This document is the introduction to the Global Information Technology Report 2009-2010, which examines the role of information and communication technologies (ICT) in fostering sustainability. It is edited by Soumitra Dutta of INSEAD and Irene Mia of the World Economic Forum. The report features articles that discuss how ICT can support sustainable development and competitiveness. It also includes the Networked Readiness Index rankings, country case studies on ICT strategies, and data on ICT adoption and usage. The introduction emphasizes the important role ICT will play in enabling renewed economic growth and promoting environmental and social sustainability.

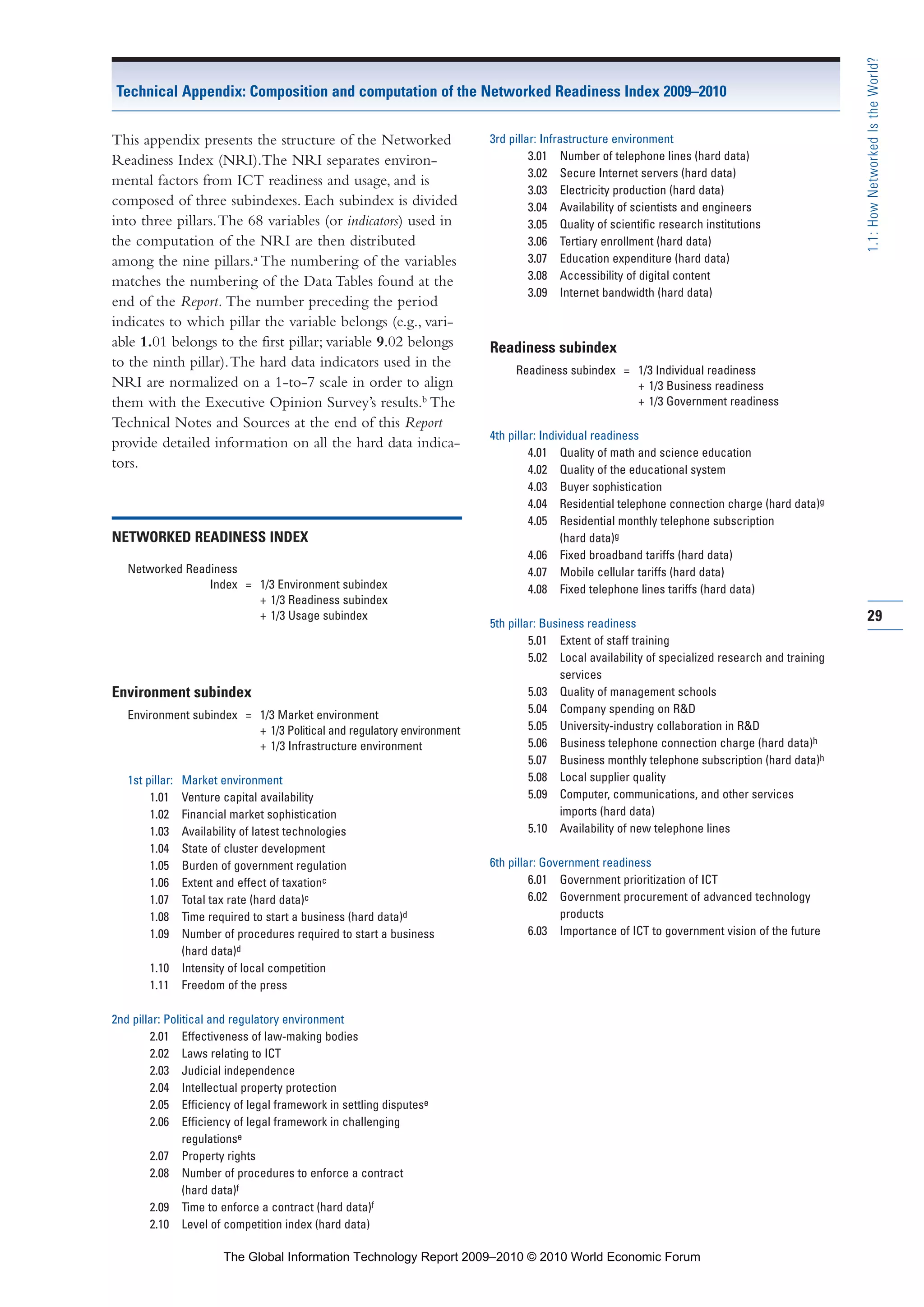

![benefits of Web 2.0 (as long as they can maintain the

quality as penetration keeps expanding). One of the

factors behind high penetration and quality appears to

be the structure of the market—the degree of diversity

in technology platforms (asymmetric digital subscriber

line [ADSL], cable, etc.) in particular.The countries and

cities with highest penetration and best quality of

broadband tend to have more diverse market structures.

High penetration and low-to-medium quality is not

an uncommon combination, and it generally indicates

rapid broadband deployment using existing copper infra-

structure that is now stretching the limits of network

capacity (as appears to be the case of London and

Toronto, for instance). High quality and low penetration

is a rare combination that can reflect small city “niches”

and is not present in our sample. Finally, low penetration

and quality—which affects a number of cities in our

sample—indicates the signi-ficant challenge in taking

advantage of the opportunity of broadband connectivity.

An interesting leapfrogging phenomenon is reflected in

cities such as Budapest, Moscow, Prague, and St

Petersburg, where limited legacy networks paradoxically

created the impetus for investing in network technology

that allows for better broadband quality.

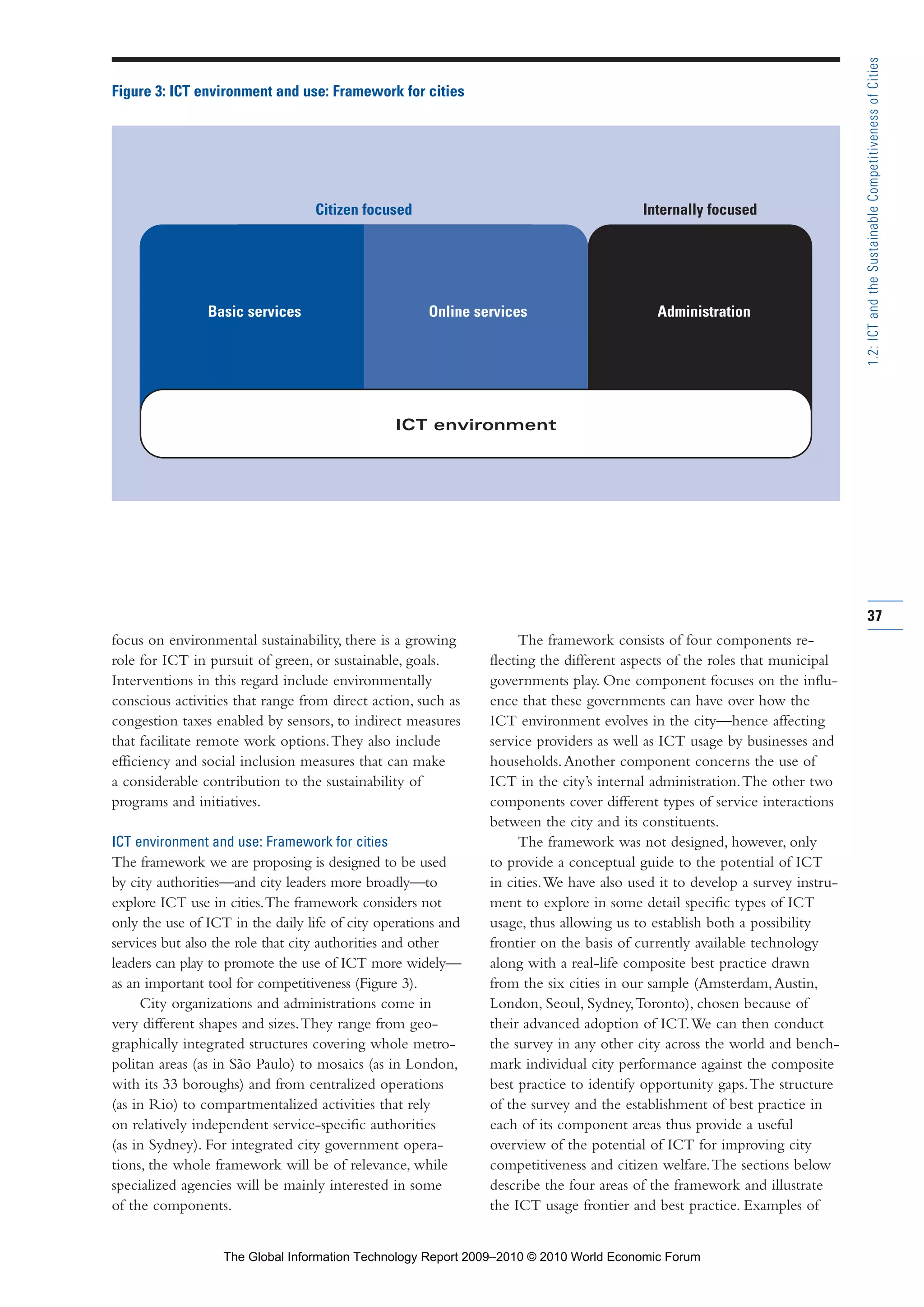

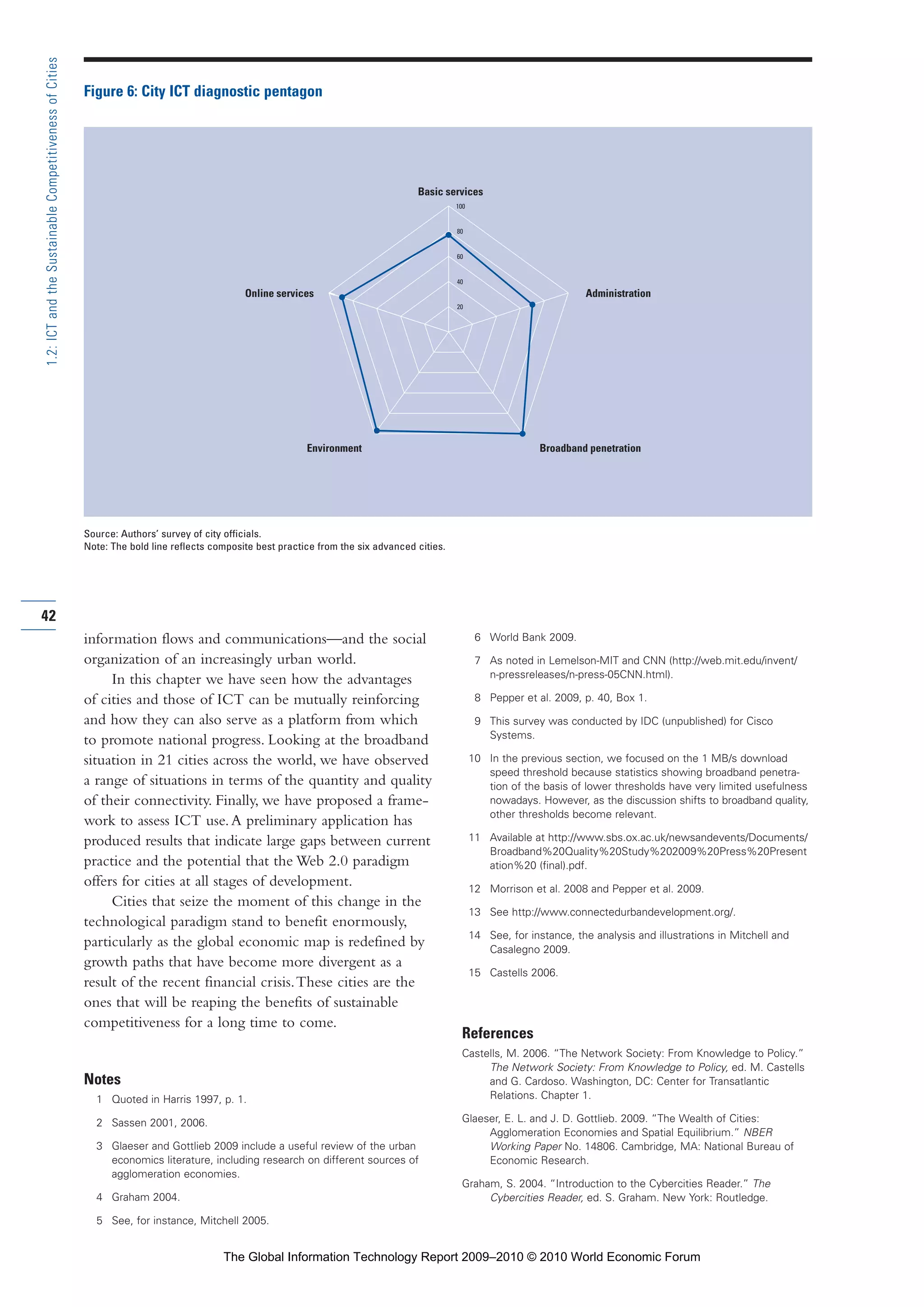

ICT environment and use

As we noted above, the global city phenomenon raises the

competitiveness stakes.What does it take to make a city

competitive in the global arena? What can city leaders

(be they in government, business, or civil society organi-

zations) do to improve their city’s competitiveness—and

sustain it? We believe that a large part of the answer has

to do with ICT—and, more specifically, with networks.

The purpose of the assessment exercise underway is

to provide an overview of the ways in which municipal

governments influence the ICT environment in their

cities and to explore in detail how they use ICT in city

operations.The assessment uses the framework developed

for the purpose by Cisco (and a survey instrument

designed with help from Illuminas Global PLC).

This framework was specifically designed to explore

the environment and use of ICT in cities and to provide

a diagnostic perspective in enough detail that it can guide

the formulation of action plans.The first stage of the

assessment has already allowed us to establish best prac-

tice boundaries. In the second stage, individual cities can

be benchmarked against both the frontier of possibilities

and existing best practice so that avenues for progress—

or opportunity gaps—can be identified.

Cities, of course, operate under an umbrella of

national policies, regulations, infrastructures, and capabil-

ities.A chapter in The Global InformationTechnology Report

(GITR) 2007–2008 explored the importance of the bal-

ance between the “ecosystem” (policies and regulations

affecting ICT directly, as well as the business and inno-

vation environments) and investments in infrastructure

and capabilities.A chapter in The GITR 2008–2009

then proposed an approach for developing national

net strategies, many aspects of which are also relevant for

cities.12

The complementary framework we propose here

is specifically focused on cities.

Before going into the specifics of the ICT environ-

ment and use framework, it is worth stepping back and

thinking about how competitiveness and ICT relate to

three major goals that most city leaders have in mind:

• Economic growth and job creation. This

is one of the main aims of competitiveness

improvements—which attract investment and

generate a virtuous circle that takes advantage of

the potential agglomeration economies. Basic

infrastructure is a key competitiveness factor.As

broadband becomes the basic infrastructure factor

for the knowledge economy (with a significant

impact on total factor productivity), it also moves to

the center of the competitiveness strategies of cities.

• Social welfare. As information about city condi-

tions flows, and as people across the world become

more mobile, the performance of a city in terms of

services offered to its citizens is a major determinant

of whether the city is seen as an attractive place to

live and work—hence able to draw and retain tal-

ented people, which is another major competitive-

ness factor. ICT can be used to achieve dramatic

improvements in efficiency and effectiveness in the

provision of services, as well as to reduce the trans-

action costs in the city-citizen relationship—at both

the economic and political levels.

• Environmental sustainability. Increasingly a con-

cern for citizens and businesses, the choices made by

a city and their impact on the environment are also

becoming a crucial factor of long-term competitive-

ness. ICT offerings are more and more able to address

environmental sustainability concerns in ways that can

also be aligned with social and economic goals.This

win-win approach is the focus of efforts in many

cities across the world. Pilot programs and informa-

tion sharing, among other things, are being promoted

by a collaborative effort among the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology (MIT), Cisco, and global

cities that focuses on the use of ICT to launch a new

wave of innovation in urban development affecting

the flow of people, knowledge, traffic, and energy.13

Conventional discussions of competitiveness have

focused mostly on factors in the economic and social

spheres, but increasingly factors from the “green” sphere

are taking center stage and should now be considered an

integral part of sustainable competitiveness.

Because city governments and other local authori-

ties in metropolitan areas are increasingly expected to

36

1.2:ICTandtheSustainableCompetitivenessofCities

Part 1.r2 3/2/10 4:40 AM Page 36

The Global Information Technology Report 2009–2010 © 2010 World Economic Forum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cusersdesktop2010gitr2009-2010fullreportfinal-100402152331-phpapp01/75/The-Global-Information-Technology-Report-2009-2010-56-2048.jpg)

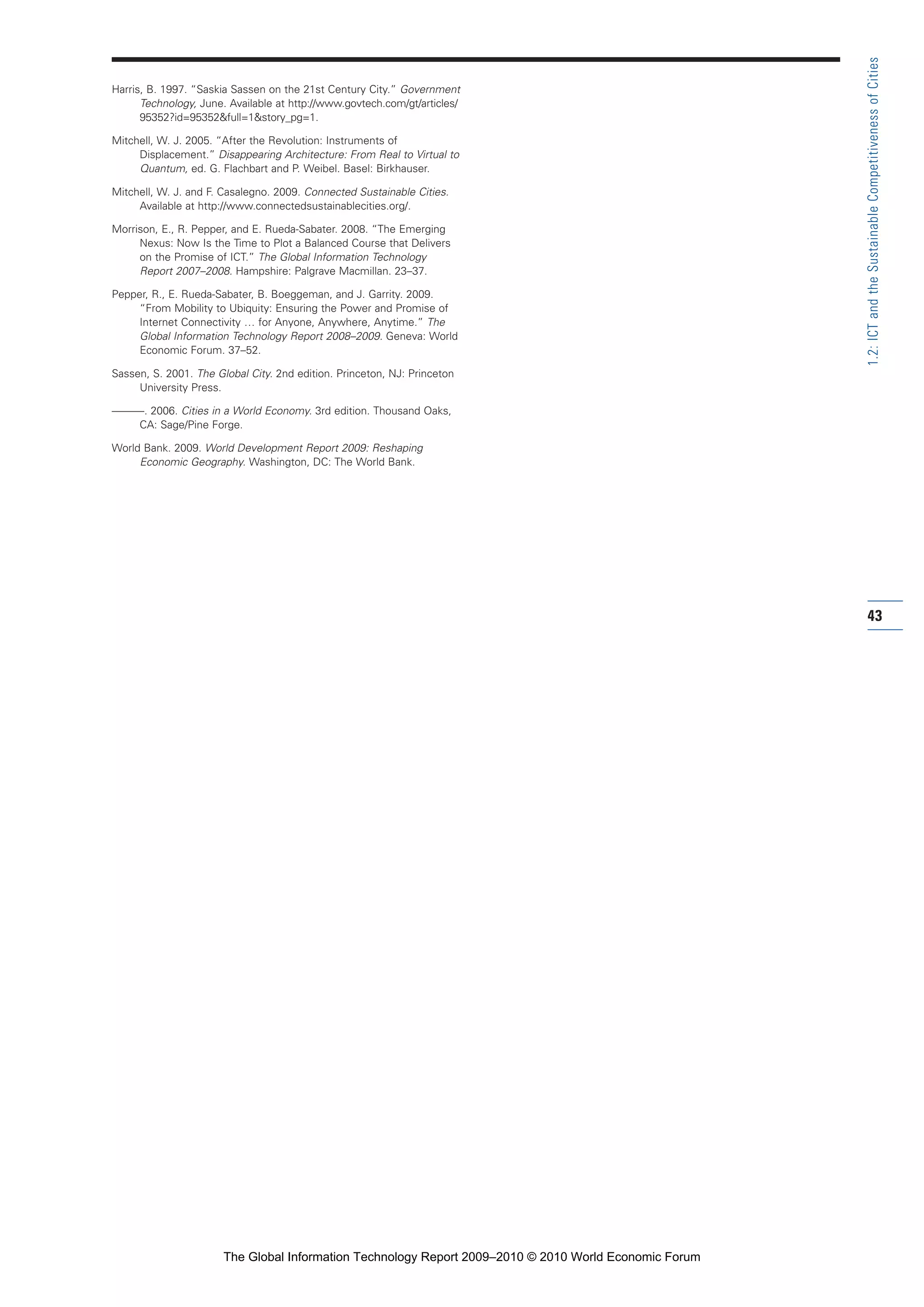

![Building total

Building envelope

(wall, roof, window)

Heating, ventilation,

and air conditioning

Lighting

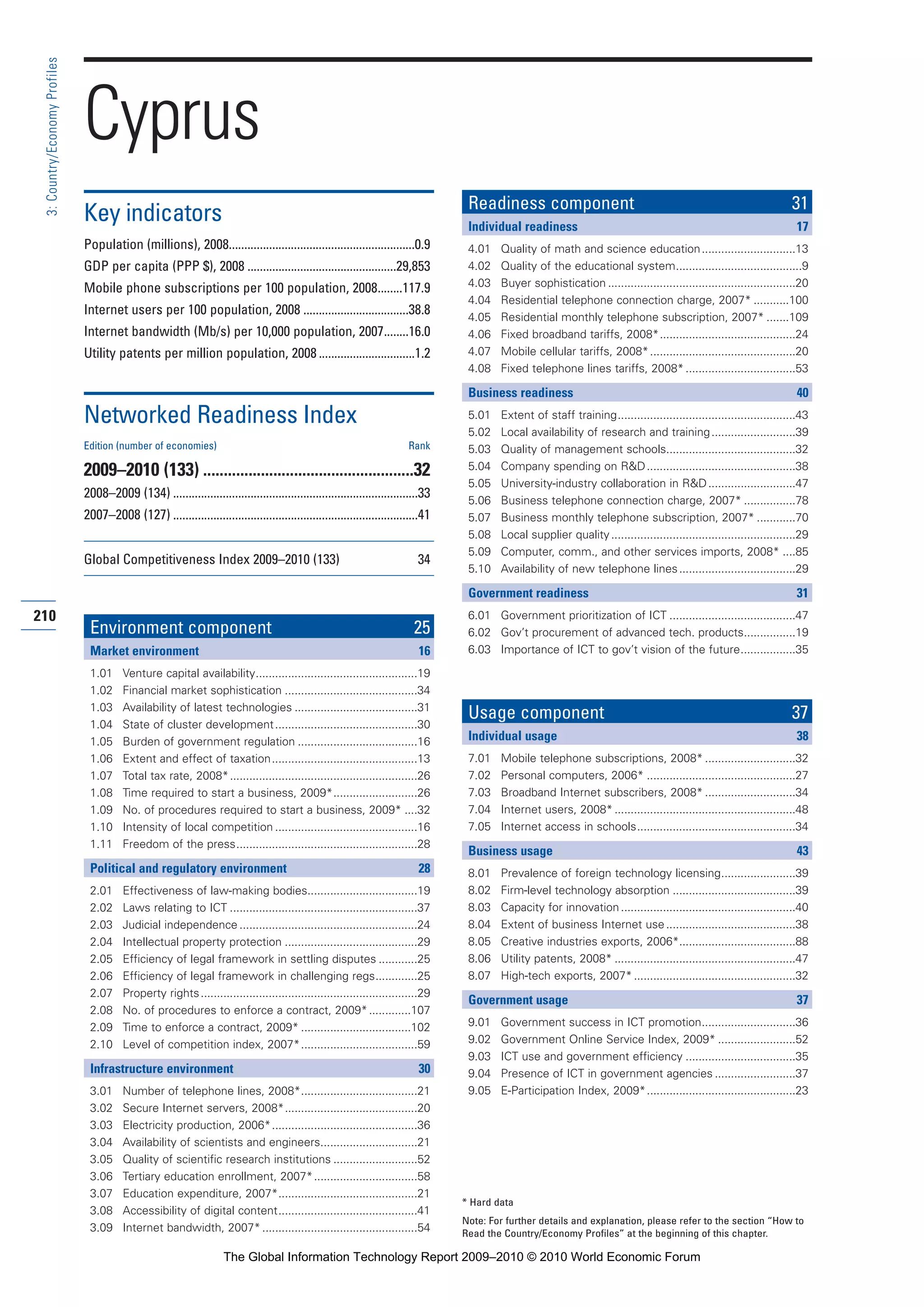

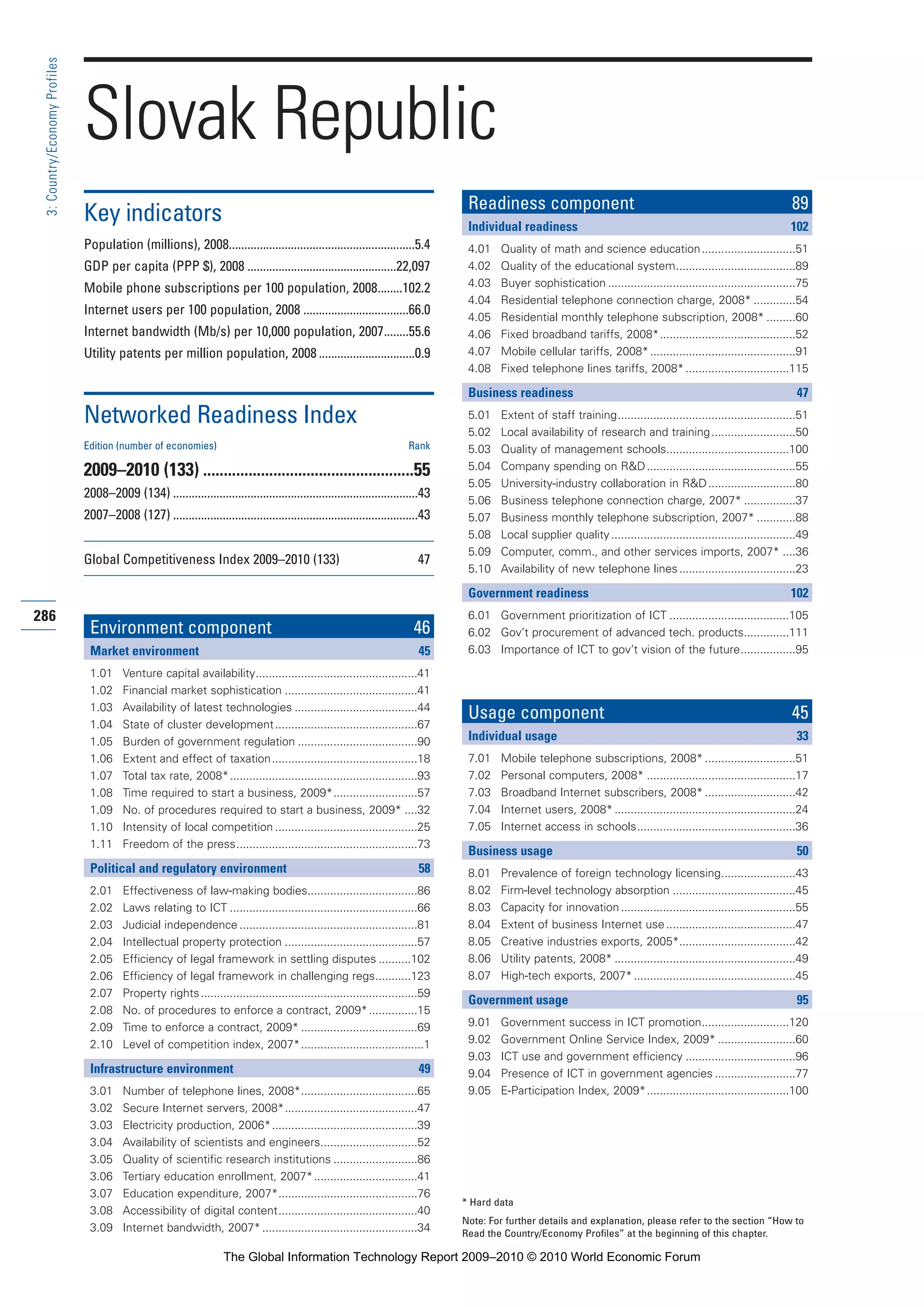

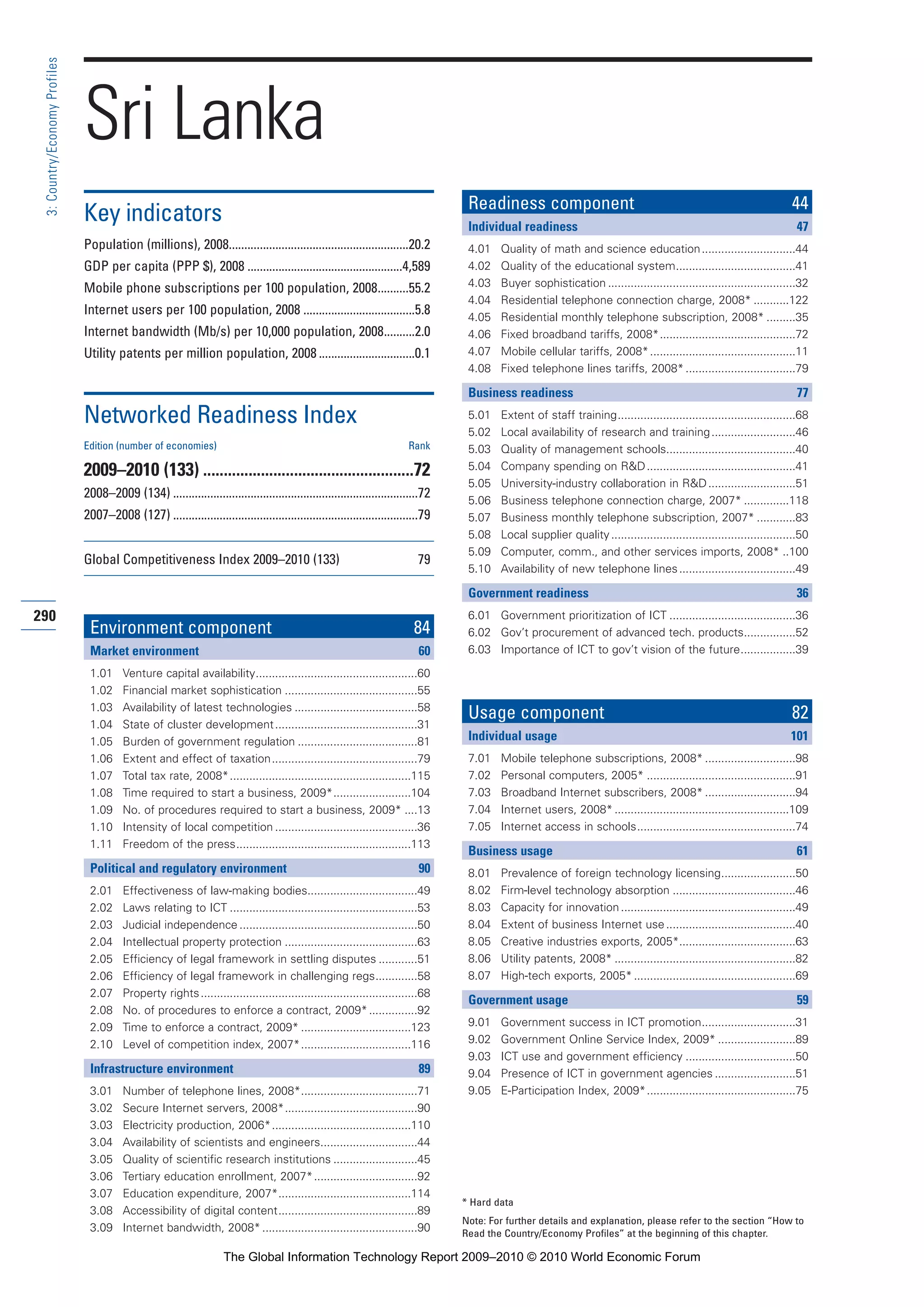

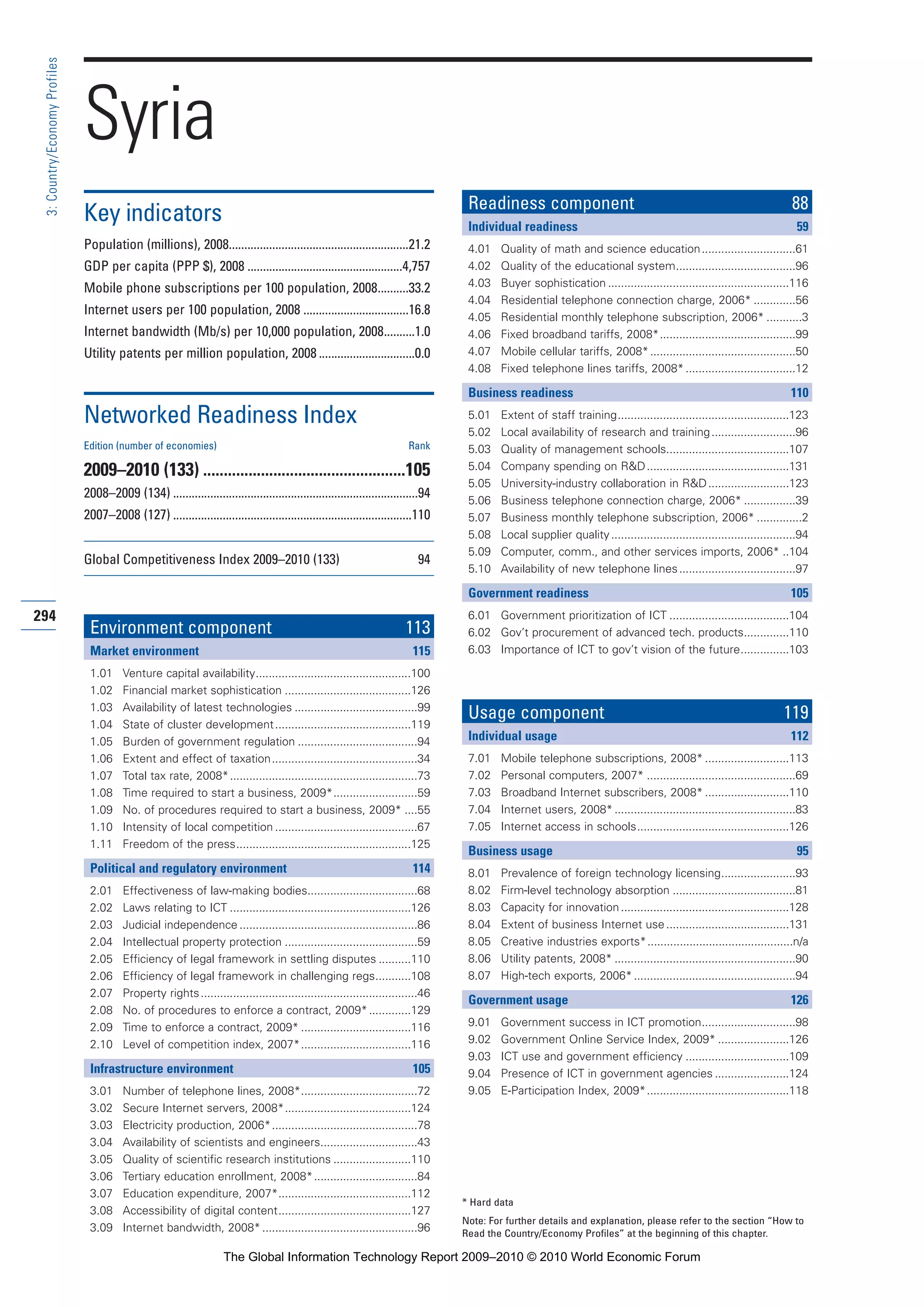

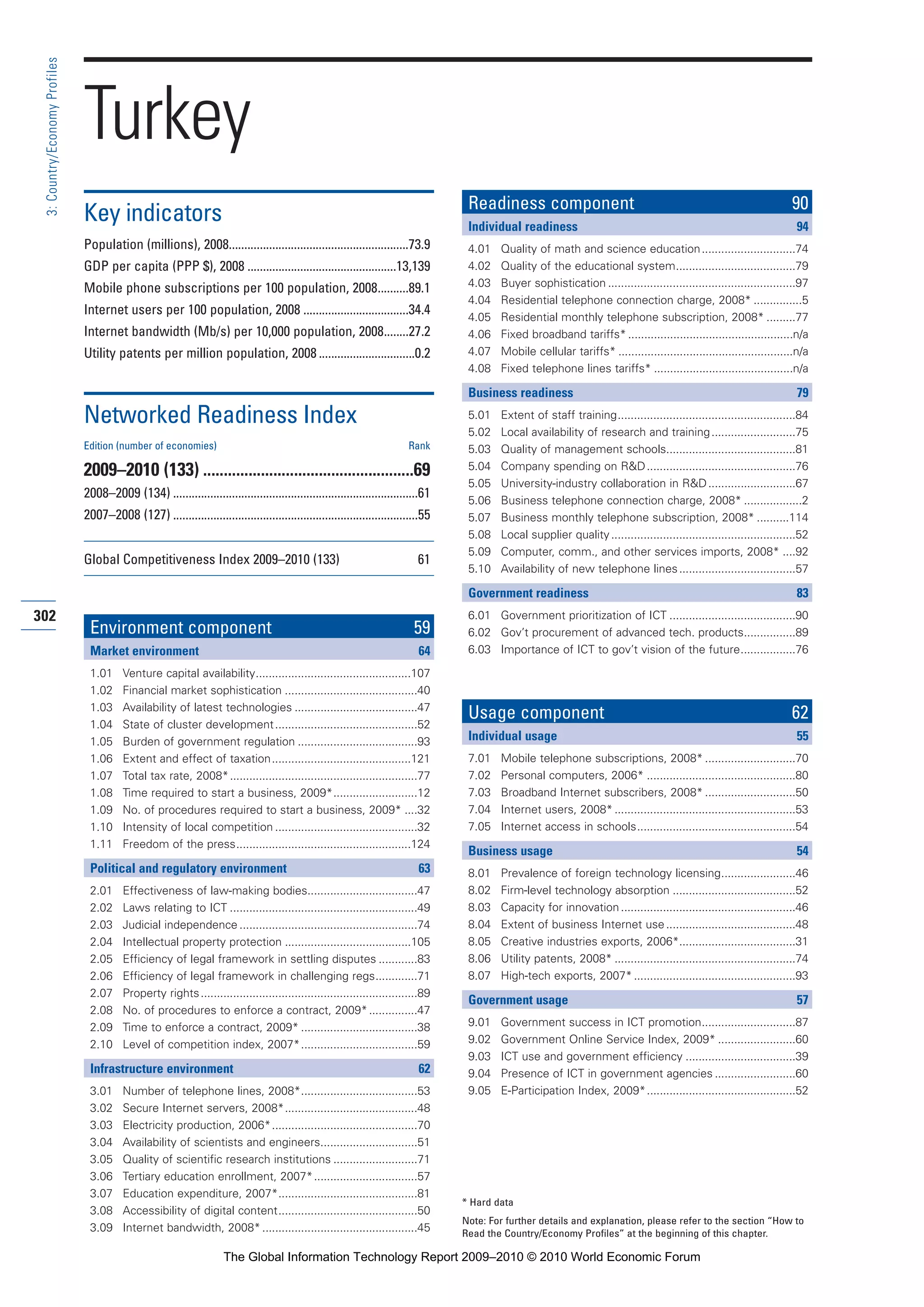

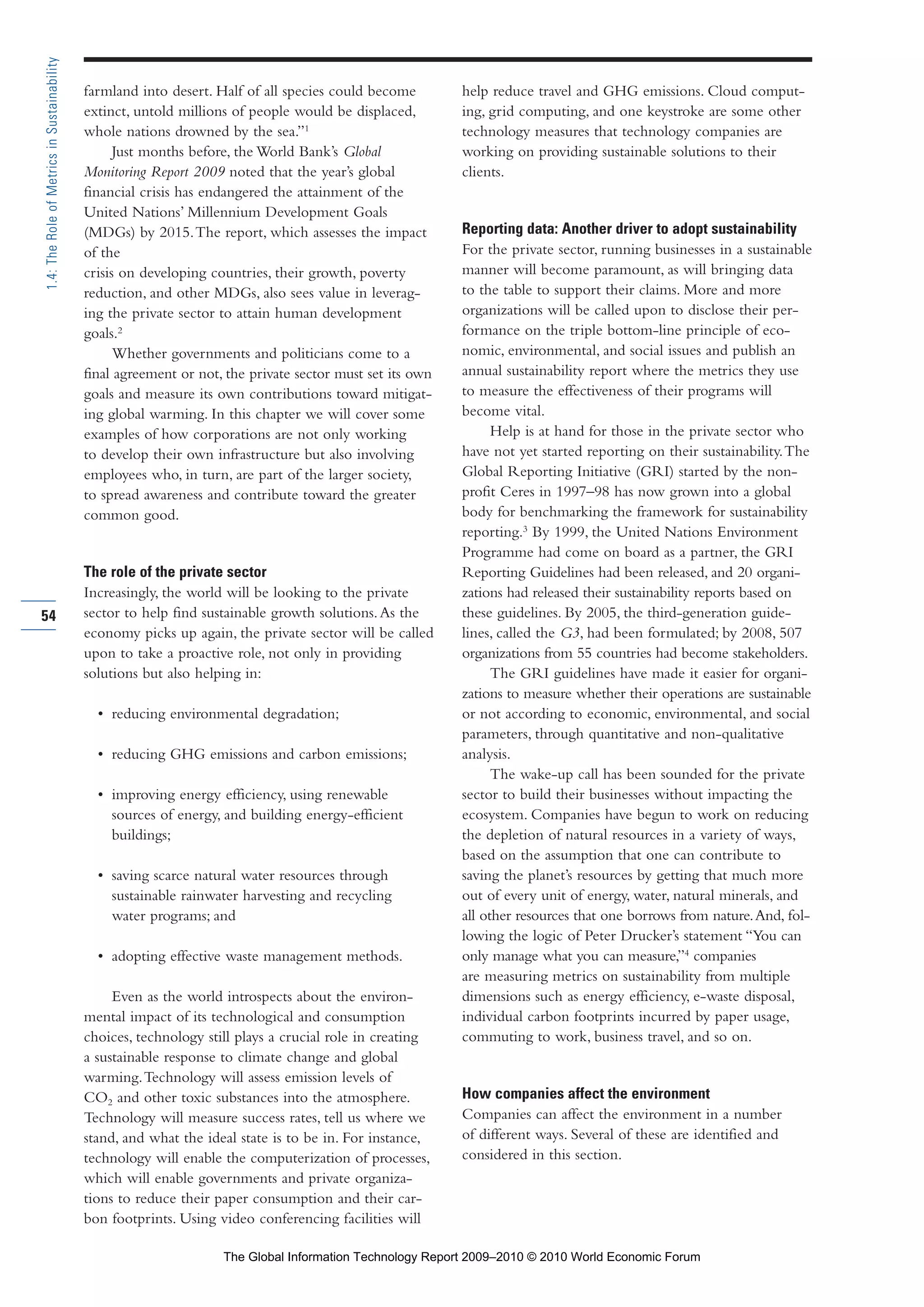

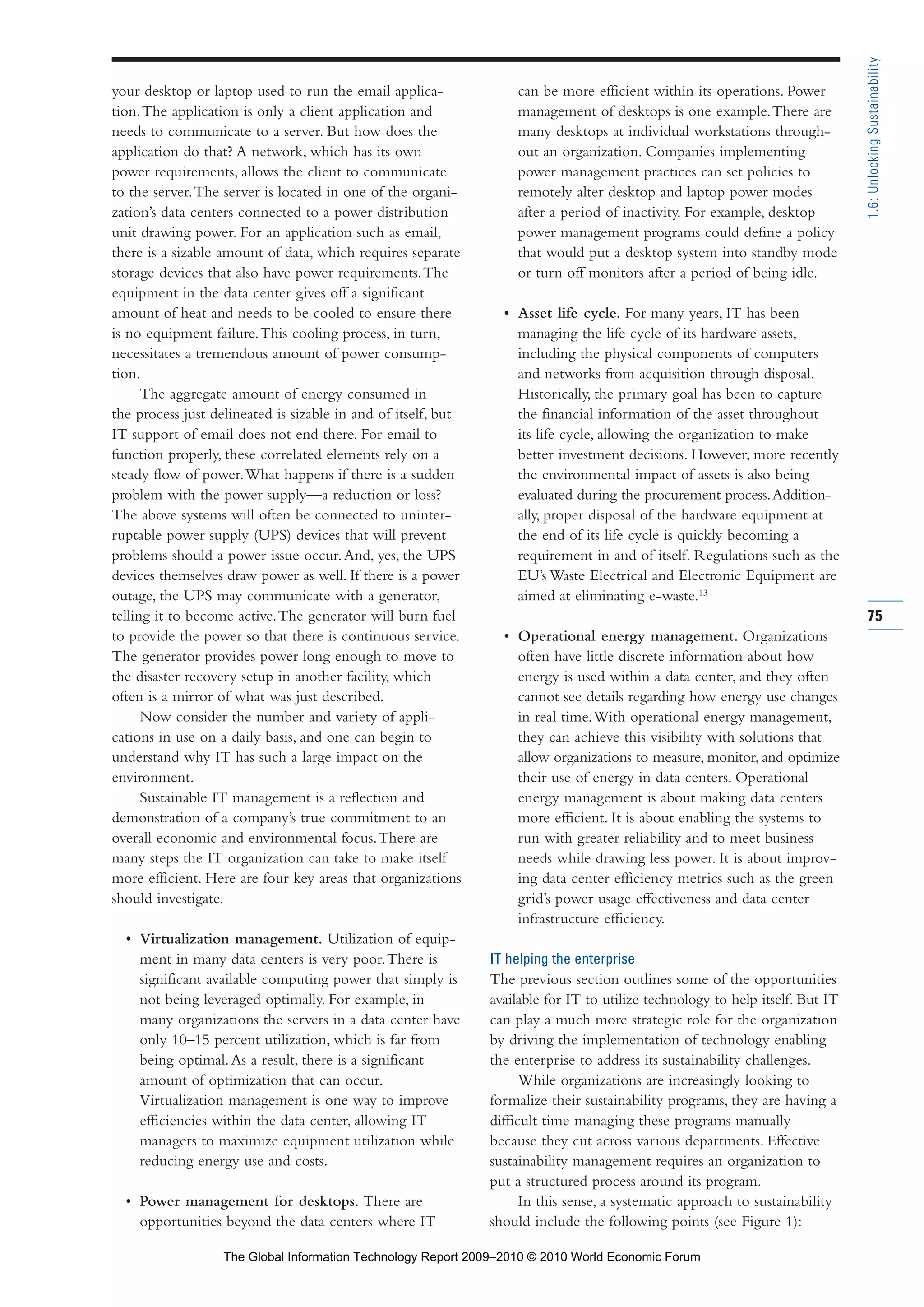

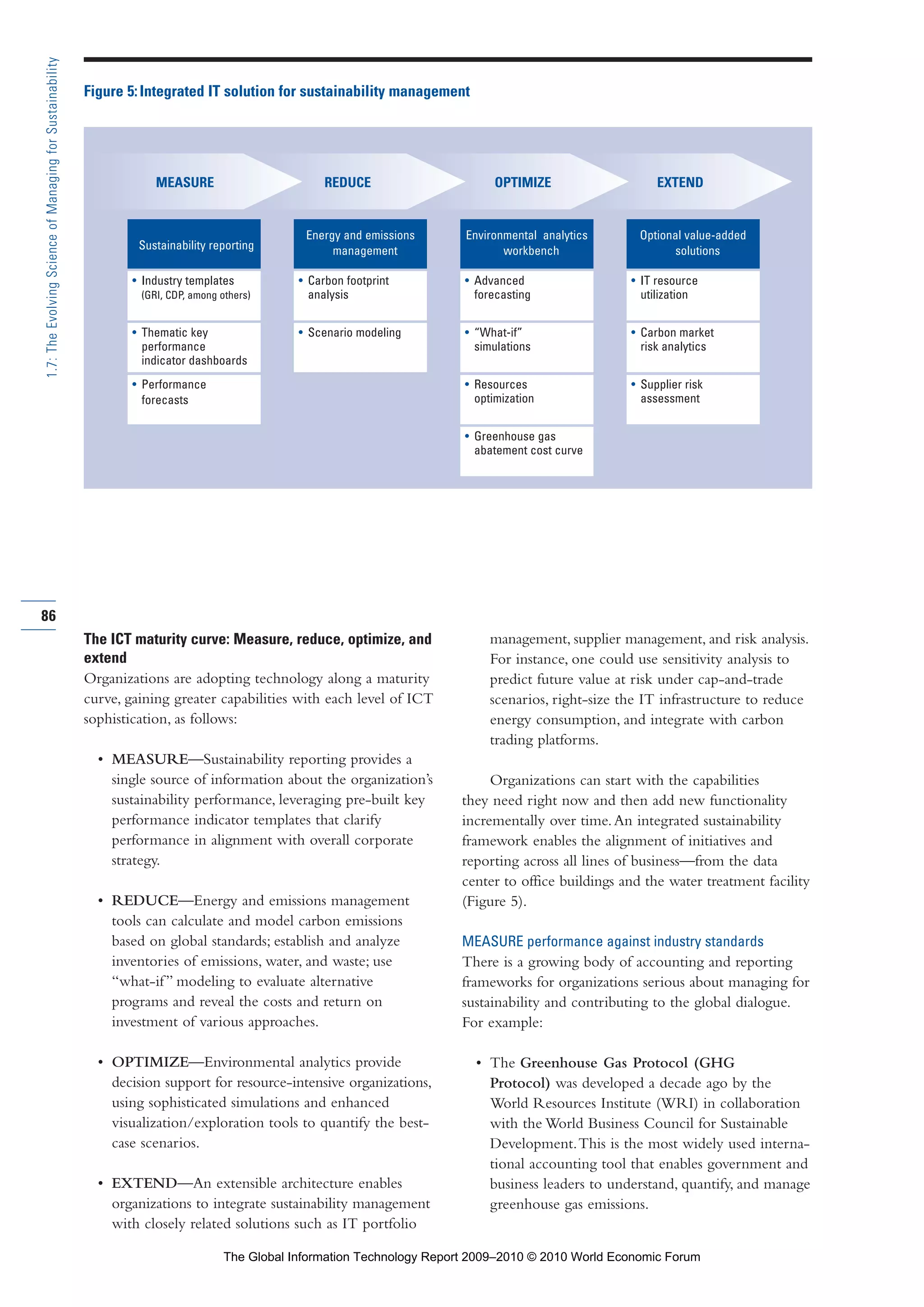

Recently, conscious efforts have been made in the

private sector to measure data accurately at a more

granular level.This exercise has provided deep insights

into areas where further improvements can be made in

the efficiency of current operations.

