This document discusses several theories of stock market fluctuations:

1) The efficient market hypothesis which states prices reflect all known information and movements are due to new information.

2) The random walk hypothesis which claims fluctuations are totally random and unpredictable.

3) Behavioral economics perspectives which emphasize the role of human psychology in driving mass movements.

It also examines the work of Fama on market efficiency forms, Malkiel's refutation of fundamental and technical analysis, and Taleb's criticisms of attempts to explain movements with structured models. The document aims to statistically test and potentially refute these theories of market predictability.

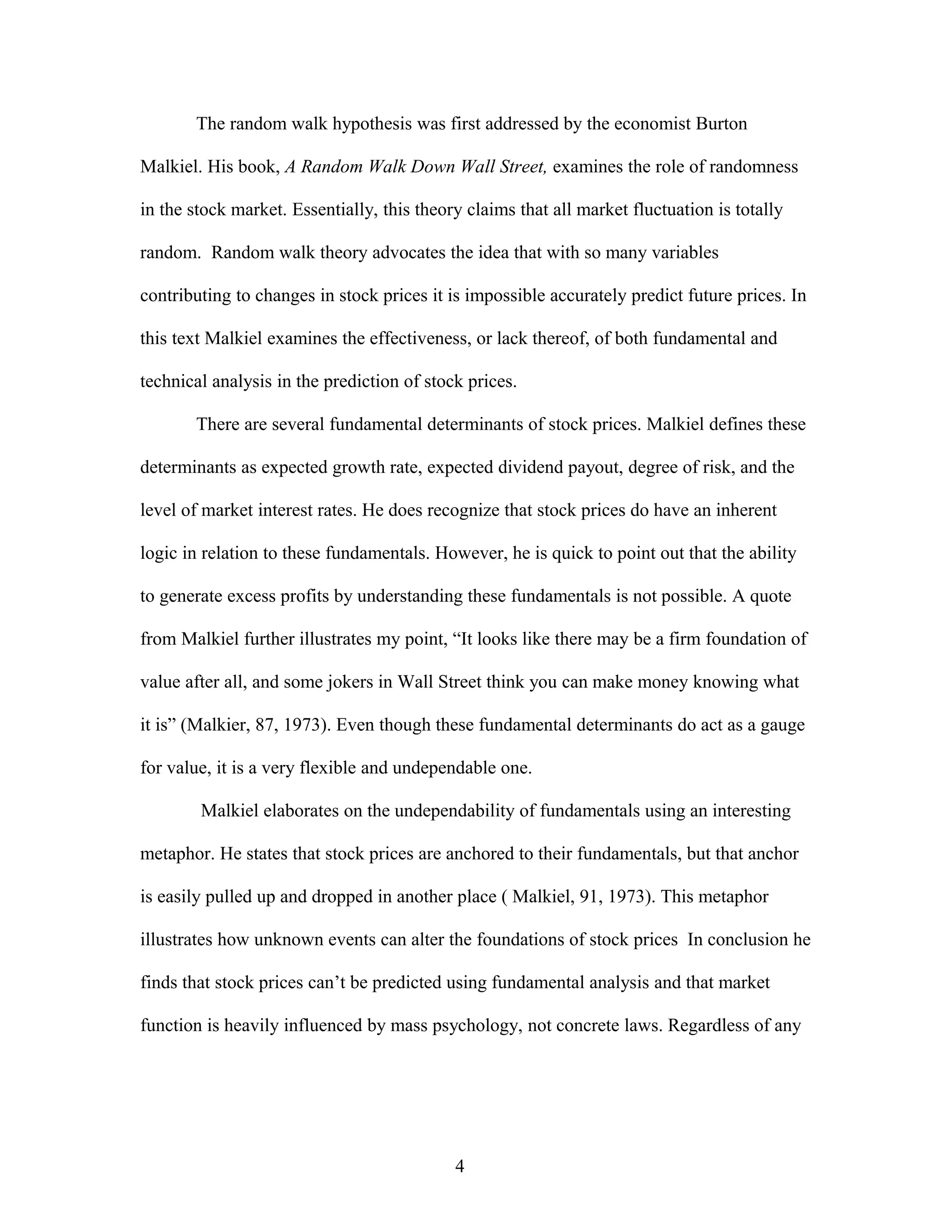

![3 1.1068585E11 3.6895284E10 8061852.2560413 <.0001

7016 32108913.1018989 4576.5269530

7019 1.1071796E11

DF Sum of Squares Mean Square F-Value P-Value

Regression

Residual

Total

ANOVA Table

Price vs. 3 Independents

7020

4

.9998550

.9997100

.9997099

67.6500329

Count

Num. Missing

R

R Squared

Adjusted R Squared

RMS Residual

Regression Summary

Price vs. 3 Independents

1.5625101 1.3646751 1.5625101 1.1449686 .2523

1.0000201 .0002038 .9997947 4906.6283393 <.0001

.0126629 .0030698 .0016132 4.1250226 <.0001

-41.1891952 20.6173606 -.0007807 -1.9977919 .0458

Coefficient Std. Error Std. Coeff. t-Value P-Value

Intercept

Pricet-1

BlackPast

BlackL1

Regression Coefficients

Price vs. 3 Independents

3468

3552

64002230.911805

1.993286

.003081

# >= 0

# < 0

SS[e(i) - e(i-1)]

Durbin-Watson

Serial Autocorrelation

Residual Statistics

Price vs. 3 Independents

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/516d36ca-3908-4361-bcb0-ae44158f820a-160313014736/75/thesisdone-12-2048.jpg)