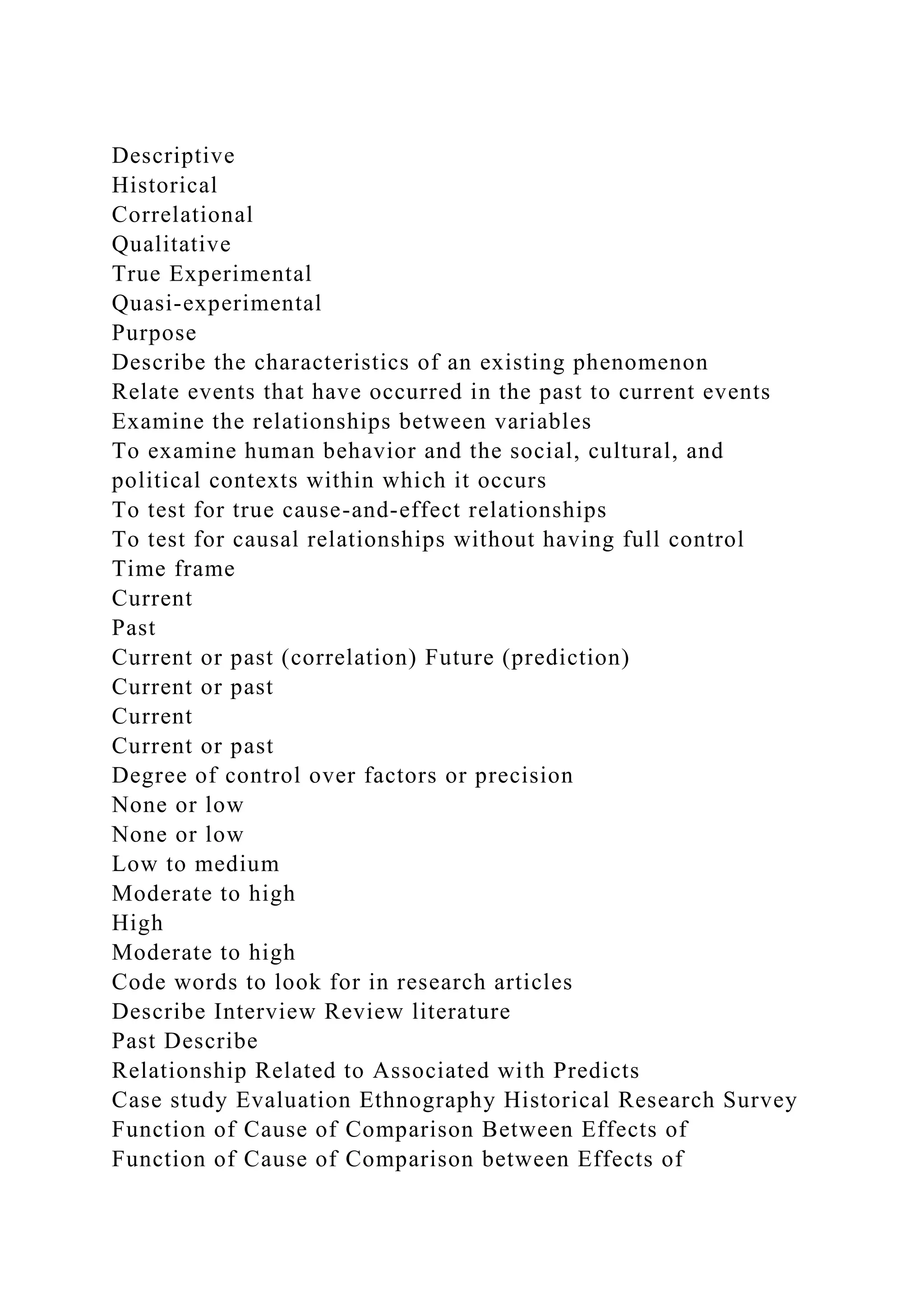

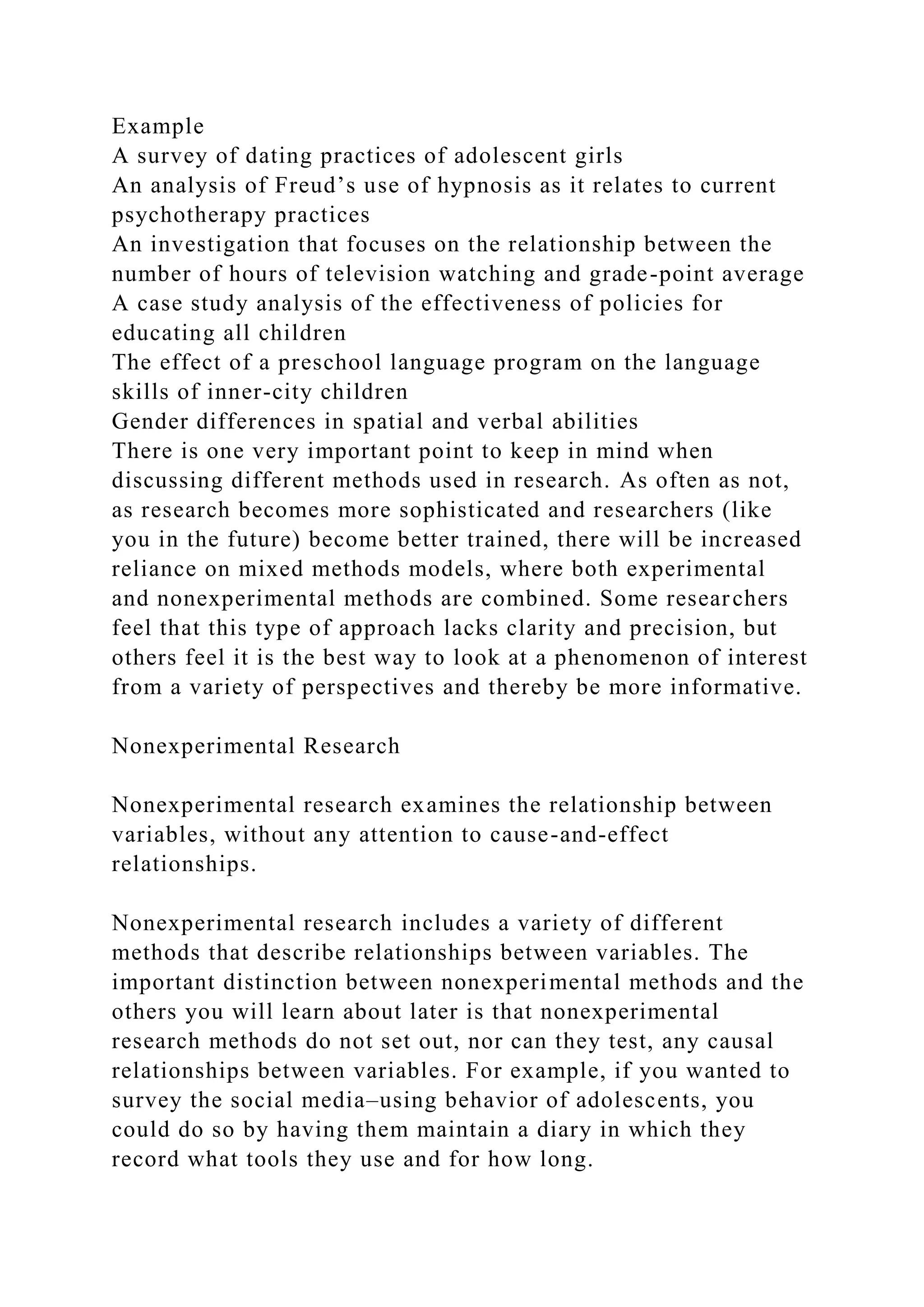

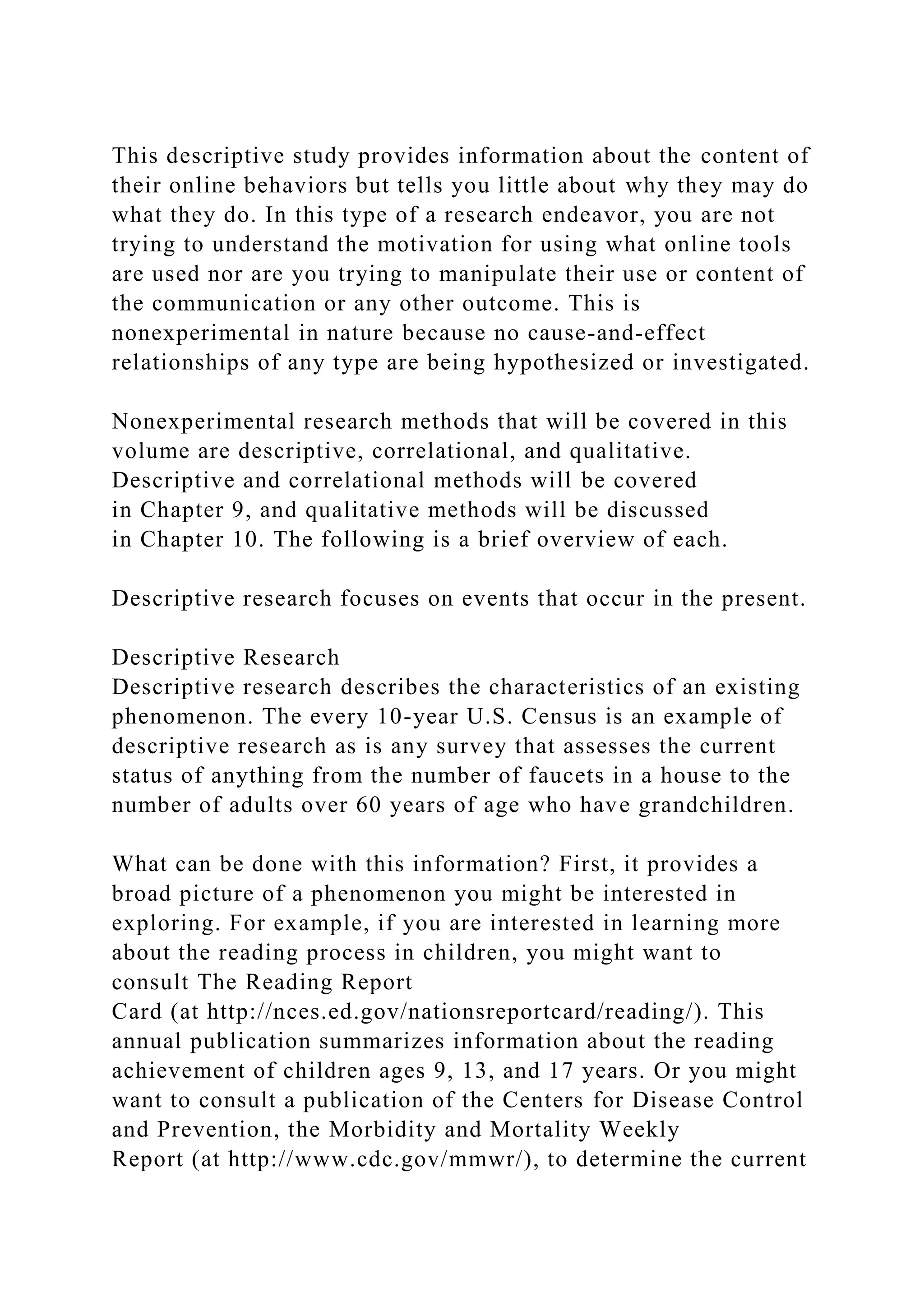

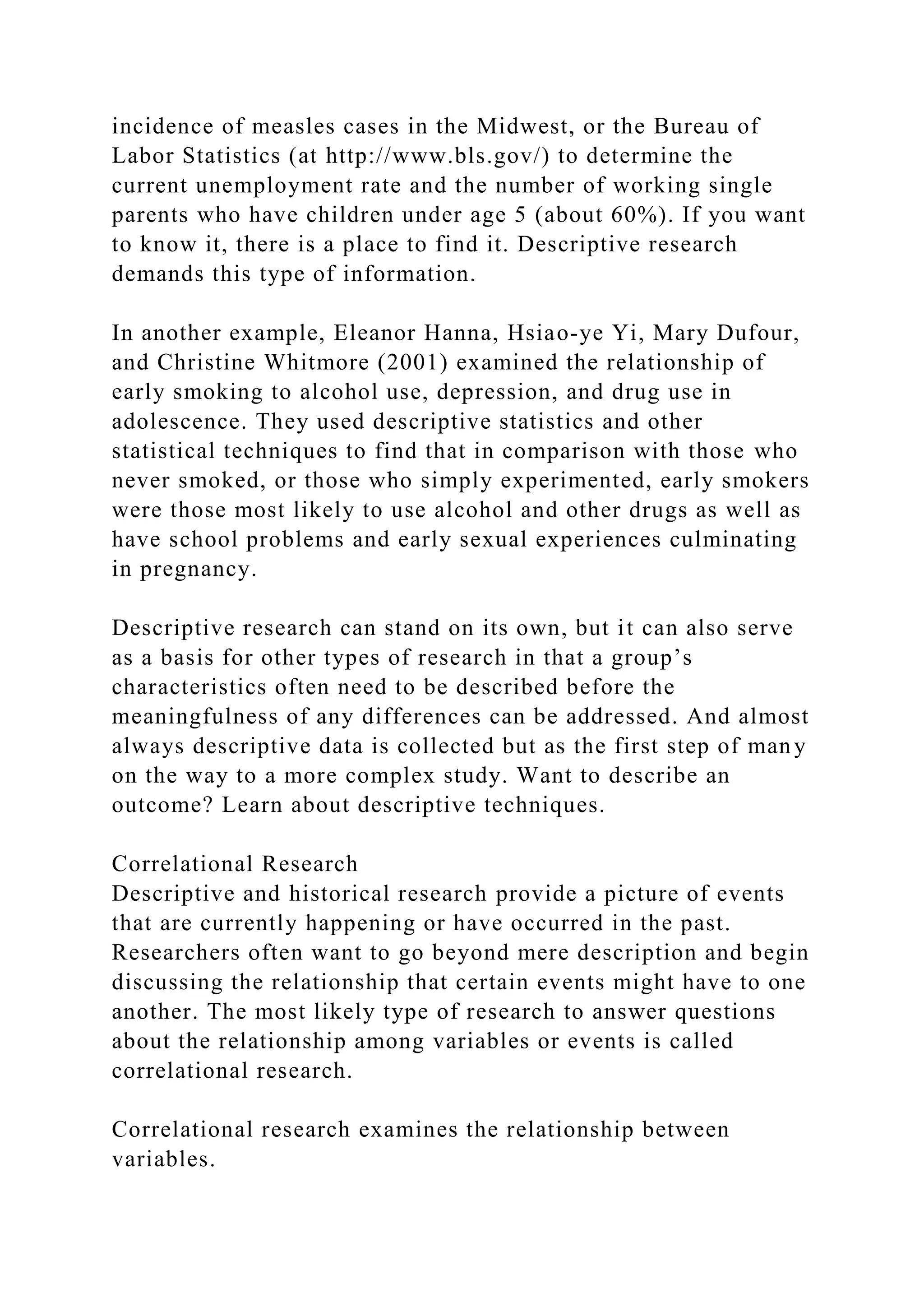

The document outlines the fundamental aspects of research, emphasizing the importance of understanding research design and methods. It introduces key concepts regarding what constitutes good research, including its basis on existing work, replicability, generalizability, and the ethical considerations involved in seeking knowledge for societal betterment. Moreover, it highlights the cyclical and incremental nature of research and presents a model of scientific inquiry as a structured approach to answering questions related to human behavior.