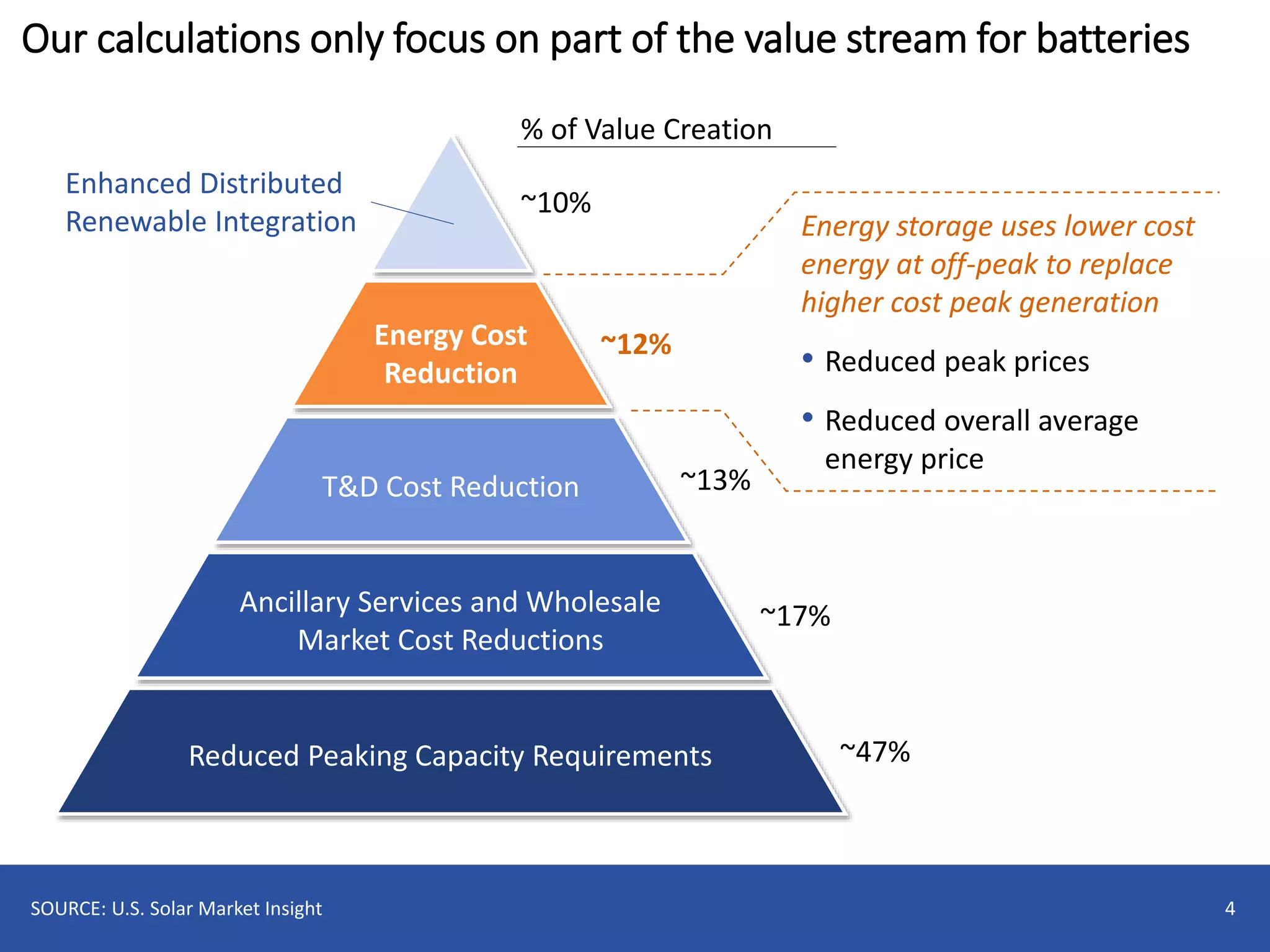

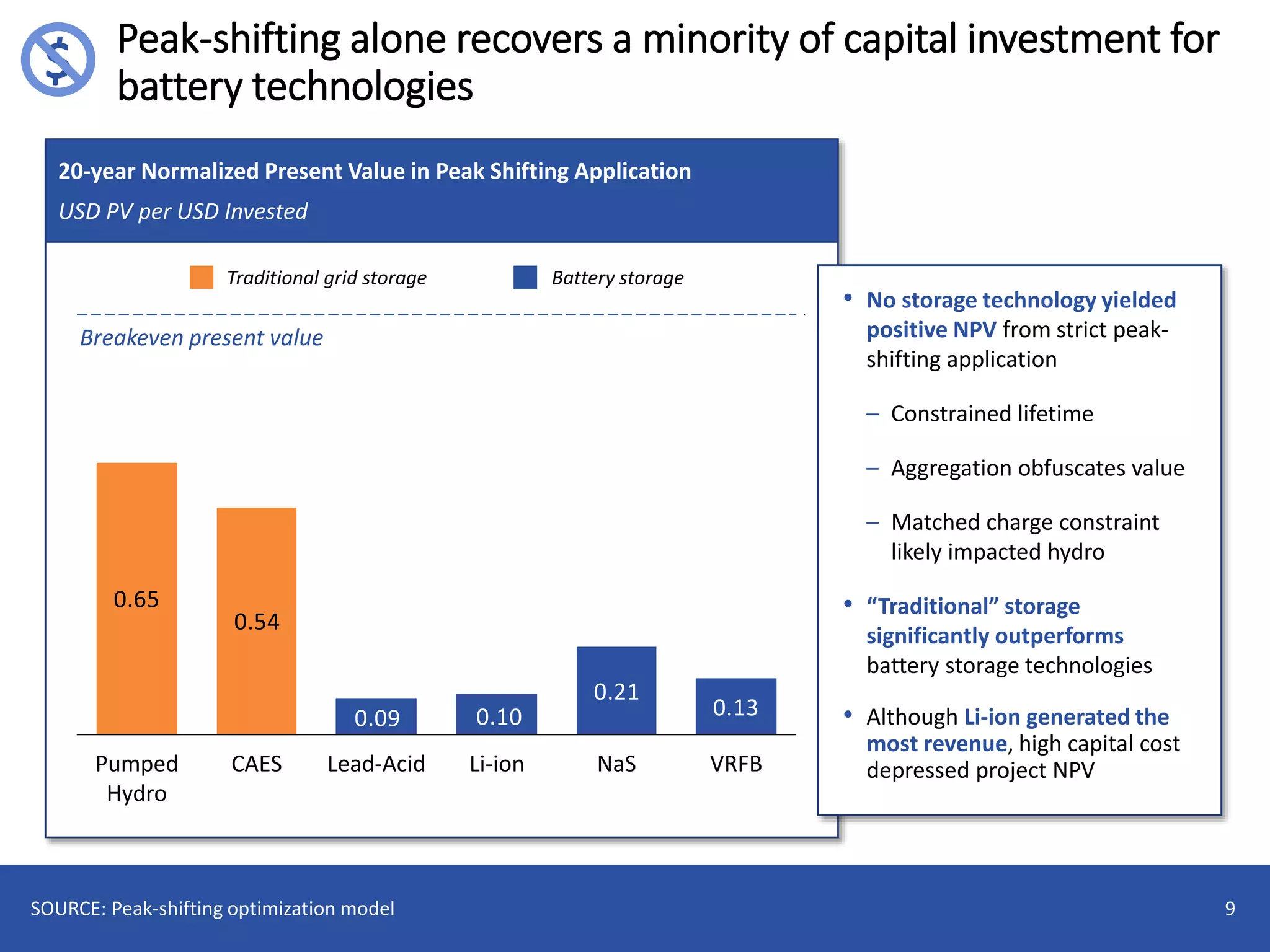

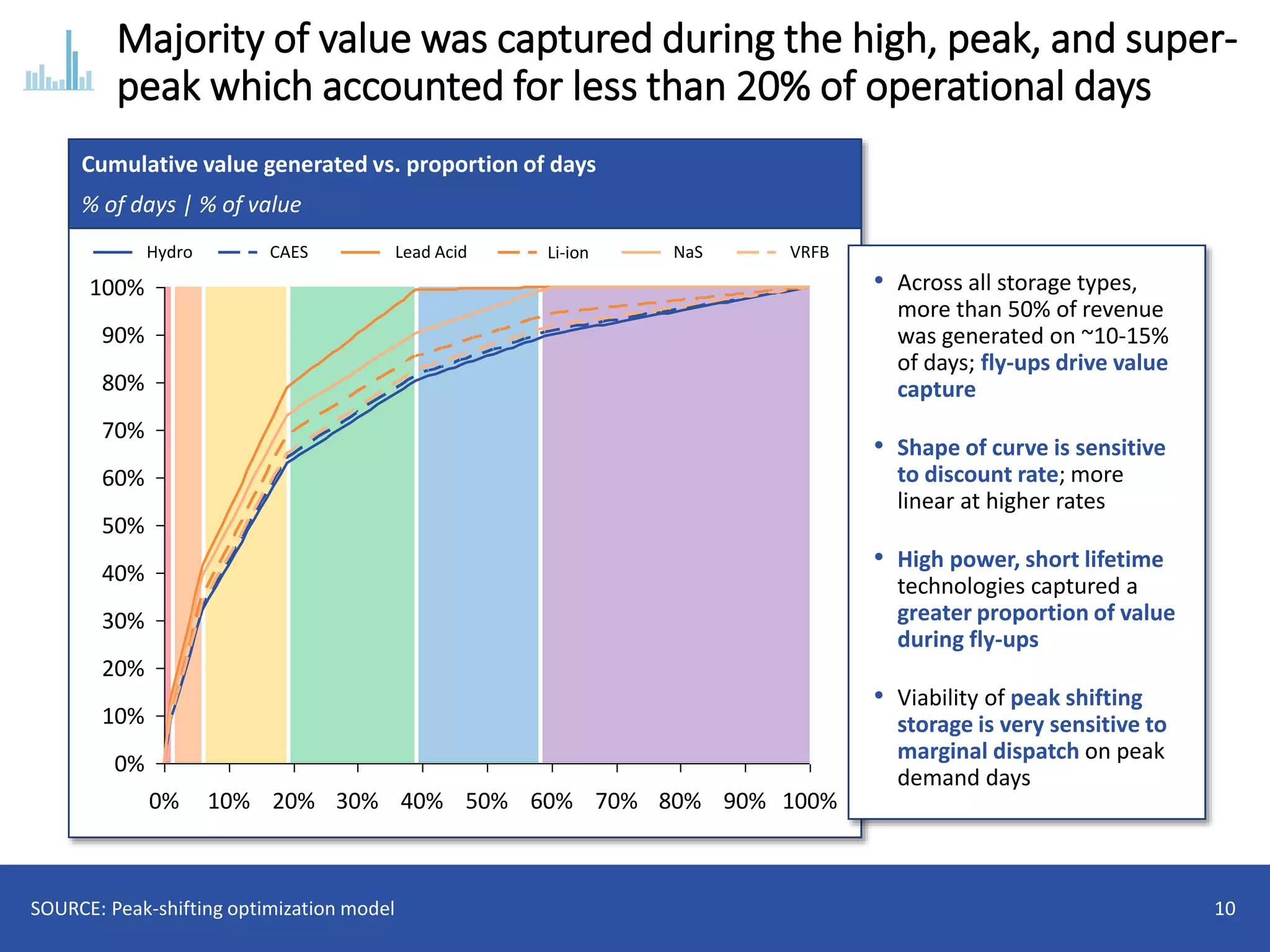

