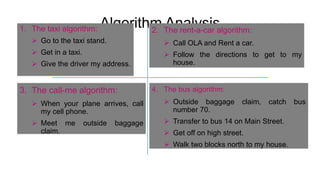

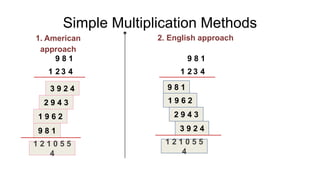

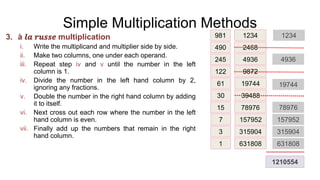

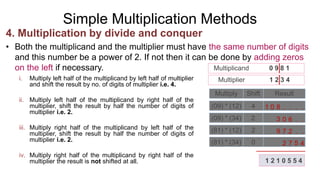

The document discusses various topics related to algorithms including algorithm design, real-life applications, analysis, and implementation. It specifically covers four algorithms - the taxi algorithm, rent-a-car algorithm, call-me algorithm, and bus algorithm - for getting from an airport to a house. It also provides examples of simple multiplication methods like the American, English, and Russian approaches as well as the divide and conquer method.

![Properties of the Relation

• Reflexive: Let 𝐴 be a set, and let 𝑅 be a binary relation on 𝐴.

Relation 𝑅 is reflexive if,

Example 1

A = {1, 2} and R1 = {(a, b) | a ≤ b}

so, R1 = 1,1 , 1,2 , 2,2

B = 1,2,3 , and

R2 = {(1,1), (1,2), (2,1), (2,2), (3,1)}

Example 2

Reflexive

Not Reflexive since (𝟑, 𝟑) ∉

𝑹

∀𝒙: [(𝒙 ∈ 𝑨) → ((𝒙, 𝒙) ∈ 𝑹)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1basicconceptofalgorithm-221109084536-a2fd0577/85/Unit-1-Basic-Concept-of-Algorithm-pptx-29-320.jpg)

![Properties of the Relation

• Symmetric: A relation 𝑅 on a set 𝐴 is called symmetric if

(𝑦, 𝑥) ∈ 𝑅 whenever (𝑥, 𝑦) ∈ 𝑅, for some 𝑥, 𝑦 ∈ 𝐴.

Example 1

A = {1,2,3} and R1 = {(a, b)|a ≠ b}

R1 = {(1,2), (1,3), (2,1), (2,3), (3,1), (3,2)}

B = { 1, 2, 3} and R2 = {(a, b) | a ≤ b}

So, R2 = {(1,1), (1,2), (1,3), (2,2), (2,3), (3,3)}

Example 2

Symmetri

c

Asymmetri

c

∀𝒙: ∀𝒚: [((𝒙, 𝒚) ∈ 𝑹) → ((𝒚, 𝒙) ∈ 𝑹)]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1basicconceptofalgorithm-221109084536-a2fd0577/85/Unit-1-Basic-Concept-of-Algorithm-pptx-30-320.jpg)

![Properties of the Relation

• Transitive: A relation 𝑅 on a set 𝐴, is called transitive if

whenever (𝑥, 𝑦) ∈ 𝑅 and (𝑦, 𝑧) ∈ 𝑅, then (𝑥, 𝑧) ∈ 𝑅, for 𝑥, 𝑦, 𝑧 ∈

𝐴.

Example 1

A = { 1, 2, 3} and R1 = {(a, b) | a ≤ b}

So, R1 =

{(1,1), (1,2), (1,3), (2,2), (2,3), (3,3)}

B = 1, 2, 3,4 and

R2 = a, b | 𝑤ℎ𝑒𝑟𝑒 𝑏 𝑖𝑠 𝑎 𝑠𝑢𝑐𝑐𝑒𝑠𝑠𝑜𝑟 𝑜𝑓 𝑎

So, R2 = { 1,2 , 2,3 , (3,4)}

Example 2

Transitive

∀𝒙: ∀𝒚: ∀𝒛[([(𝒙, 𝒚) ∈ 𝑹] ∧ [(𝒚, 𝒛) ∈ 𝑹]) → ((𝒙, 𝒛) ∈ 𝑹)]

Not

Transitive](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/unit-1basicconceptofalgorithm-221109084536-a2fd0577/85/Unit-1-Basic-Concept-of-Algorithm-pptx-31-320.jpg)