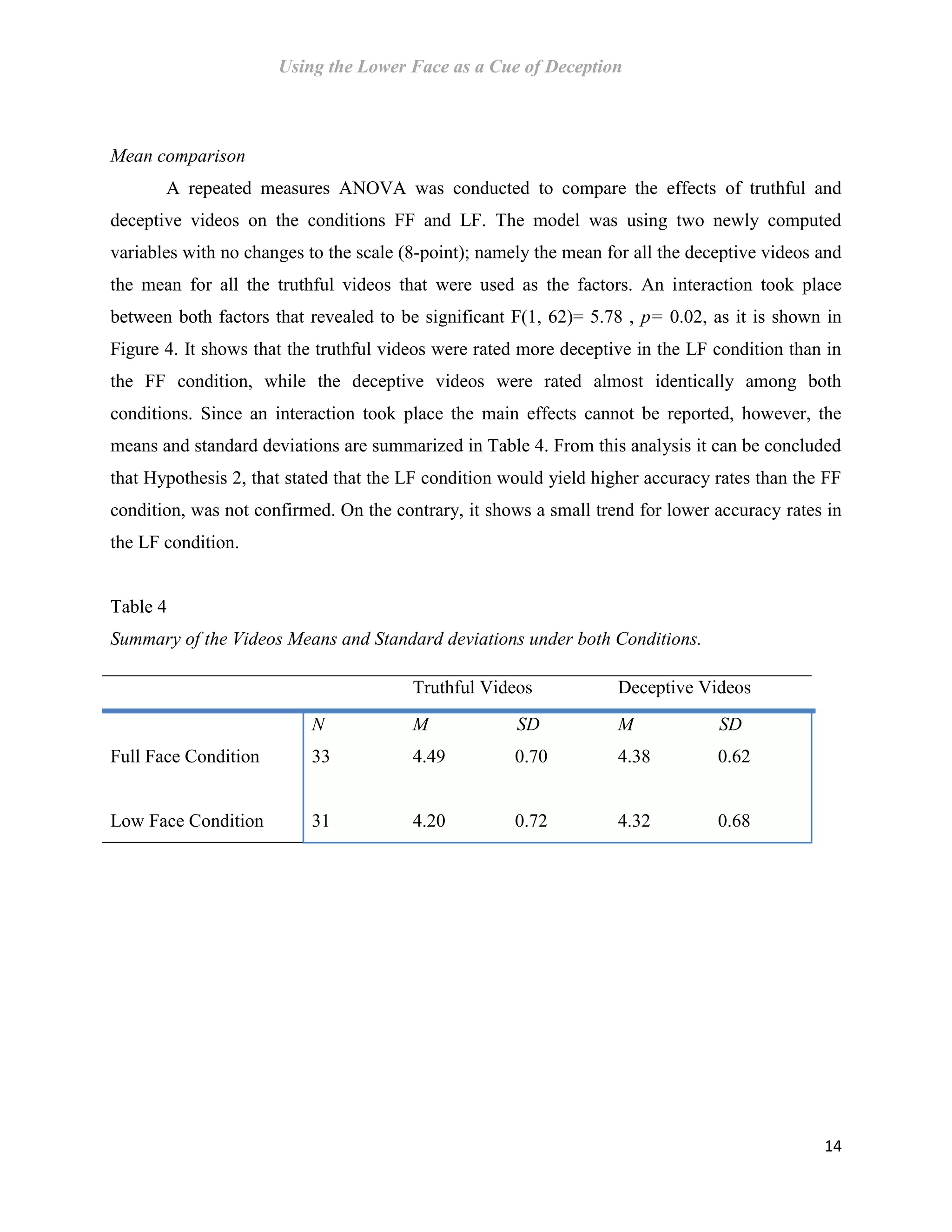

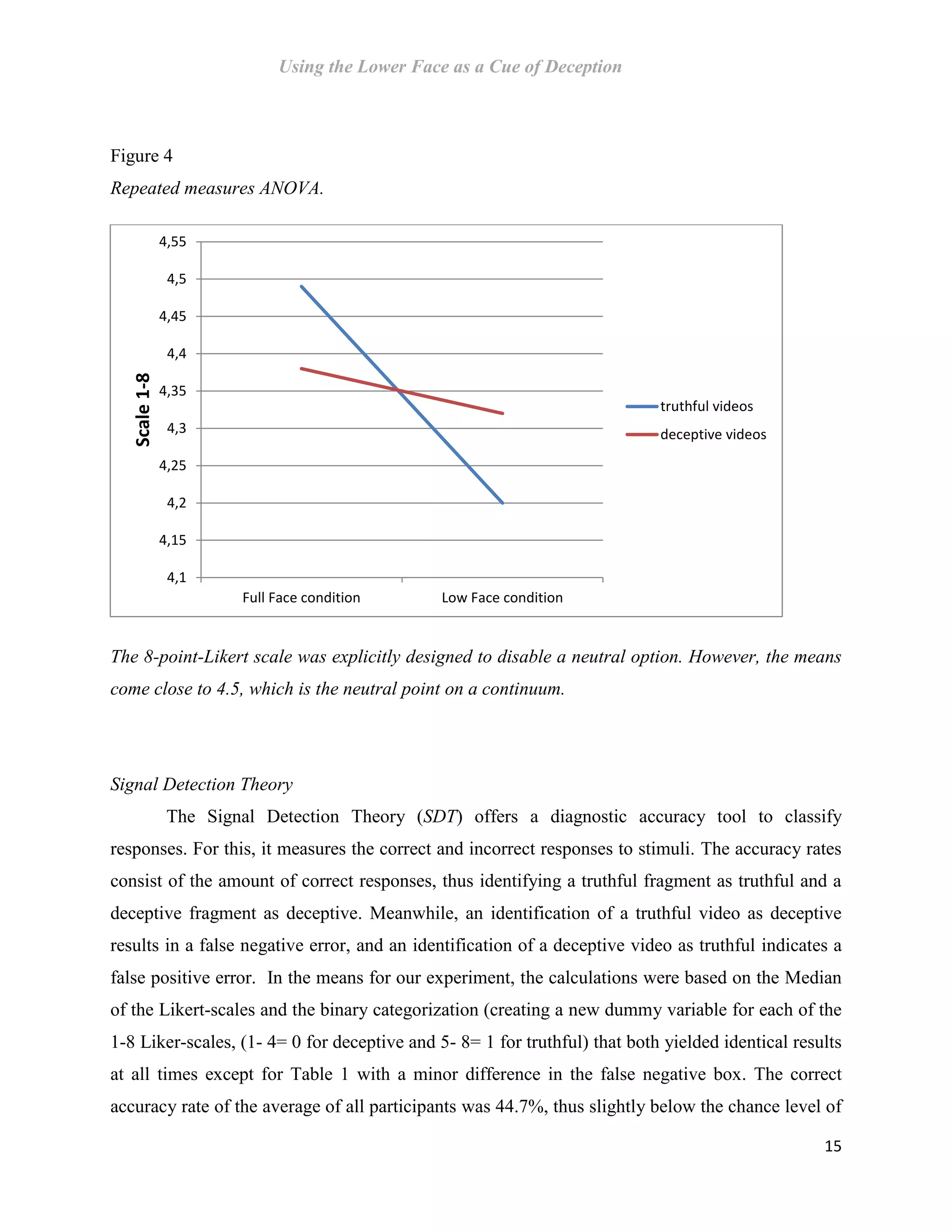

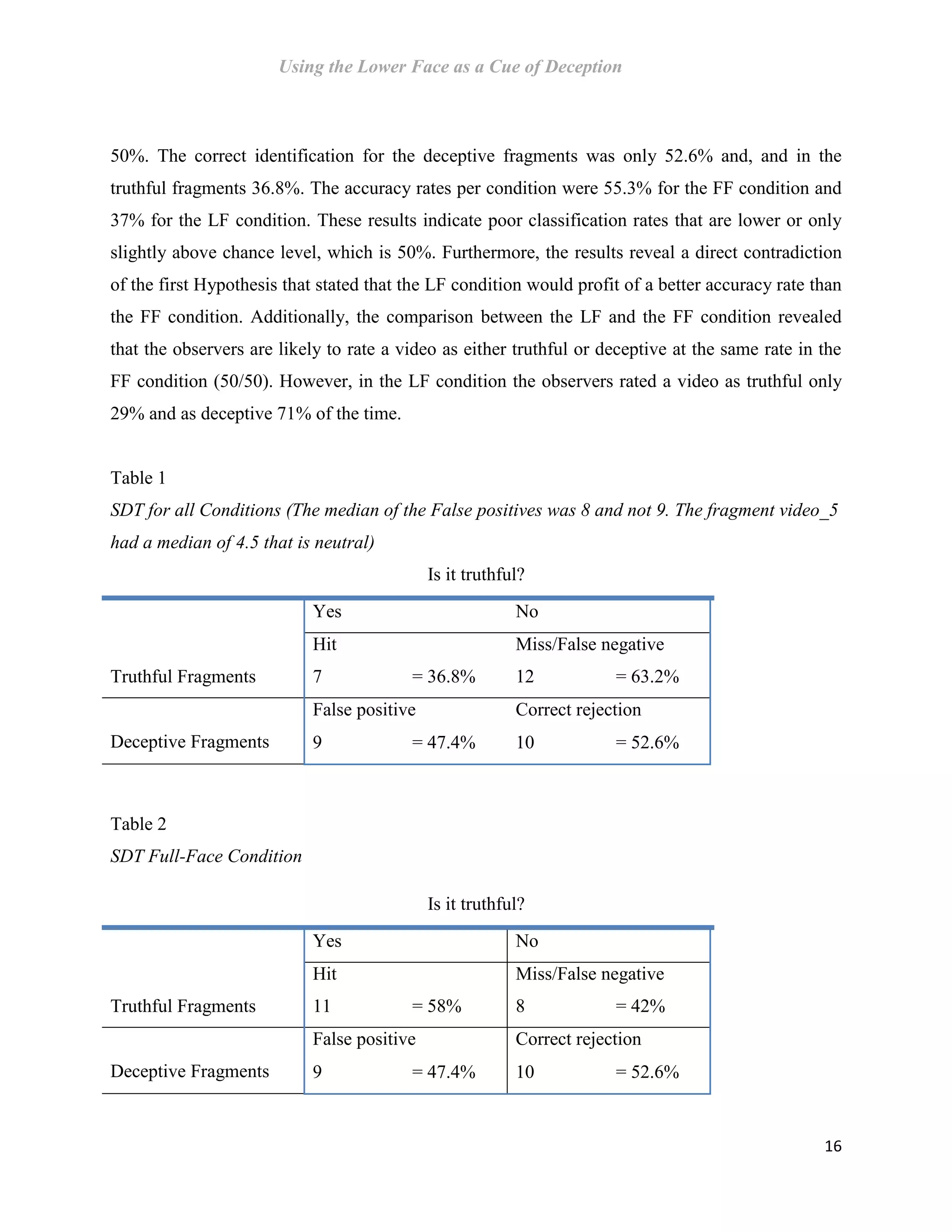

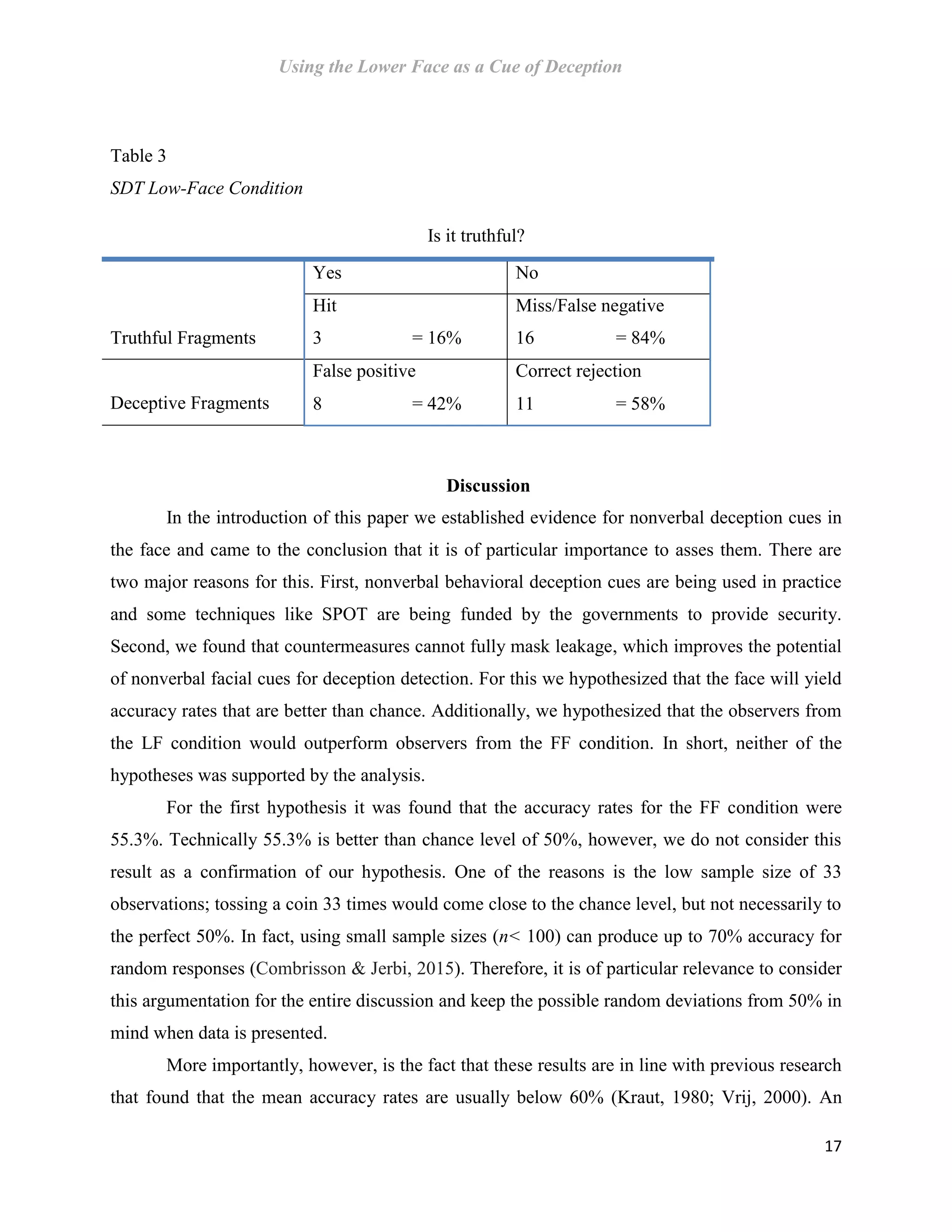

This document is a master's thesis that investigates the use of the lower face as a cue for deception detection. Specifically, it examines the US airport security program called SPOT that claims to use behavioral detection techniques to identify terrorists and criminals based on nonverbal cues like facial expressions. The thesis conducted an experiment comparing accuracy rates of observers who viewed videos showing only the lower face versus the full face. Contrary to hypotheses, results showed higher accuracy for full face (55.3%) than lower face (37%) videos, disconfirming the lower face as a reliable deception cue. The thesis also critically reviews the scientific evidence for techniques used in SPOT, finding little support for many cues on its checklist and the ability to accurately detect