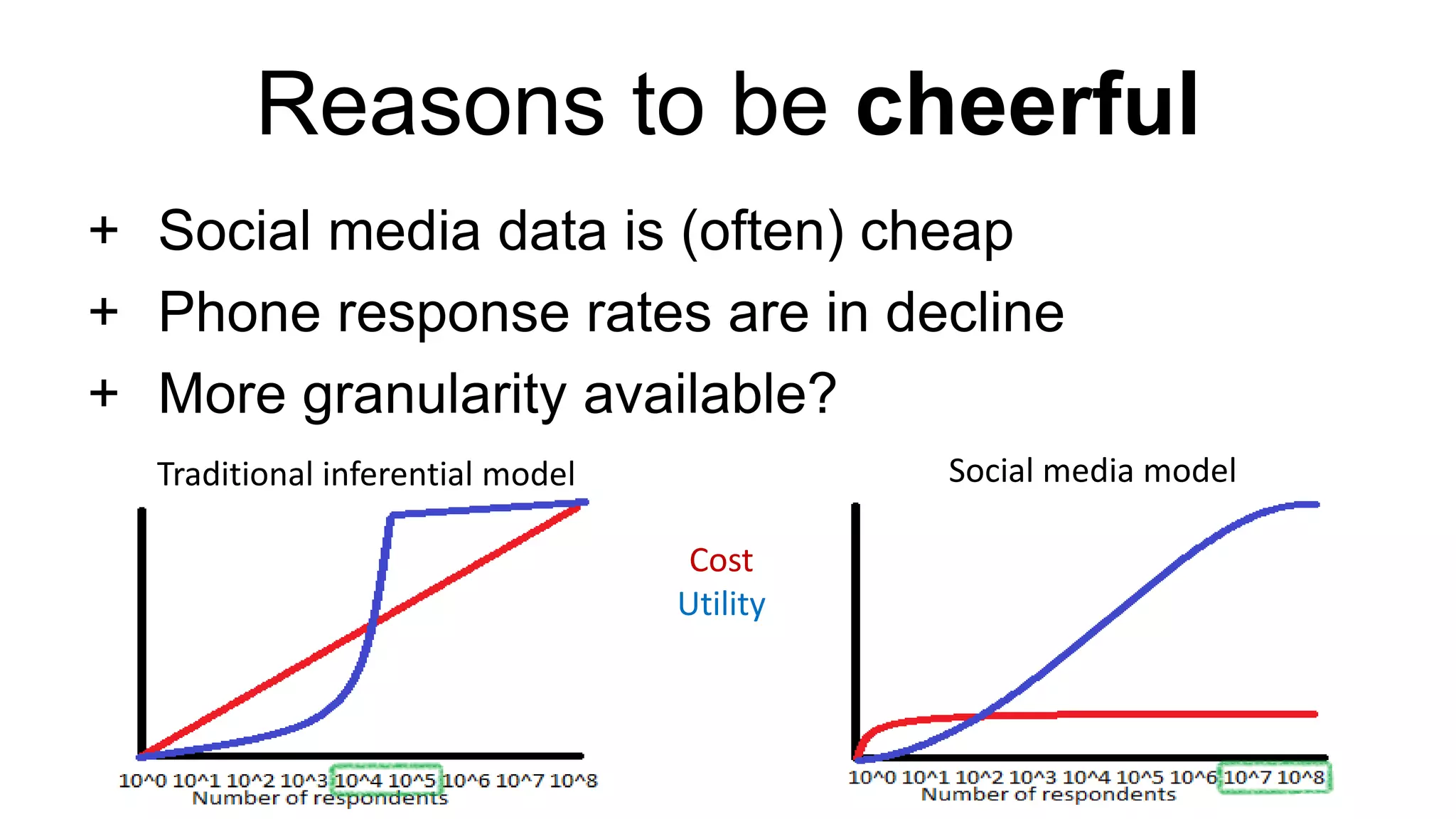

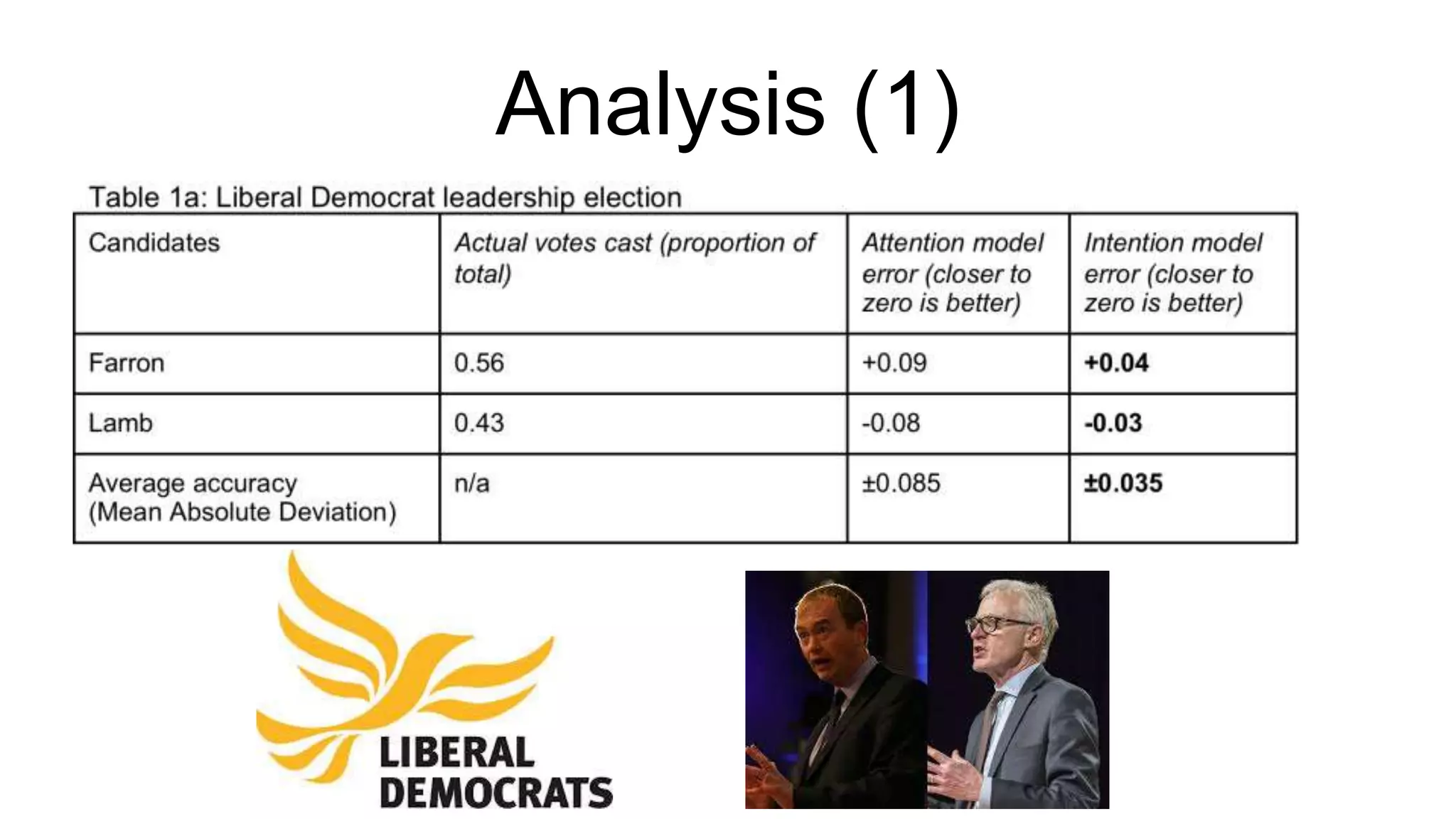

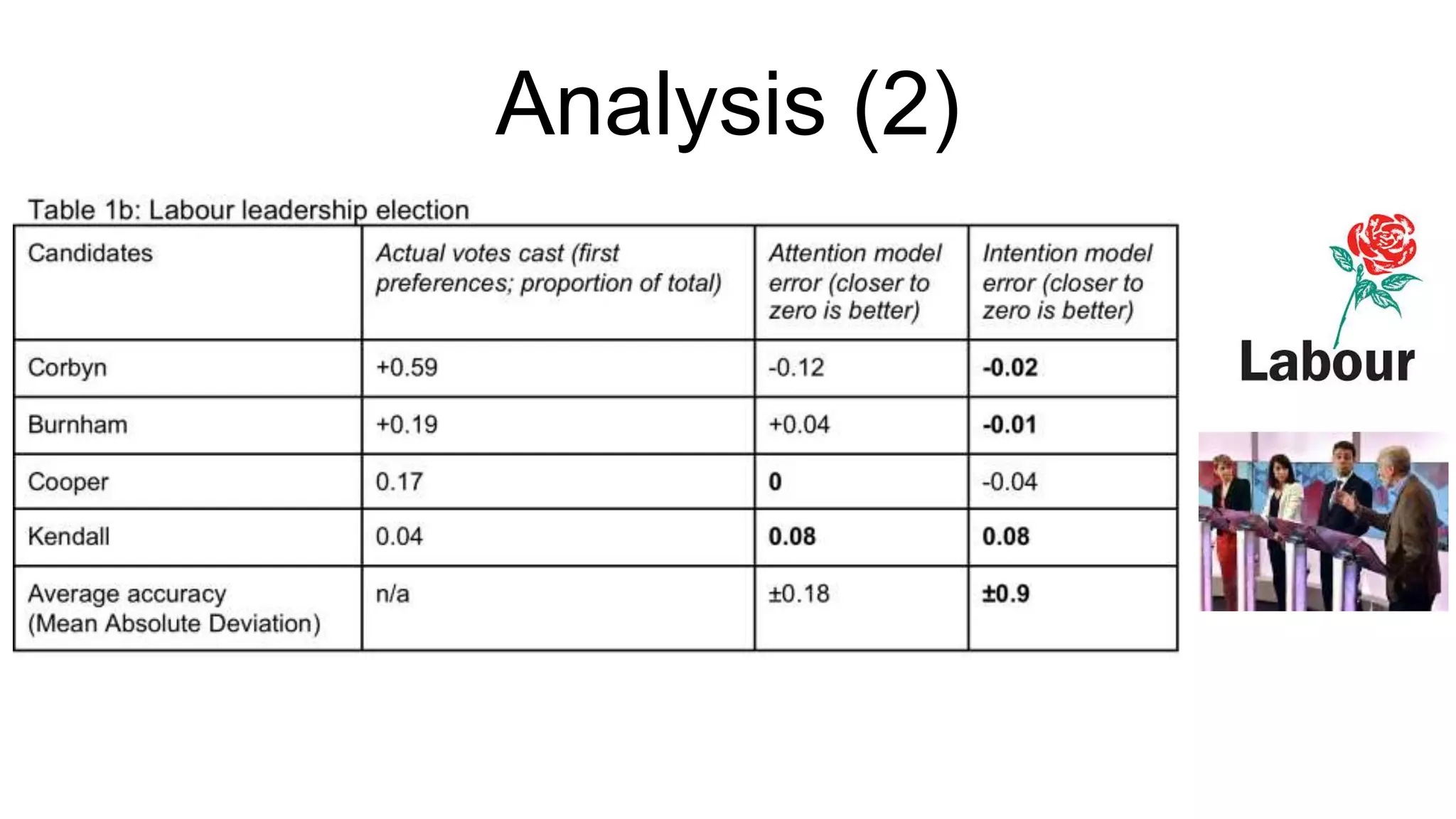

The document discusses the potential and challenges of using social media data for election predictions, highlighting the advantages of cost-effectiveness and granularity while noting reliability concerns, such as misinterpretation of latent messages. The authors emphasize an 'intention model' that collects direct voter declarations, which outperformed traditional models in predicting leadership elections in the UK Labour and Liberal Democrat parties. They conclude that, despite limitations, social media will be crucial for future election forecasting efforts.