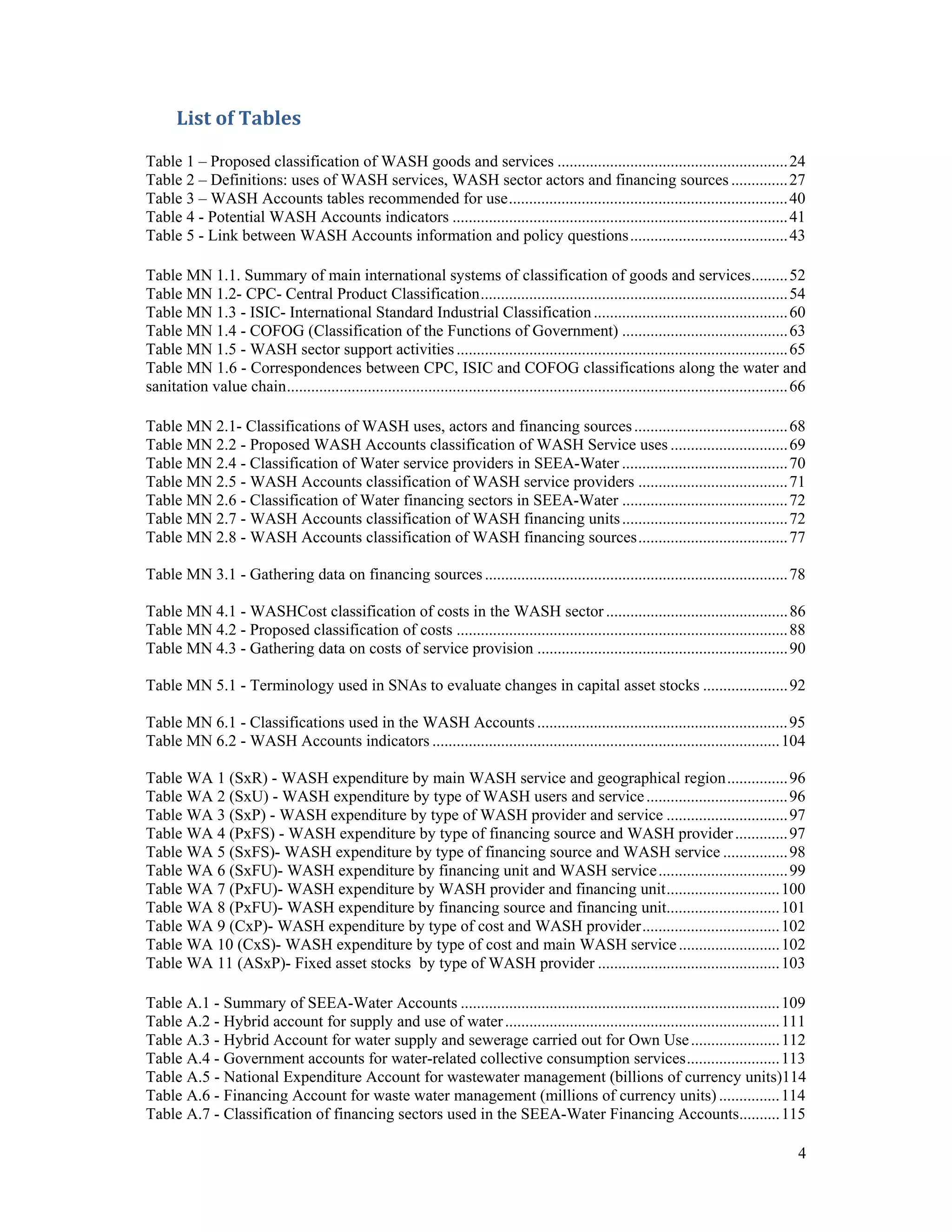

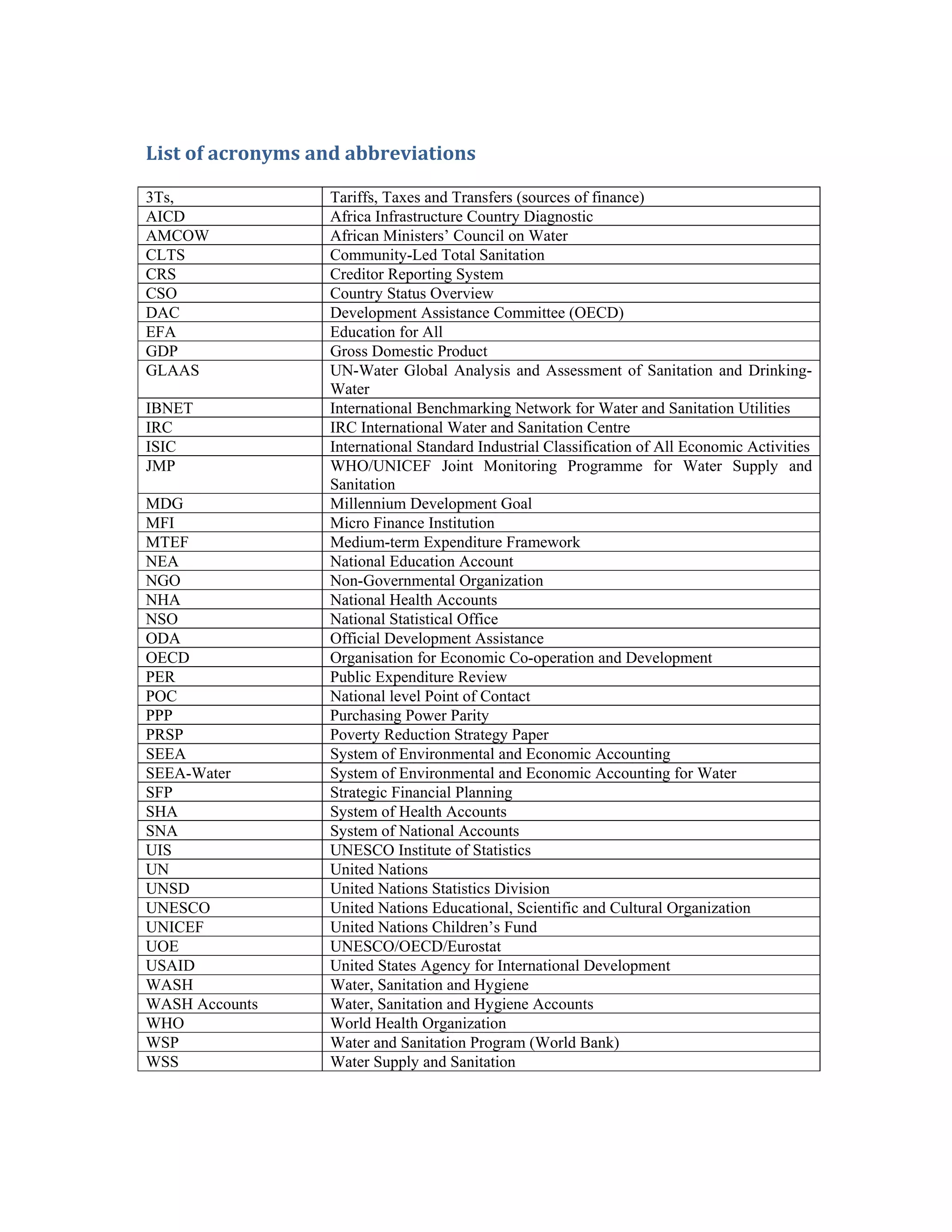

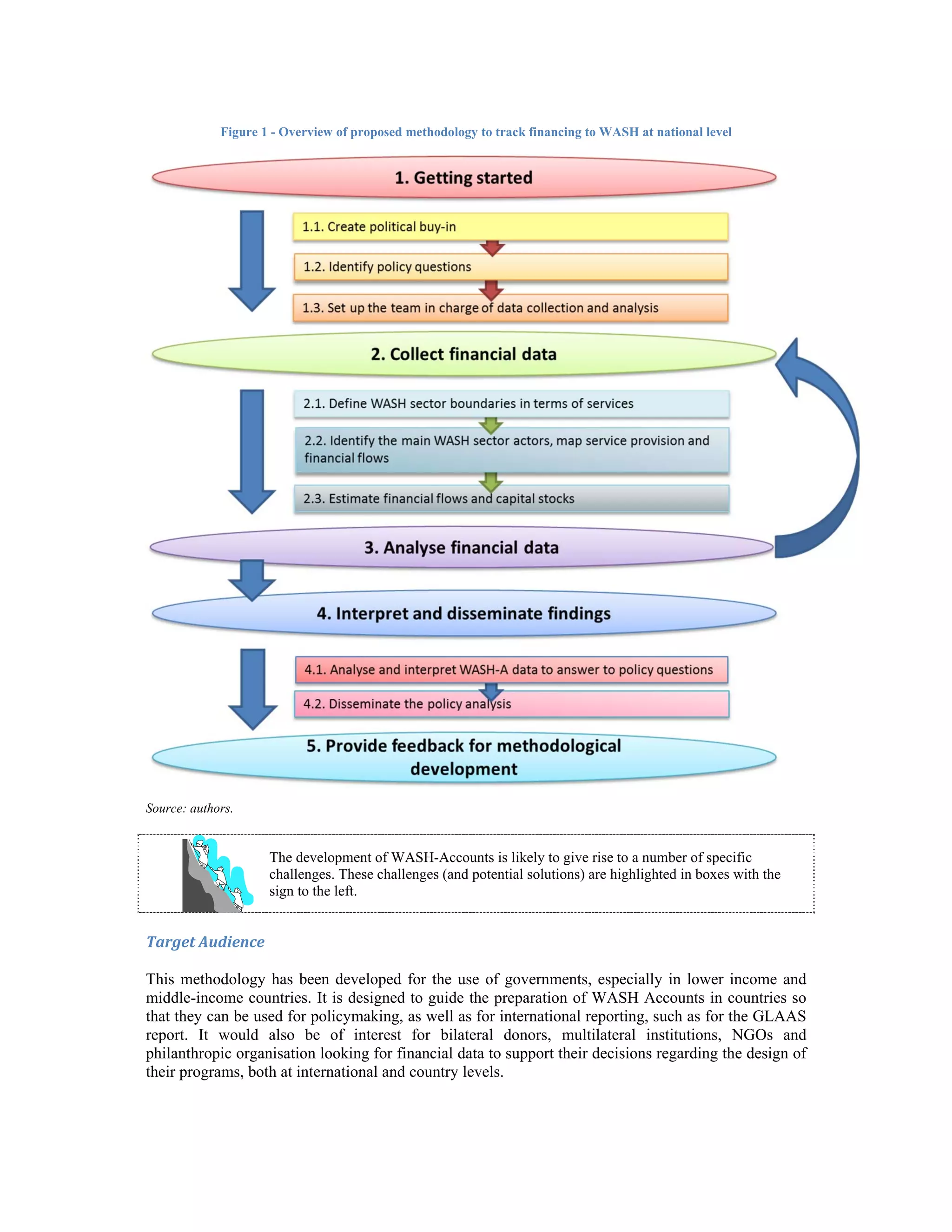

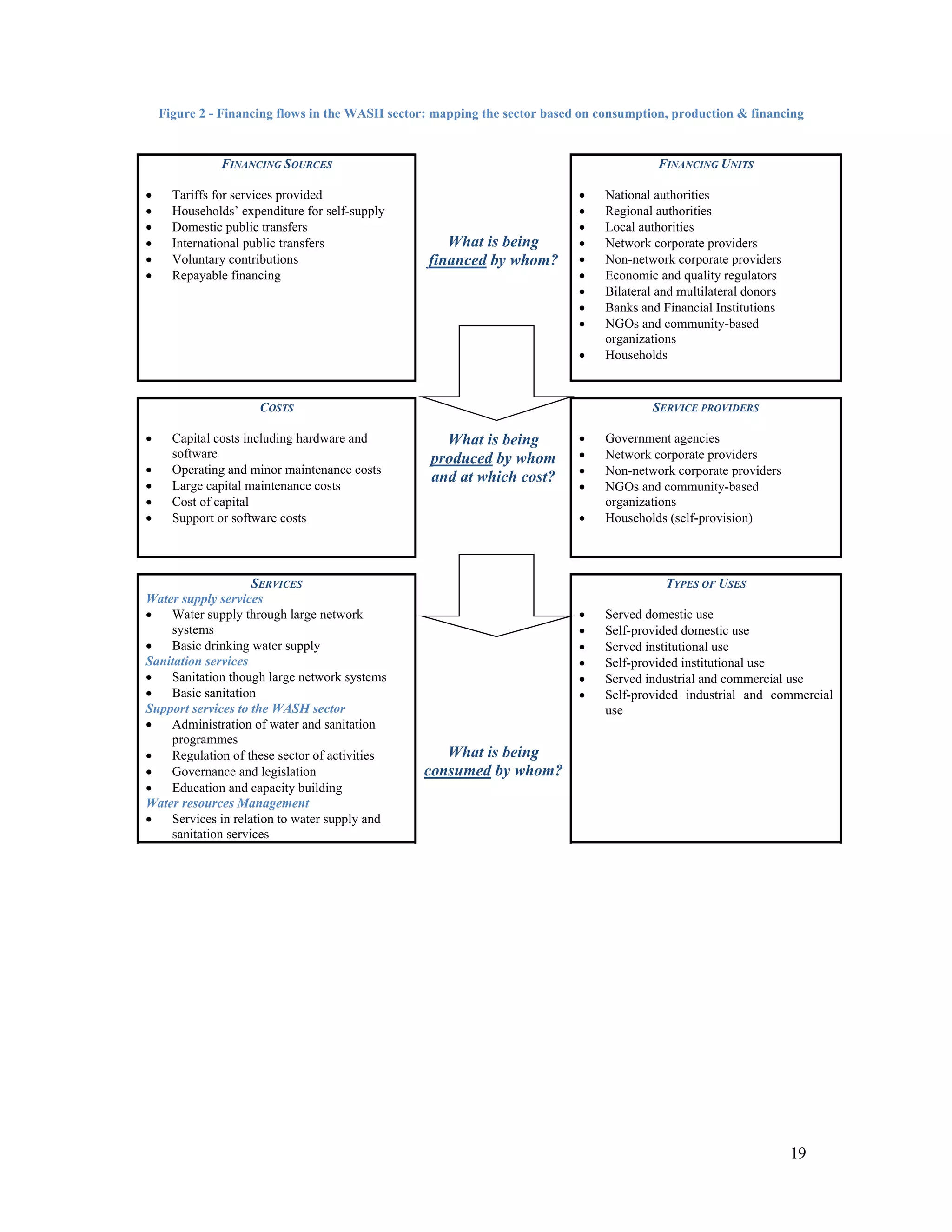

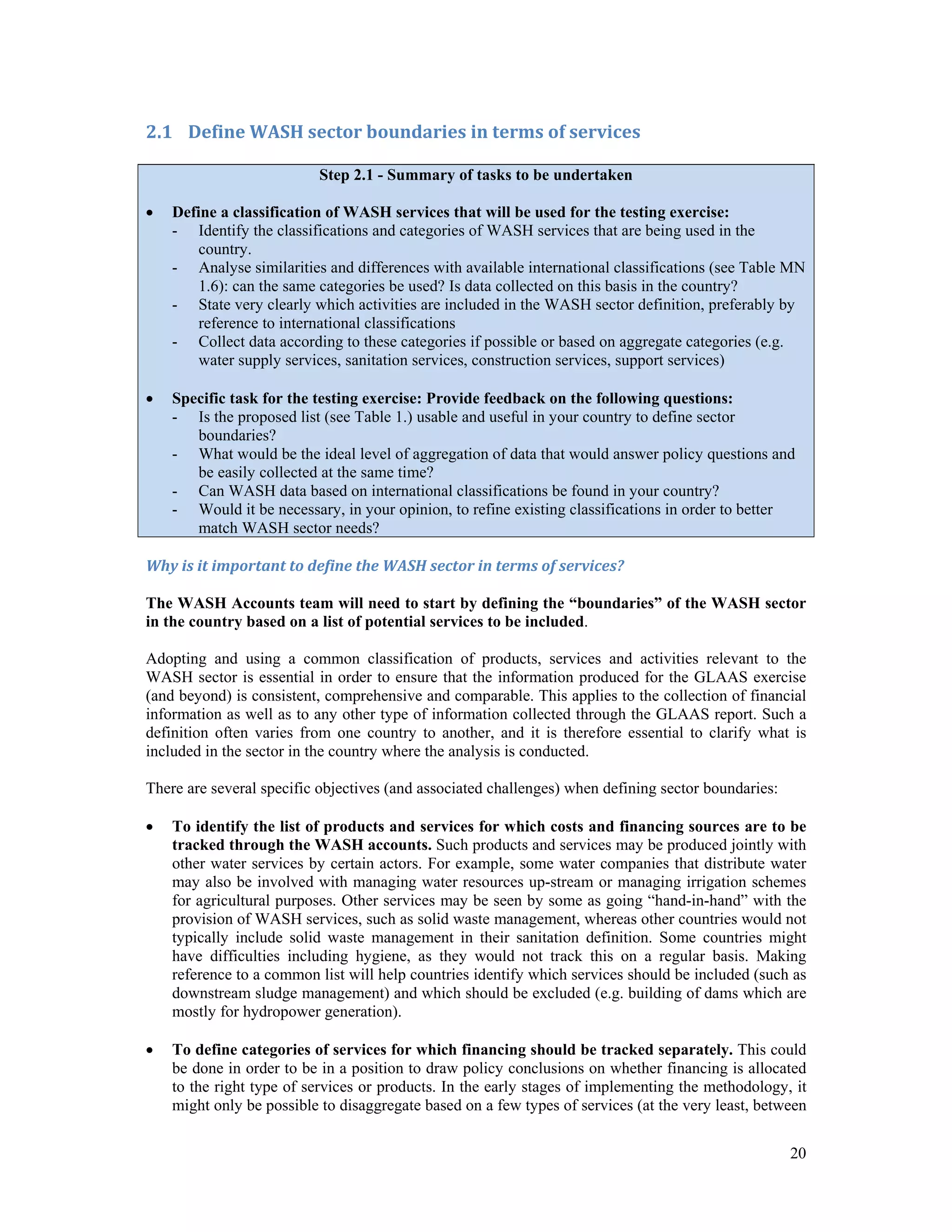

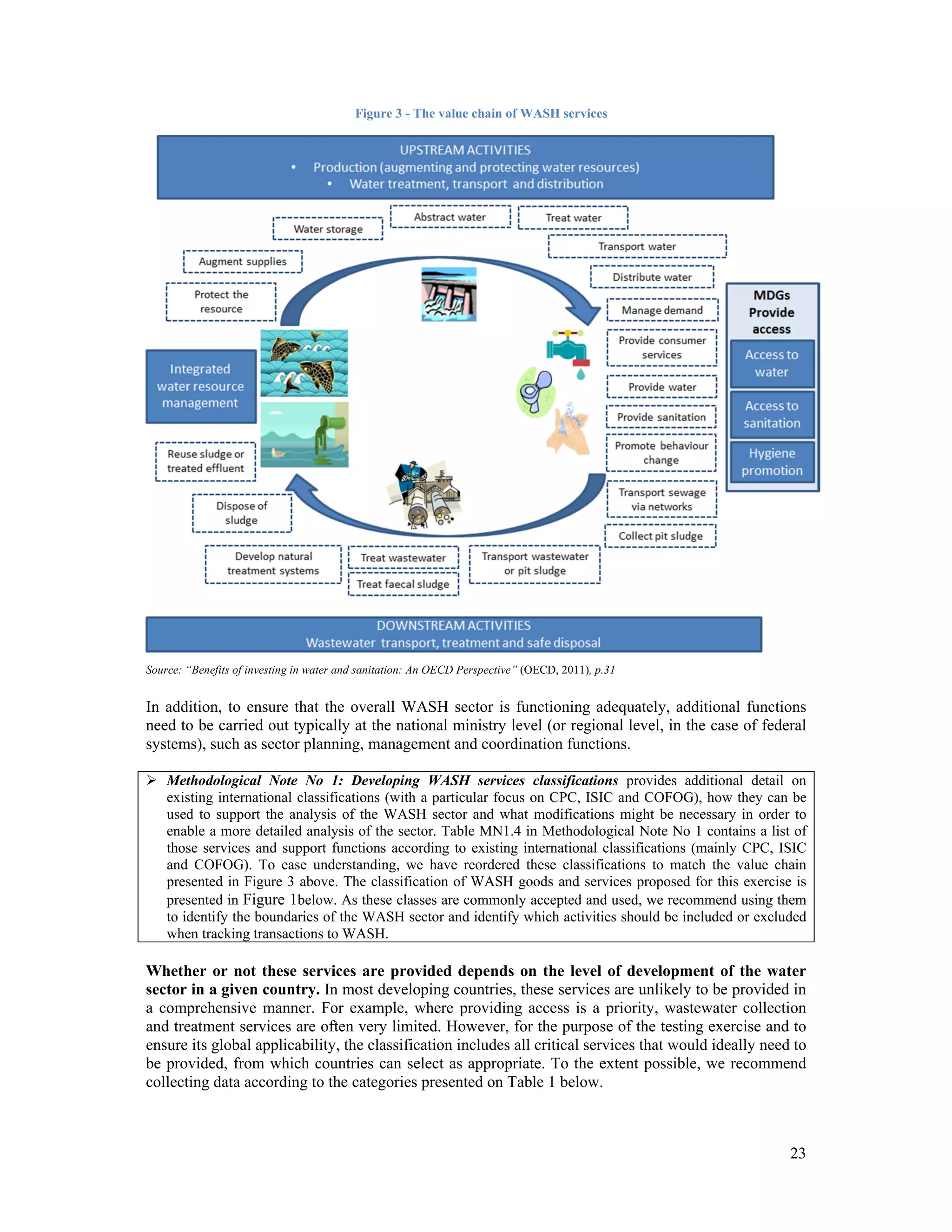

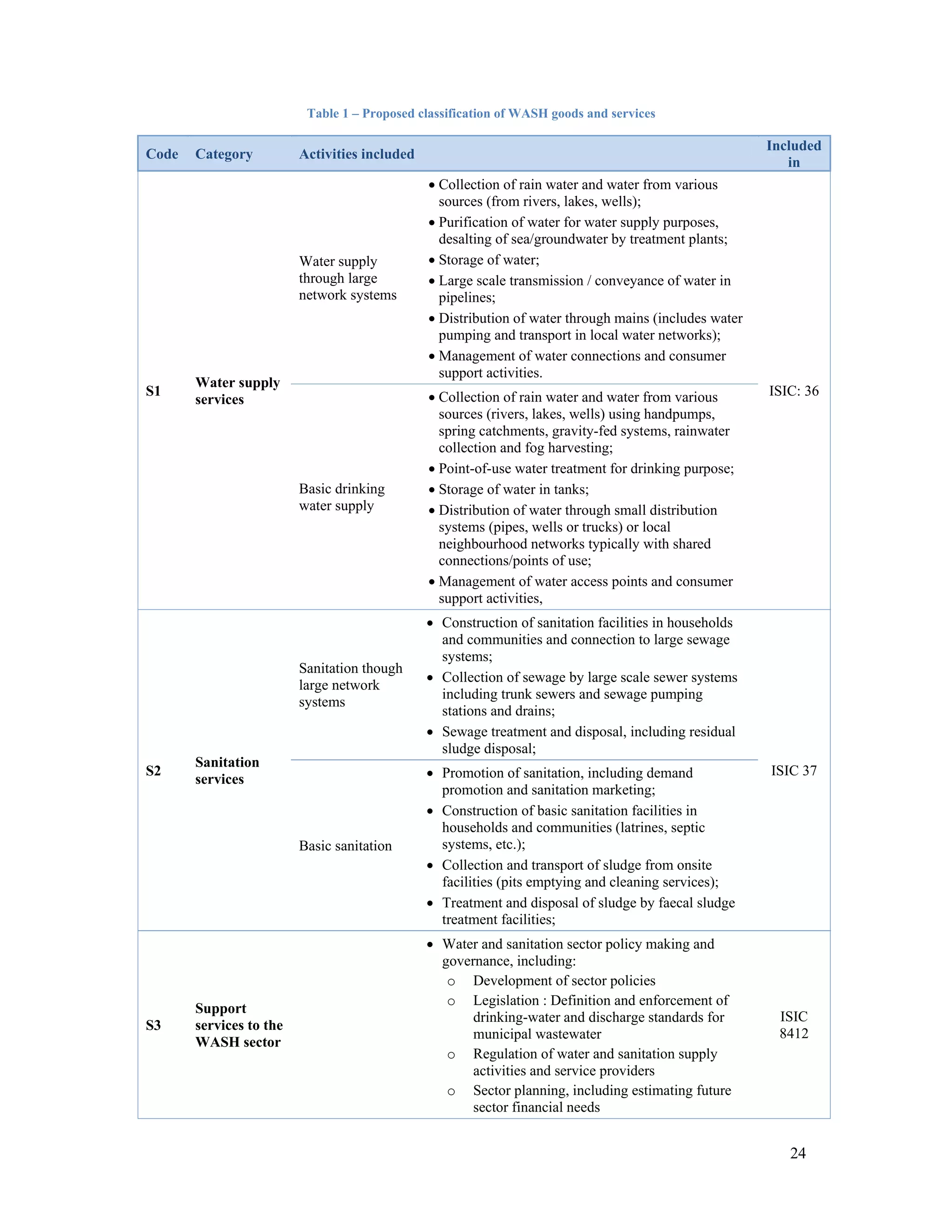

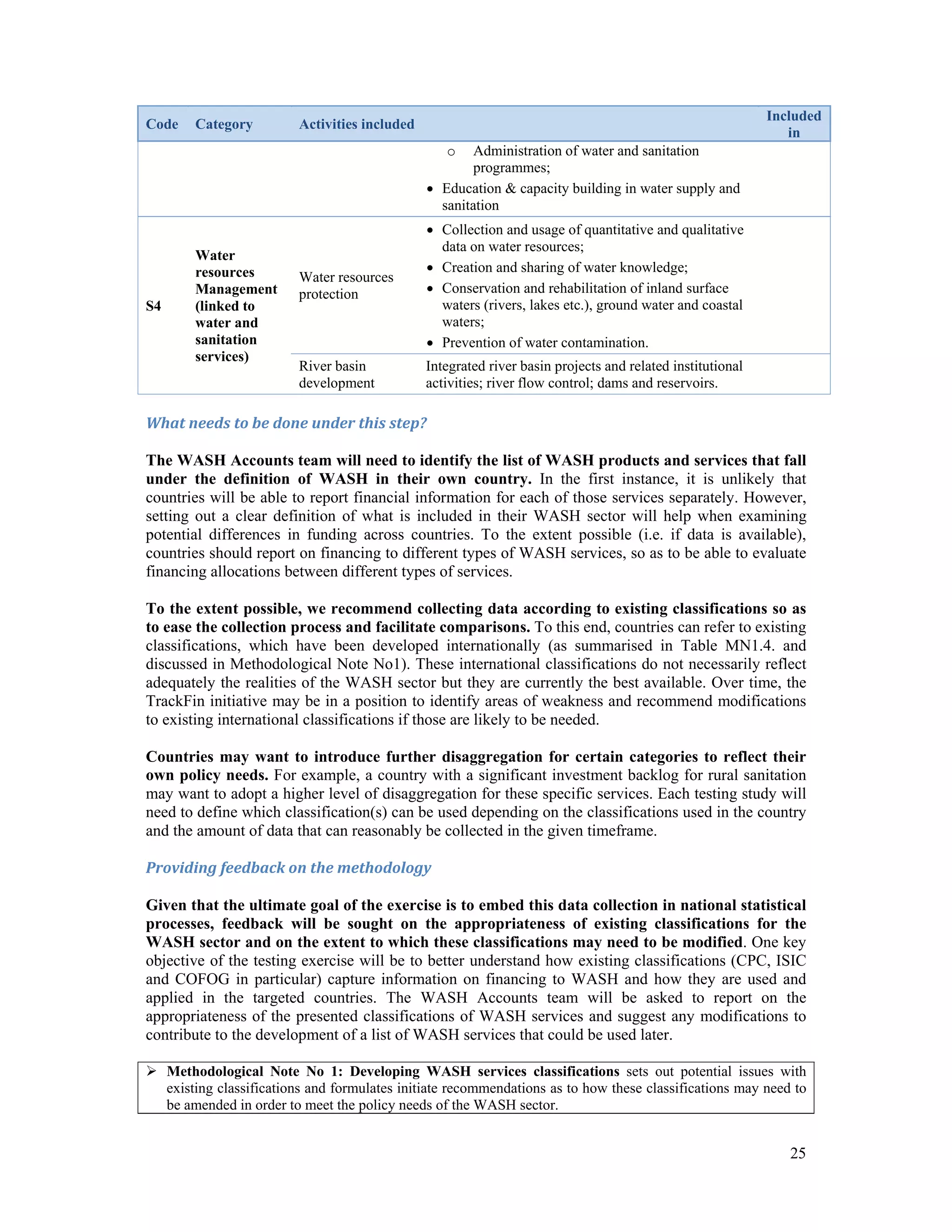

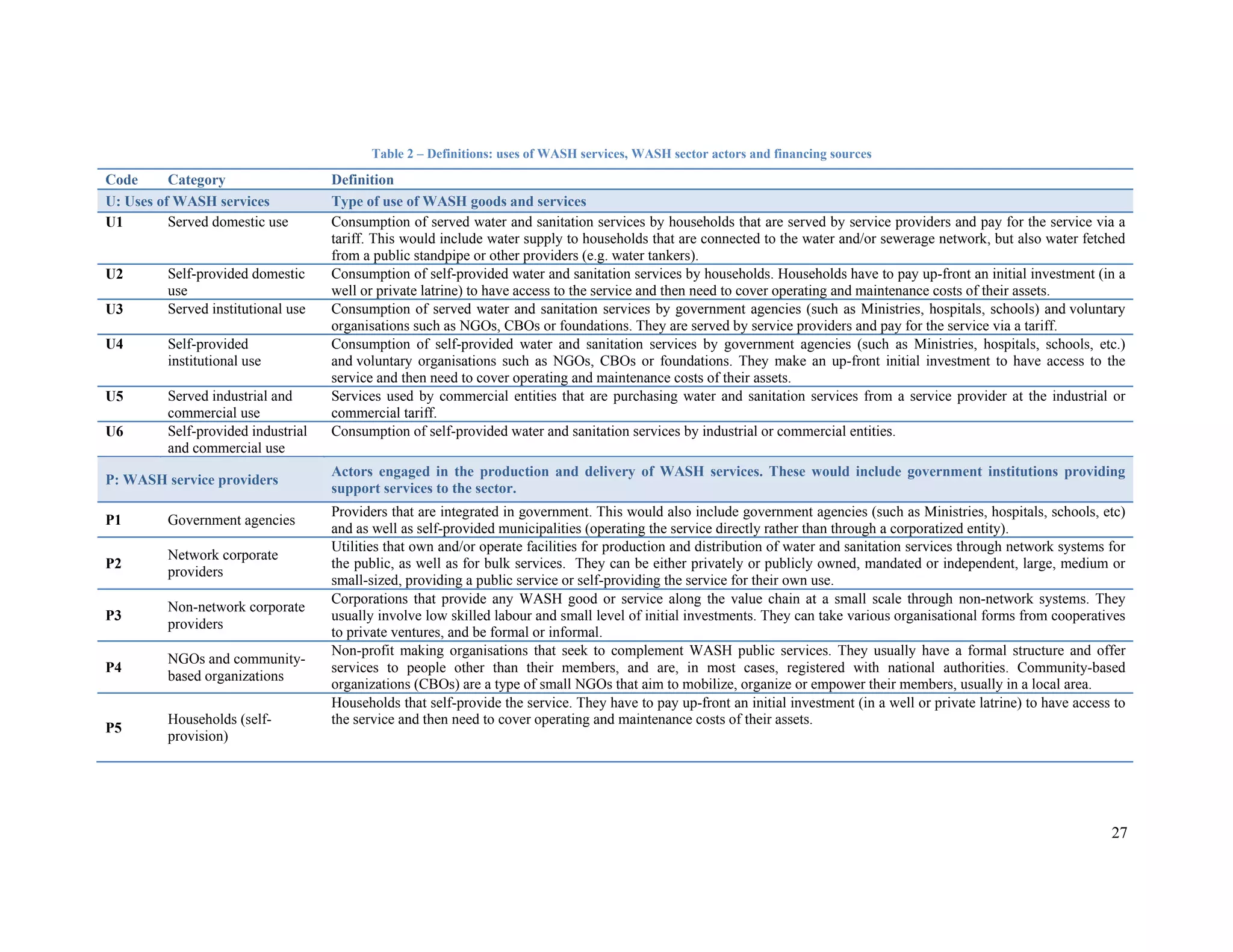

