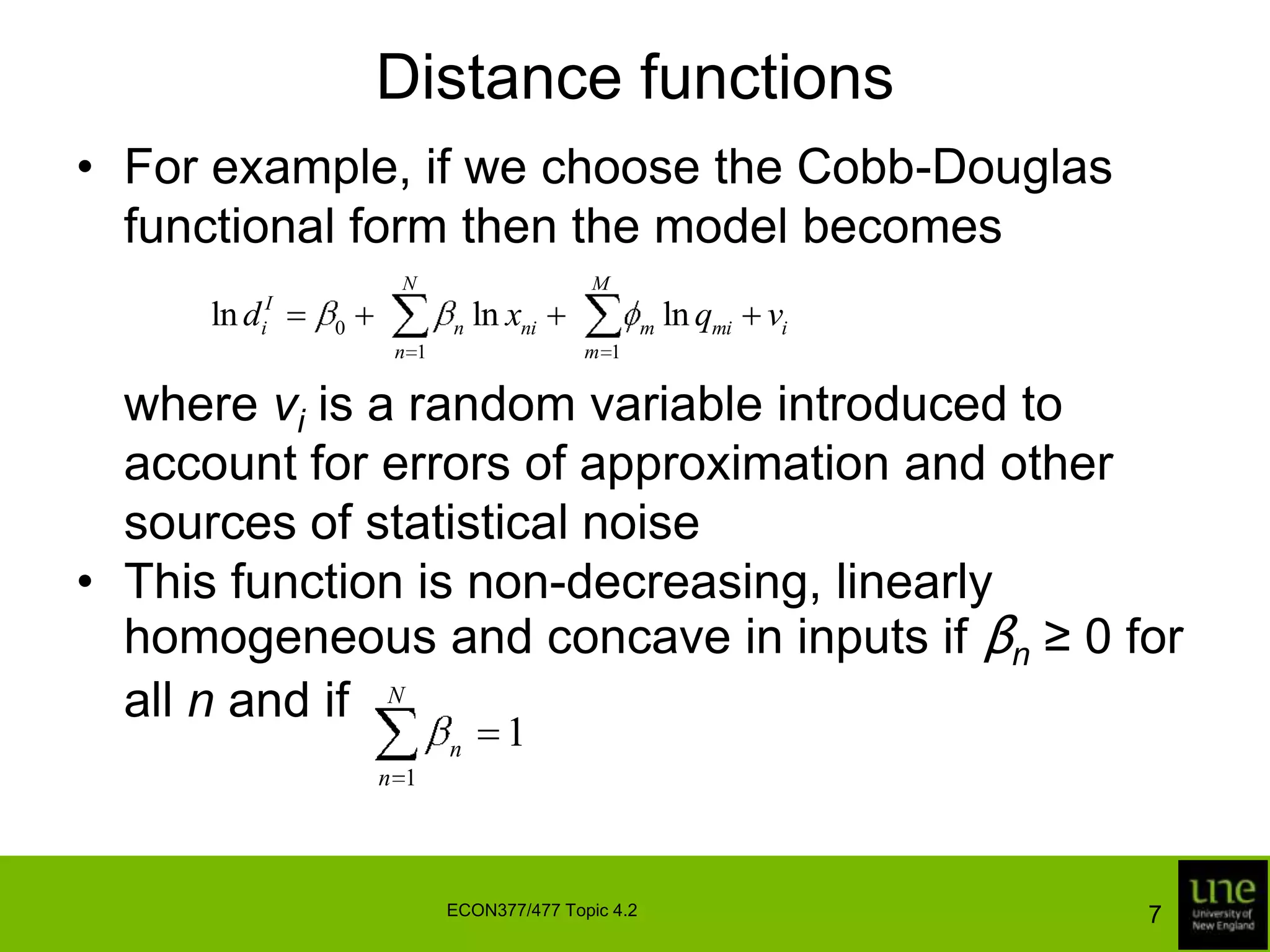

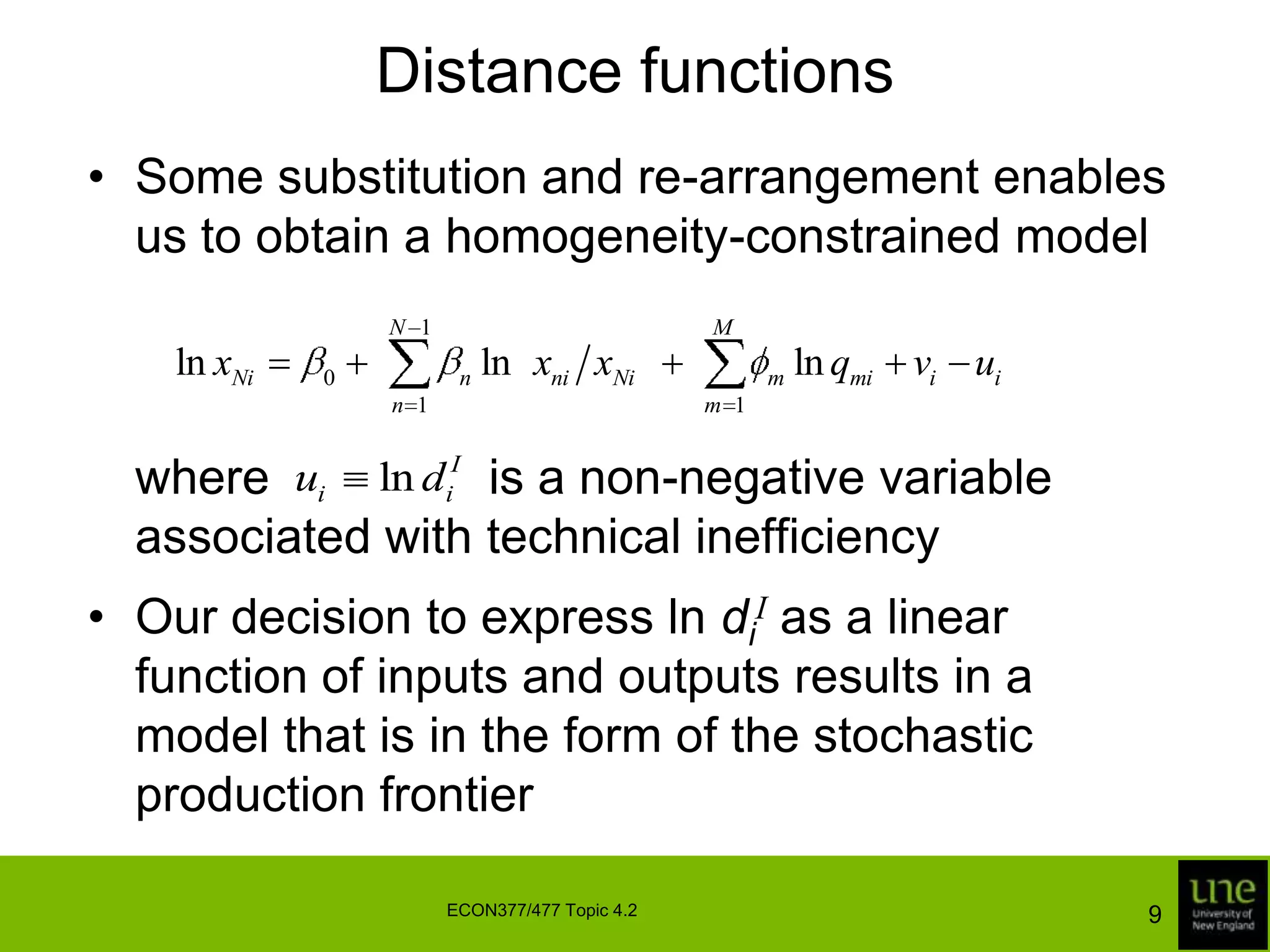

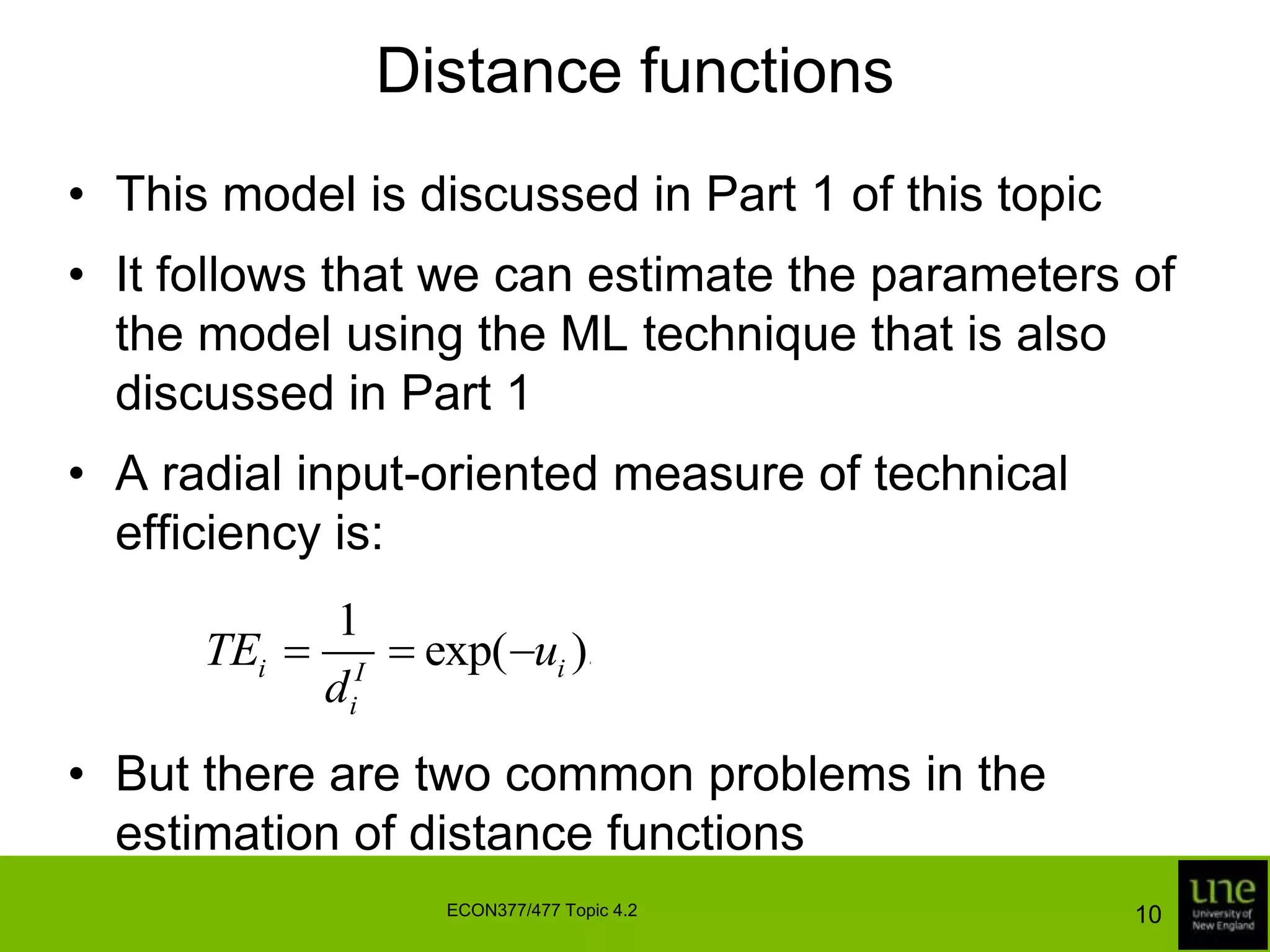

