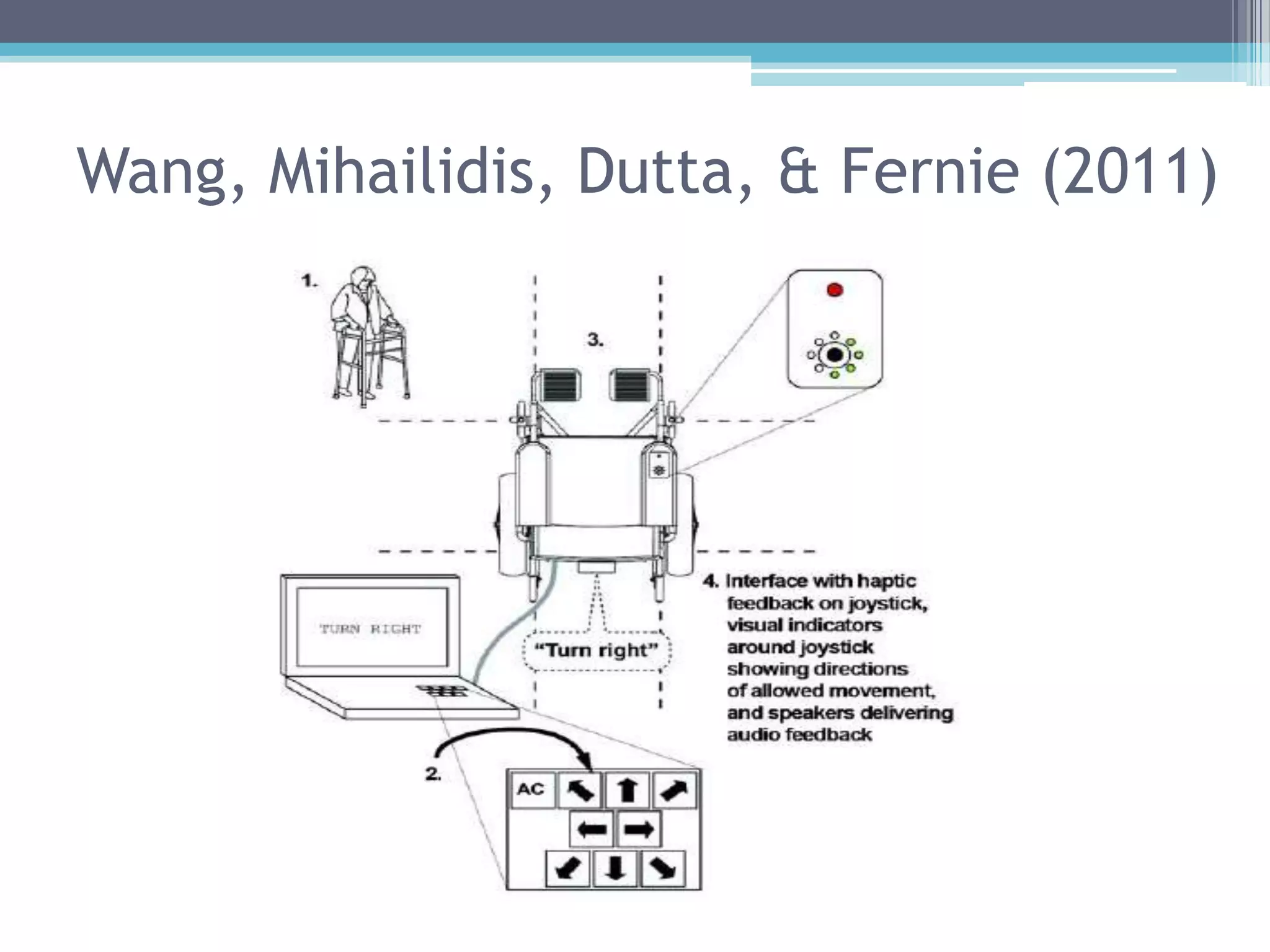

The document discusses usability testing for older adults and technology. It describes some of the physical and cognitive changes that occur with aging and how this impacts older adults' ability and willingness to use technology. Two research studies are summarized: Hart et al. (2008) evaluated websites' compliance with senior-friendly guidelines and how this impacted older users' task success. Wang et al. (2011) conducted usability testing of a power wheelchair with collision avoidance features with older adults, who found the device effective and provided feedback for improvement. The document emphasizes the importance of usability testing technology with the target older adult user group.