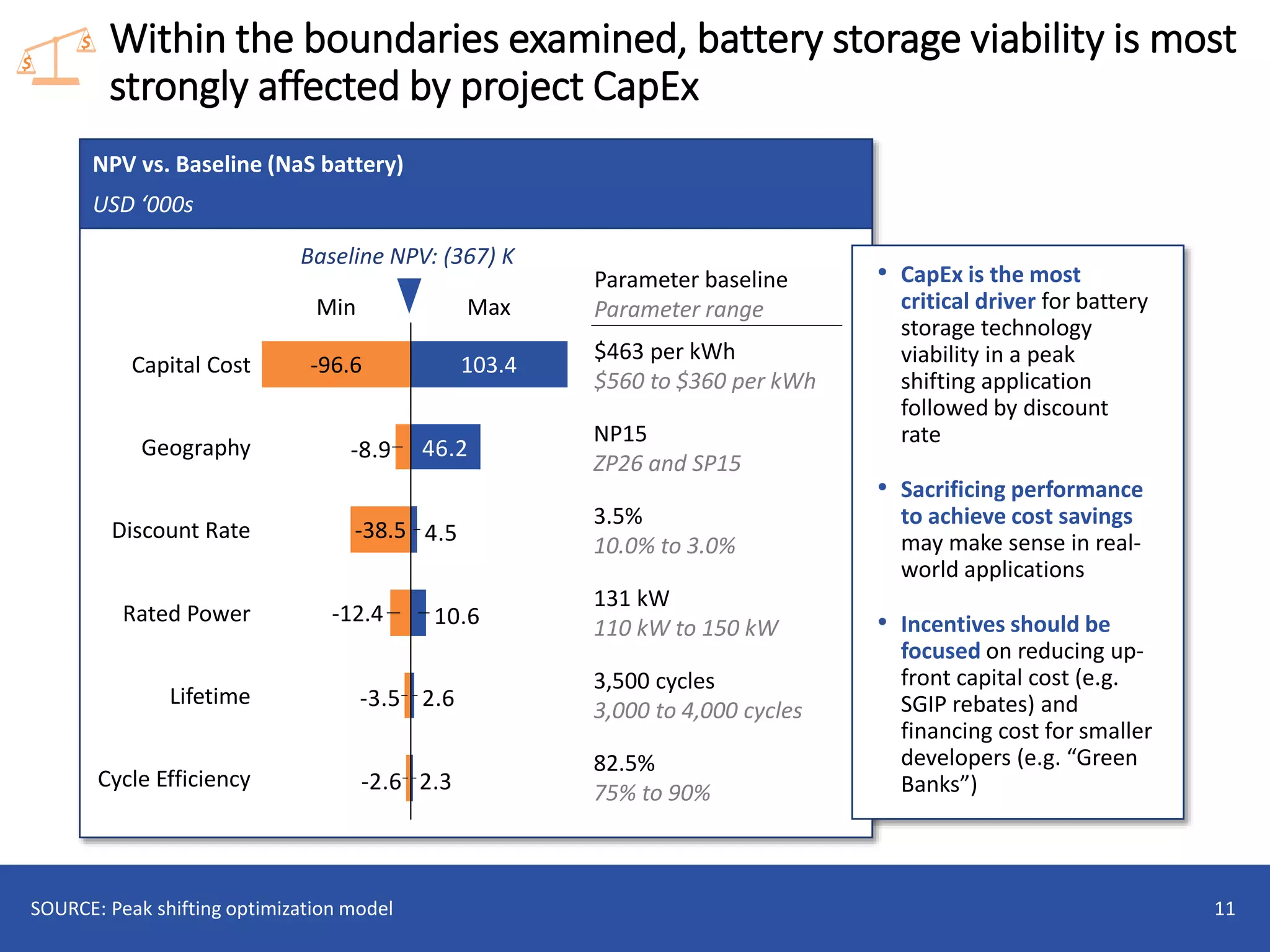

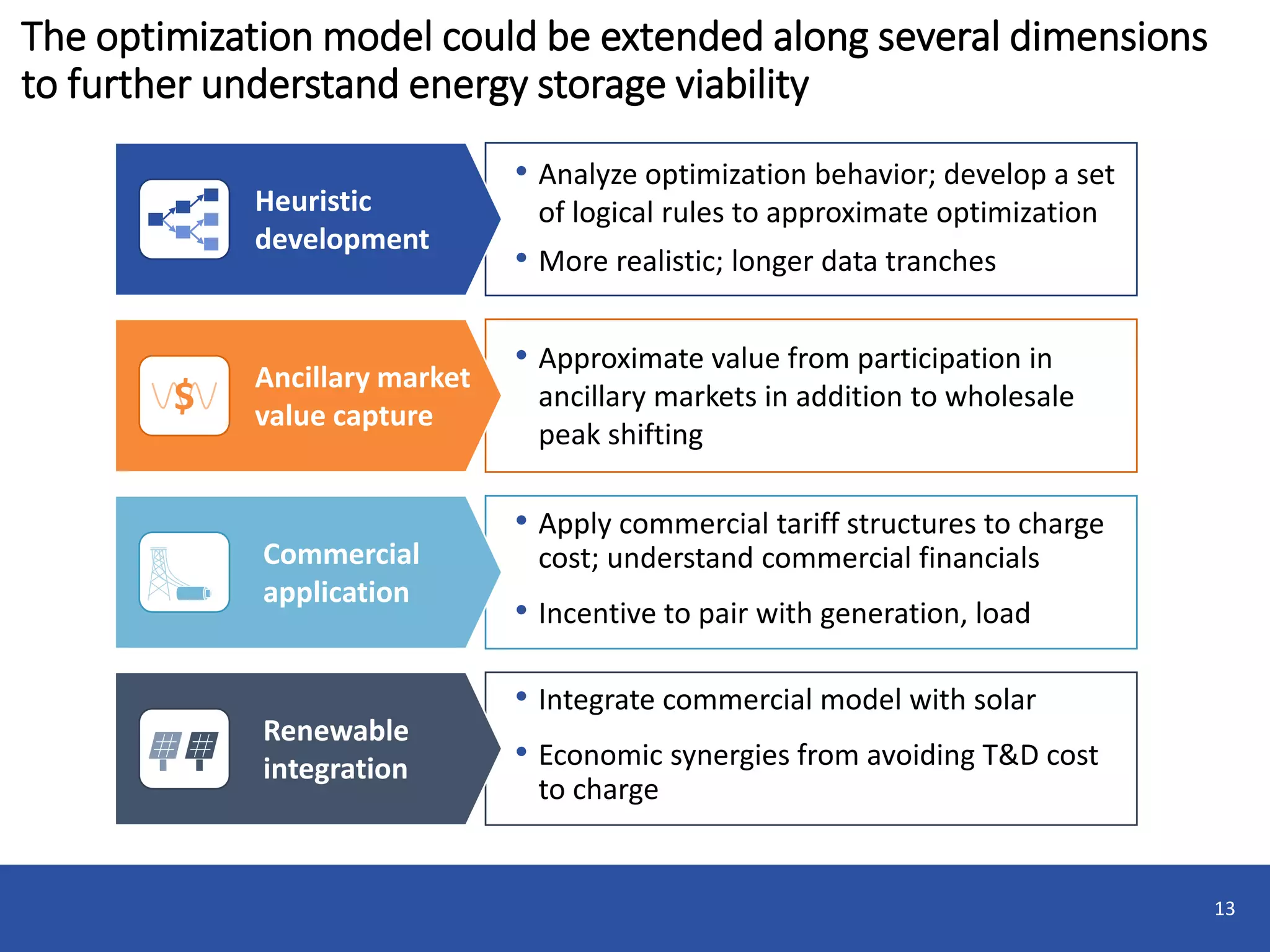

