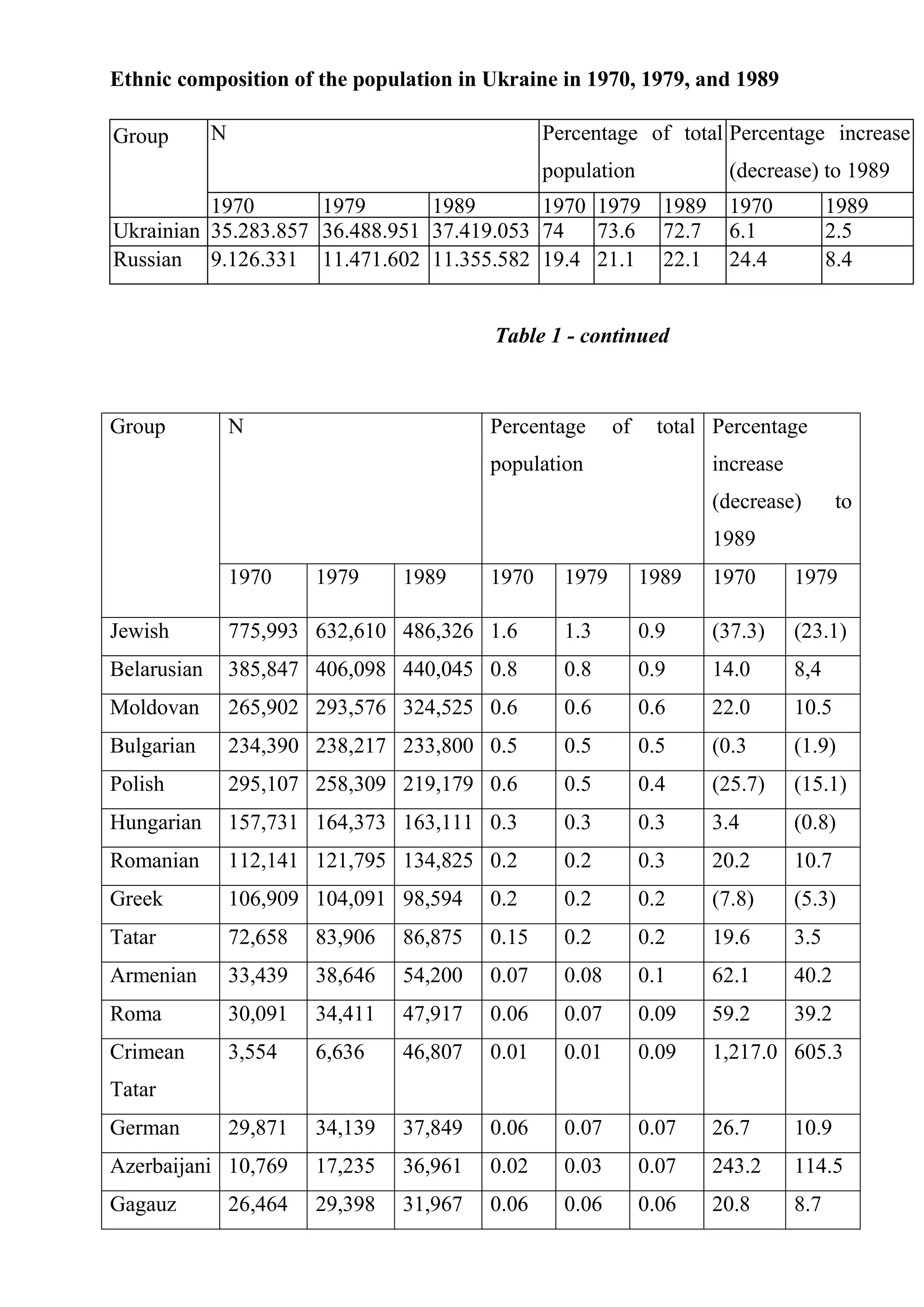

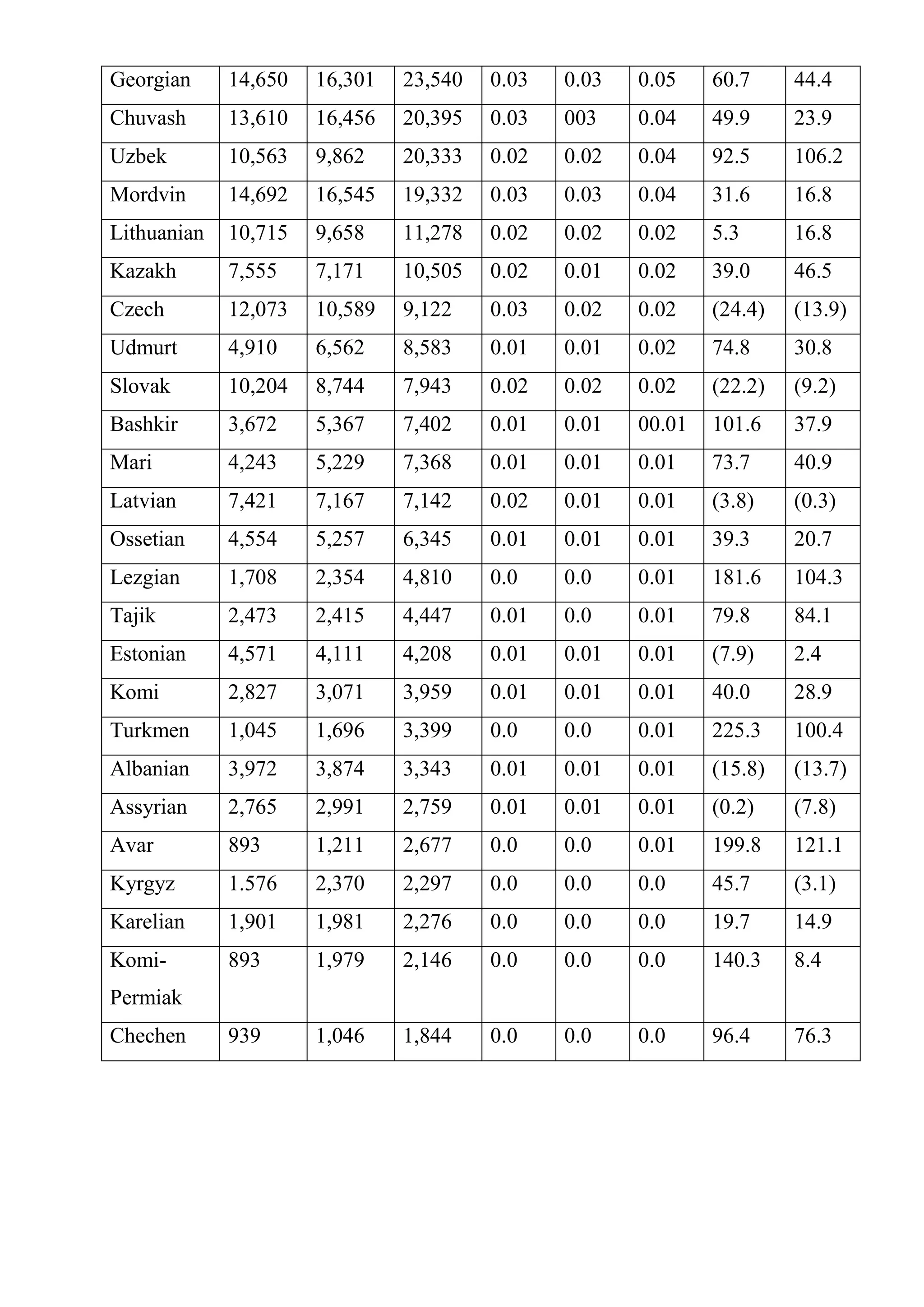

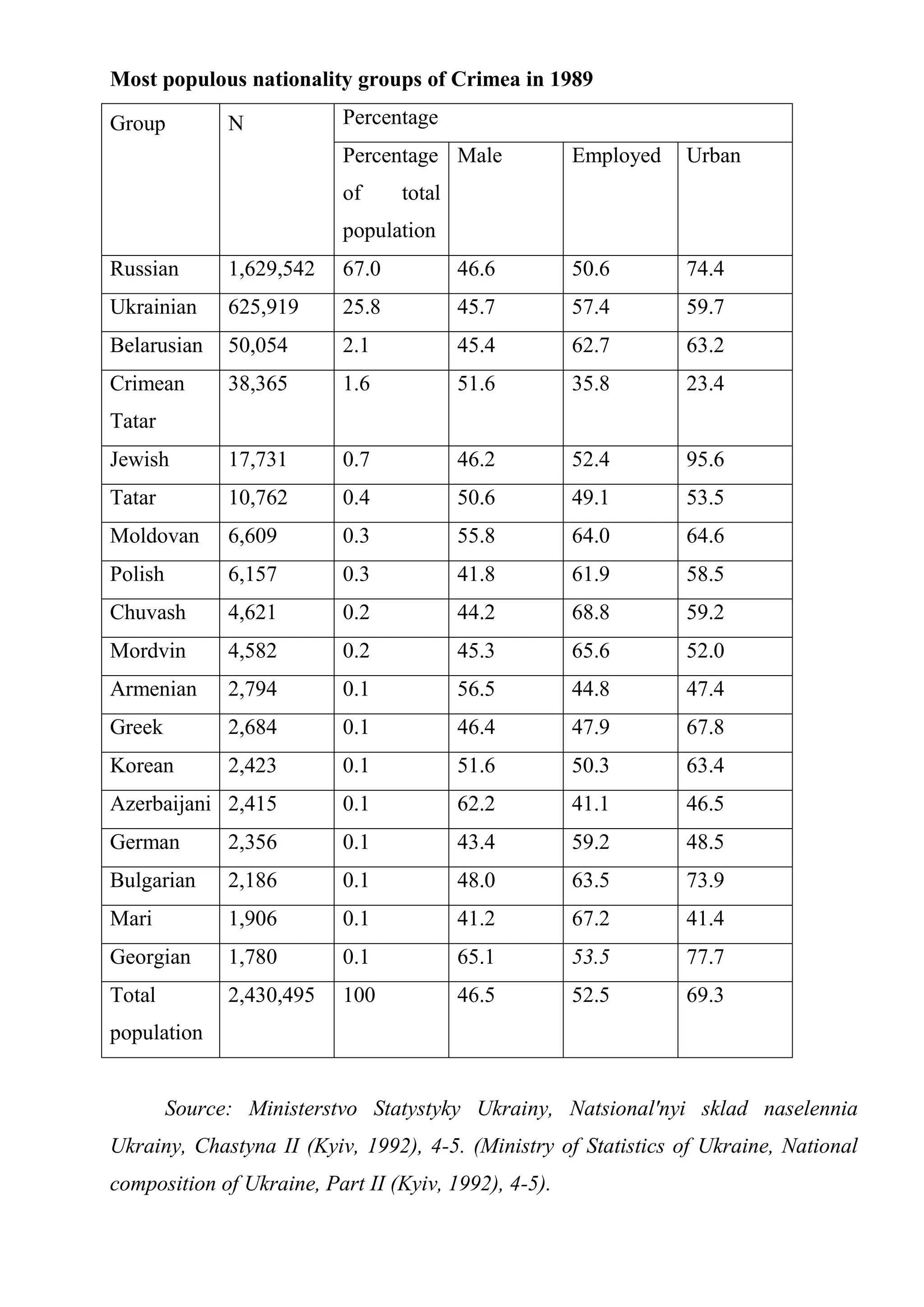