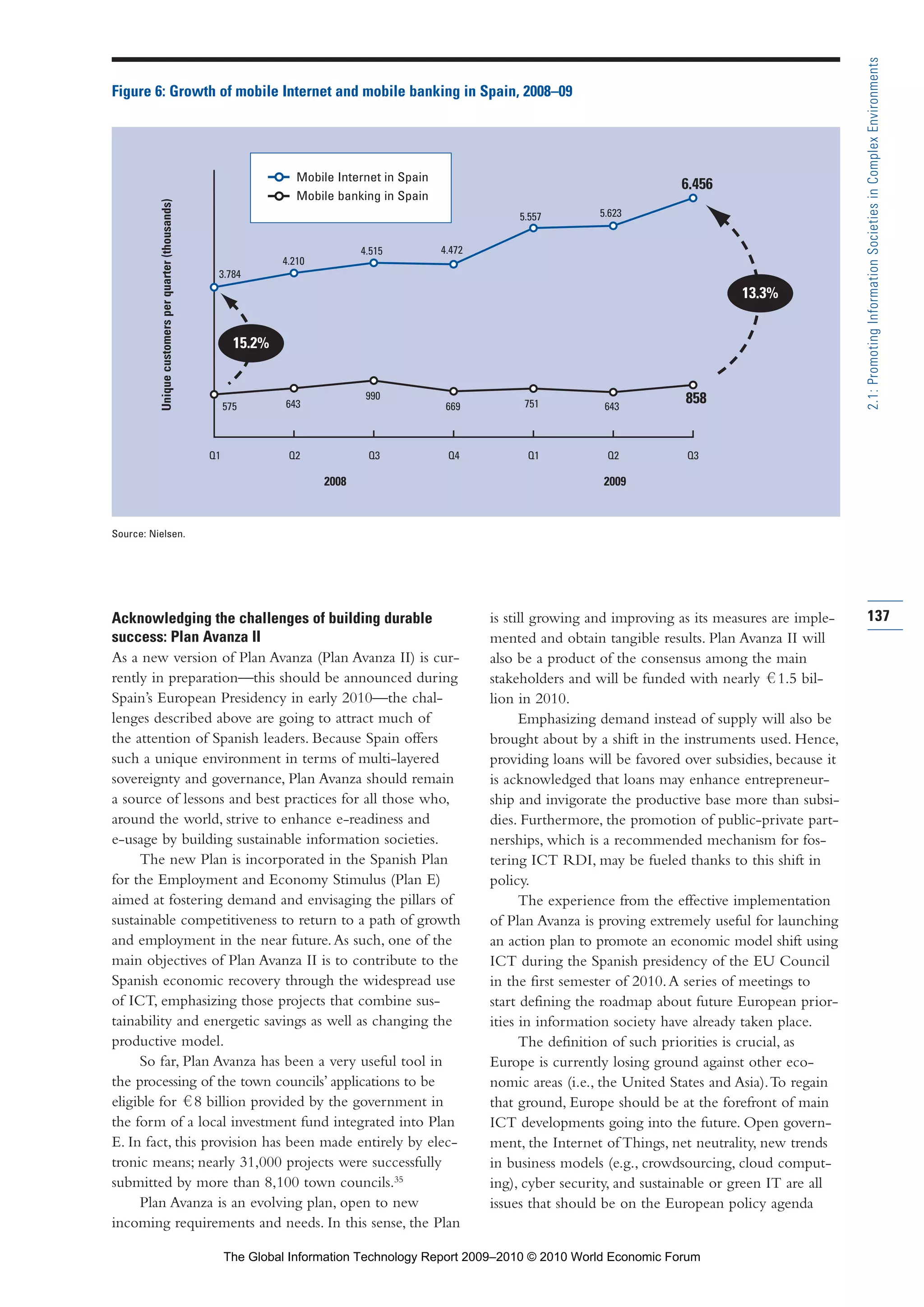

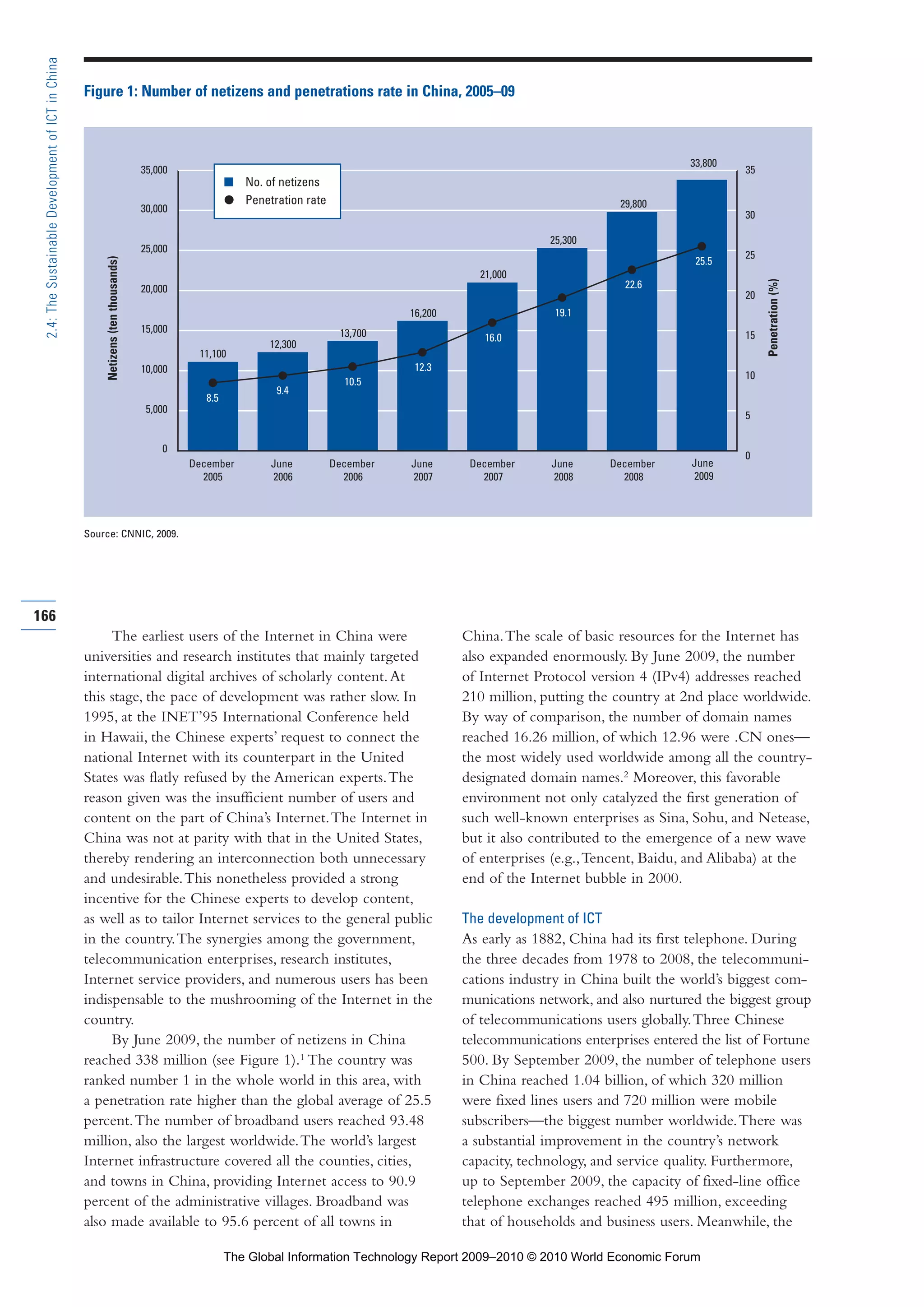

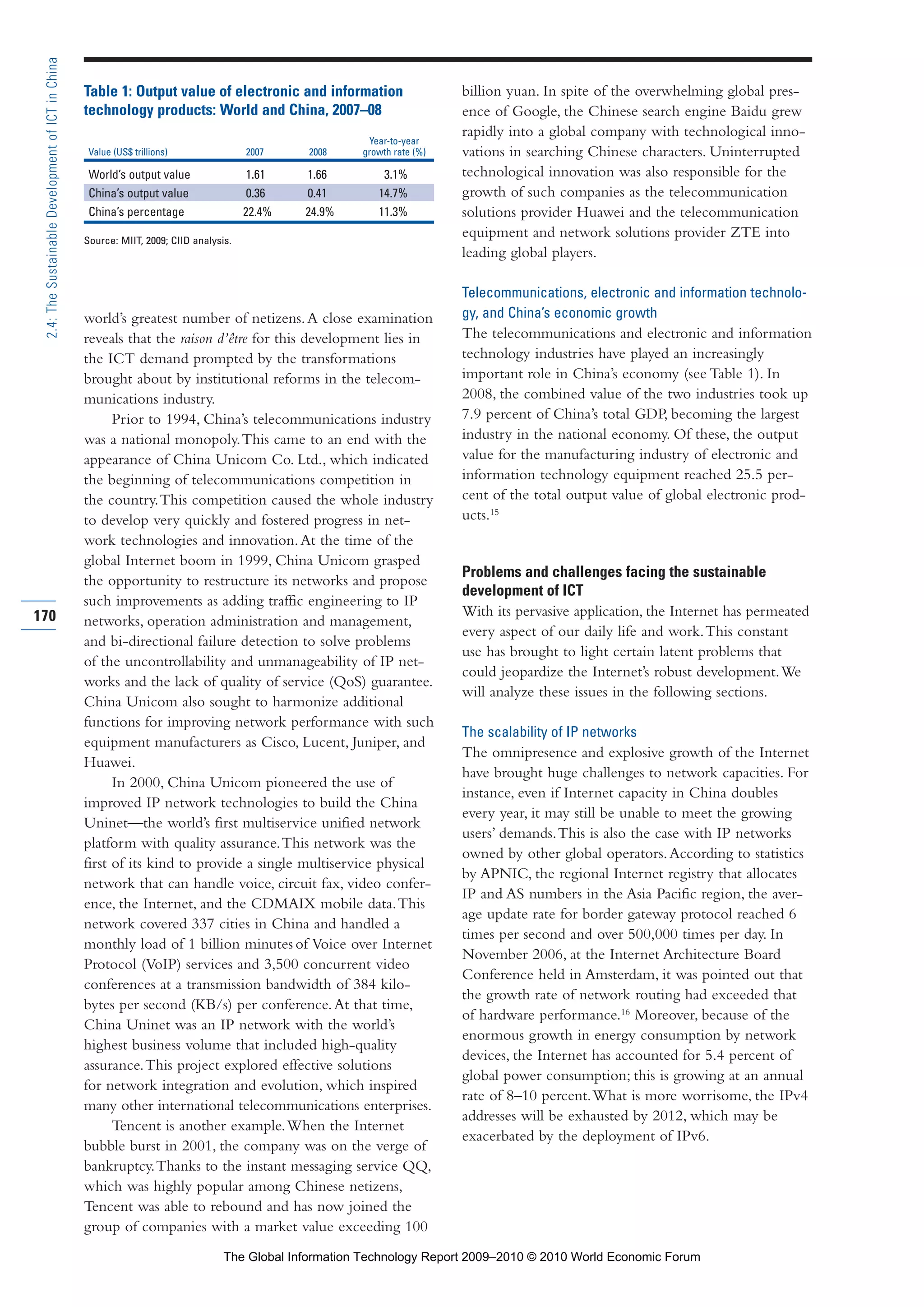

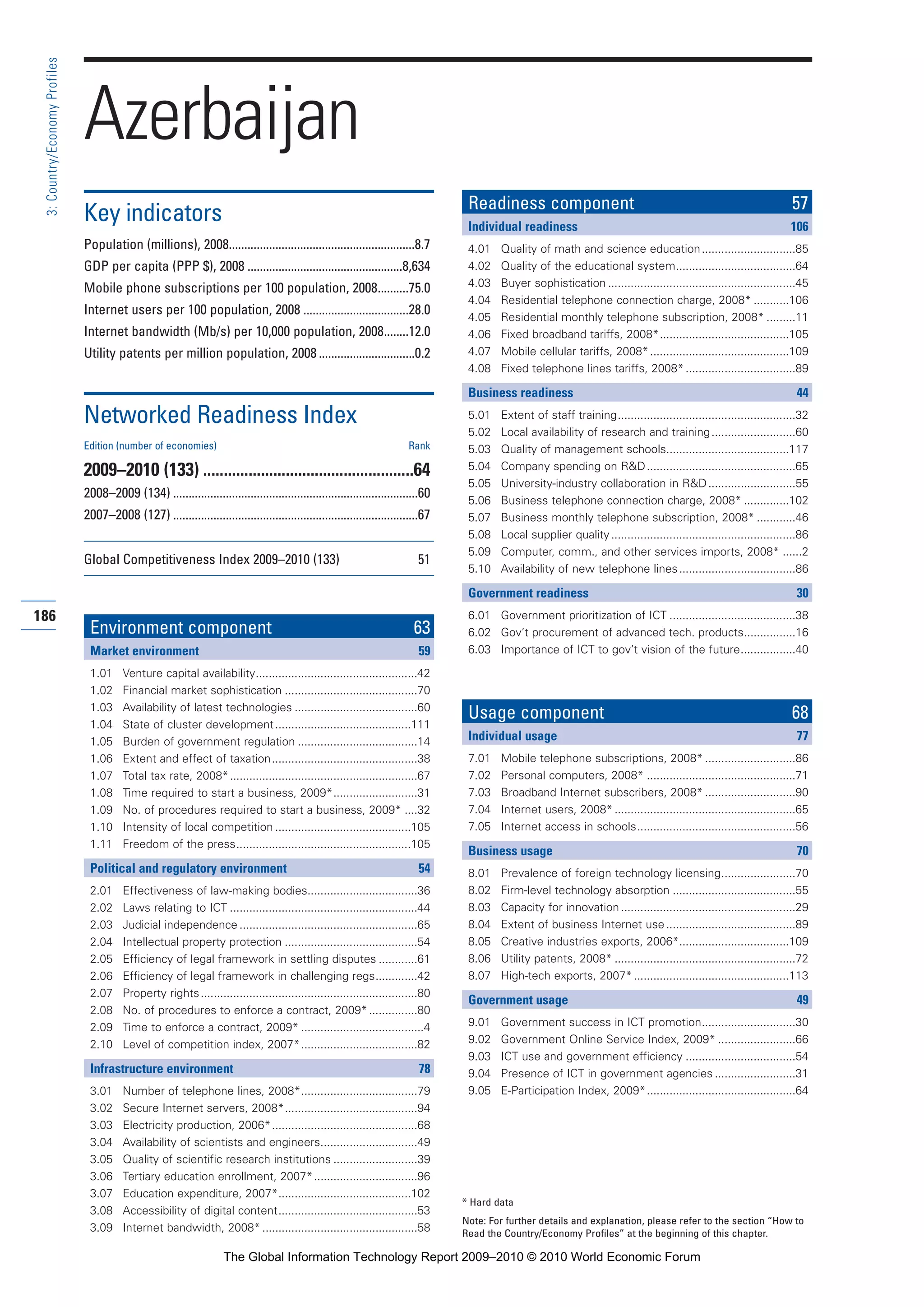

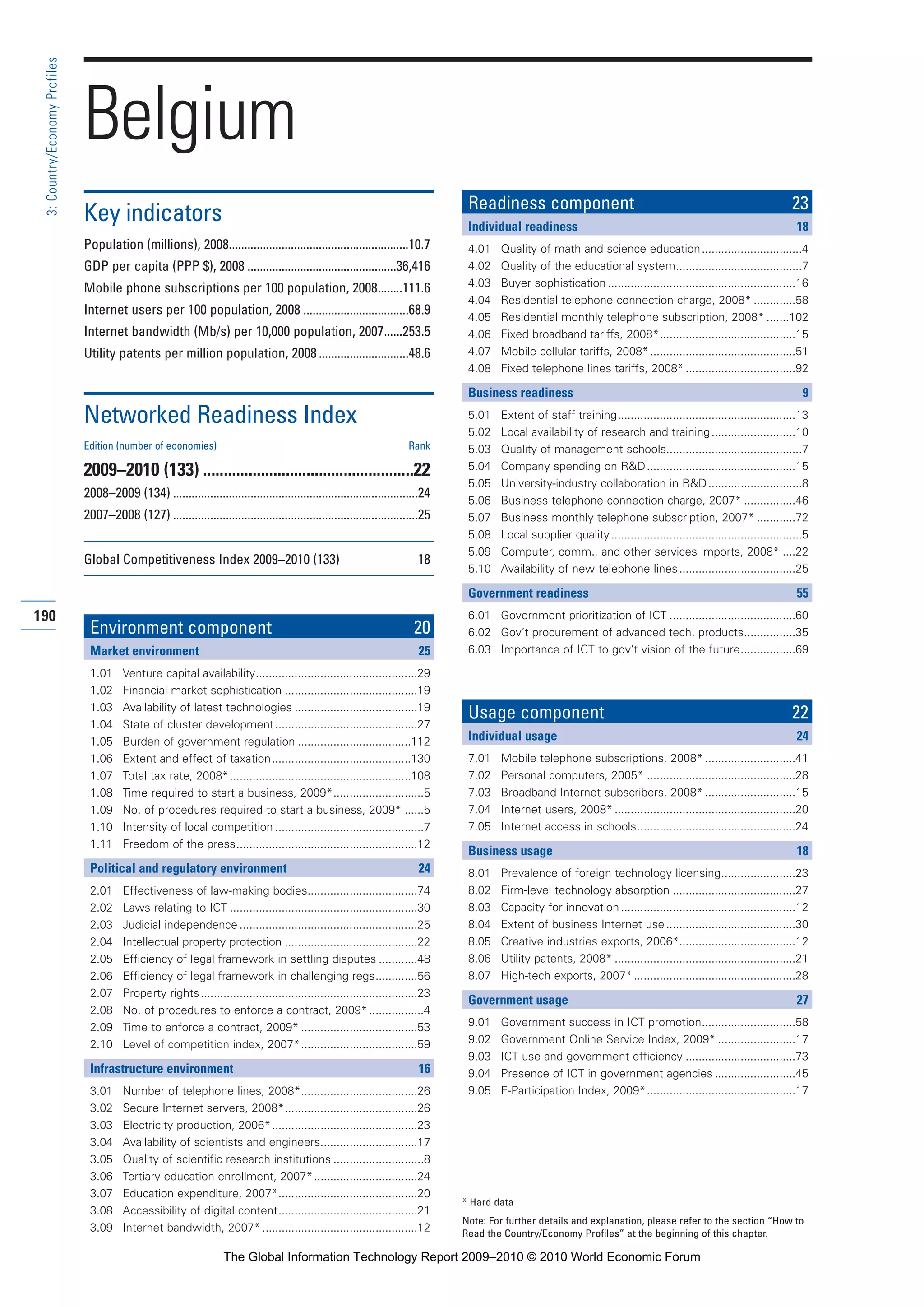

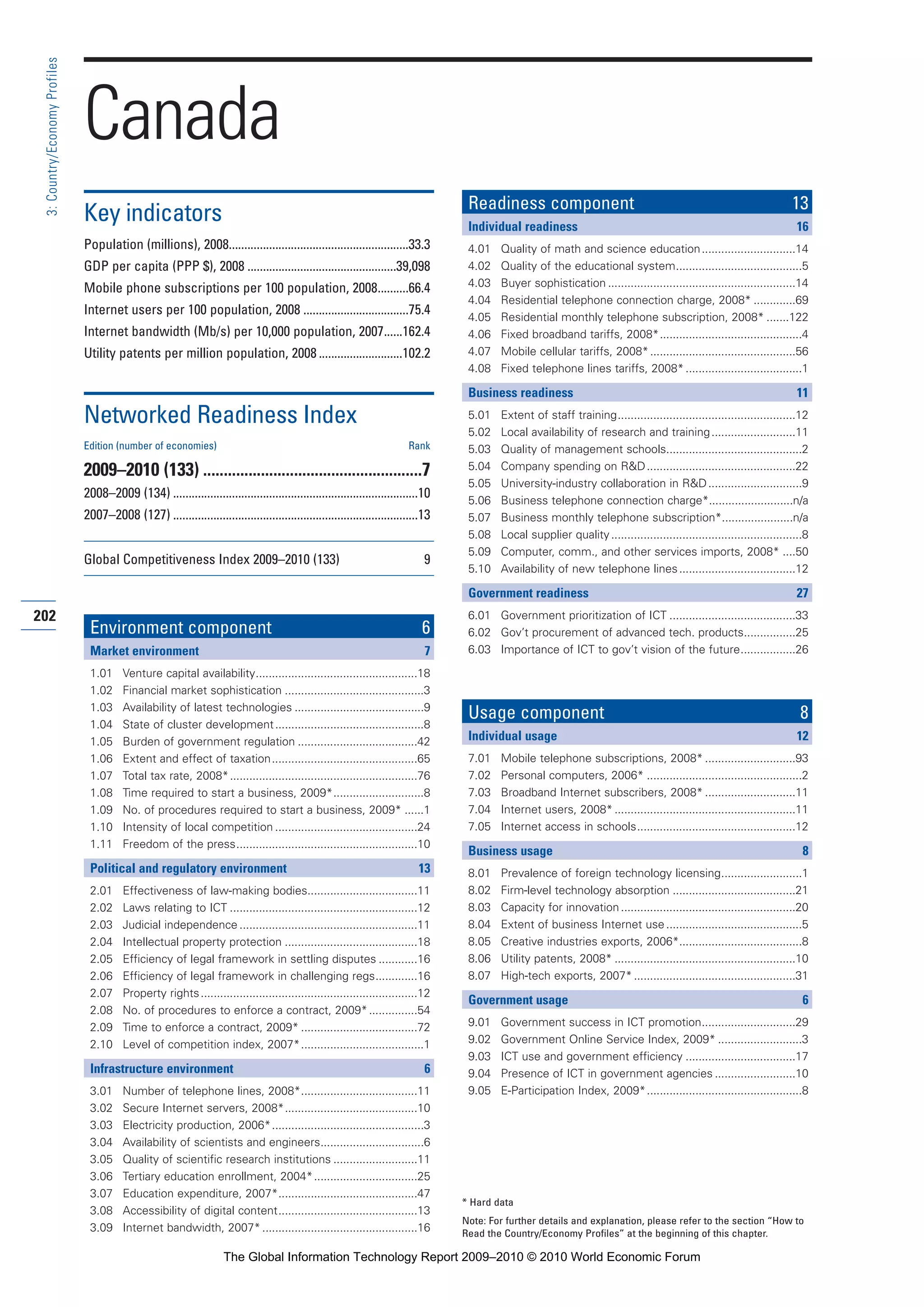

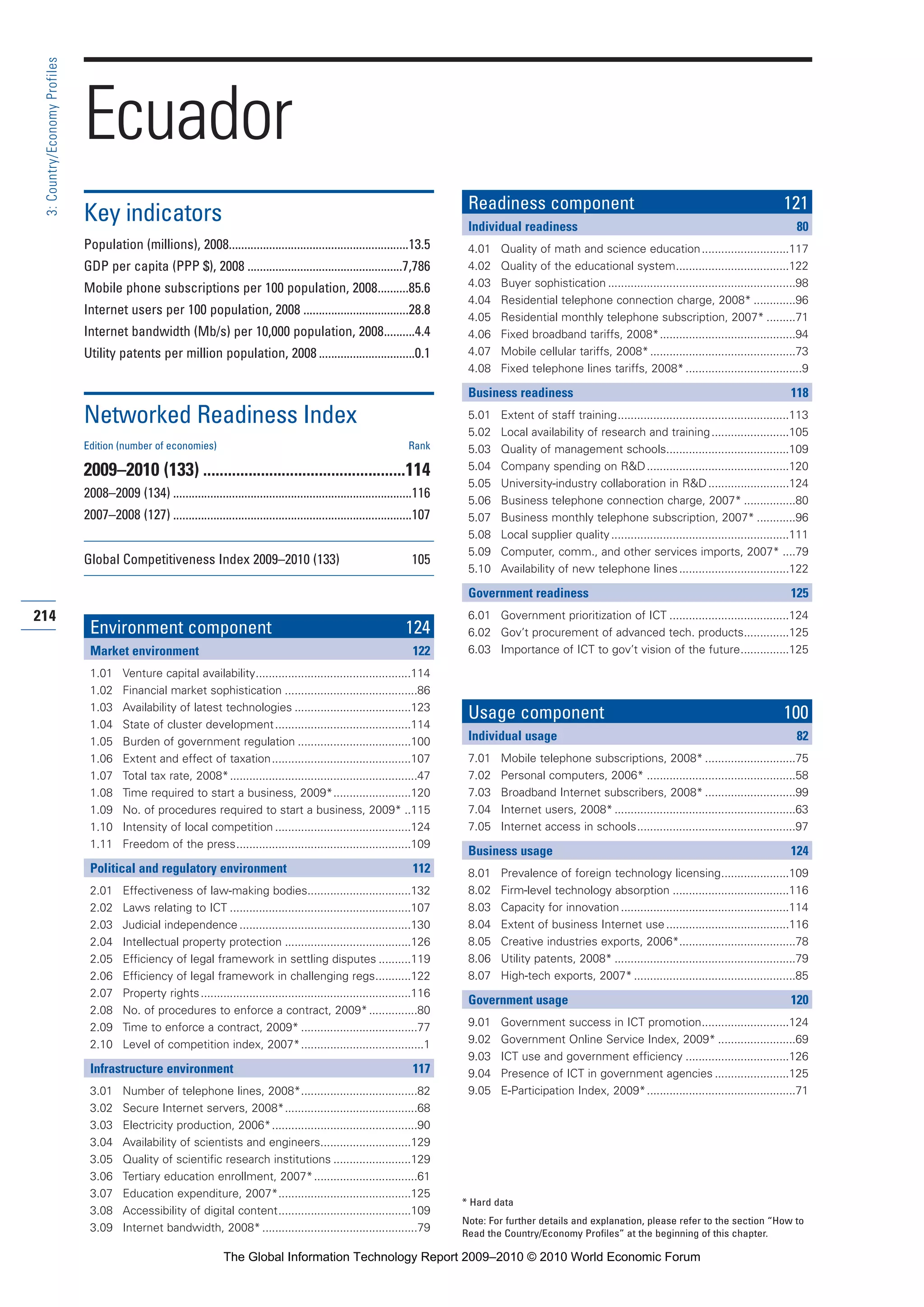

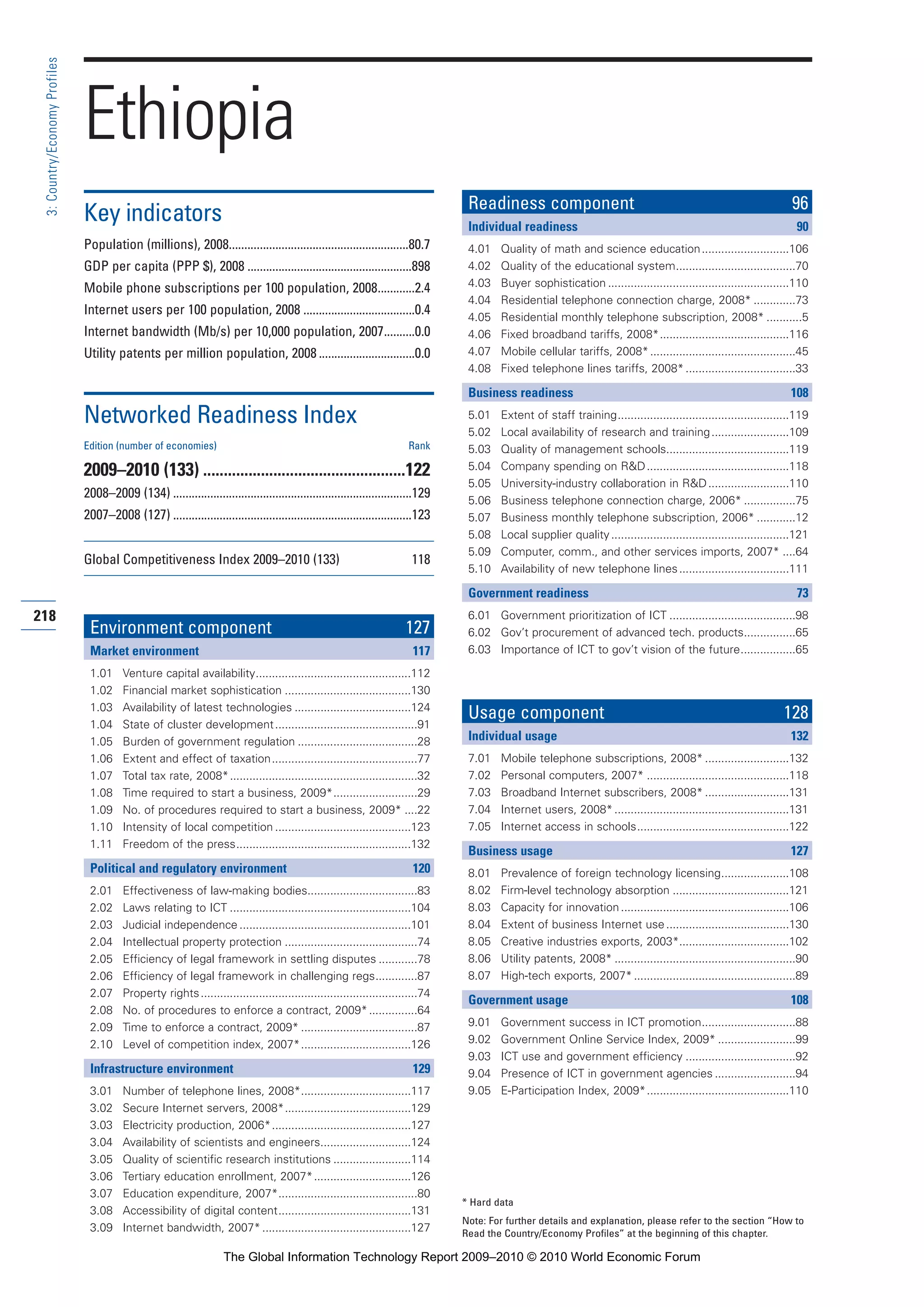

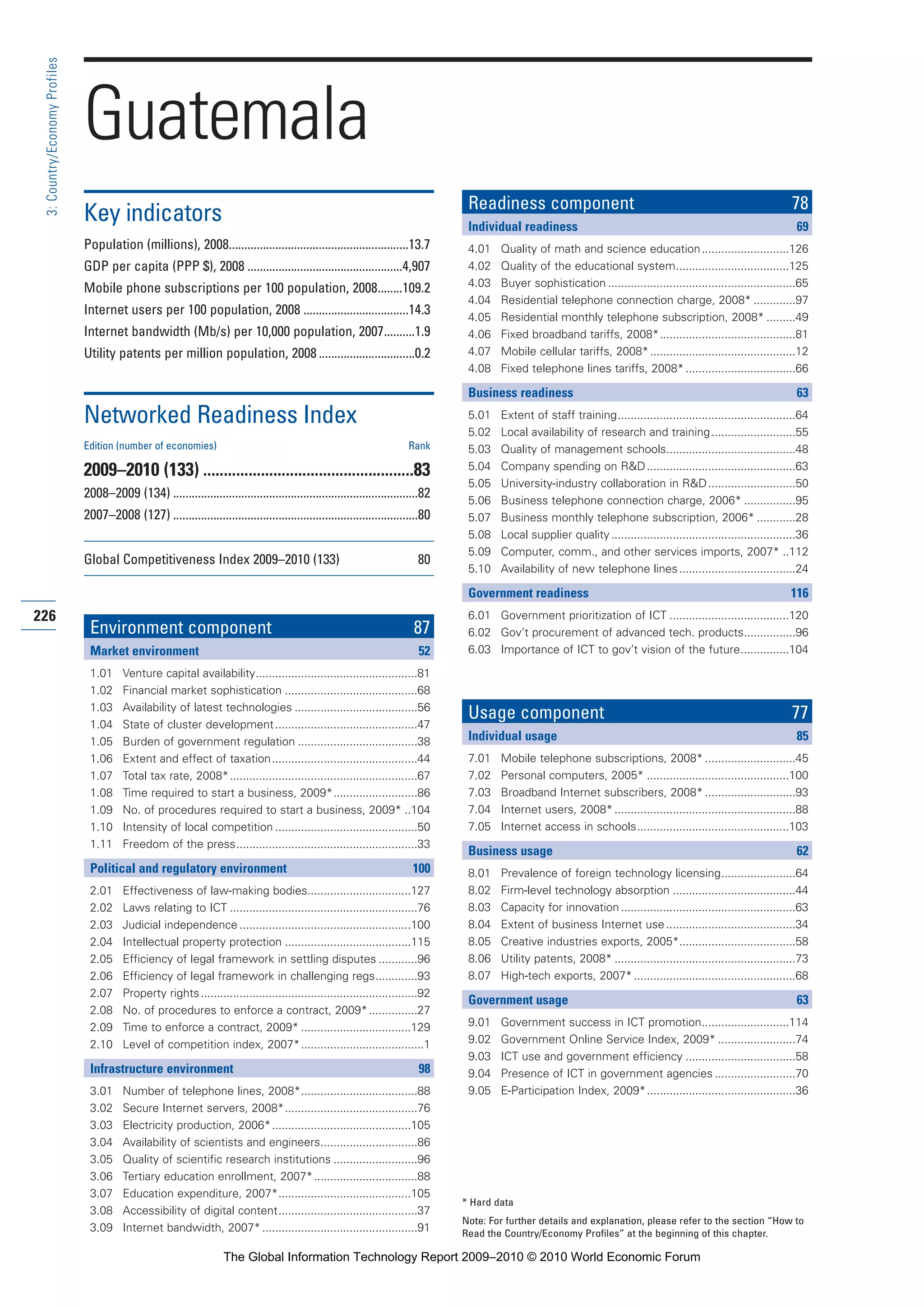

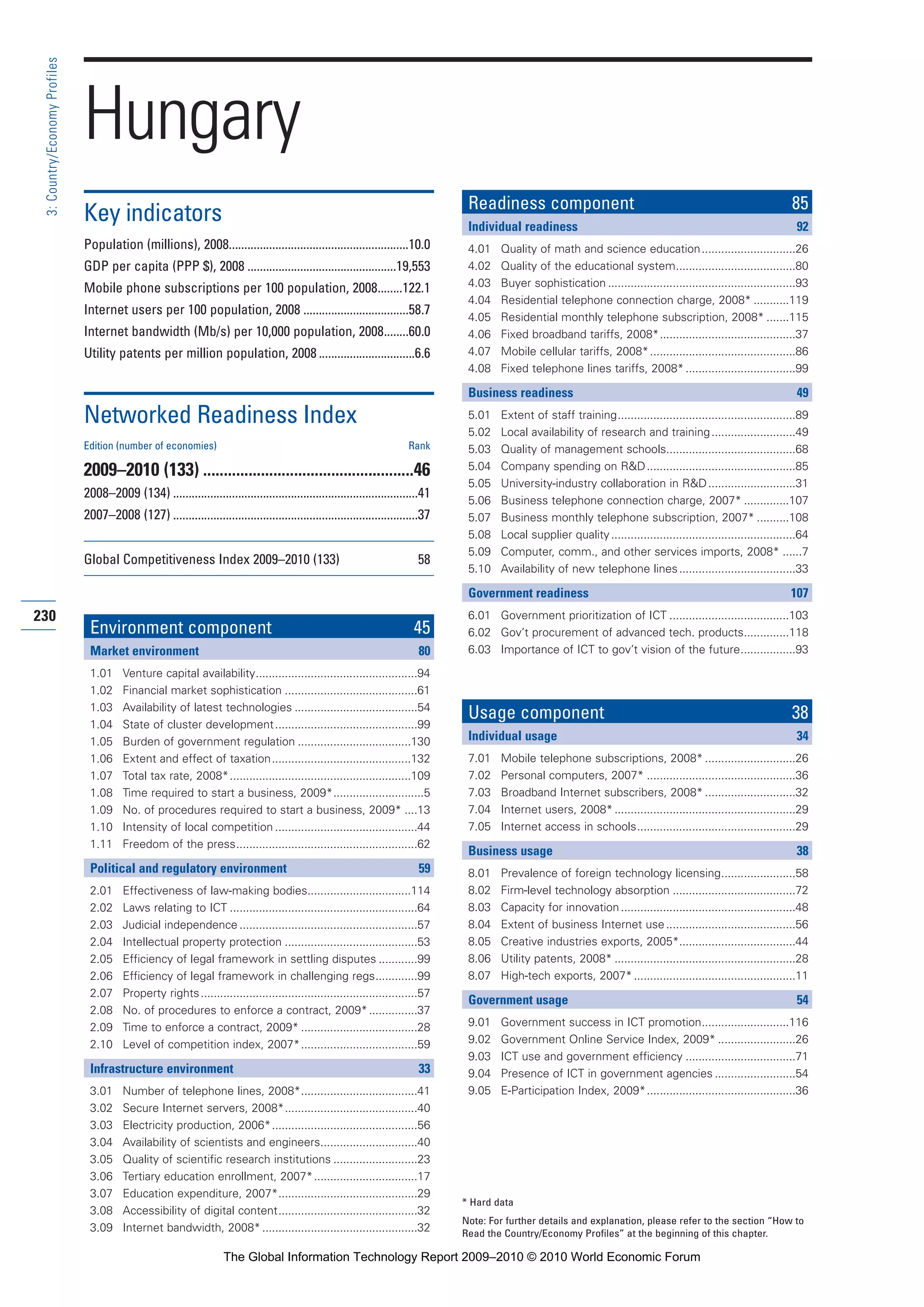

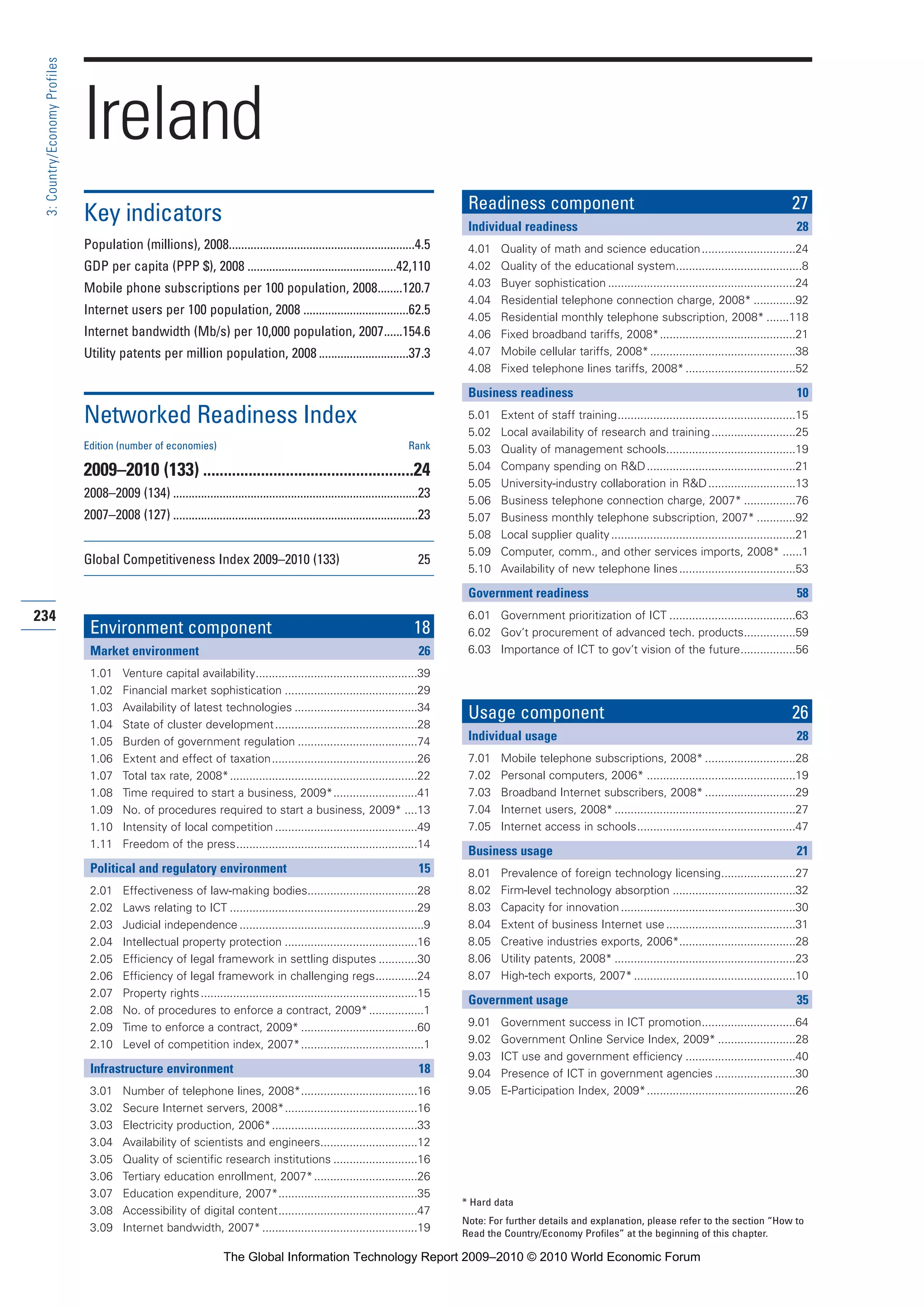

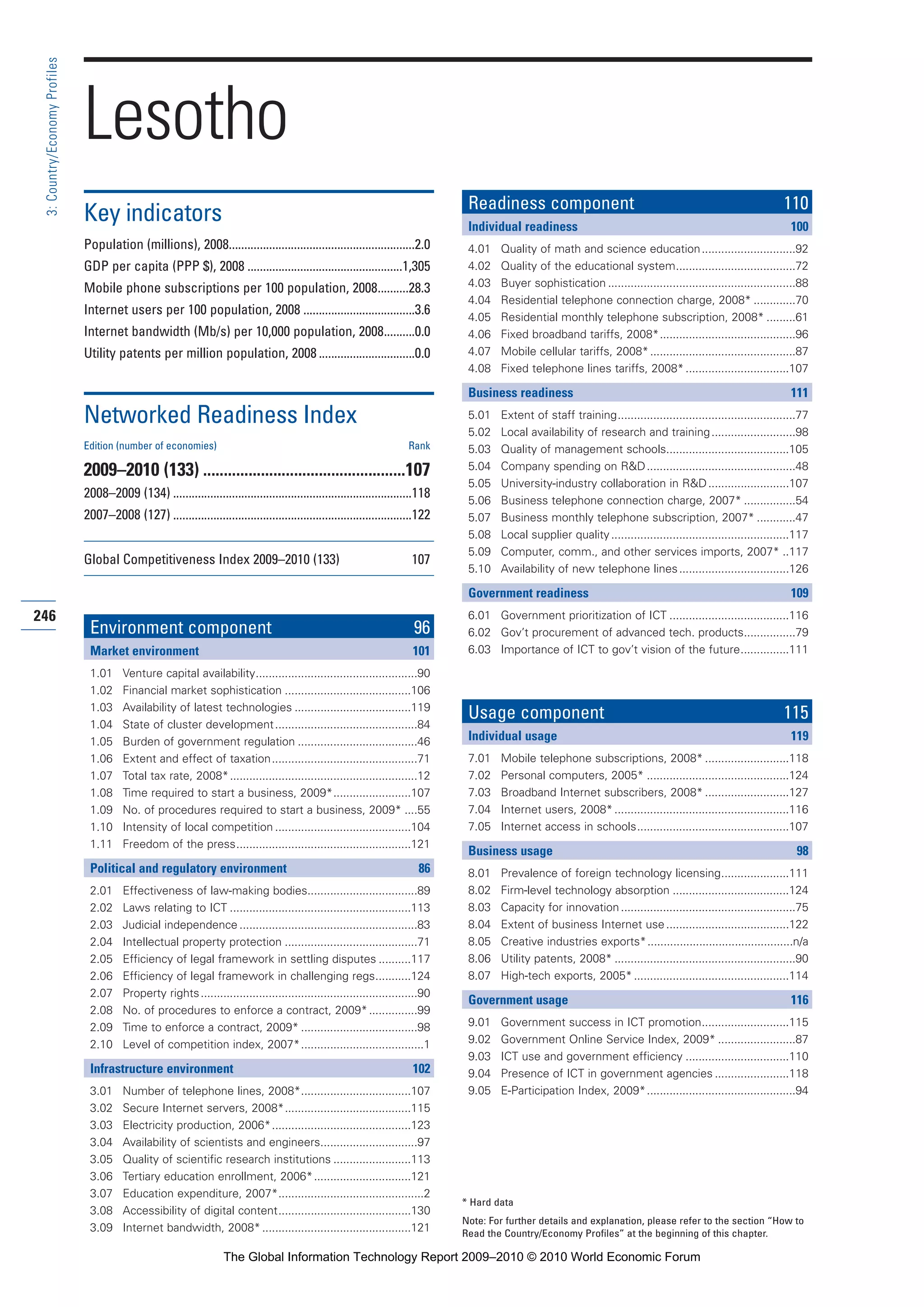

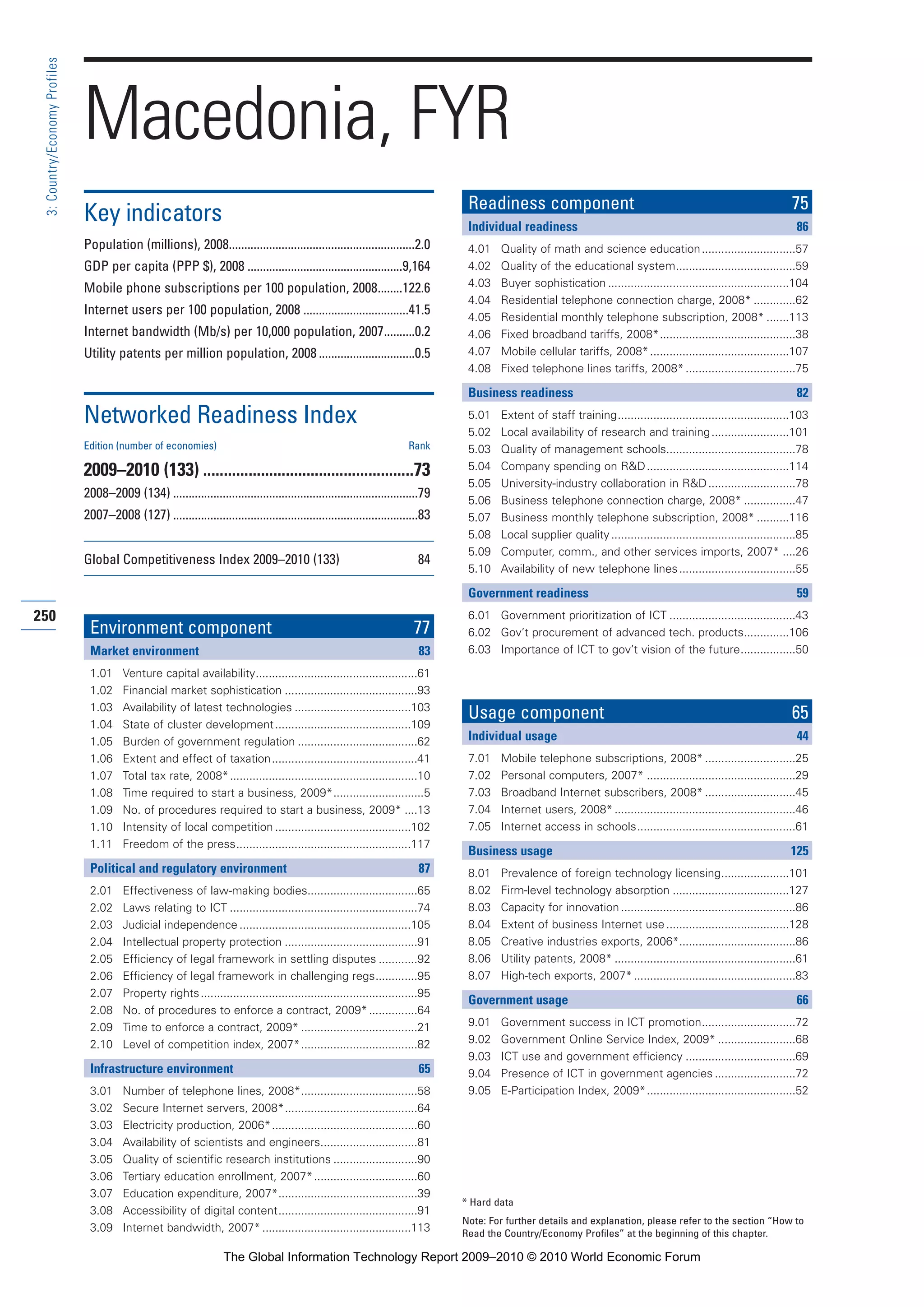

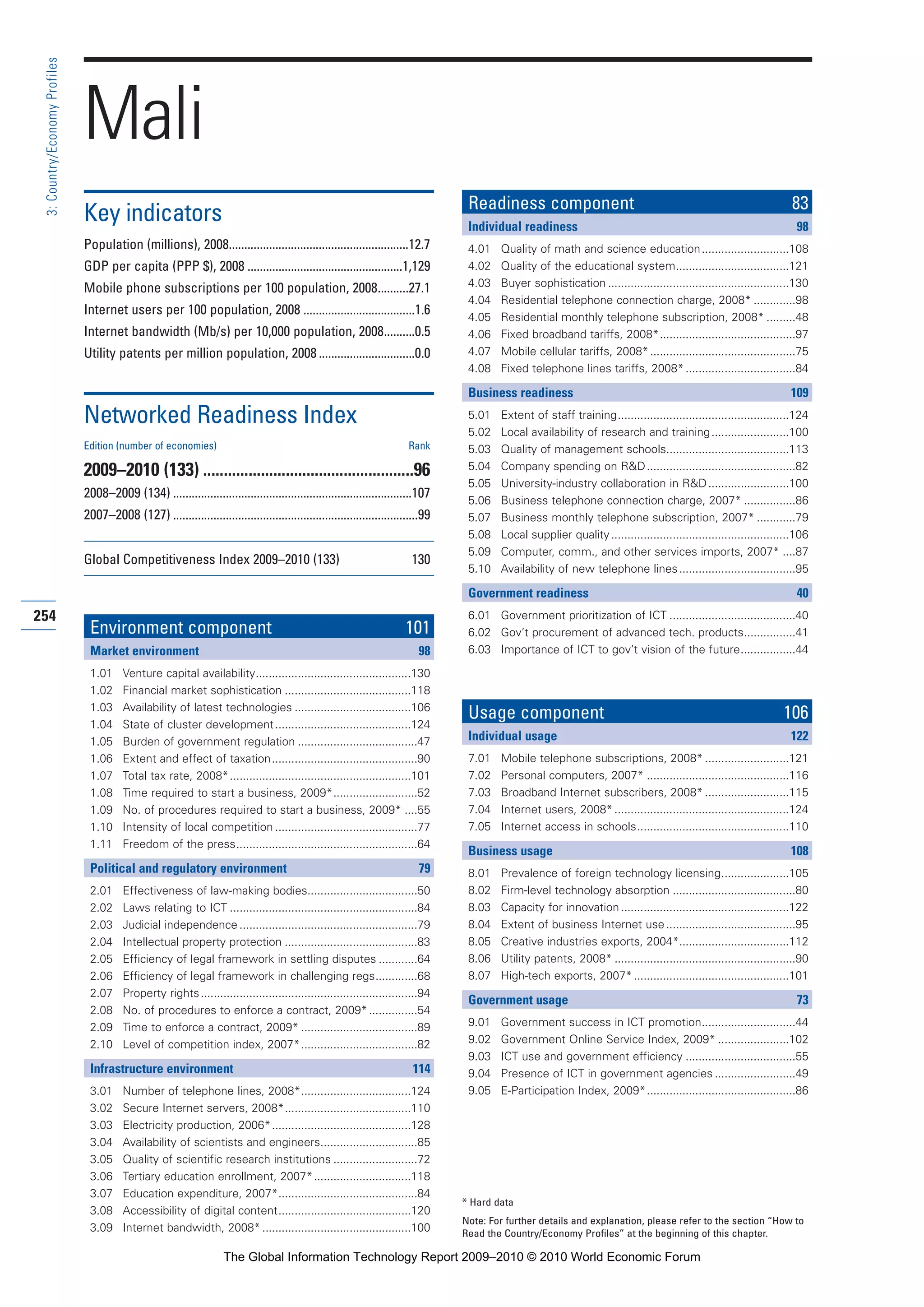

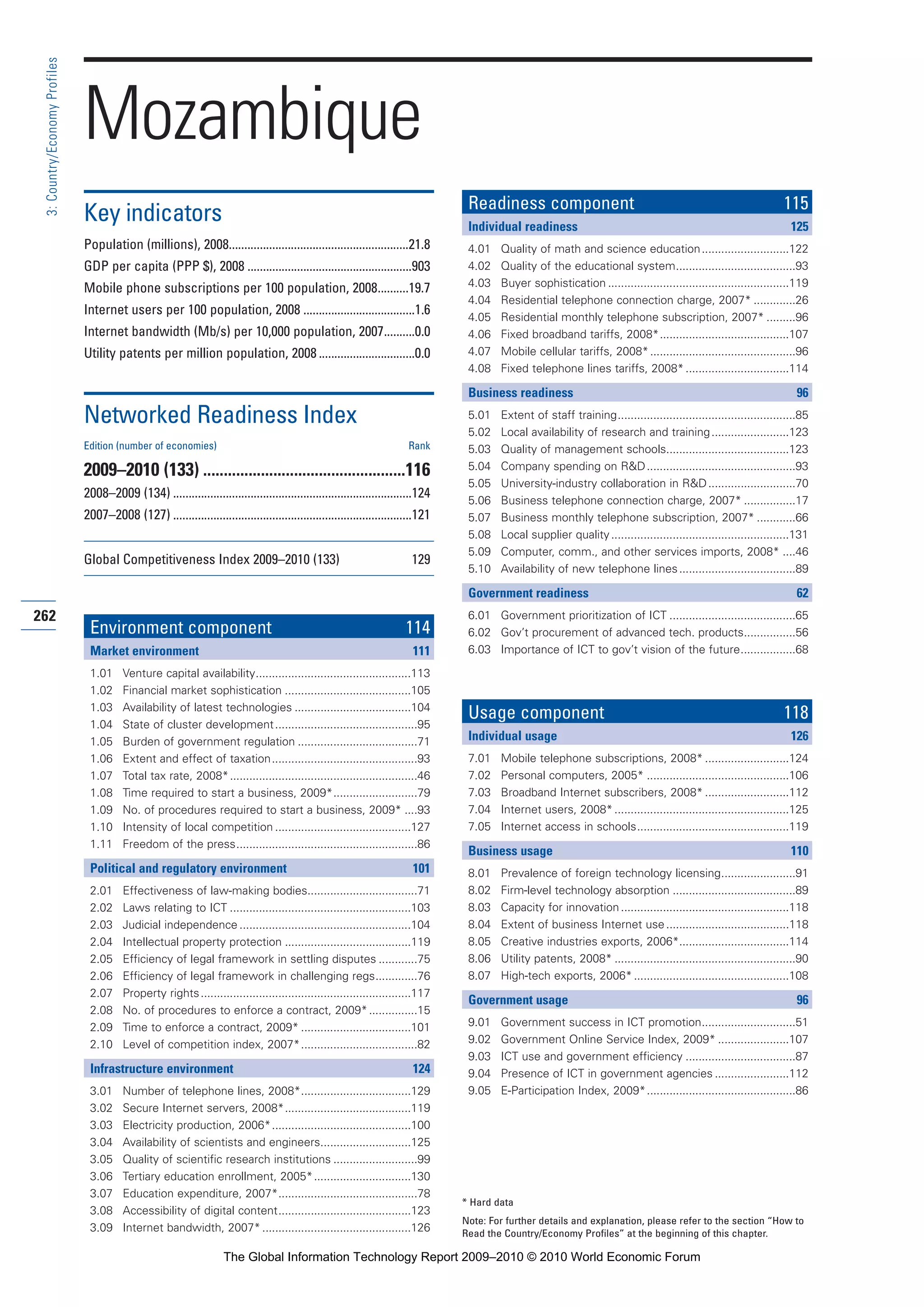

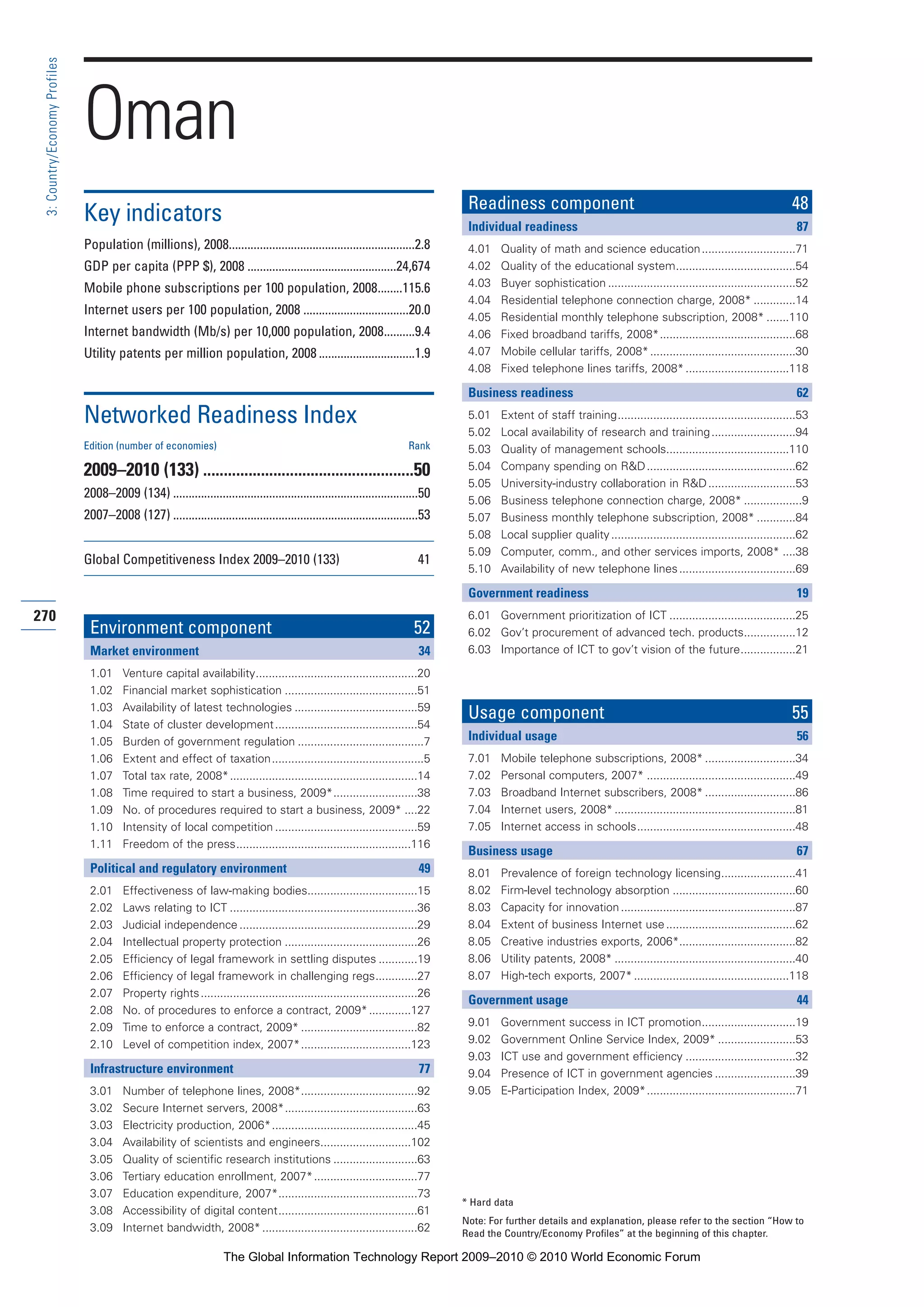

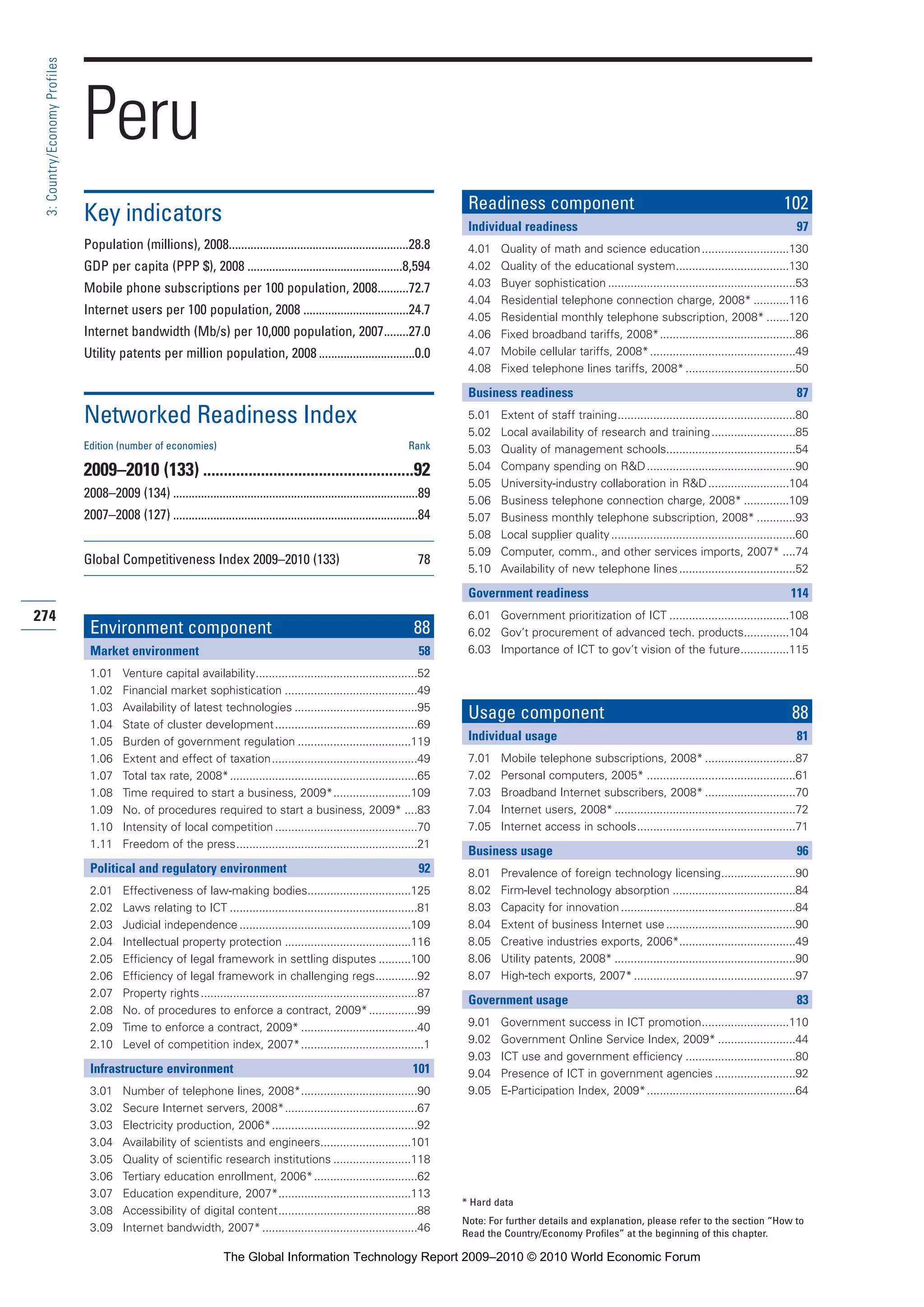

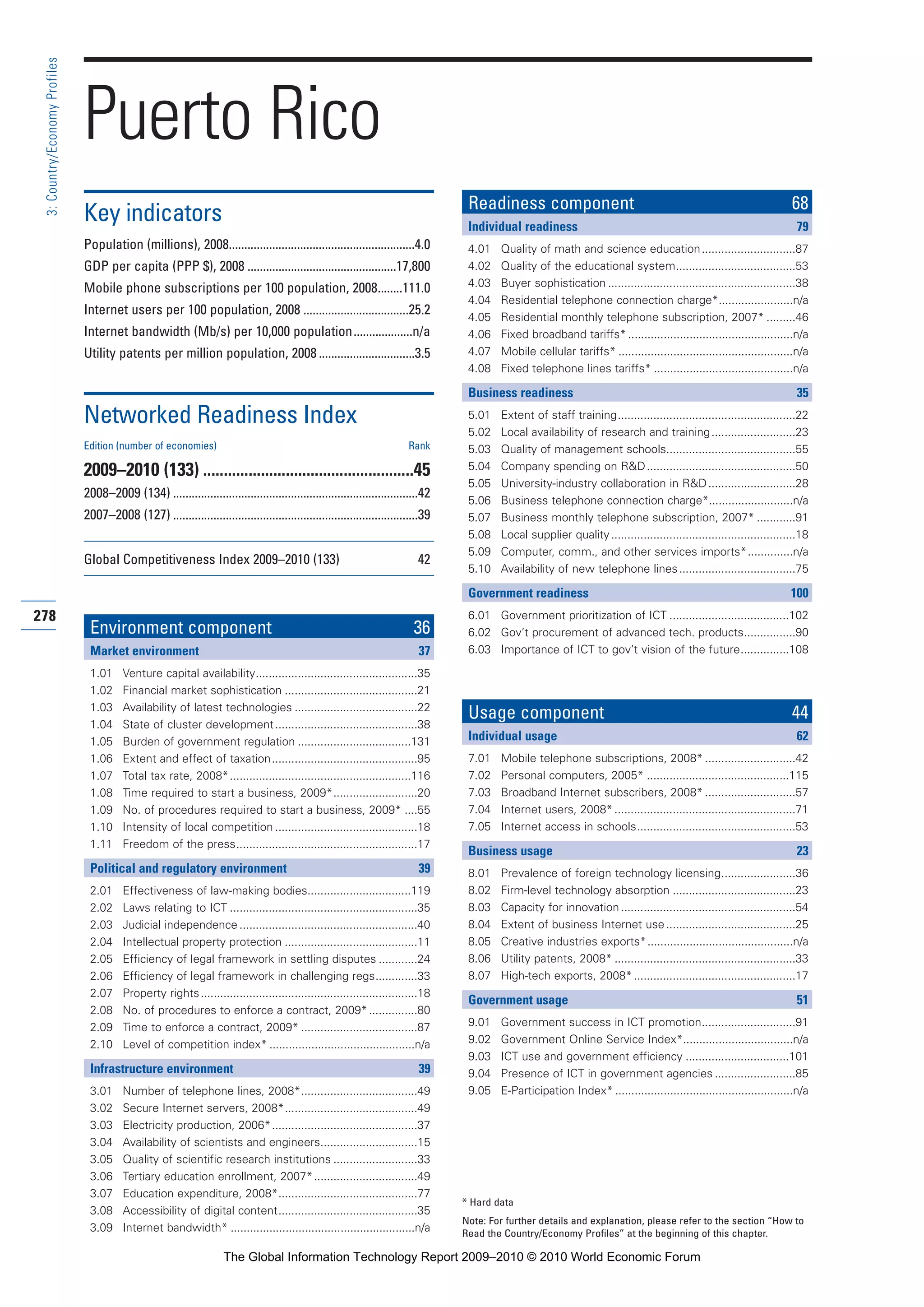

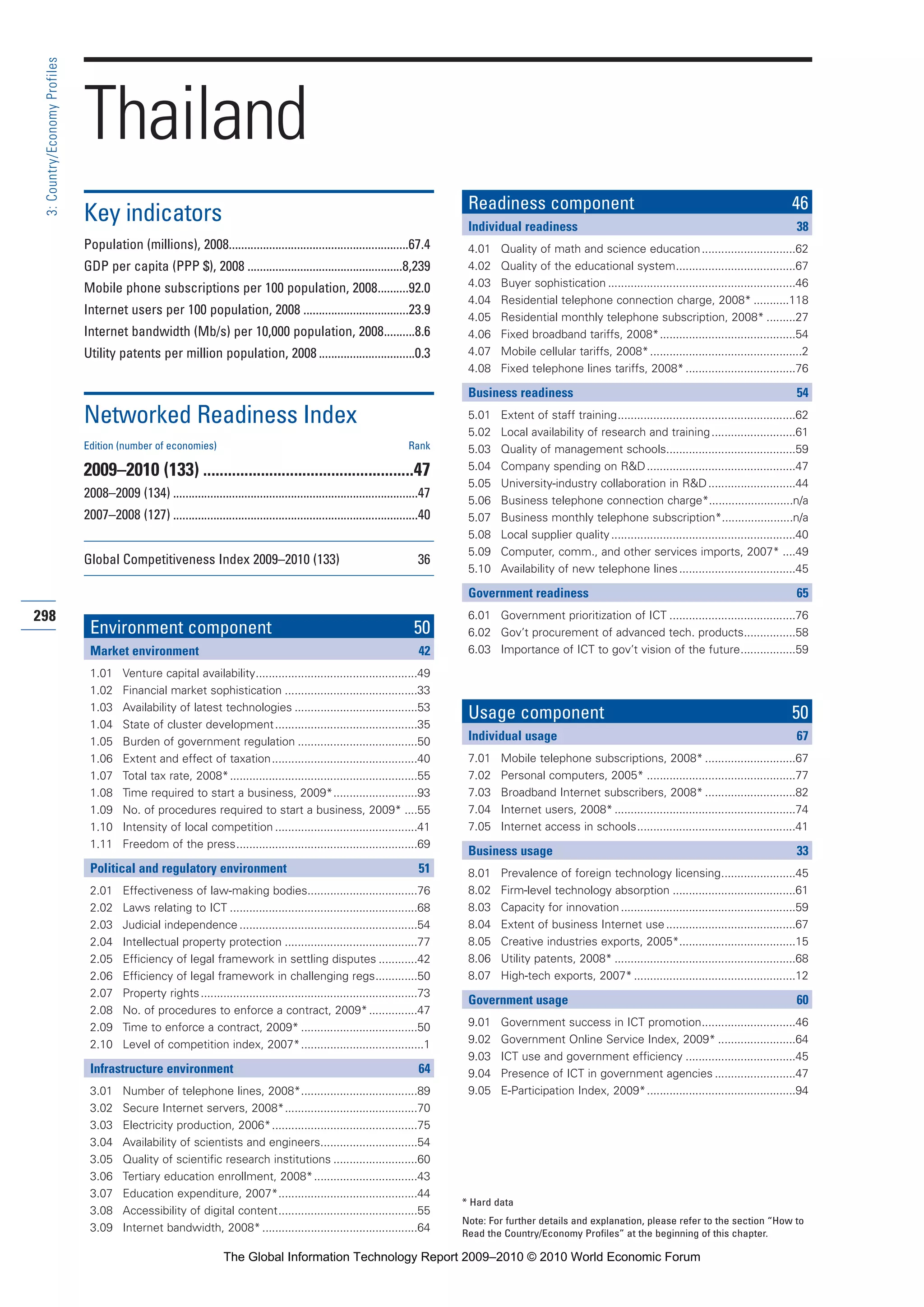

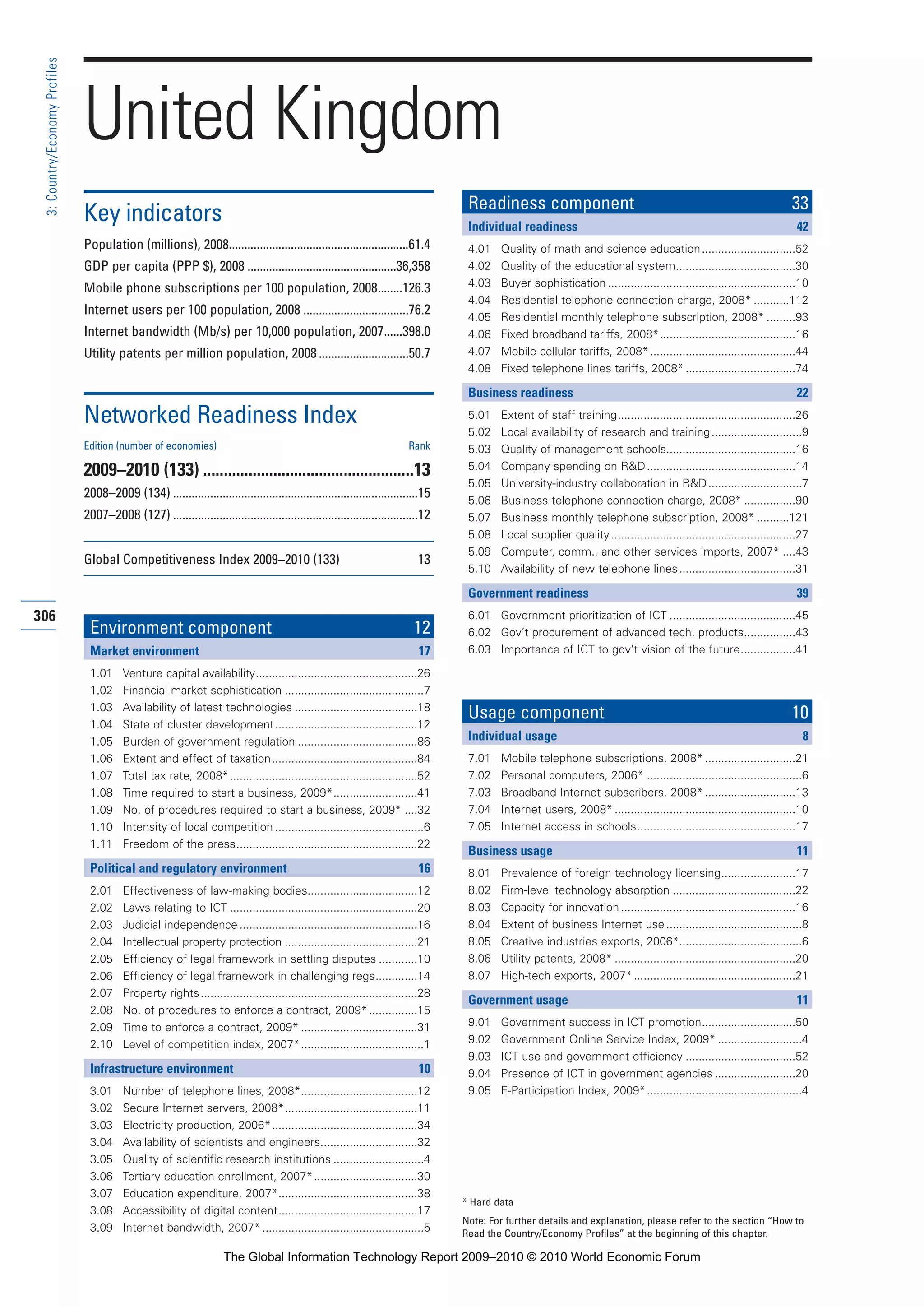

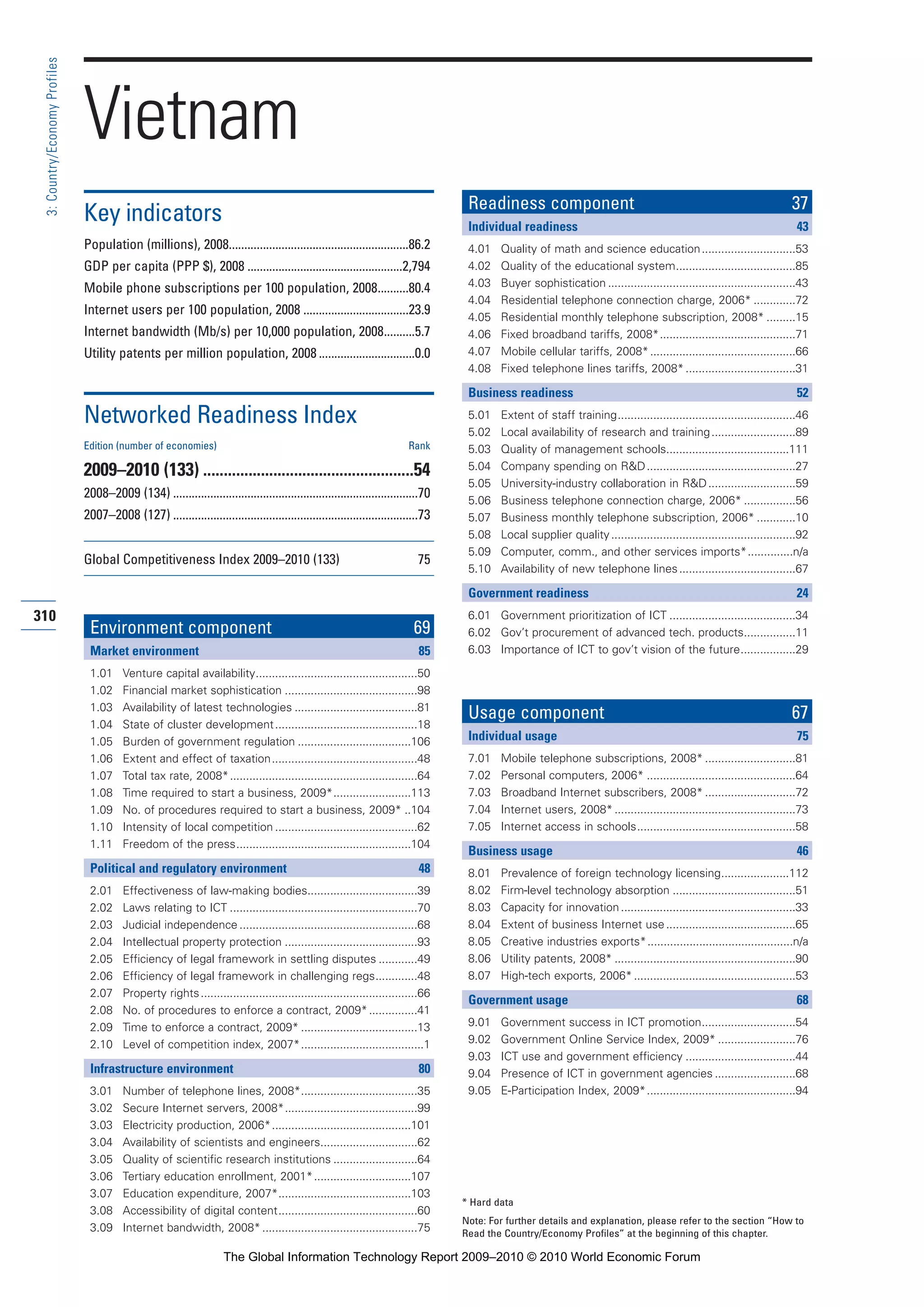

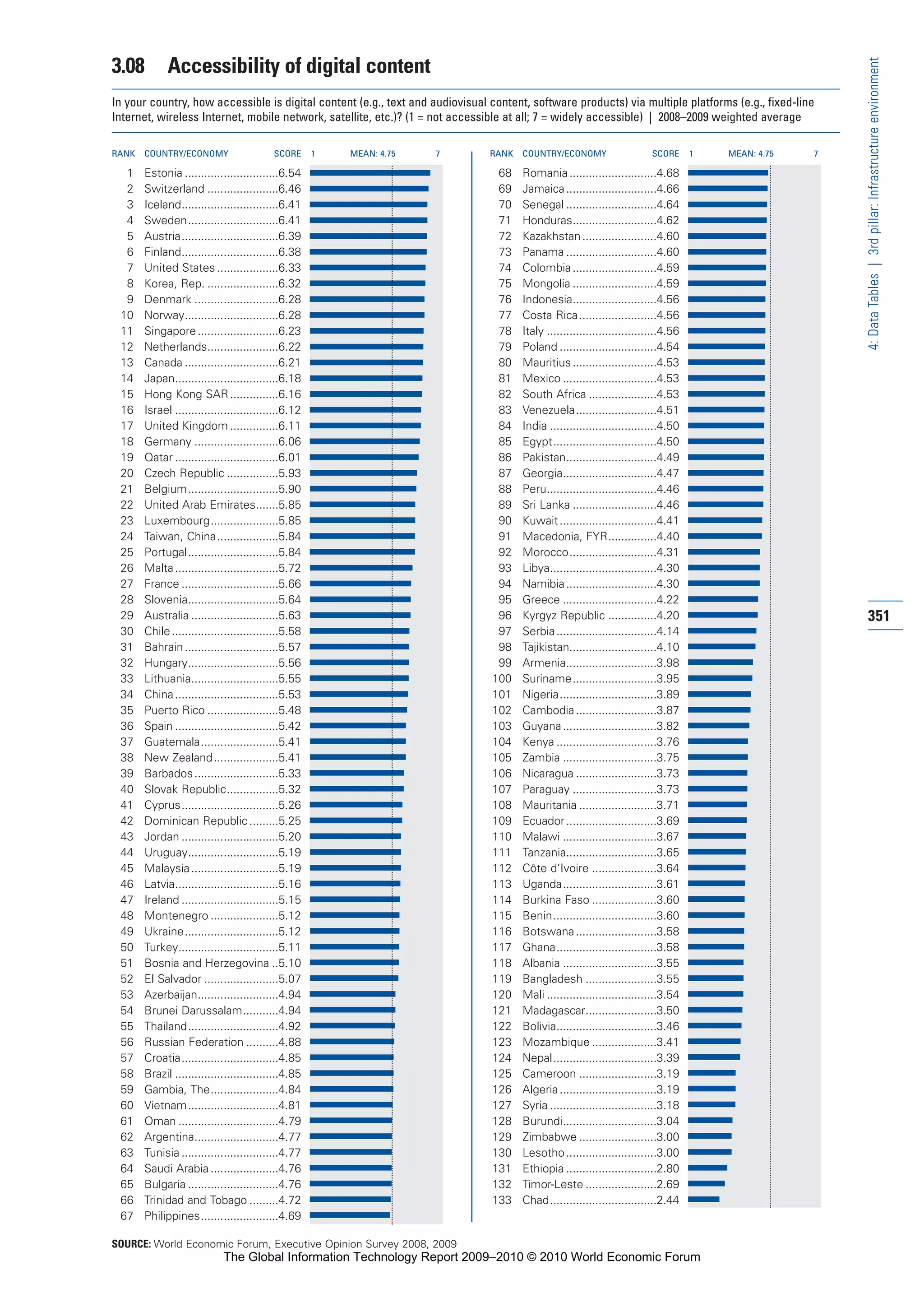

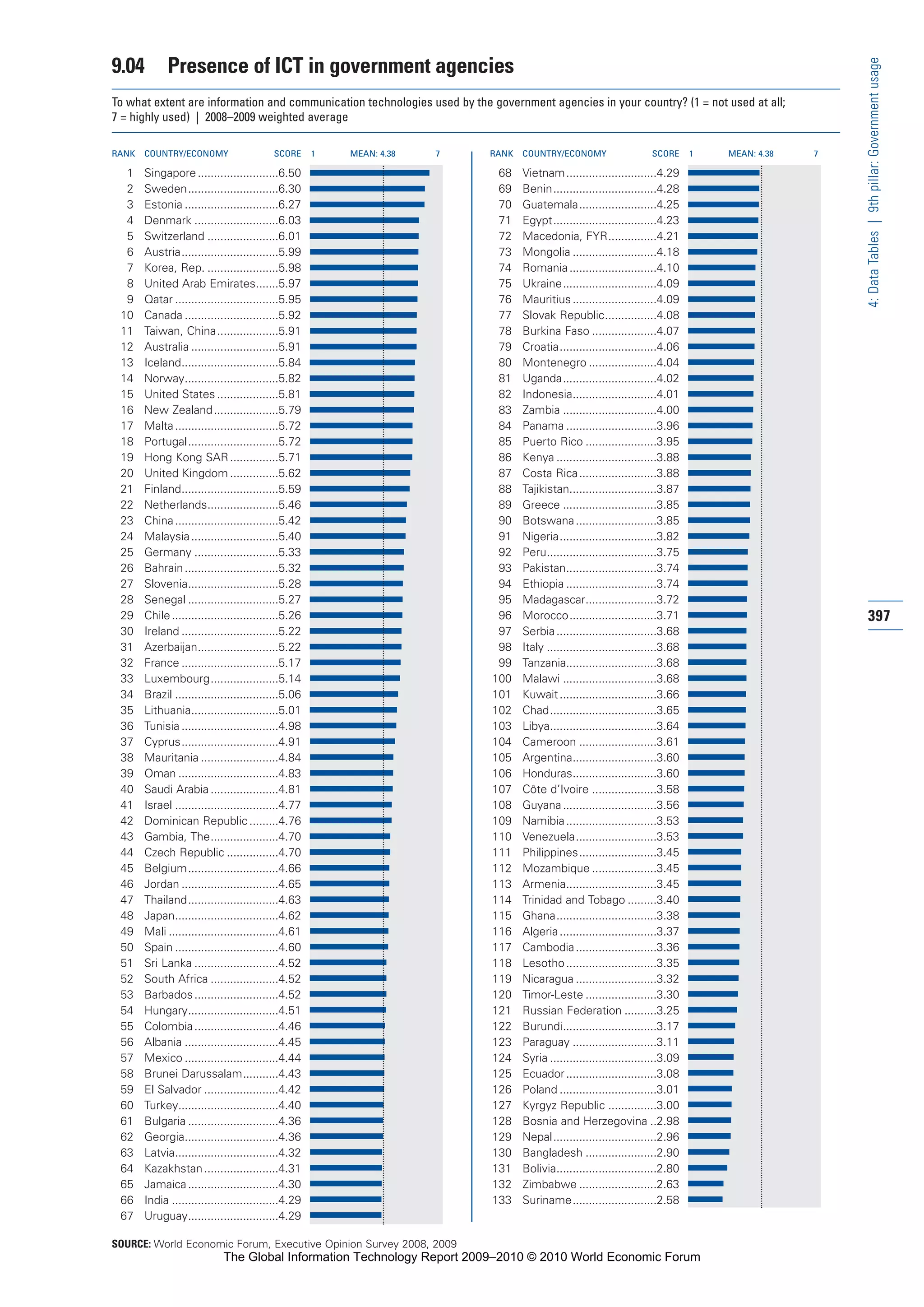

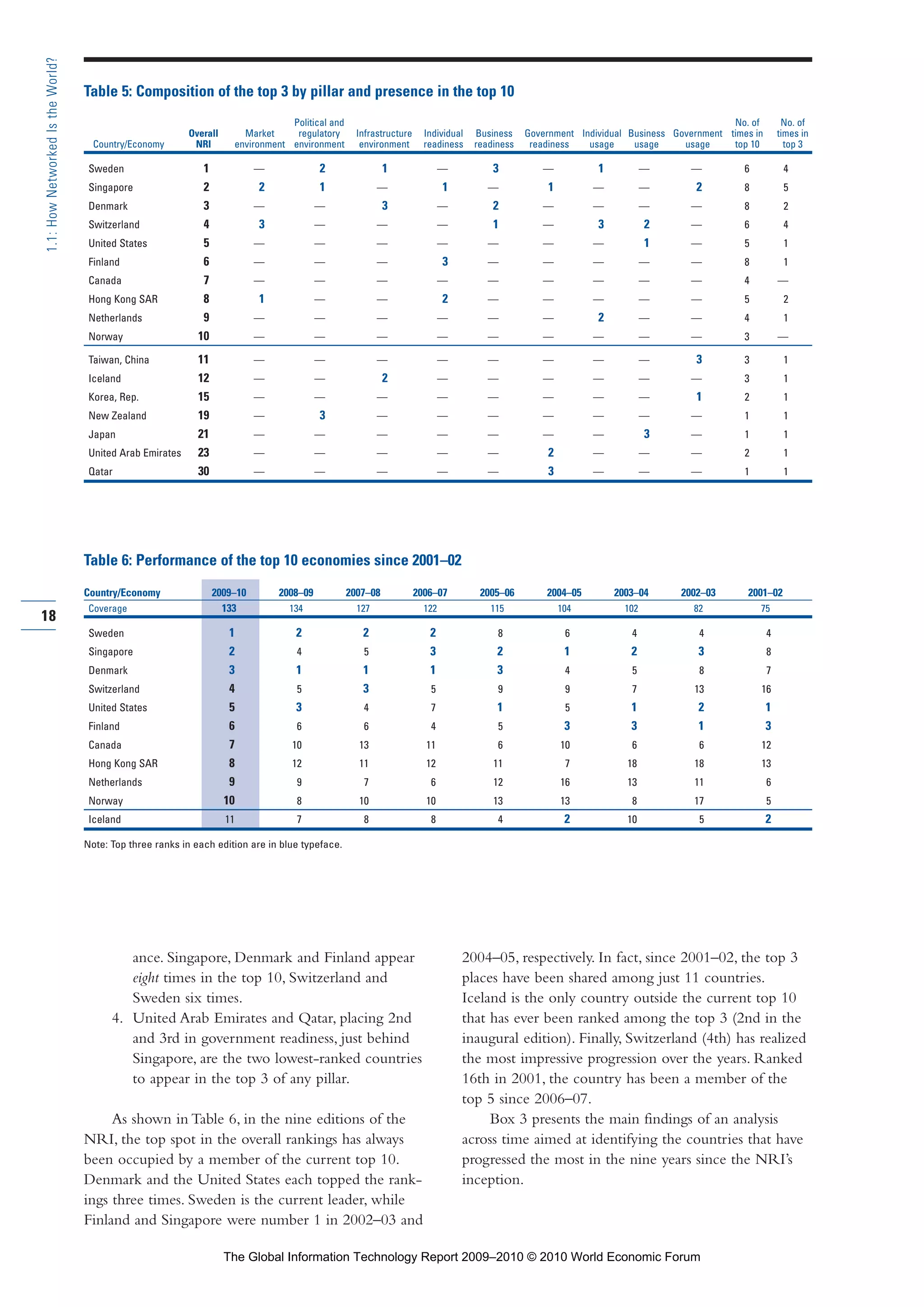

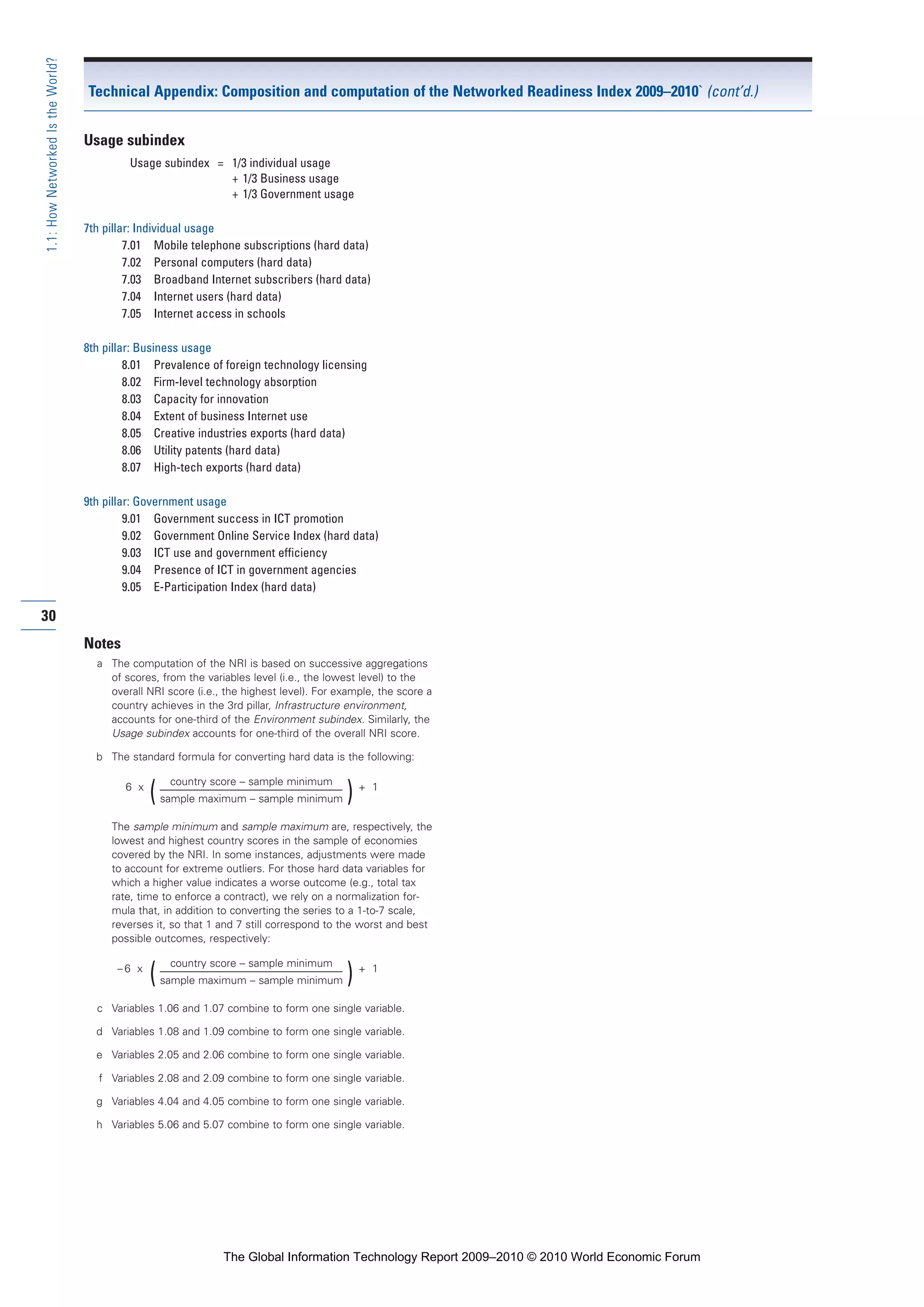

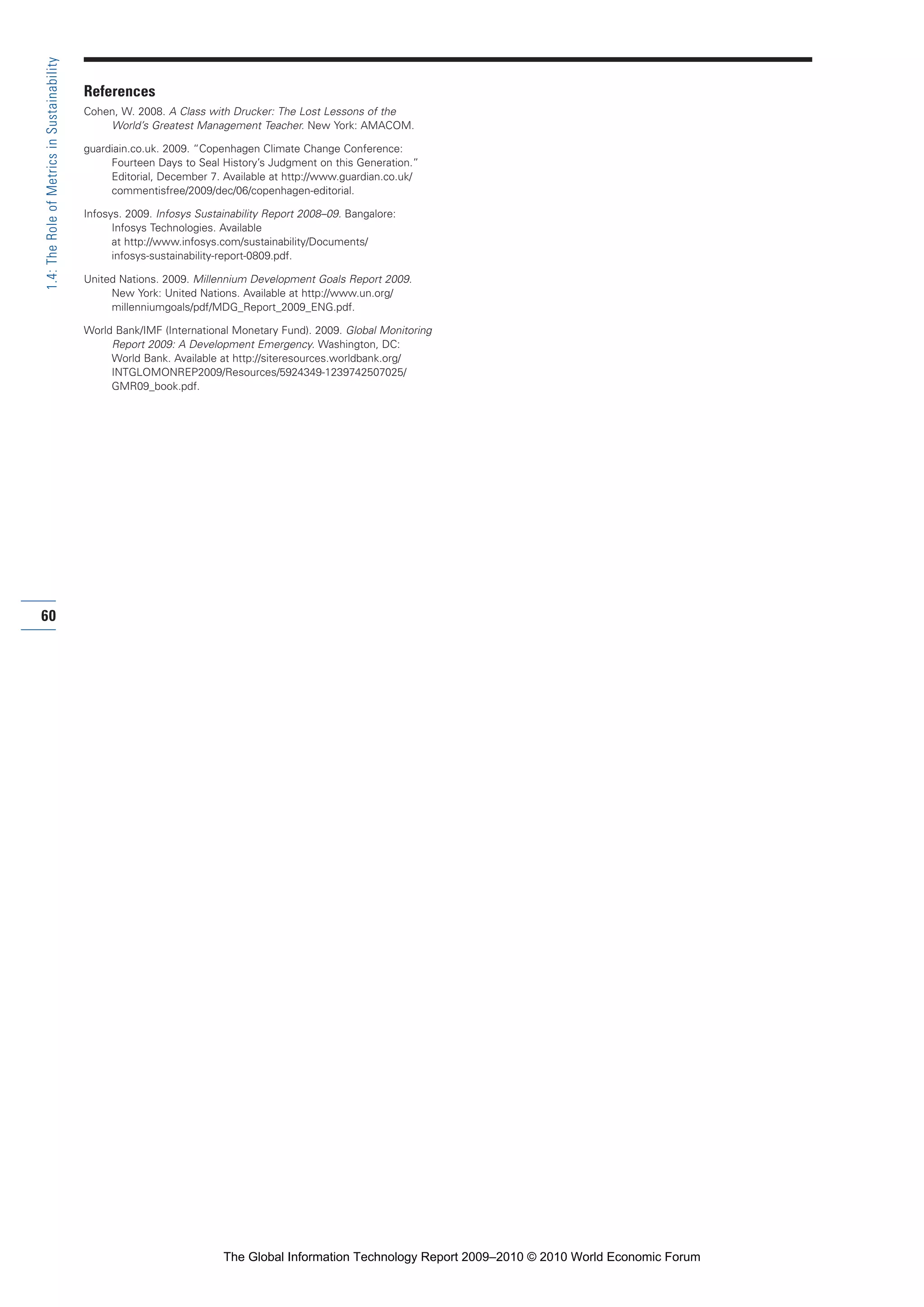

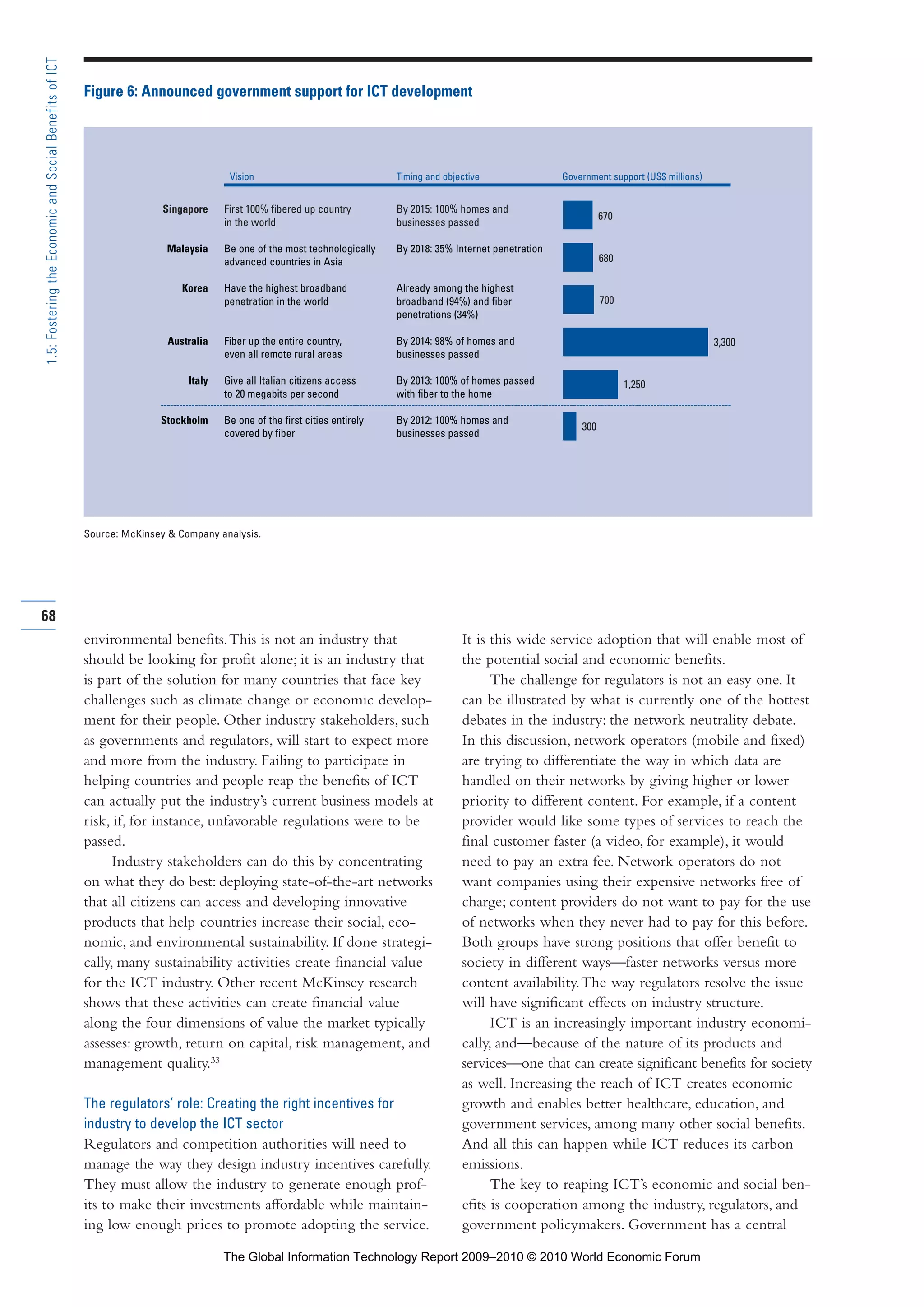

There are several aspects of a green building that

can provide significant energy savings. Every new build-

ing designed should incorporate the following design

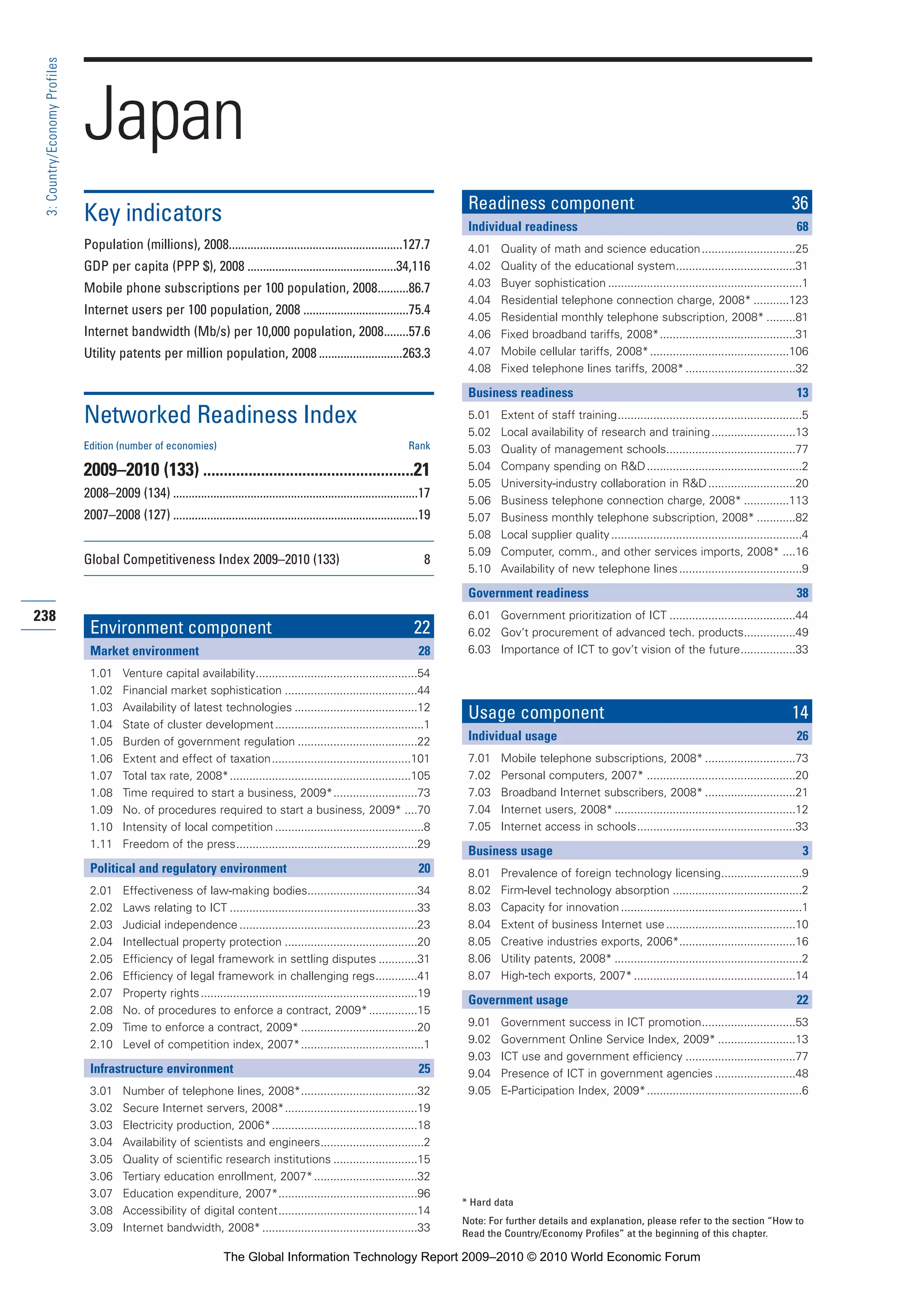

optimization processes (see Figure 1):

• optimize the building envelope to minimize the

heat entering the building;

• minimize internal heat loads such as lighting, equip-

ment (e.g., computers), and fresh air treatment.

These two steps will reduce the requirement for

air-conditioning; and

• improve further, after minimizing all the heat loads,

by efficient system design and operation sequence.

The building envelope in a green building opti-

mizes the building design process for energy efficiency.

The kind of envelope (or exterior surface) used deter-

mines the amount of heat and daylight entering the

building.This, in turn, affects the design of the lighting

system and the air-conditioning system for the building,

both of which are major energy consumers.

Building envelope optimization is realized by

designing efficient walls, roofs, and windows. Hourly

simulation software can be used to model the buildings,

predicting different scenarios of daylight, glare at differ-

ent times of the day, and heat gains into the building.

This is an iterative process, performed with various

combinations of glass and shading, to get the best com-

bination that will bring in maximum daylight and at

the same time reduce heat and glare entering the build-

ing.The shading on the windows cuts down direct radi-

ation, thereby reducing heat gains into the building and

minimizing visual glare.Technologies such as light

shelves are used to cut off direct sunlight and reflect

light deep into the office spaces.

Insulation is used for walls and roof for thermal

resistance, so that the heat coming into the building is

minimized.At Infosys’s Software Development Block-5

(SDB-5) building in its Mysore Development Center,

the walls (cavity wall with 50 millimeters [mm] extrud-

ed polystyrene insulation) have a thermal resistance five

times higher than the regular brick walls of conventional

buildings.This means the heat ingress through the walls

is five times less. Similarly, the insulated roof (RCC roof

with 75mm extruded polystyrene over-deck insulation)

provides resistance eight times that of a conventional

RCC roof.The air-conditioning requirement has been

reduced from 622 tonnage of refrigeration (TR) to 530

TR because of the efficient envelope, and thus the elec-

trical load and energy consumption of the building fell

correspondingly.

The next major heat source is fresh air provided to

the building’s air-conditioning system.About 85 percent

57

1.4:TheRoleofMetricsinSustainability

Building envelope