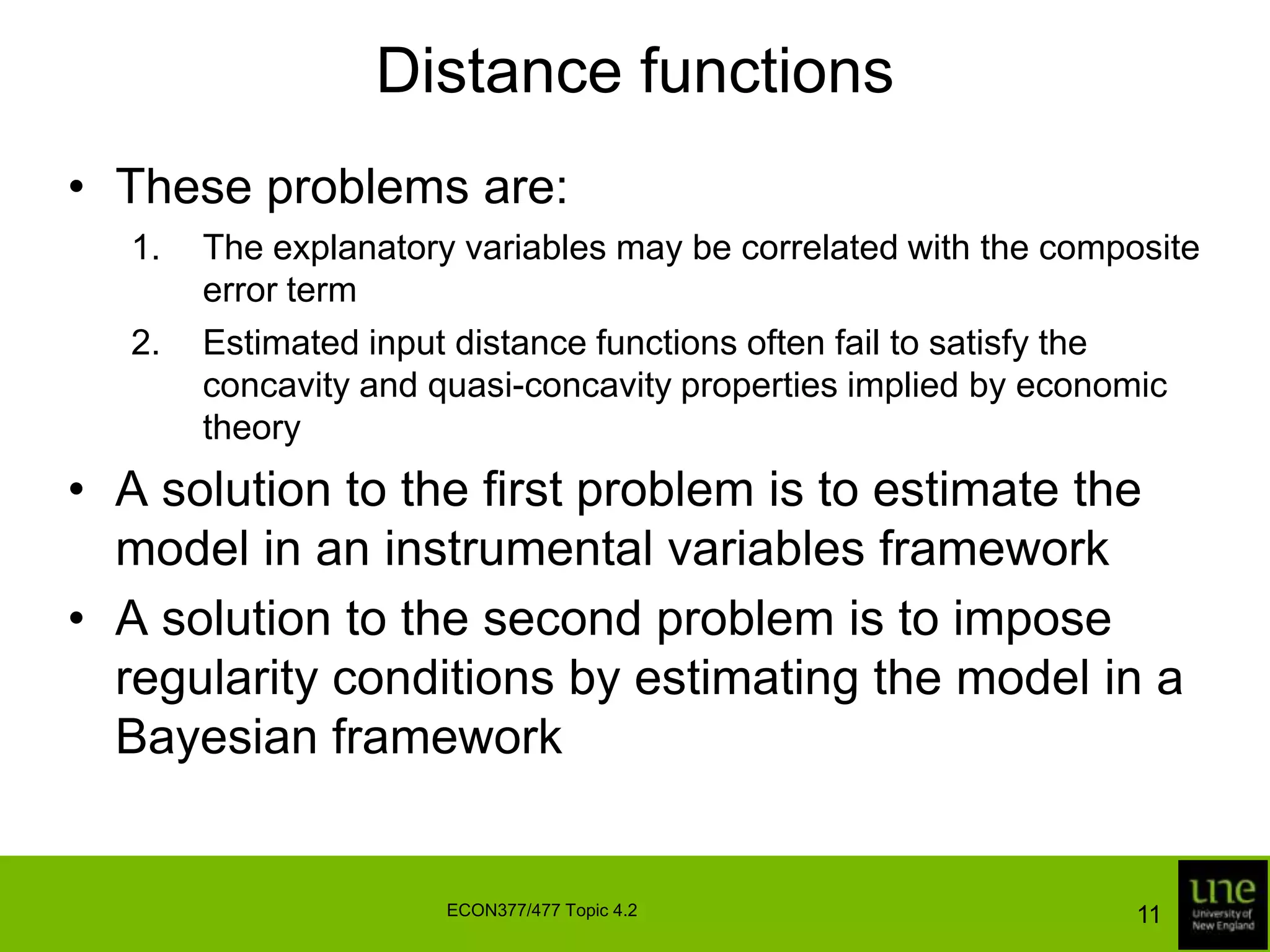

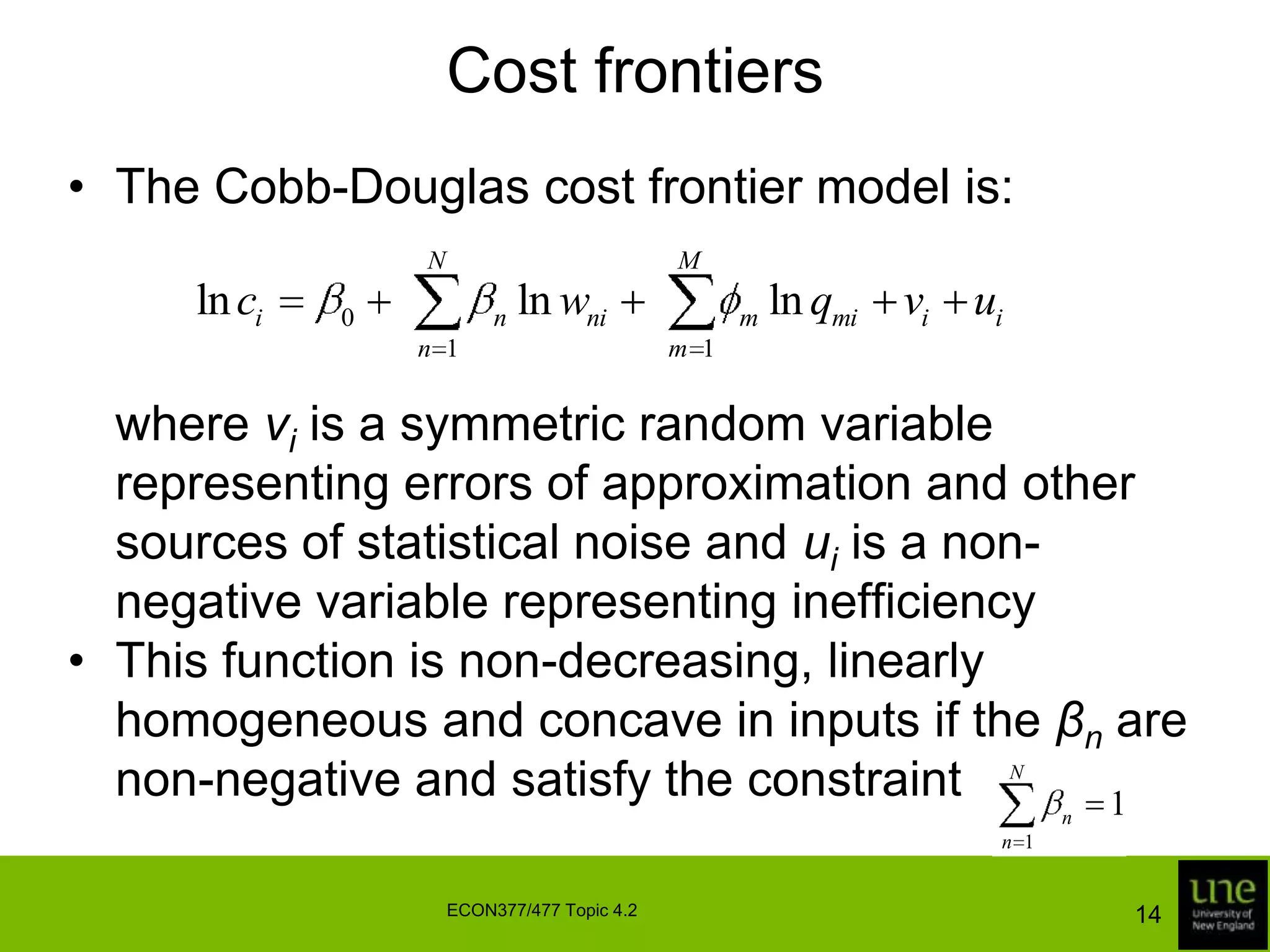

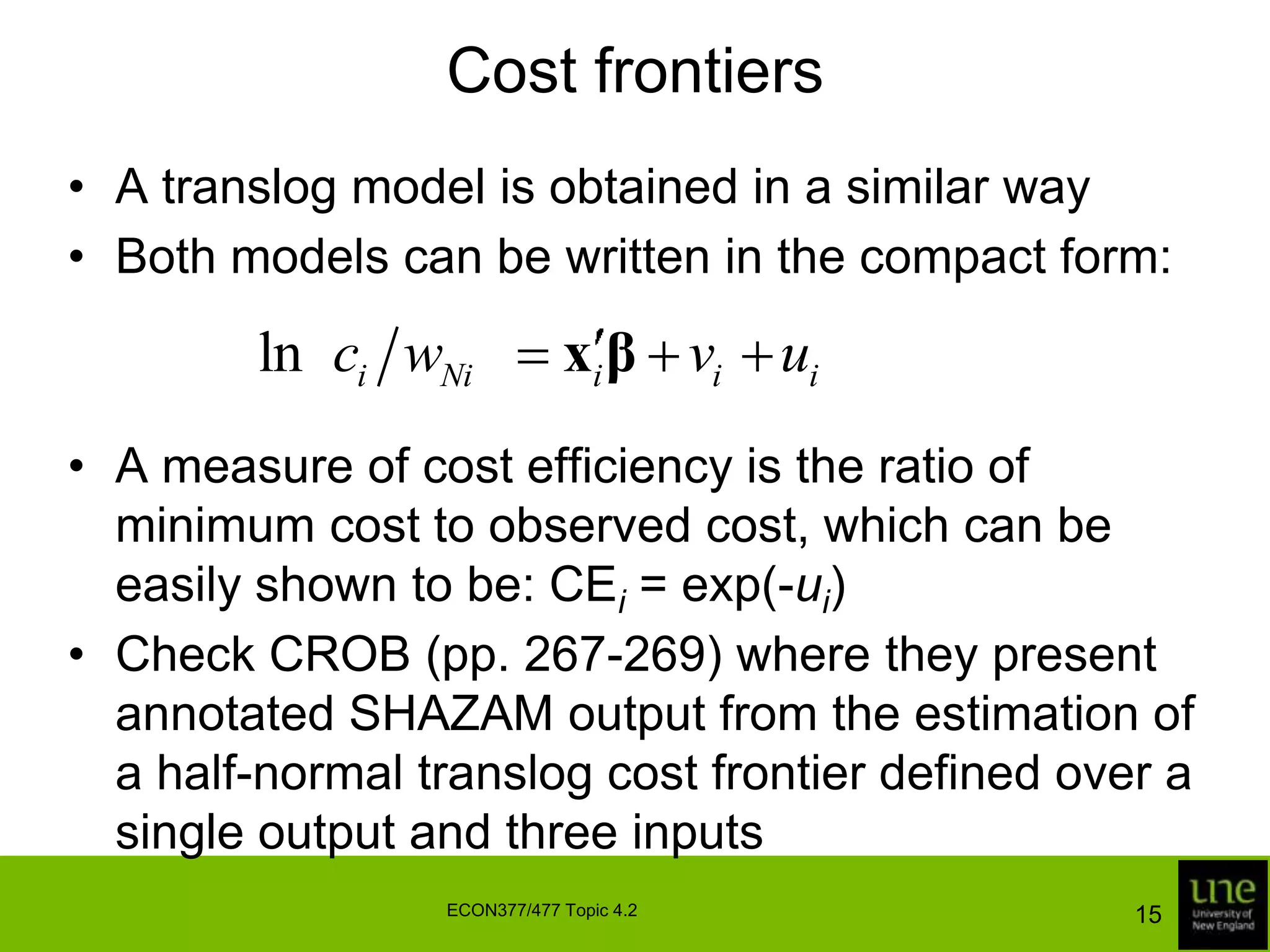

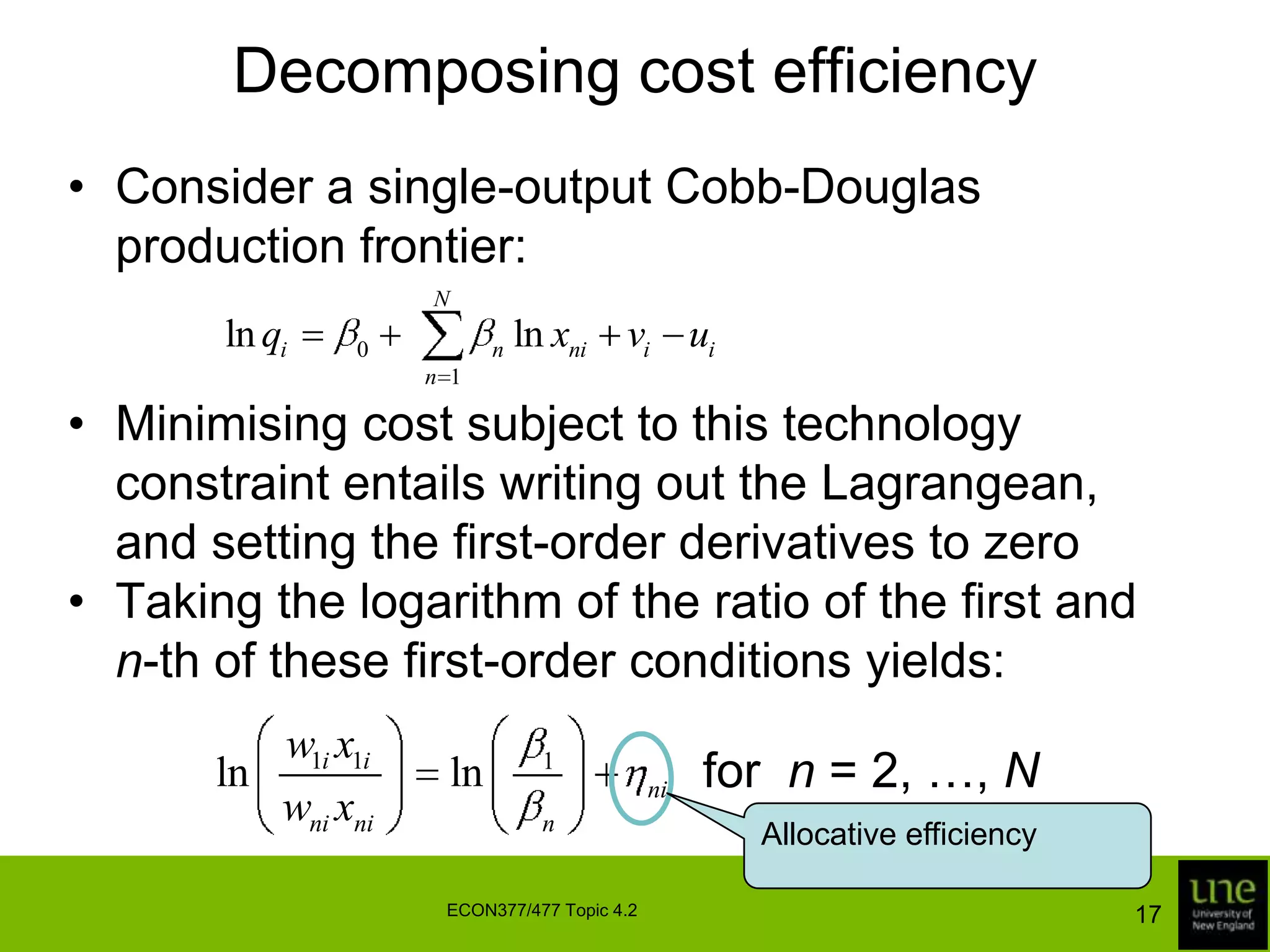