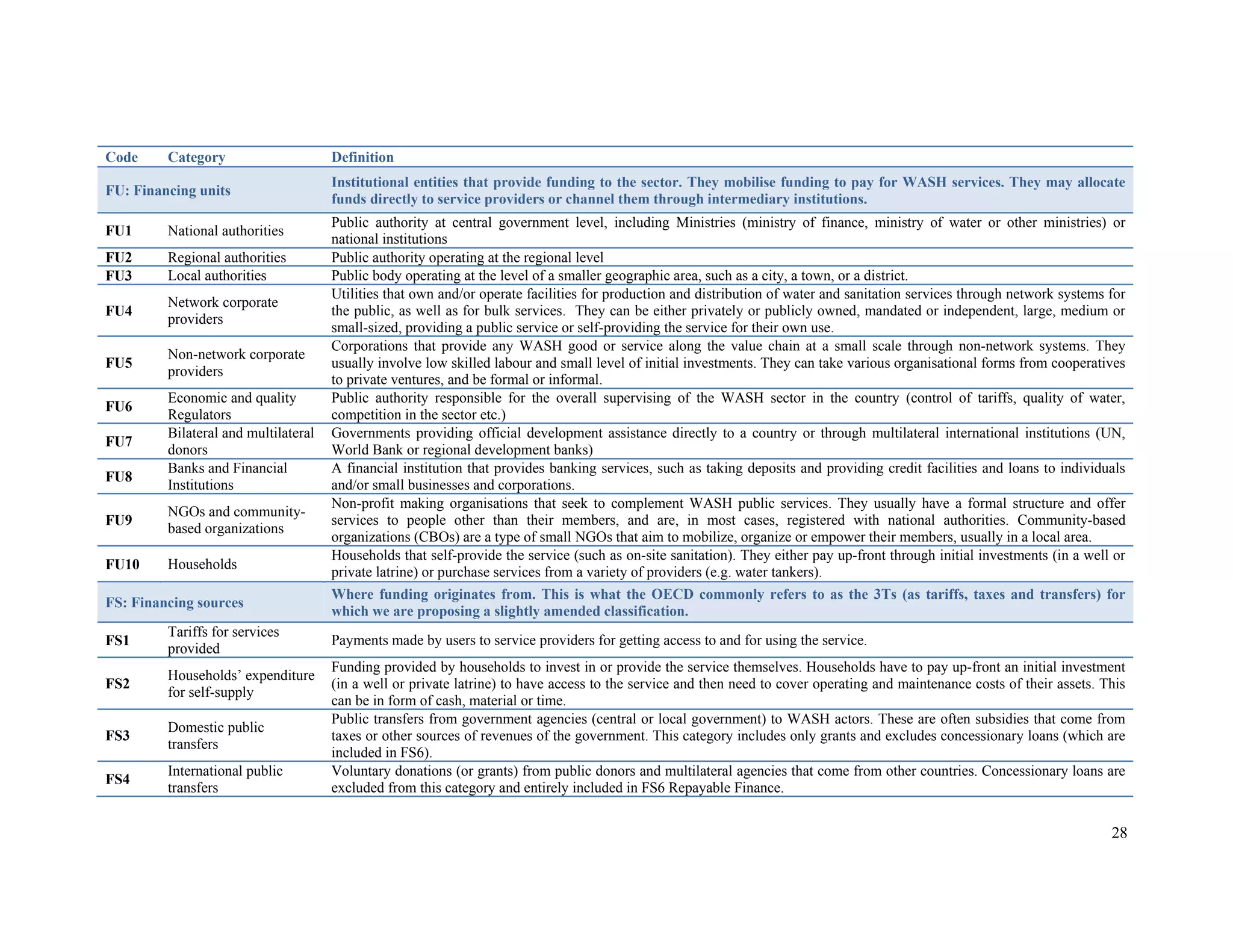

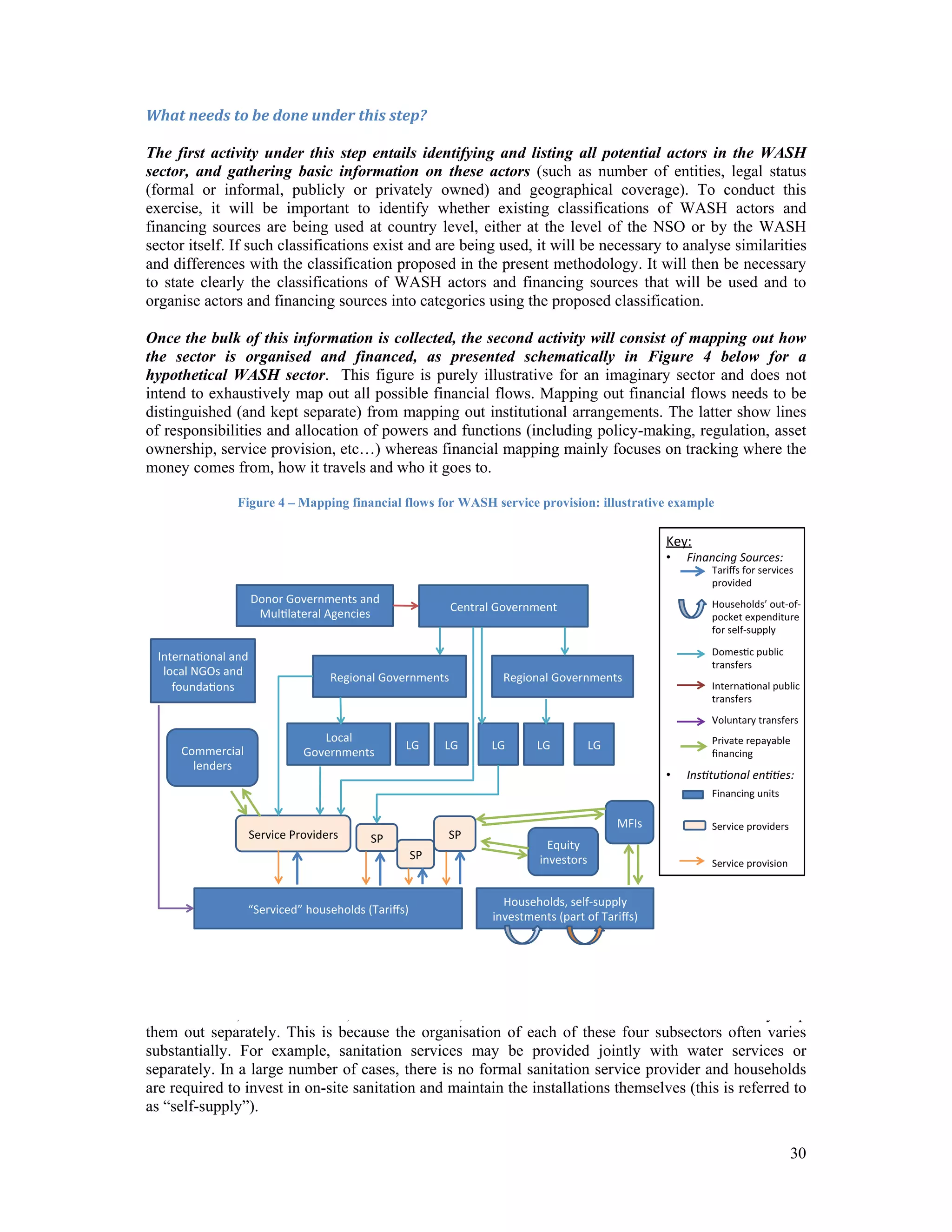

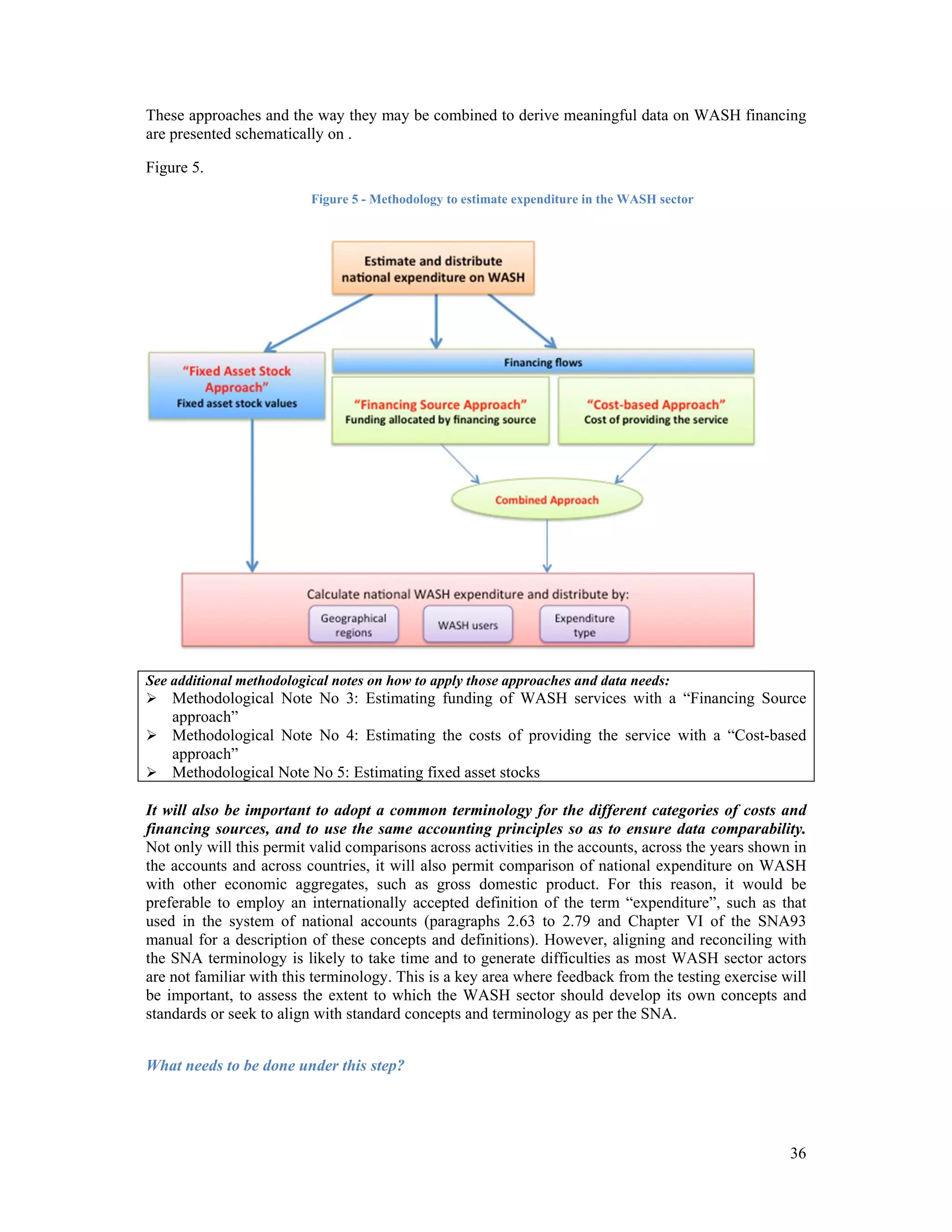

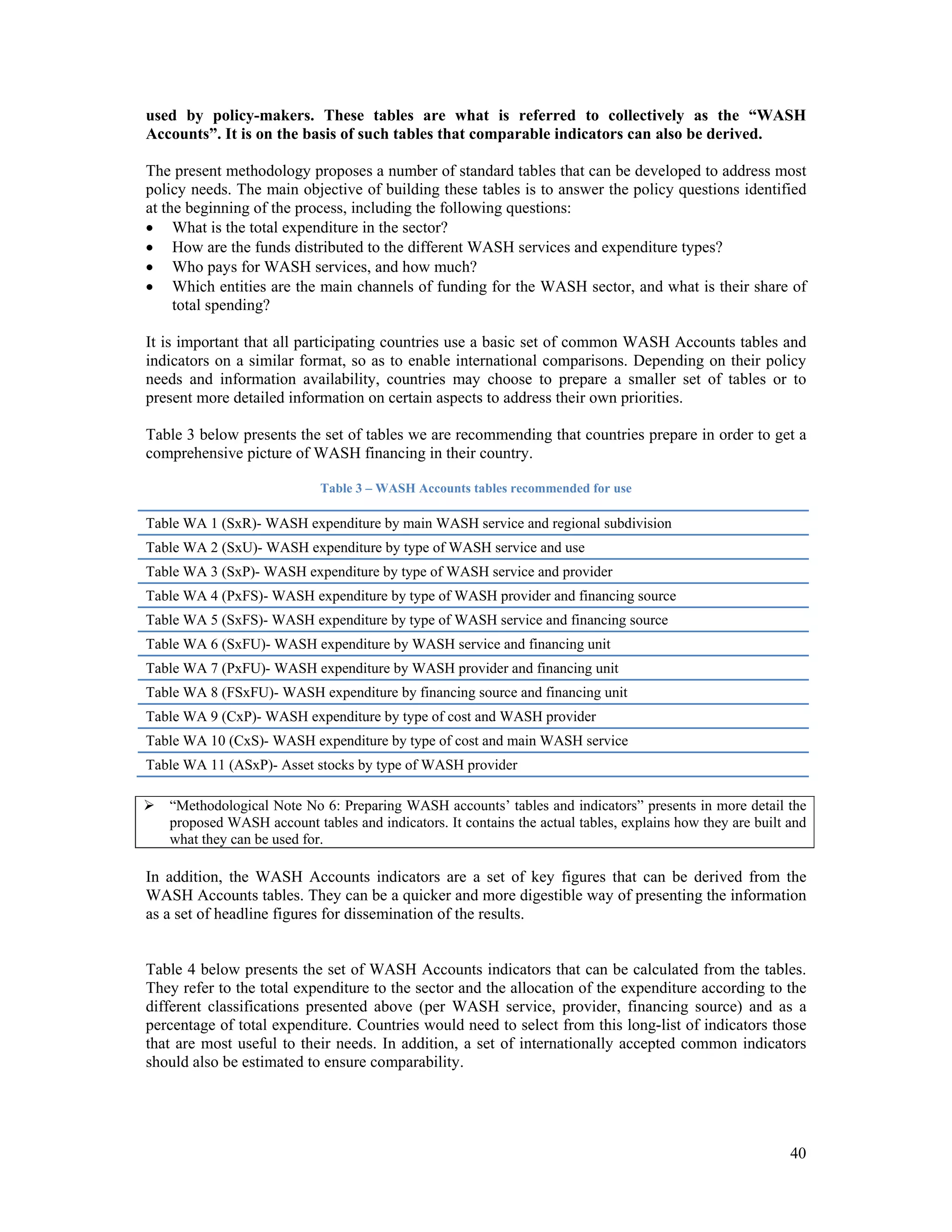

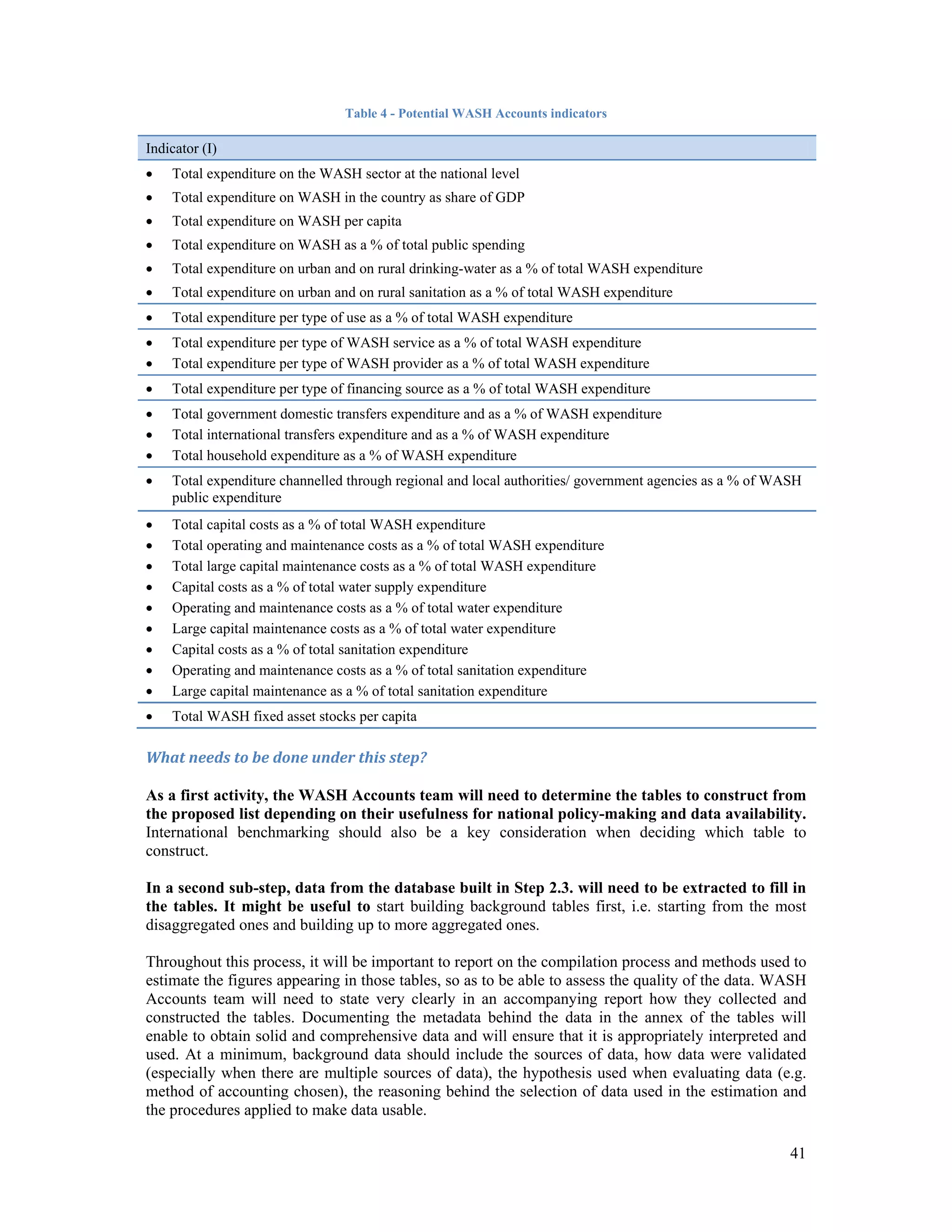

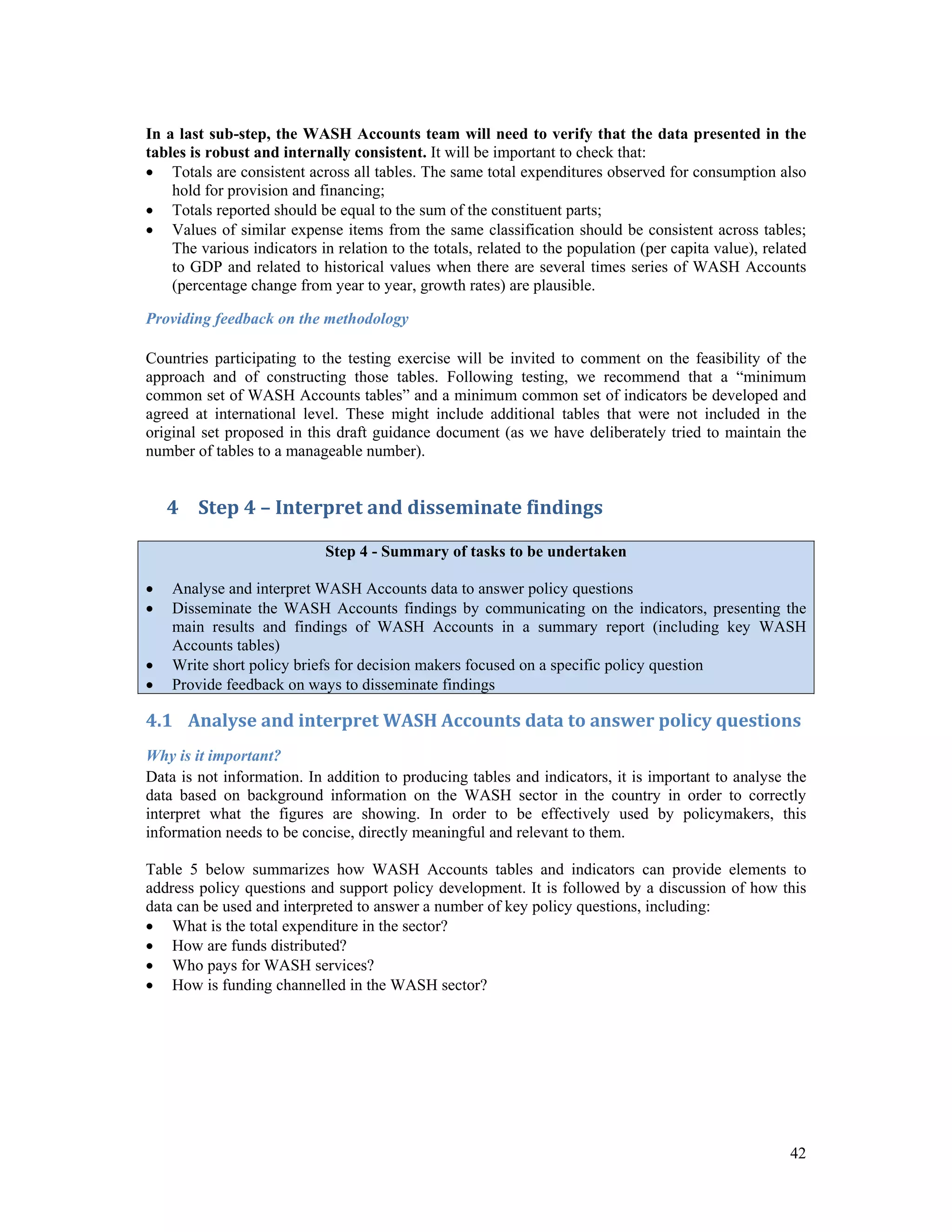

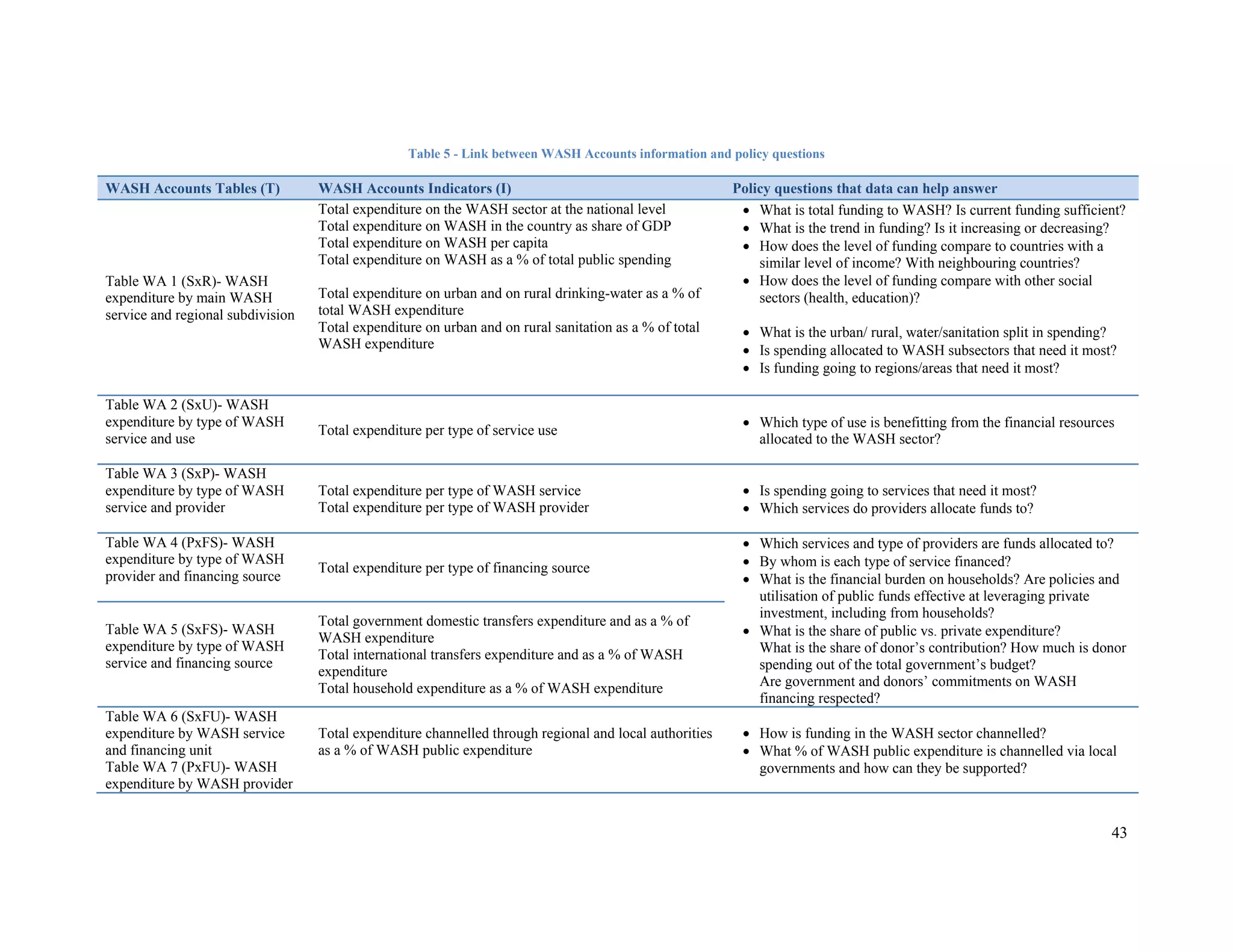

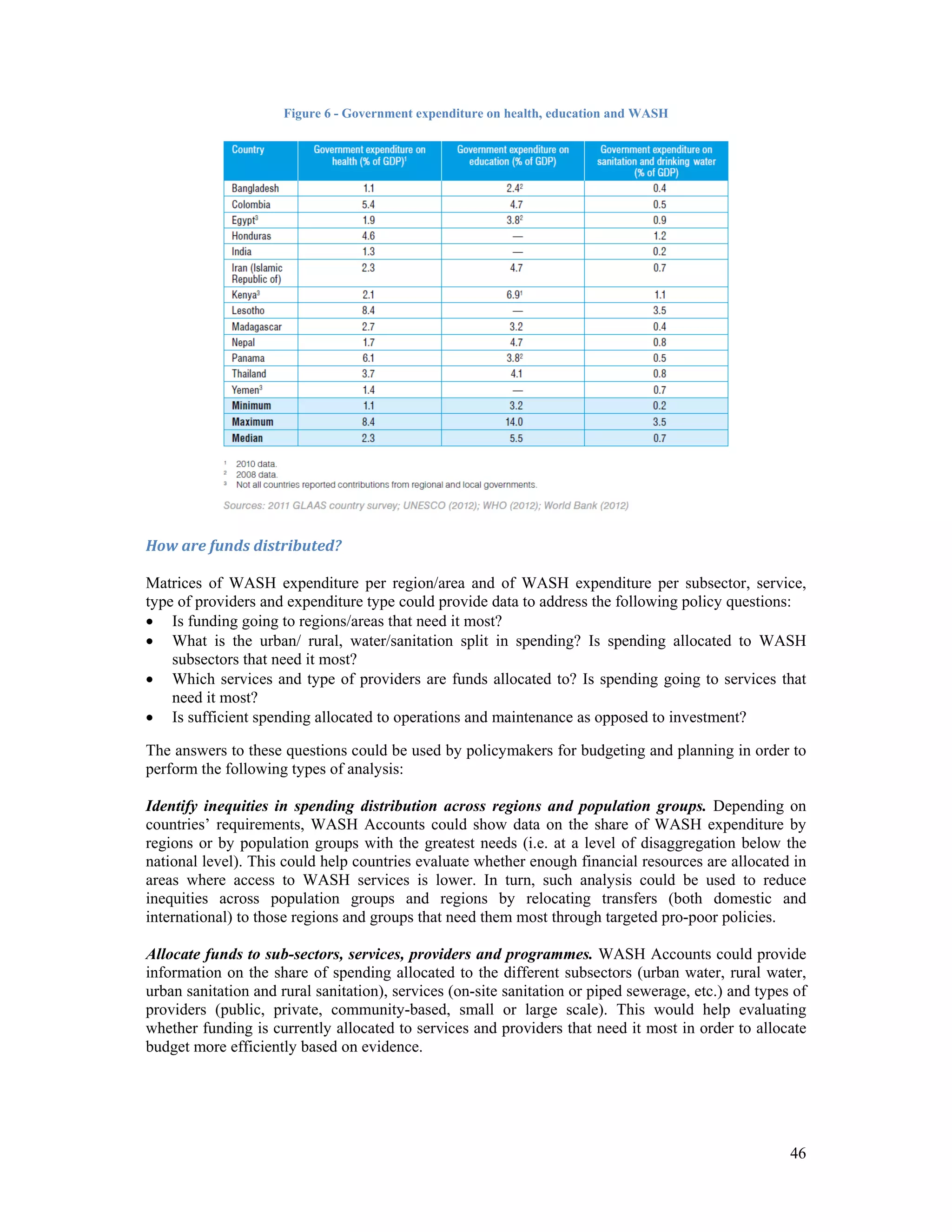

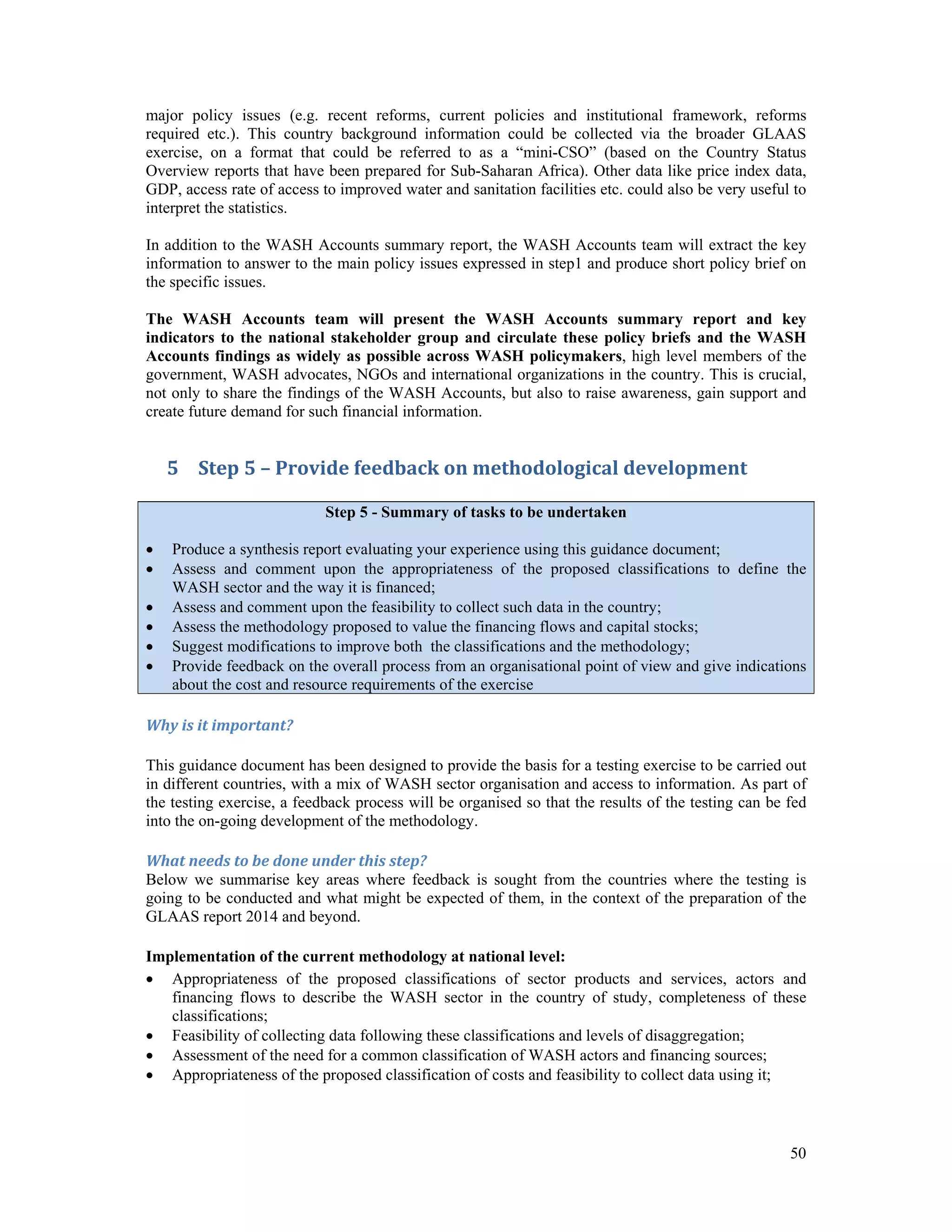