(wall, roof, window)

Lighting

Heating, ventilation,

and air conditioning

Building total

Figure 1: Design optimization process

Part 1.r2 3/2/10 4:40 AM Page 57

The Global Information Technology Report 2009–2010 © 2010 World Economic Forum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cusersdesktop2010gitr2009-2010fullreportfinal-100402152331-phpapp01/75/The-Global-Information-Technology-Report-2009-2010-77-2048.jpg)

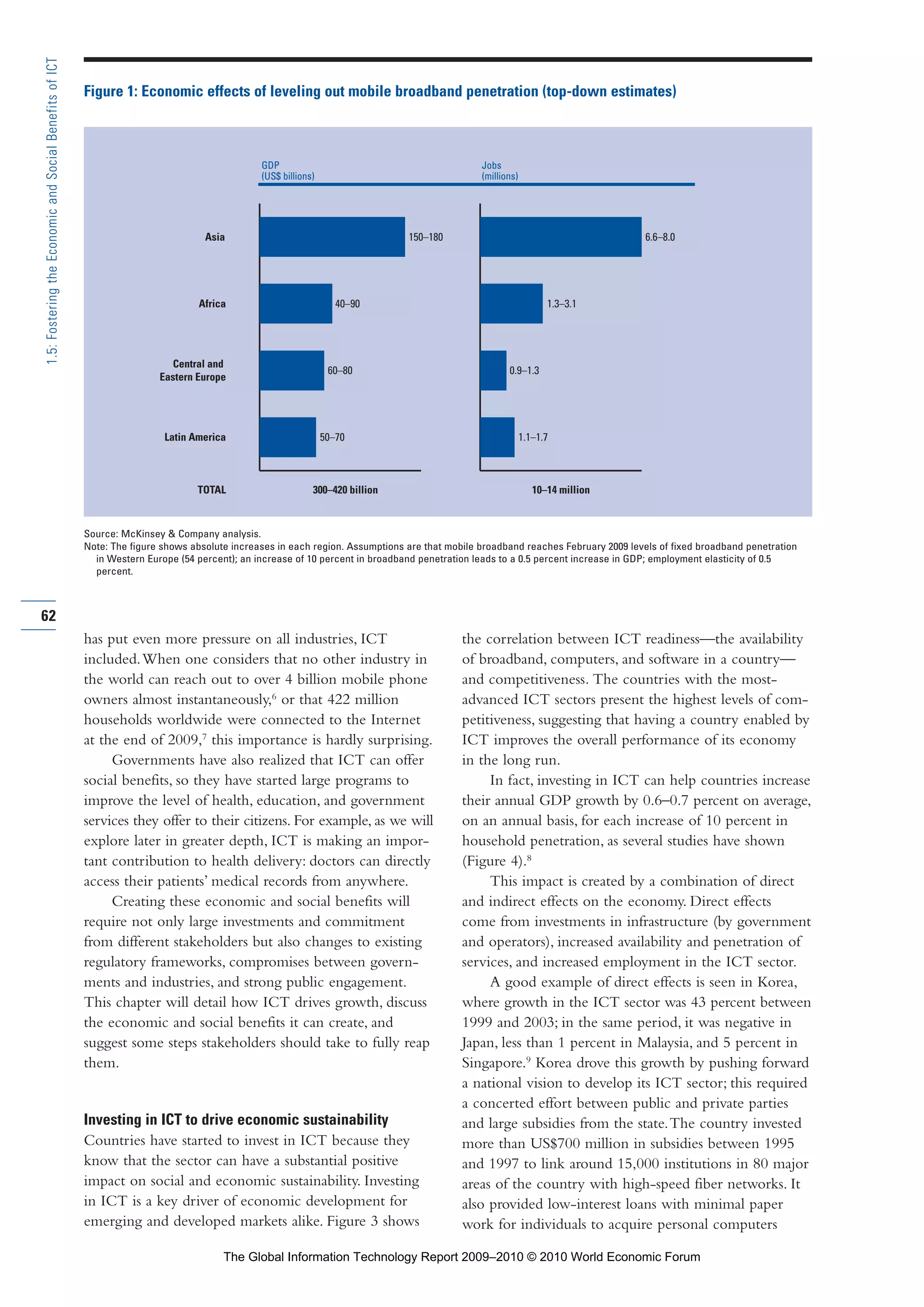

![themselves and family members (e.g., birth, marriage,

and death certificates) dating back to the 1880s. Benefits

for governments that are offering these types of services

are huge.“As recent research shows,” noted

Eurochambres Secretary-General Arnaldo Abruzzini in

November 2009,“electronic procedures will lead to

more bidders and thus increased competition, which

could create savings in the order of 150 billion EU-

wide.”22

Improving information access and communications

ICT is changing the way people access information

(with Google and Wikipedia, for example) and interact

with each other (through blogs, social

networking sites, virtual reality sites, and so forth).

Social networking websites have changed the job

recruitment rules.Today these sites are the places to find

a job and recruit talent.A recent survey, conducted in

May 2009, revealed that 72 percent of US companies

plan to increase their use of social network recruiting.

Ninety-five percent of companies used LinkedIn;

Facebook use by companies grew from 36 percent in

2008 to 59 percent in 2009.23

Interestingly, it also seems

that employers are more satisfied with the quality of

candidates from employee referrals and social networks

than of those from job boards. From the candidate’s

point of view, a recent survey showed that today 6 per-

cent of respondents found their last job via a social net-

working site—which is fairly high when one takes into

account that these websites started to acquire a critical

mass only a few years ago.24

It seems likely that such

sources for job hunting and recruiting will only grow in

importance given their overall growth in use.

The latest presidential election in the United States

heavily leveraged these types of social networking

websites. Internet users could have a connection with

then-Senator Obama on more than 15 social network-

ing sites,25

meaning that regardless of Internet users’

preferences, all of them could connect with Obama’s

pages. For instance, on Facebook, the largest group of

Obama’s supporters is composed of 1 million people,

the Obama MySpace page currently has 1.9 million

friends,26

and Obama has 3.1 million followers on

Twitter.27

He also created his own social network web-

site, MyBarackObama.com, where 2 million profiles

were created.28

The large network created by online

channels allowed Obama to reach out to people who

had not been involved in politics before and would have

not been involved otherwise.

The power of the change generated by social net-

works was also evident when a 25-year-old Moldovan

woman put a message in Twitter after she and her six

other friends were discussing doing something about

the recent—and allegedly fraudulent—parliamentary

elections.This message created a demonstration that

raided the parliament and pushed the Moldovan presi-

dent to order a recount of the recently held elections.

Speaking about the power of Twitter, the woman said

“we expected at the most a couple of hundred friends,

friends of friends, and colleagues […] when we went to

the square, there were 20,000 people waiting there. It

was unbelievable.”29

All these examples show new ways in which inno-

vative ICT technologies are having a profound impact

on the way people interact and communicate with each

other. Many of these technologies will undoubtedly lead

to new social benefits.

