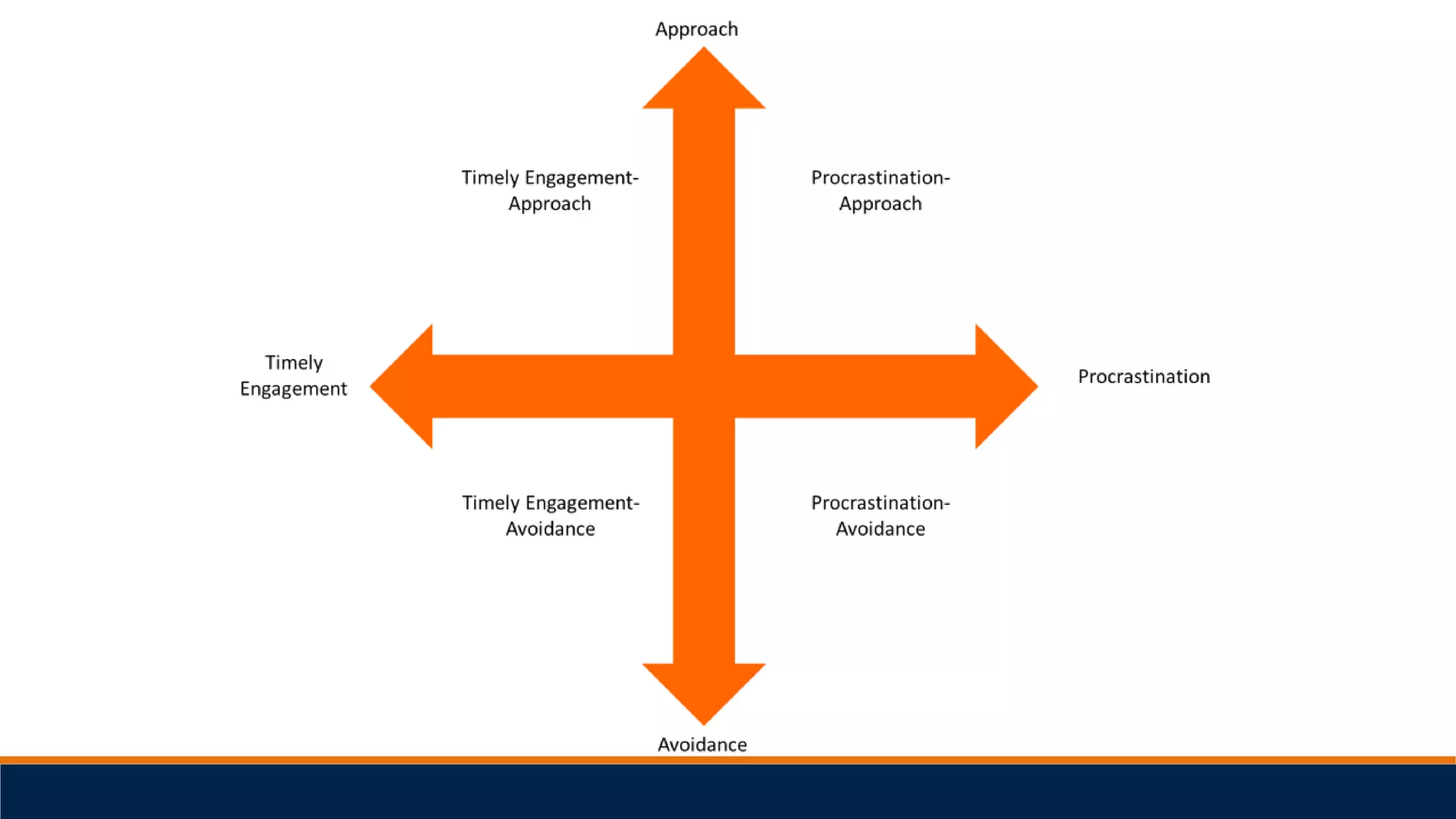

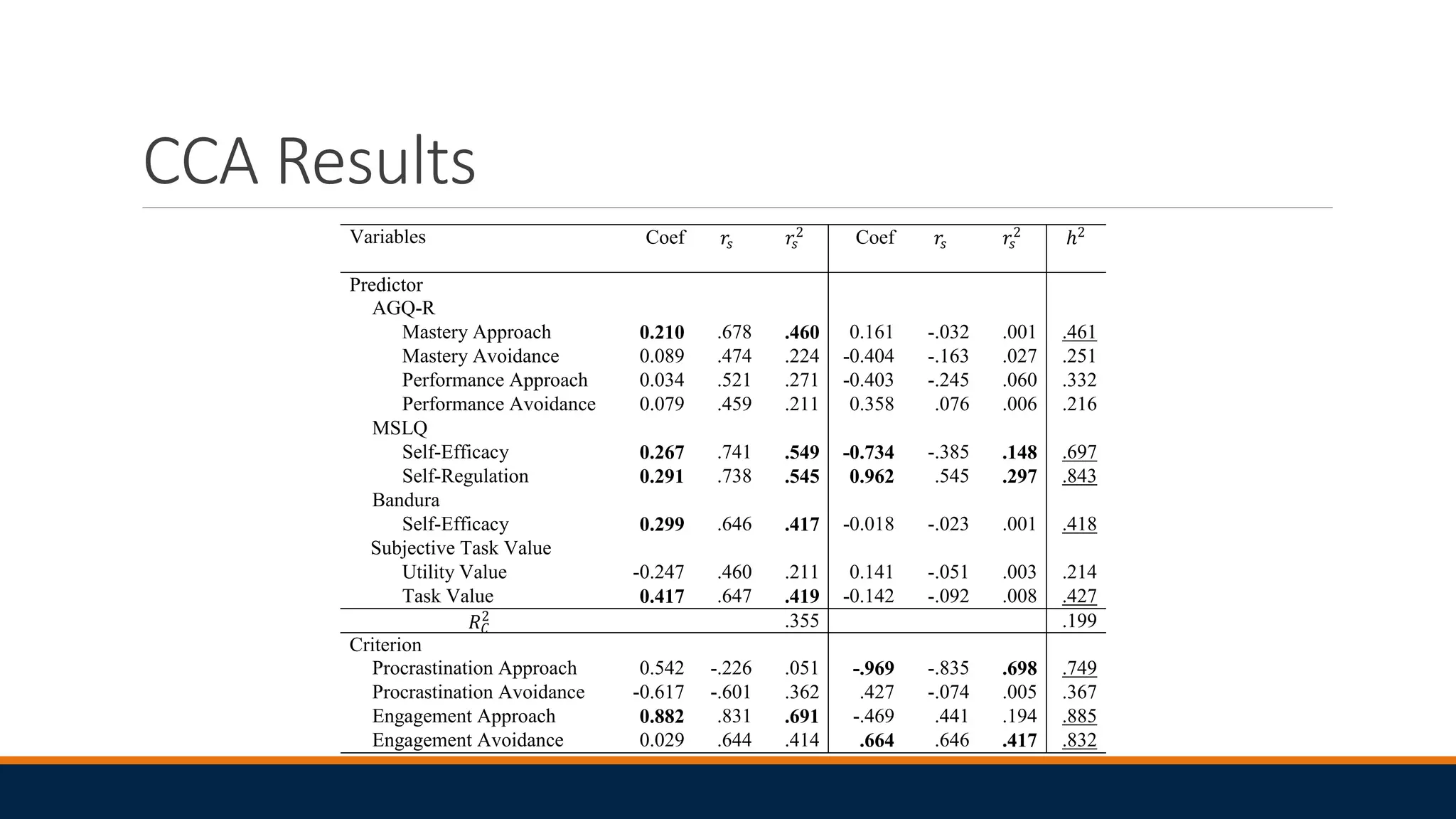

This study examined whether time-related academic behavior is stable or context-dependent. Researchers analyzed data from over 450 undergraduate students who completed surveys in a fall semester and spring semester. They identified four clusters of time-related behavior: generalized timely engagement, timely engagement/approach, generalized procrastination, and timely engagement/avoidance. Most students (51%) changed clusters between semesters, indicating behavior is context-dependent. Motivation factors like self-efficacy, goal orientation, and self-regulation predicted changes in behavior, particularly increases in adaptive timely engagement and decreases in maladaptive procrastination avoidance. This suggests motivation can influence academic behavior and existing intervention strategies may help students adopt more productive habits.