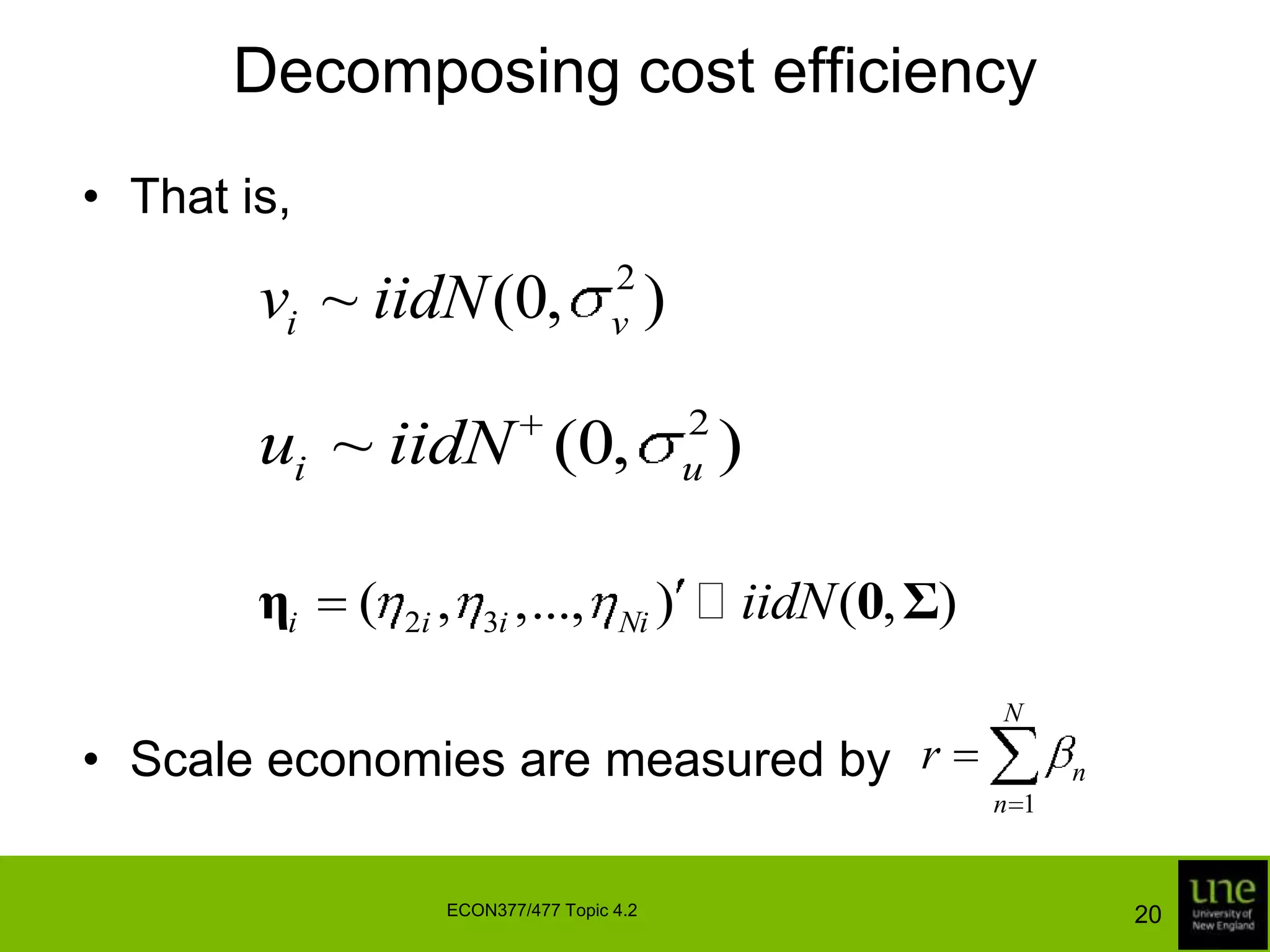

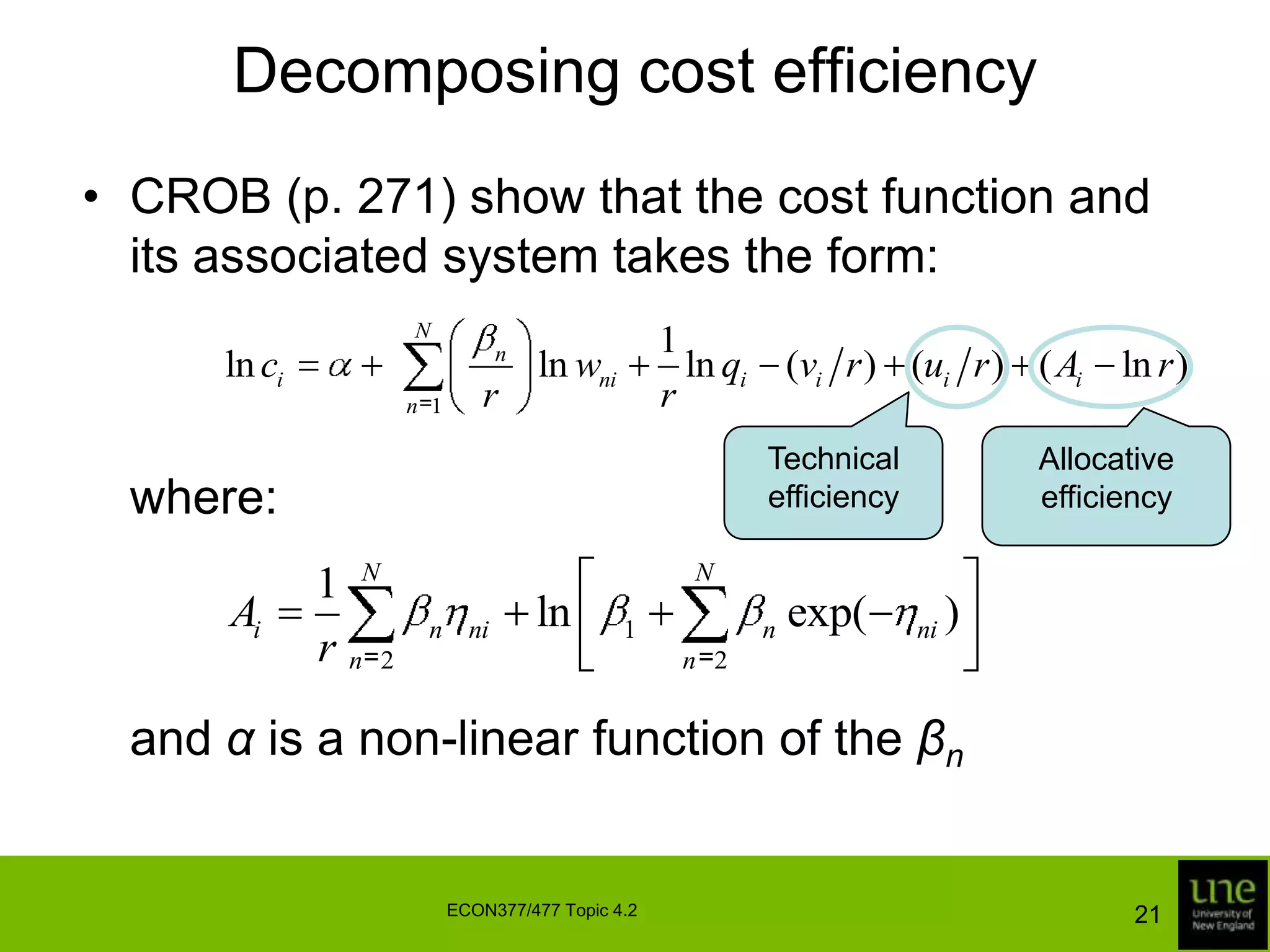

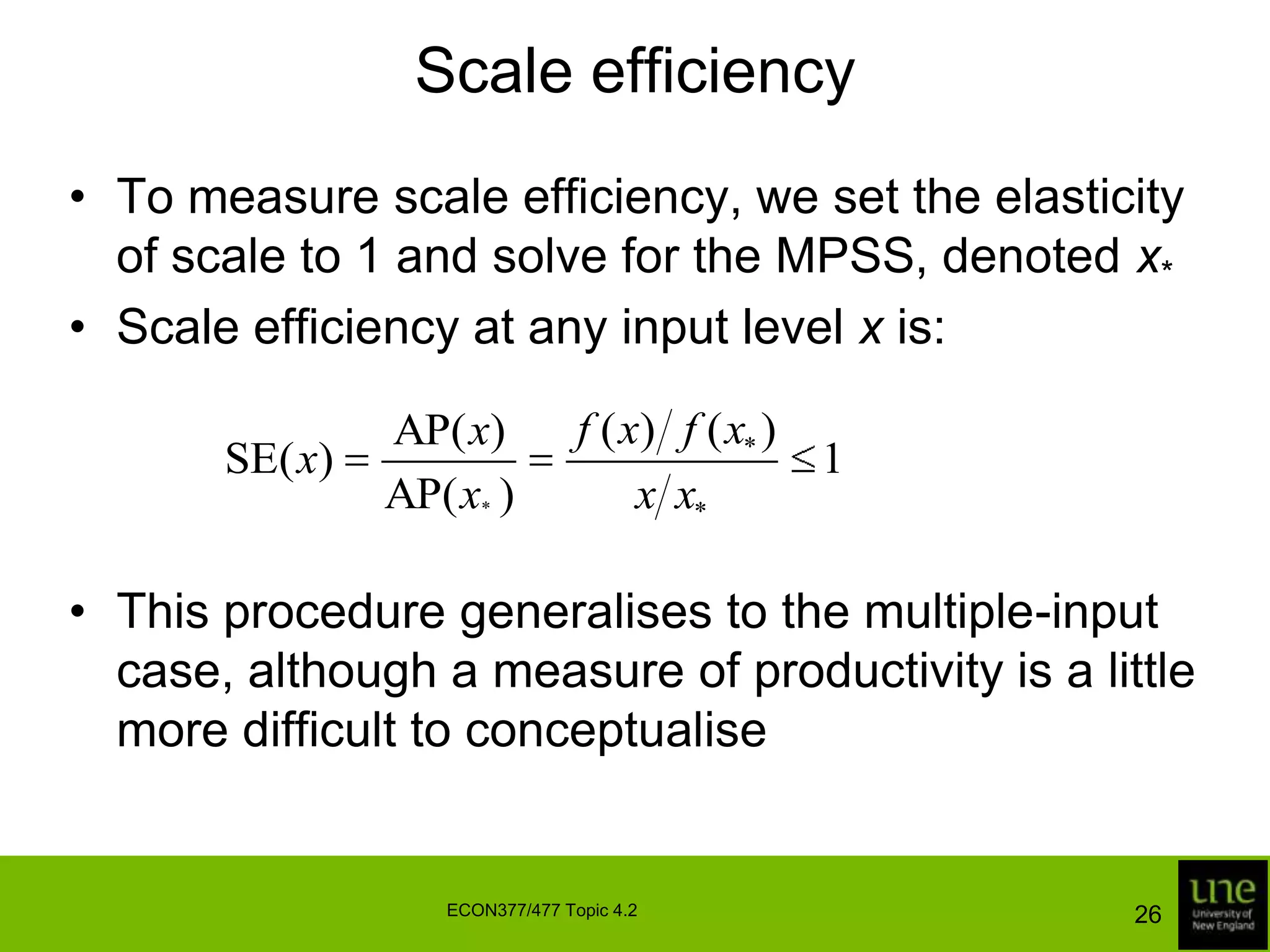