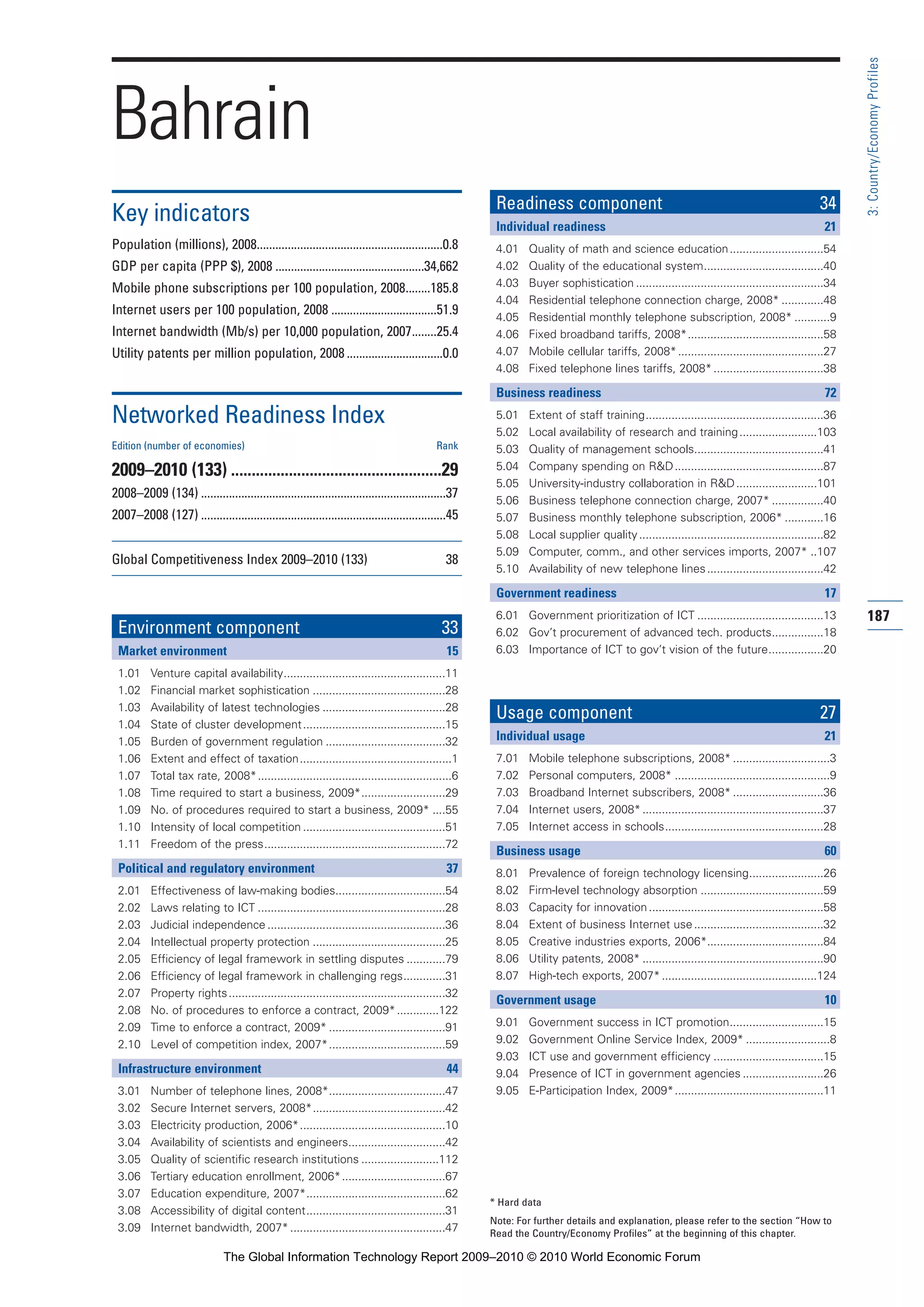

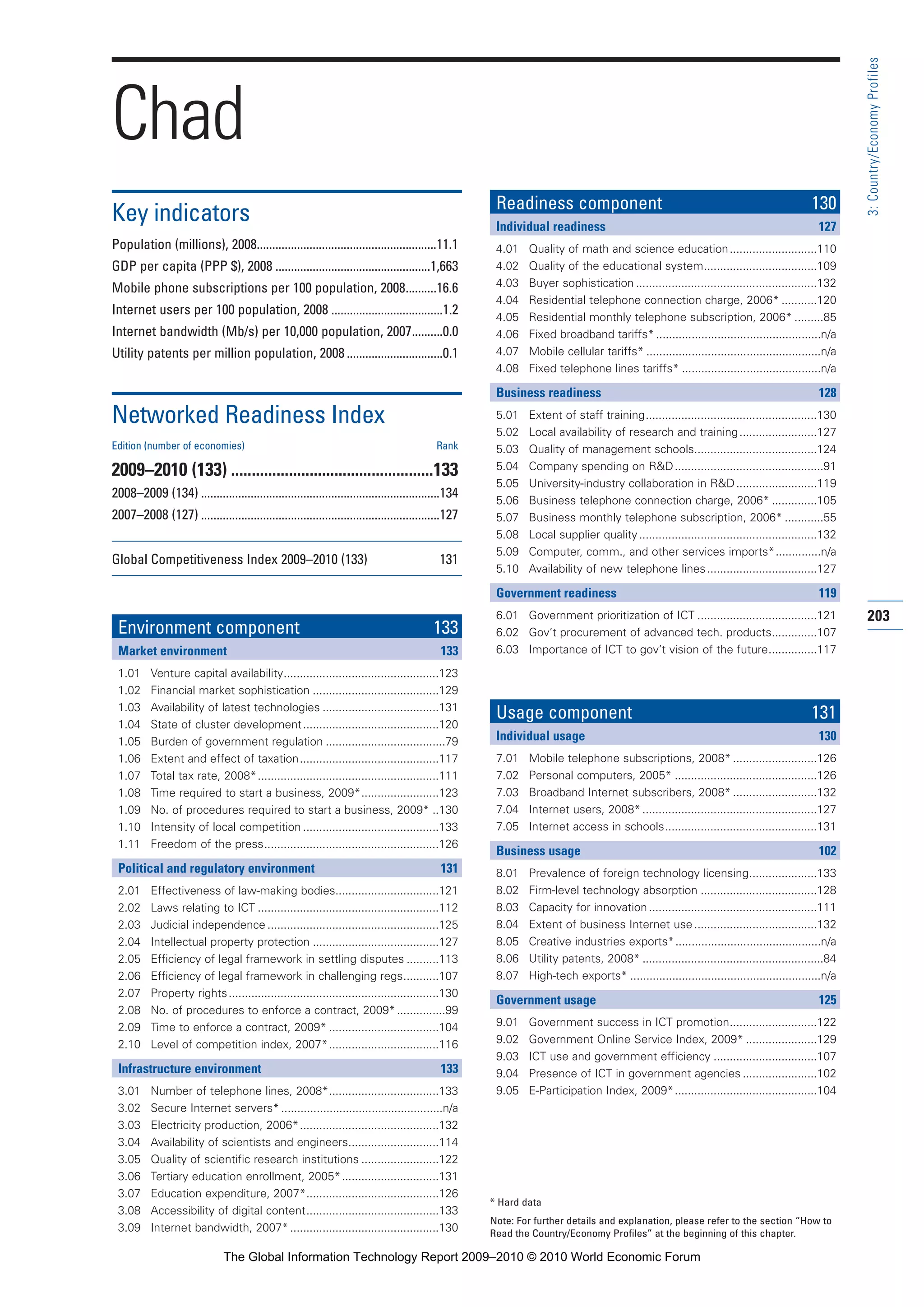

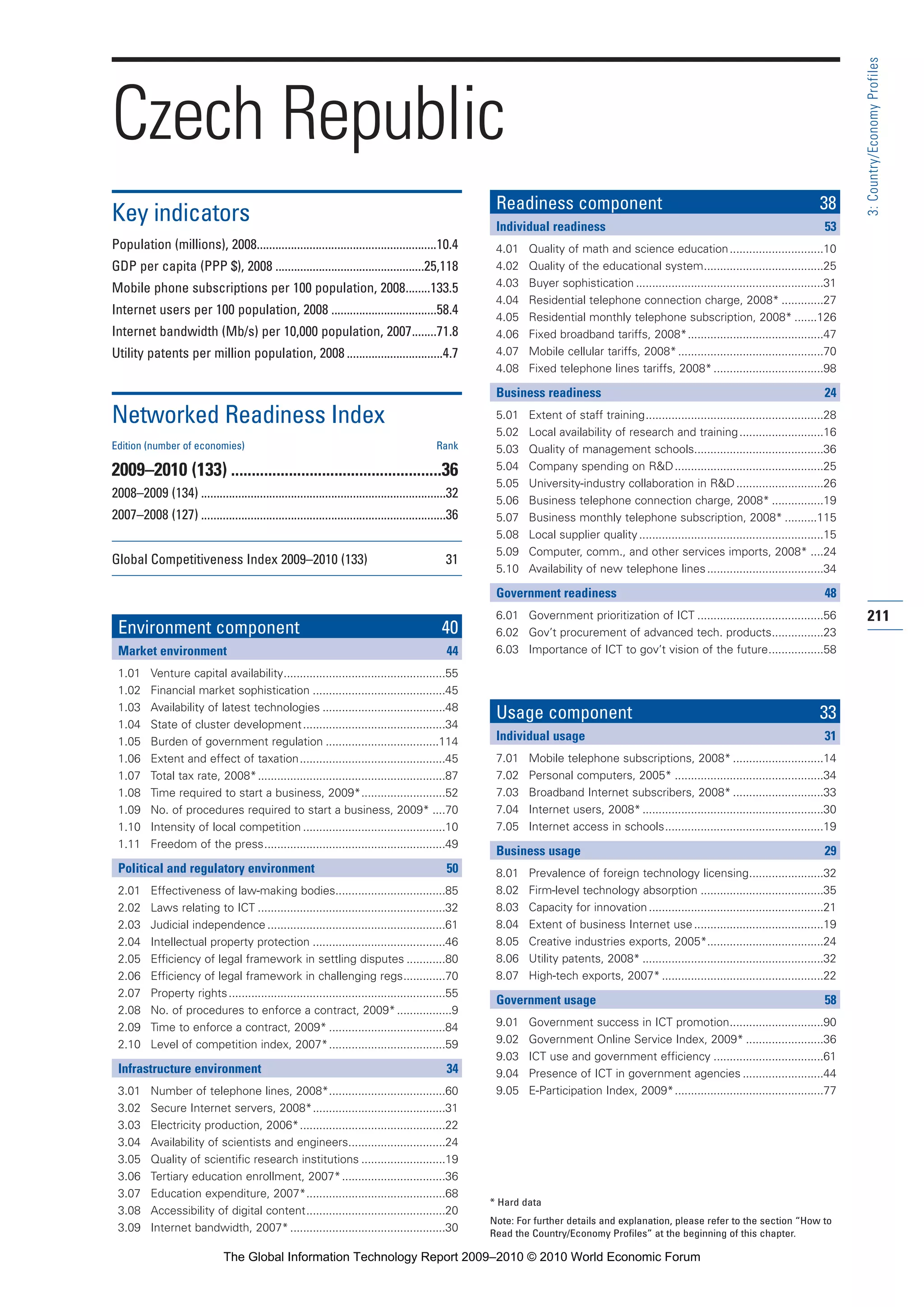

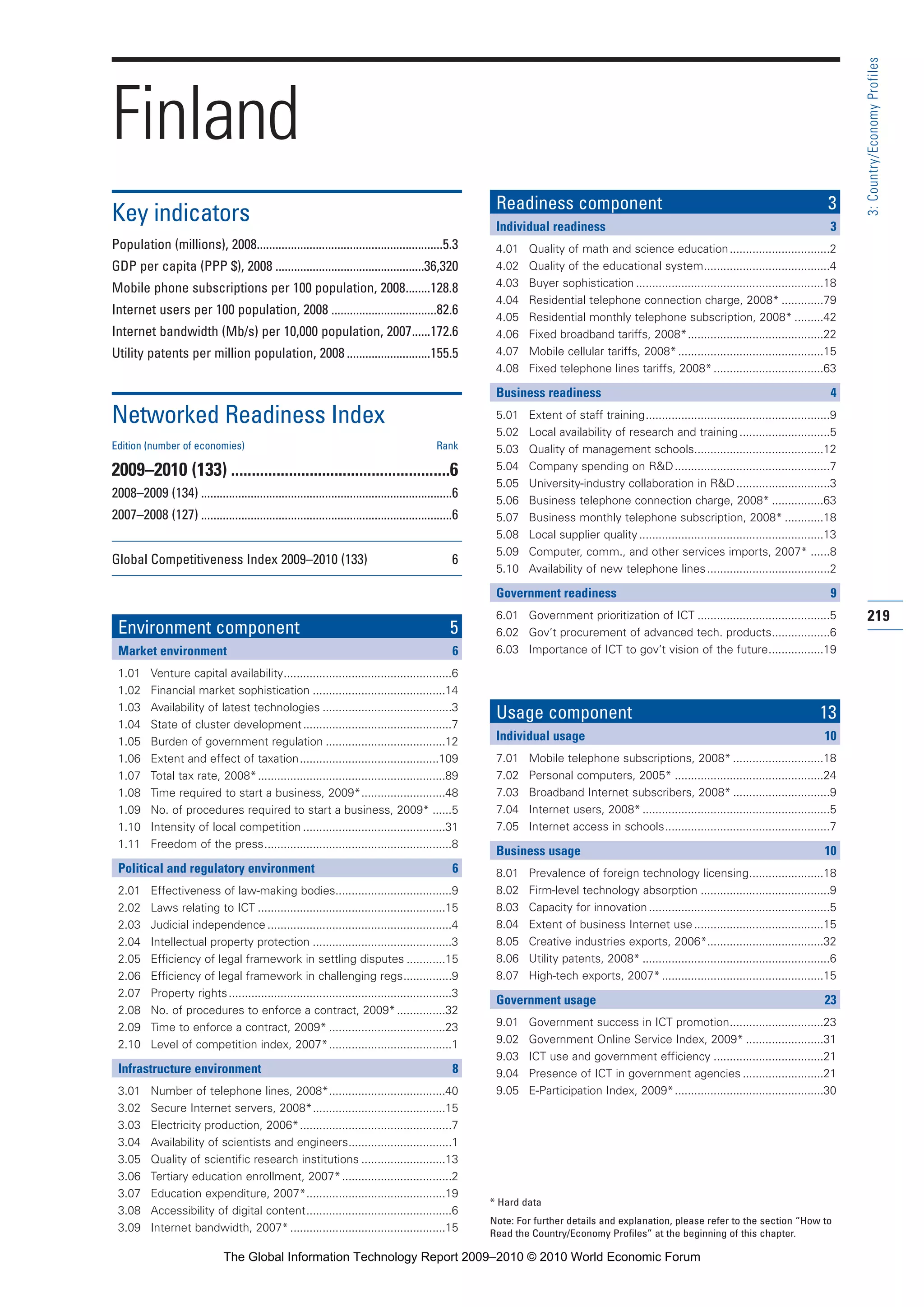

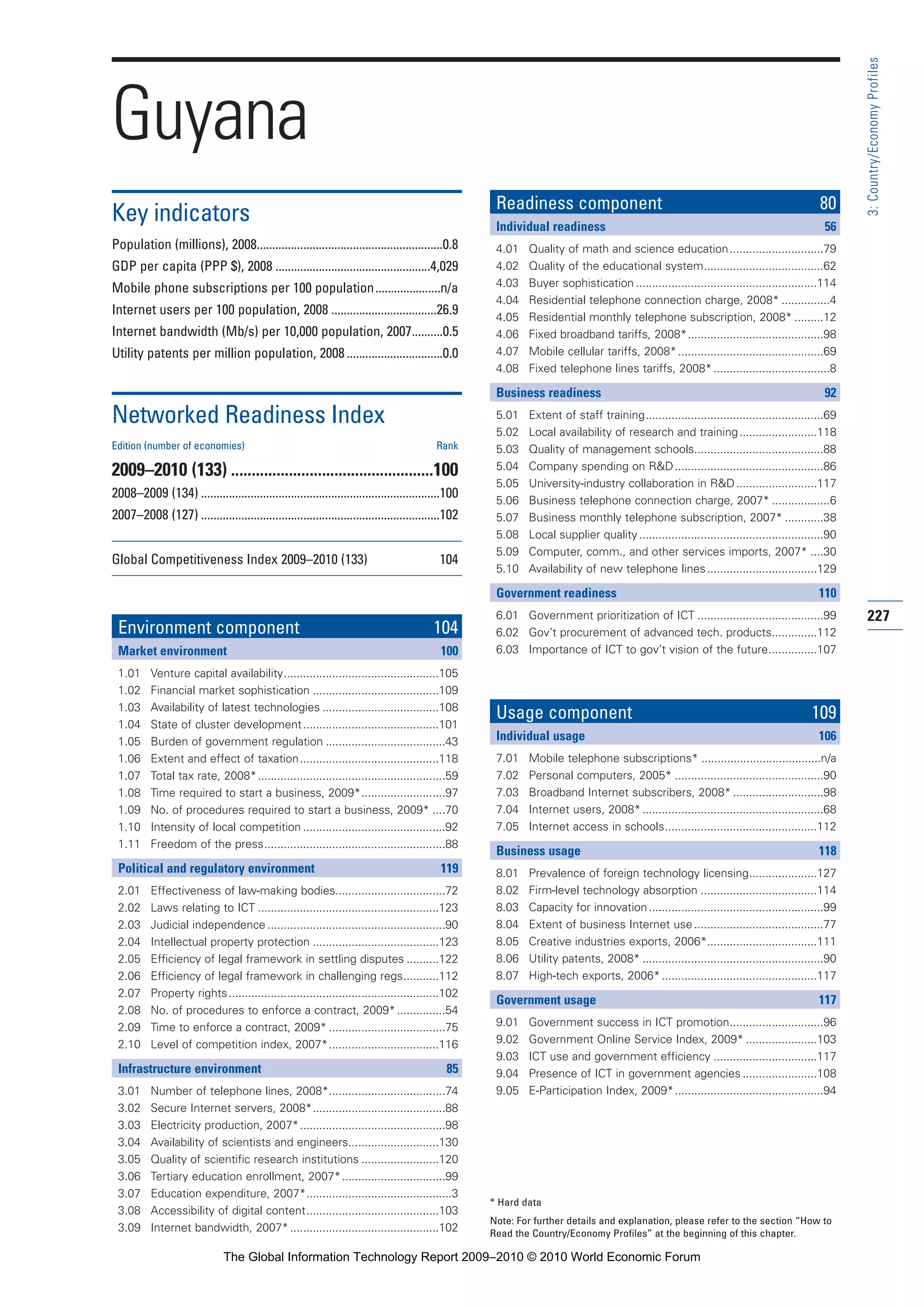

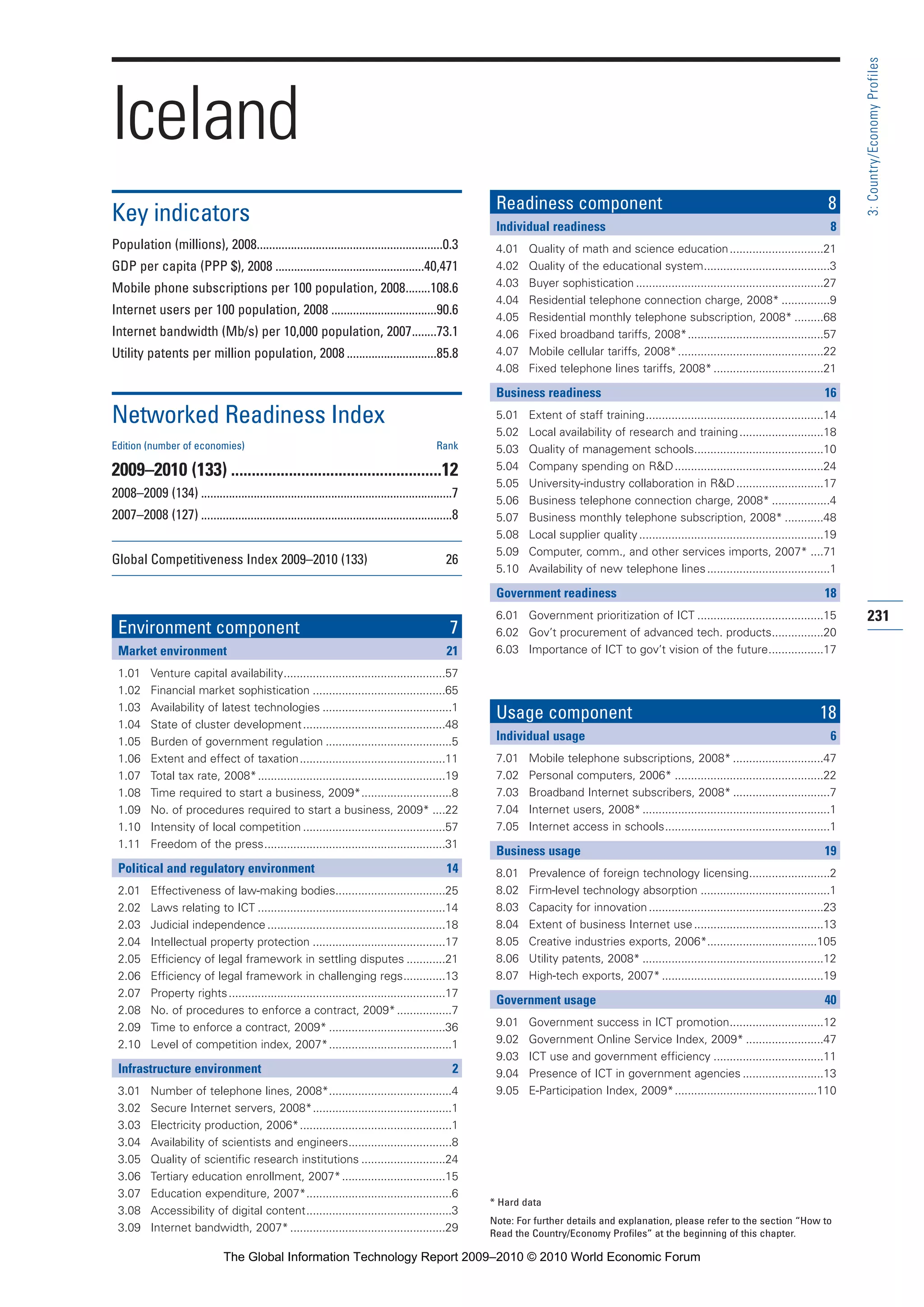

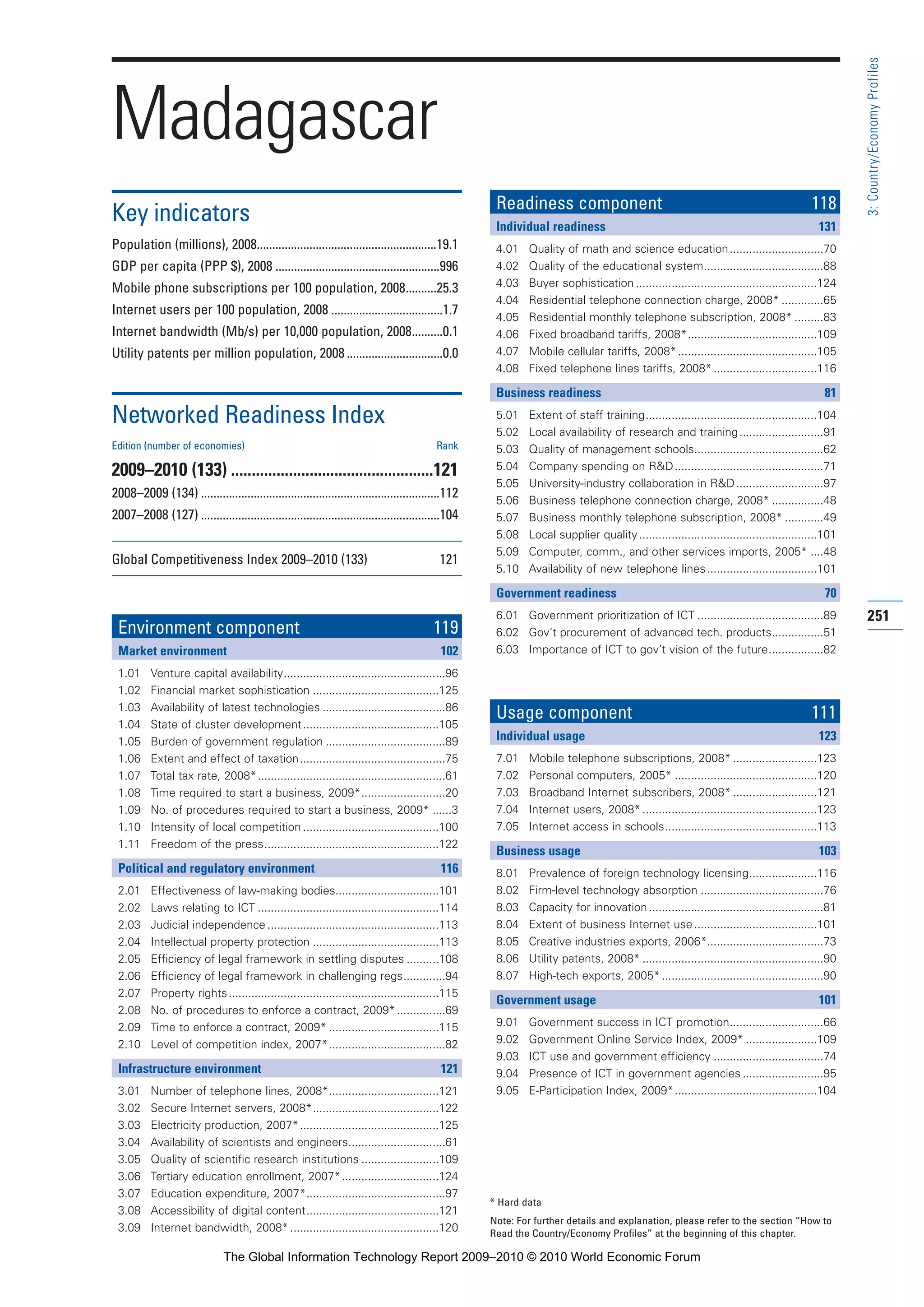

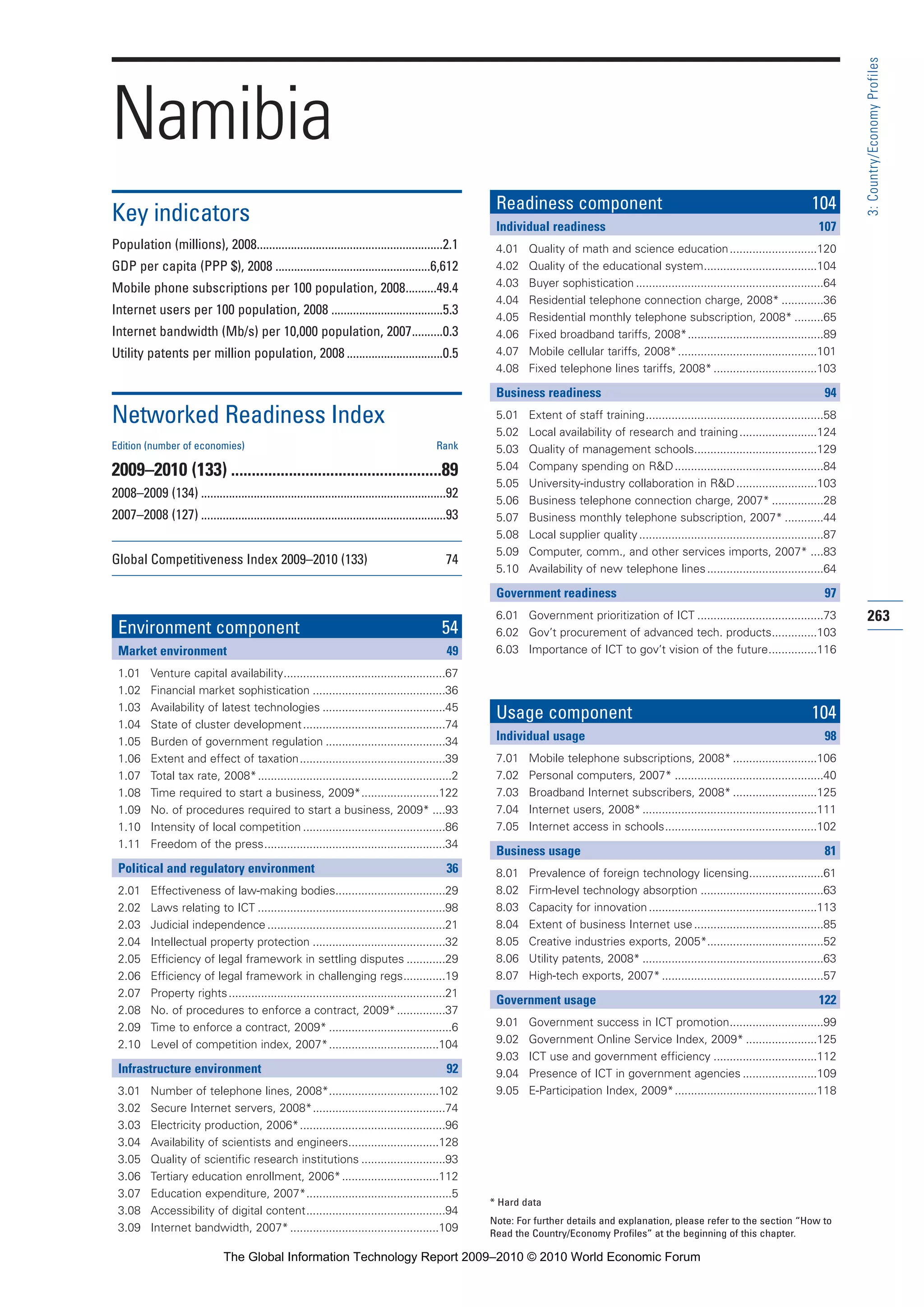

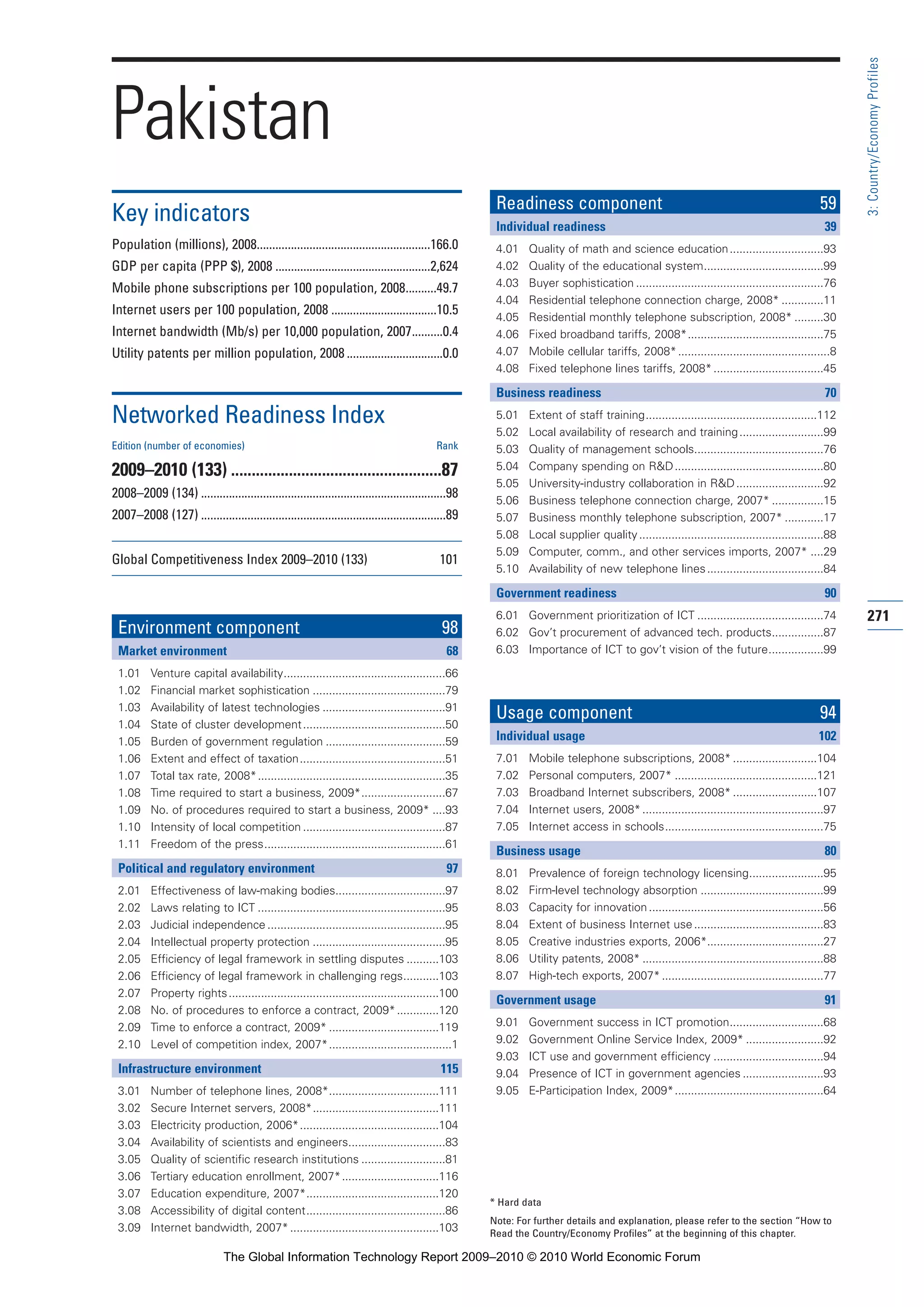

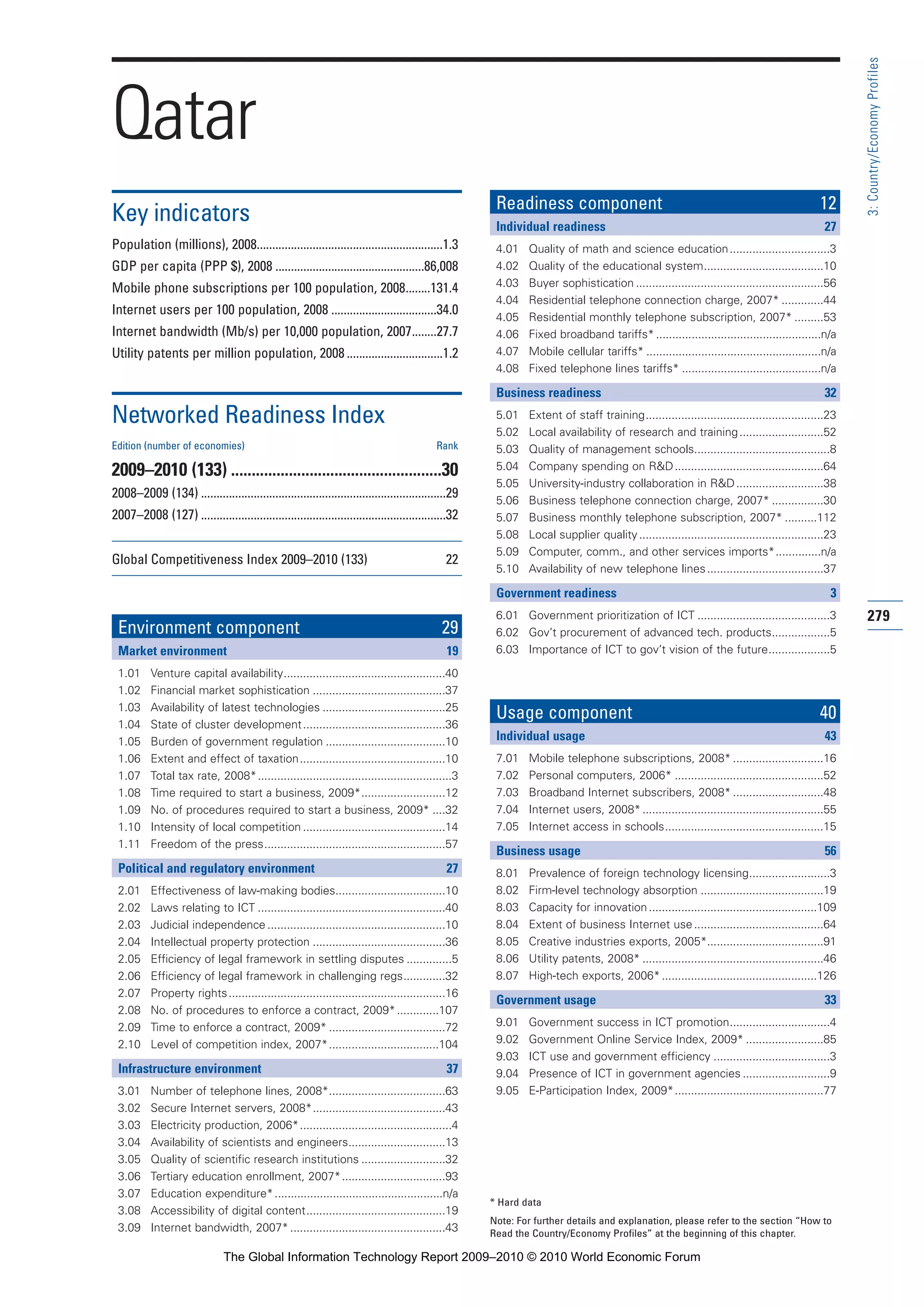

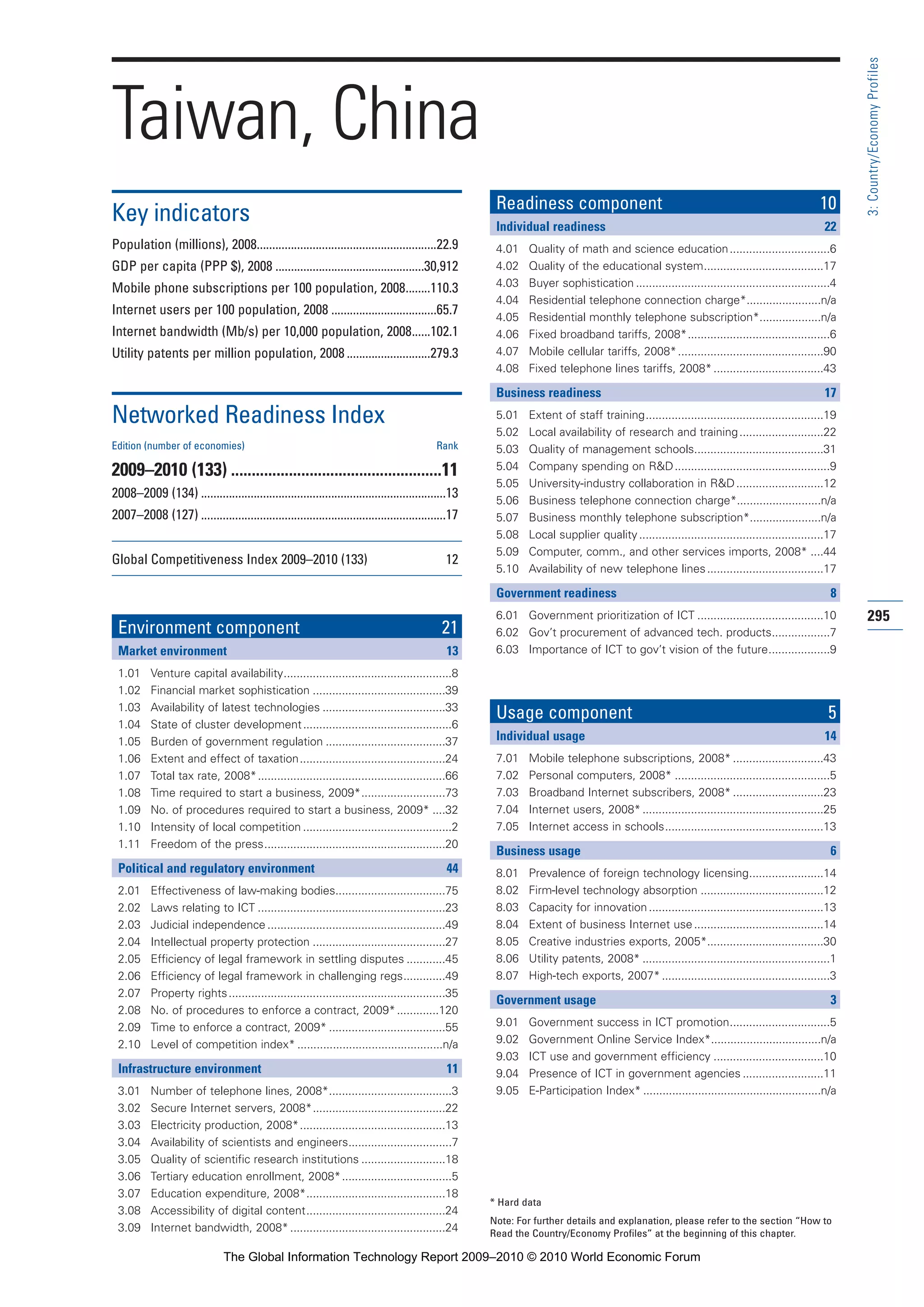

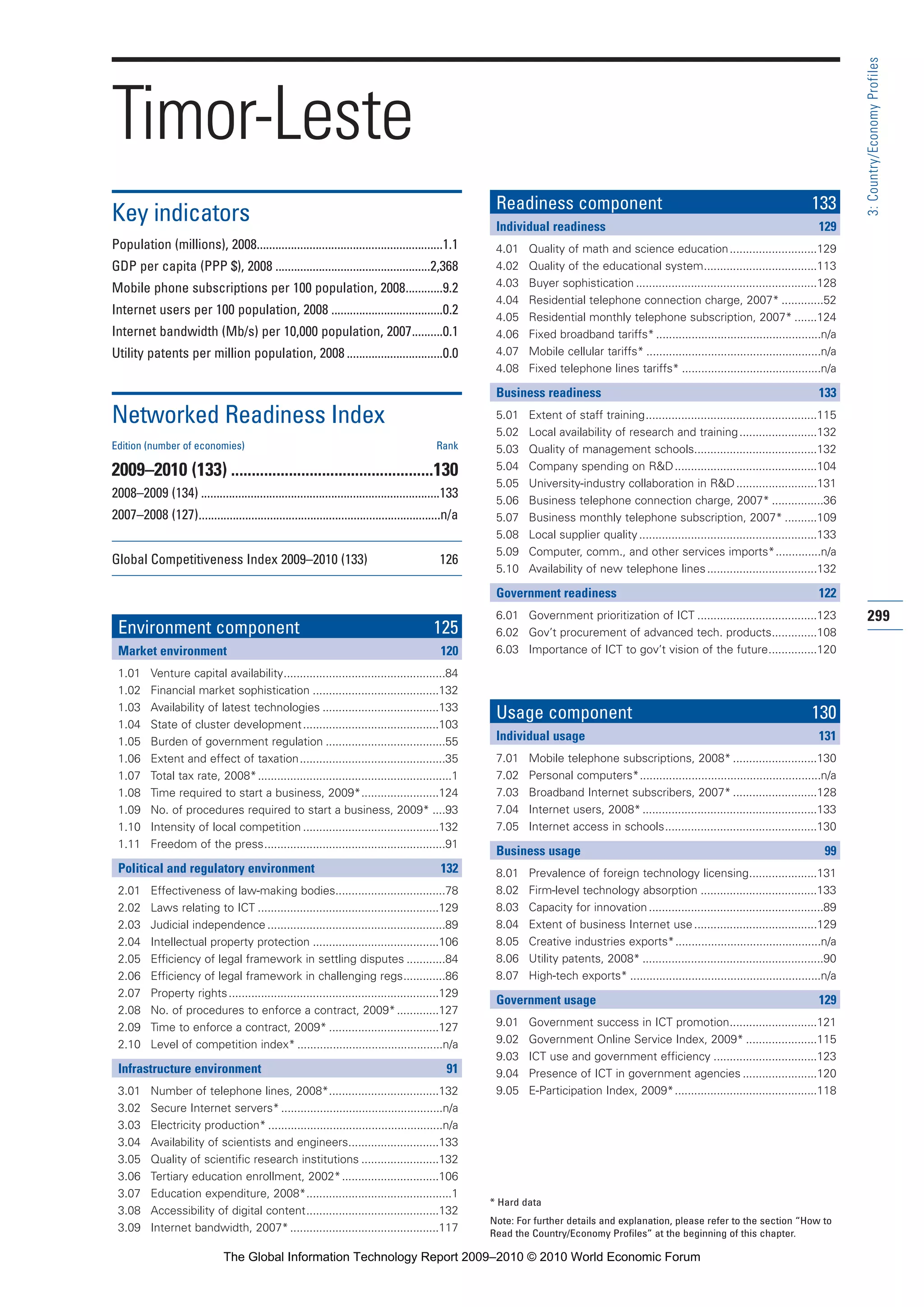

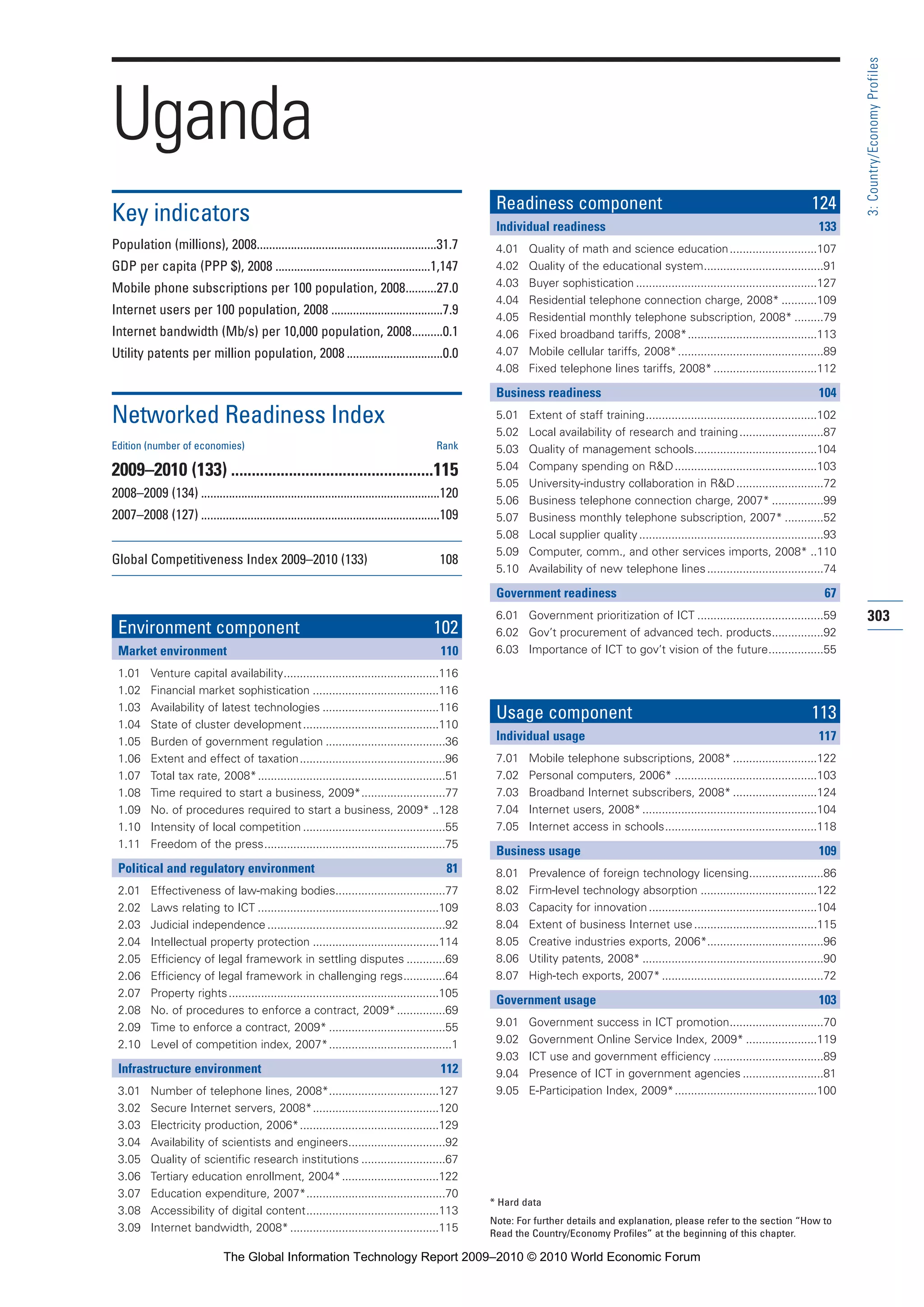

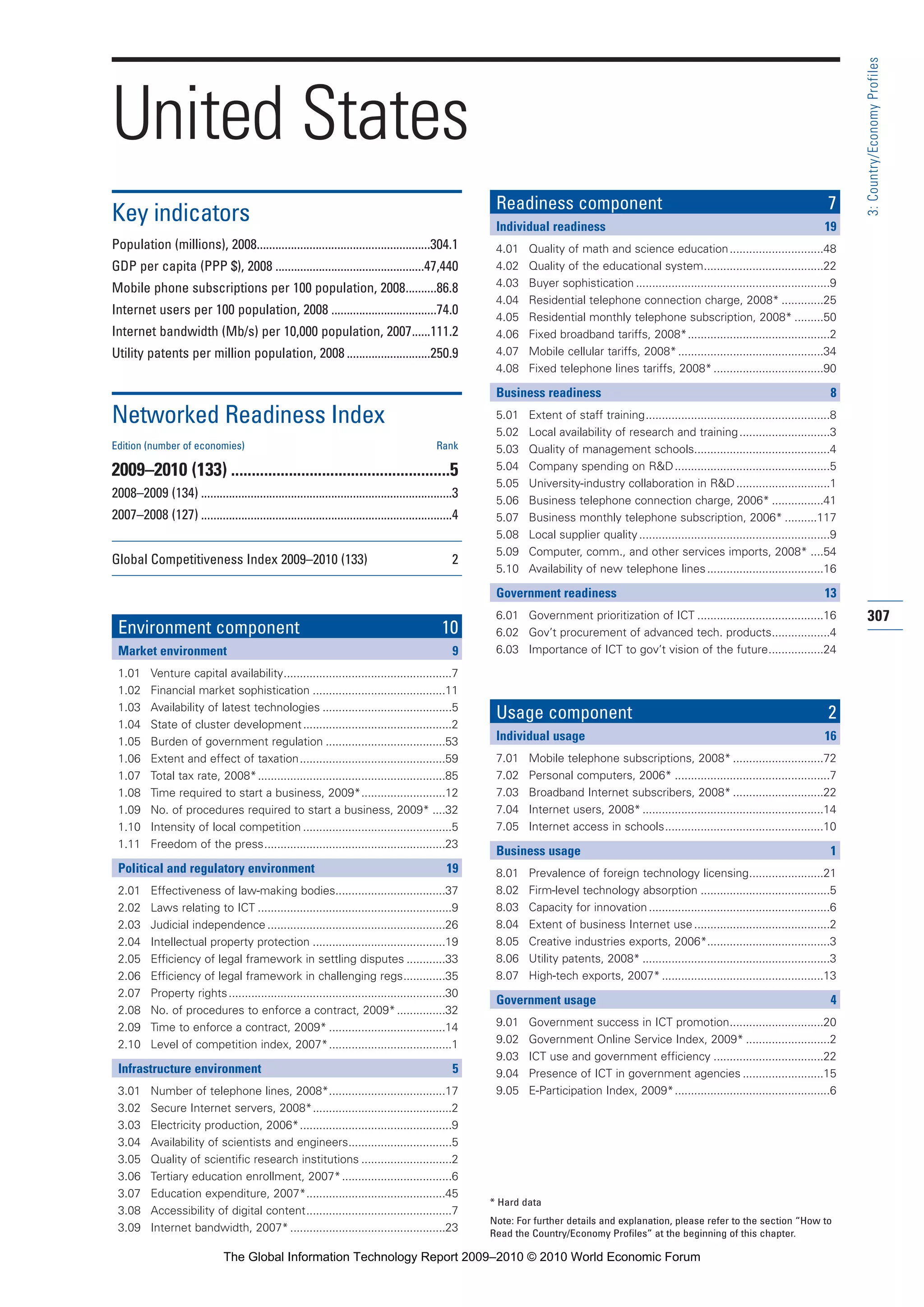

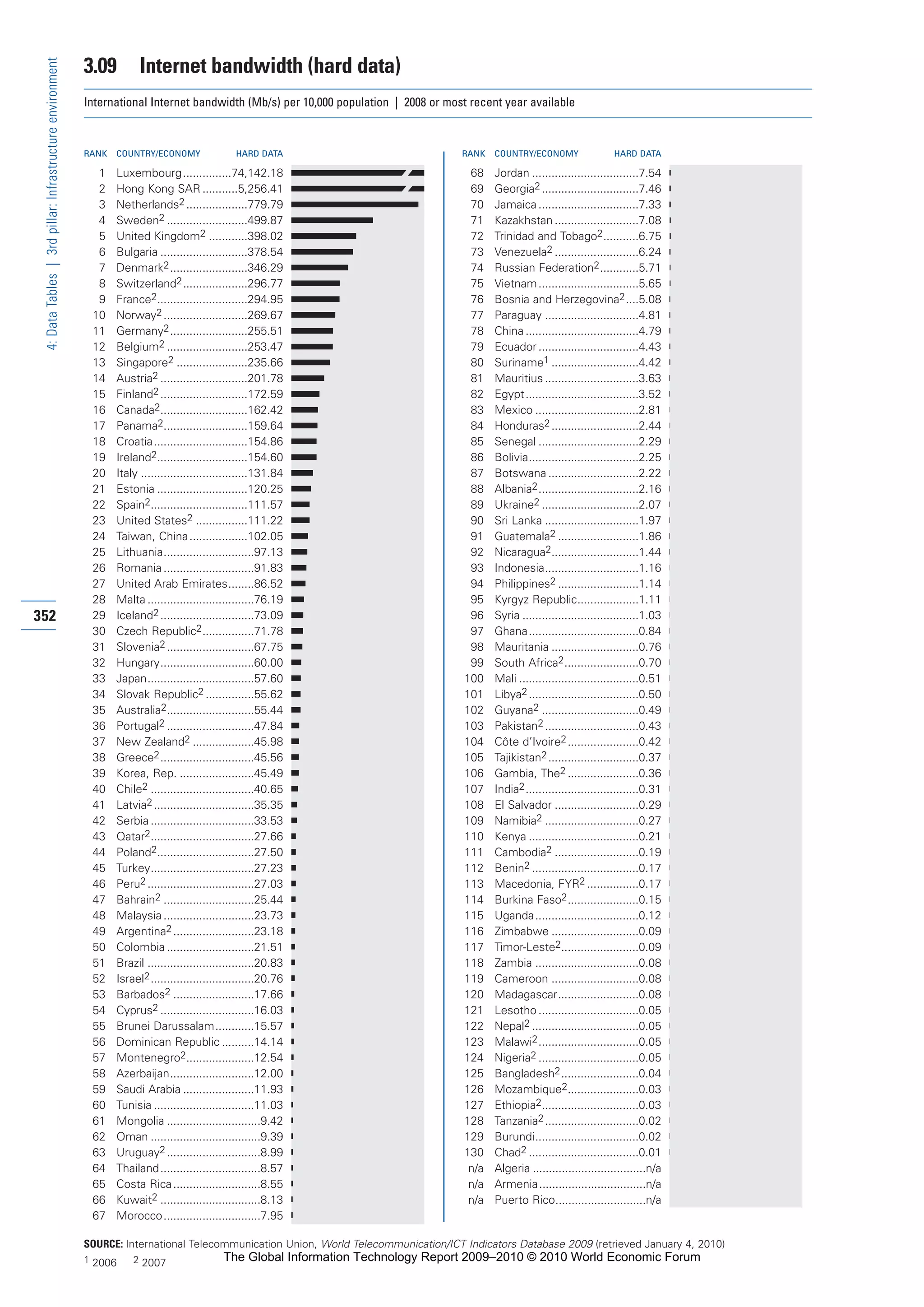

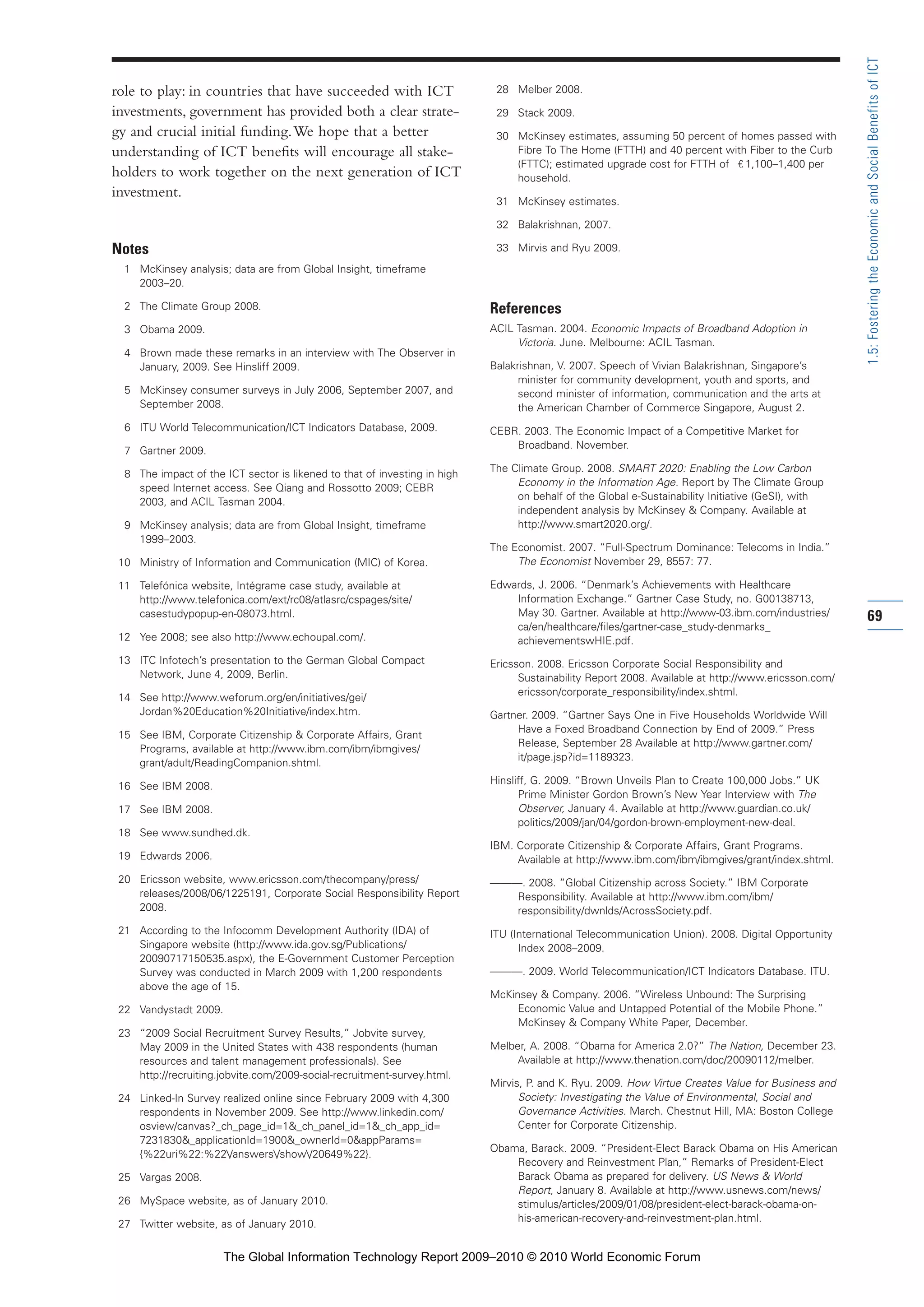

Unleashing the potential of ICT requires investments

The economic and social benefits of ICT are clear.

However, this impact could be significantly increased if

the penetration of ICT, including mobile phones, broad-

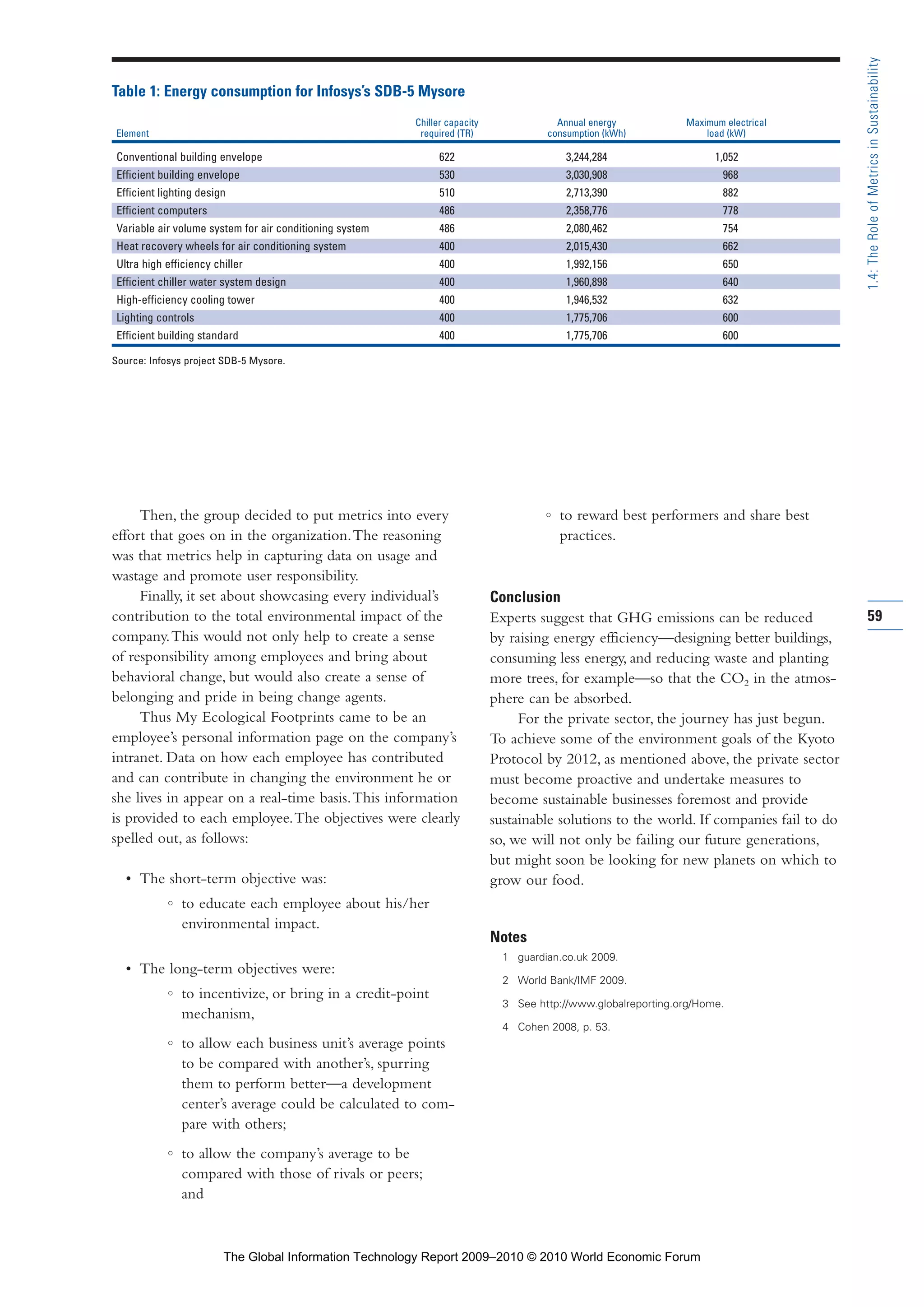

band, and PCs, was expanded. Figure 5 shows the cover-

age of these technologies in the different regions of the

world. Developed countries have room to continue to

expand their current penetration of these technologies,

but also—and possibly more pressing—emerging

economies need to close the gap with more advanced

economies to reap the benefits of ICT. If they can, ICT

will likely bring them even more significant benefits

than it will to developed economies.