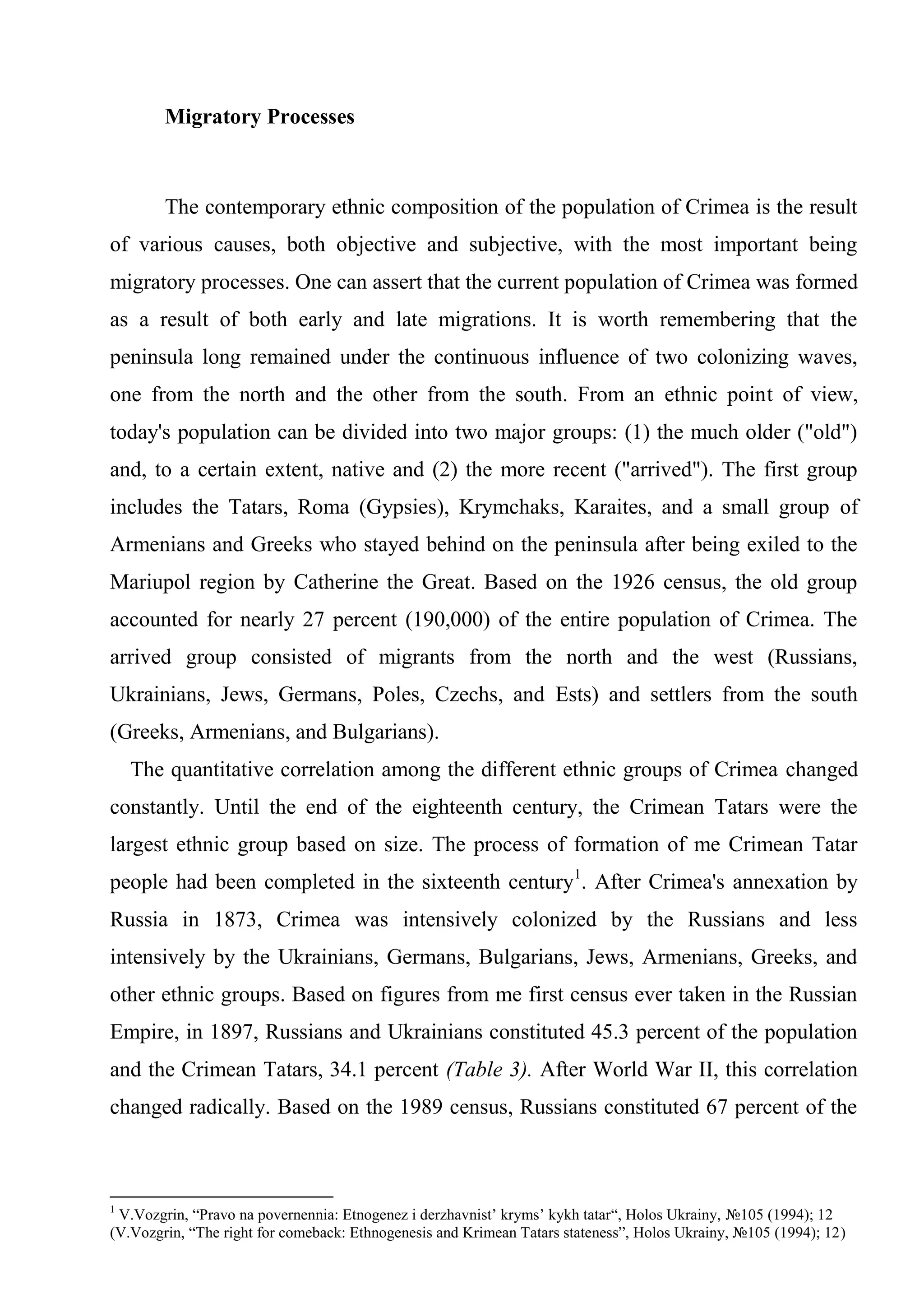

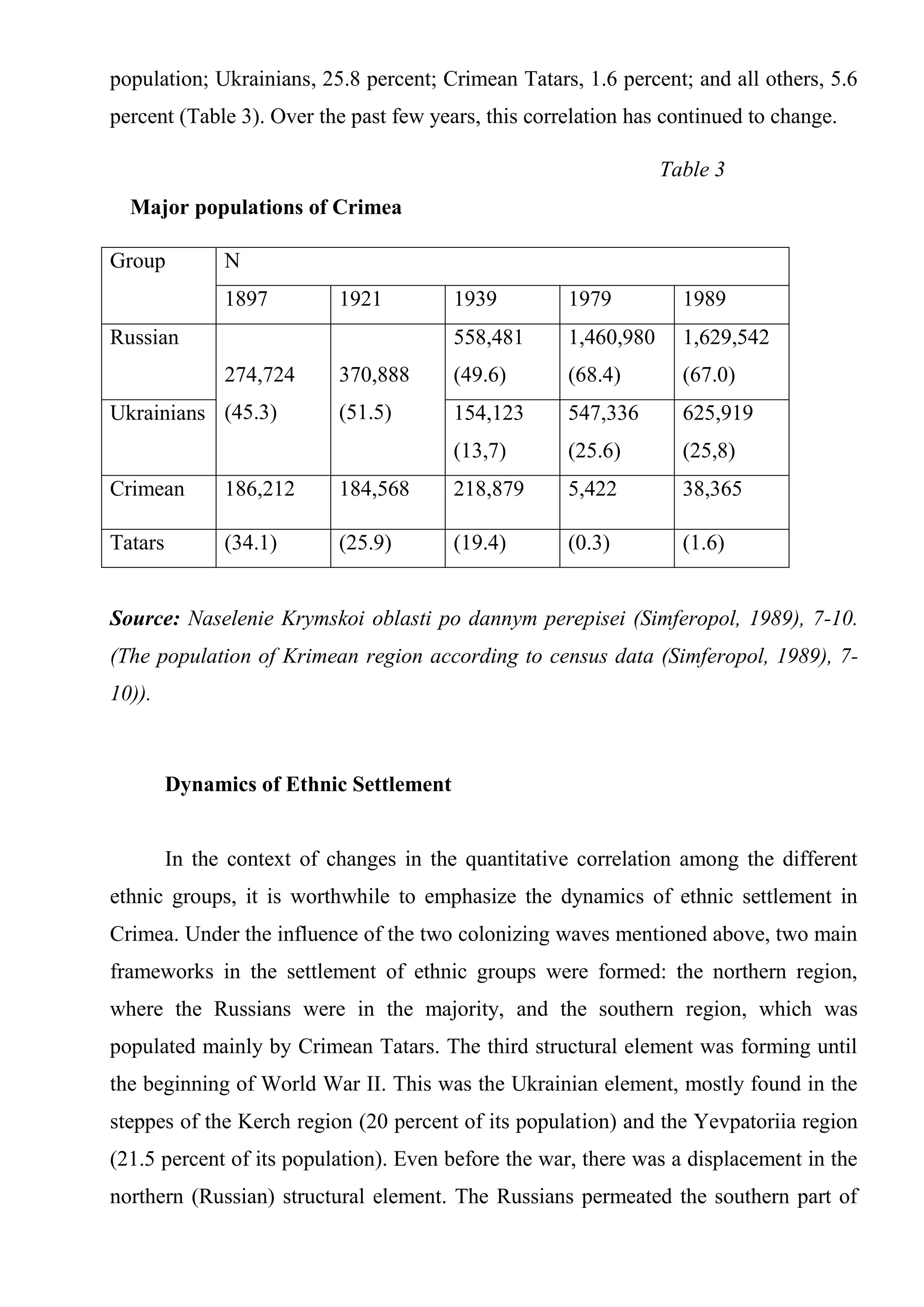

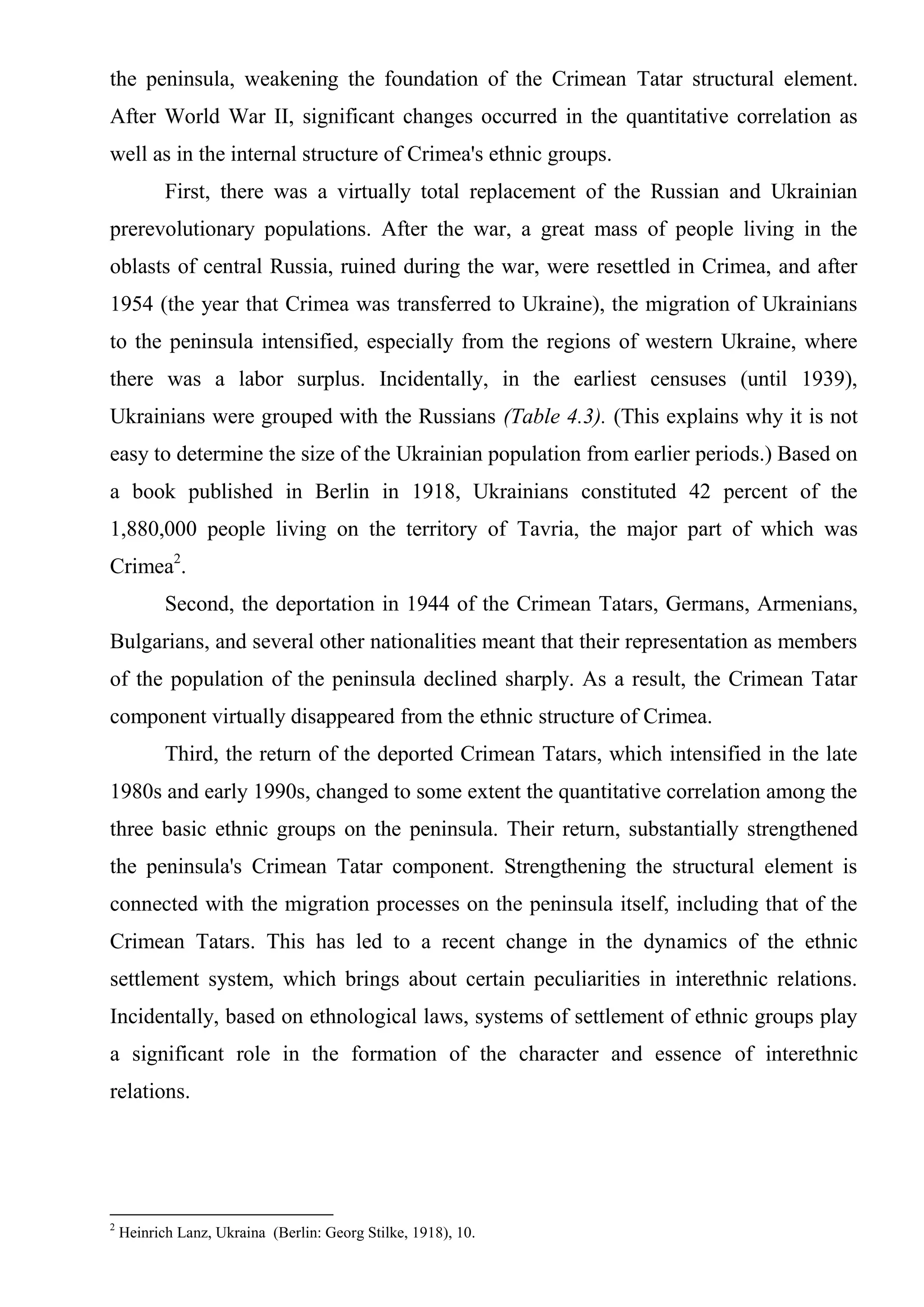

