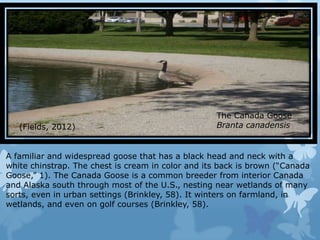

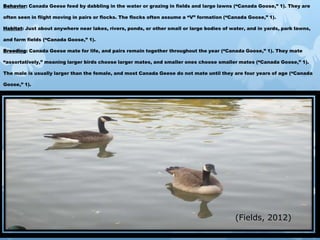

The student conducted a research project studying three species of waterfowl - Canada geese, mallards, and a mallard hybrid - at a lake located in York city. Over several weeks, the student observed and took photos to document each species' behavior, habitat use, and interactions with the urban environment. The report provides details on the identifying characteristics, behaviors, breeding, and habitat of Canada geese and mallards. It also discusses how mallards frequently hybridize with other species, and the challenges this can pose for waterfowl conservation.