This document summarizes a study on the use of social media in the recruitment process. It finds that over half of UK jobseekers now use social media sites like Facebook and LinkedIn to search for jobs. While social media offers opportunities to efficiently target candidates, there are also risks around privacy, discrimination, and bias. Employers need to consider how to handle personal information found online and avoid letting non-job related factors influence hiring decisions. The study examines the costs and benefits of using social media, common tools and practices, and risks to both employers and candidates. It aims to understand how social media is changing recruitment and provide advice on related legal and policy issues.

!["In fact we have very little corporate social media activity … We are a

services business, we are a people business, our product is people … With

regards to our B2C [business to consumer] offering, the only real

consumer offering we have is jobs and a lot of them - we recruit around

250,000 per year."

Head of resourcing, G4S

3.4 Different tools and ways of using social media for initial

candidate search

Social media is a broad category, encompassing practices such as podcasting,

blogging, text messaging, internet videos, and HR e-mail marketing, which are

some of the more widespread applications used in recruitment (Joos, 2008). In

addition to these tools, there are a small number of highly popular sites which

employers are using increasingly such as Facebook, Wikipedia and Yahoo. These

incorporate tools to attract the attention of potential candidates typically ranging

from websites to blogs, wikis, podcasts and video platforms. For an overview of

the main social media tools, see Box 2 in section 2.2 above.

