1) The language of science needs to be precise, with terms clearly defined, and may involve mathematical language.

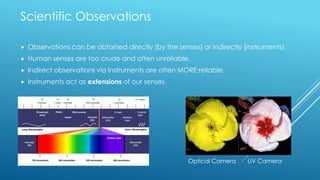

2) Observations can be made directly through senses or indirectly through instruments, which can provide more reliable data, acting as extensions of our senses. Quantitative data is preferred.

3) A hypothesis is an educated guess used to explain a phenomenon and make predictions to enable experimentation. Experiments are designed to test hypotheses by controlling variables, and hypotheses accumulate evidence or are modified or discarded based on results.