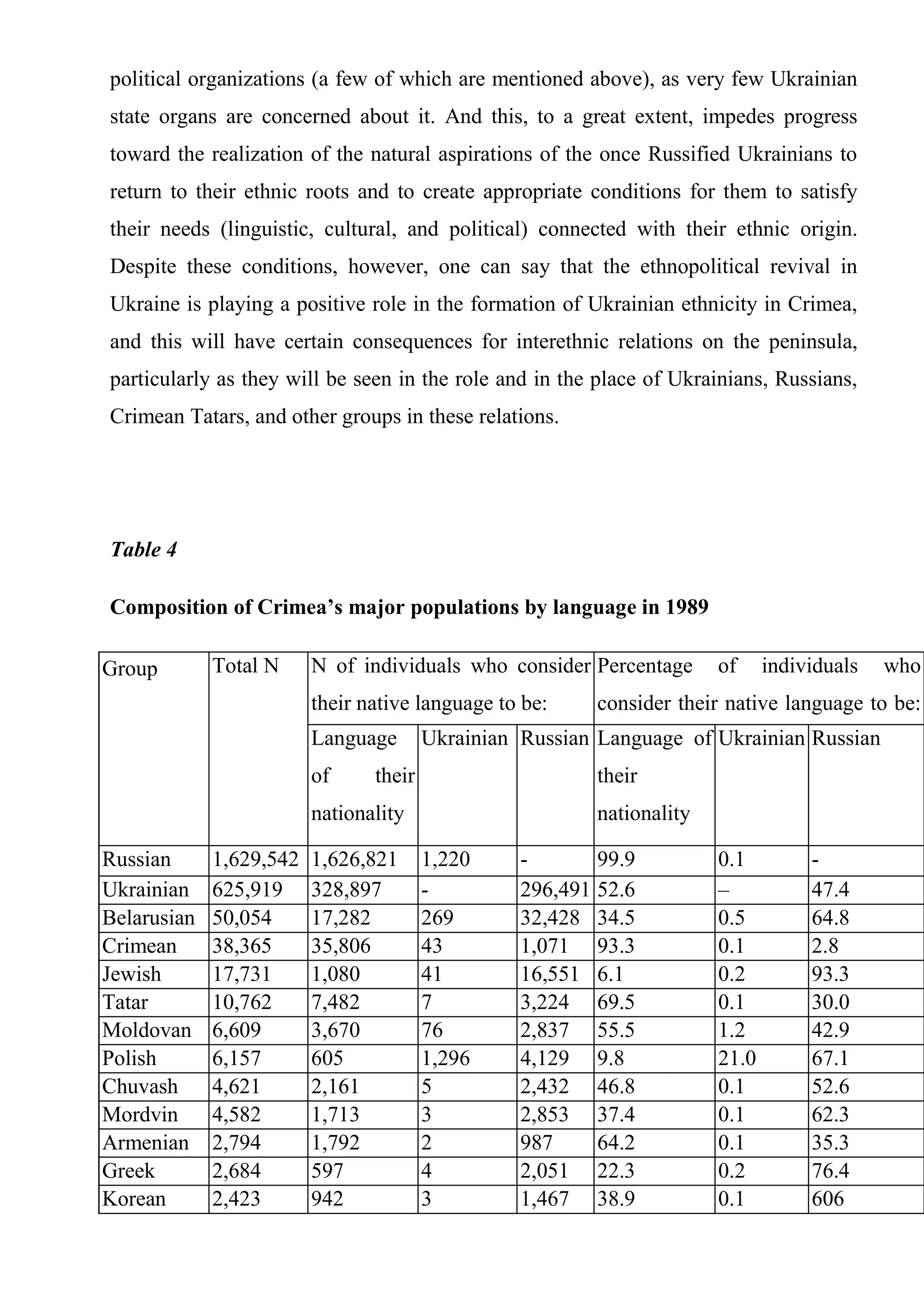

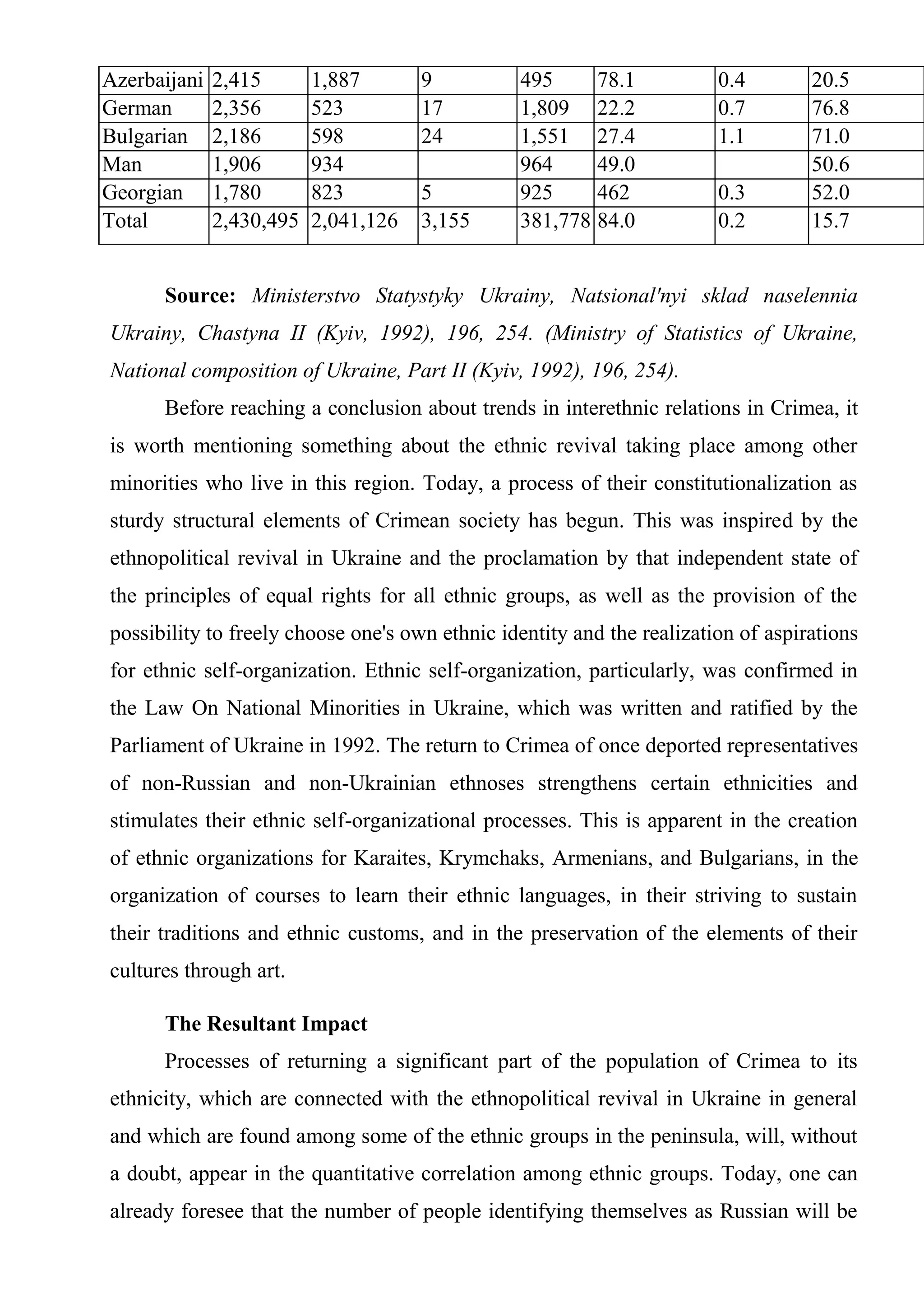

This document analyzes the dynamics of interethnic relations in Crimea. It discusses the ethnic diversity of Crimea, which has over 100 ethnic groups and the six most populous being Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Crimean Tatars, Jews, and Tatars. It provides data on the population sizes of various ethnic groups from censuses between 1970-1989, showing increases and decreases. Key factors that determine contemporary interethnic relations in Crimea are the historical formation of the population's ethnic composition, dynamics of ethnic settlement patterns, current migration trends, ethnic group constitutionalization, and interactions between the largest ethnic groups.