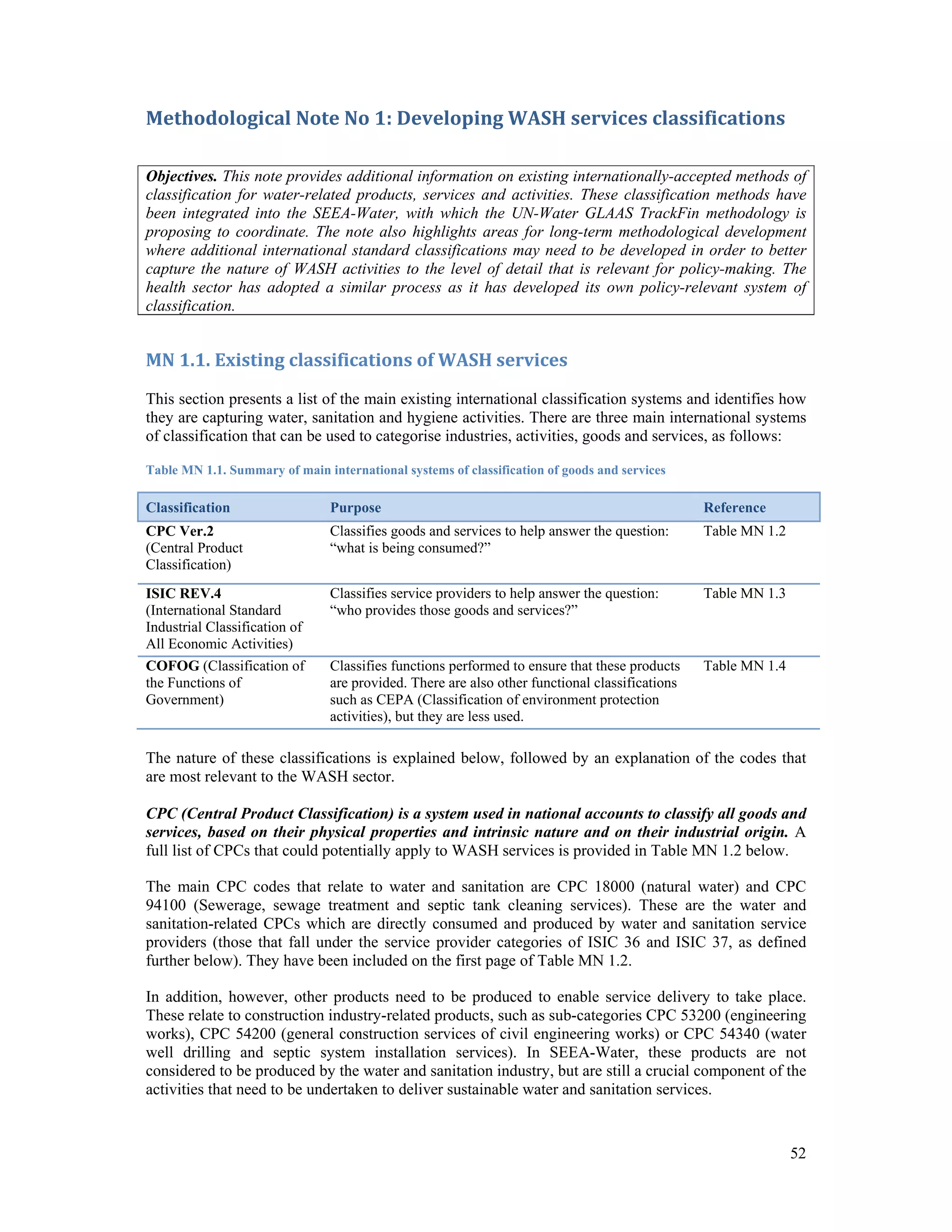

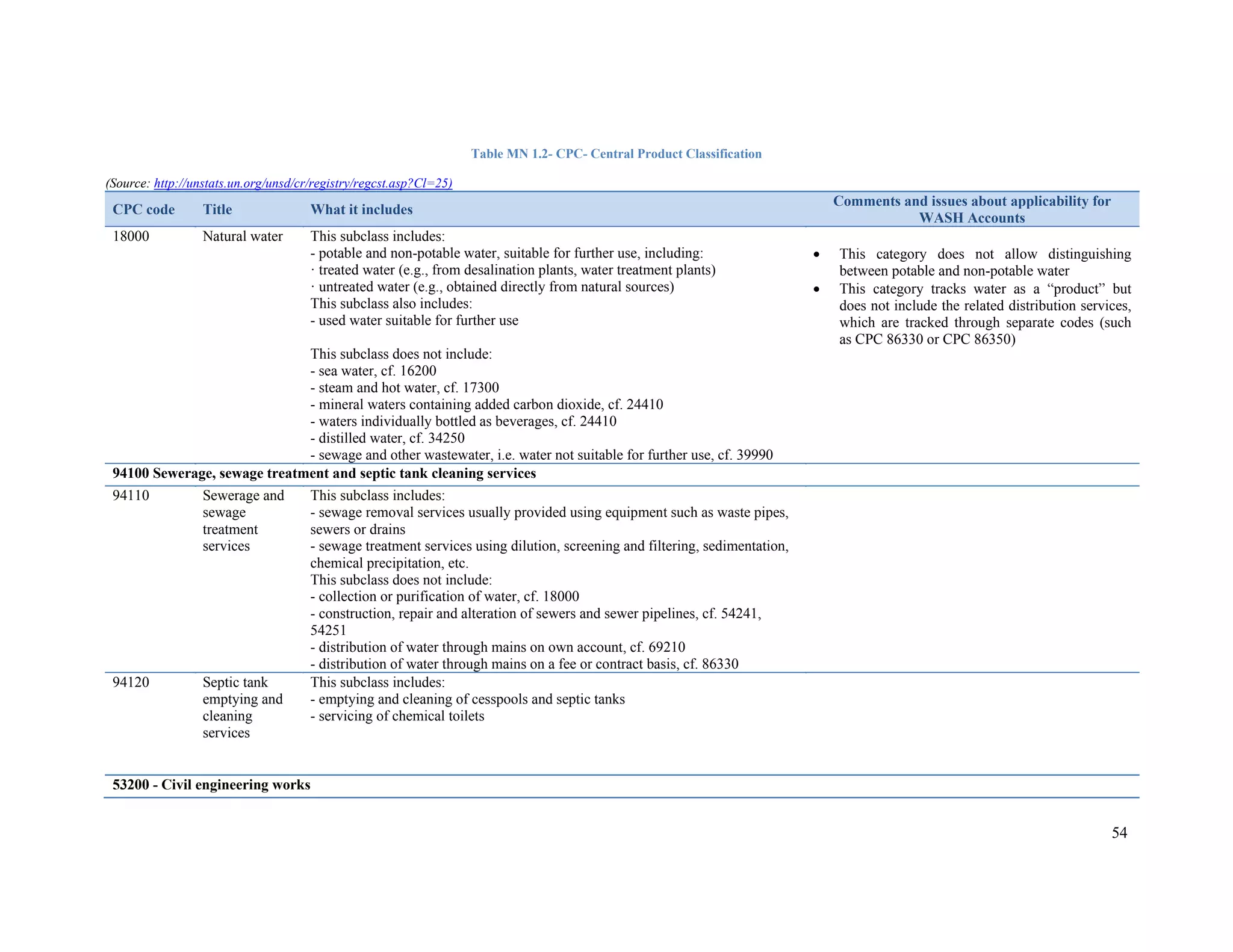

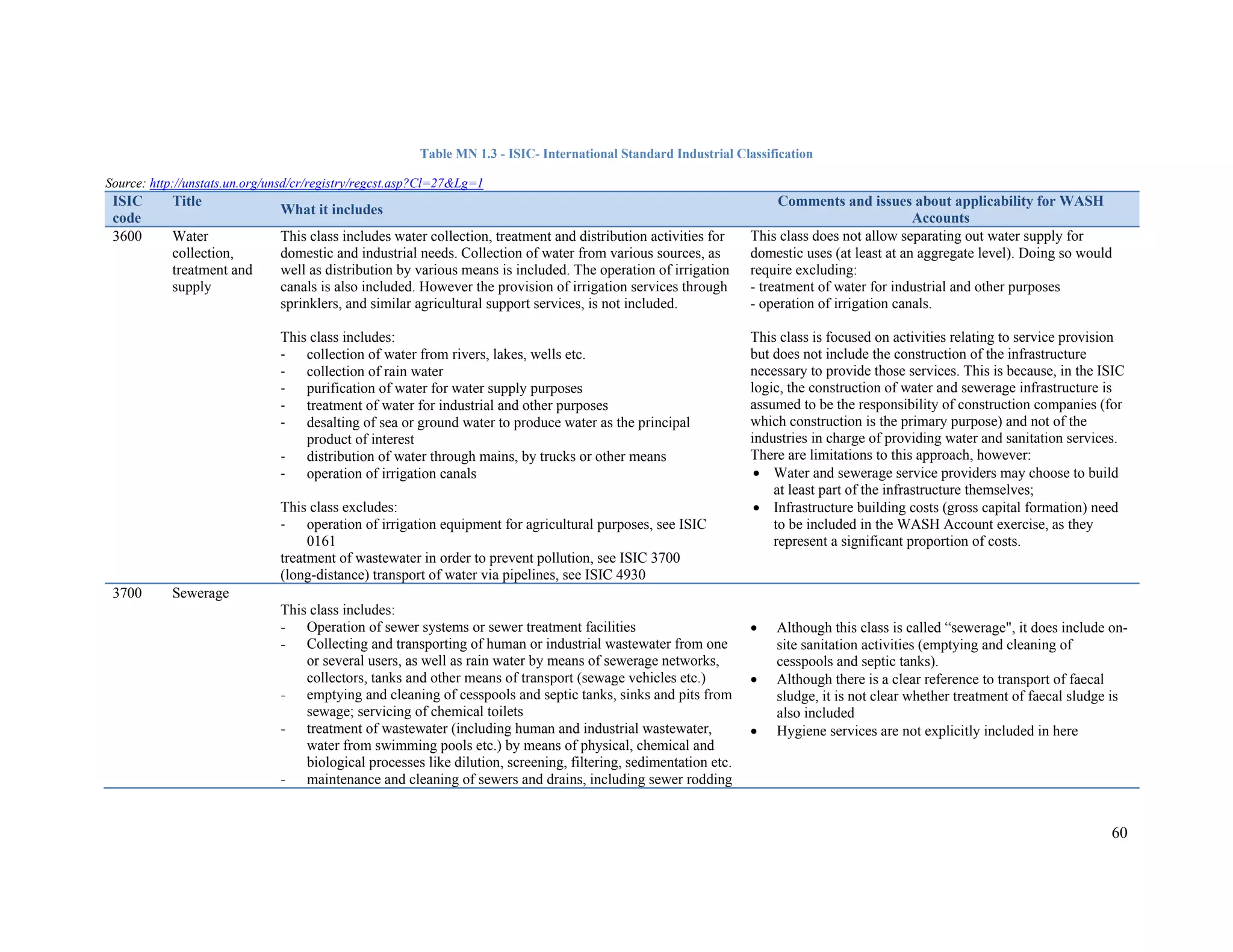

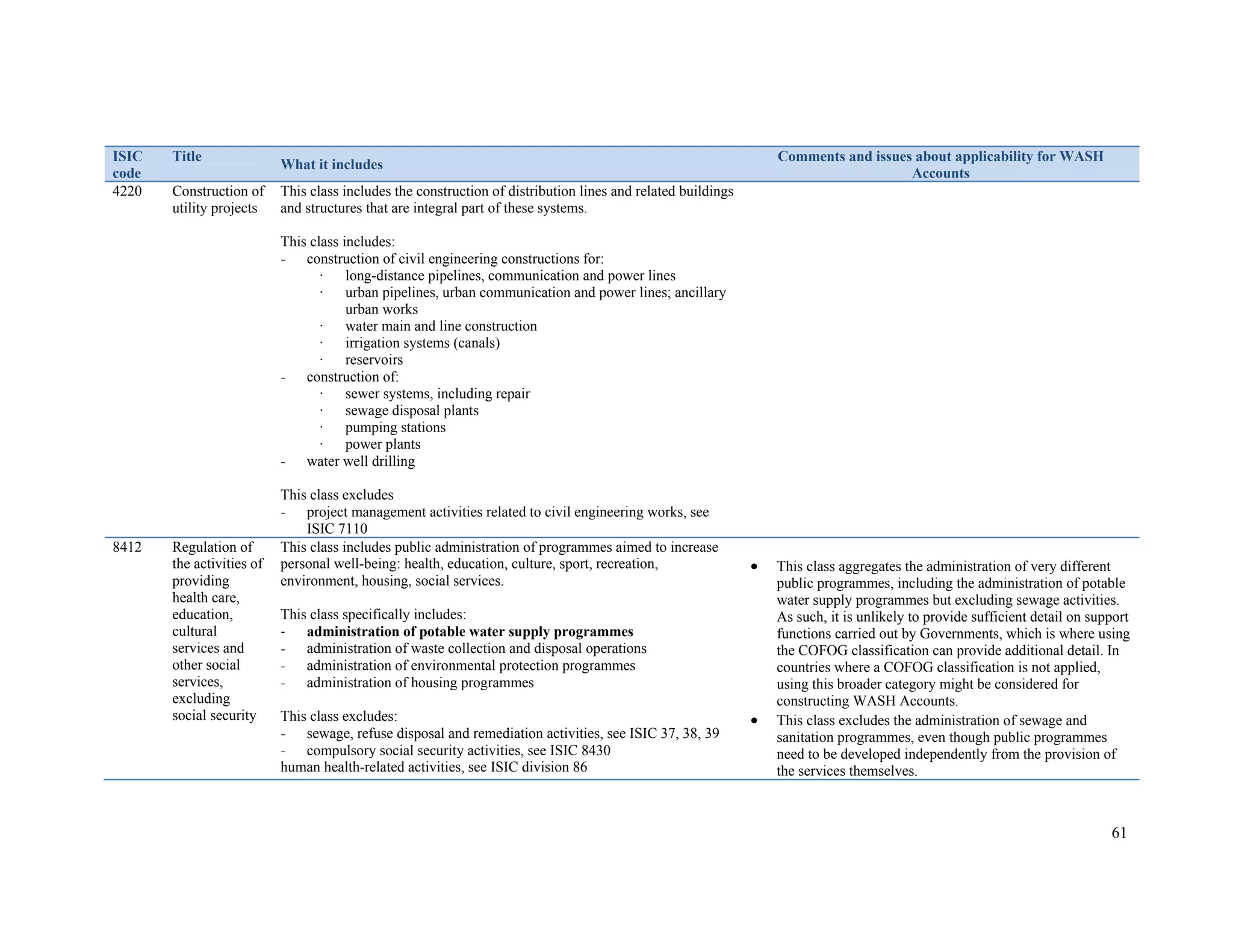

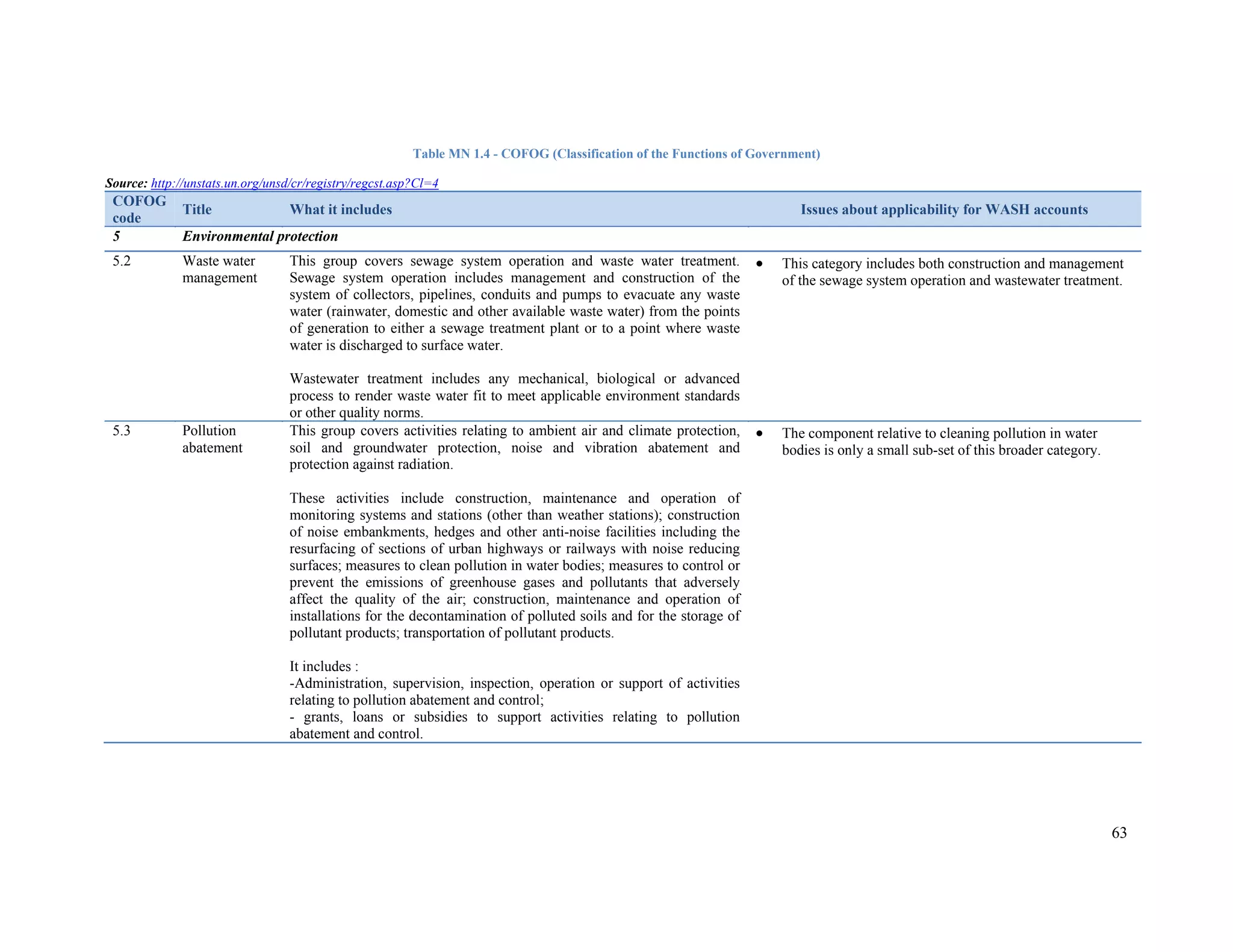

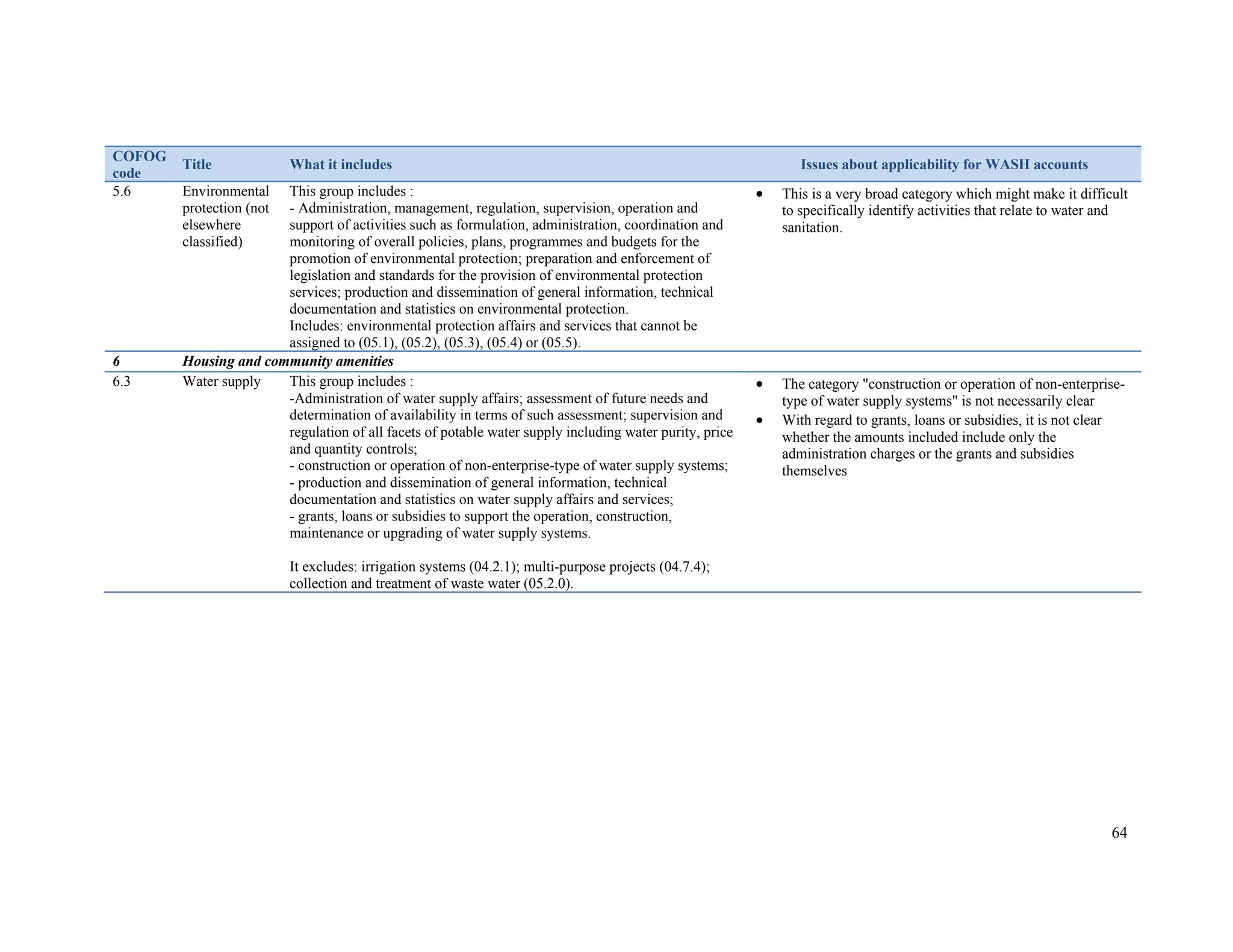

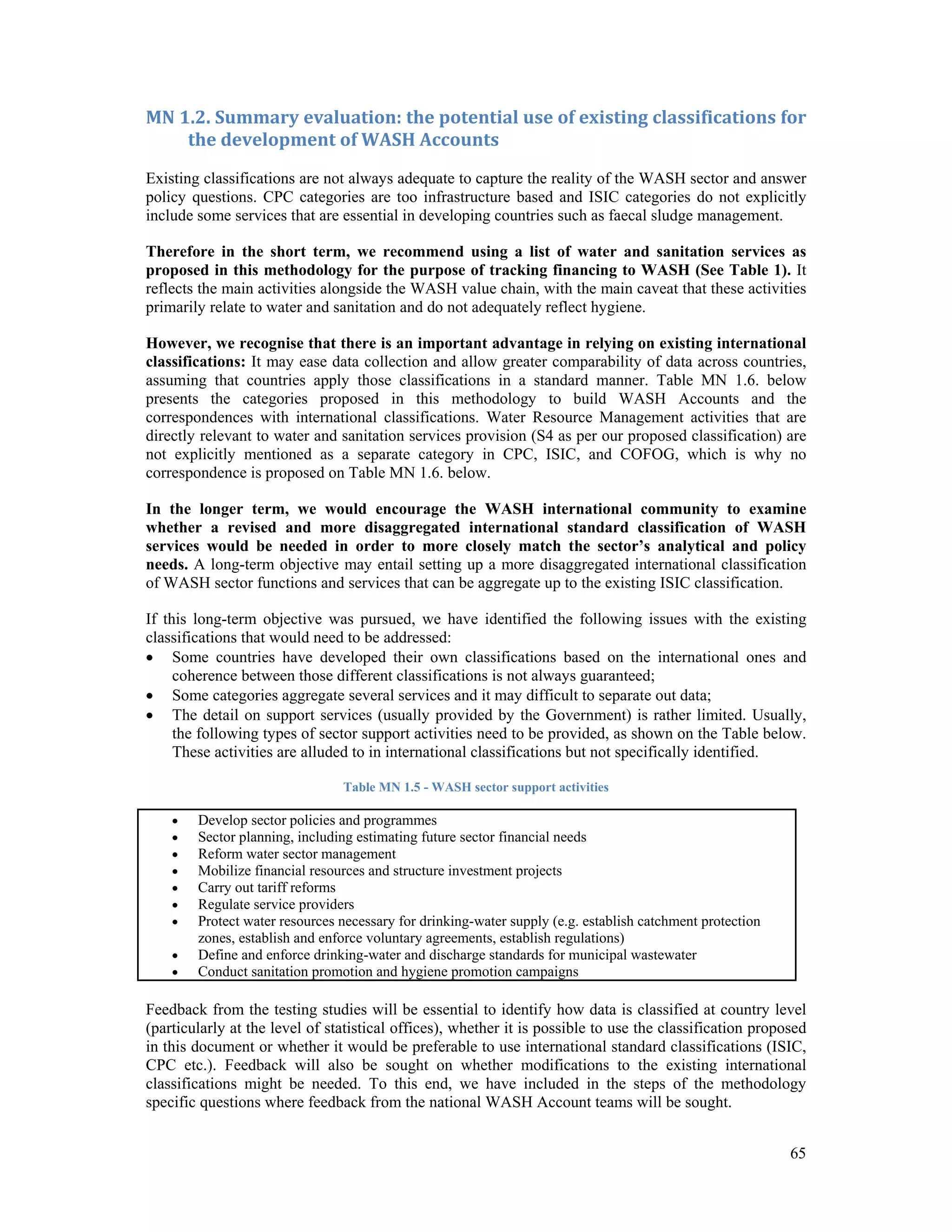

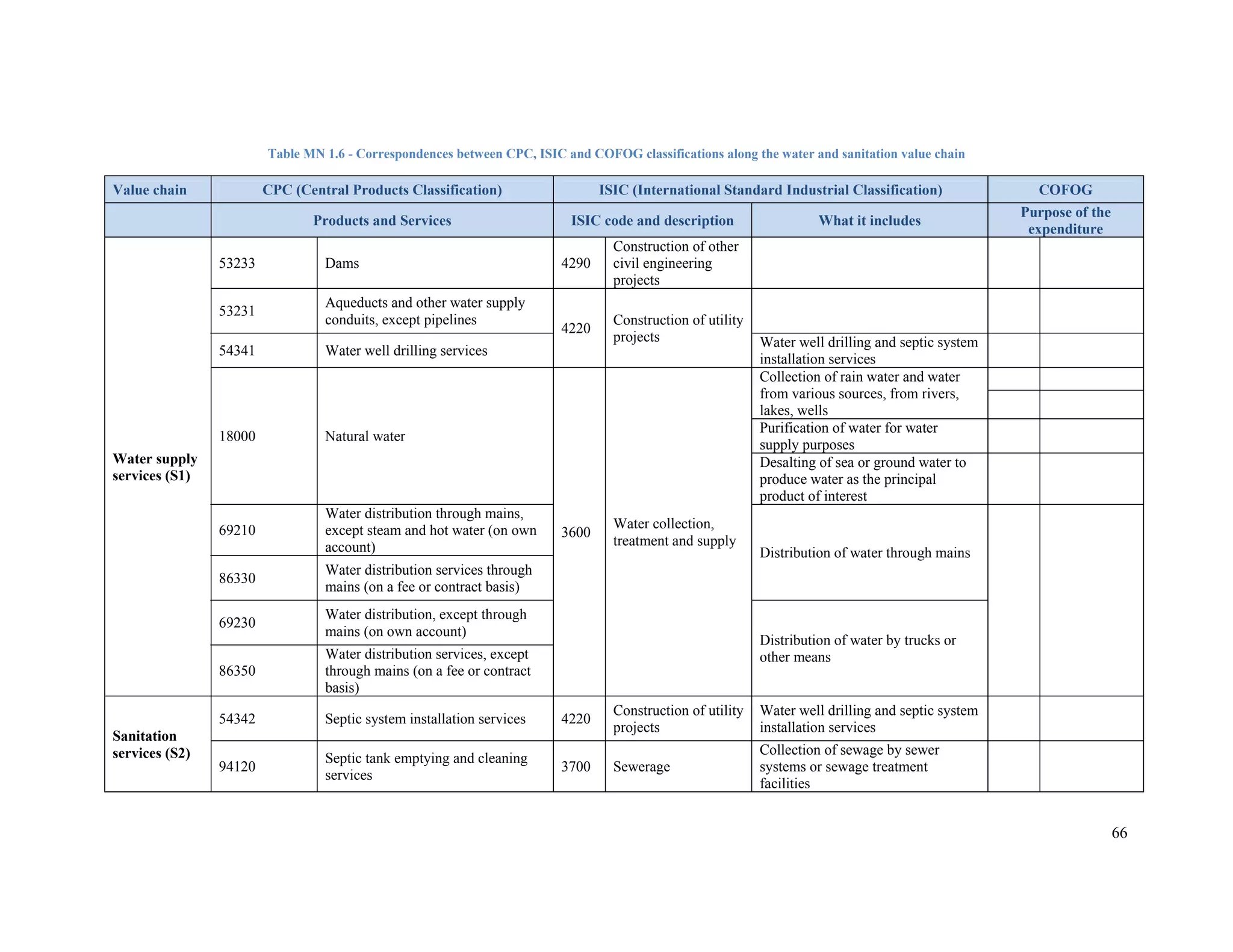