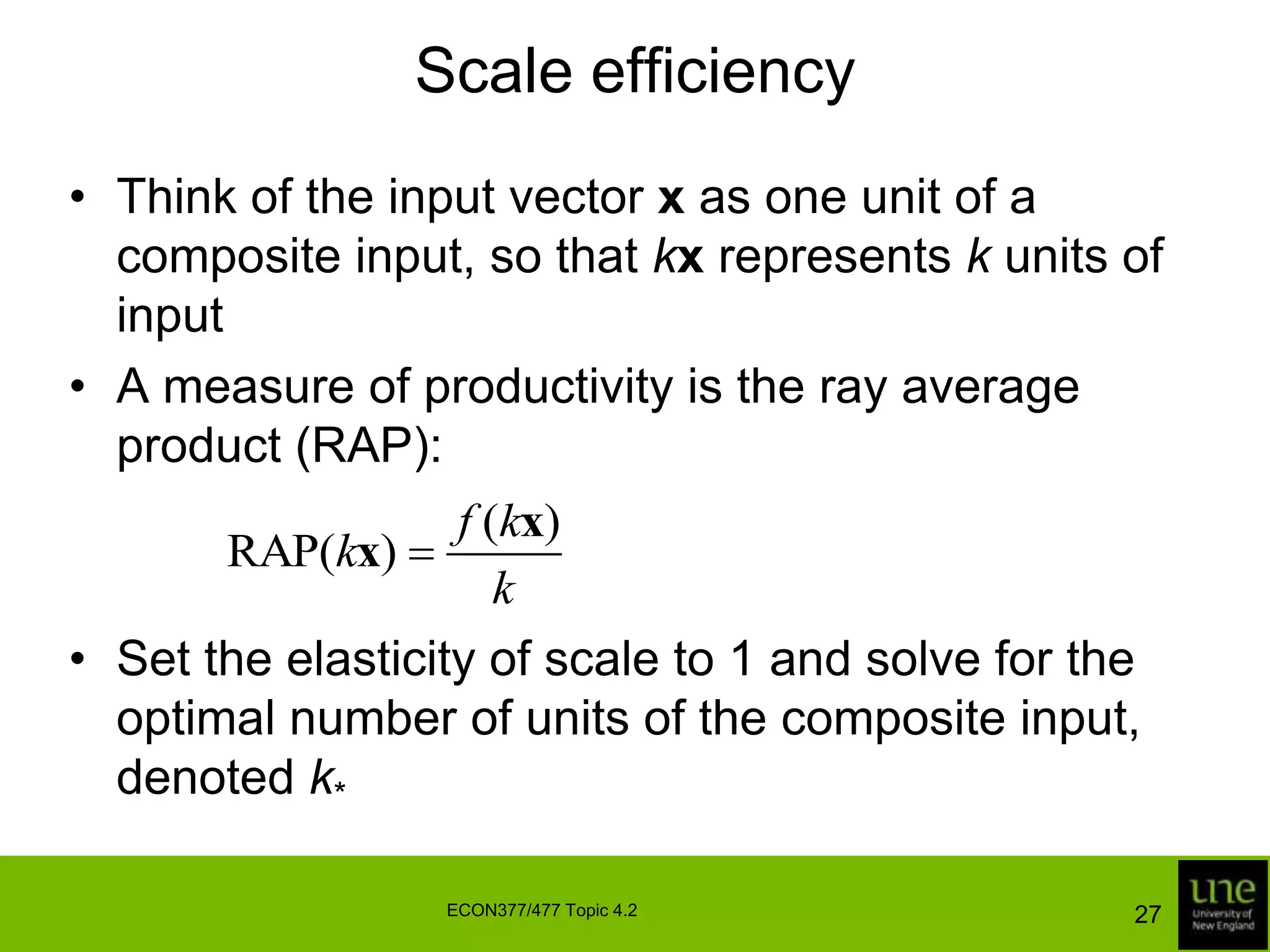

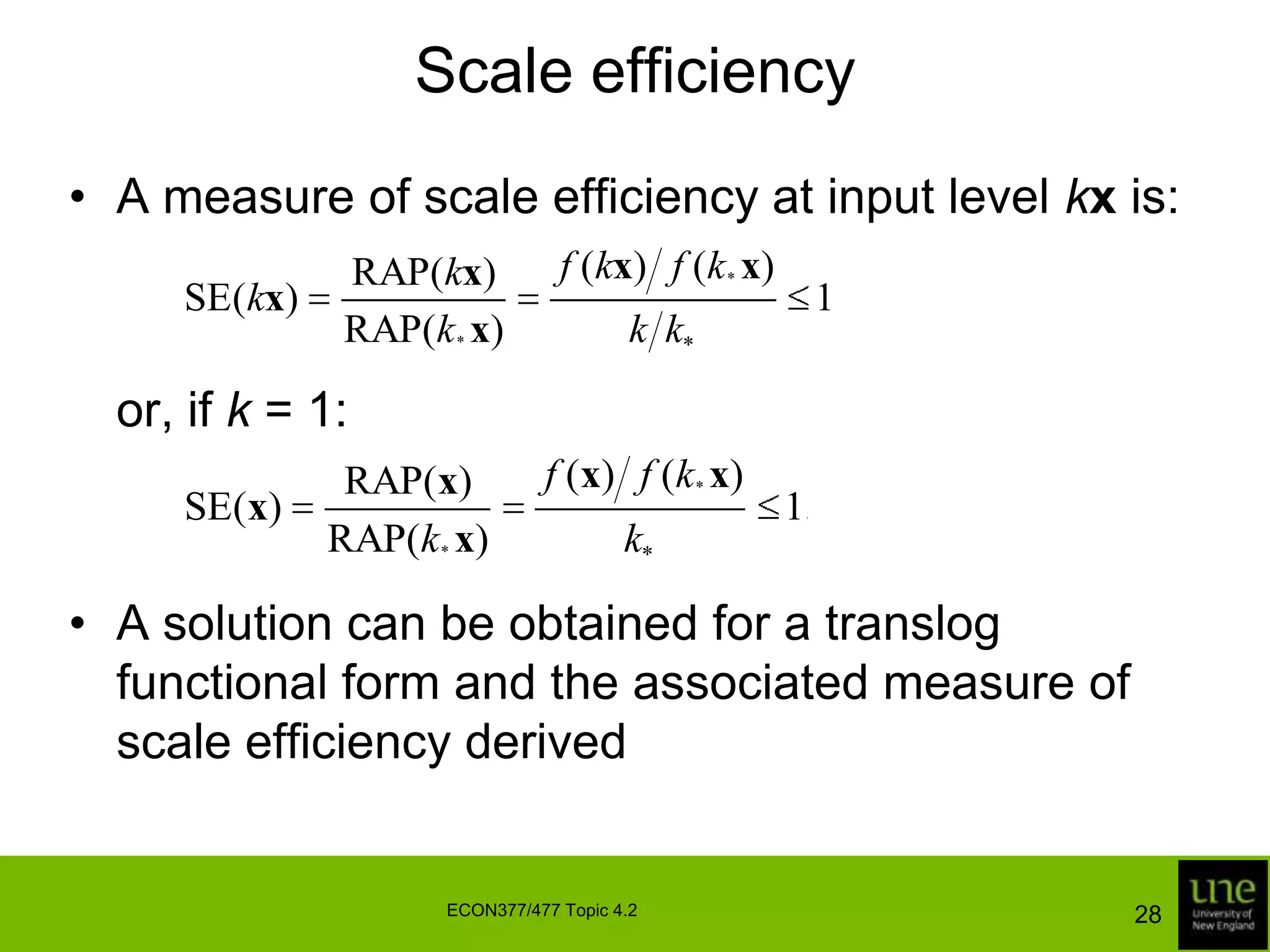

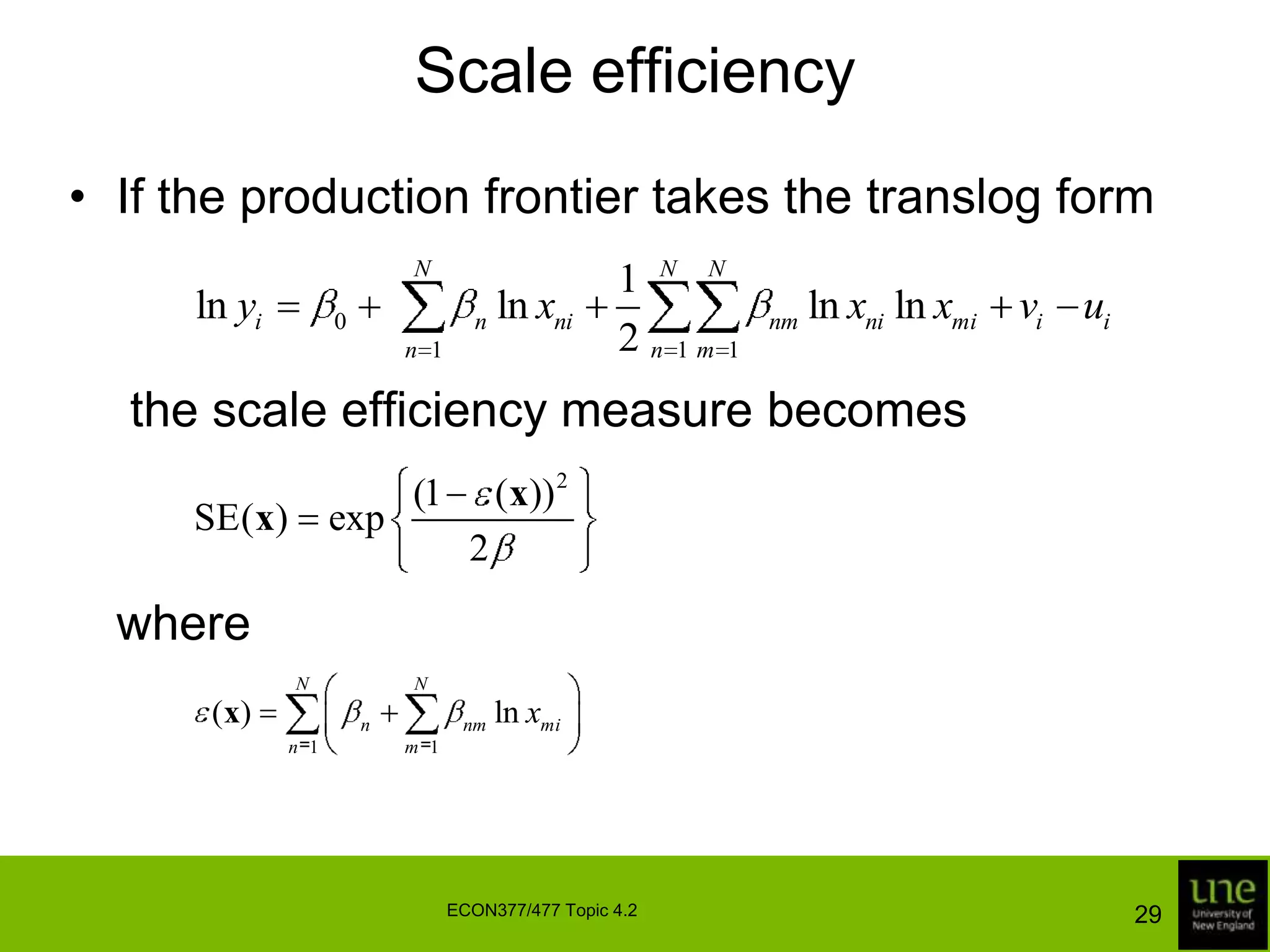