Increasing the penetration levels of high-speed

broadband, mobile, and PCs wasin developed and devel-

oping countries will be extremely costly and is not like-

ly to be profitable for ICT companies alone. For exam-

ple, in the EU15 countries, McKinsey estimates that the

capital investments required to bring high-speed, fixed

broadband networks will be as much as 250–300 bil-

lion over the next couple of years.30

But in this same

region, the industry will generate some 250 billion in

cash flows over the next five years.31

That means that

the industry would need to invest all available cash to

build these networks, leaving nothing for maintenance

or other types of network upgrades, or anything else.At

its current investment rates, the industry would take

some 15 years to roll out new networks.The situation is

obviously even more unbalanced in emerging economies,

where penetration levels are lower—and consequently

the necessary investments would be higher—than in

Europe.

The estimates above indicate that governments,

at least in Europe, will need to invest large amounts

of money to enable their countries with ICT. Making

these investments work will require a concerted

approach among all industry stakeholders.

All stakeholders need to adapt their strategies and

cooperate

It is no easy task to align the interests of the various

stakeholders when so much is at stake: ICT companies

seek revenue, governments seek access to innovative

services and tax revenues as well as economic growth,

66

1.5:FosteringtheEconomicandSocialBenefitsofICT

Part 1.r2 3/2/10 4:40 AM Page 66

The Global Information Technology Report 2009–2010 © 2010 World Economic Forum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cusersdesktop2010gitr2009-2010fullreportfinal-100402152331-phpapp01/75/The-Global-Information-Technology-Report-2009-2010-86-2048.jpg)

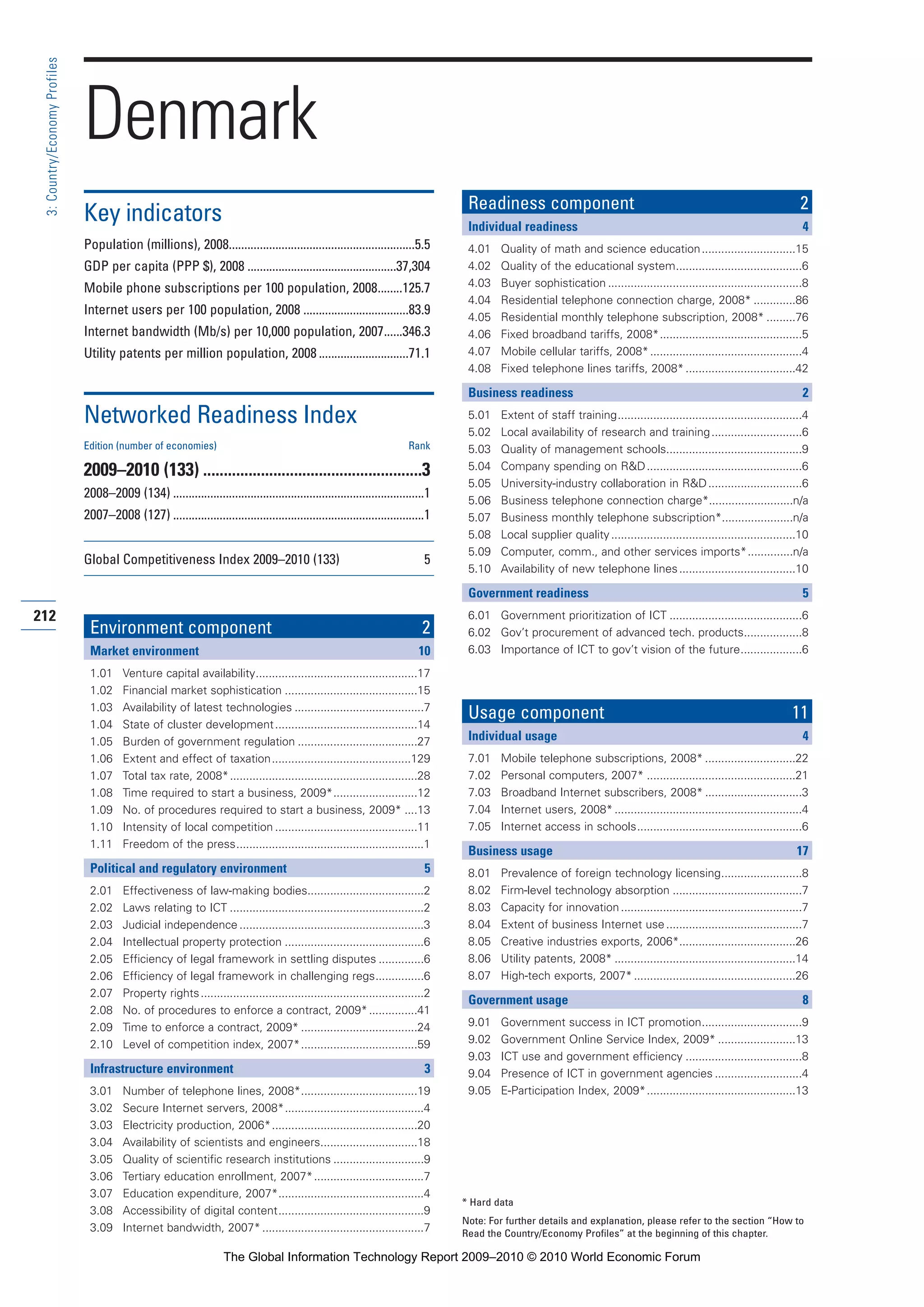

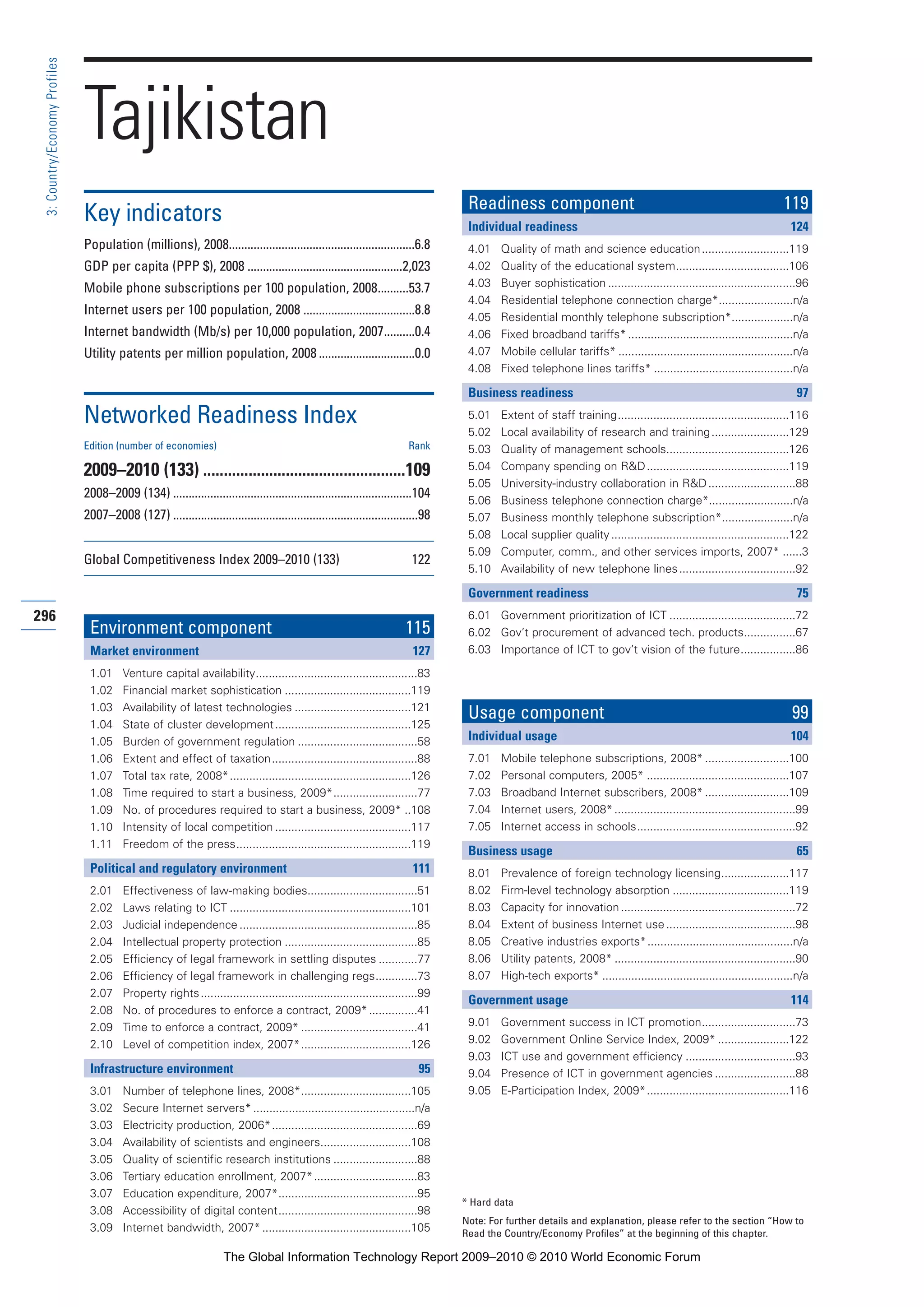

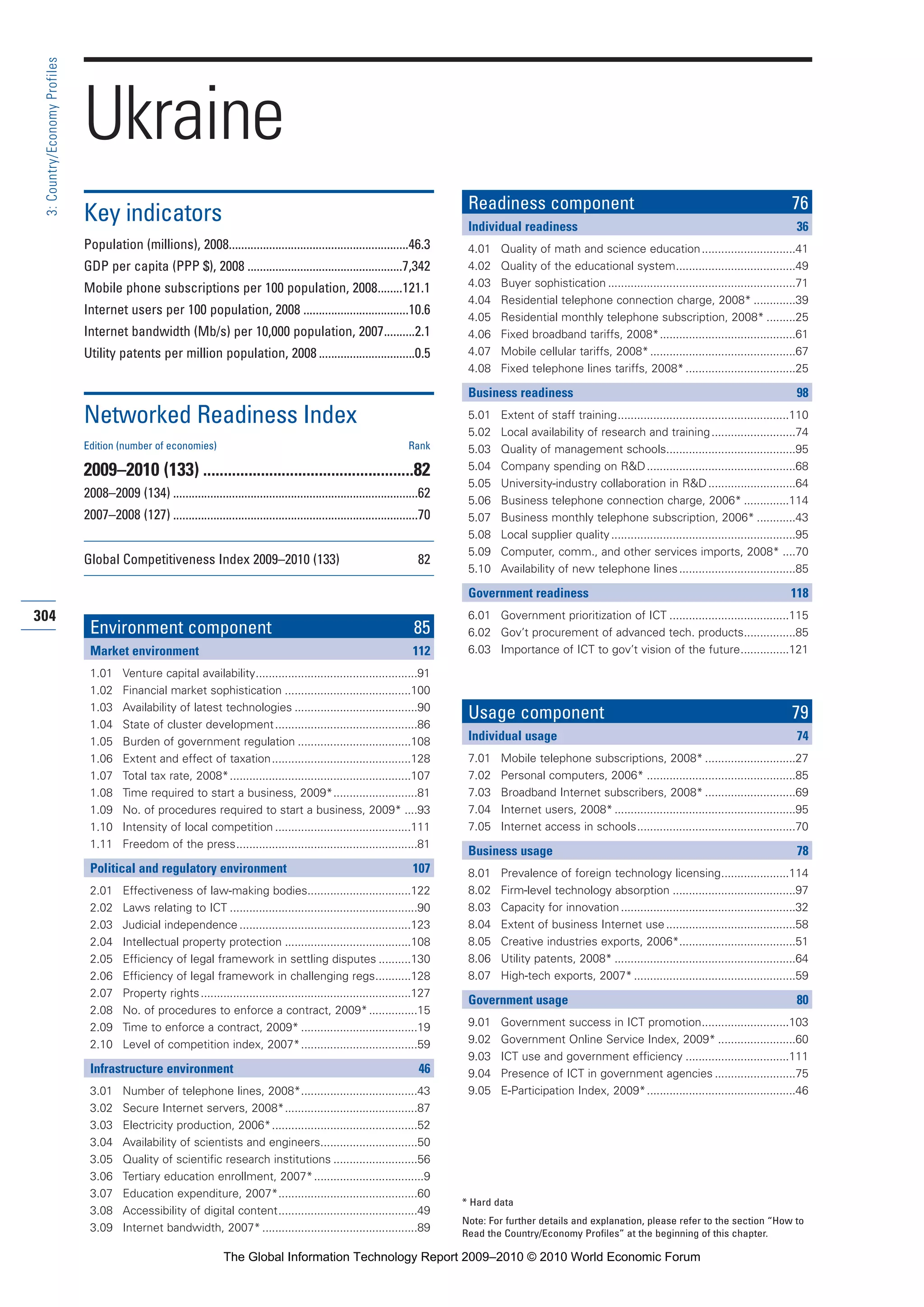

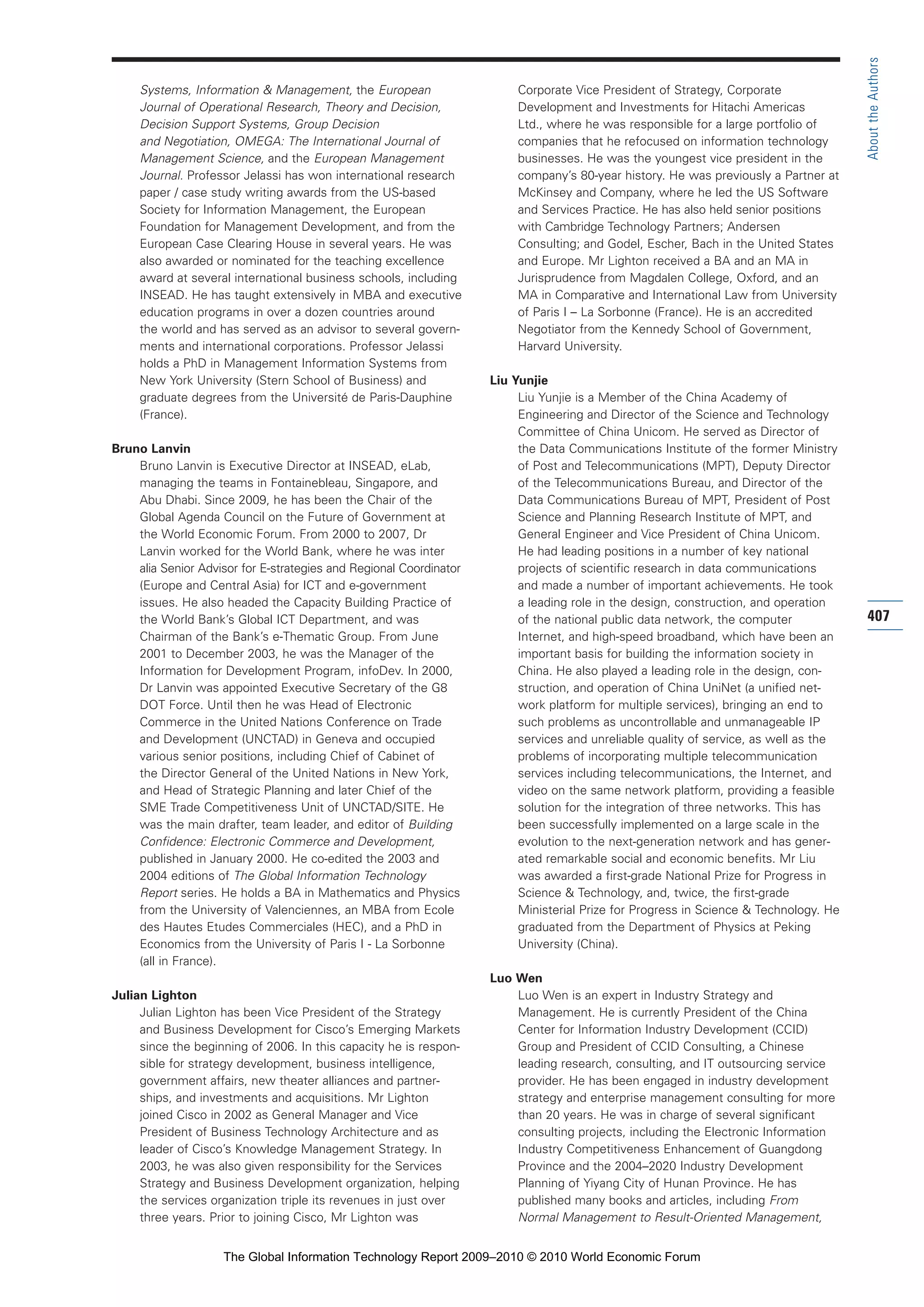

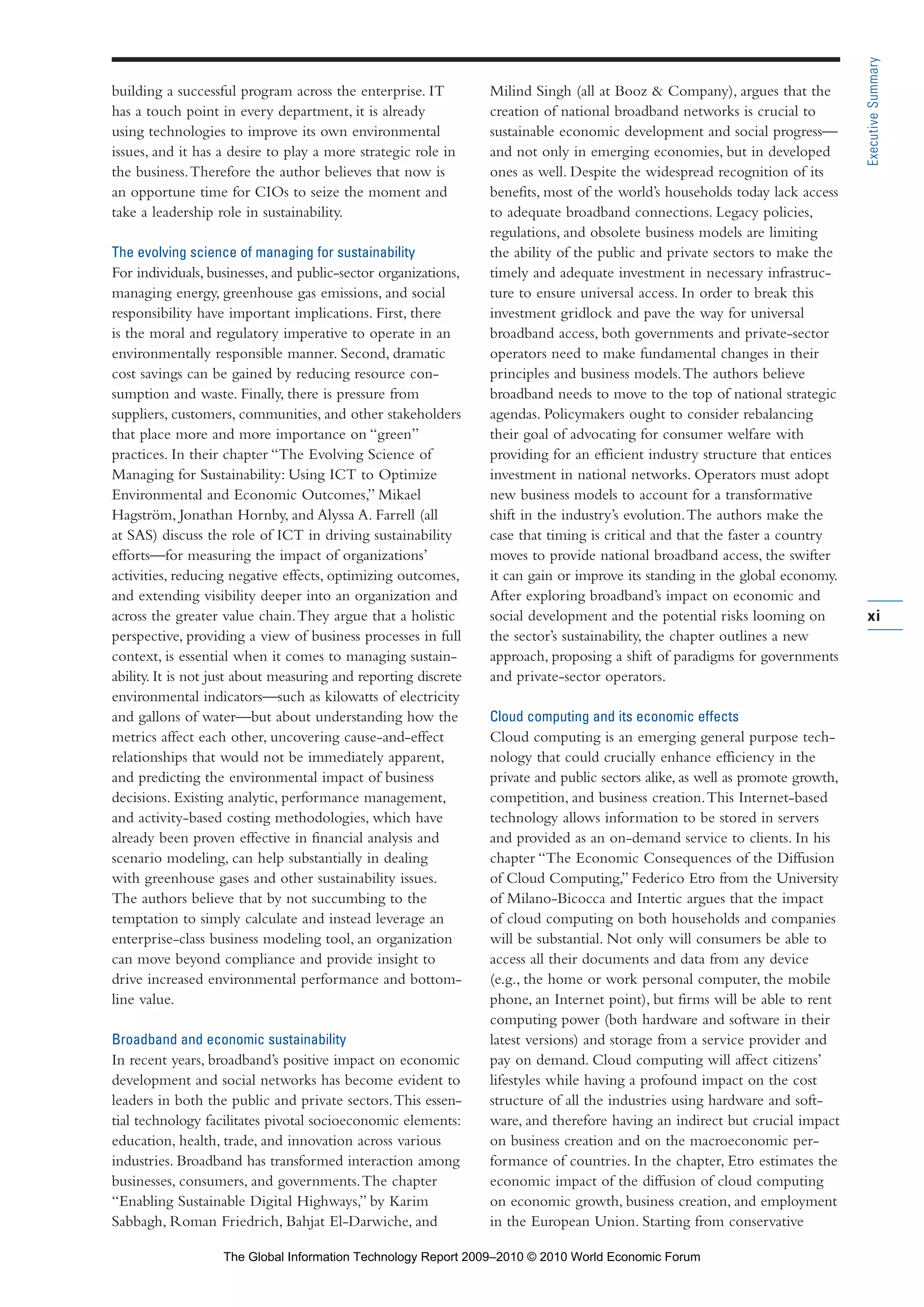

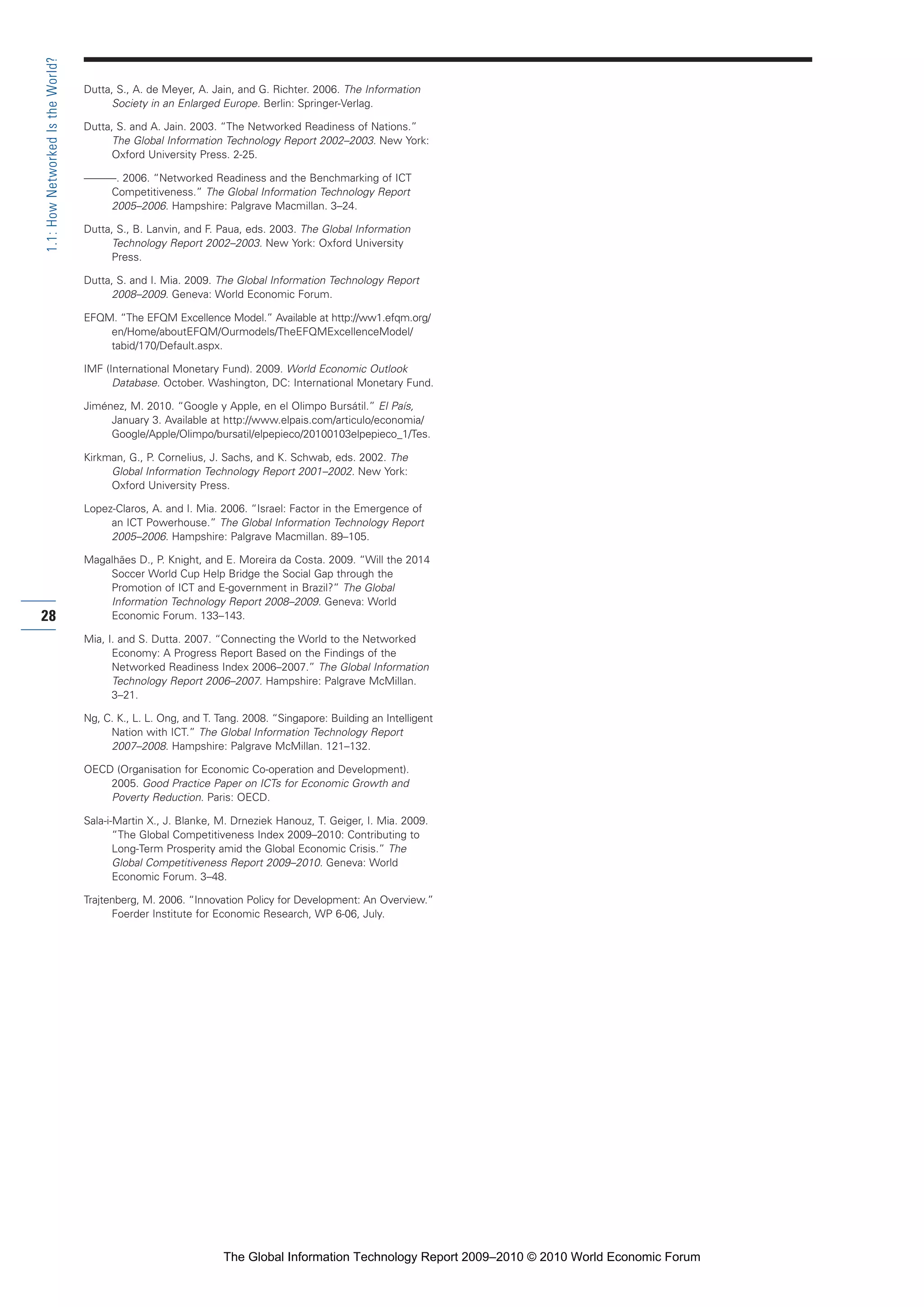

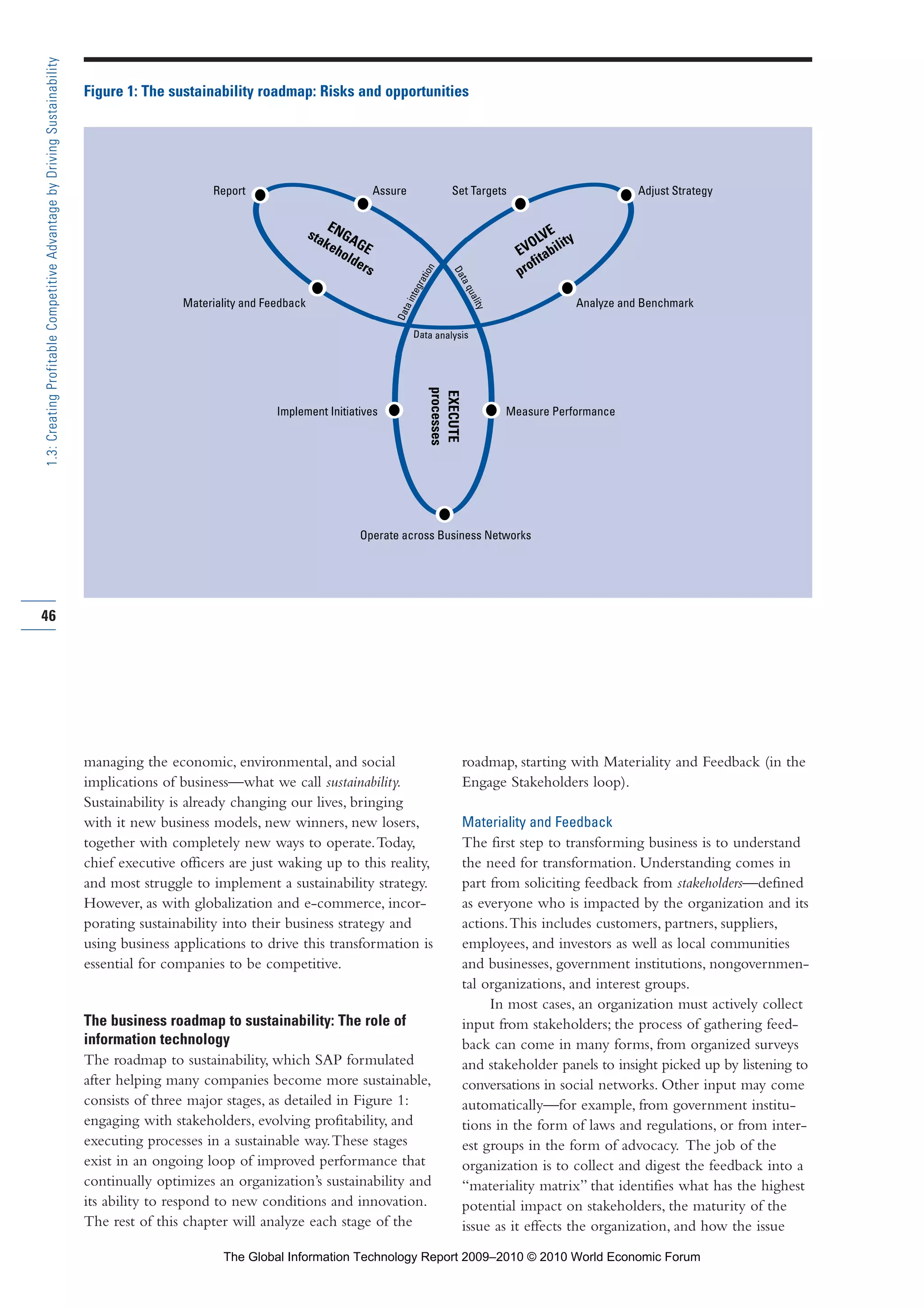

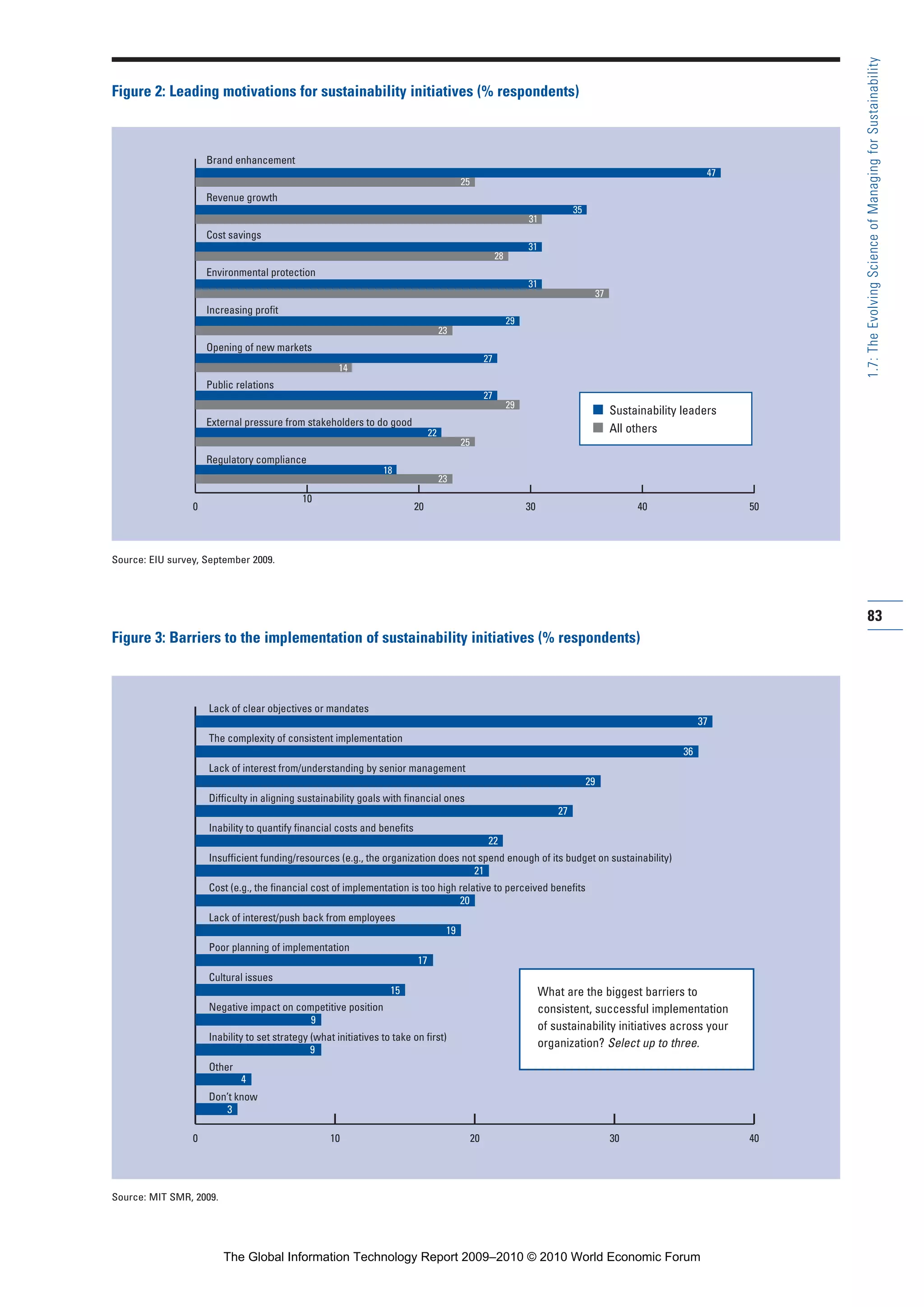

![Sources of CO2

equivalents

Resource module

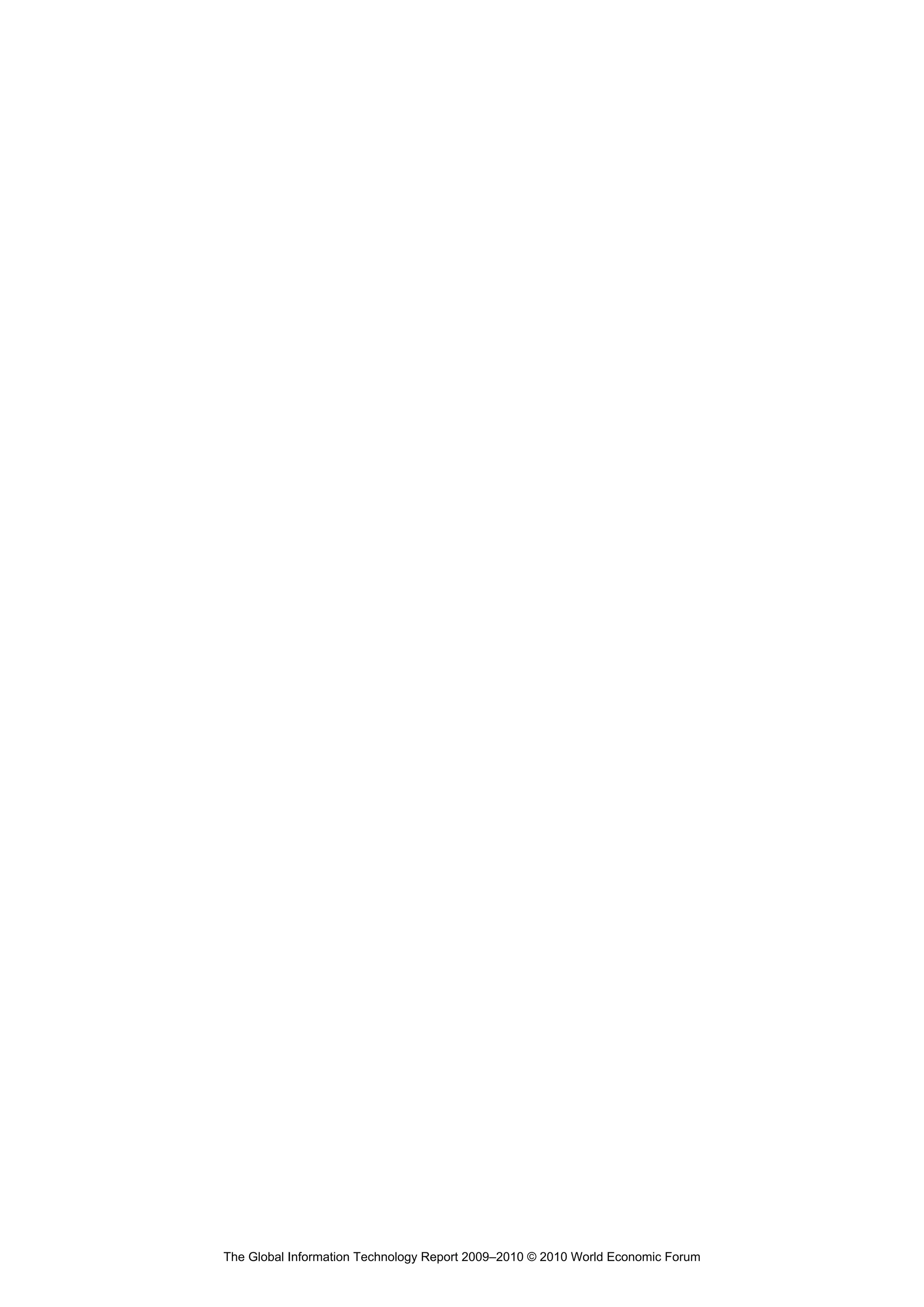

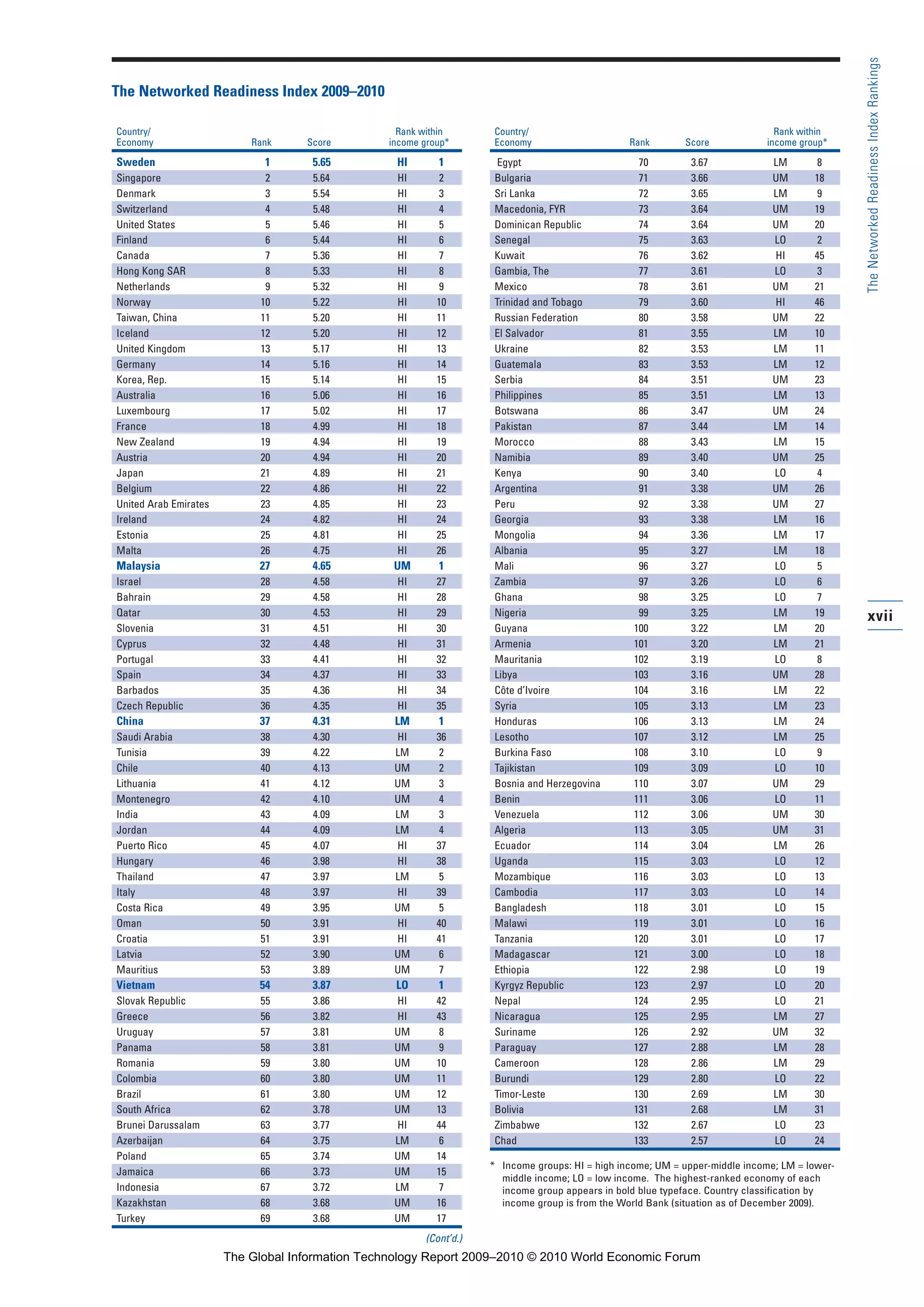

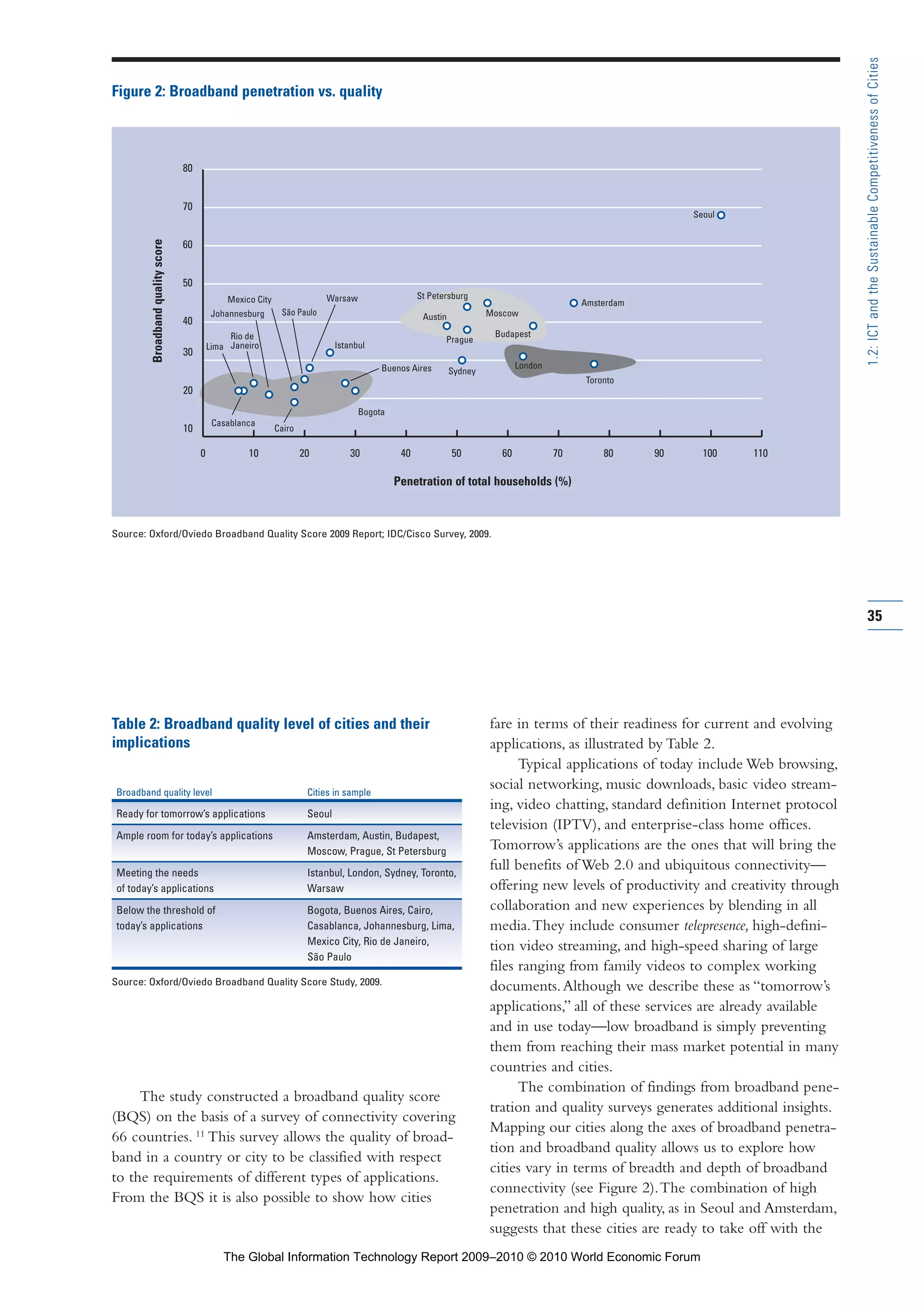

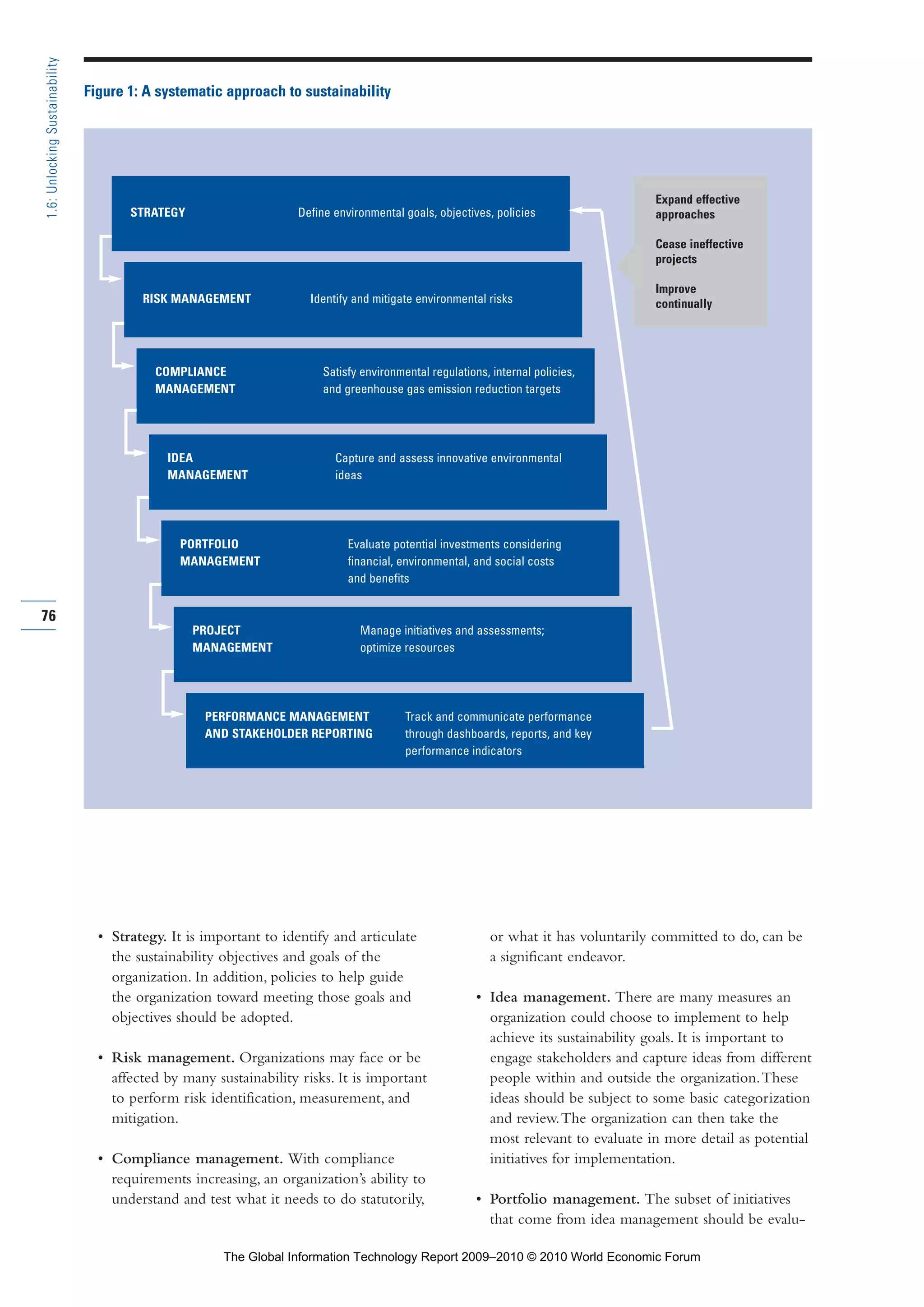

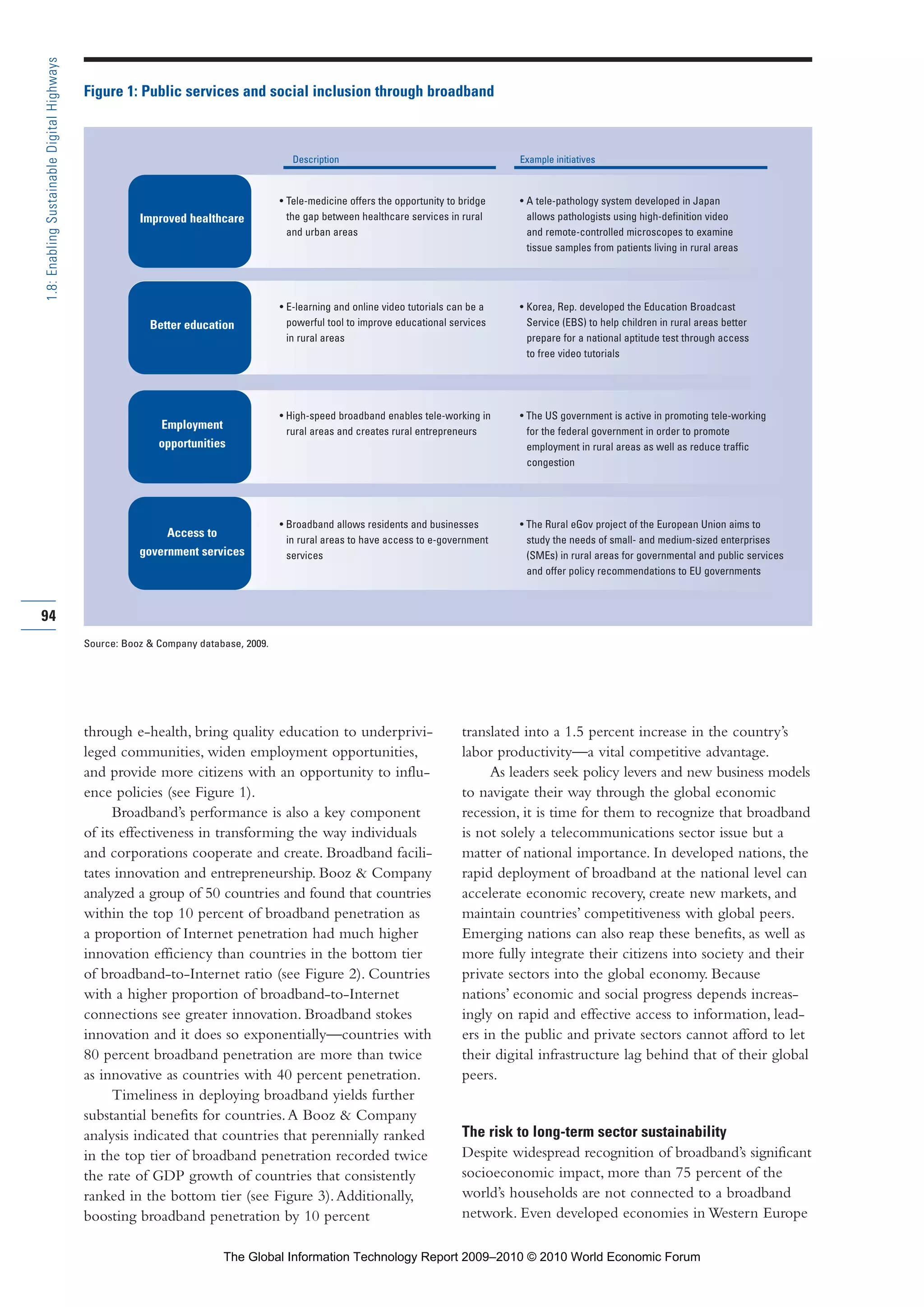

As a simple example, to reduce the energy use of a

building one must change the properties of the building

itself or manage what goes on inside that building.To

do this, one must understand how these activities affect

the use of the building—activities that are not usually

measured or metered independently.