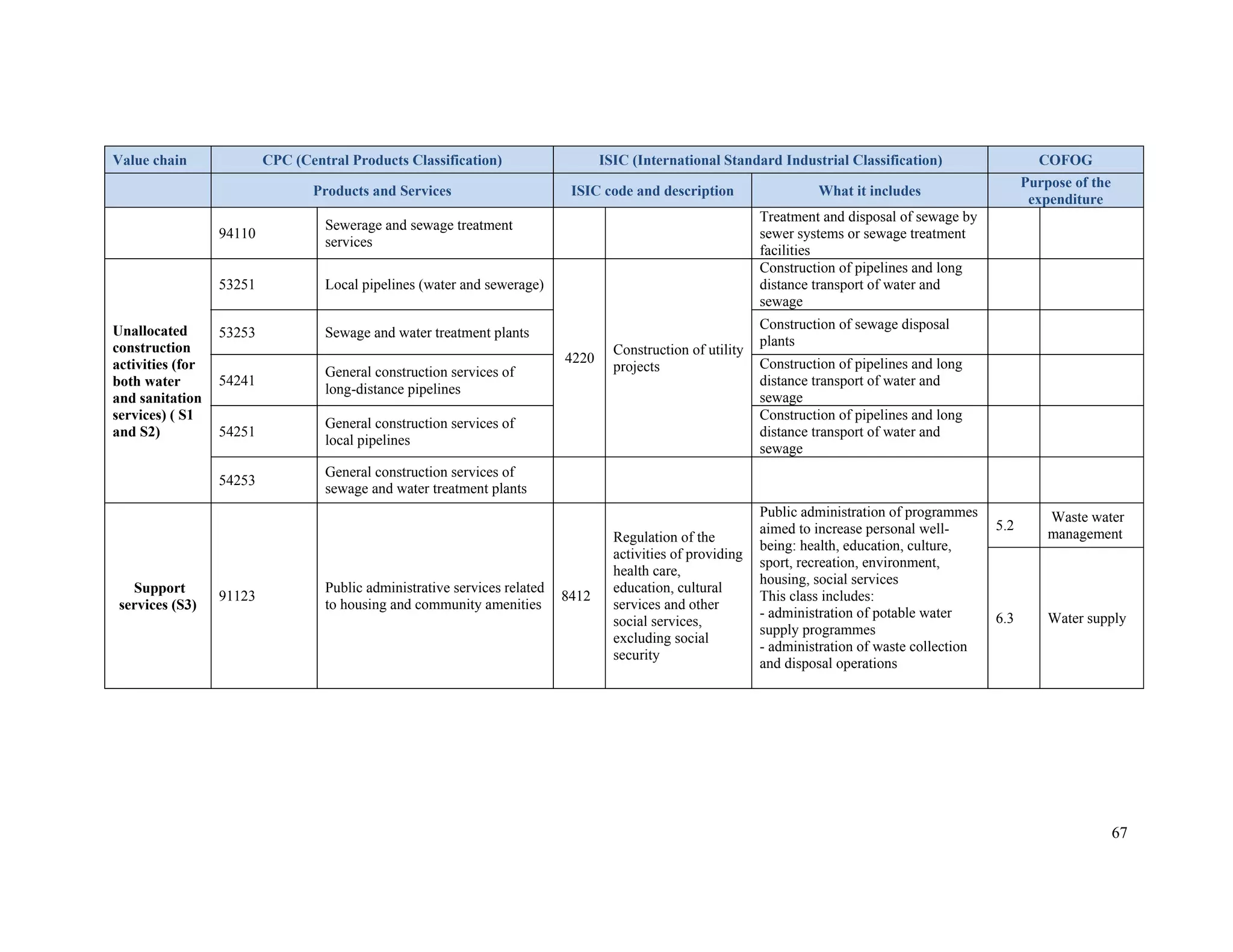

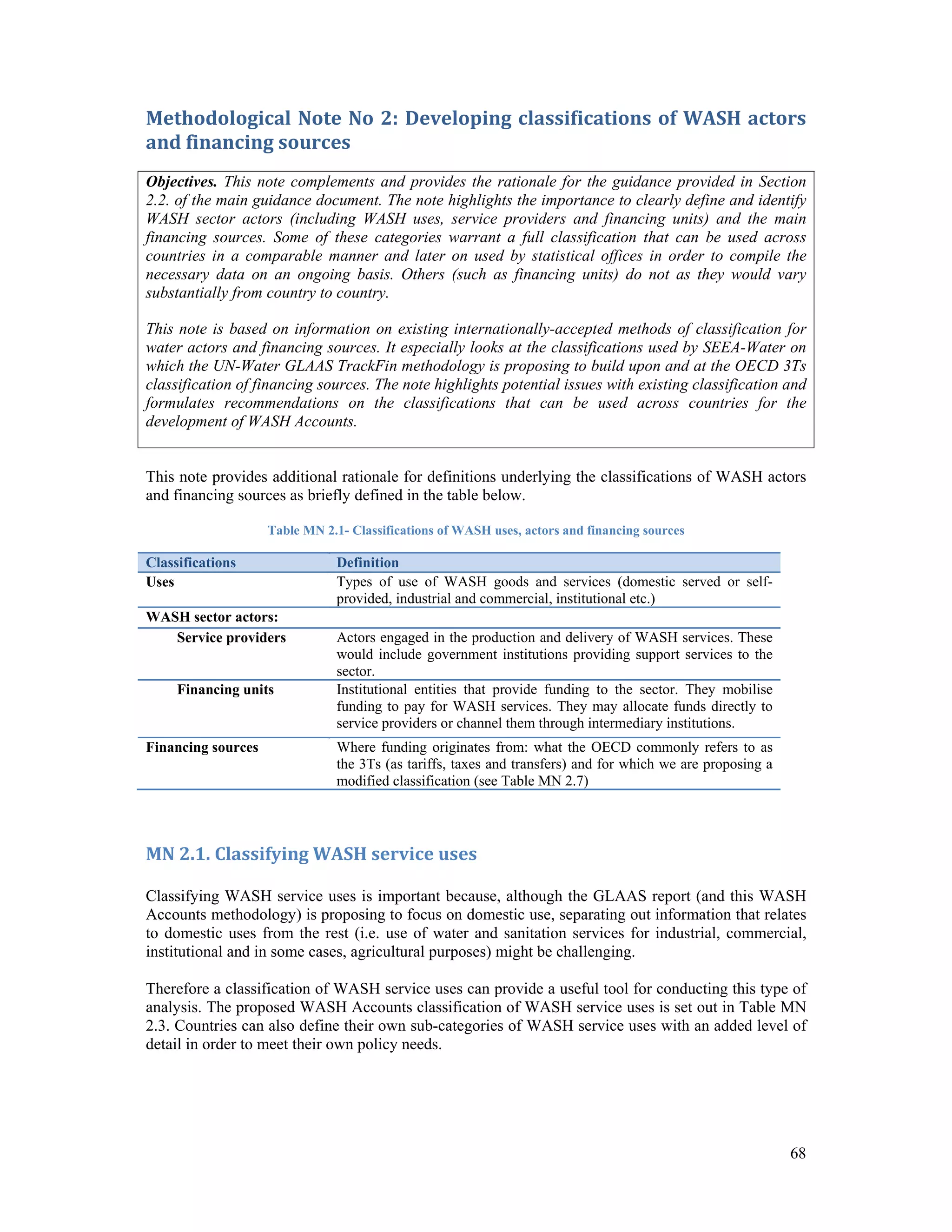

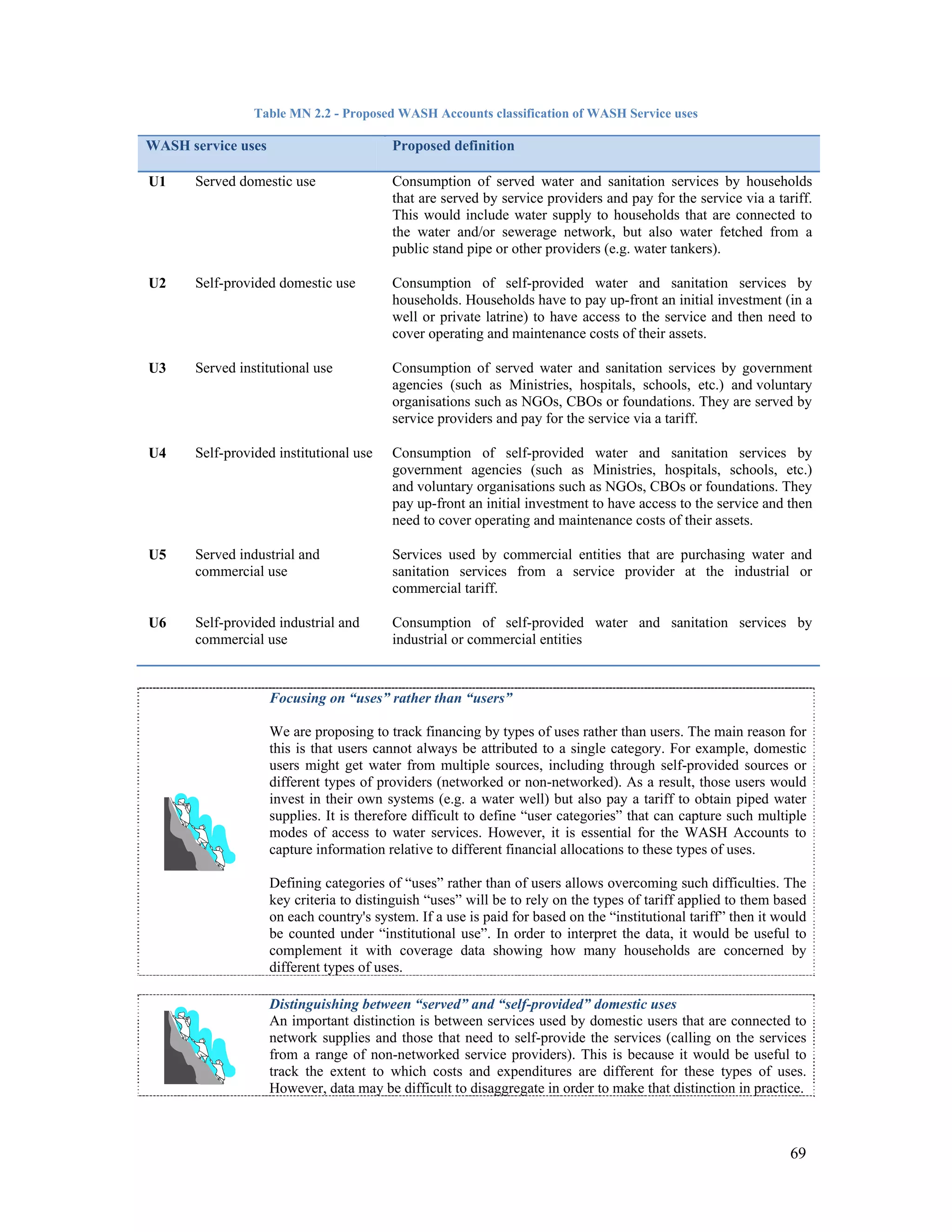

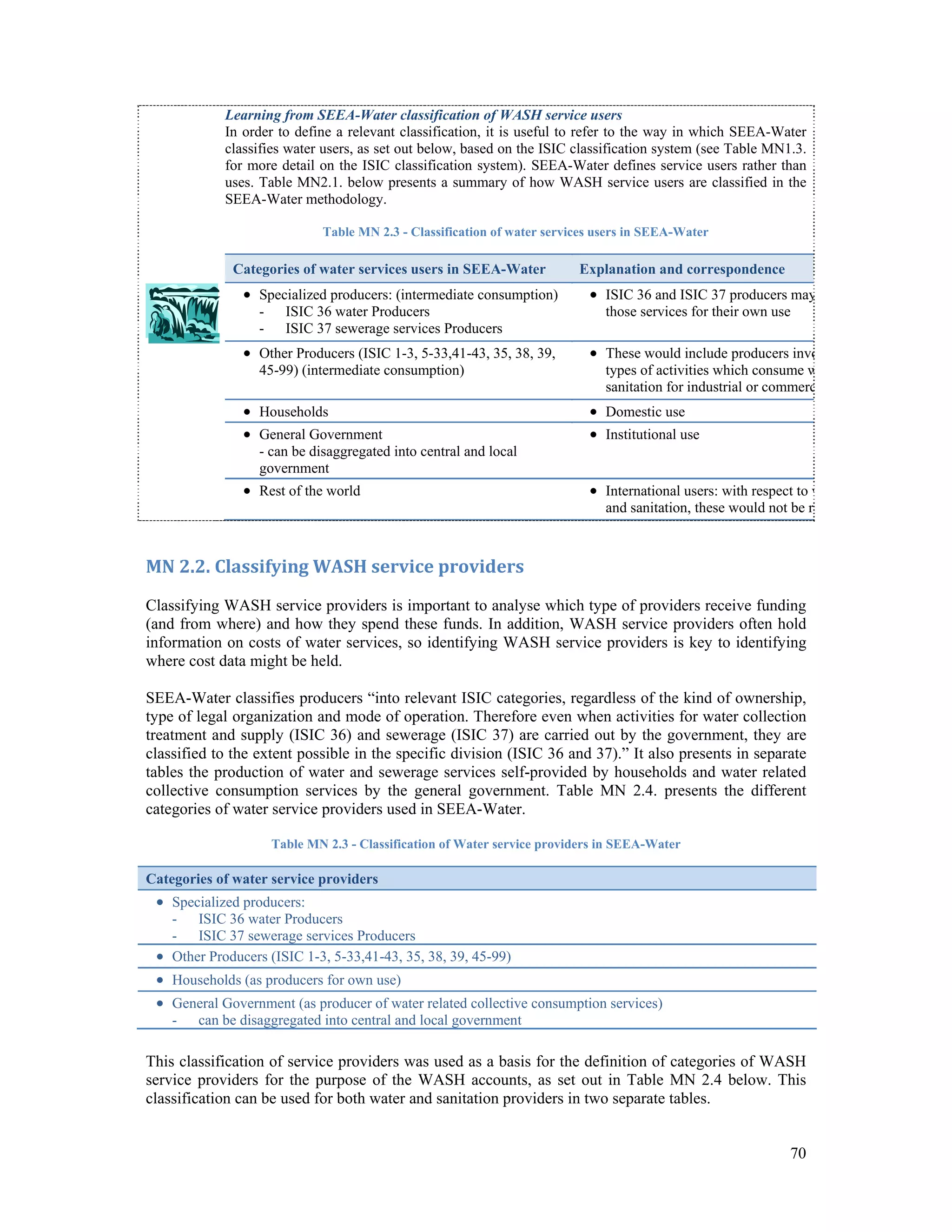

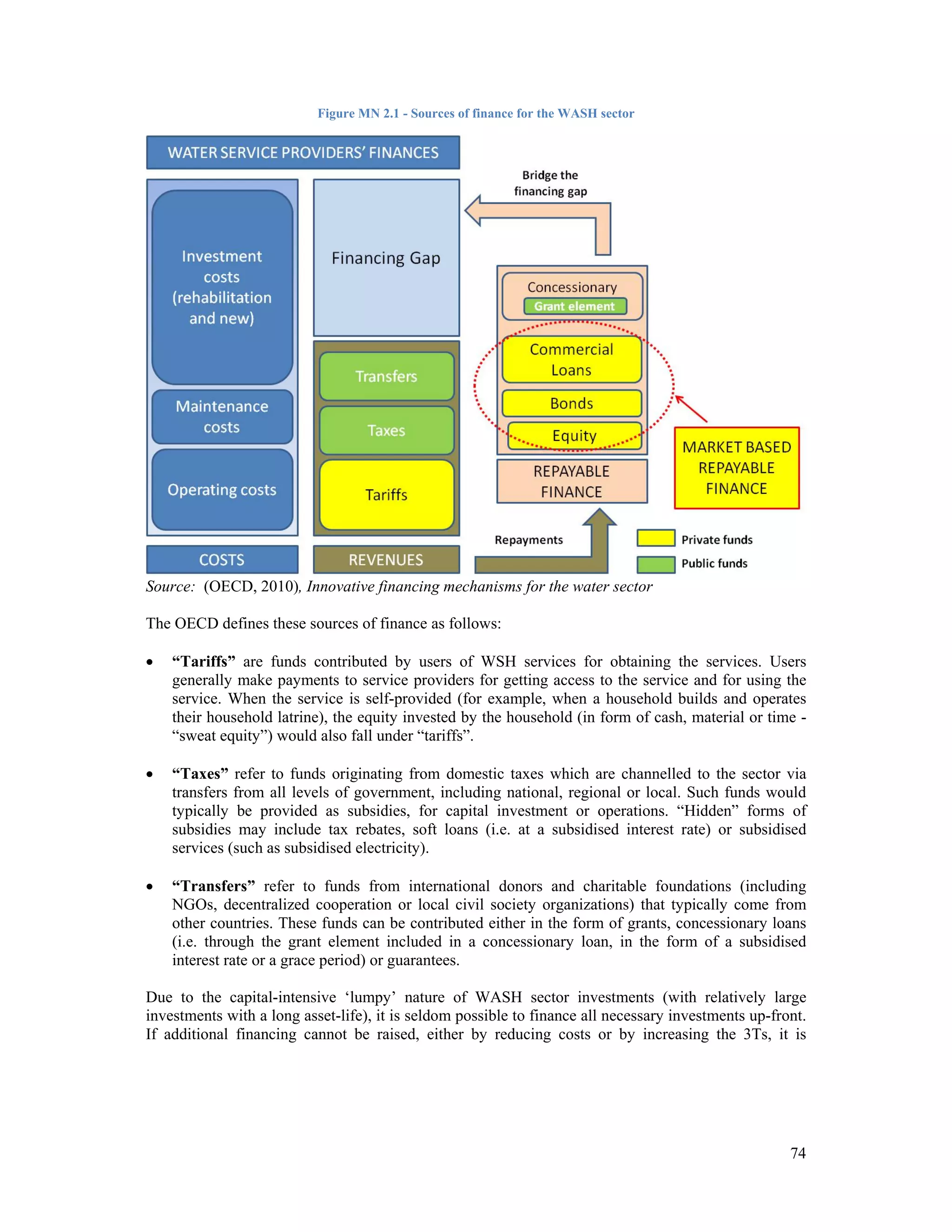

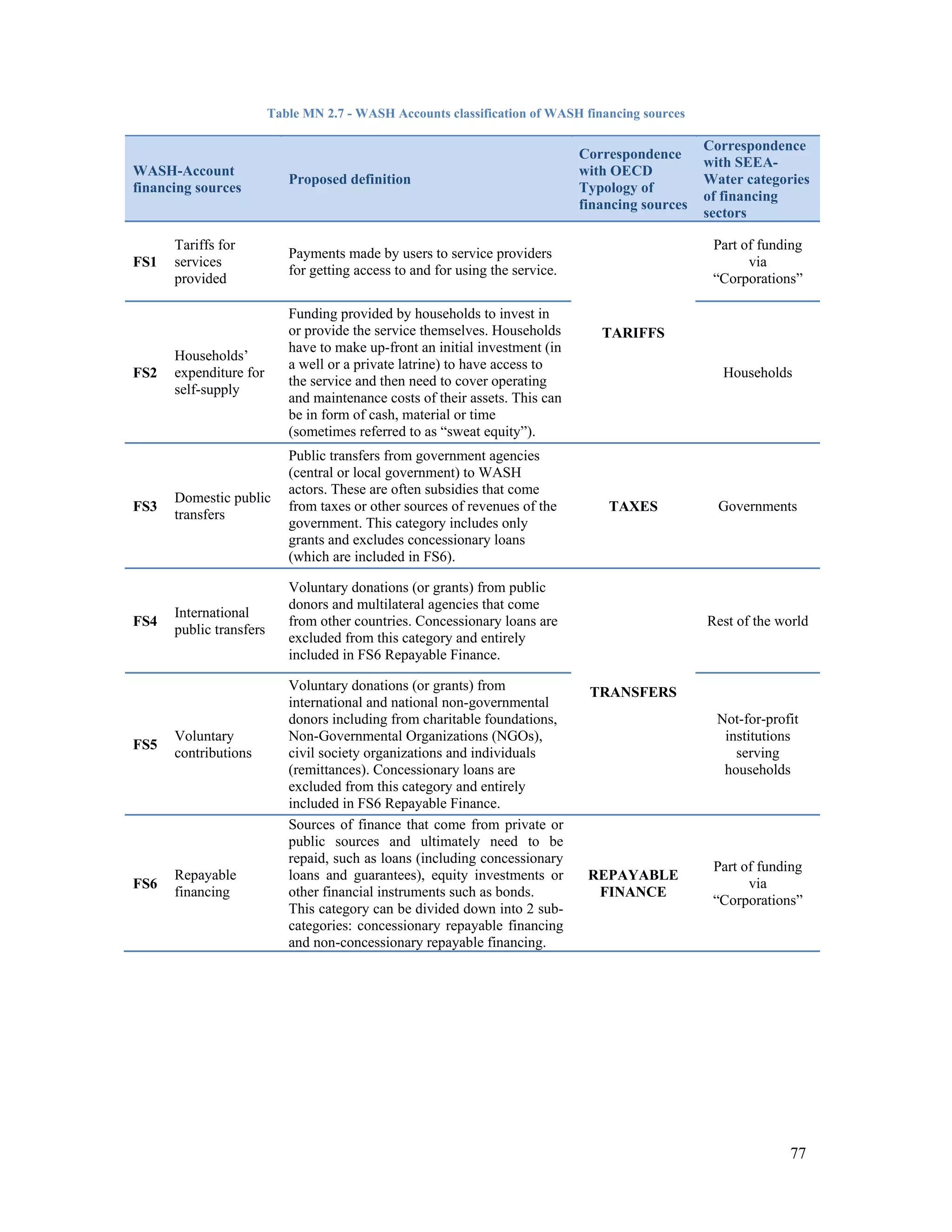

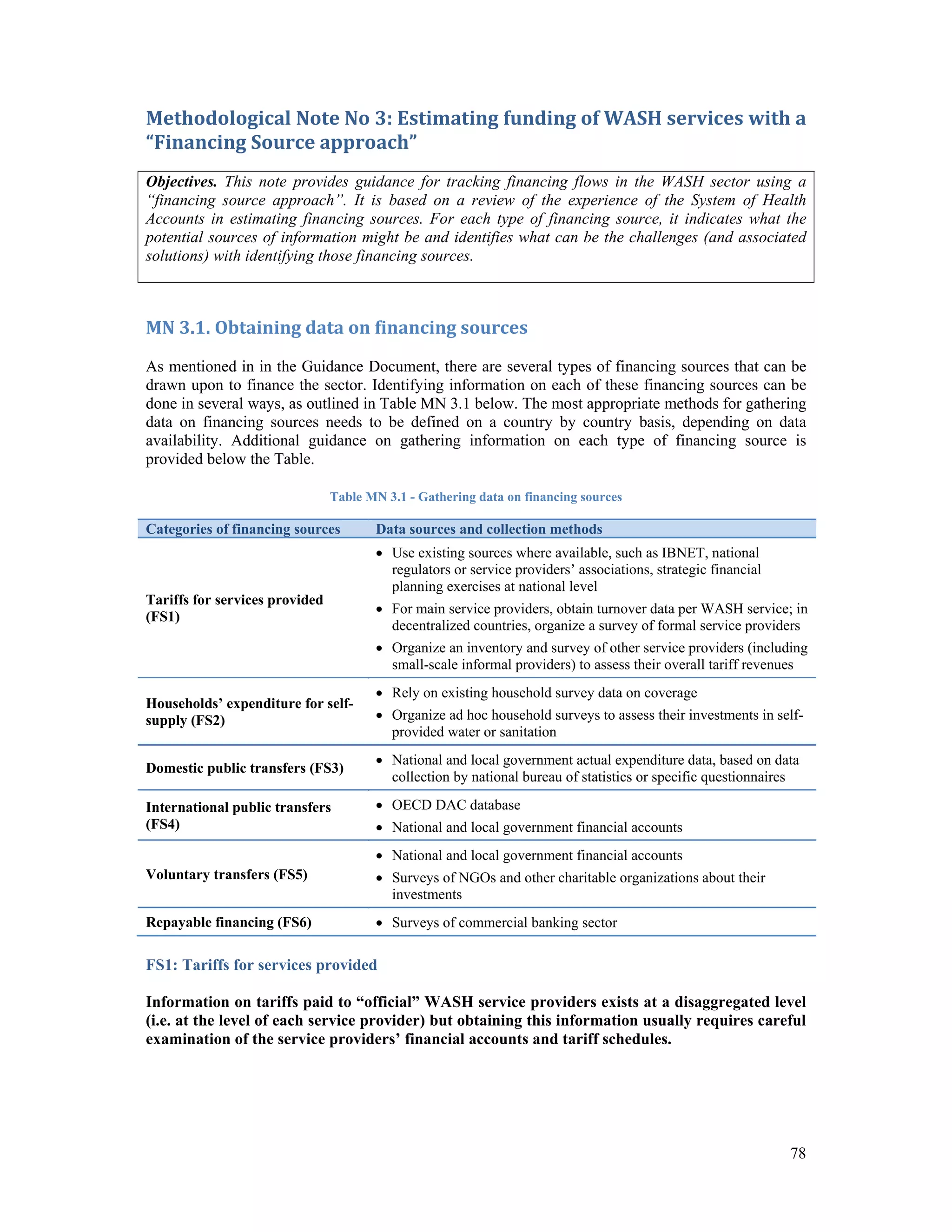

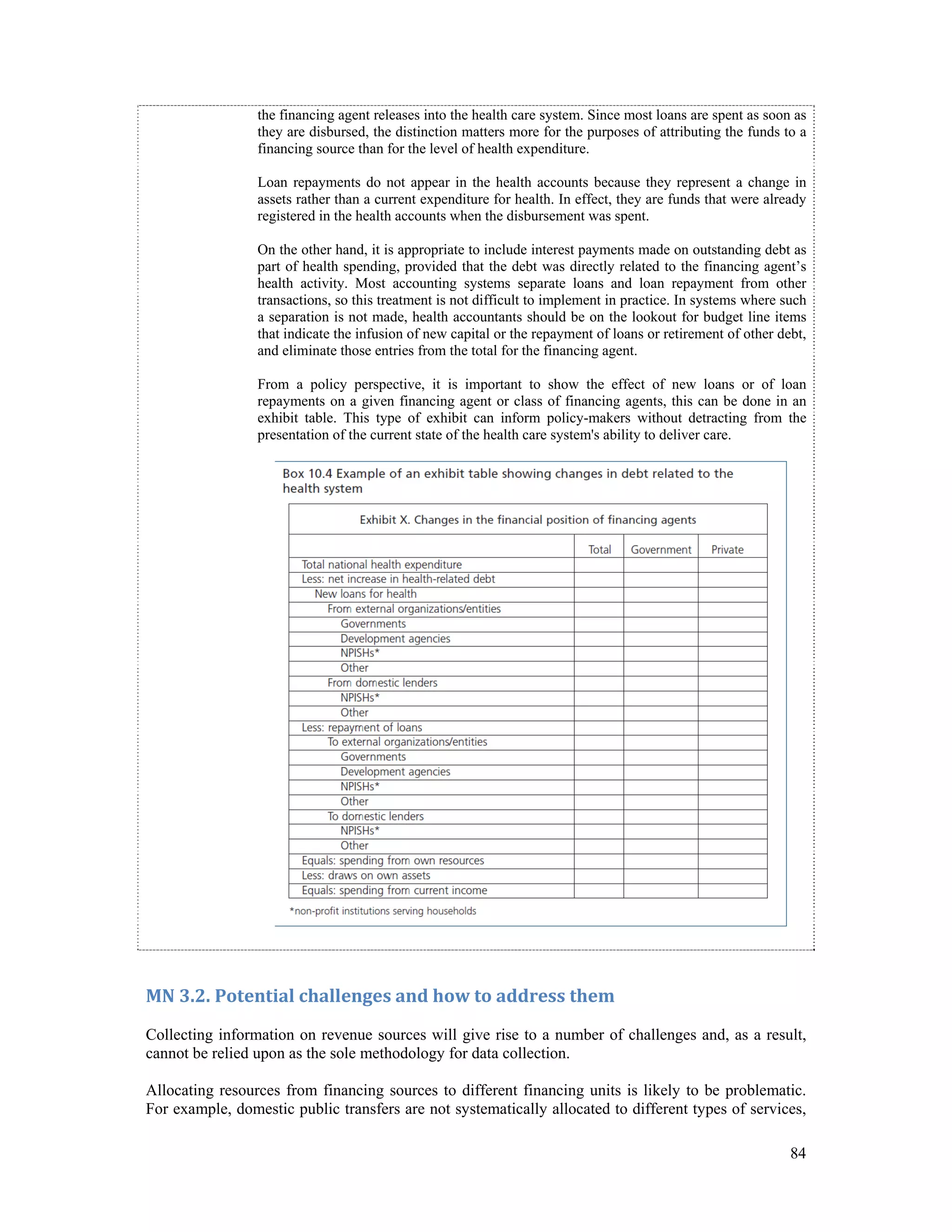

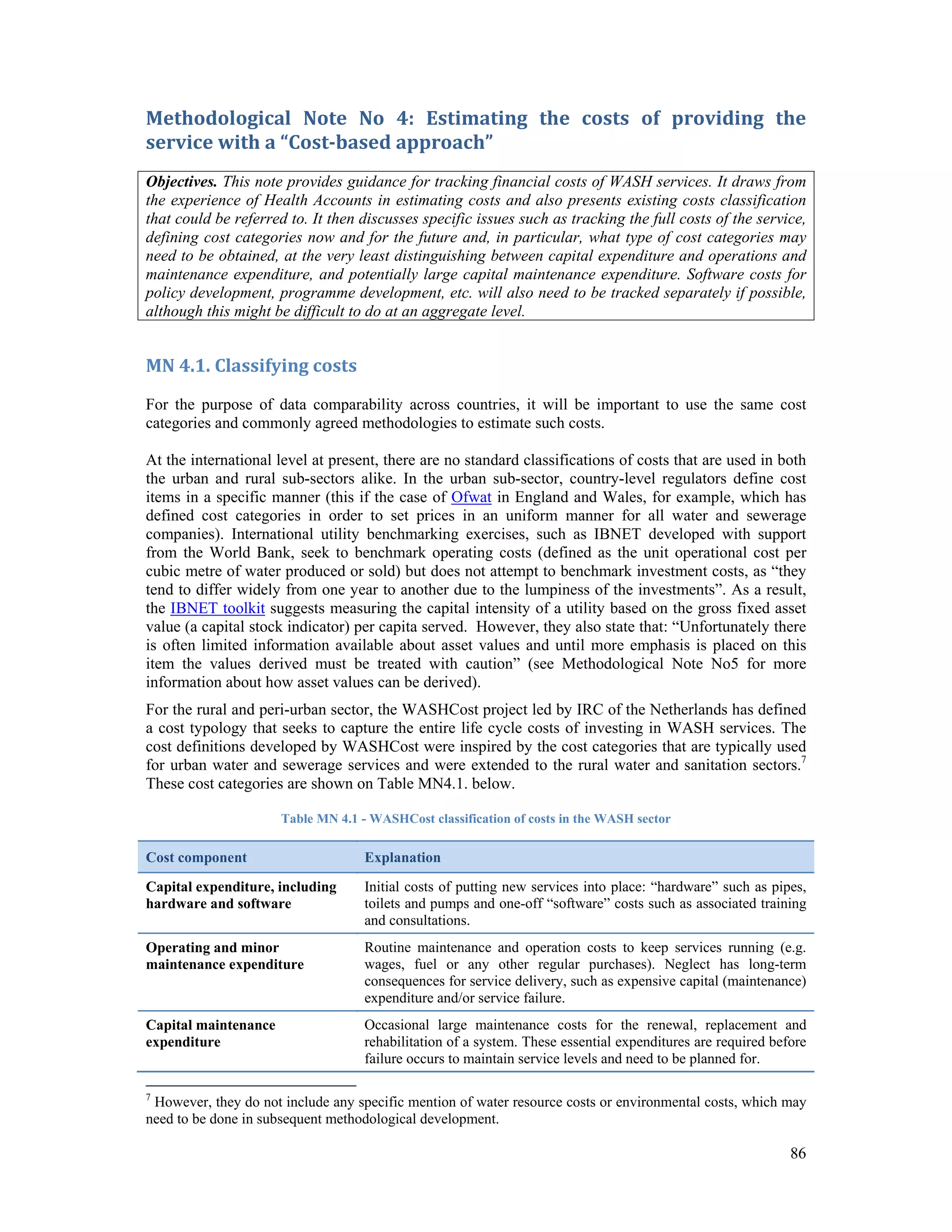