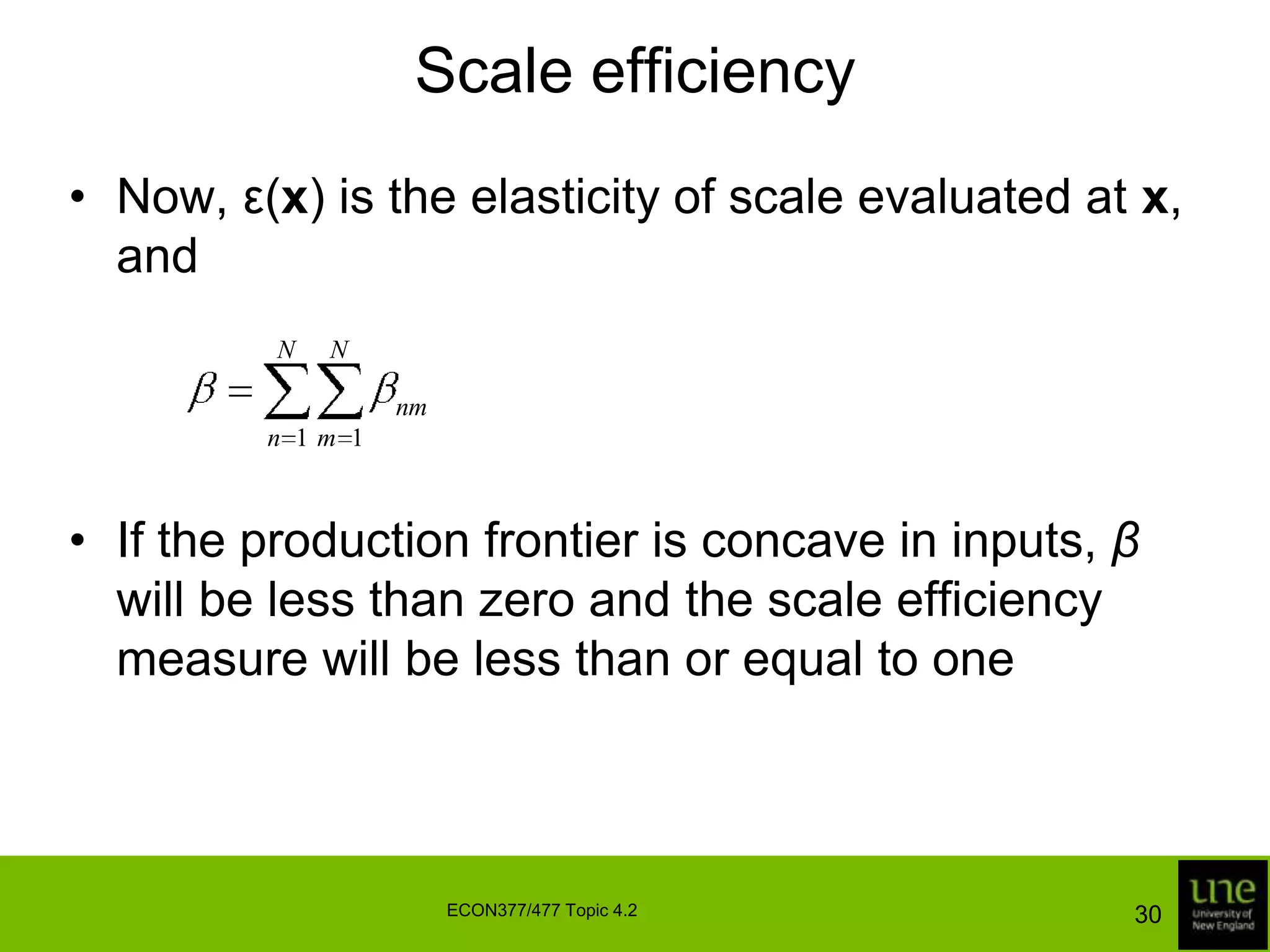

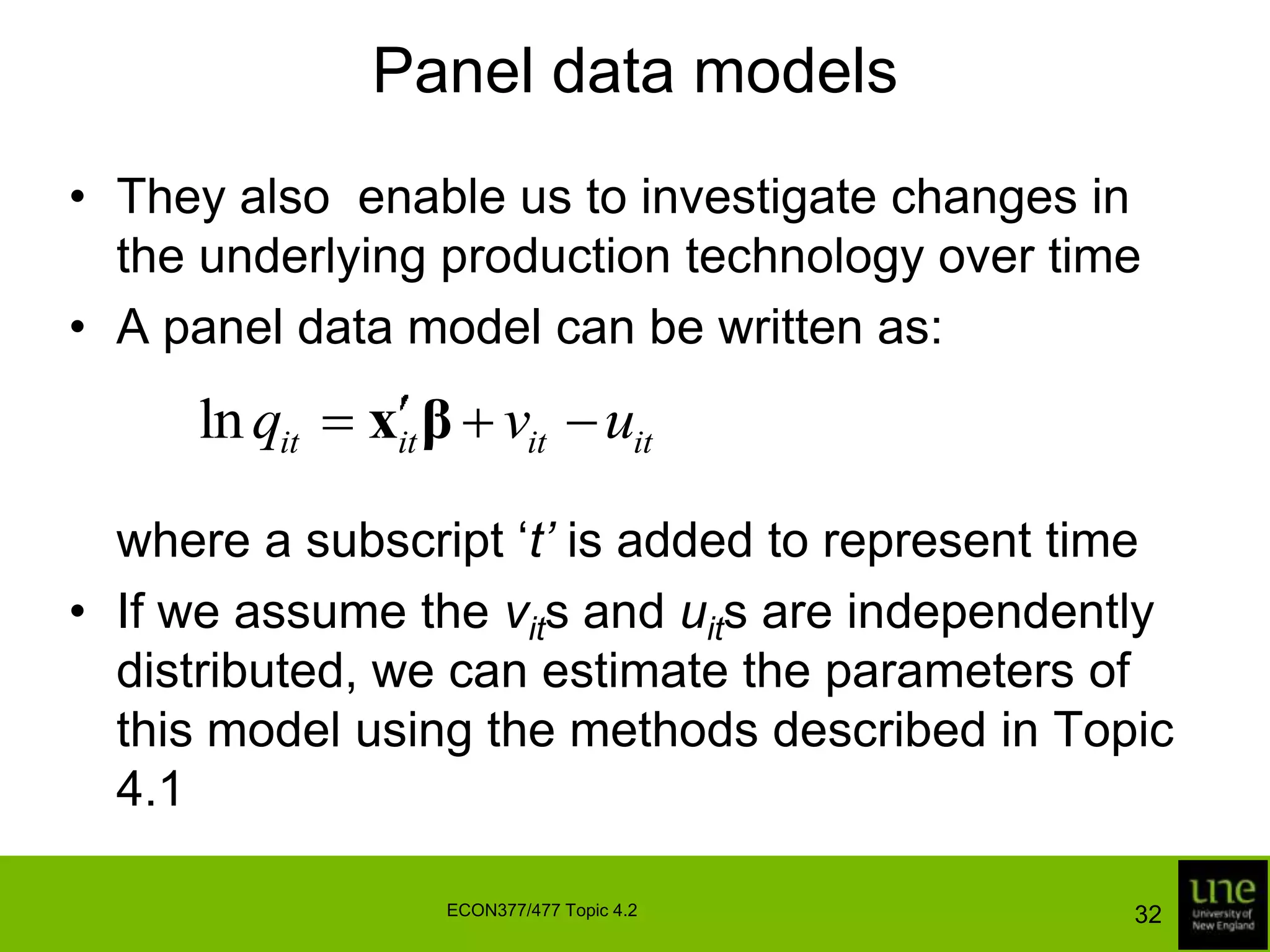

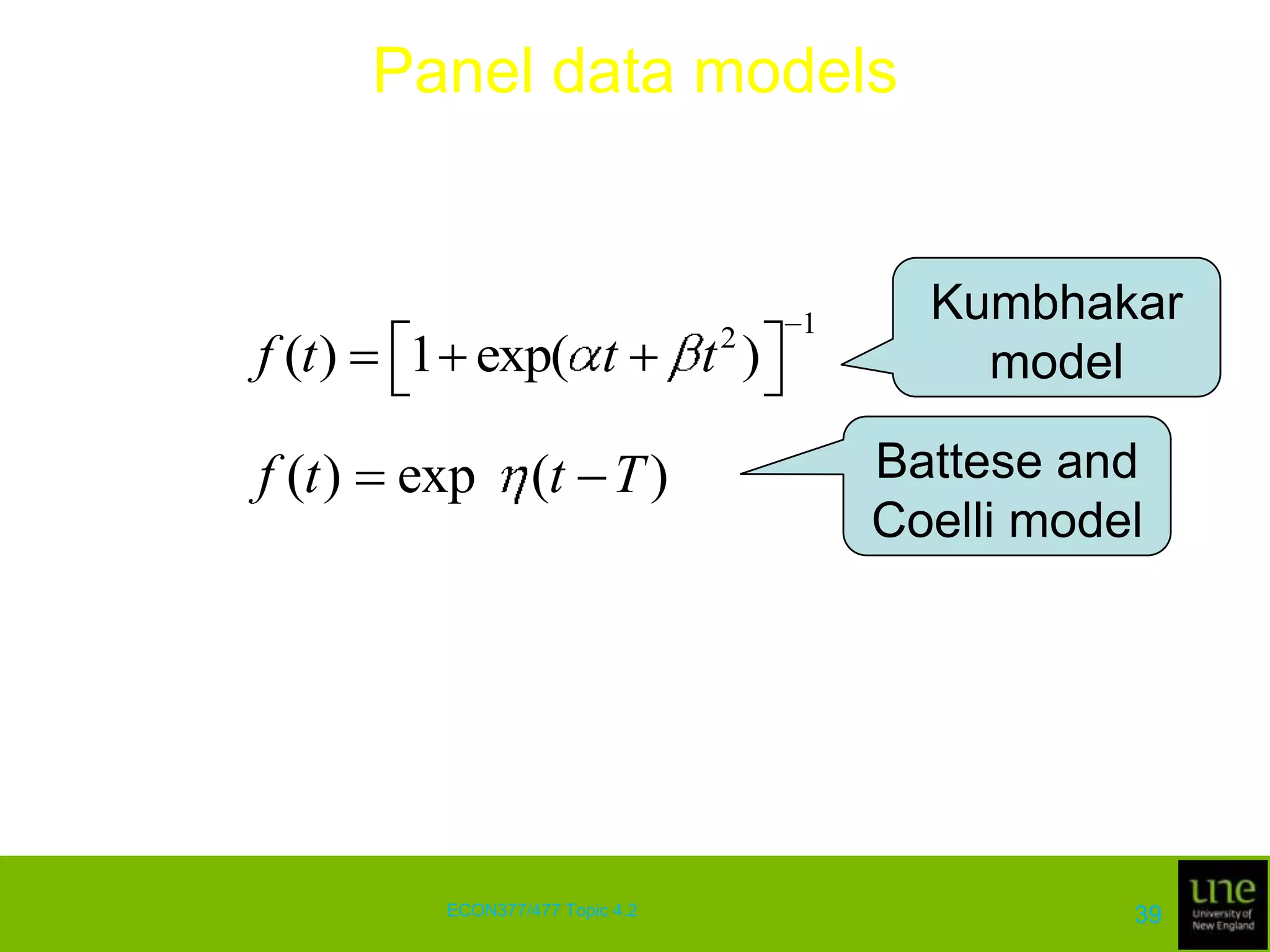

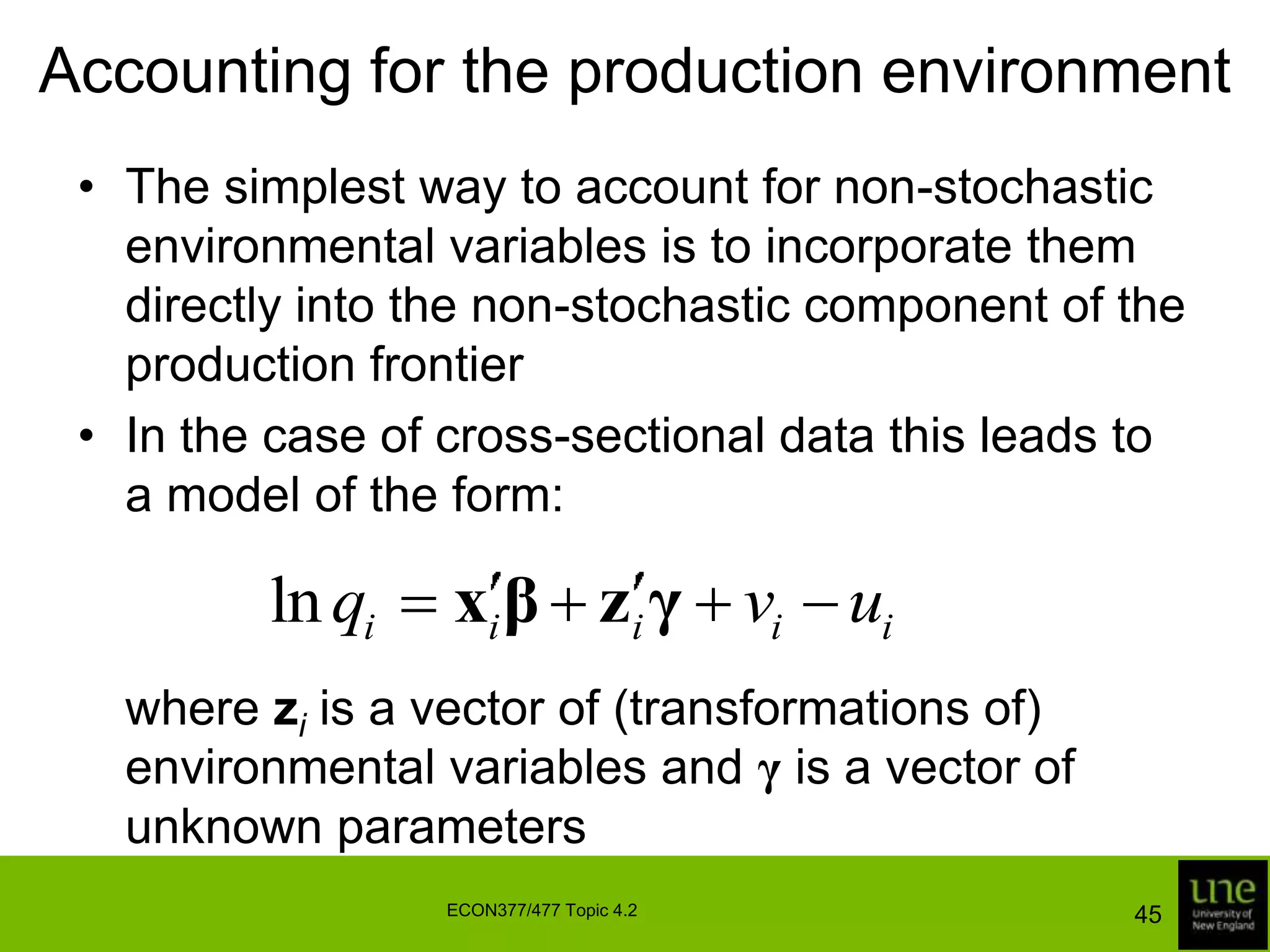

