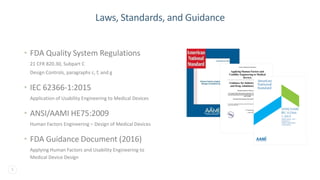

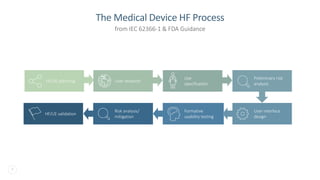

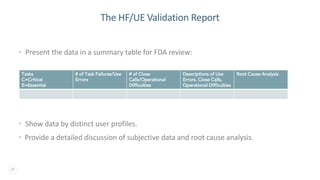

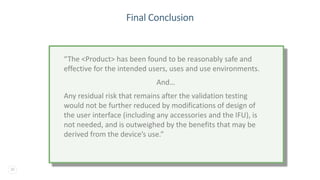

The document discusses the critical importance of human factors (HF) in the usability testing of medical devices and software, highlighting regulatory requirements from the FDA and IEC standards. It outlines the HF process, which includes user research, interface design, formative testing, and validation to ensure safety and effectiveness. Furthermore, it emphasizes the need for comprehensive testing conditions and user profiles to mitigate risks associated with medical device use.