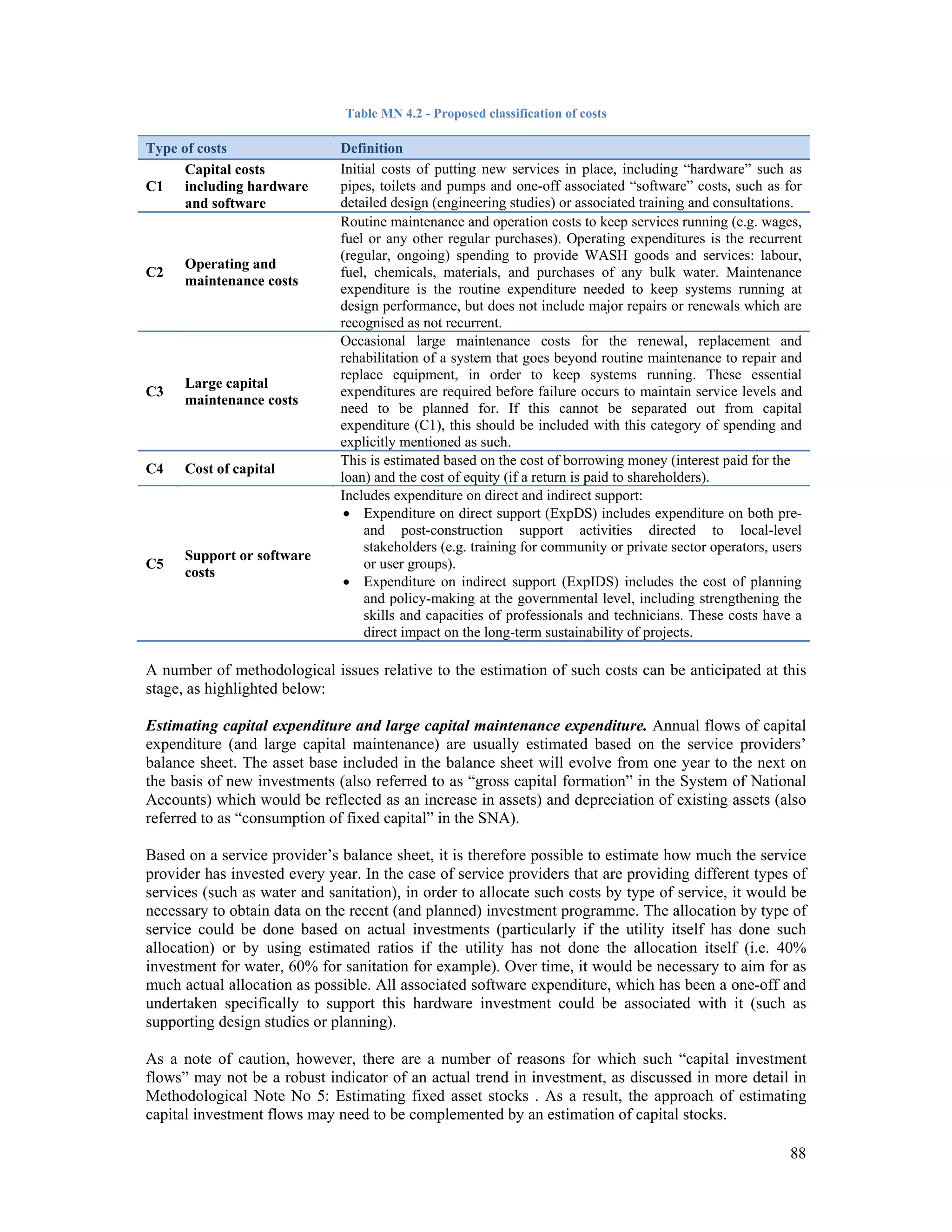

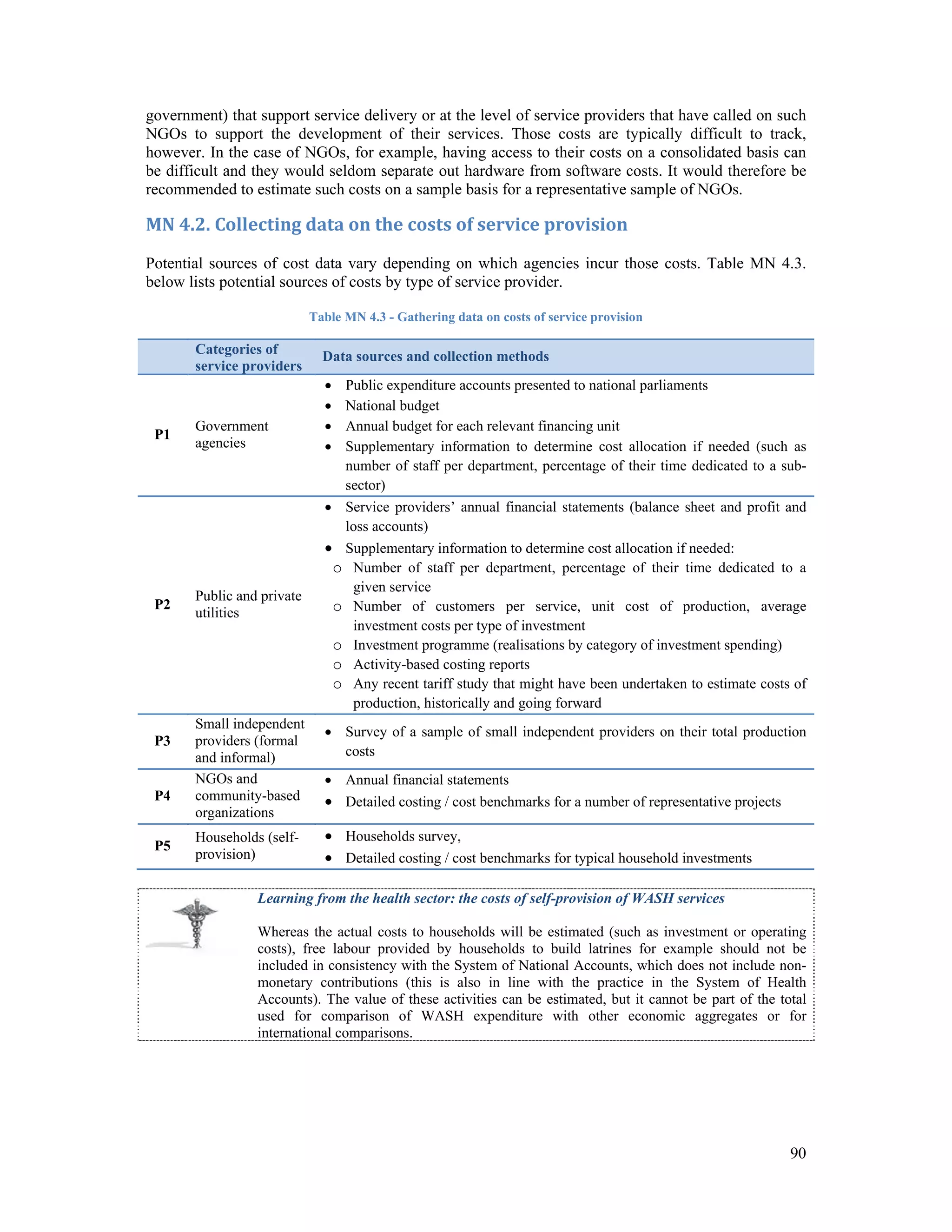

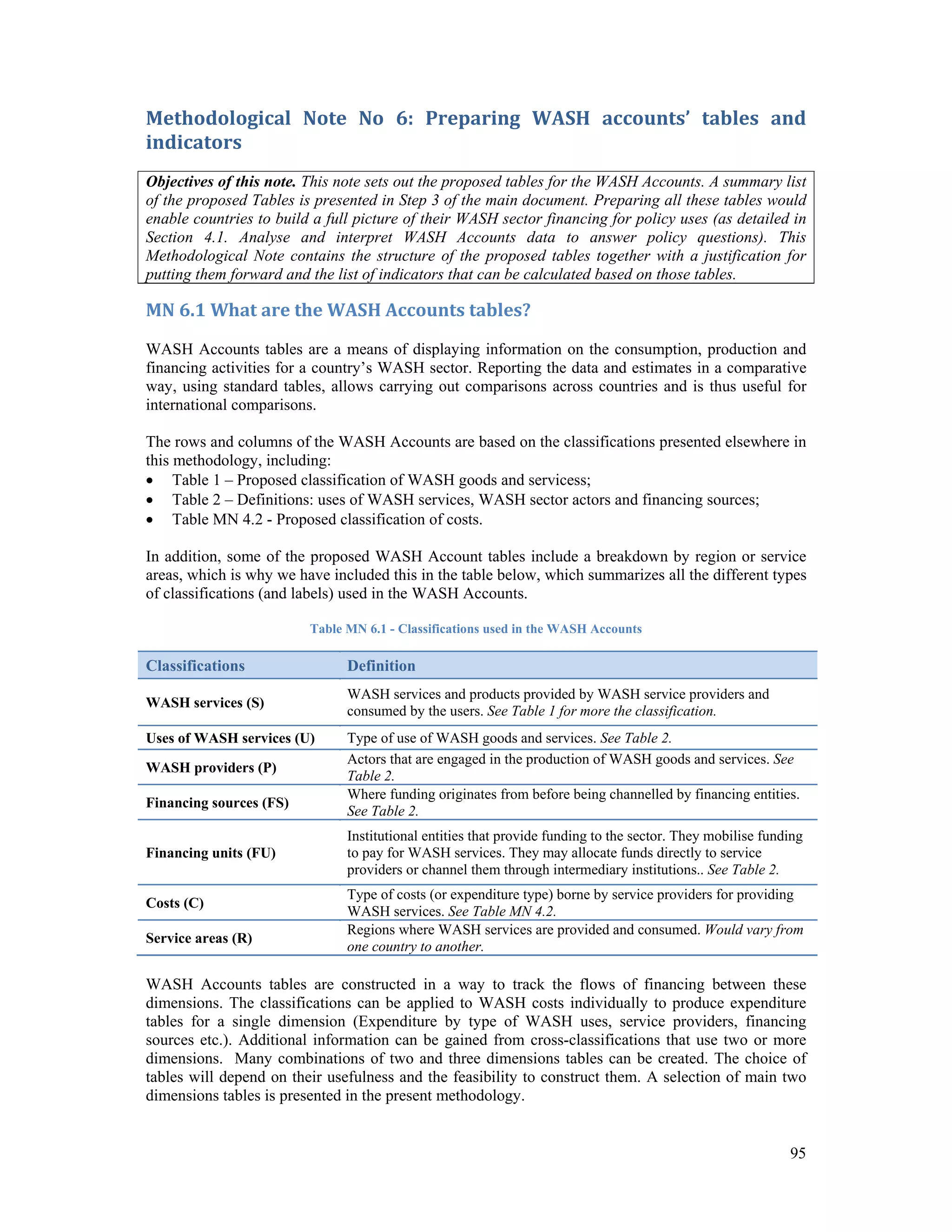

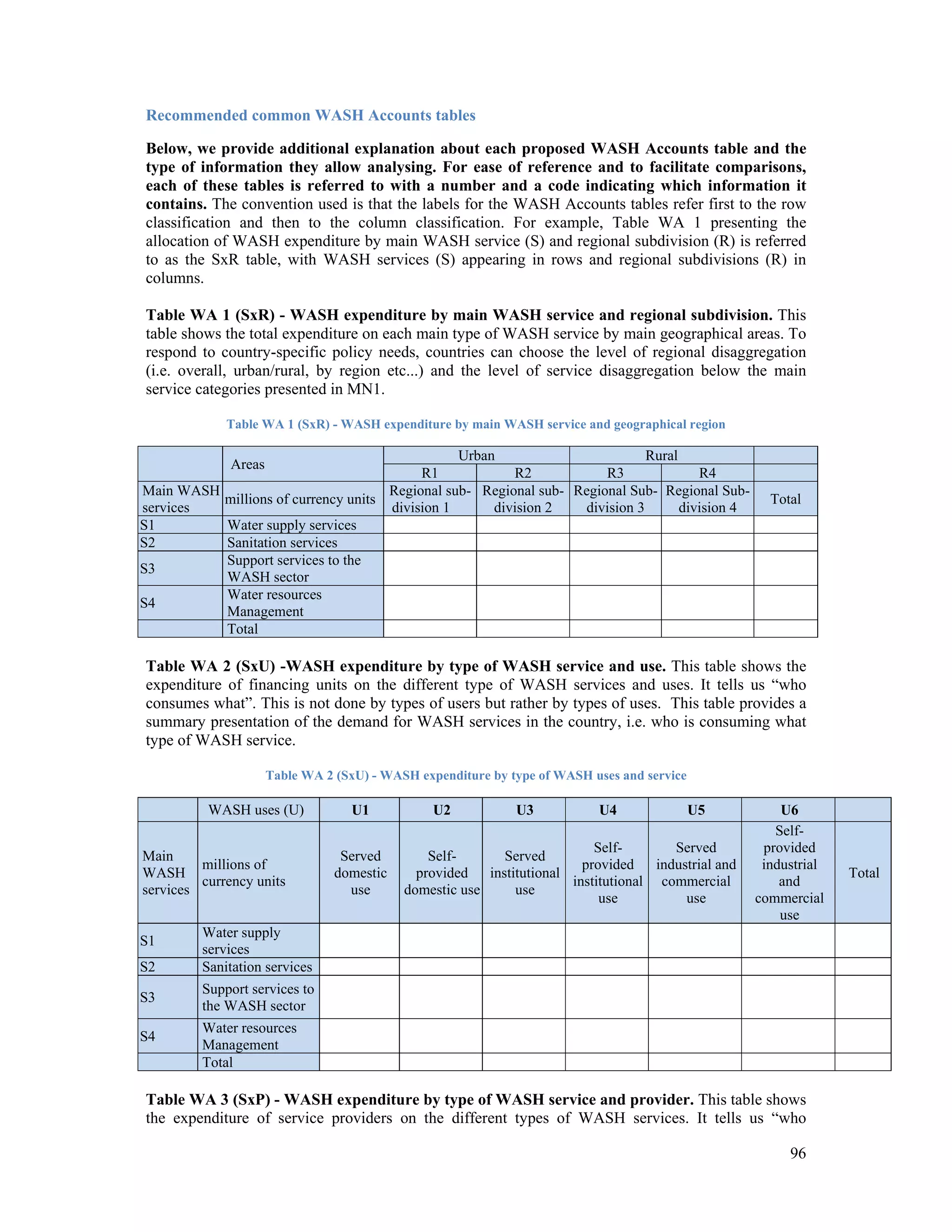

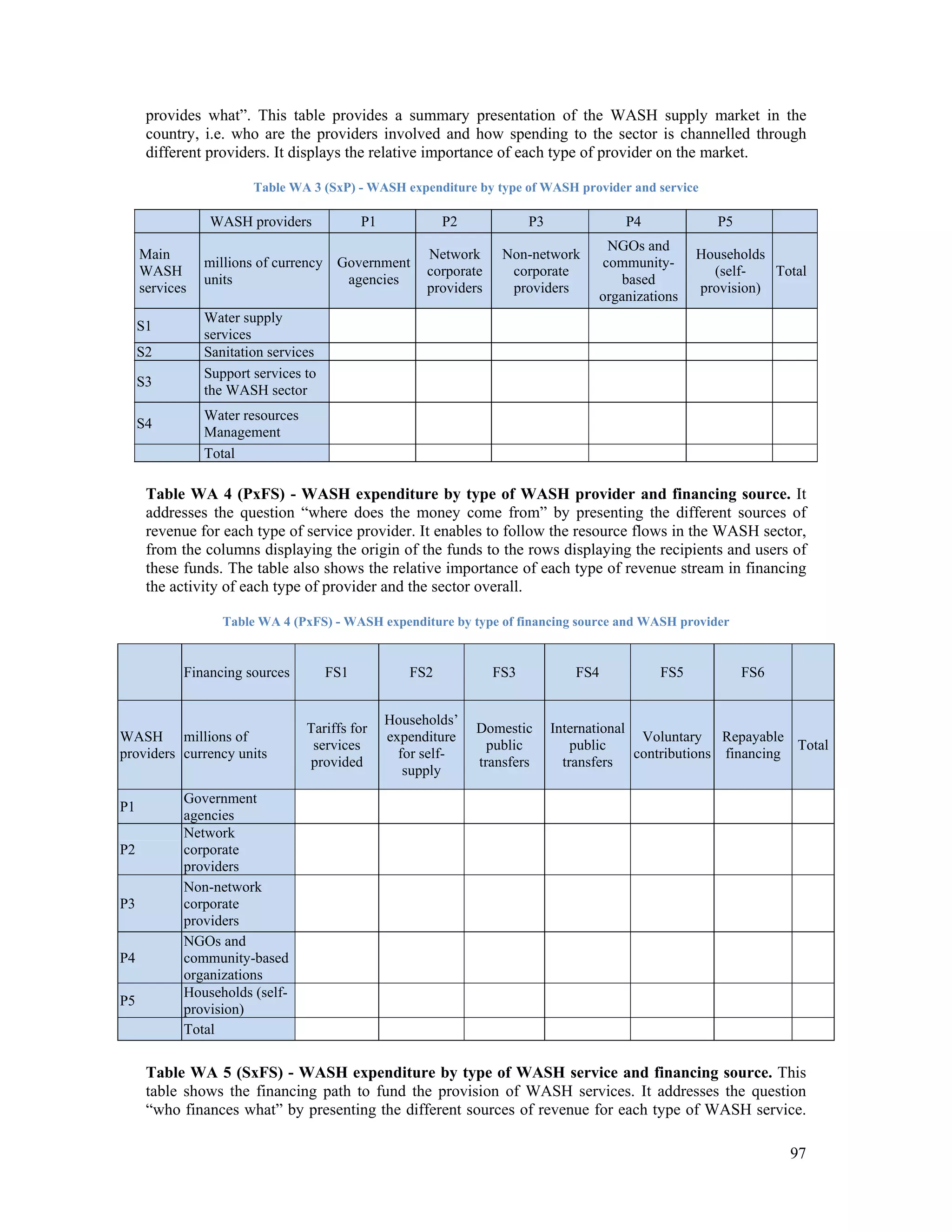

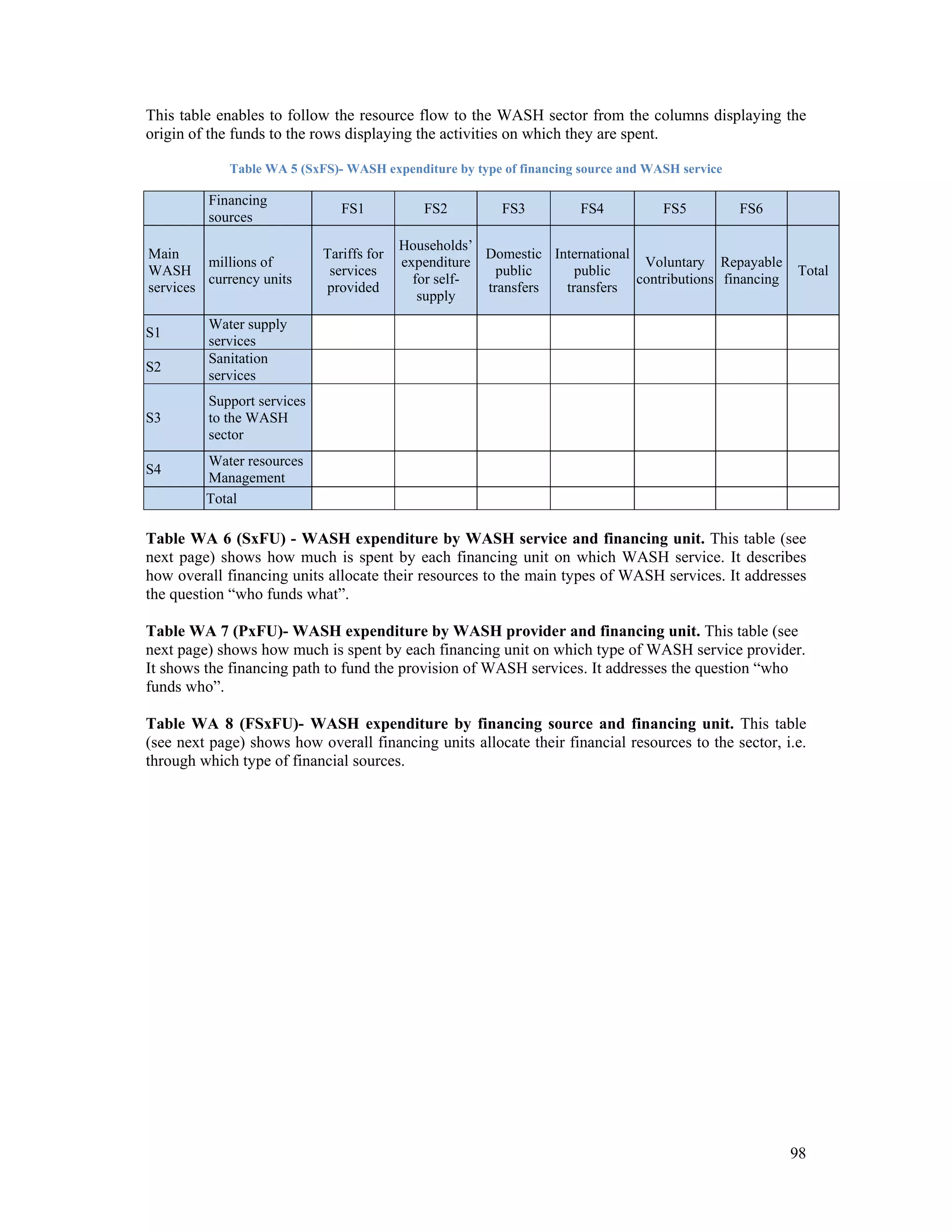

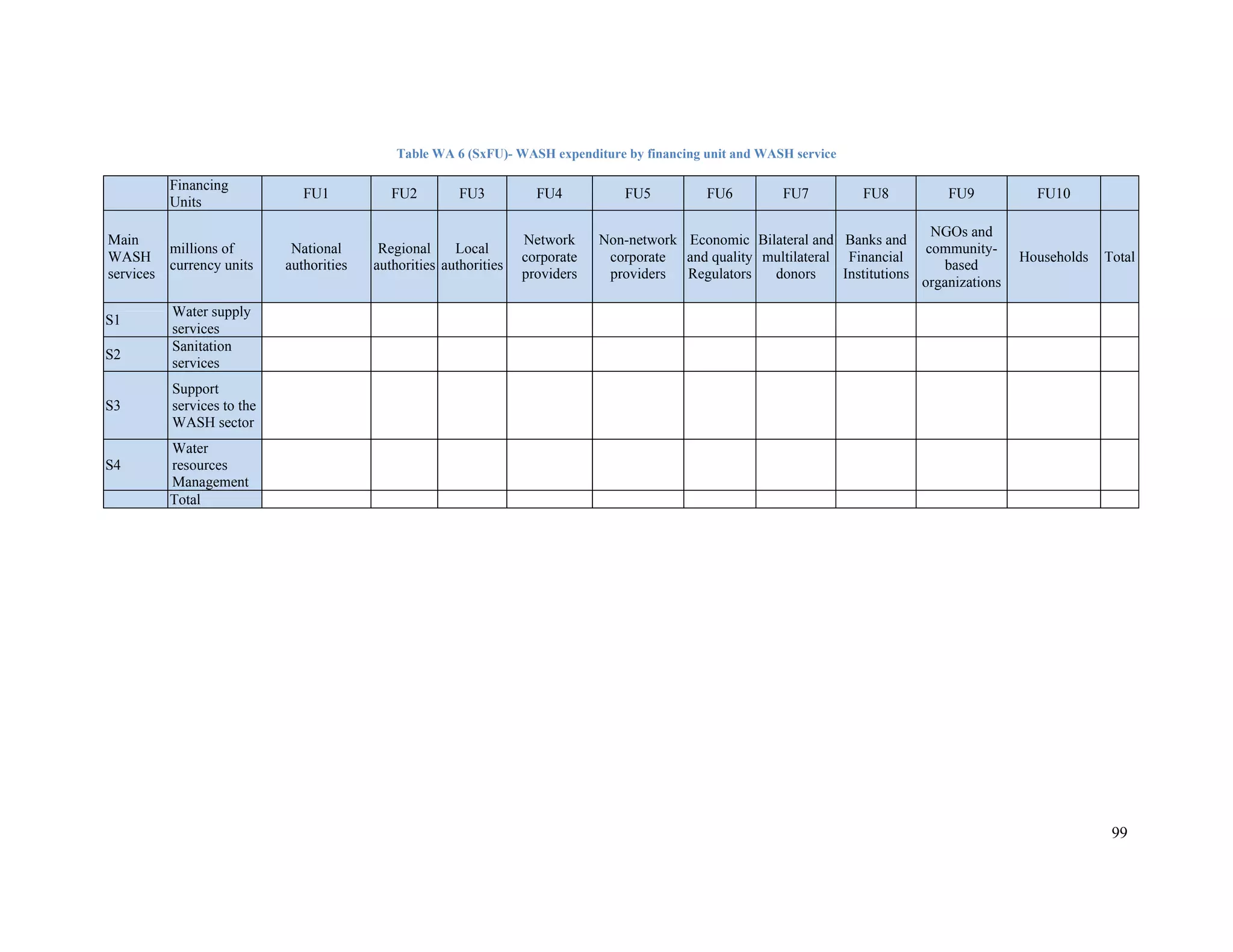

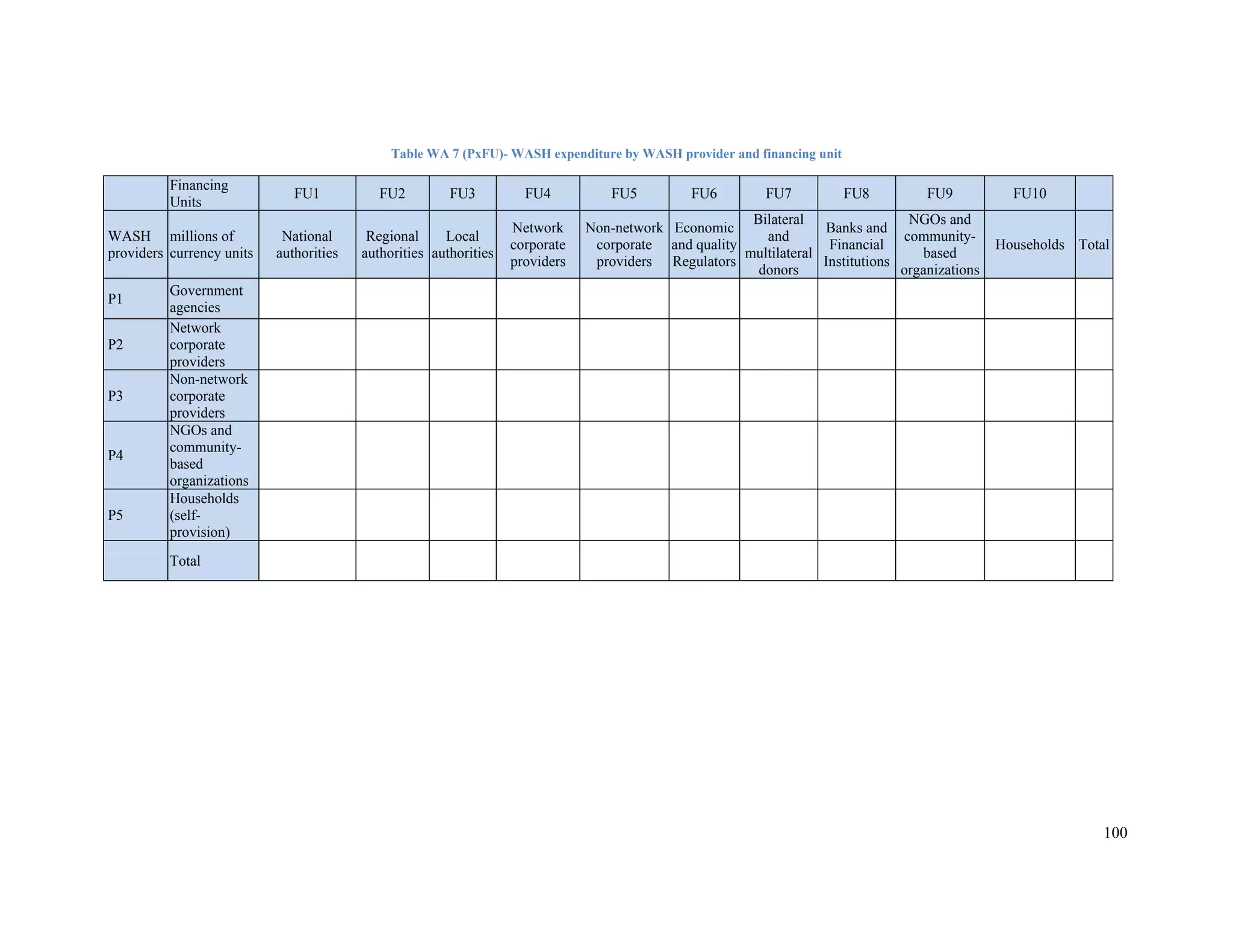

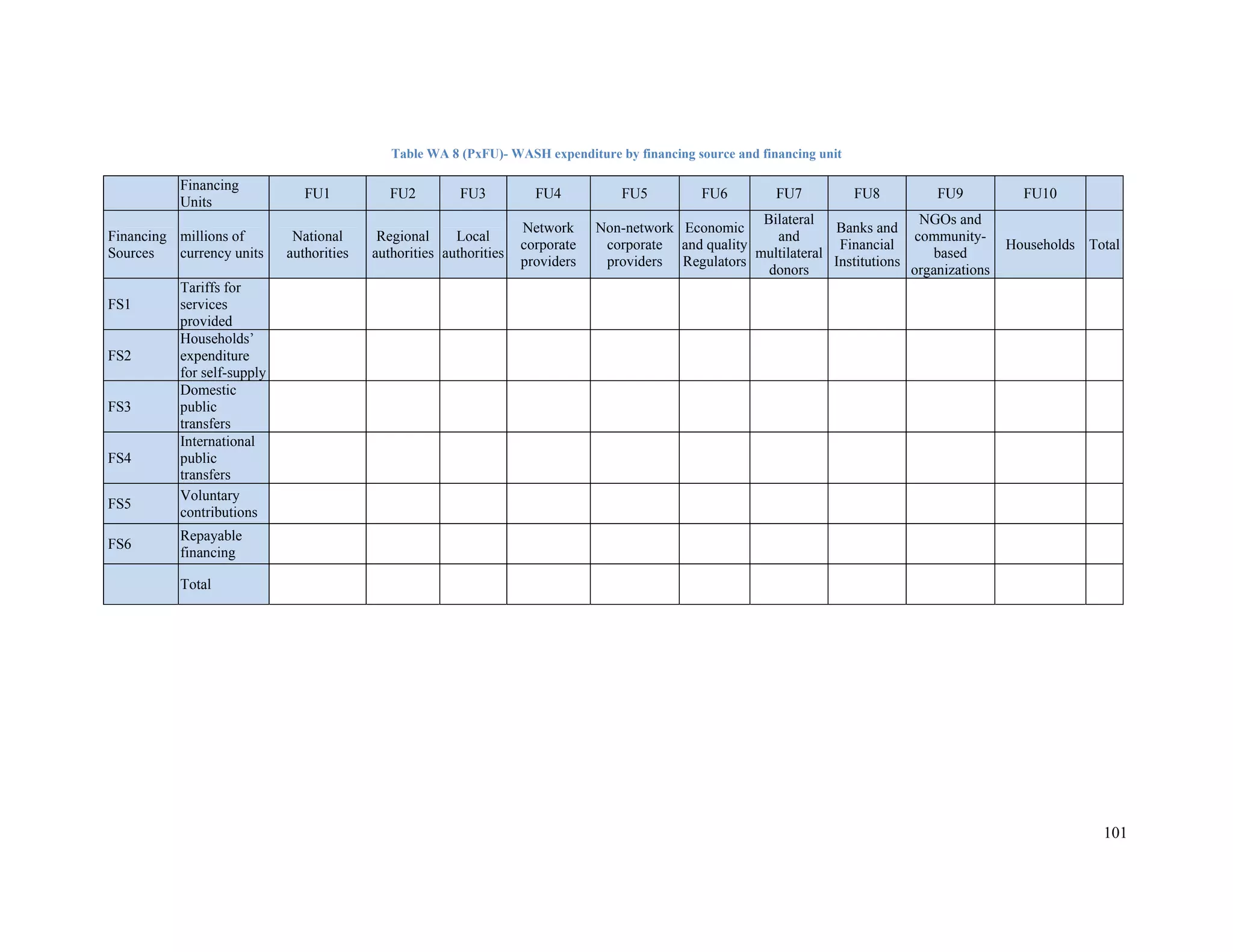