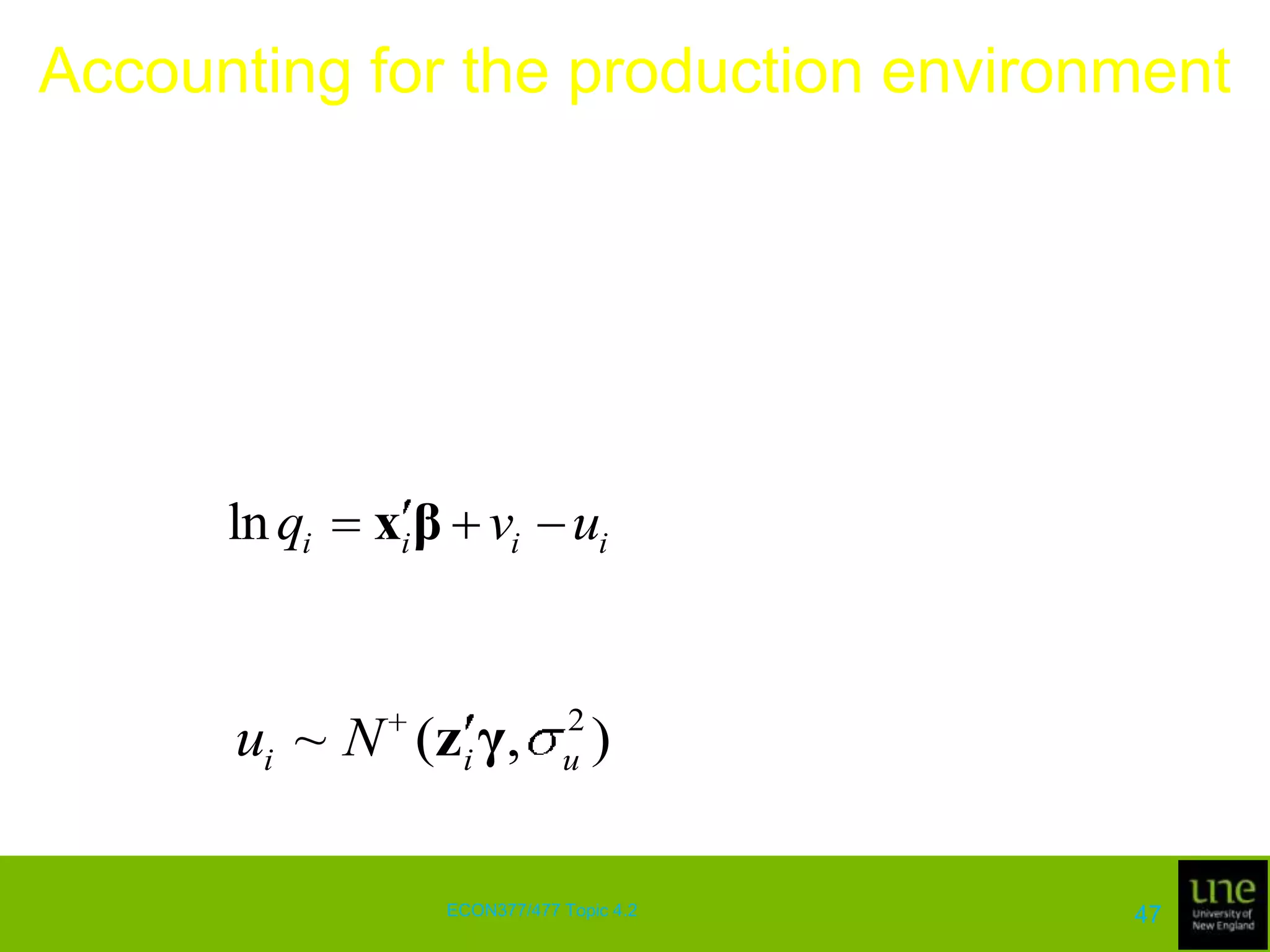

This document discusses stochastic frontier analysis and techniques for estimating production frontiers and cost frontiers using cross-sectional and panel data. It covers distance functions, cost frontiers, decomposing cost efficiency into technical and allocative components, measuring scale efficiency, and accounting for the production environment in panel data models.