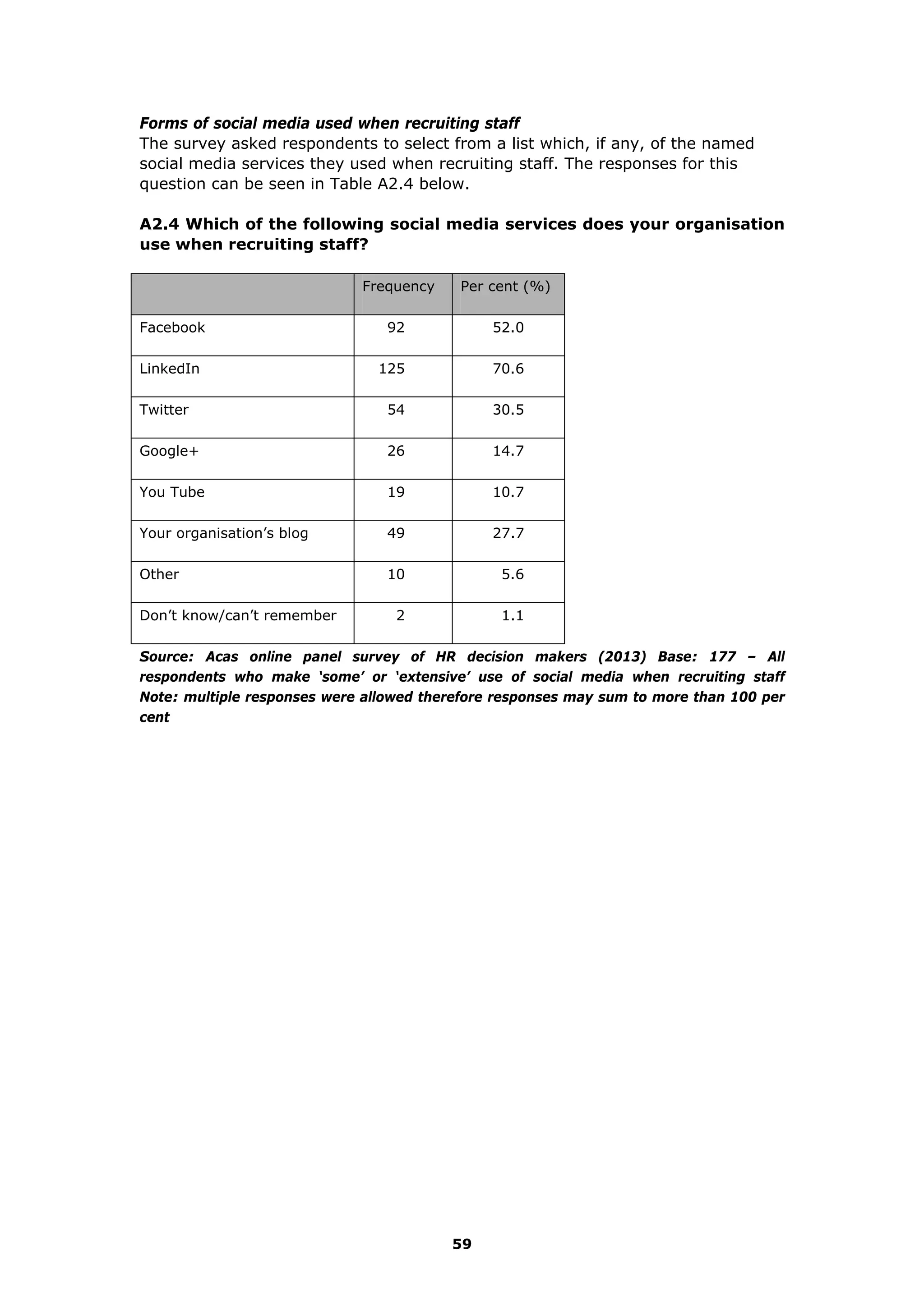

A recent study by Jobvite (2012) among employers reveals that globally, LinkedIn

is currently the most popular social network tool being used for recruiting (used

by 93 per cent of employers), followed by Facebook (66 per cent) and Twitter (54

per cent). Moreover, it seems that use of social media tools and their application

at different stages in the recruitment process differ, as does their application

between different employers.

“Some recruiters are using the leading social media channels simply to

search and advertise, while others are building longer-term strategies,

such as investing in permanent, interactive online talent pools.” (Clements,

2012)

Alongside the question of how companies are using social media in recruiting is

the issue of who they are targeting. As Joos (2008) highlights, there are some

groups of potential employees which might be more easily reached by online

recruitment activities than others.

“The internet lends itself well to finding and attracting college graduates,

skilled workers, managers, and executives. These groups tend to be

computer-literate, and technology use is an integral part of their daily

routines, helping them develop and maintain connections at work as well

as in their personal lives.” (Joos, 2008)

The author further specifies that the use of social media is growing particularly in

the case of graduate recruitment, with the so called ‘millennials’1

responding

extremely well to social media. This is presumably due to their familiarity with

internet tools. In addition, e-recruitment may also attract the attention of passive

1

Broadly taken to include those with birth dates from the late 1970s/early 1980s to the

late 1990s.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0fff724c-4766-432e-97aa-4d6a257eee0c-160901054011/75/The-use-of-social-media-in-the-recruitment-process-17-2048.jpg)