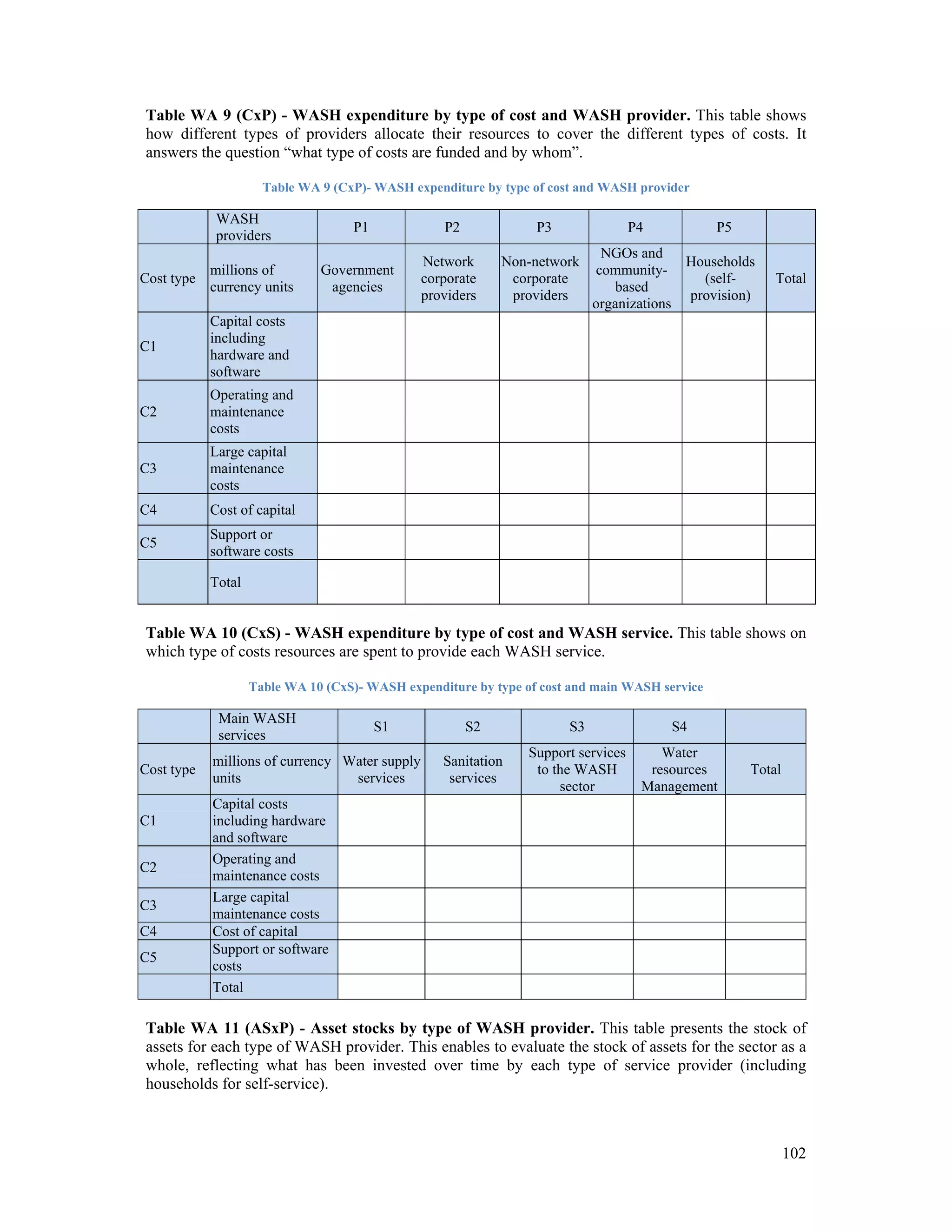

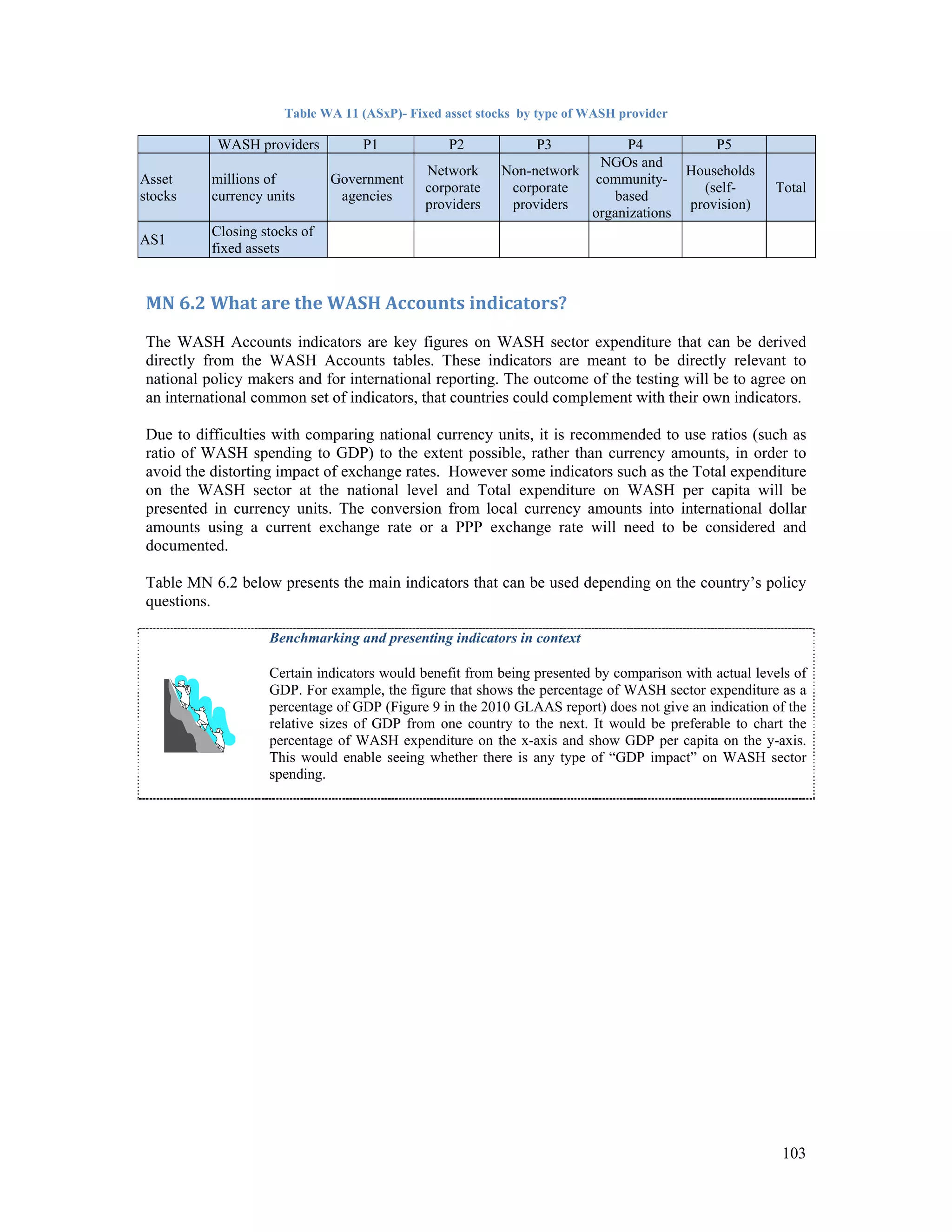

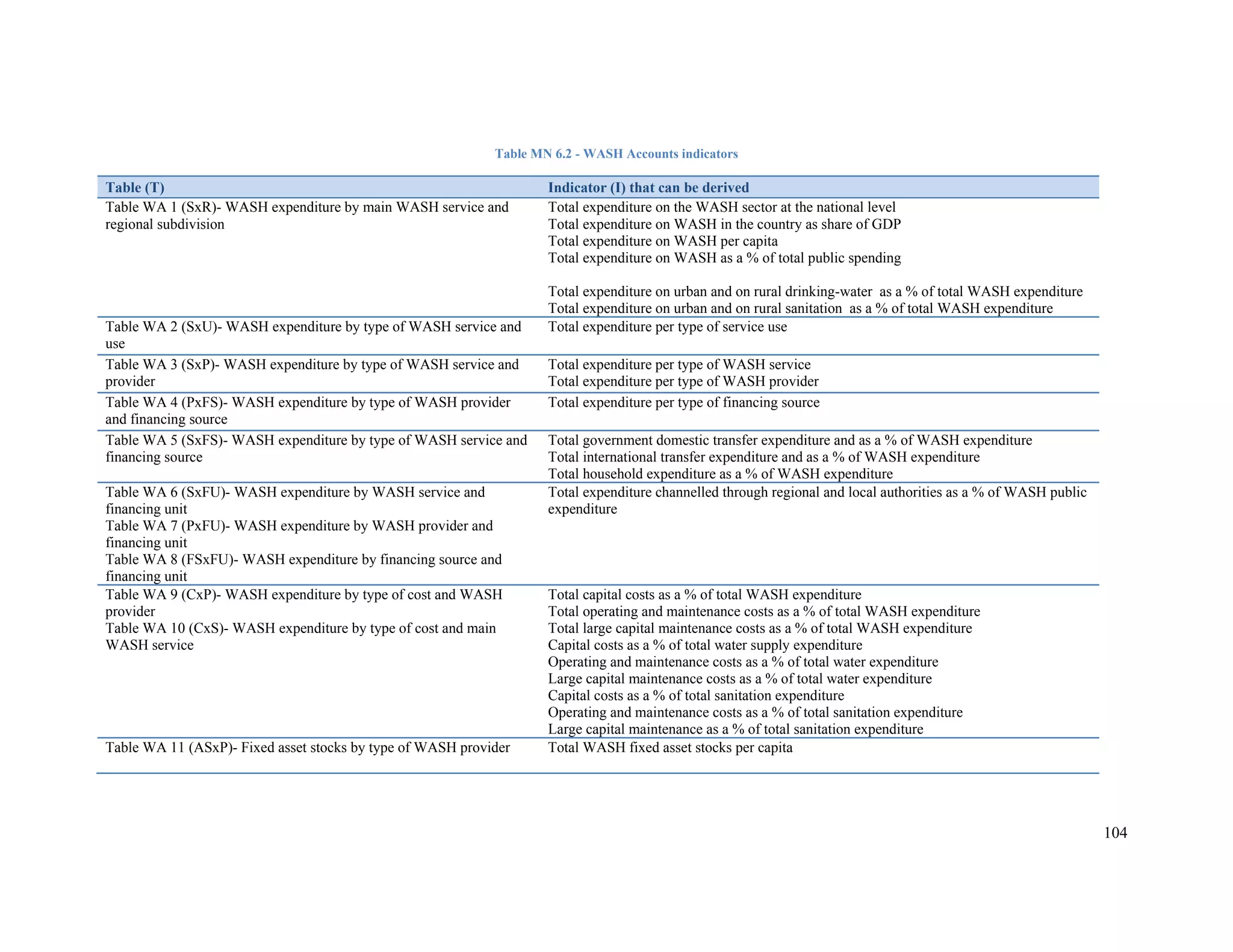

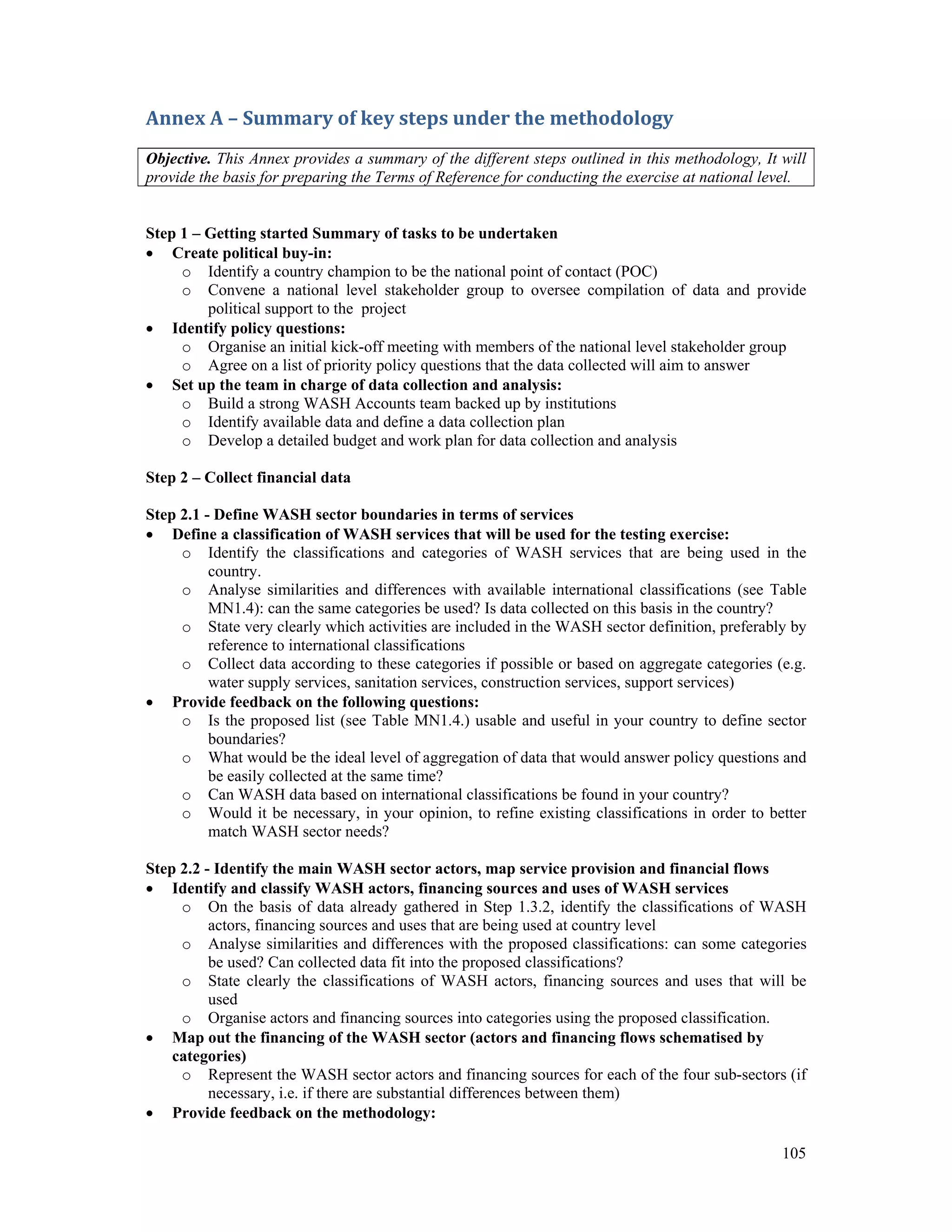

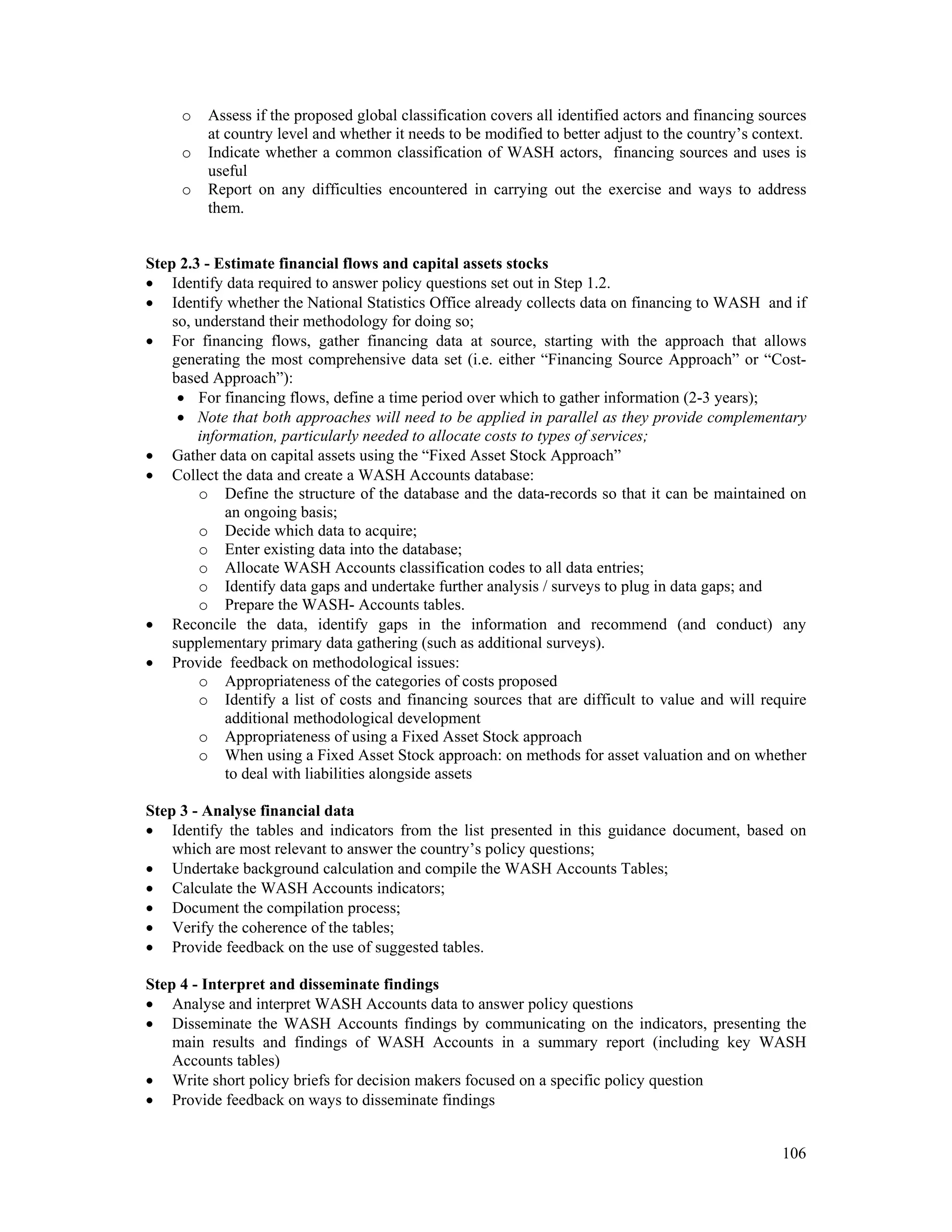

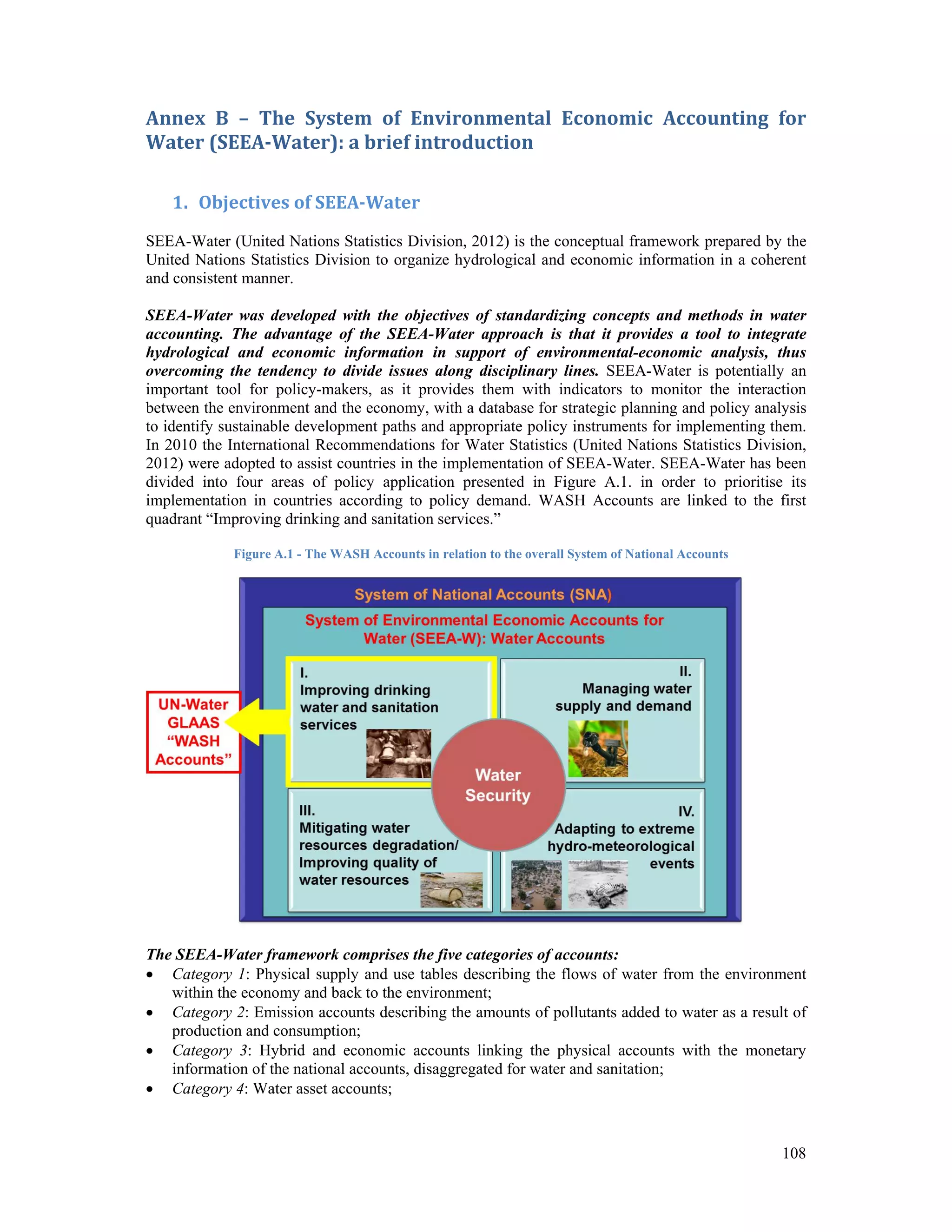

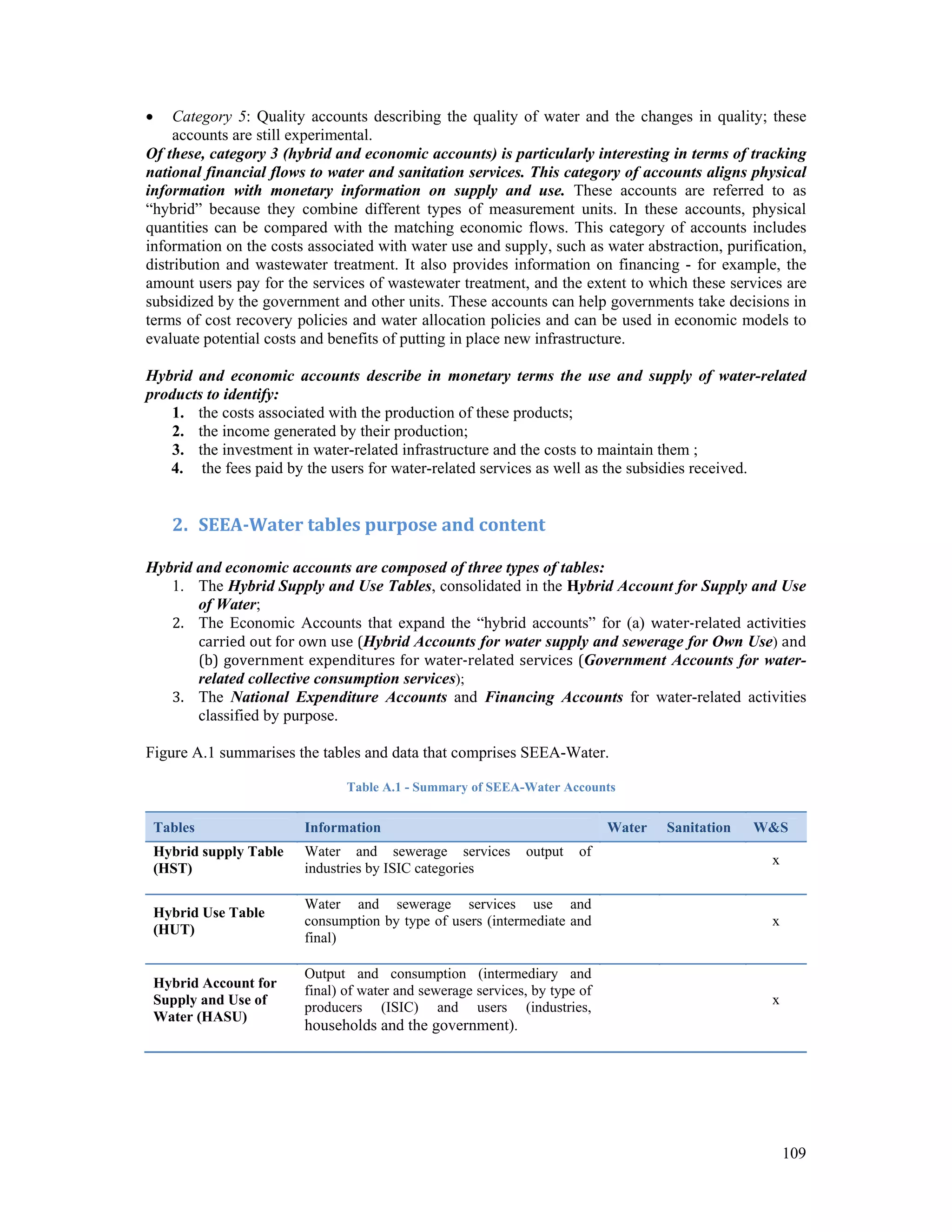

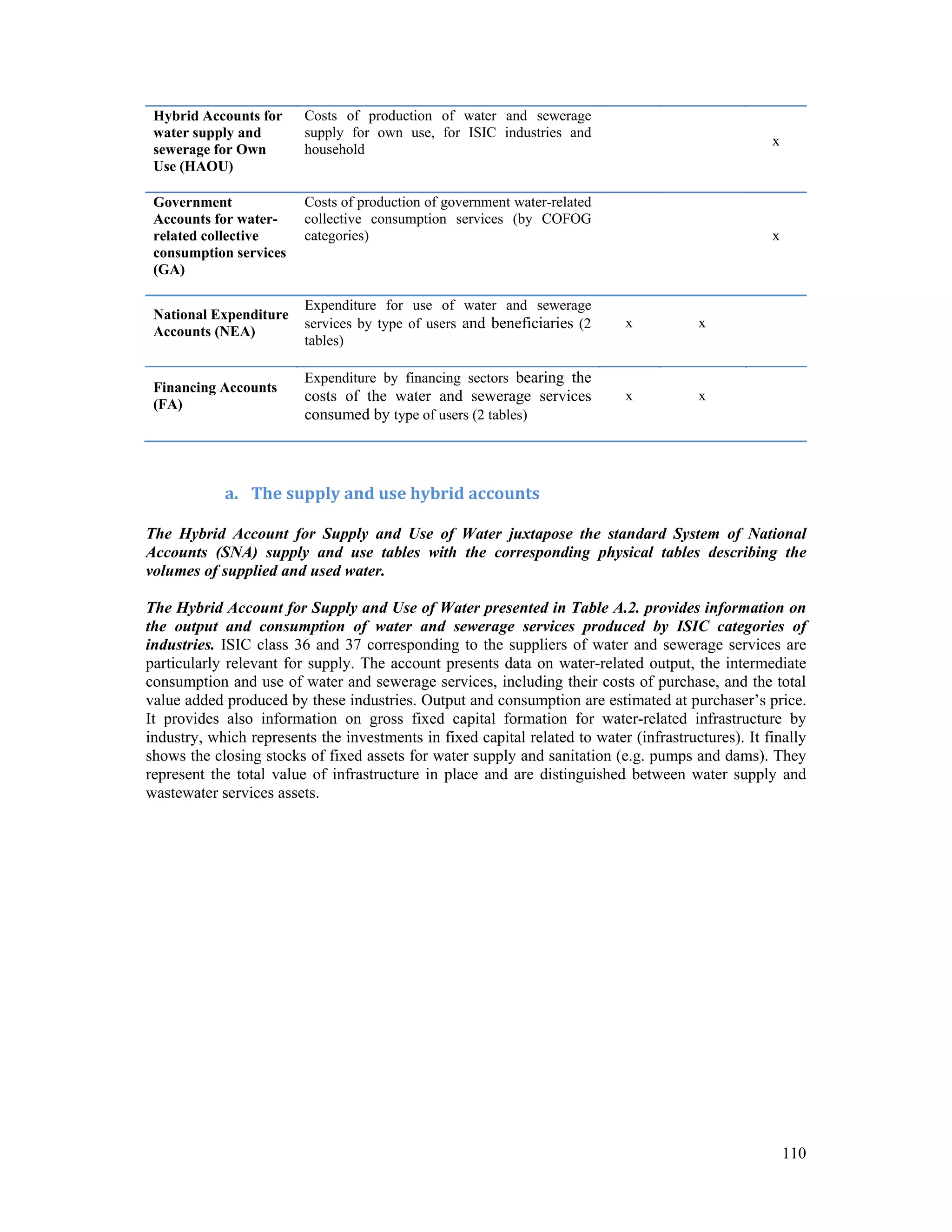

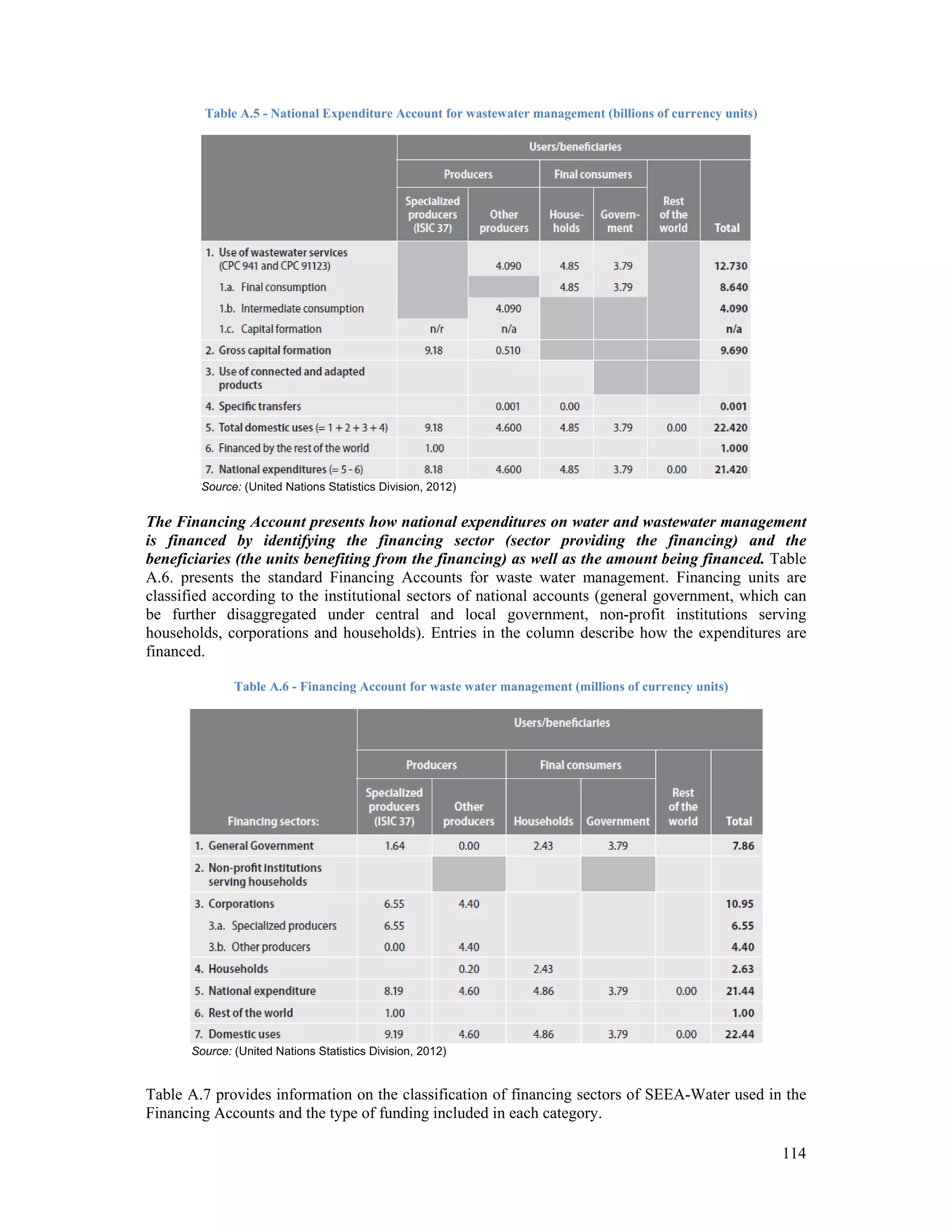

