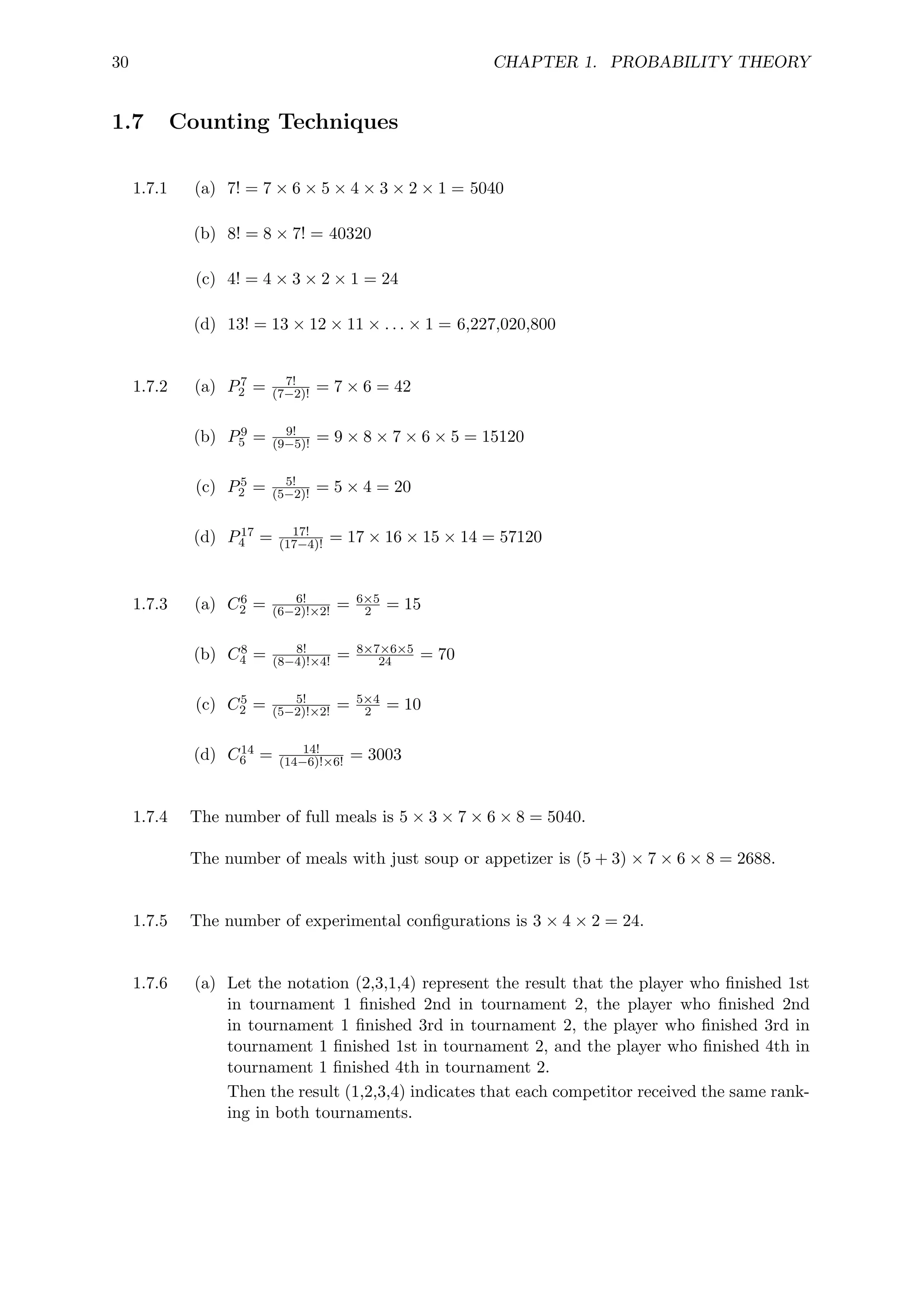

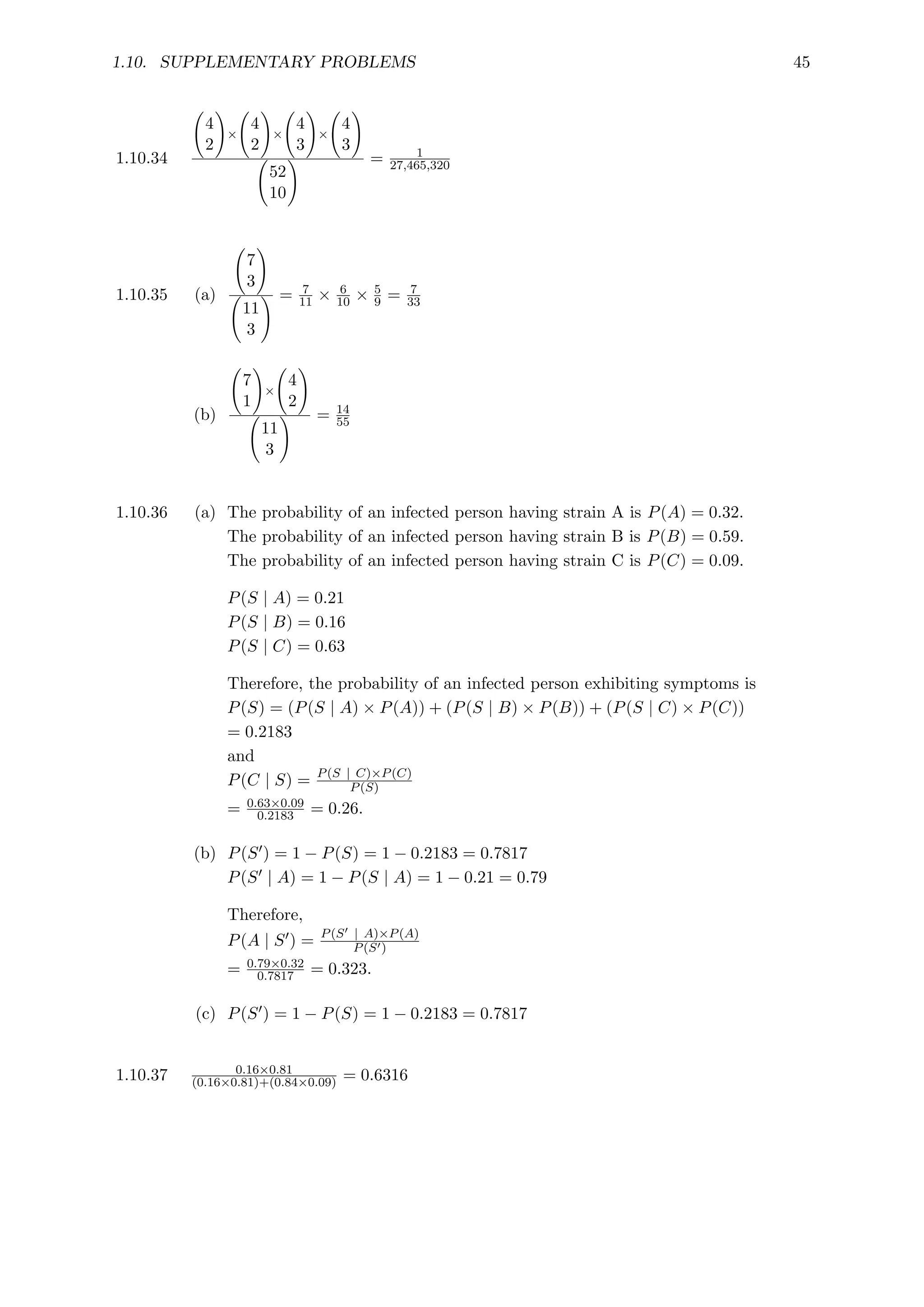

The instructor solution manual for 'Probability and Statistics for Engineers and Scientists' (4th edition) by Anthony Hayter offers comprehensive worked solutions to nearly all textbook problems, including even-numbered and supplementary problems. It complements the student solution manual, which includes answers to only the odd-numbered problems. The manual covers various topics, such as probability theory, random variables, probability distributions, descriptive statistics, and statistical estimation.