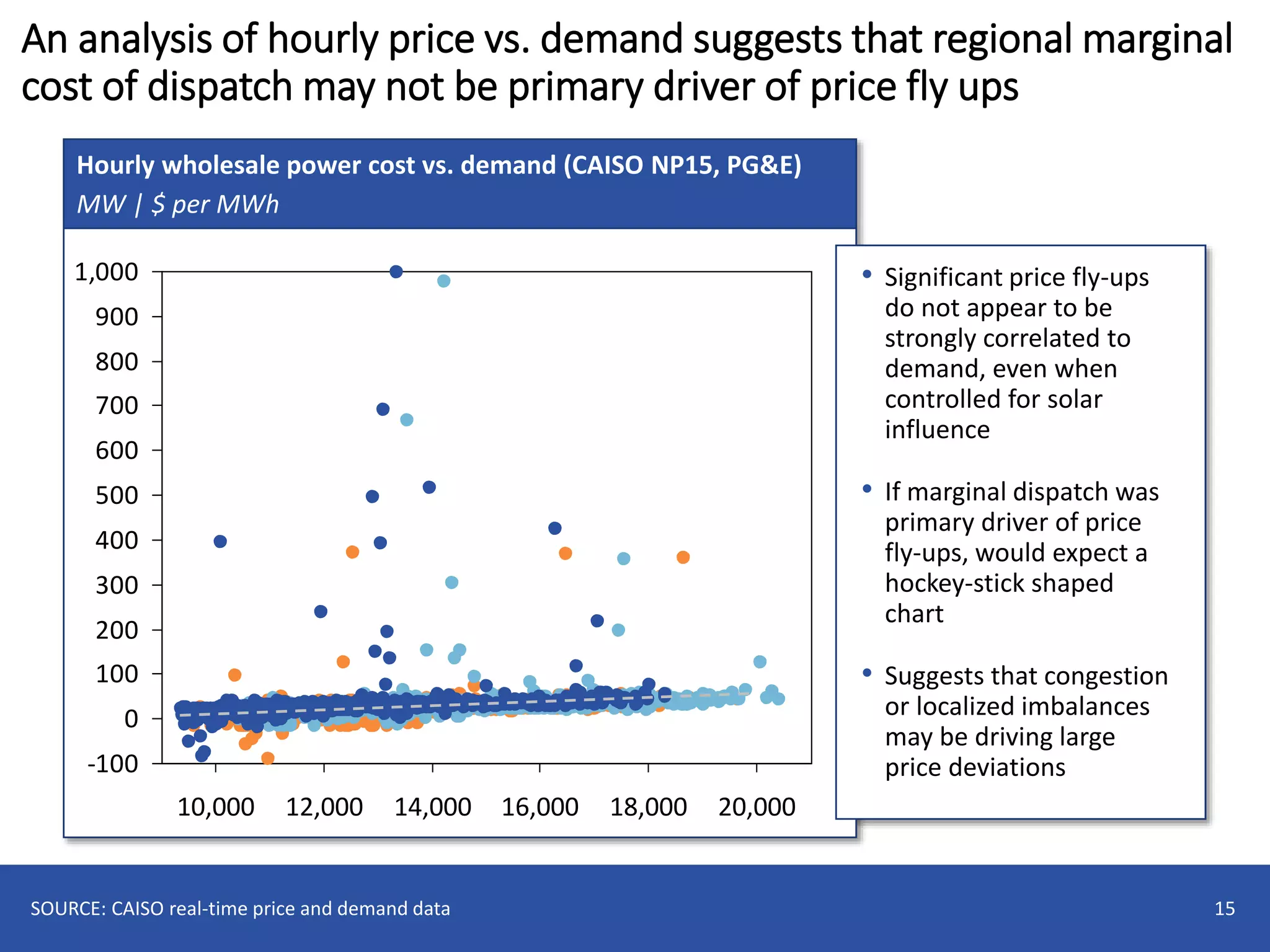

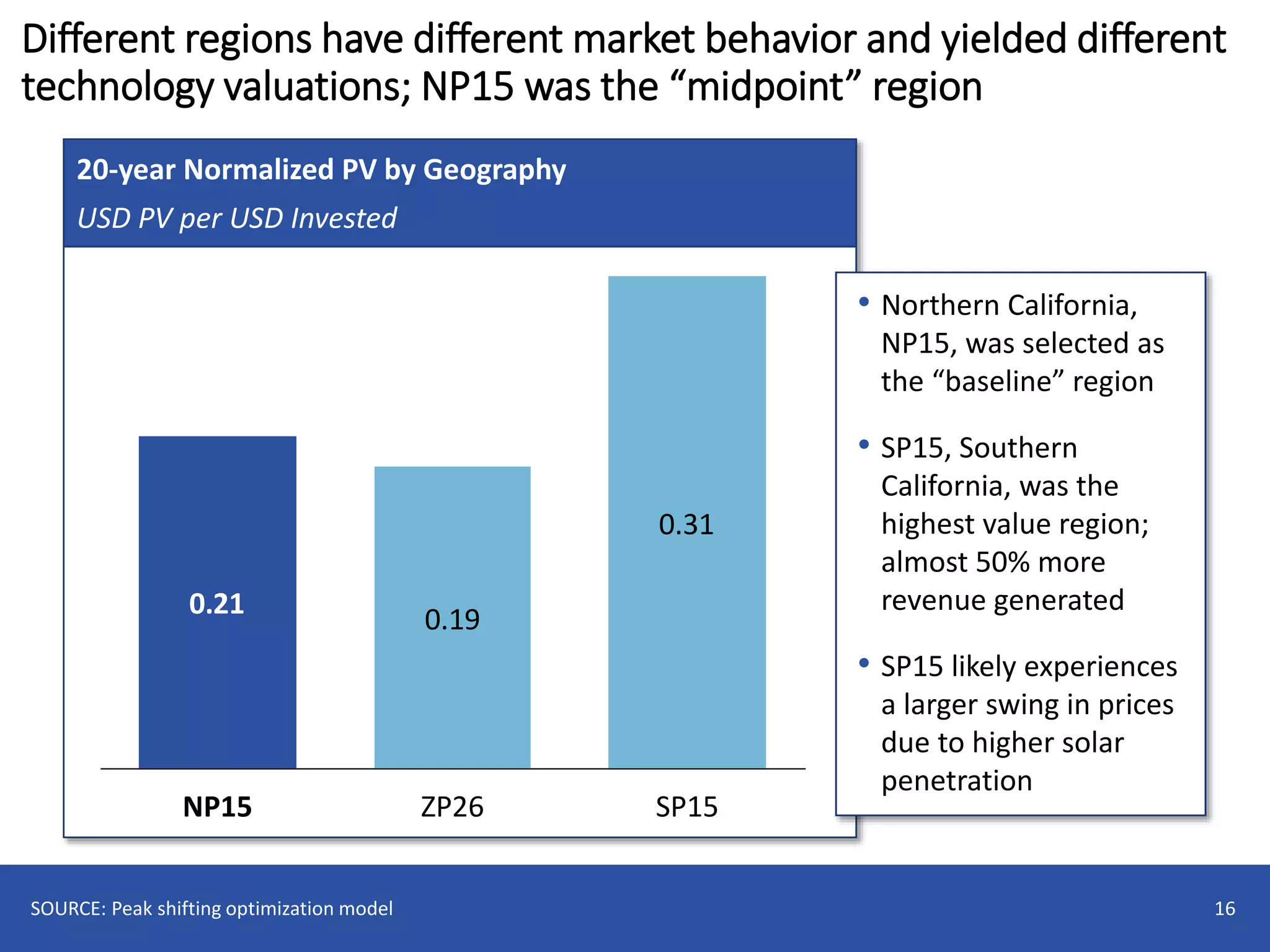

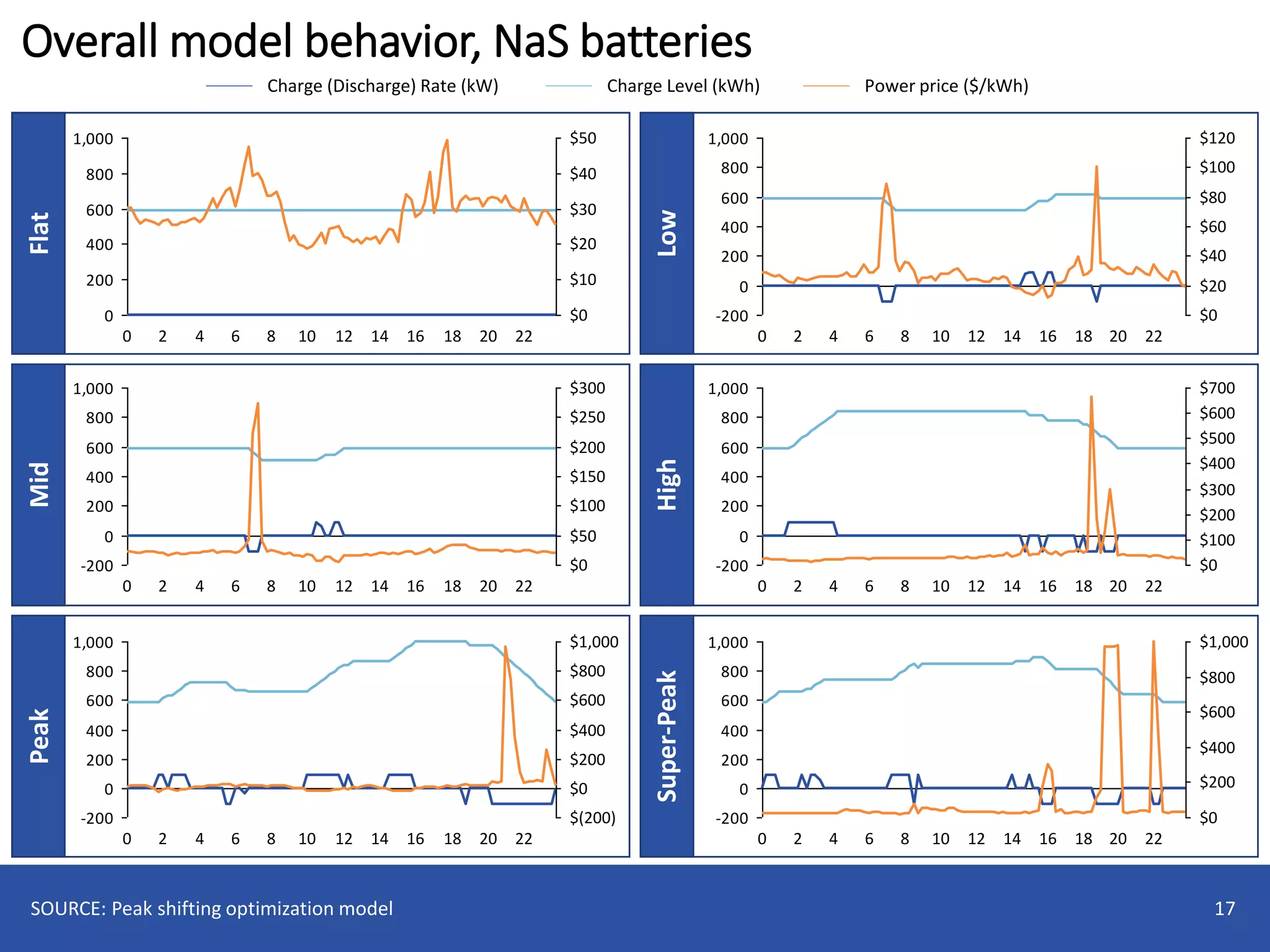