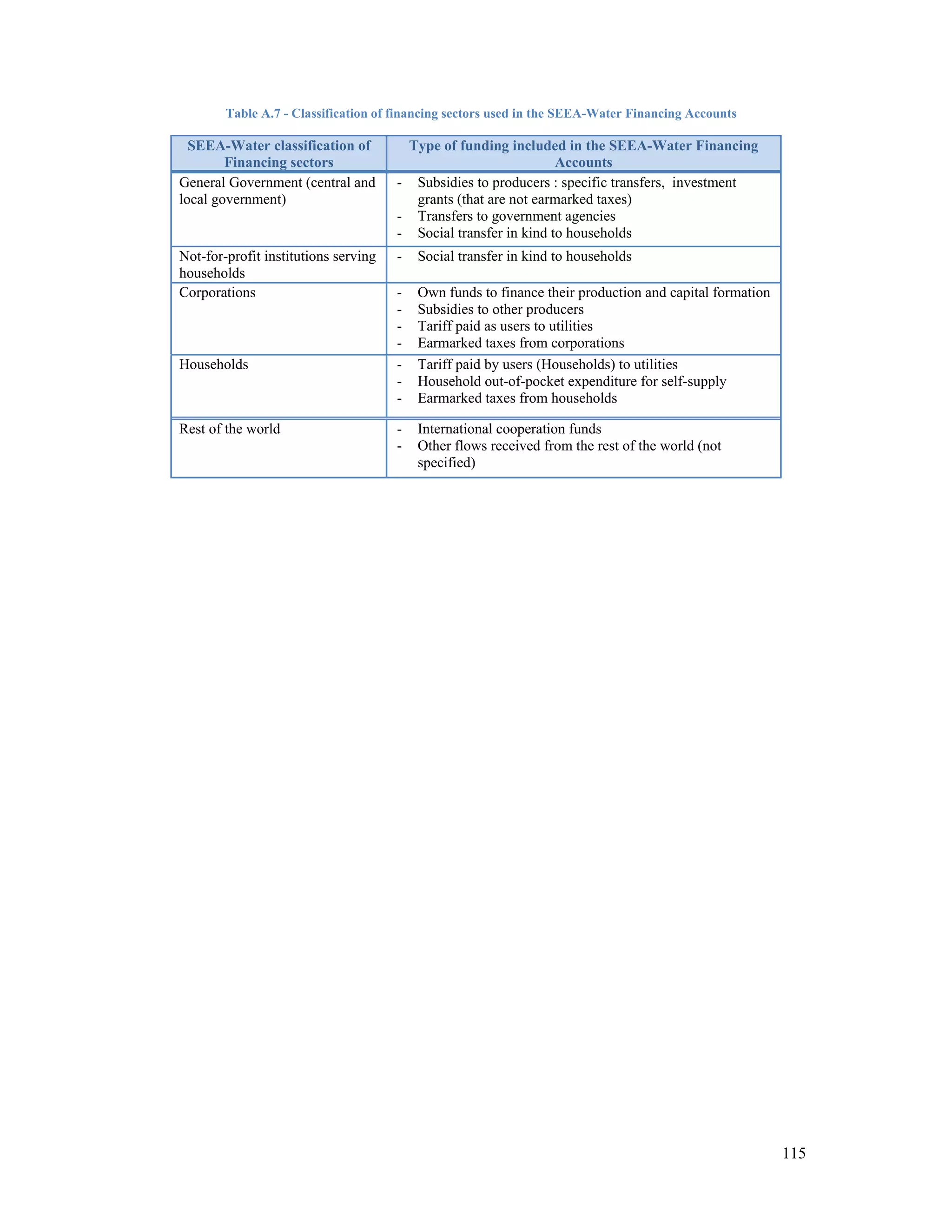

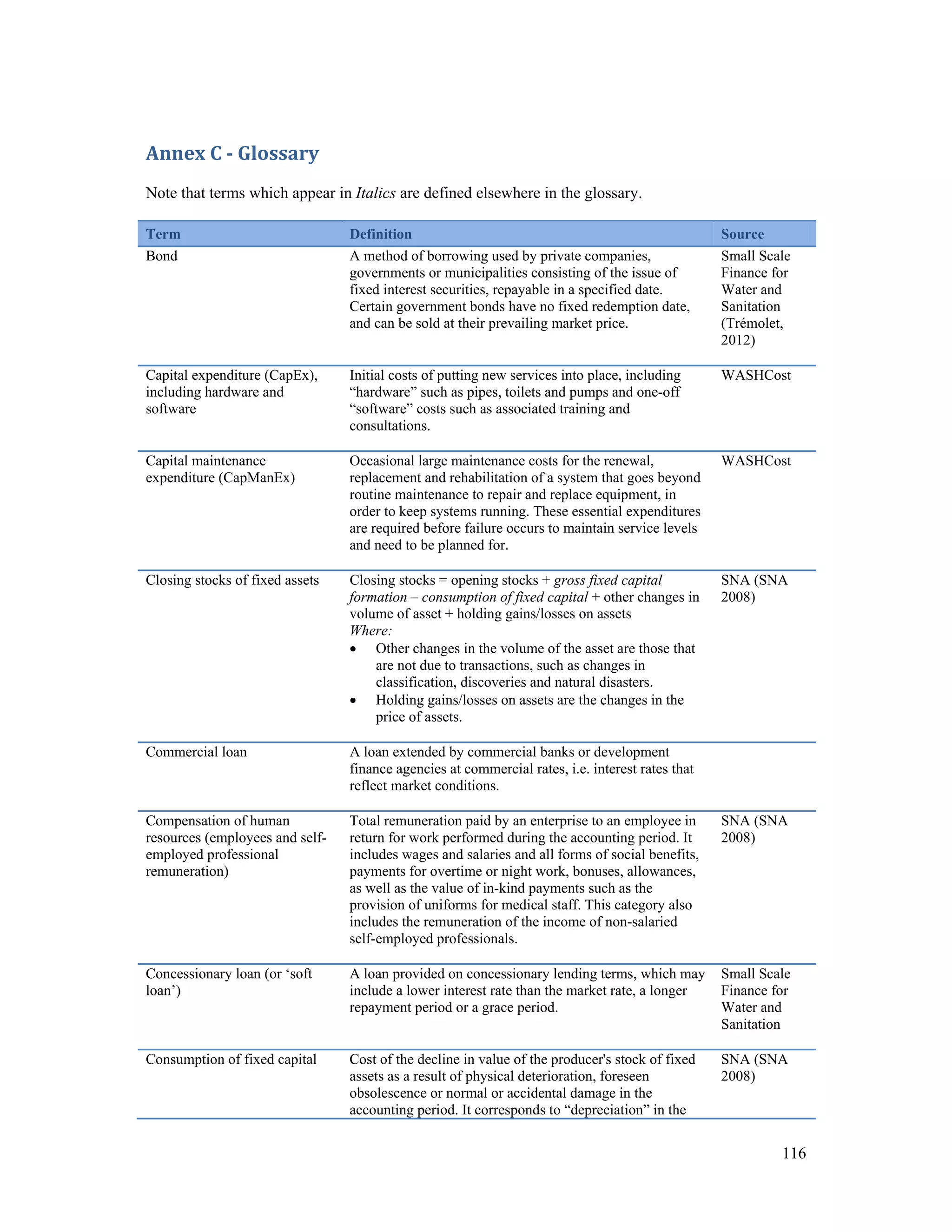

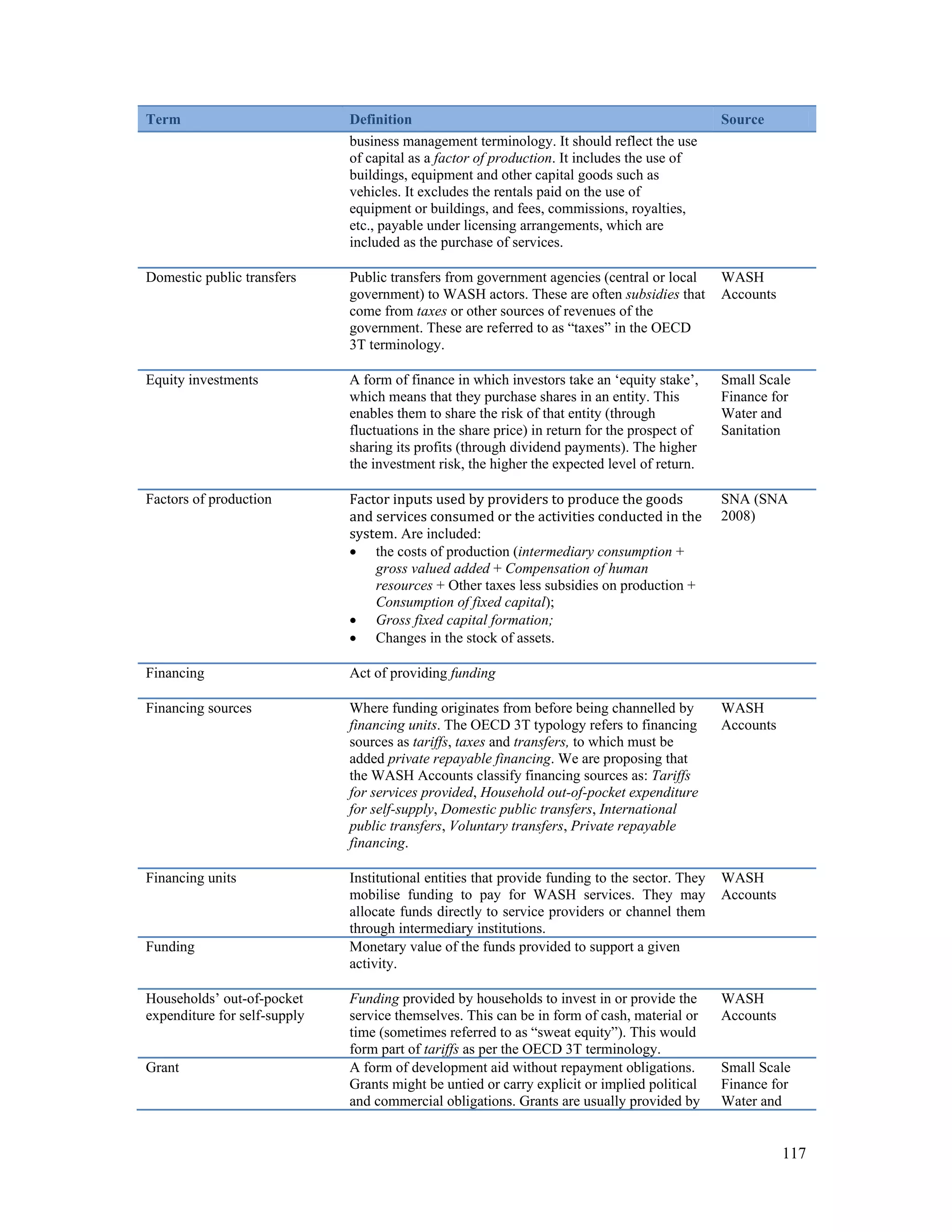

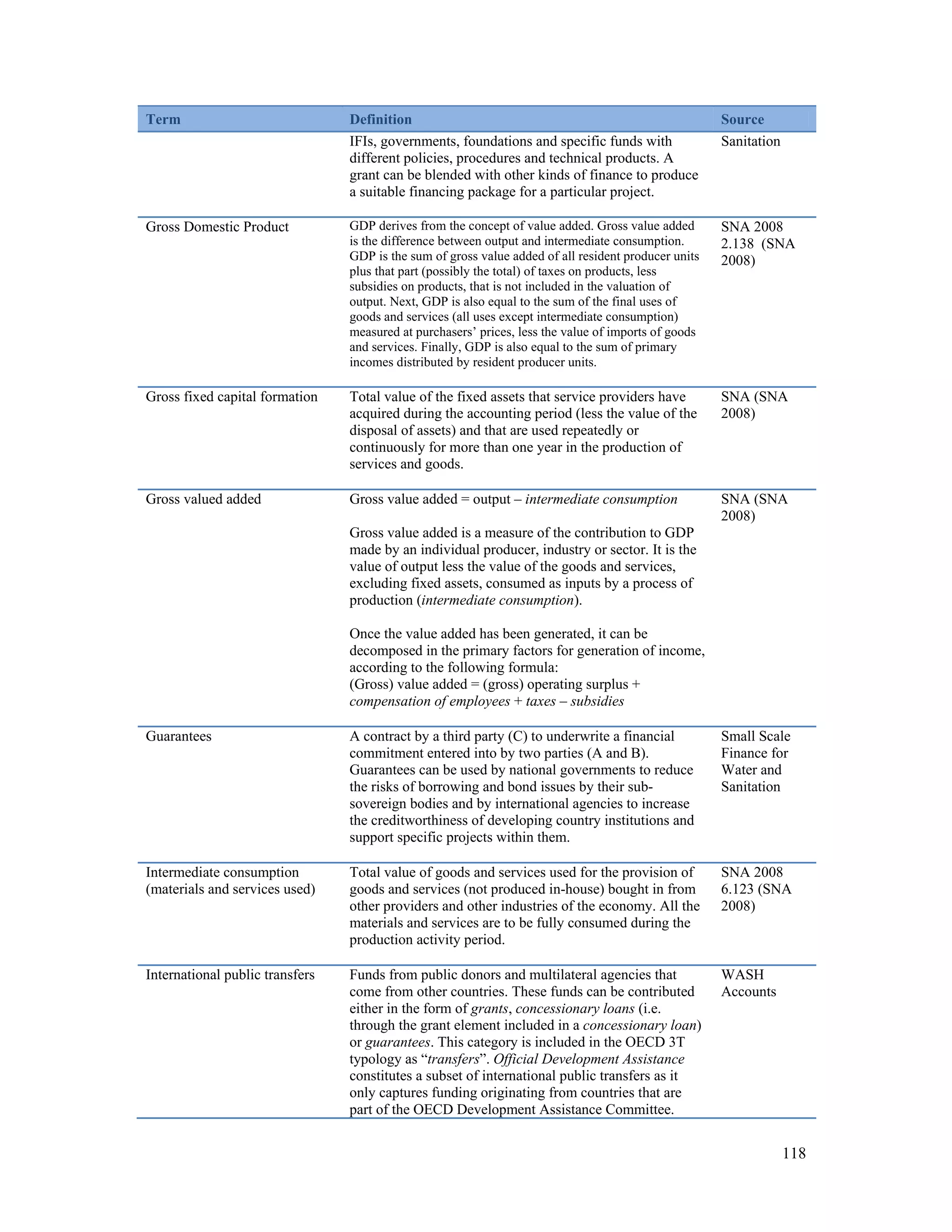

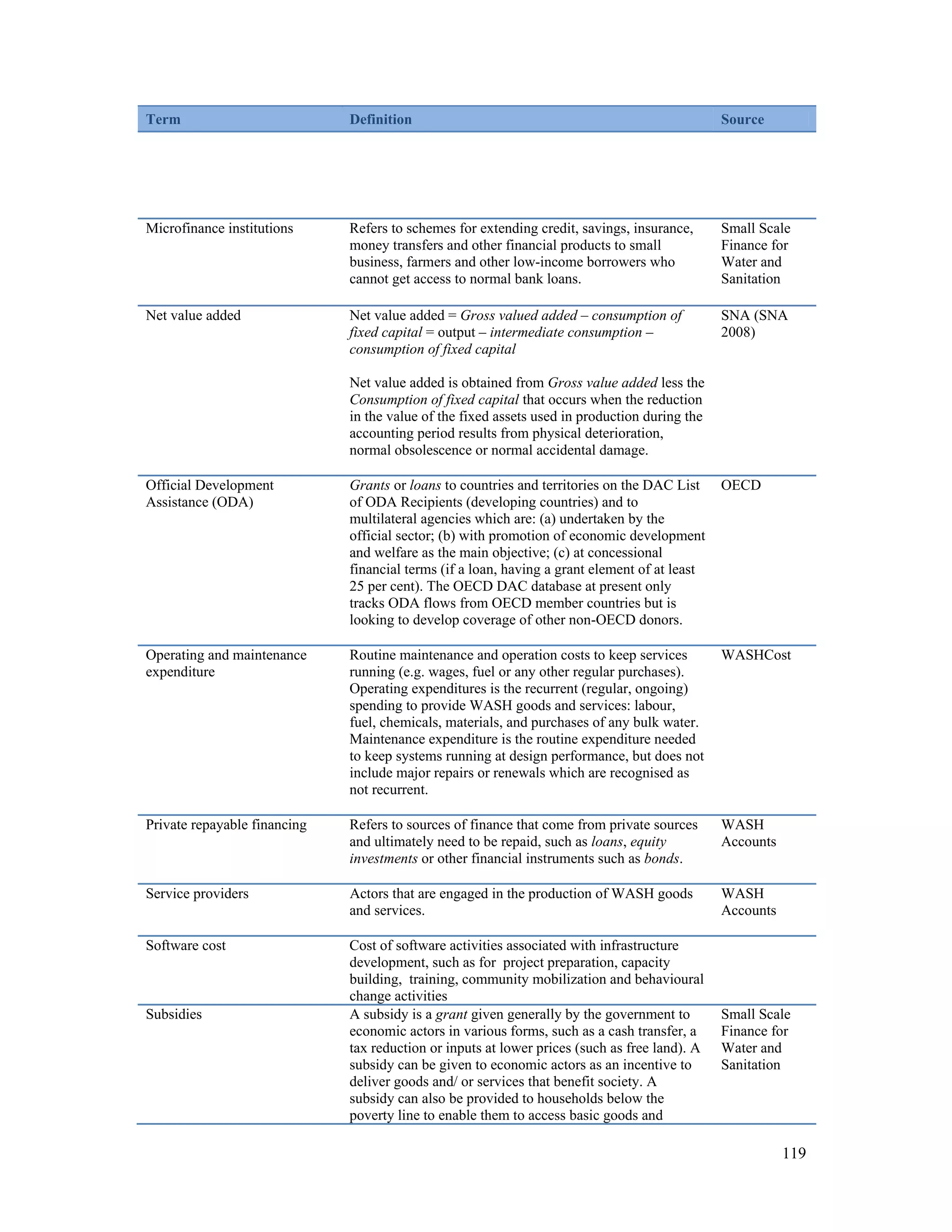

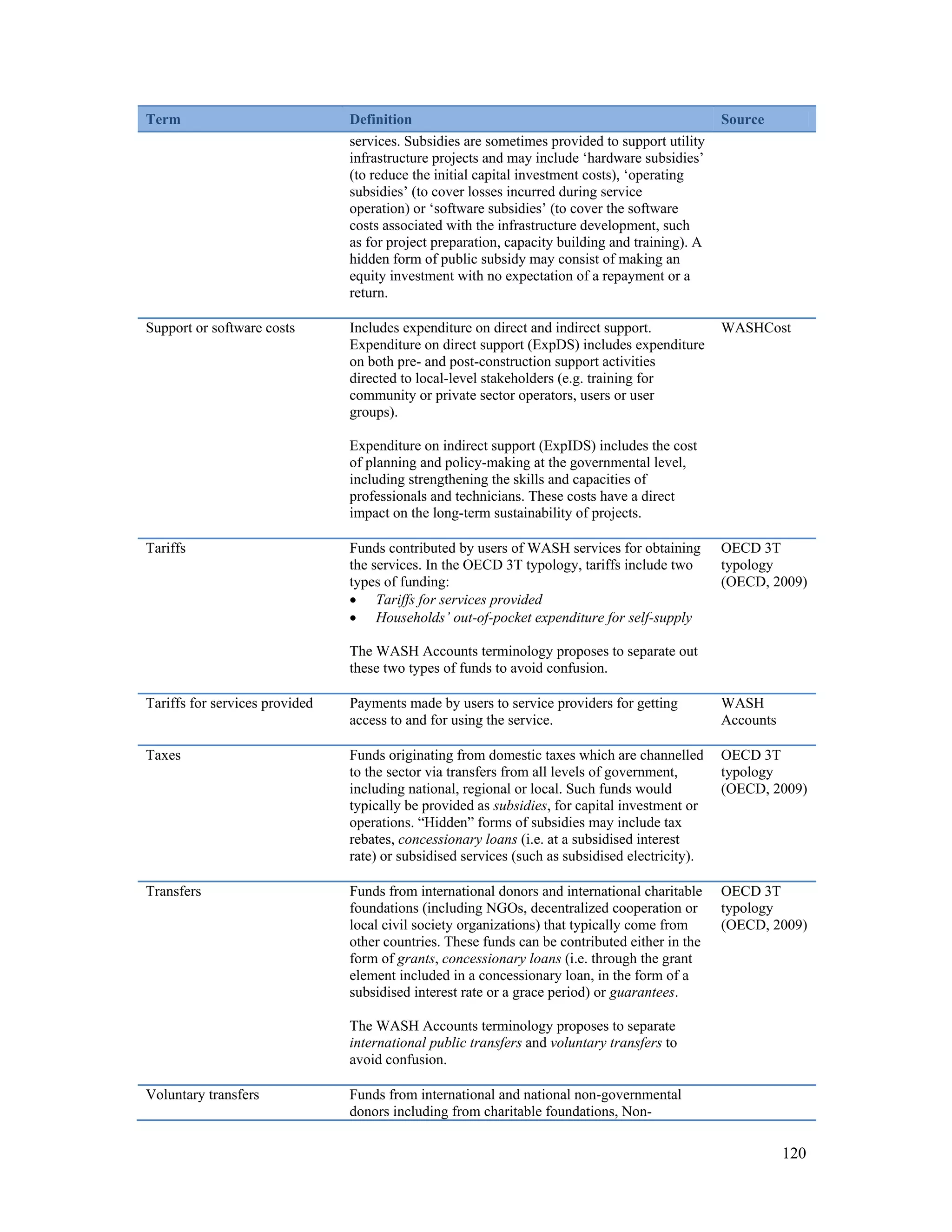

The document outlines a methodology for tracking financing in the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector across countries to support evidence-based policymaking. It addresses existing gaps in financial data availability and aims to create comparable WASH accounts to assist in planning and allocation of resources. The process includes steps for data collection, analysis, and dissemination of findings to improve financial transparency and aid in policy development.