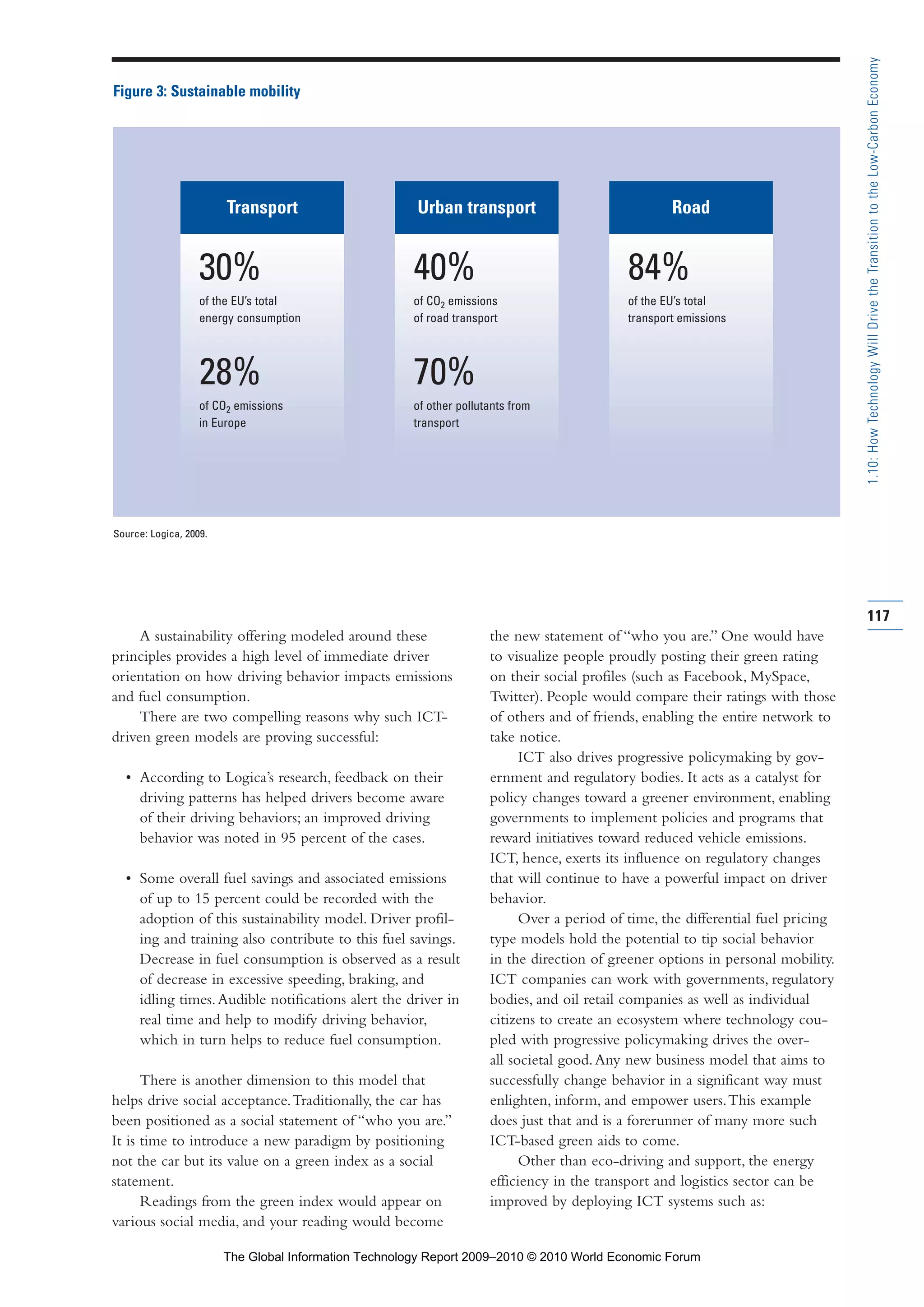

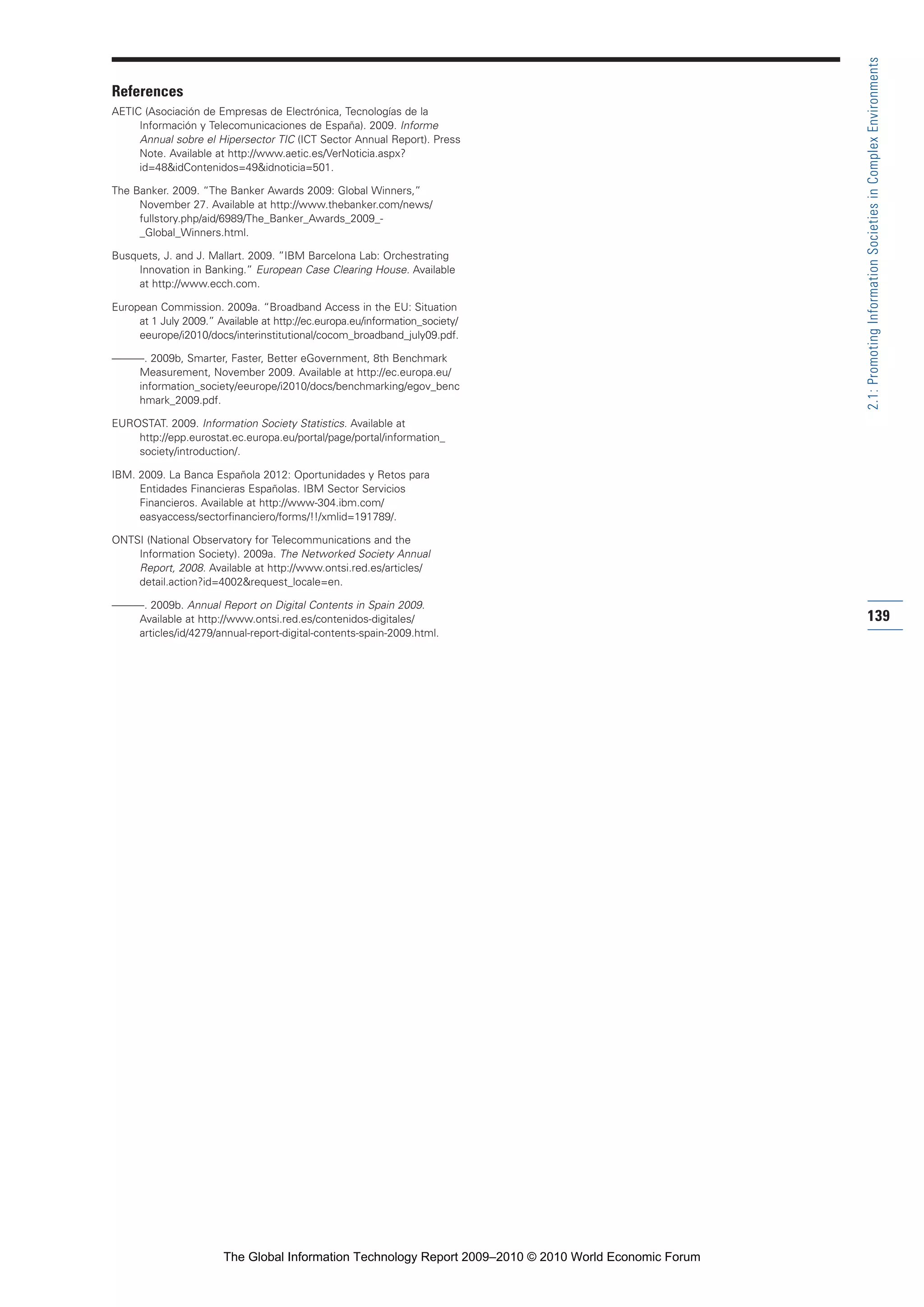

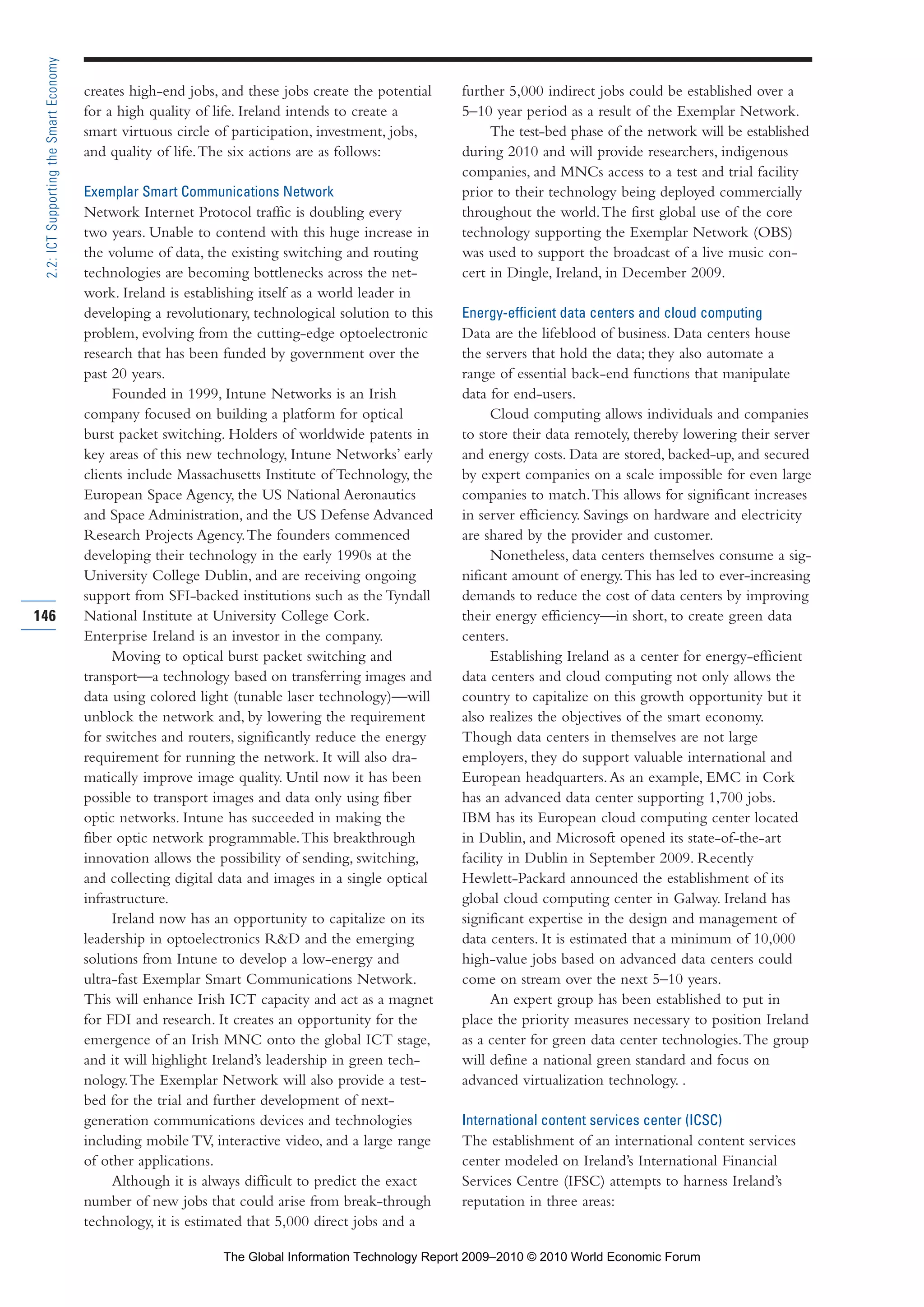

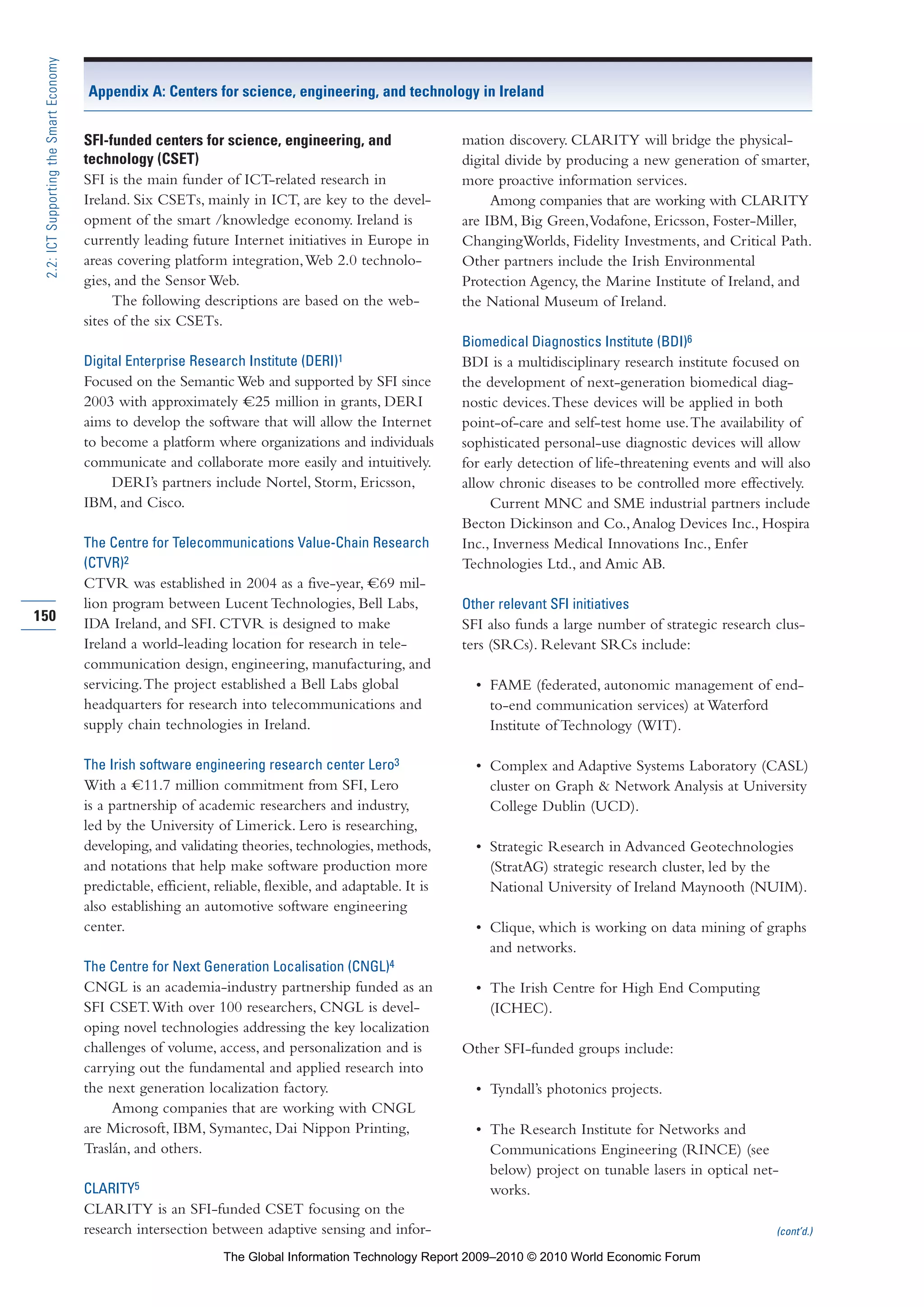

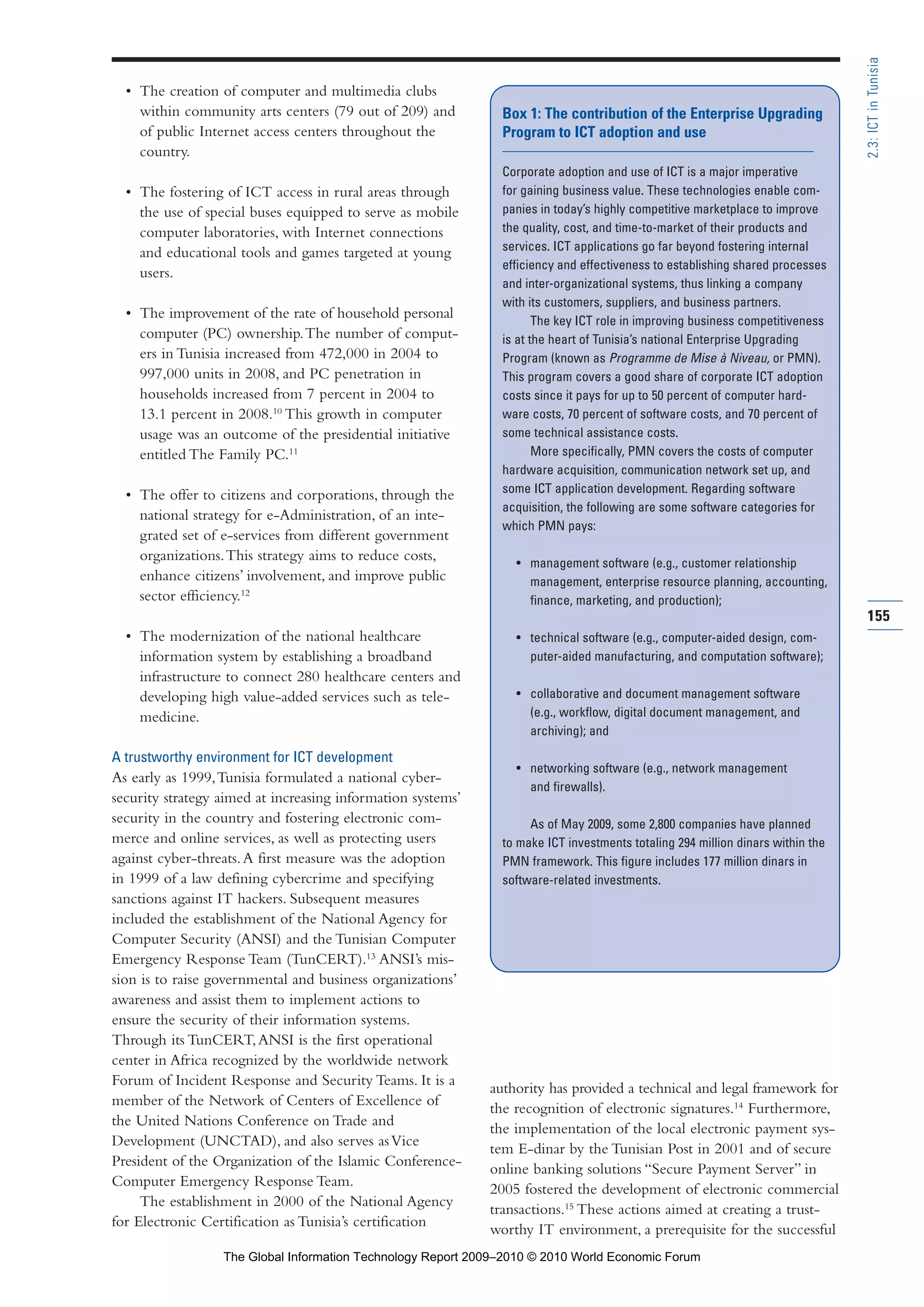

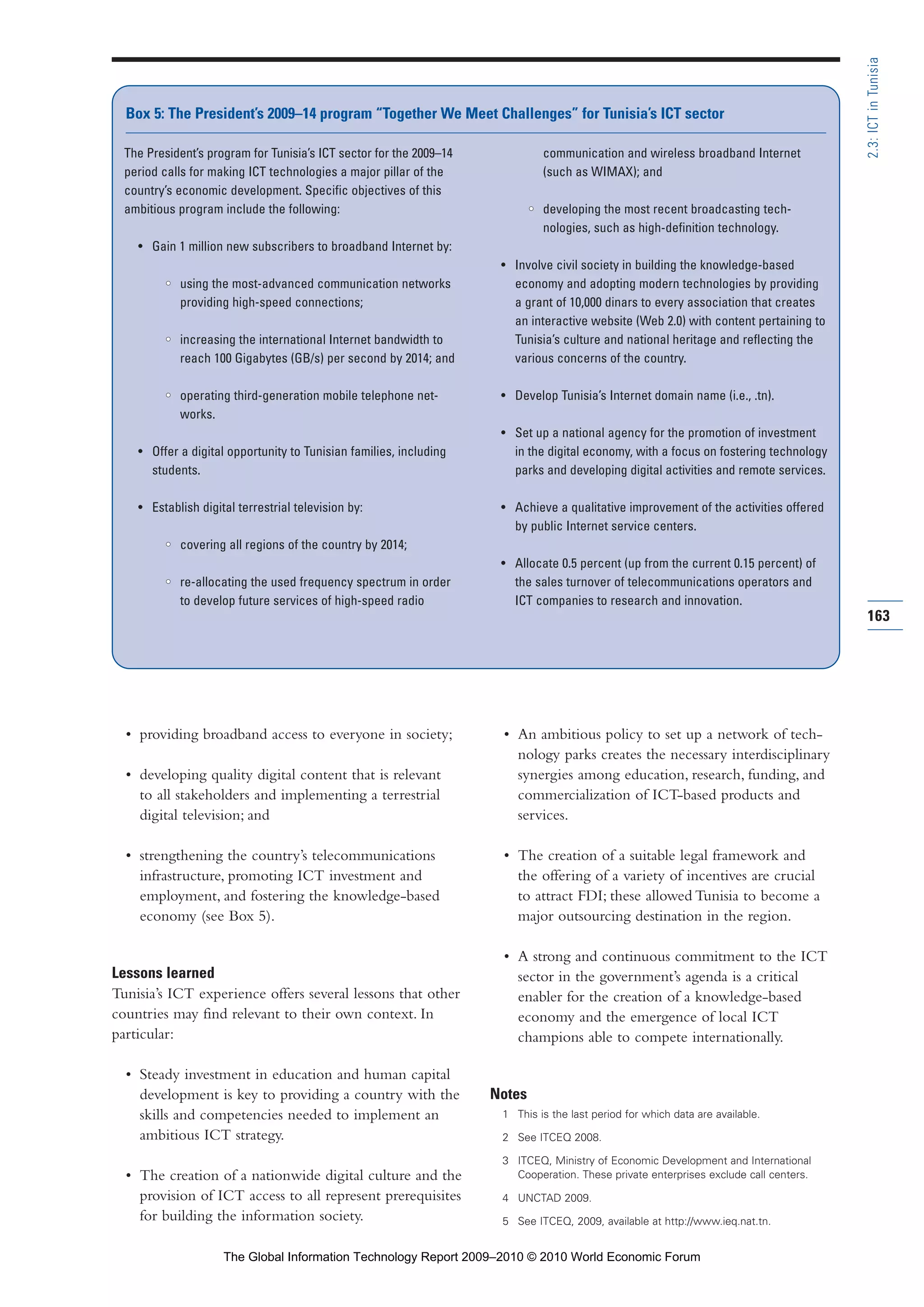

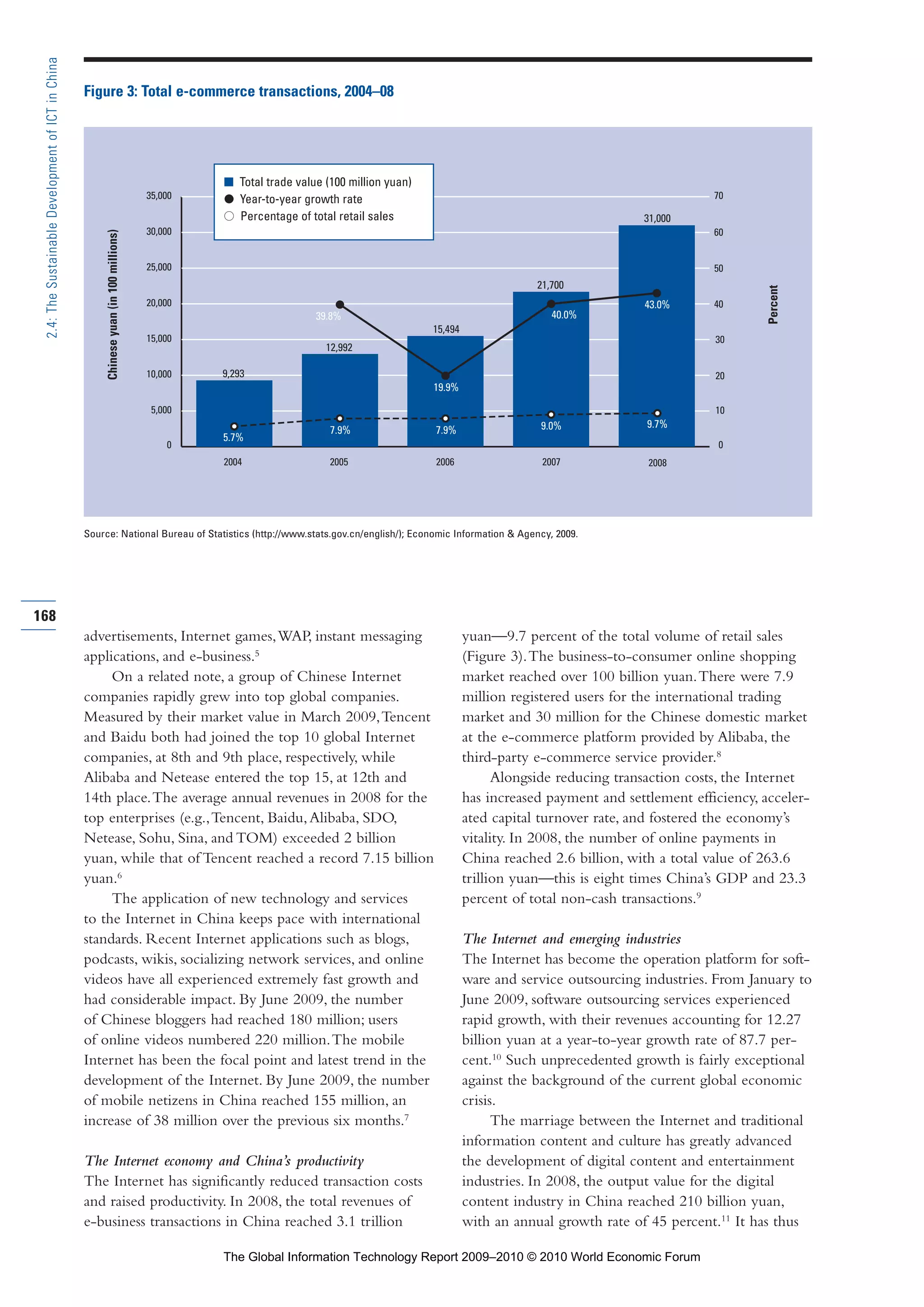

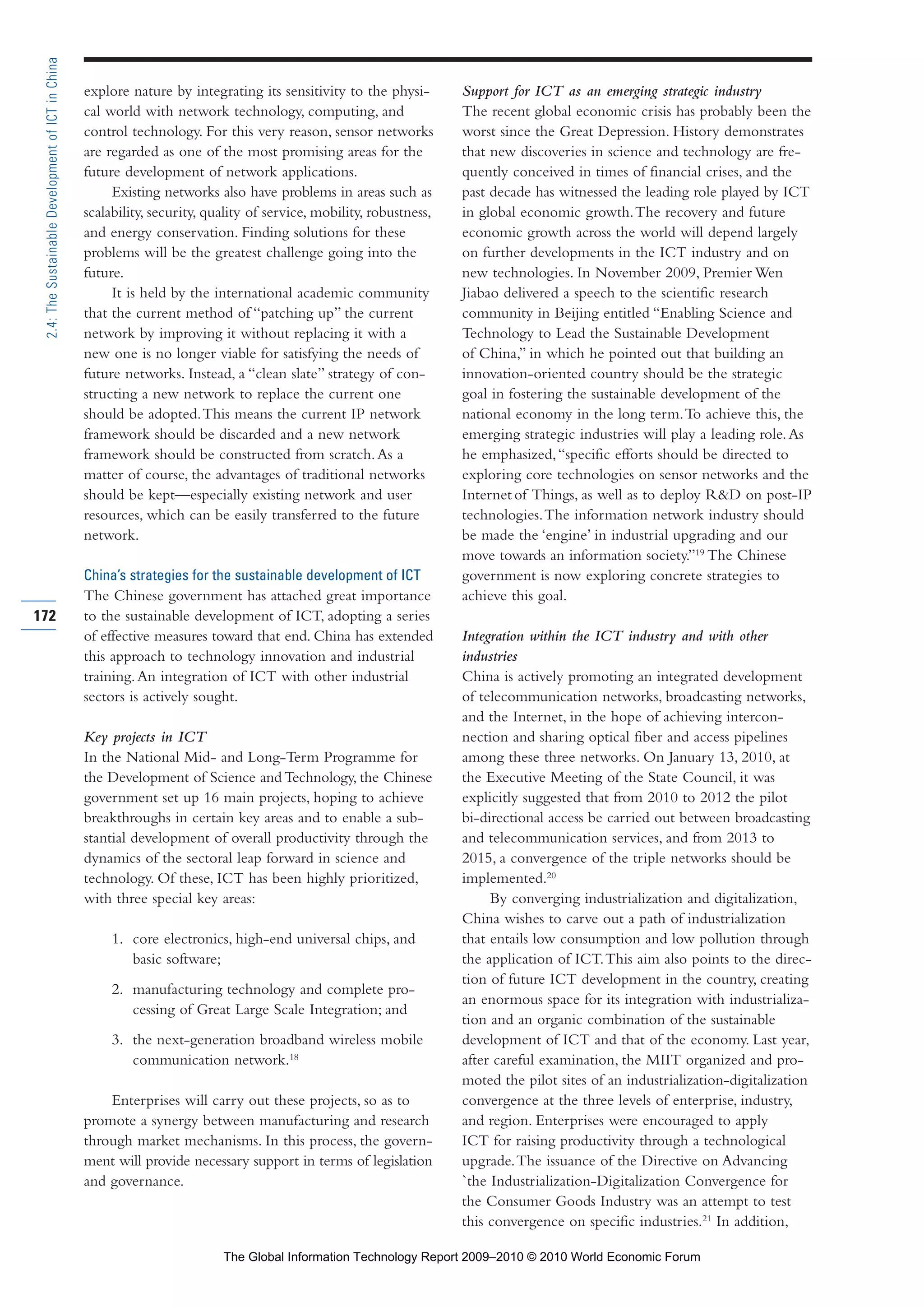

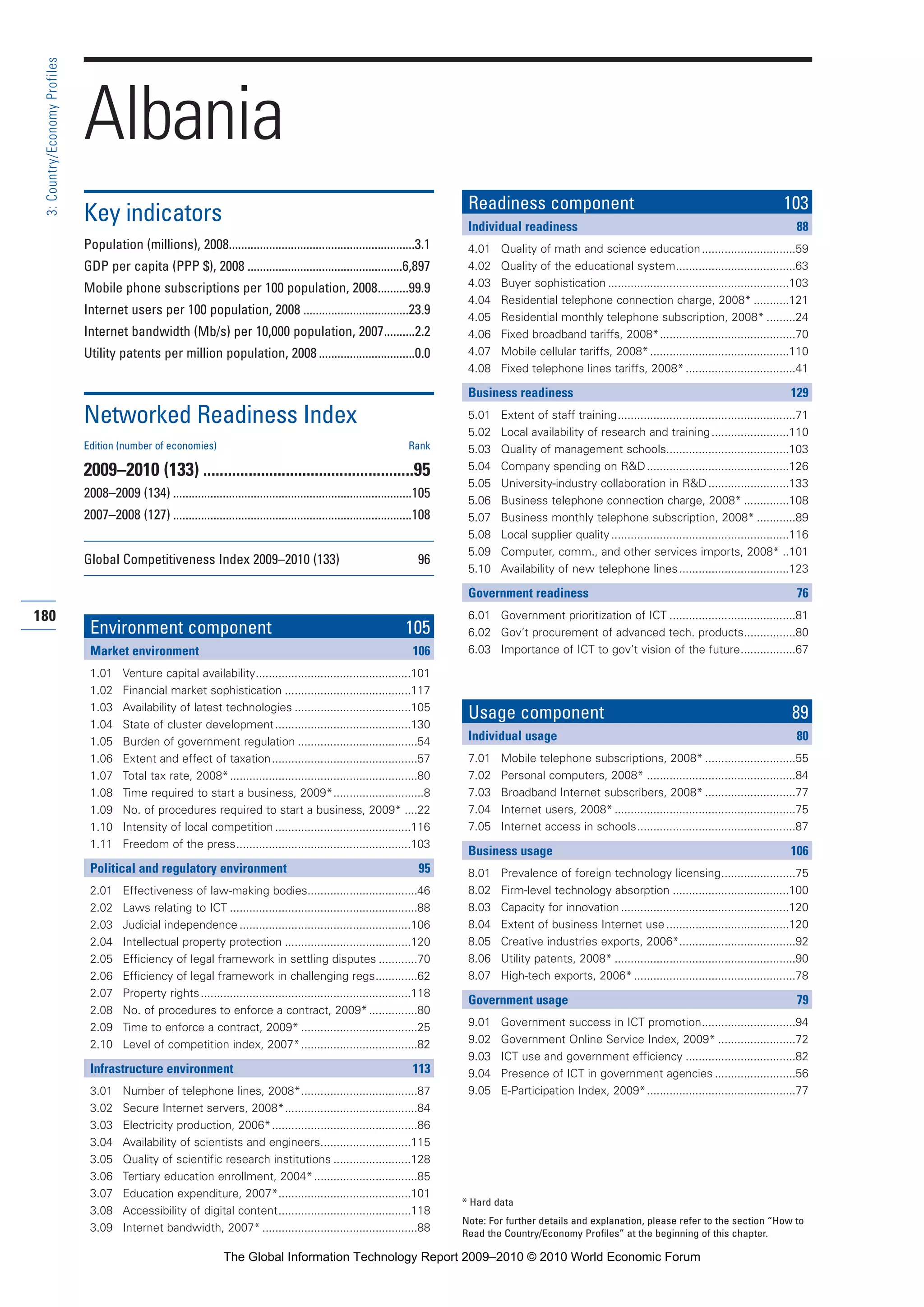

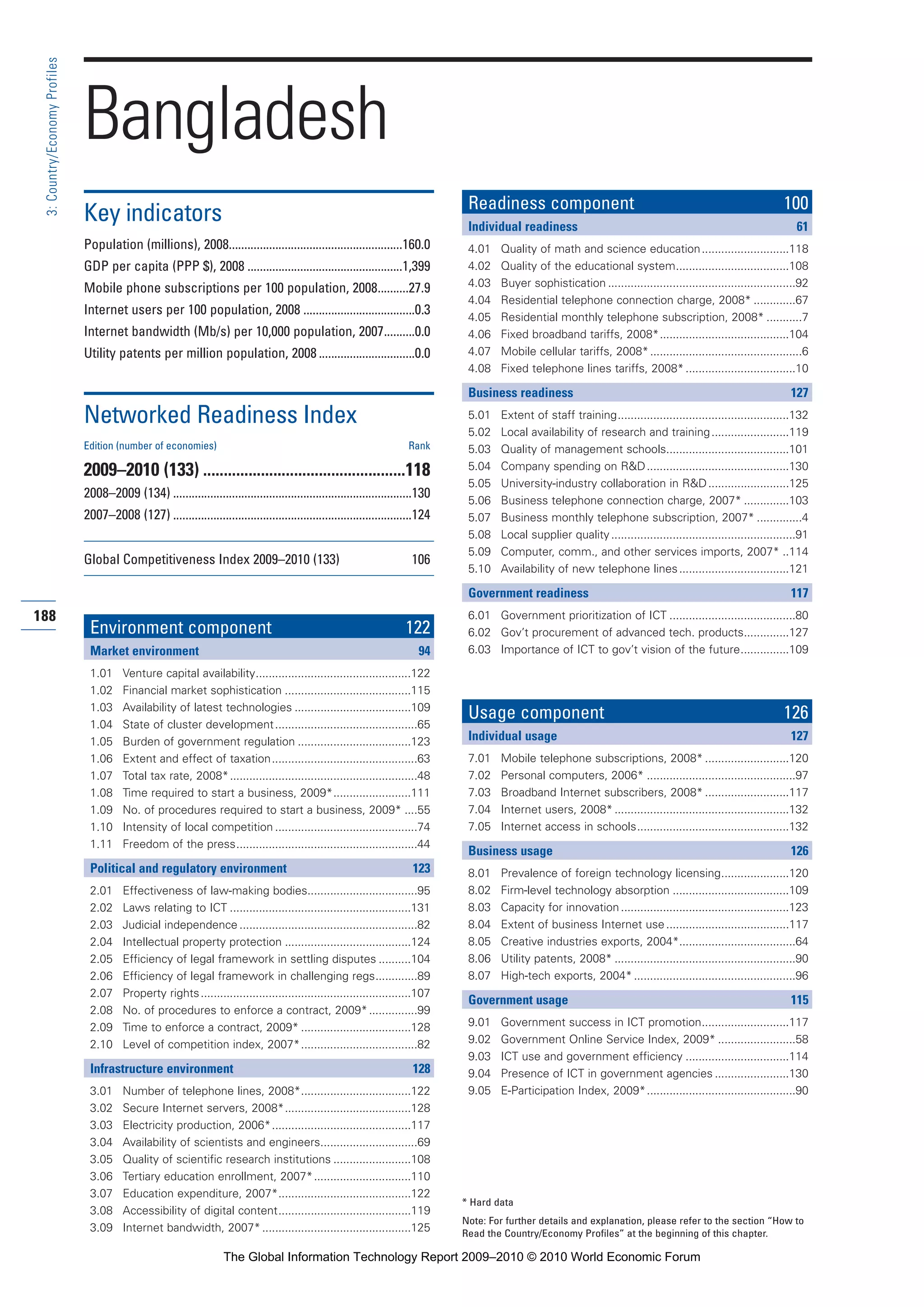

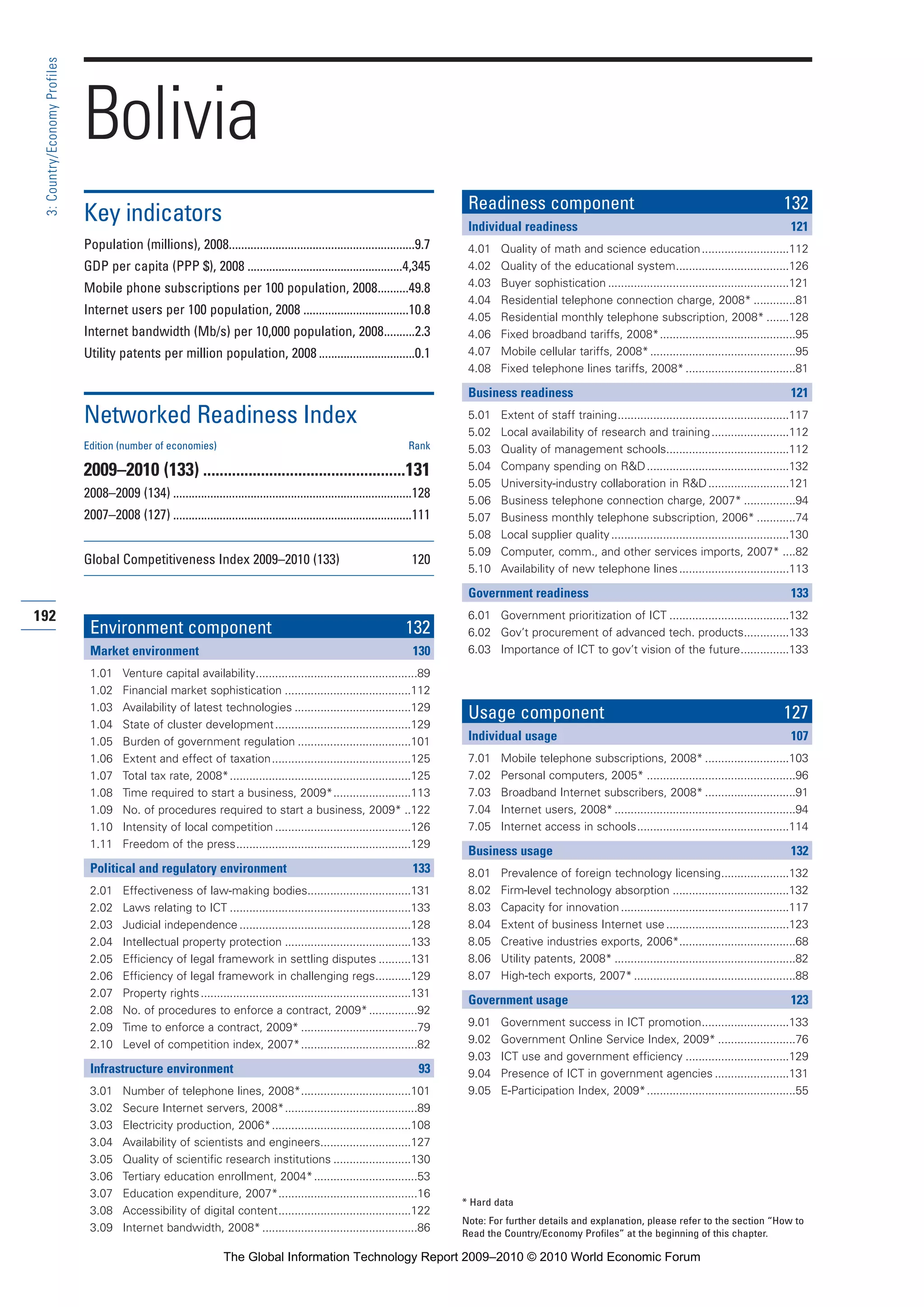

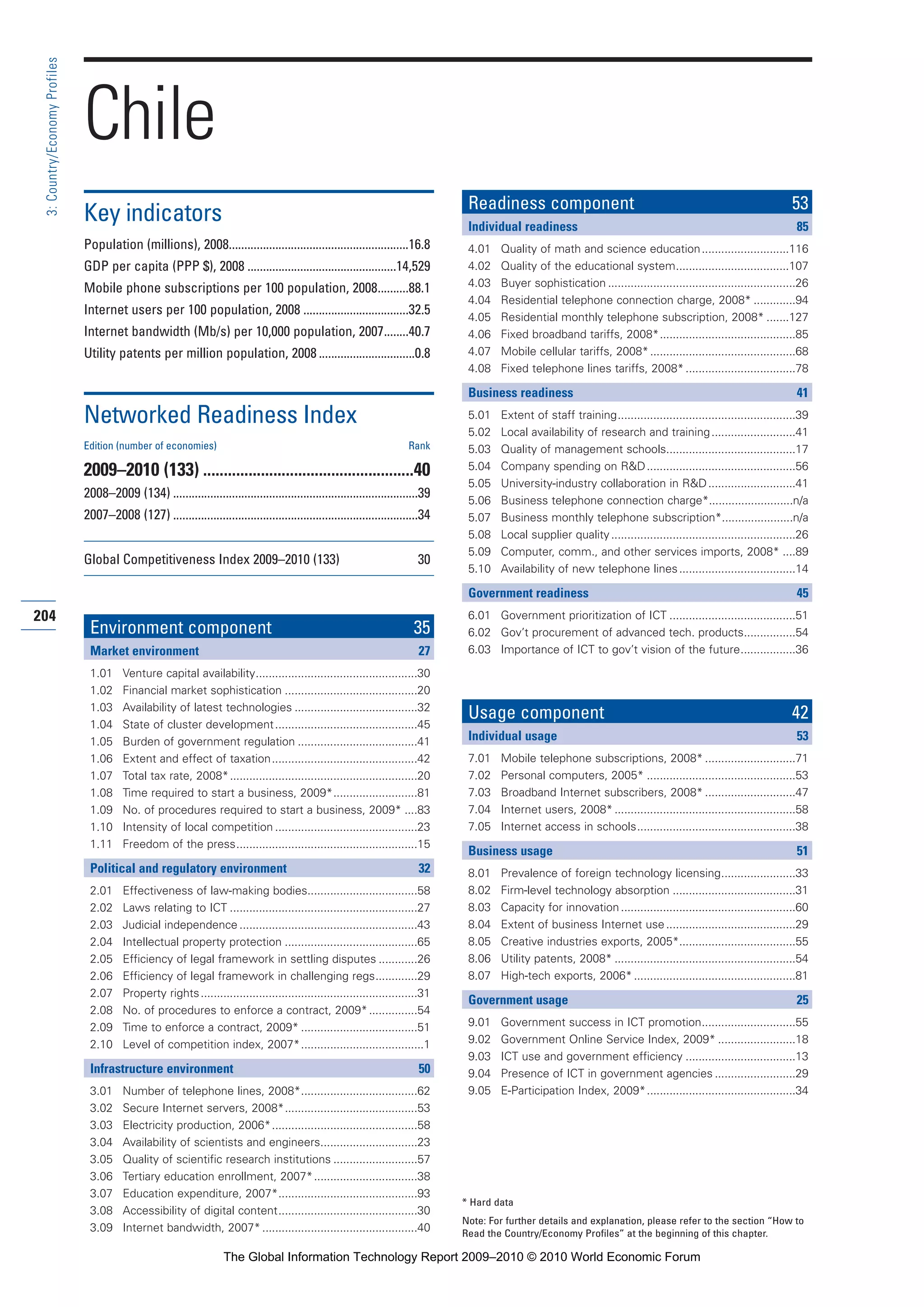

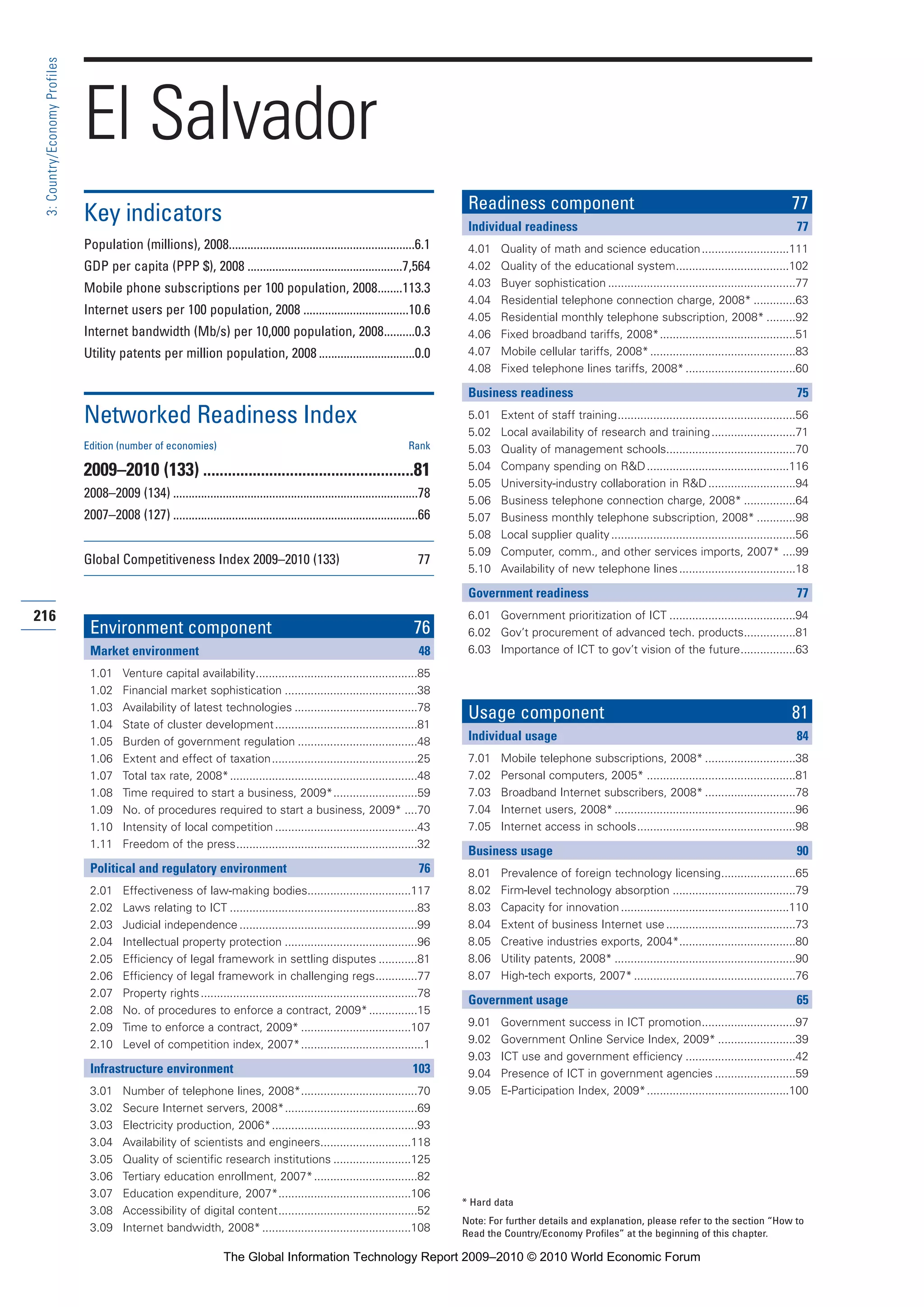

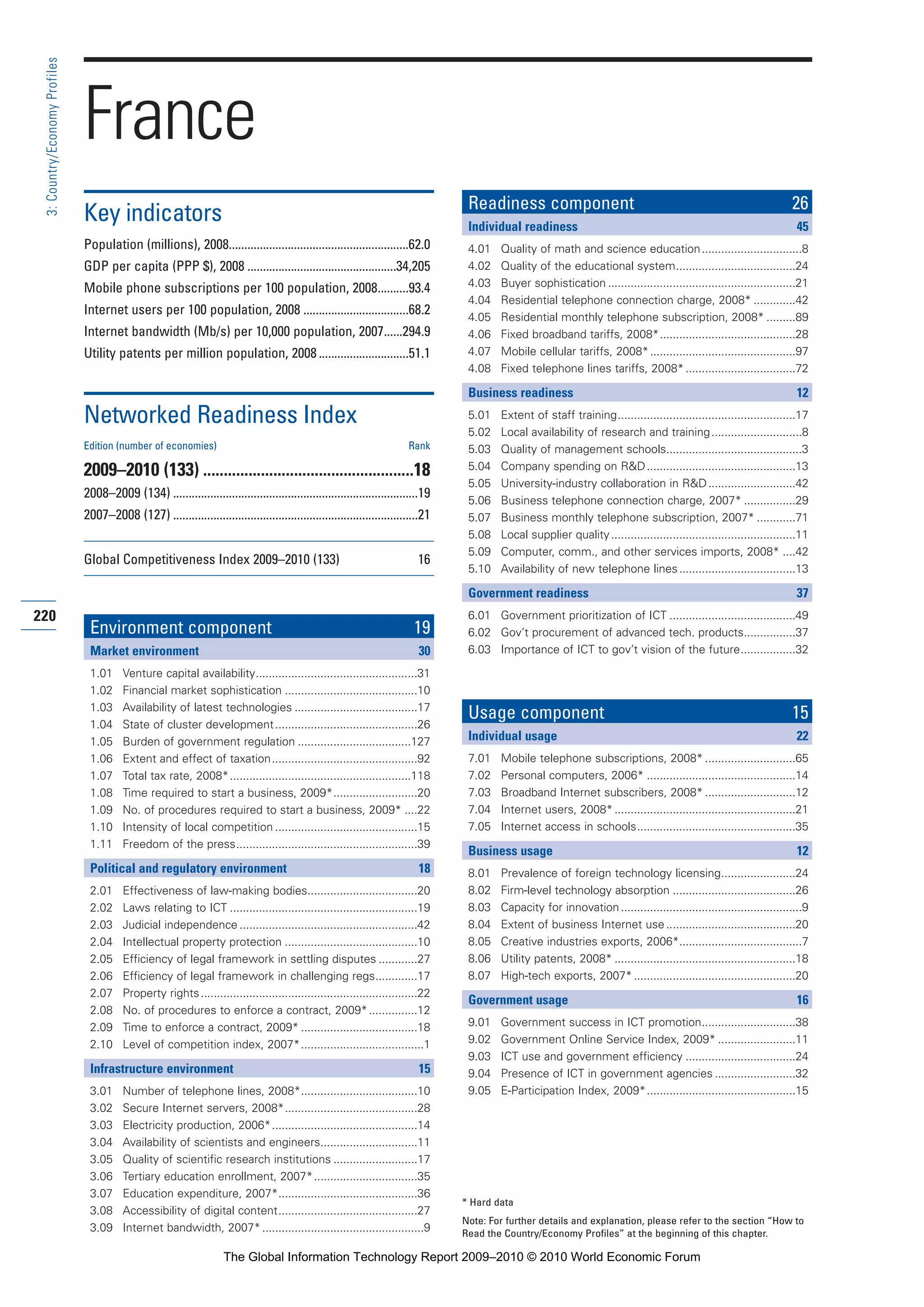

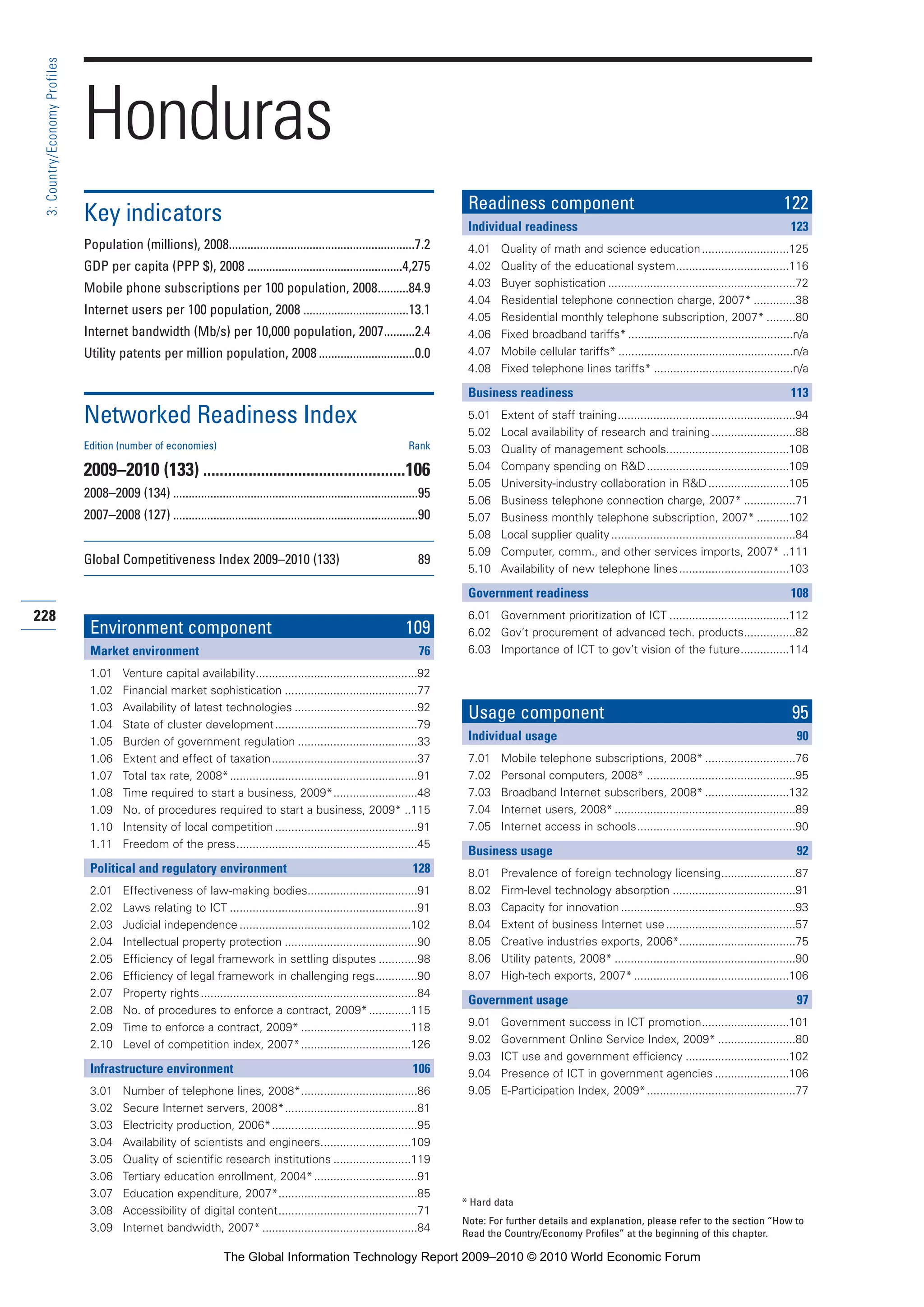

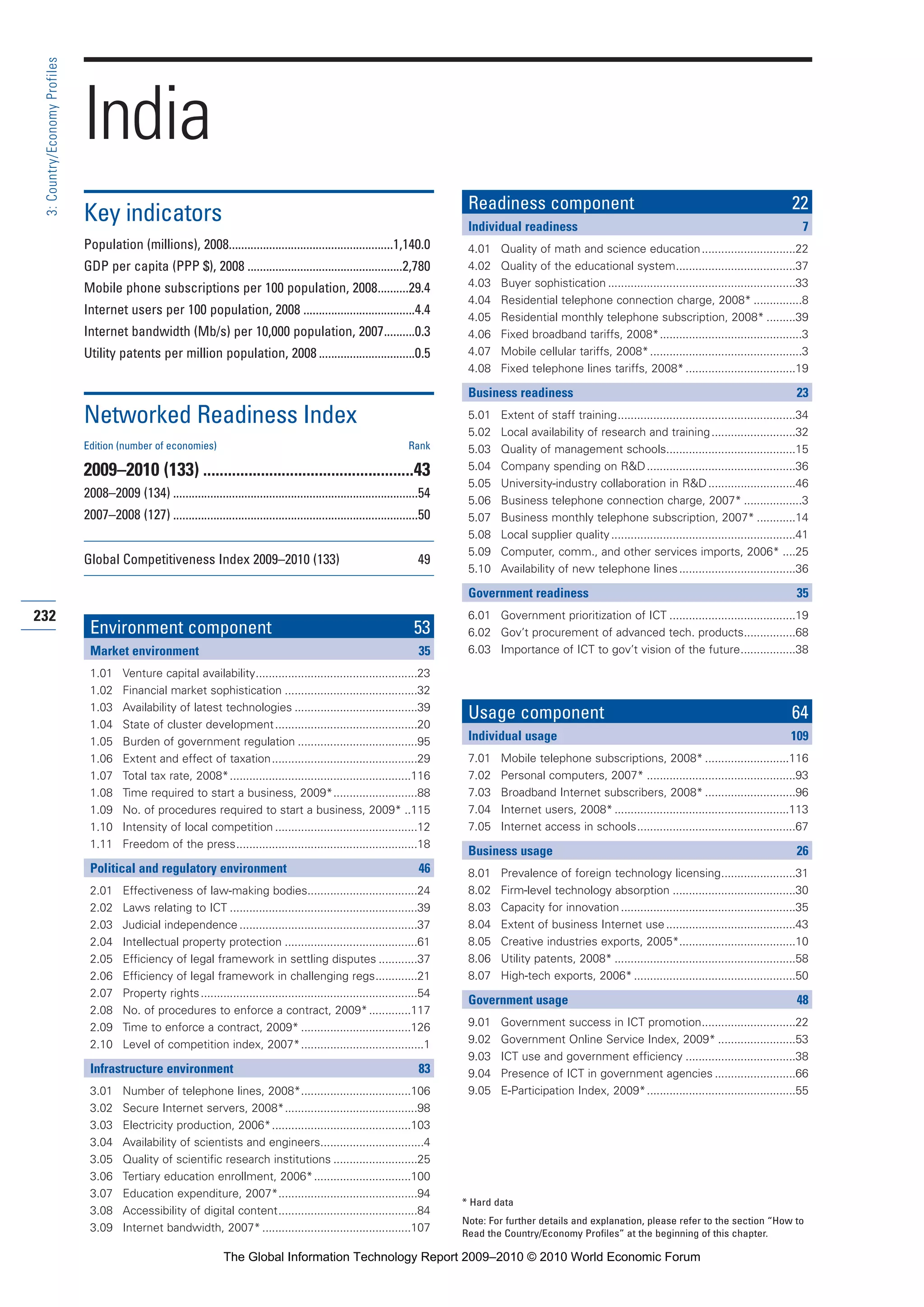

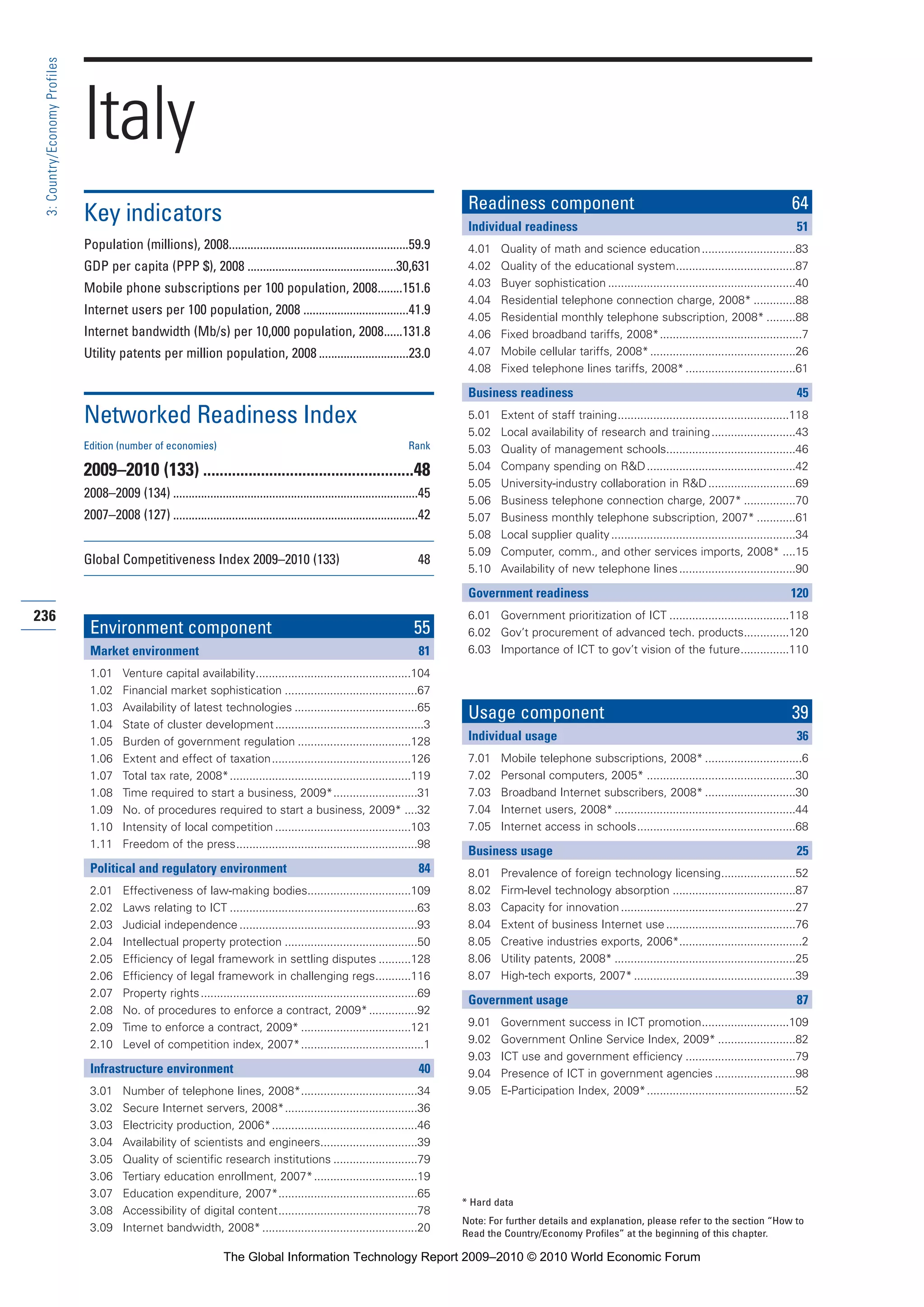

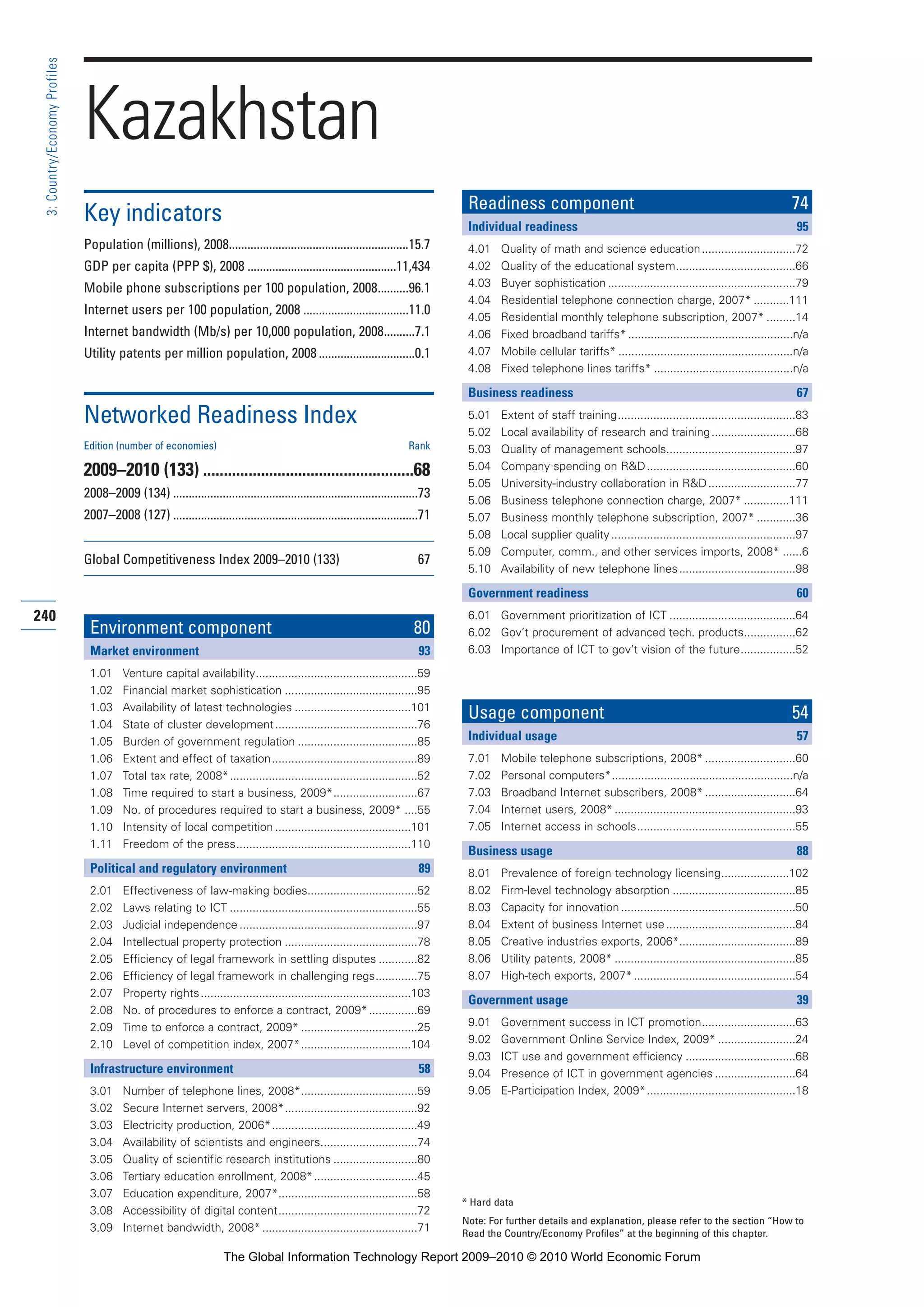

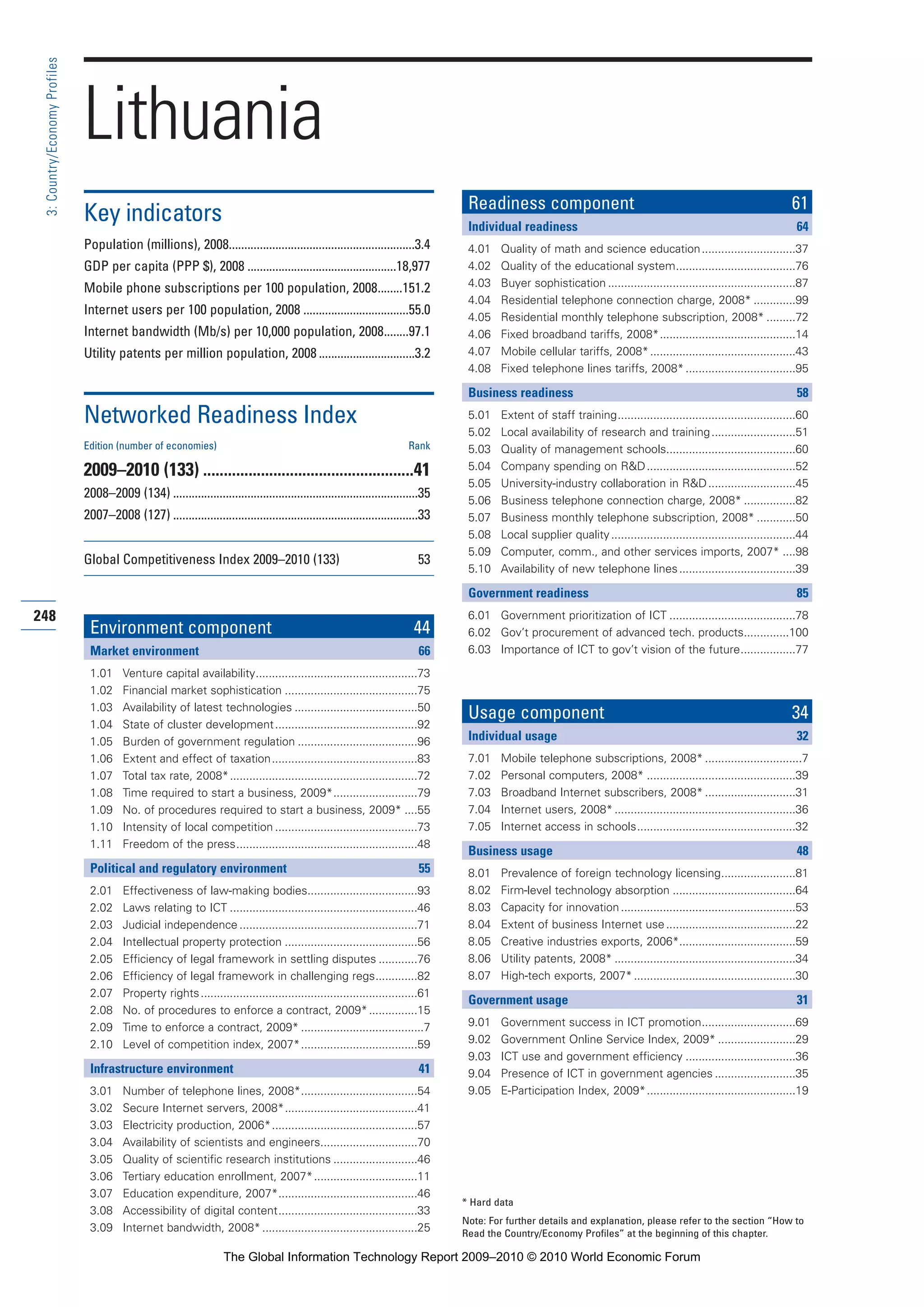

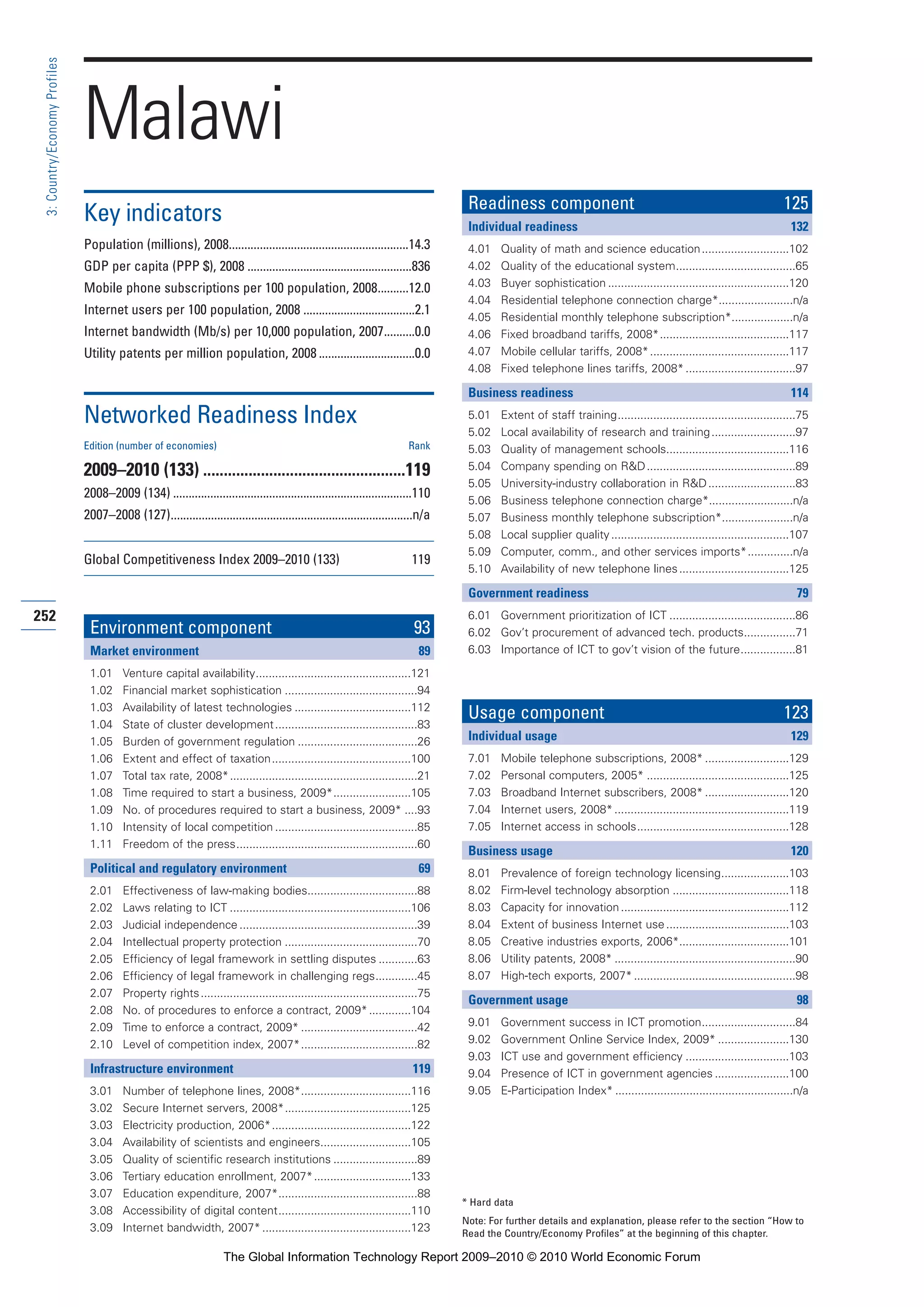

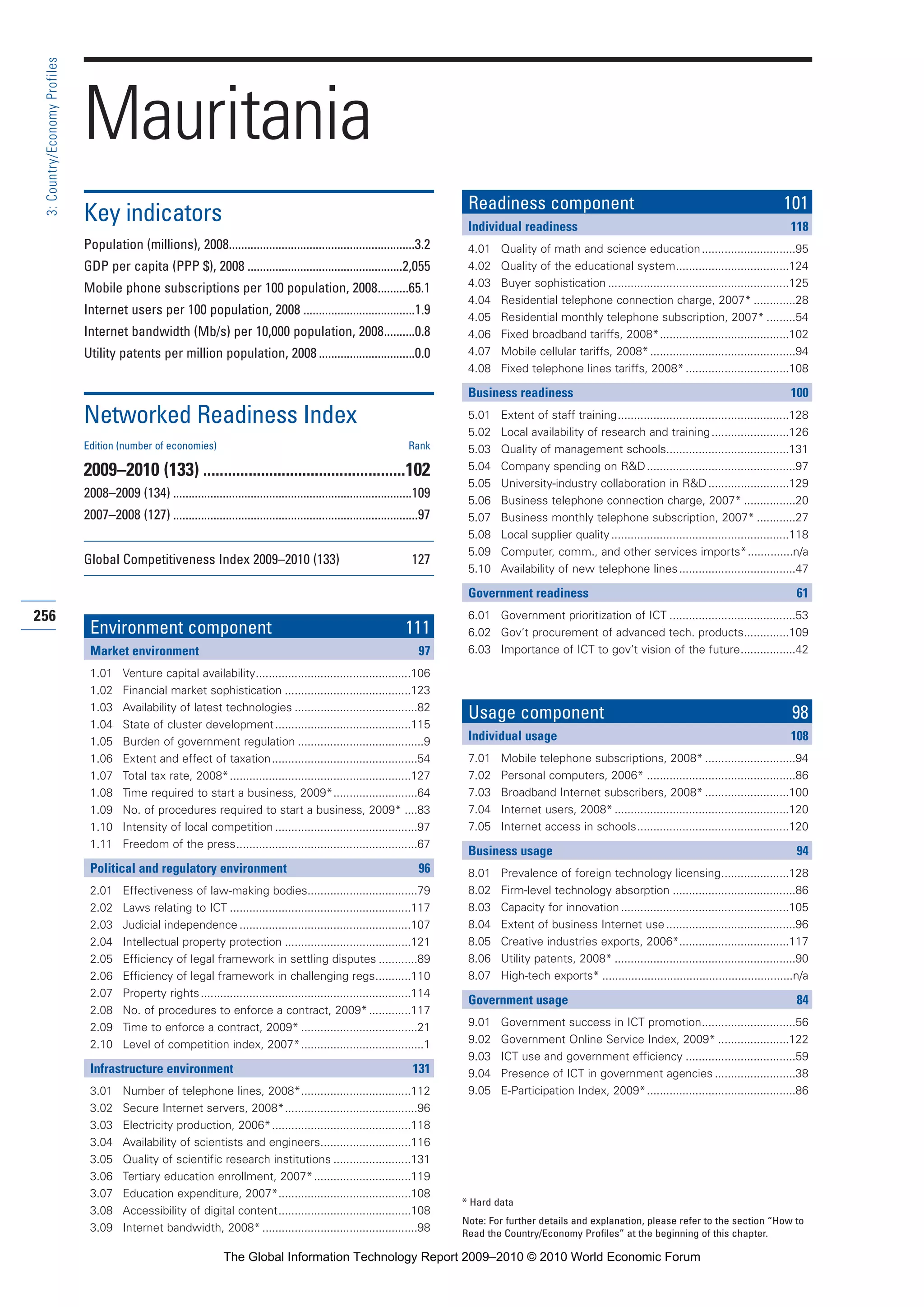

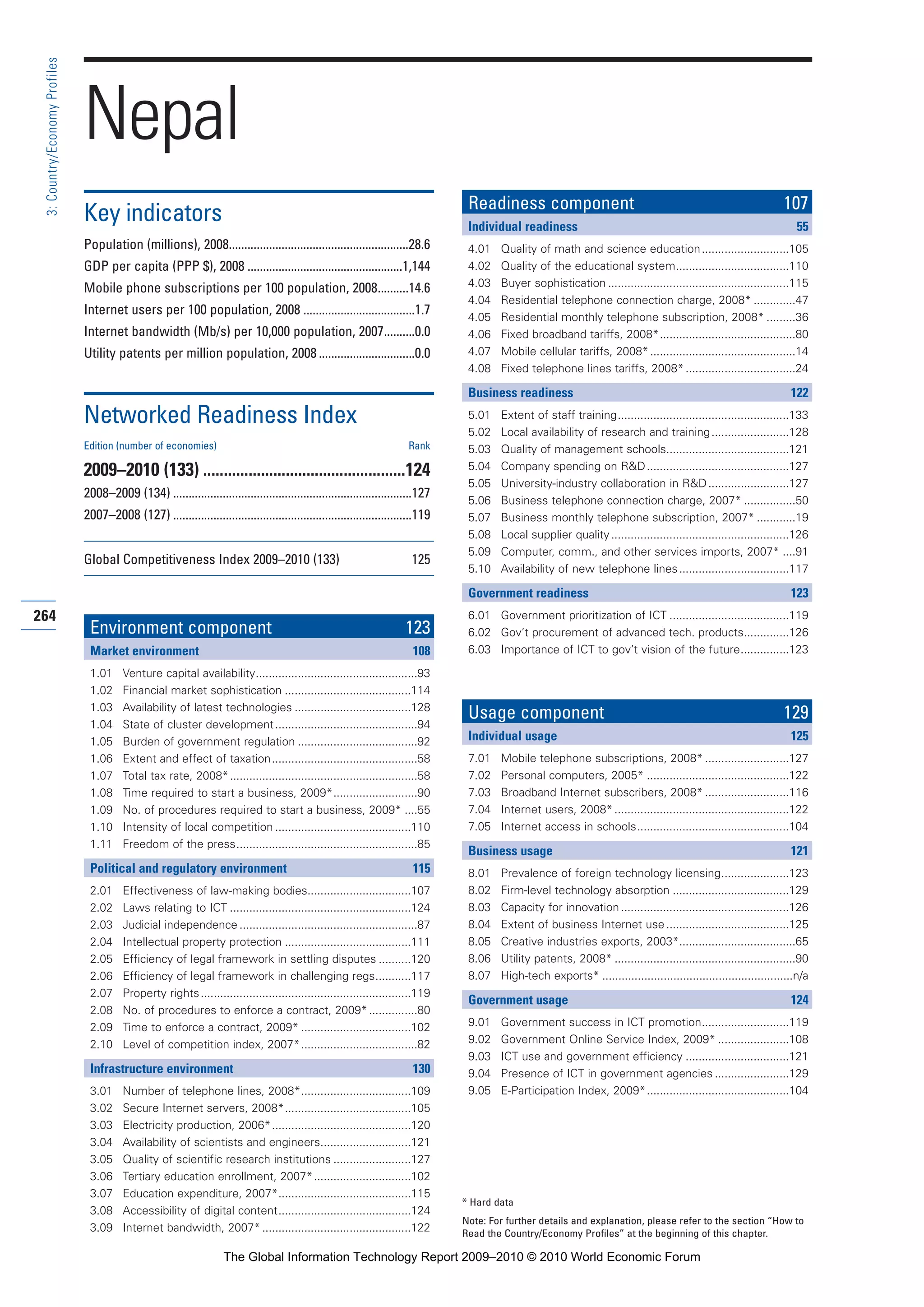

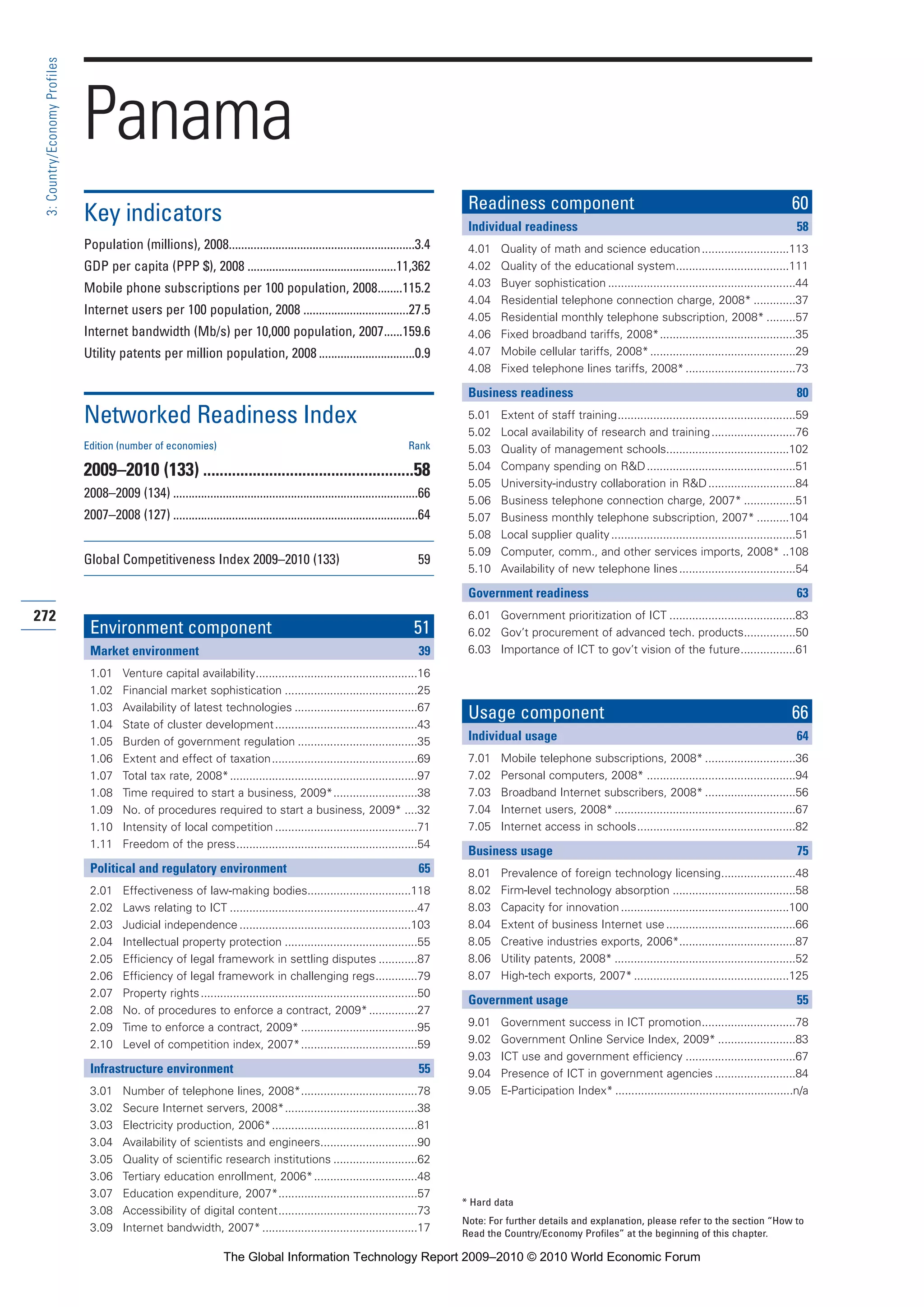

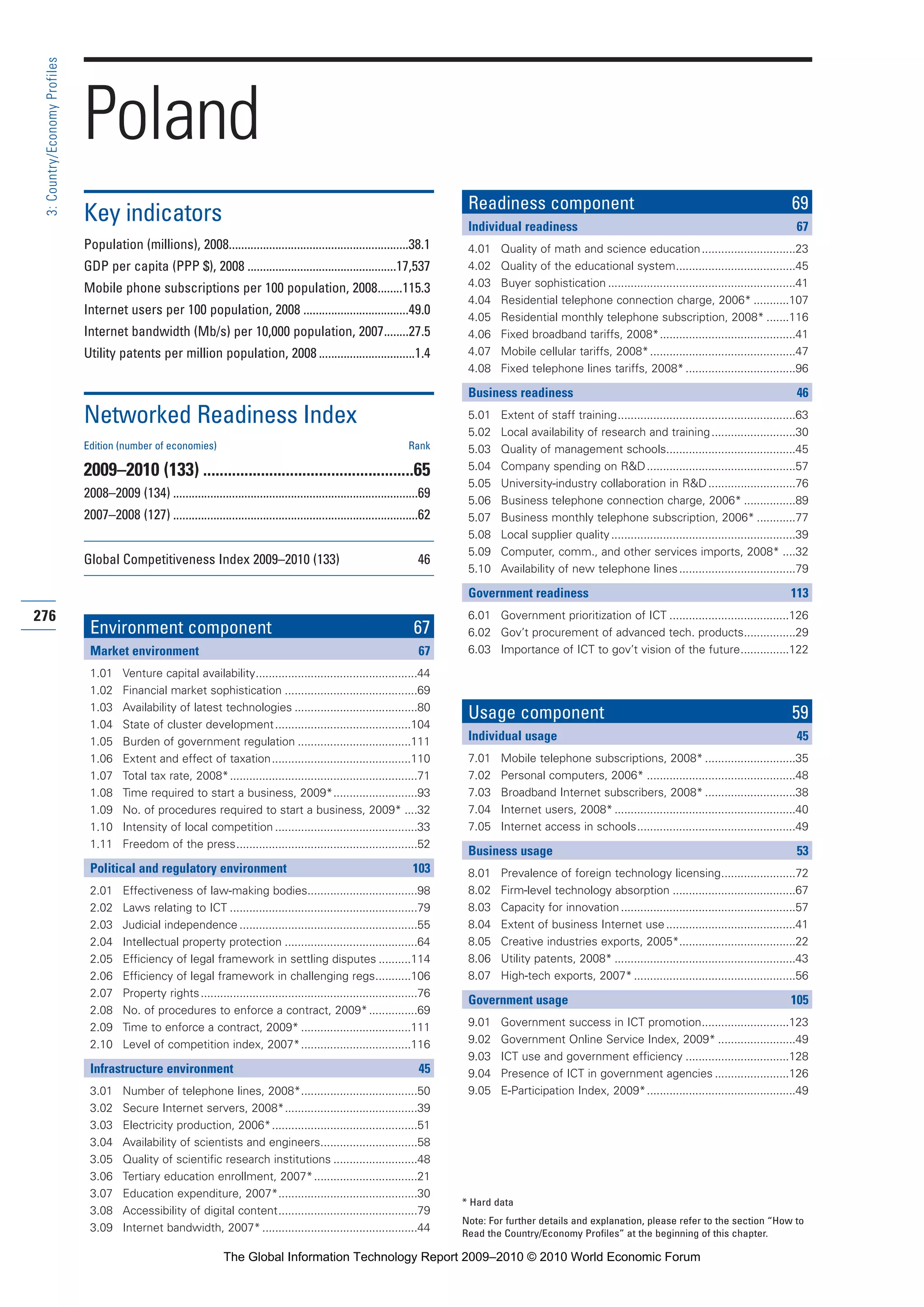

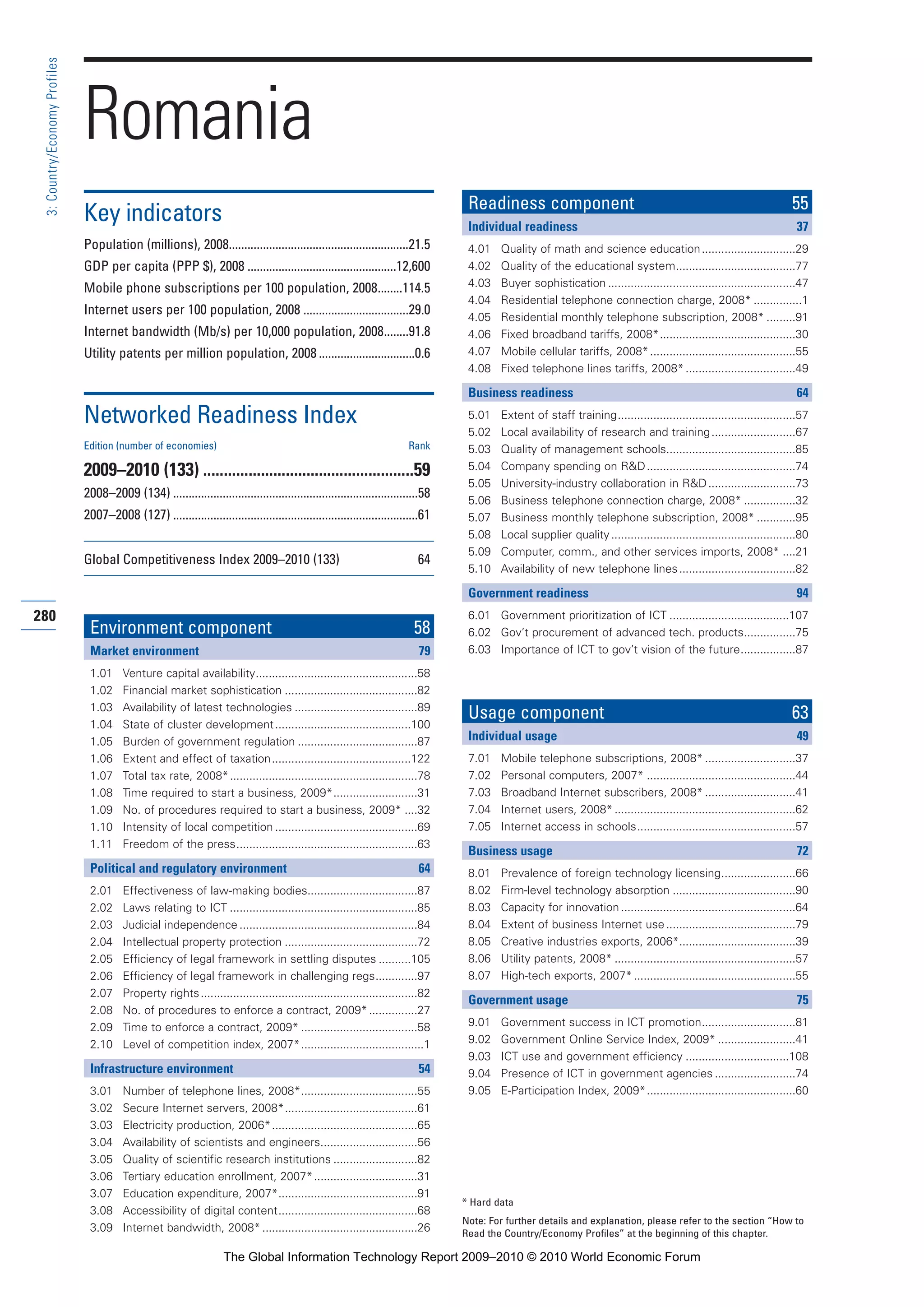

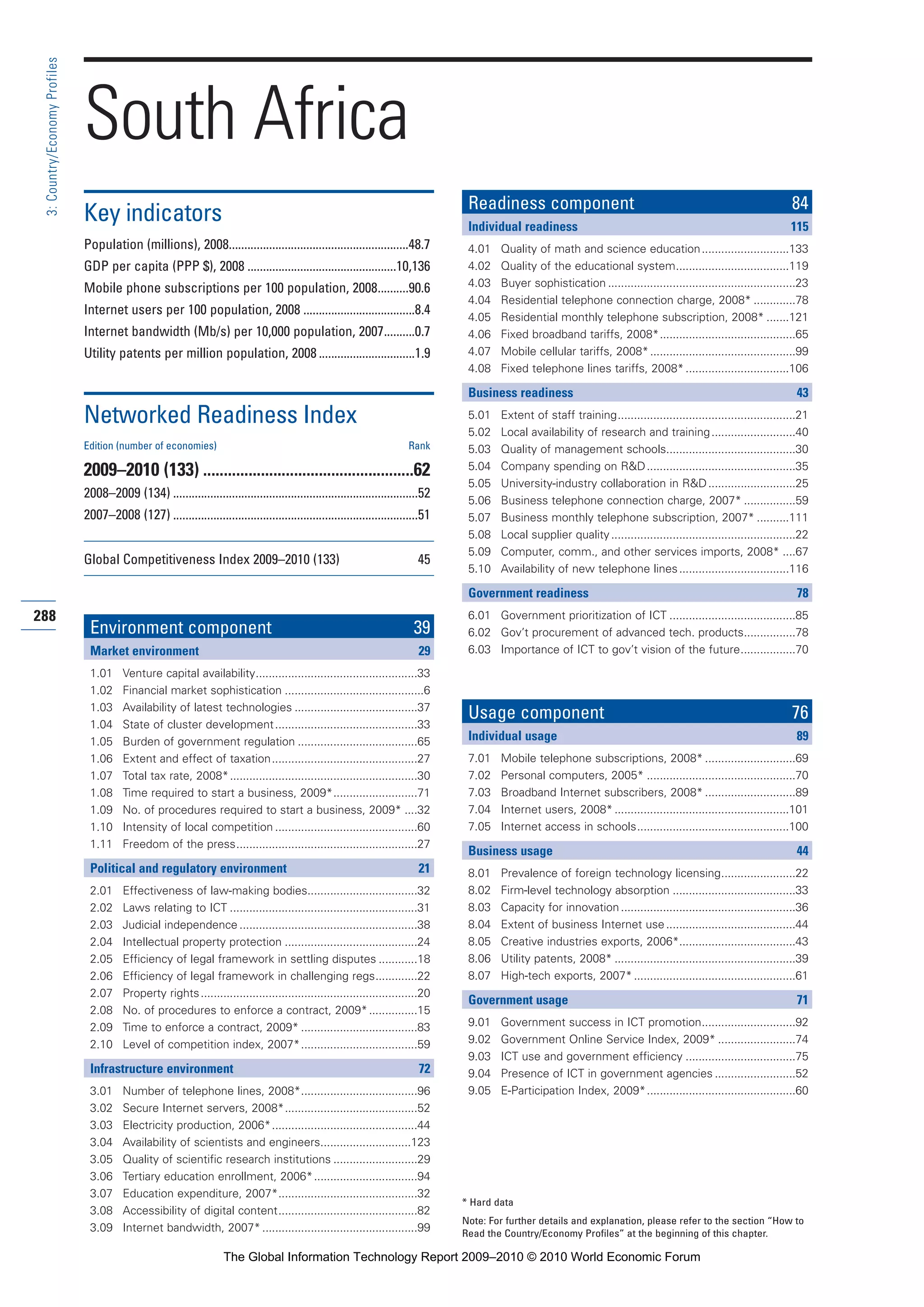

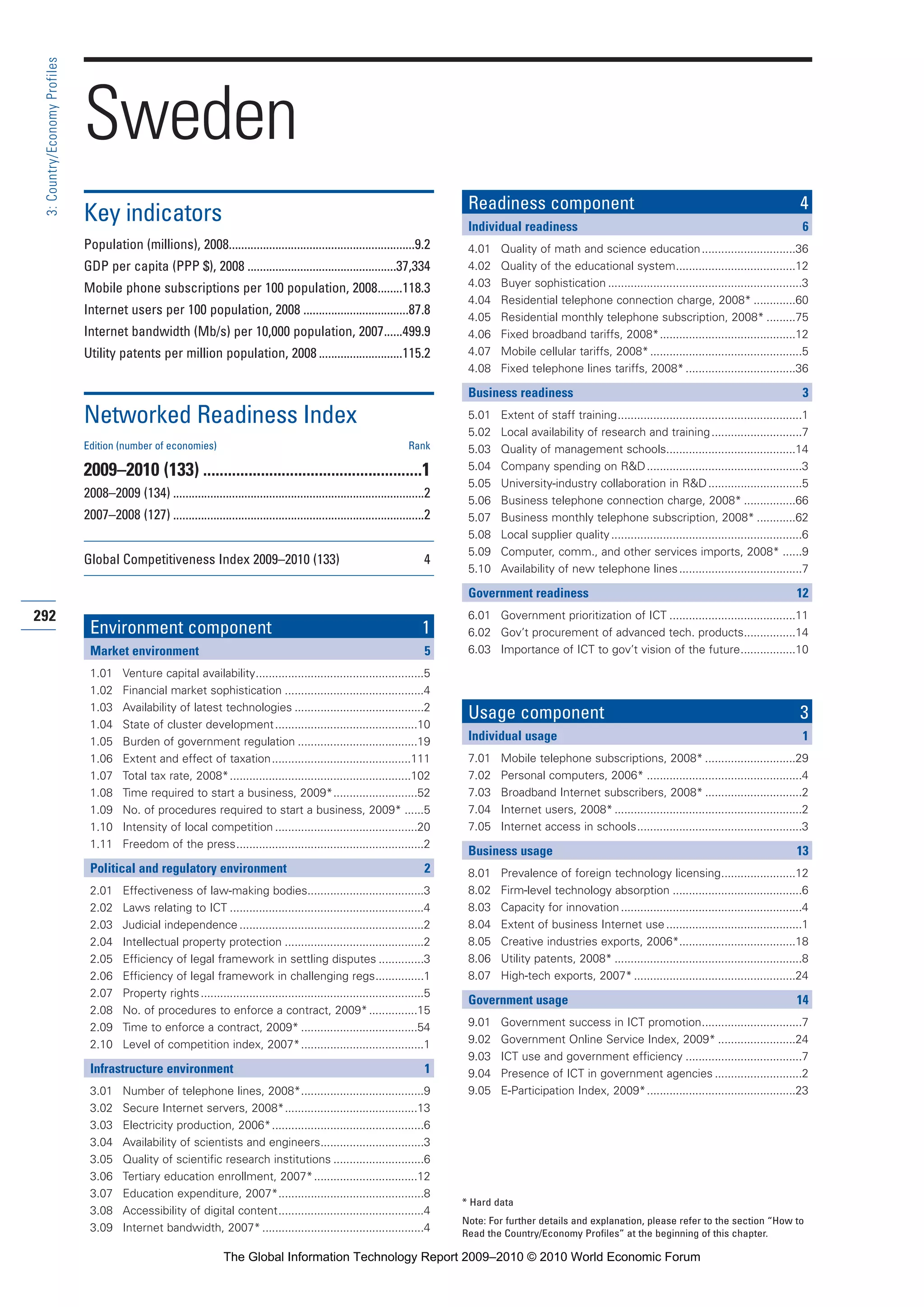

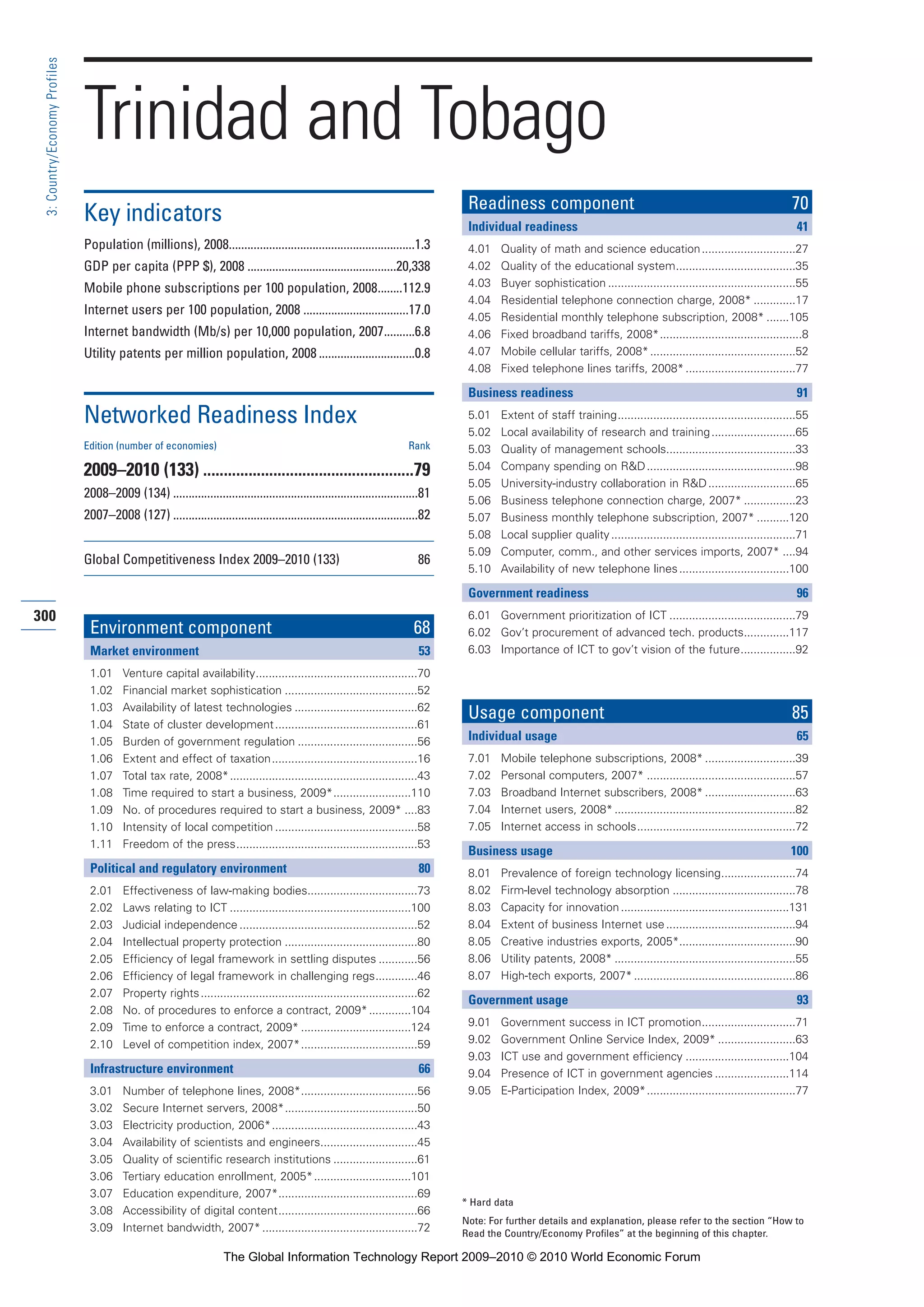

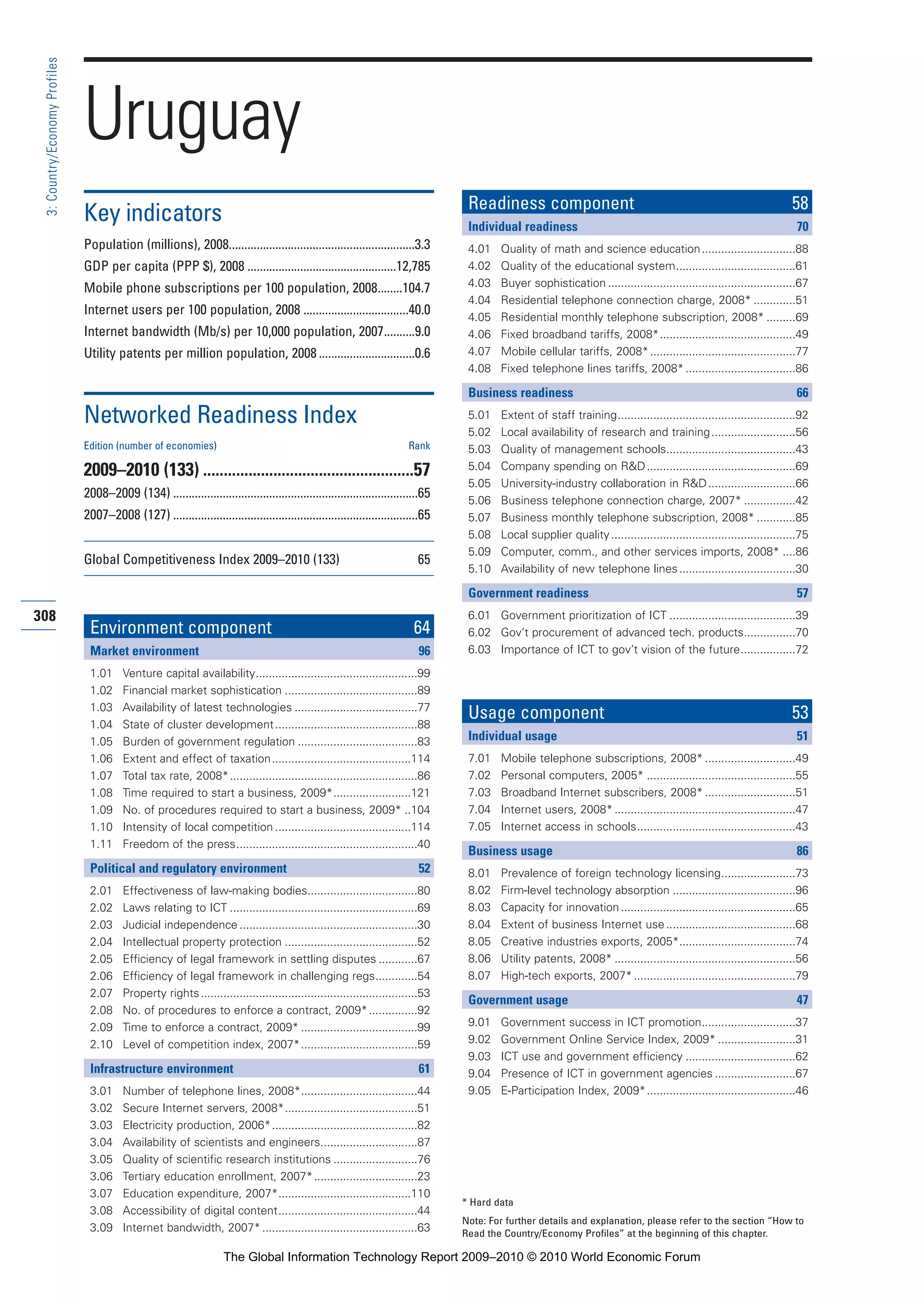

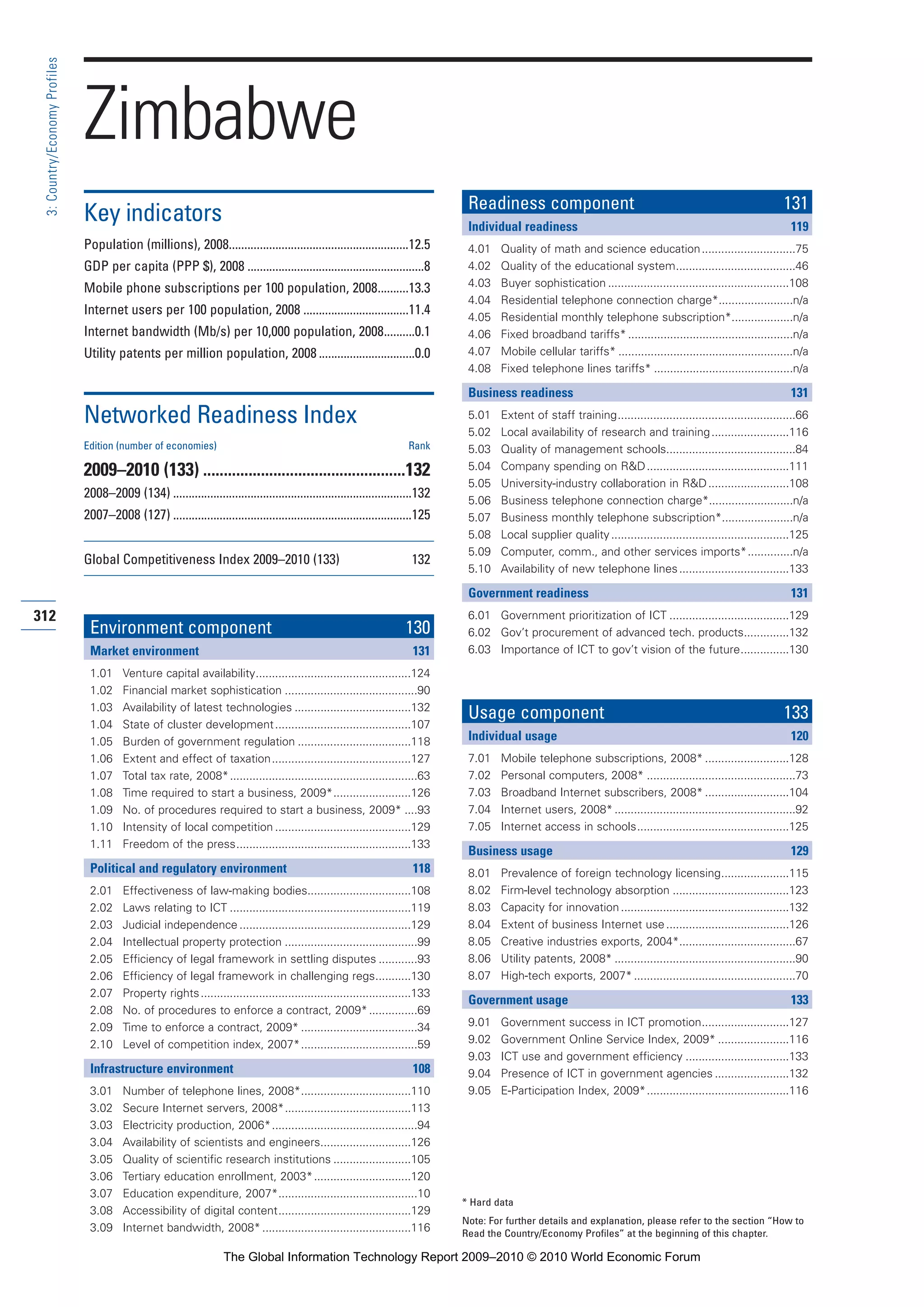

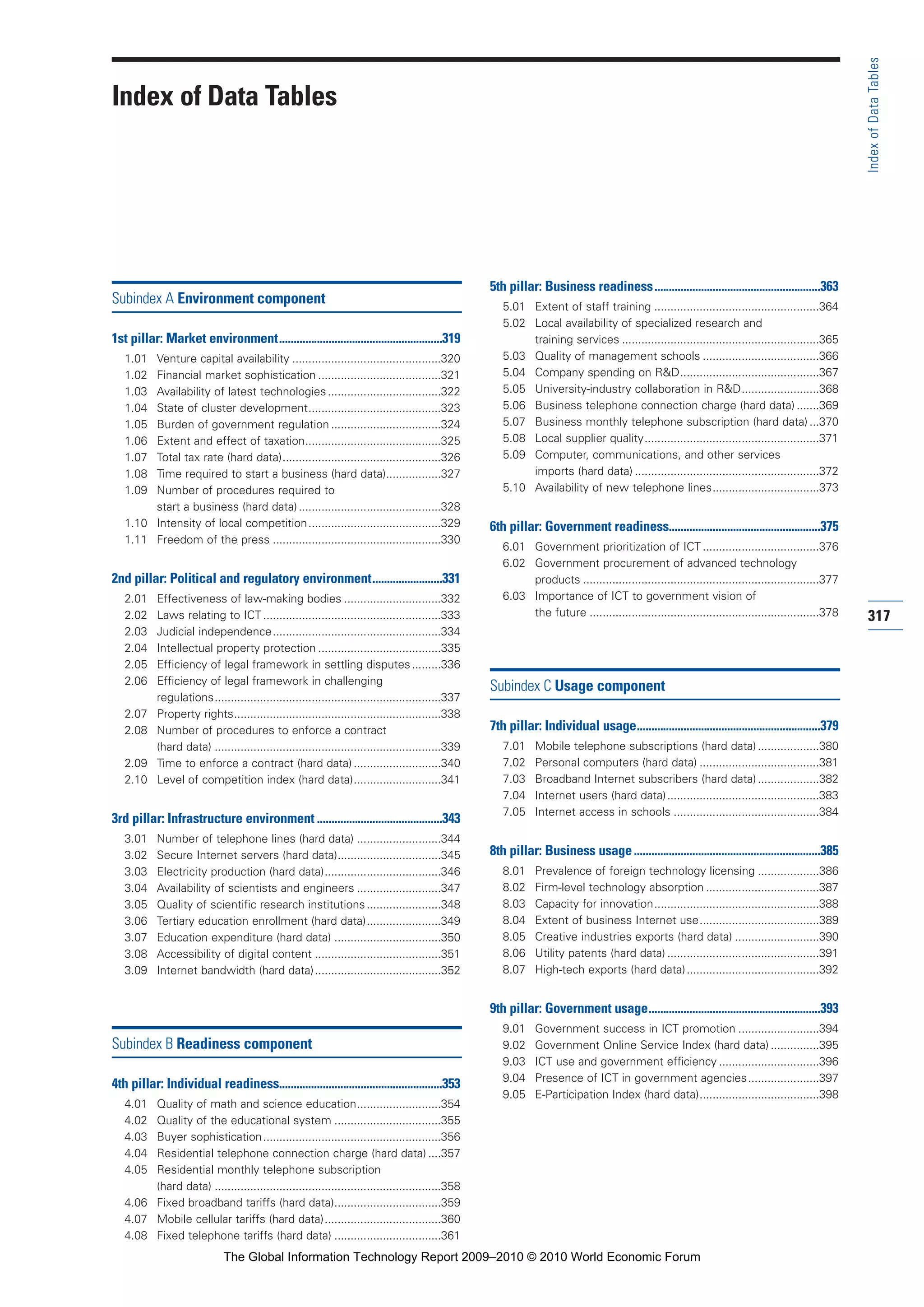

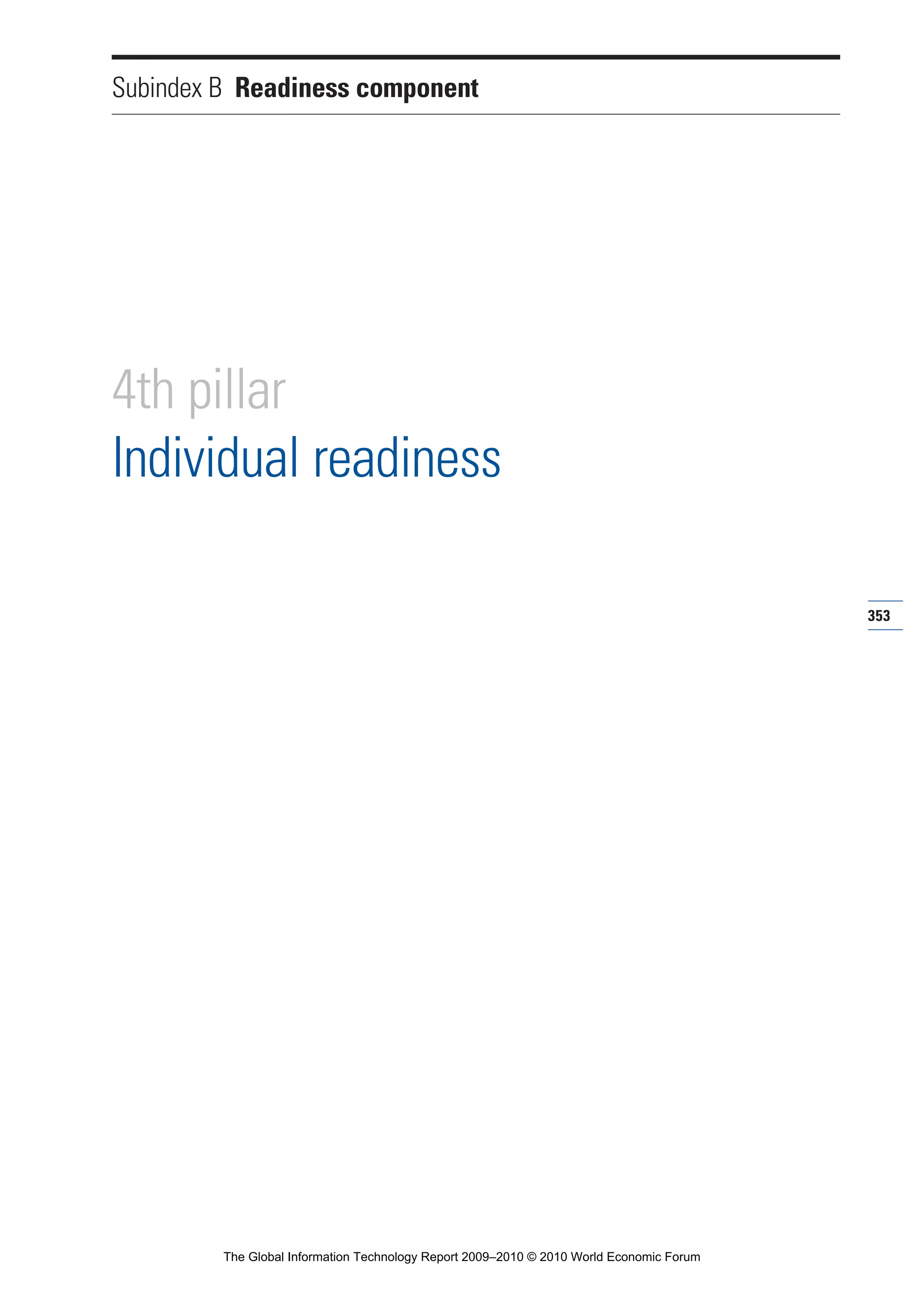

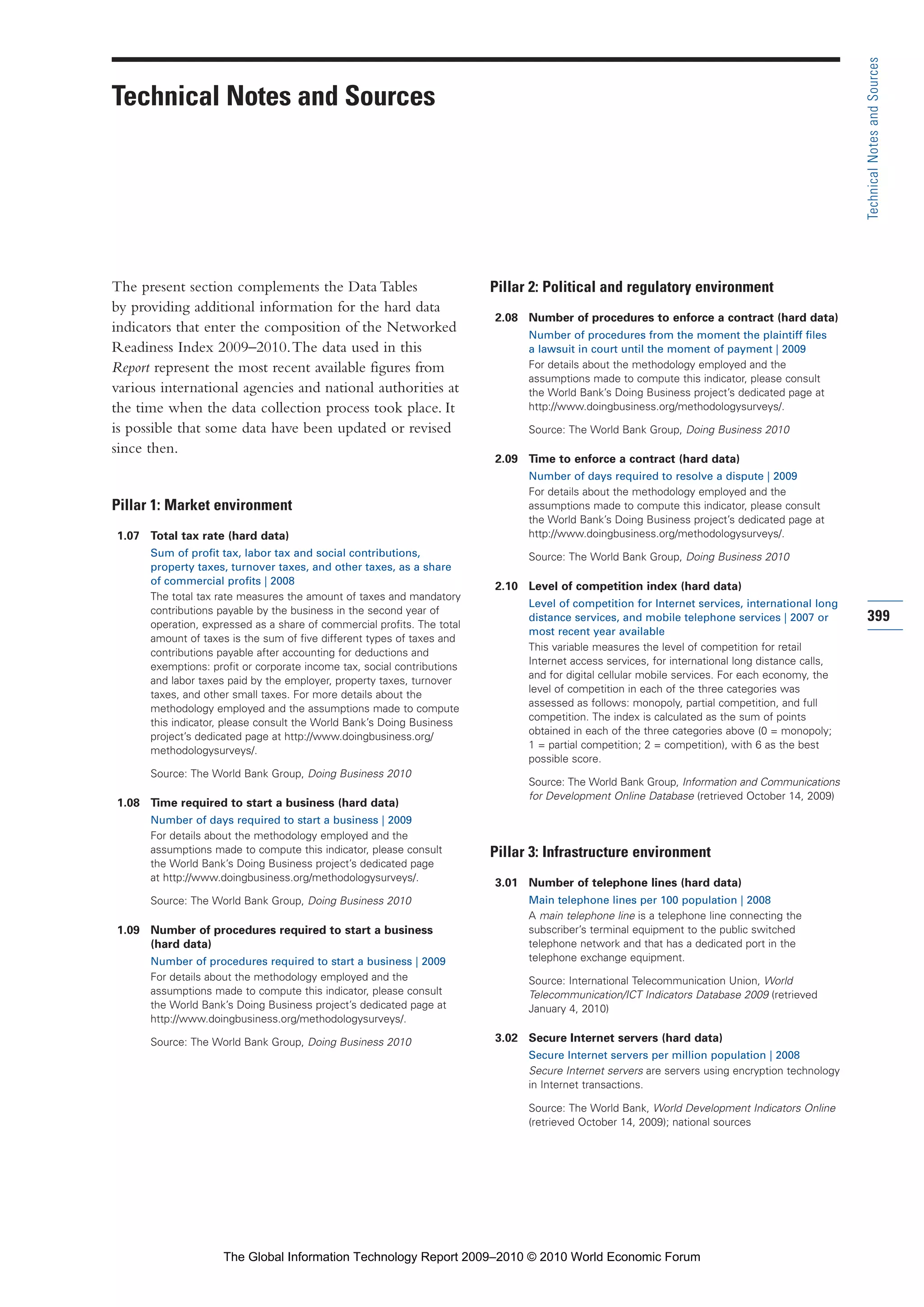

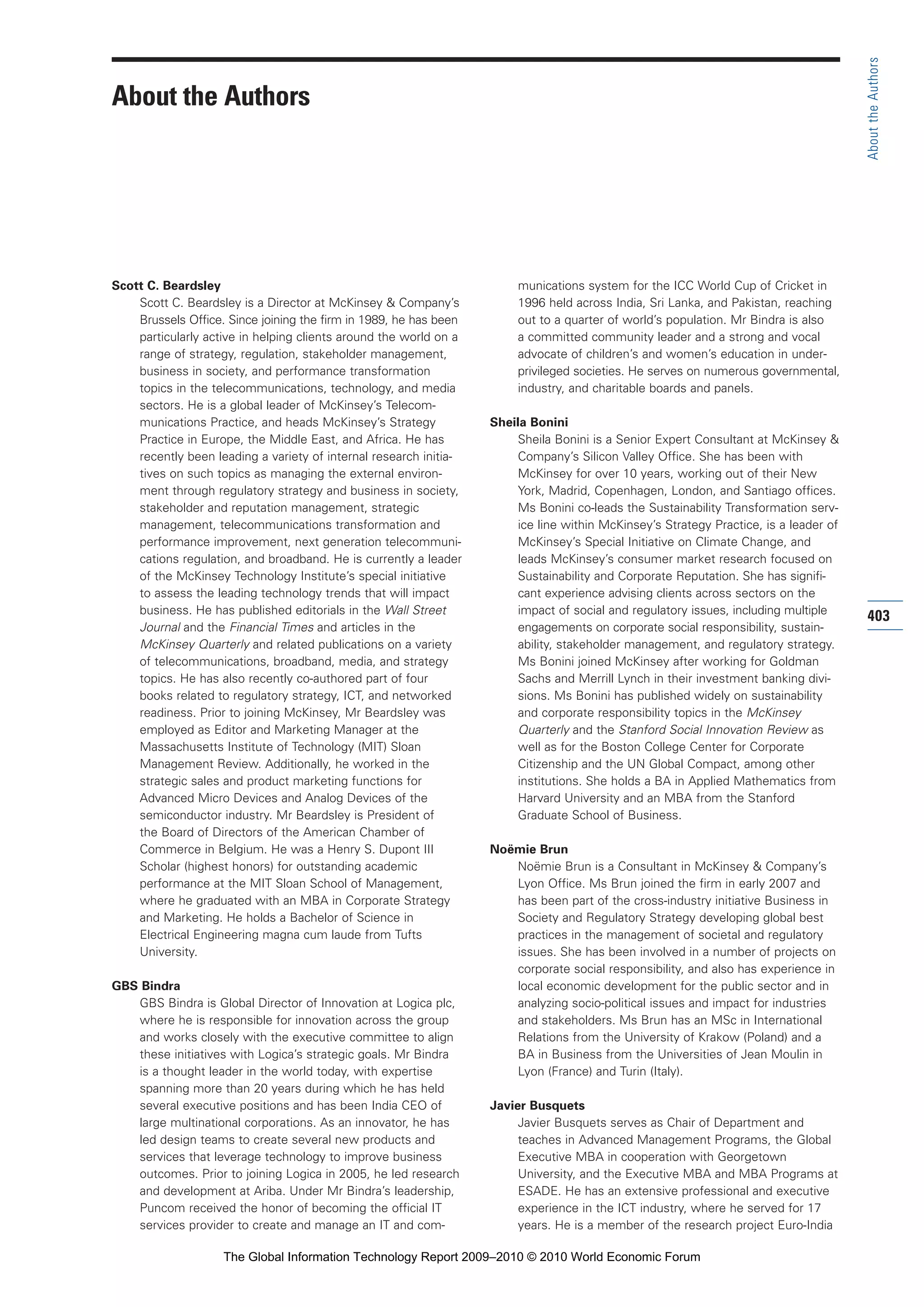

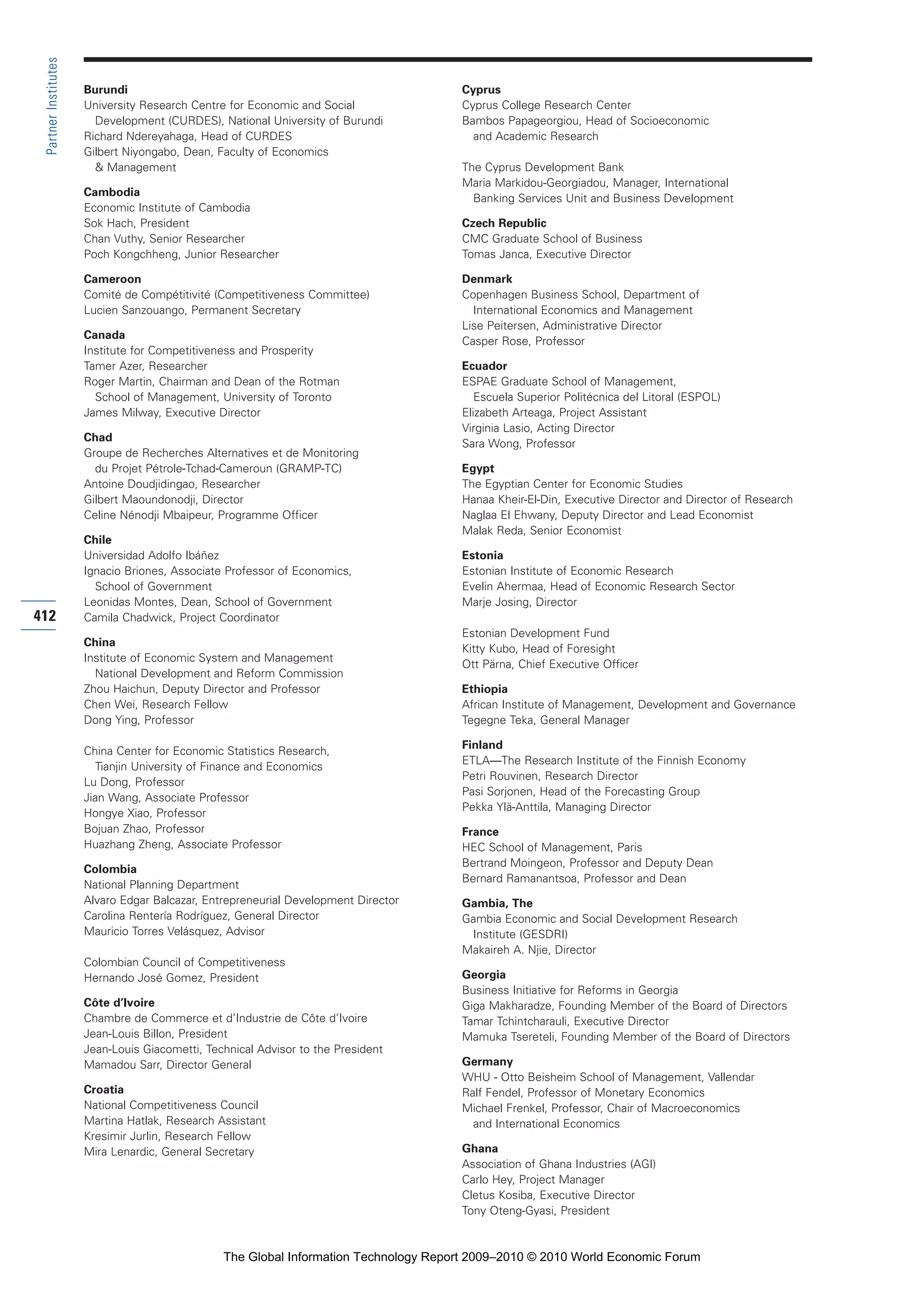

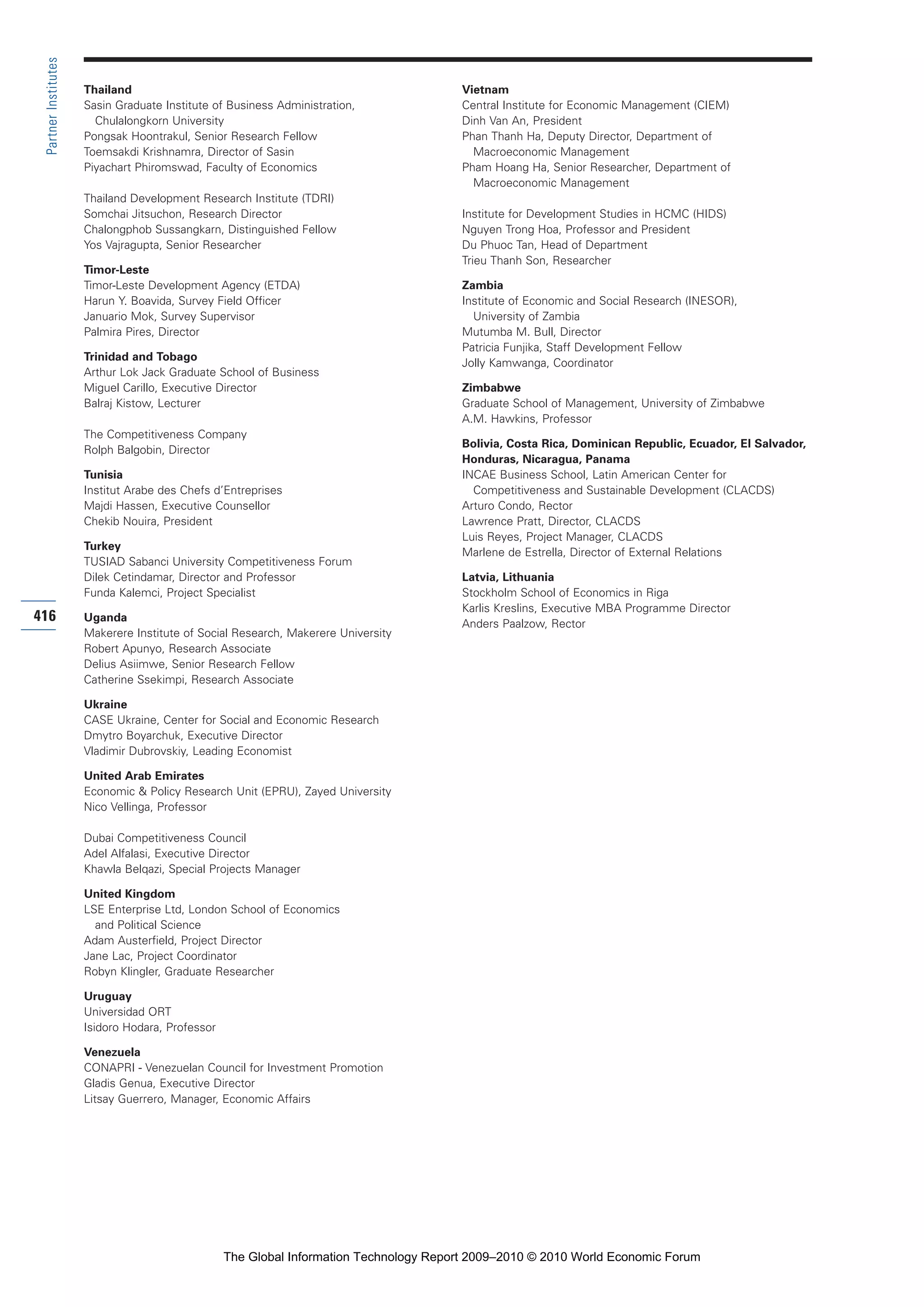

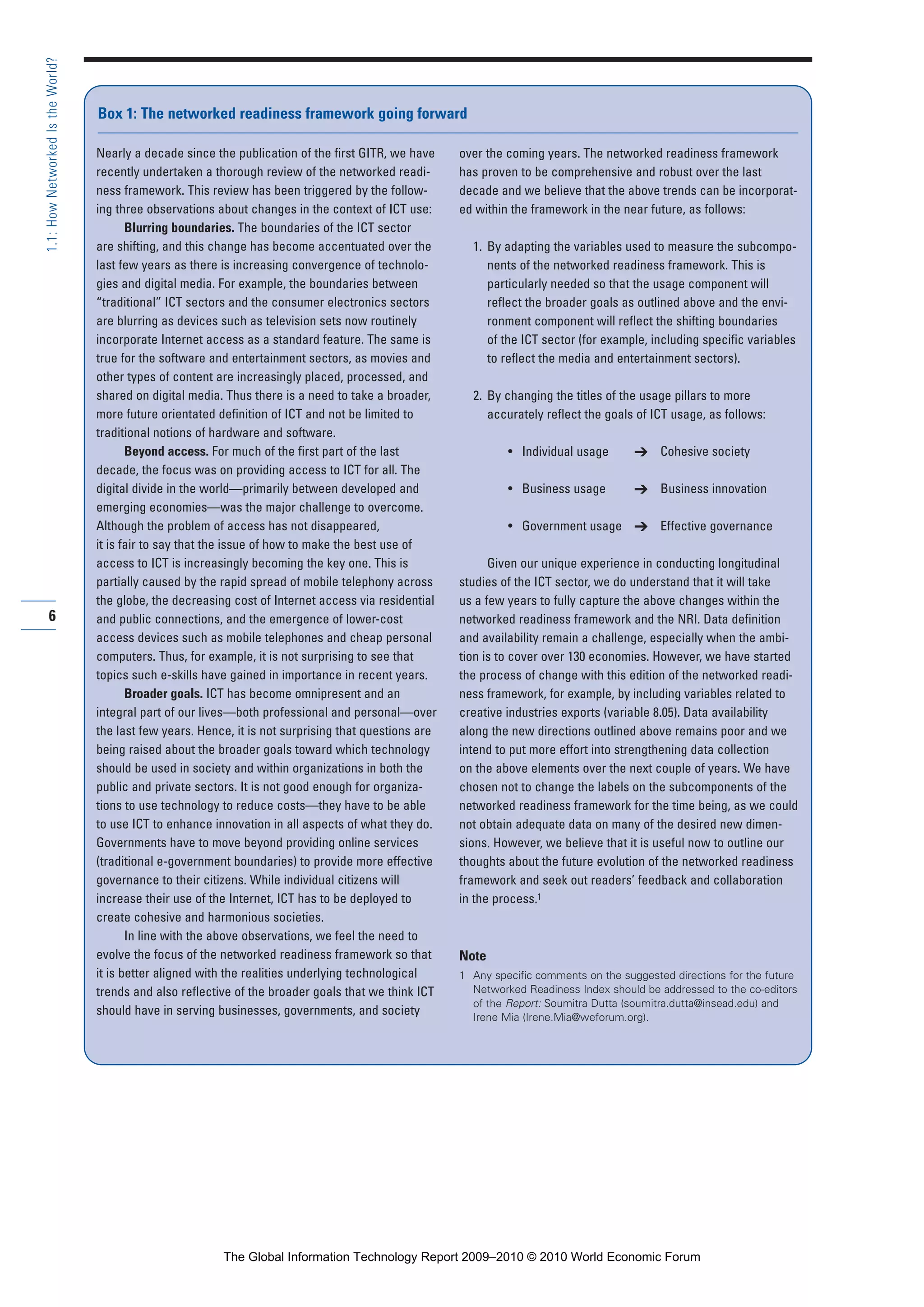

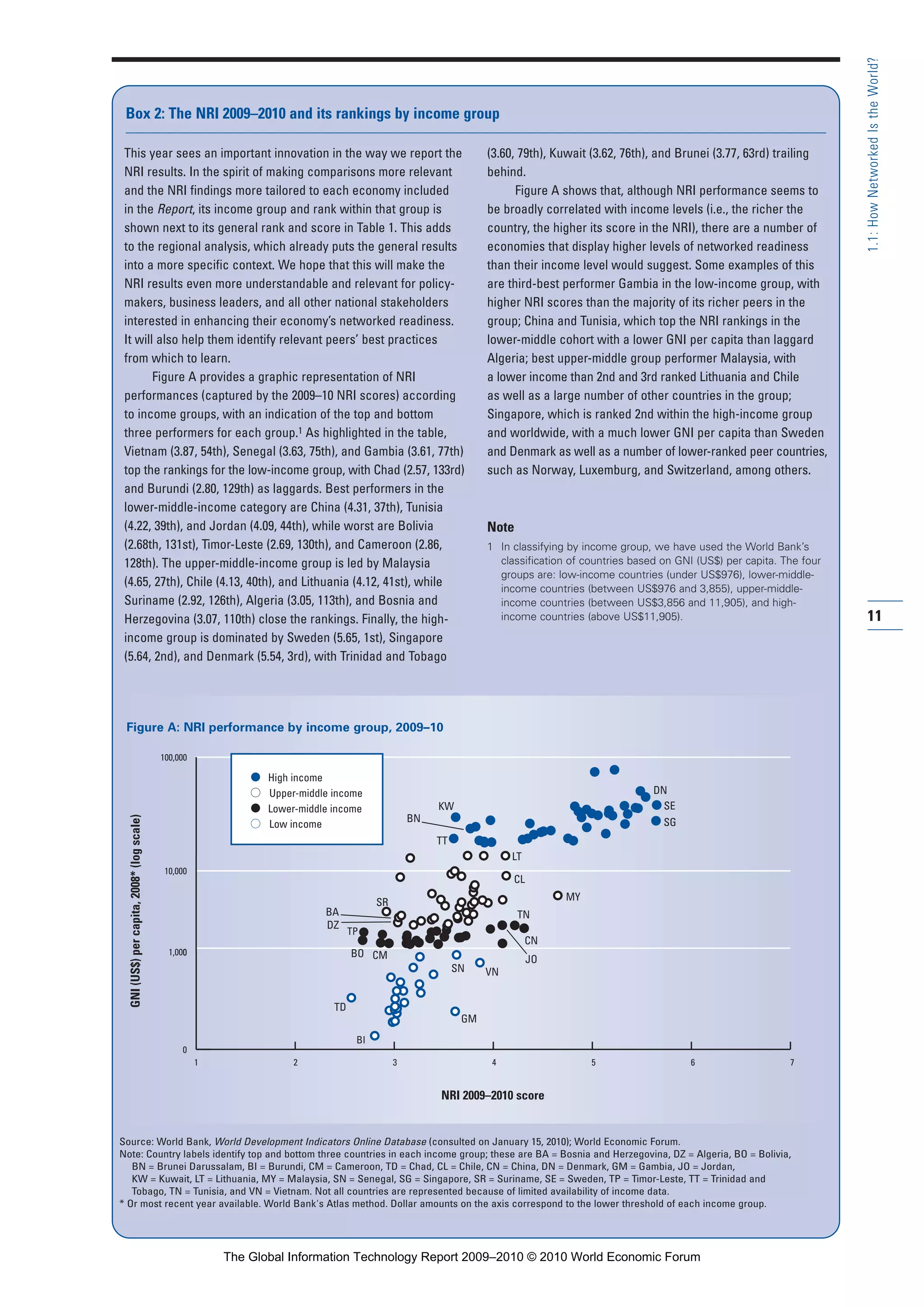

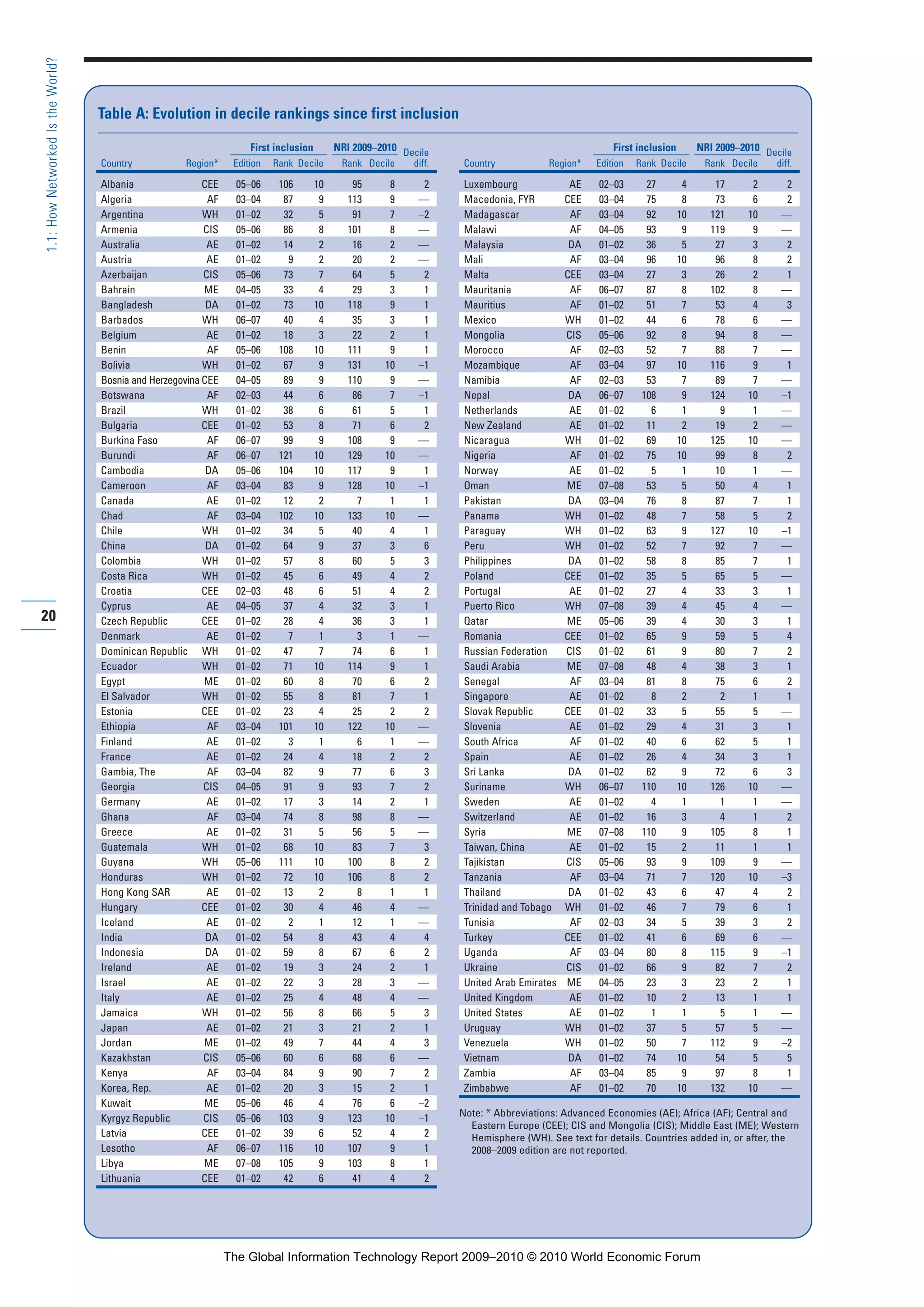

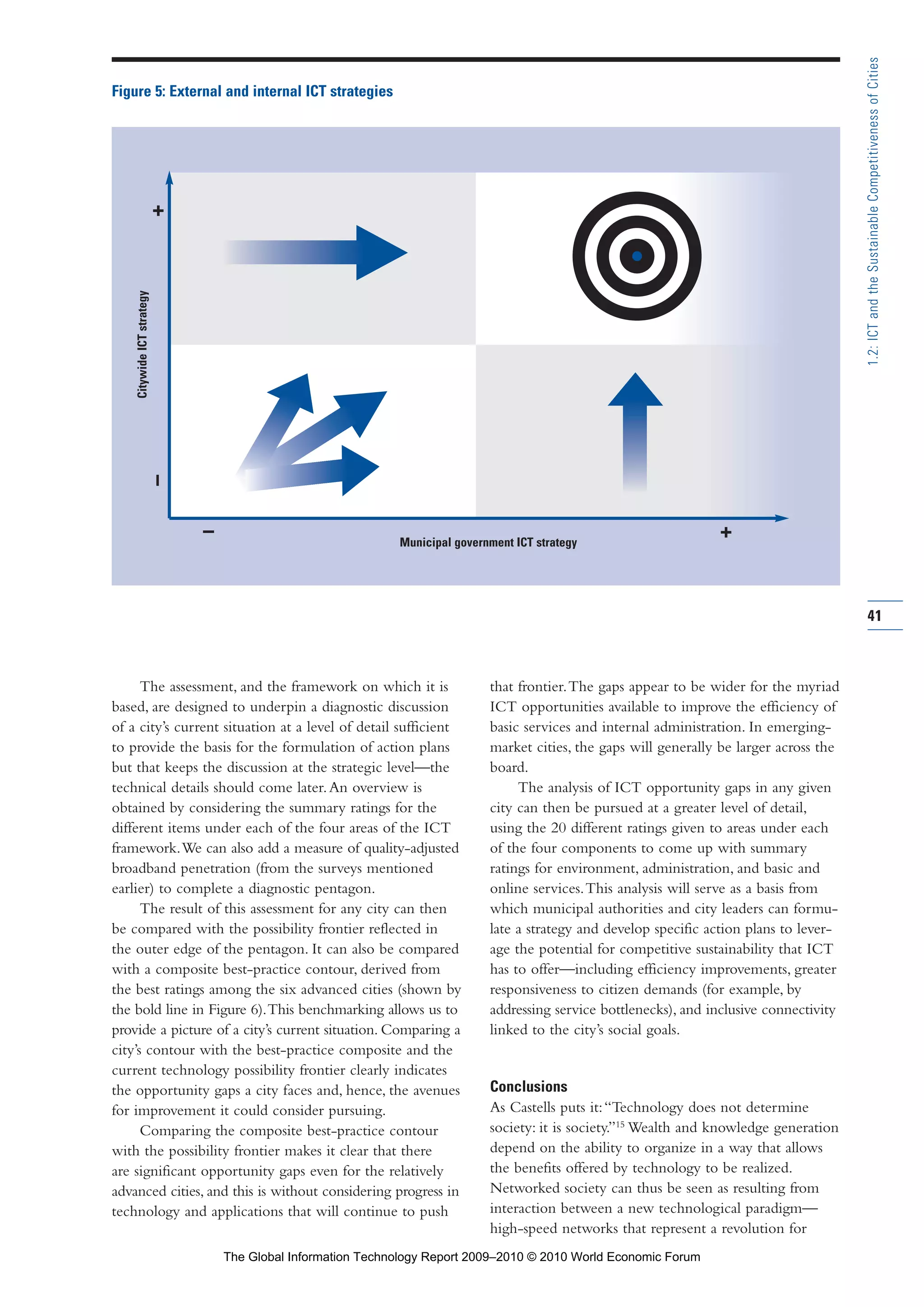

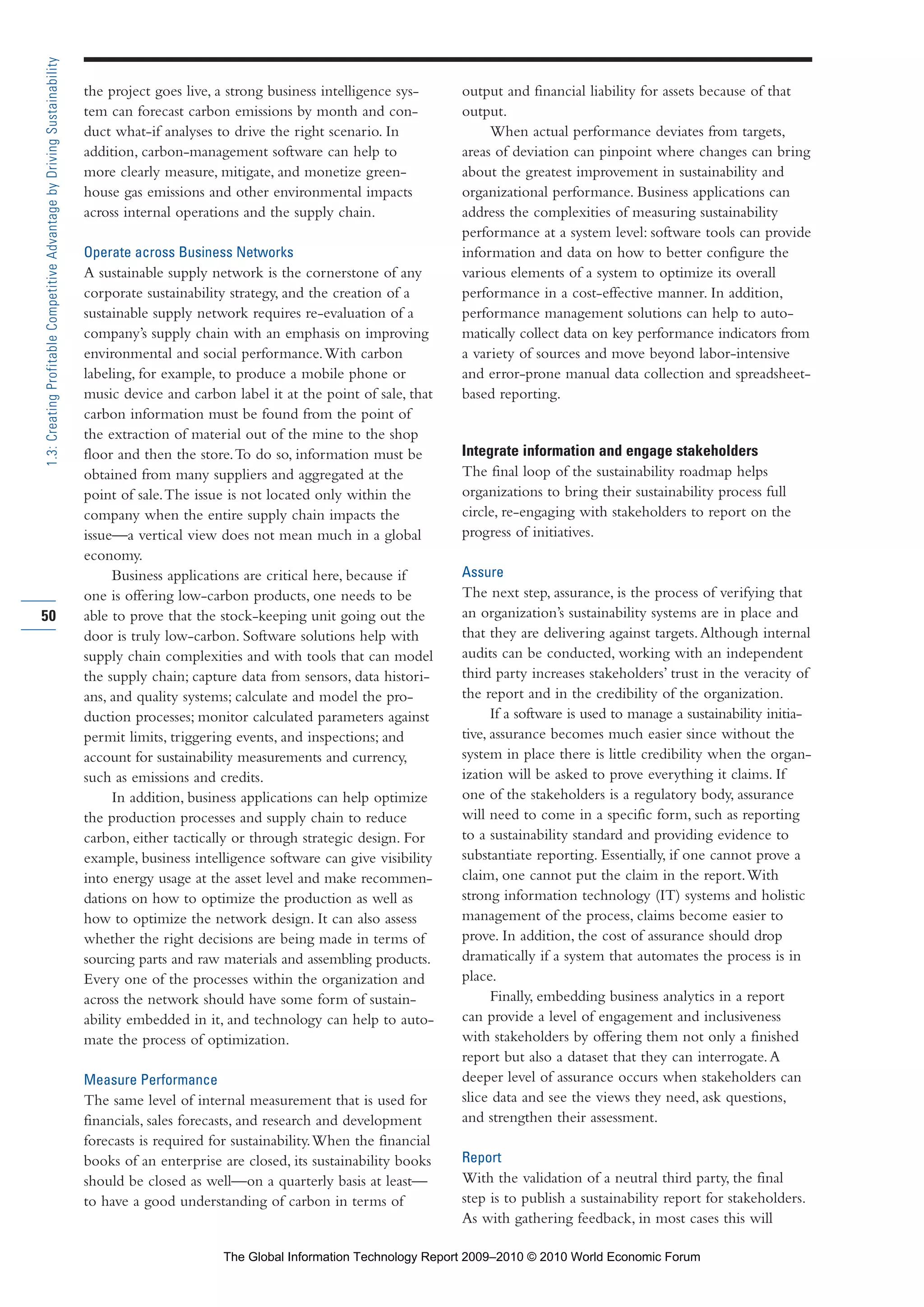

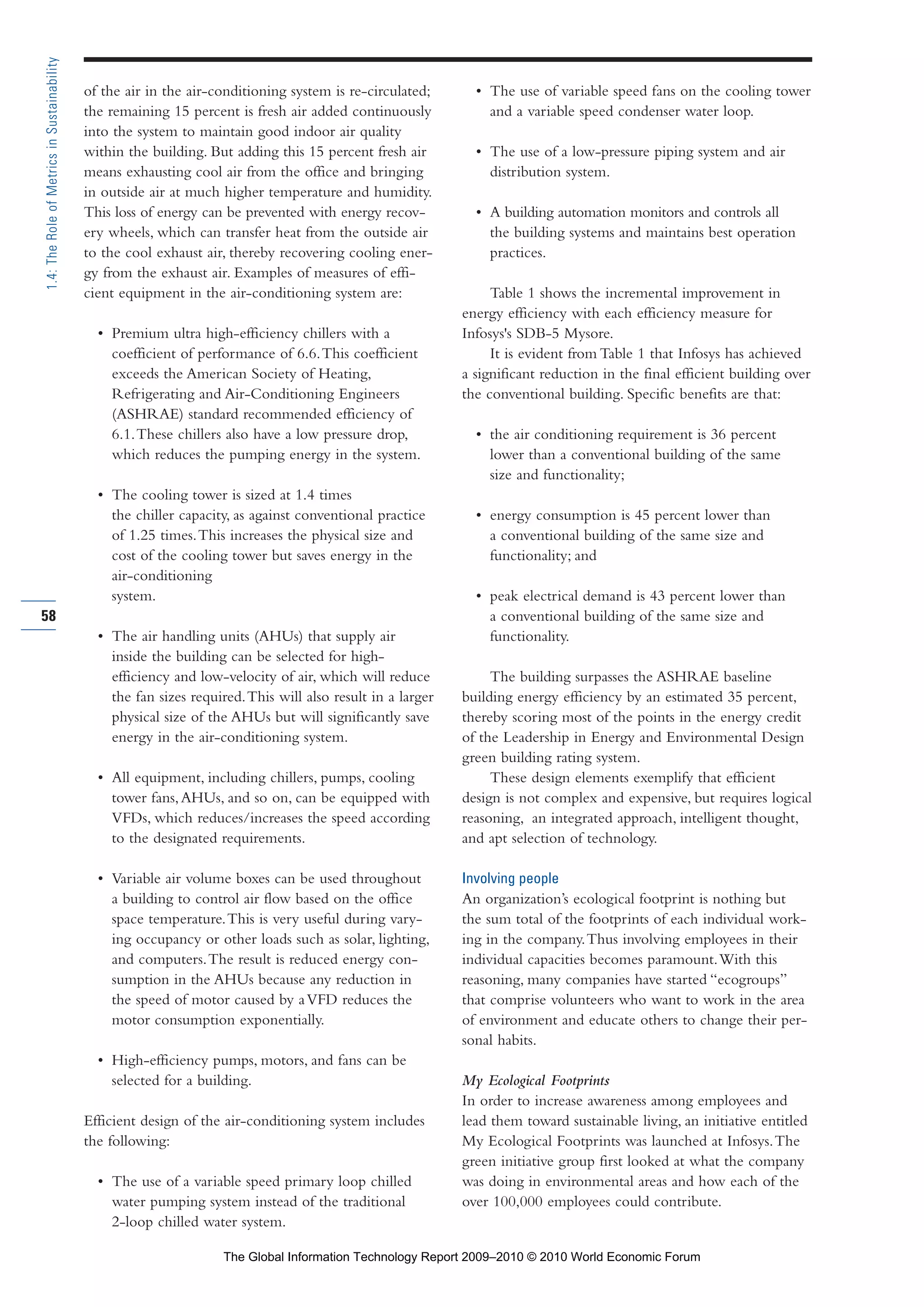

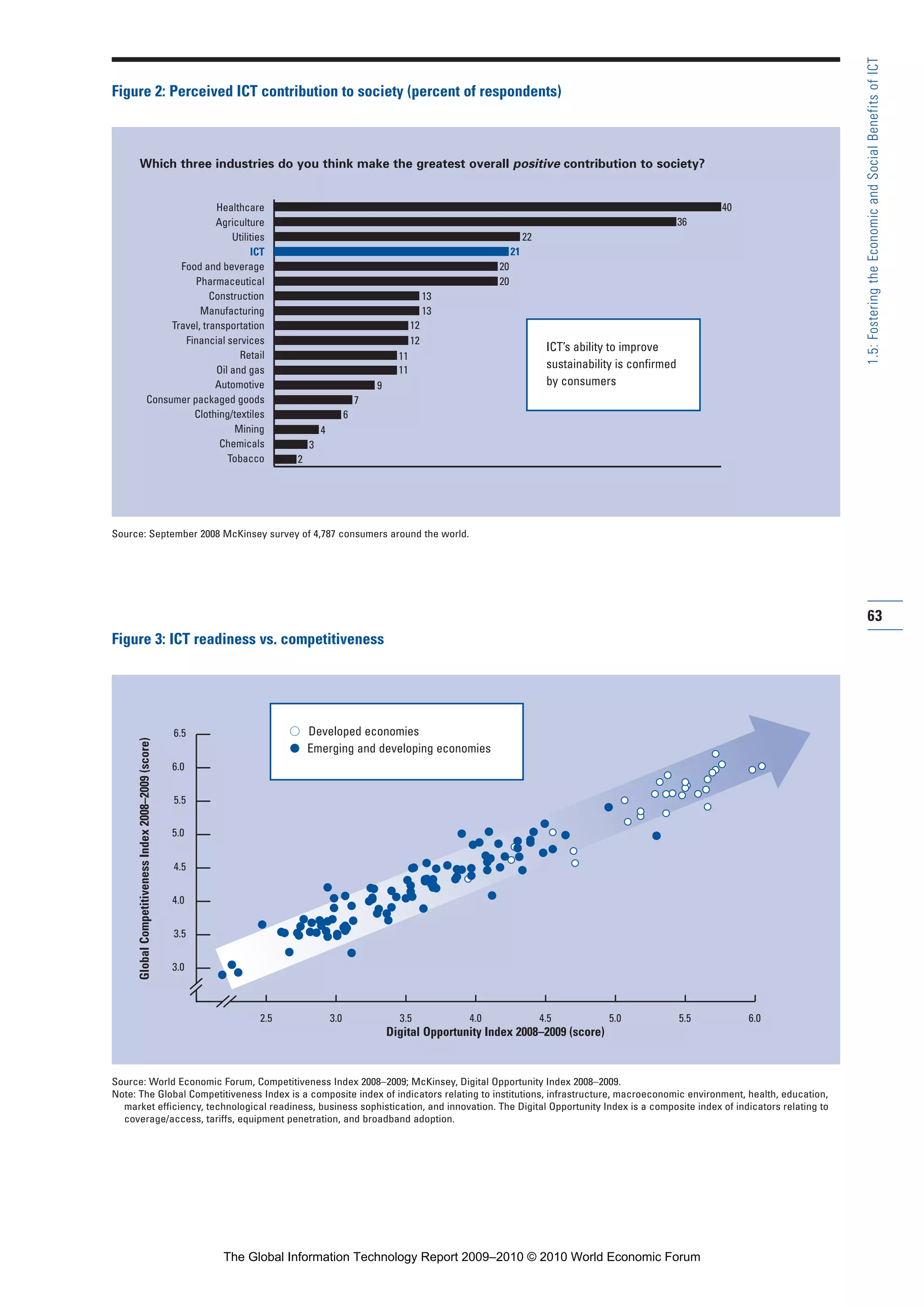

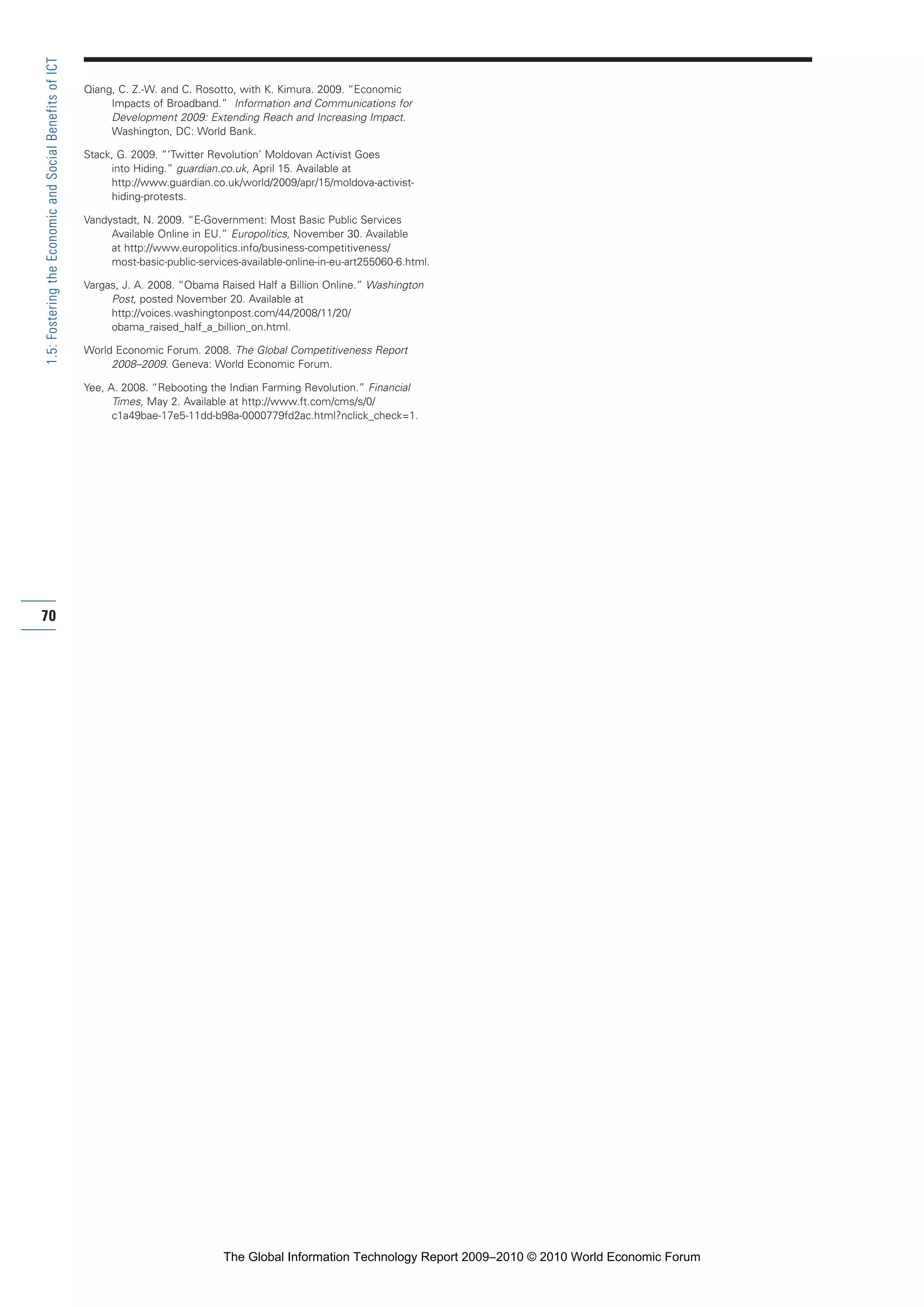

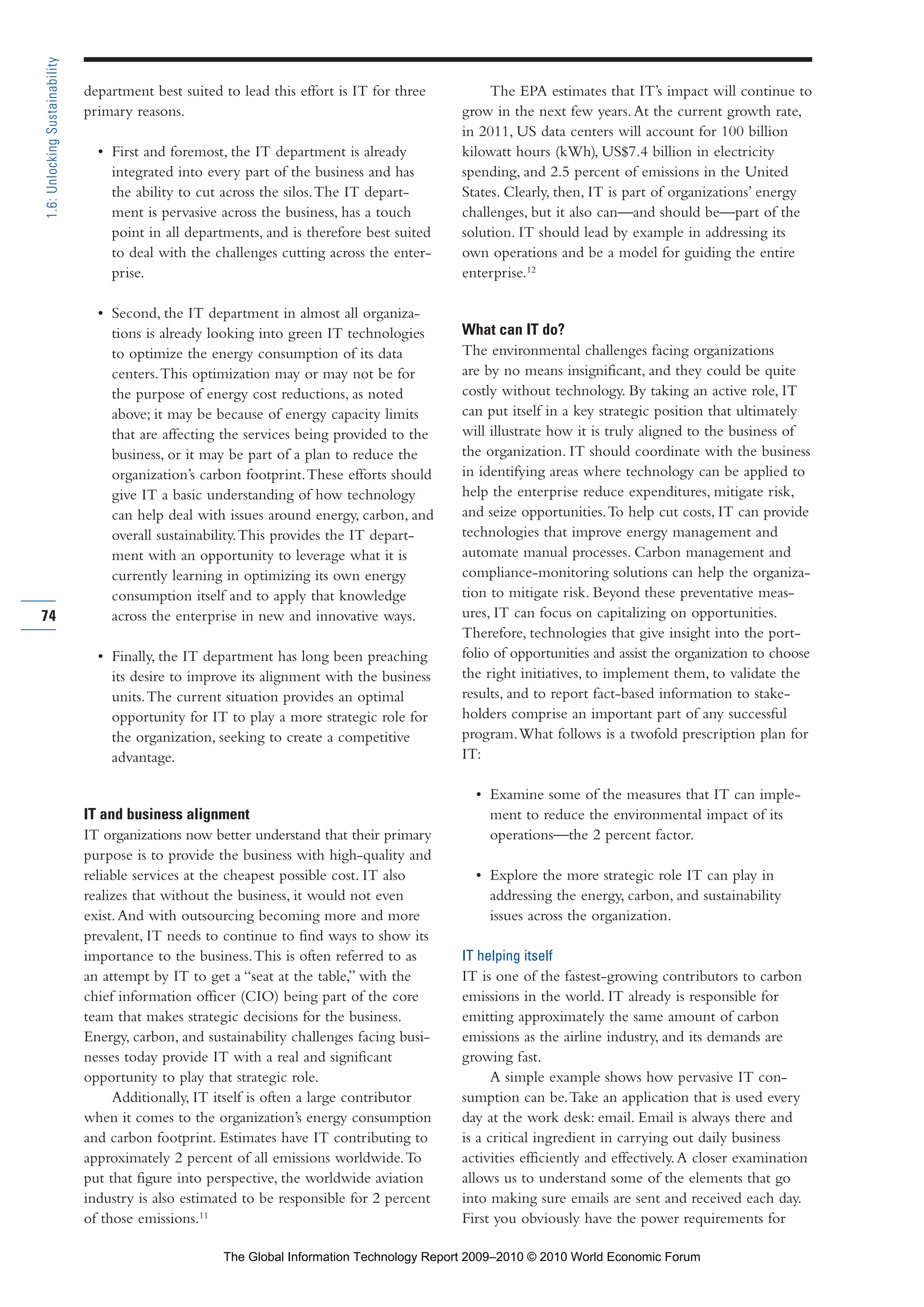

An activity-based approach to carbon management

would show the flow of emissions from assets to a given

department and then further allocated to the different

activities of that department (Figure 6).These assign-

ments are based on a variety of drivers, such as square

footage, airline miles, delivery service efficiency, and so

on. Using this approach, any number of possibilities can

be modeled according to the practical needs of the

organization.

The point is to model to the level of detail required

for management decisions and use the most practical

drivers that represent actual work (and encourage certain

performance), balanced with the level of effort required

to collect the information. If department managers need

to understand their role in the organization’s overall car-

bon reduction goals, then a perfectly exact number is not

necessary.They just need to see their proportion relative

to their peers and how what they do affects the overall

footprint. It is not enough to have just a consumption