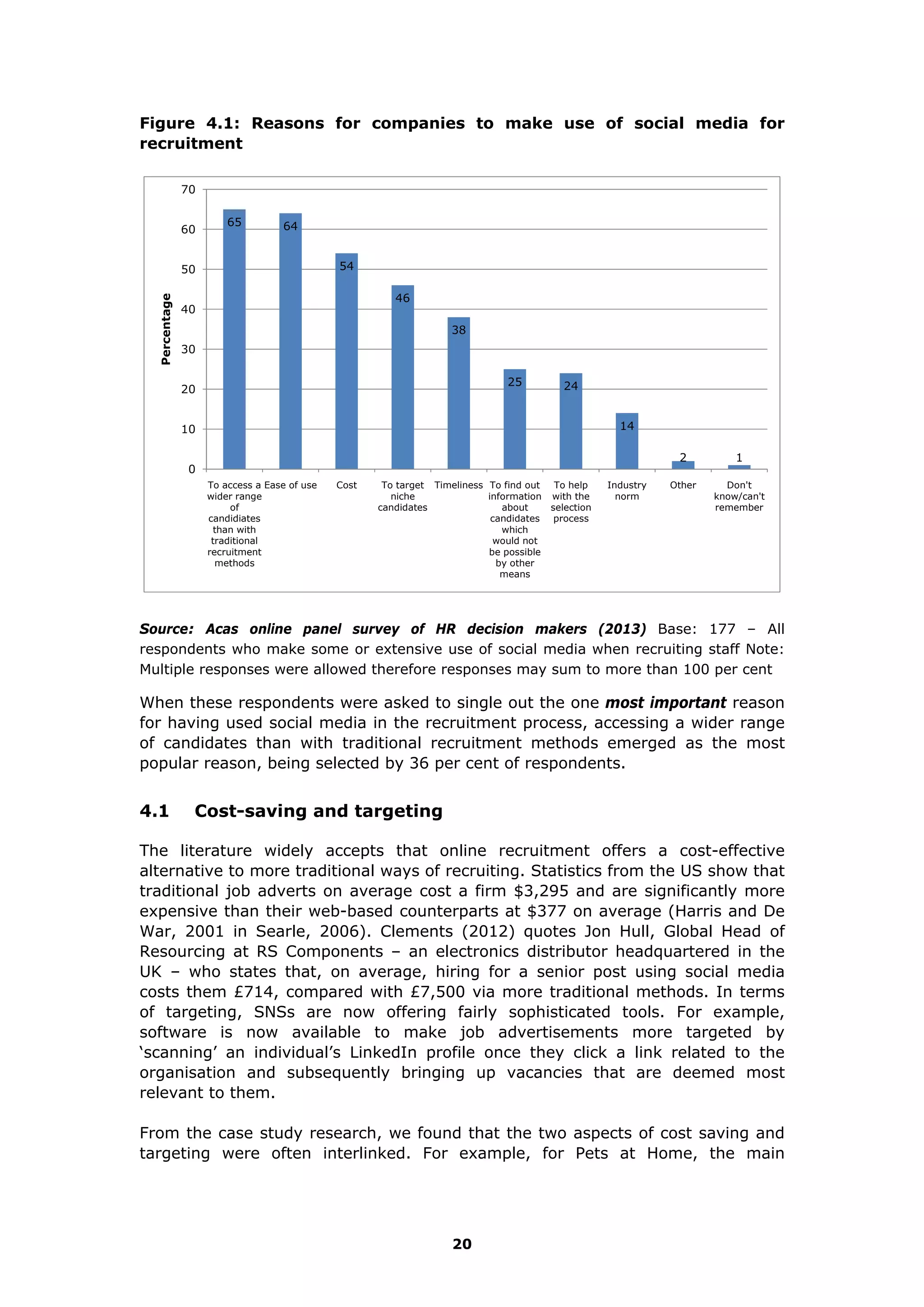

![benefits of using social media for recruitment are being able to have access to a

wider pool of people, and as a result of that, being able to reduce costs.

"Head of Internal Audit would not have been a role that we would even

have thought about recruiting ourselves a couple of years ago … This is

saving a lot of money that would have been spent on a recruitment

agency, which is what we would have done. We have access to the same

tools as recruitment agencies, so the only way that you would pay them

now is if you couldn’t be bothered to do it yourself, or if you were too

busy."

People Director, Pets at Home

This was also the case at Monmouthshire County Council, which uses social media

to reach a pool of potential candidates that is at the same time wider and more

targeted.

"For jobs where we’re looking for a wider pool of talent, someone who is a

bit different from your average candidate, the adverts will go on LinkedIn

as well as in the traditional advertising spaces. It’s so easy to advertise on

LinkedIn, and so cheap, and incredibly targeted. It’s very cost-effective.

It’s not as prestigious and won’t be seen by as many people as an advert

in the Guardian, but they will be relevant people. It’s very targeted."

Digital and Social Media Manager, Monmouthshire County Council

Social media could also be used as part of equality and diversity policies, as it

potentially allows recruiters to tap into online discussions and forums that are

engaging potential candidates in groups that they may be struggling to reach.

This strategy could be part of a general net-widening search strategy, aimed at

ensuring that organisations are not always searching in the same types of areas

for potential candidates.

4.2 Fostering realistic expectations

Interactive tools such as Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter can play an important

role in the general process around recruitment, providing recruitment information

and fostering realistic job expectations among potential employees. In a similar

vein, Searle (2006) highlights not only the importance of websites in attracting

future employees but also the fact that they can help to present realistic job

previews to candidates:

“[They] can create positive reactions to the firm (Highhouse et al., 2004).

They may also have a longer-term value by implicitly conveying the

organisation’s values and thereby promoting early organisational

socialisation. They may shape new employees’ psychological contracts”

Thus, a potential candidate can gain quite a lot of information about a potential

employer through its website and social media pages. This can help them to

decide whether they like the general feel and culture of an organisation. If not,

they can simply decide against applying, saving them and the organisation time

and money.

21](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0fff724c-4766-432e-97aa-4d6a257eee0c-160901054011/75/The-use-of-social-media-in-the-recruitment-process-26-2048.jpg)