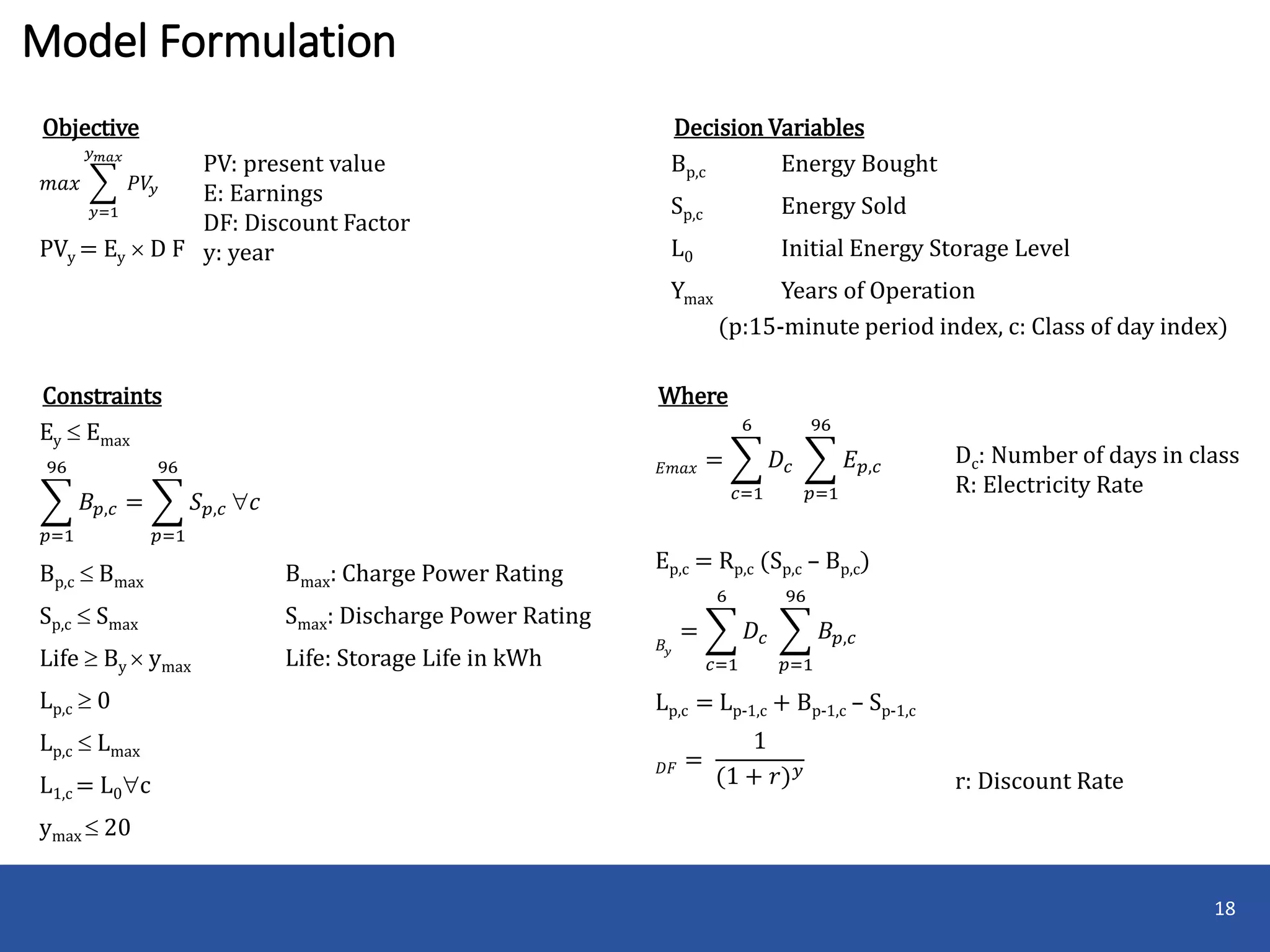

The document evaluates the valuation of energy storage in peak shifting applications, highlighting market and technology trends that could impact storage viability. An optimization model shows that peak-shifting alone does not yield sufficient value to justify storage investments, with significant revenue generation occurring only on a limited number of high-demand days. It emphasizes the criticality of capital costs and the potential of incentives to improve battery storage feasibility in specific regional contexts.