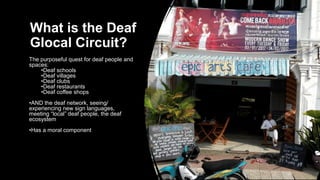

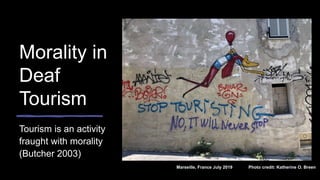

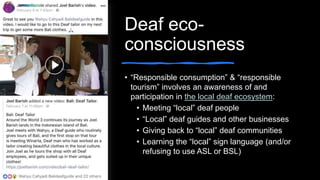

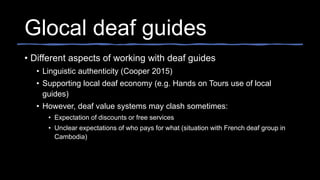

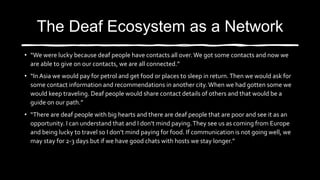

The document discusses the concept of the "Deaf Glocal Circuit," which refers to deaf people purposefully traveling to experience deaf spaces and communities around the world. It explores how sign languages and deaf spaces have become commodified for deaf tourism. While this tourism can support local deaf economies, it also raises issues of authenticity and responsibility. The document examines theories around tourist encounters and the morality of exchange, arguing that deaf tourism involves complex political, cultural, and moral dimensions beyond just economic exchange.