figure. Every kilowatt hour of electricity or carload of

coal or gallon of fuel is associated with a business unit

or product line that is unique to the asset using the

energy. One has to understand the broader business

context to be able to look at process optimization and

improvements.

In short, modeling, not calculating, becomes there-

fore the new paradigm for decision making—something

spreadsheets and similar tools have a difficult time

doing.As Bras and Emblemsvåg explain in their book,

Activity-Based Cost and Environmental Management, “. . .

from an ABC [activity-based costing] method’s point of

view, [other natural resources are] simply ‘just another

currency,’ and the principles remain unchanged.”13

In the simplest terms, by replacing the “currency”

of cost with other resources, we can gain the same kinds

of insights about emissions, water, waste, or energy that

have proven so invaluable in the cost-accounting world.

Combine those resources with cost, and as one begins

to model change, one will also see the financial impact

of one’s decisions, making it easier to prioritize and cost

justify recommendations.

89

1.7:TheEvolvingScienceofManagingforSustainability

Figure 6: Example of a model of greenhouse gas values: Carbon footprint modeling methodology

∞

Facility

Scope

Geography

Activities that drive or otherwise

consume emissions

Activity module

∞

Equipment

Activity

Organization

Products and services delivered

to customers

Cost object module

∞

Customer

Channel

Product

Raw sources of

greenhouse gas and

CO2 equivalents

Contains inventory

and rates

Sources of CO2

• Electricity

• Jet fuel

• Natural gas

• Bio-fuels

• Refrigerants

Calculated CO2 of raw

materials from other

upstream suppliers

External

units module

Time

Scenario

Note: In this example, greenhouse gas values are derived from electricity consumption figures, then assigned to buildings/equipment and modeled just as in a

traditional ABM model.

Part 1.r2 3/2/10 4:40 AM Page 89

The Global Information Technology Report 2009–2010 © 2010 World Economic Forum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cusersdesktop2010gitr2009-2010fullreportfinal-100402152331-phpapp01/75/The-Global-Information-Technology-Report-2009-2010-109-2048.jpg)

![CHAPTER 1.9

The Economic Consequences

of the Diffusion of Cloud

Computing

FEDERICO ETRO, University of Milano-Bicocca and Intertic

Cloud computing is an emerging general purpose tech-

nology (GPT) that could provide a fundamental contri-

bution to efficiency in the private and public sectors,

as well as promote growth, competition, and business

creation. It is an Internet-based technology through

which information is stored in servers and provided as

an on-demand service to clients.The impact of cloud

computing on both households and companies will be

substantial. On one side, consumers will be able to

access all of their documents and data from any device

(the home or work personal computer [PC], the

mobile phone, or an Internet point, among others) as

they already can for email services or social networks.

On the other side, firms will be able to rent computing

power (both hardware and software in their latest ver-

sions) and storage from a service provider and pay on

demand, as they already do for other inputs such as

energy and electricity.1

The former application will

affect our lifestyles, but the latter will have a profound

impact on the cost structure of all the industries using

hardware and software,2

and therefore it will have an

indirect but crucial impact on business creation and on

the macroeconomic performance of countries.

Cloud computing can exert a number of effects

on the economy. For instance, it can enable huge cost

savings and more efficiency in large areas of the public

sector, including hospitals and healthcare (especially for

providing information and technology to remote or

poorer locations), education (especially for e-learning),

and the activities of government agencies that experi-

ence periodic peaks in usage. Moreover, substantial posi-

tive externalities are expected because of energy savings:

the improvement of energy efficiency may contribute to

the reduction of total carbon emissions in a substantial

way—information and communication technologies

(ICT) is responsible for 2 percent of carbon emissions

in Europe, of which 1.75 percent is due to the use of

ICT products and services, and 0.25 percent to their

production.The introduction of cloud computing can

provide cost savings in the private sector as well: it can

create multilateral network effects among businesses

and increase productivity within businesses, and it can

promote entry and innovation in all the sectors where

ICT costs are relevant and are drastically reduced by

the adoption of cloud computing.This last effect can

be quite large in terms of consequences for the aggre-

gate economy, and is the focus of the evaluation of the

economic impact of cloud computing on the economy

conducted in this chapter.

In a recent study, we estimated the economic

impact of the diffusion of cloud computing in Europe

through incentives to new business creation.3

Starting

from conservative assumptions about the cost-reduction

process associated with the spread of cloud computing

over five years, we obtained results showing that the

diffusion of cloud computing could provide a positive

and substantial contribution to the annual growth rate

107

1.9:TheEconomicConsequencesoftheDiffusionofCloudComputing

Part 1.r2 3/2/10 4:40 AM Page 107

The Global Information Technology Report 2009–2010 © 2010 World Economic Forum](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cusersdesktop2010gitr2009-2010fullreportfinal-100402152331-phpapp01/75/The-Global-Information-Technology-Report-2009-2010-127-2048.jpg)