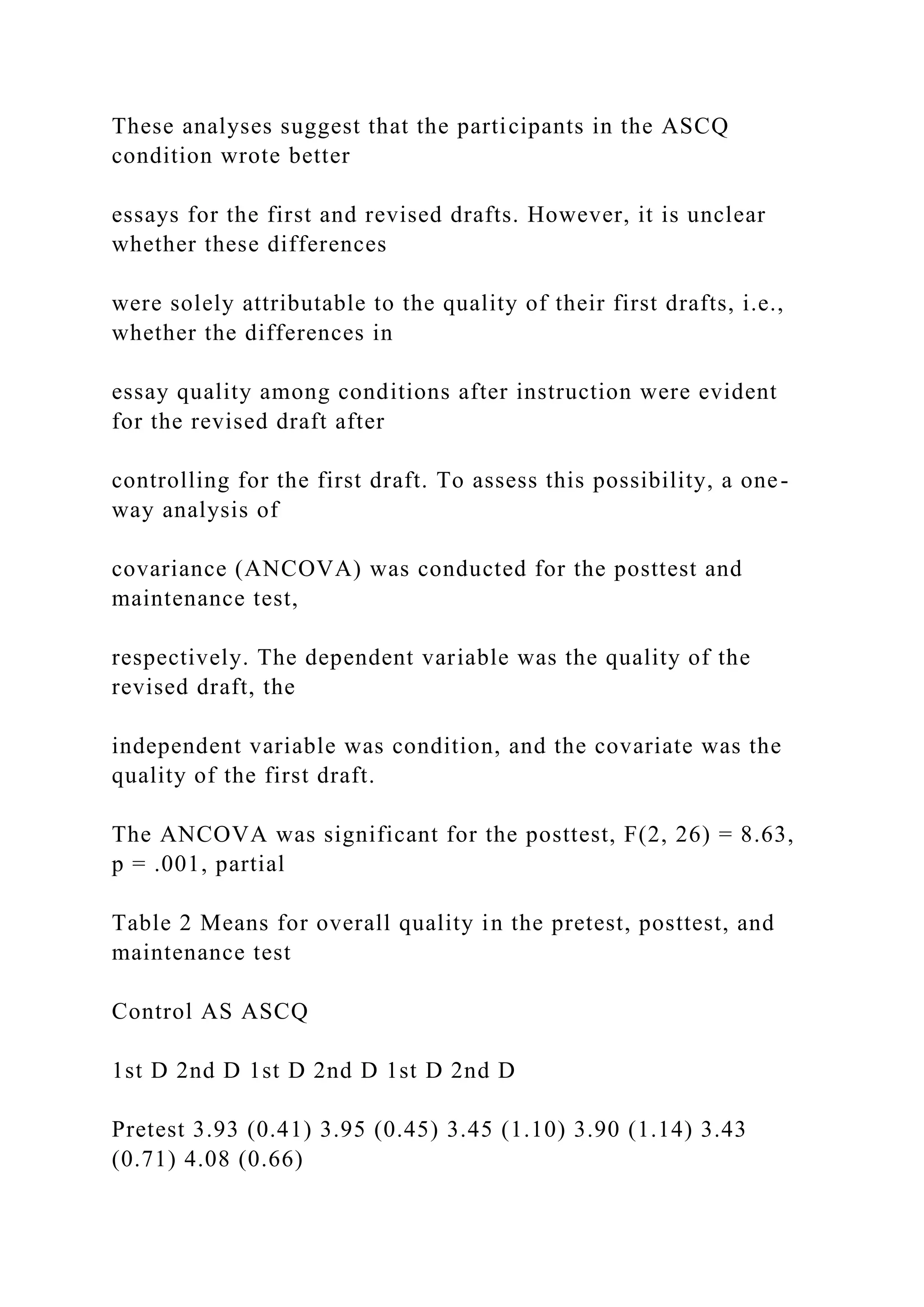

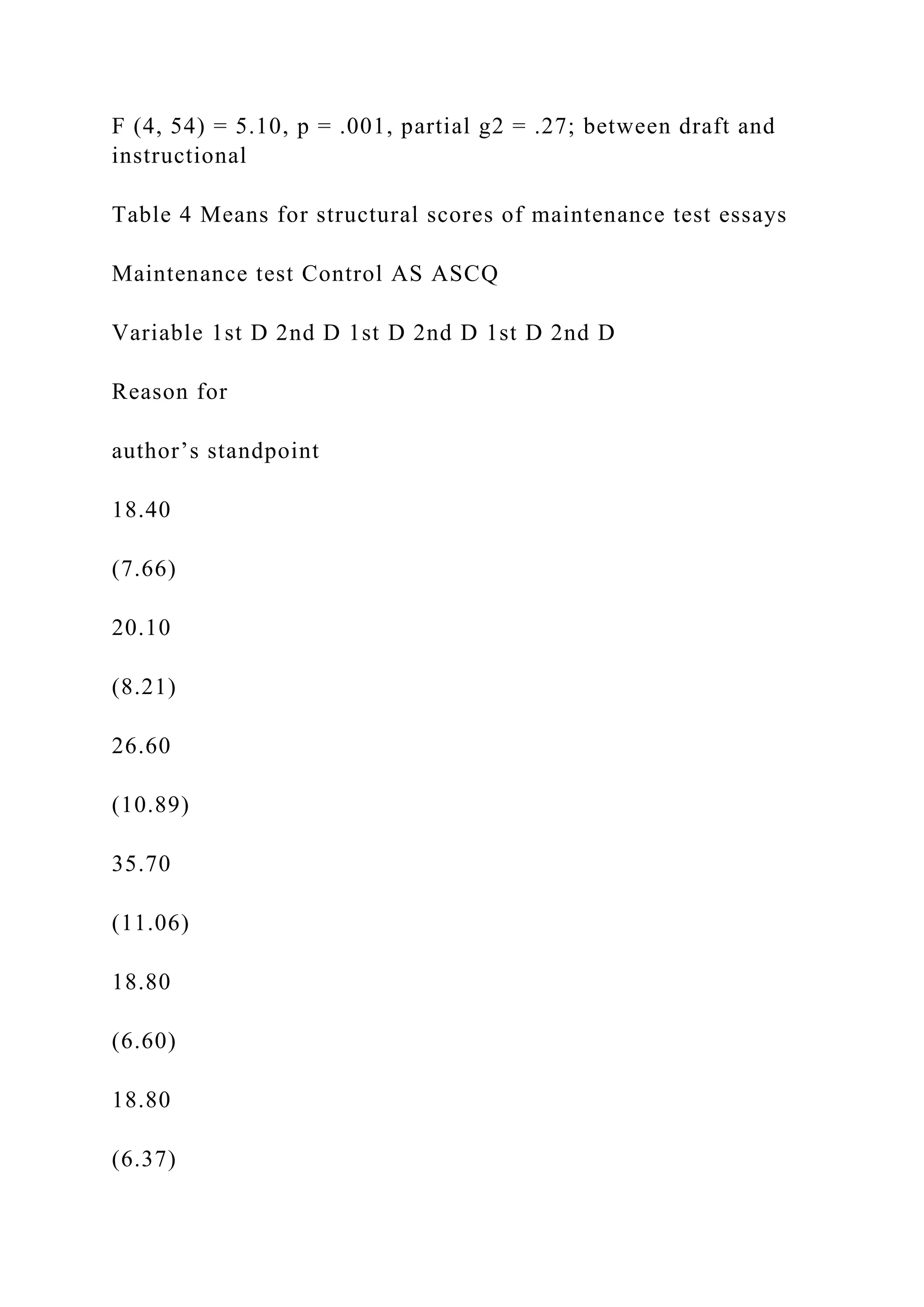

This study examines the impact of self-regulated strategy development (SRSD) instruction on college students' argumentative essays, specifically focusing on teaching critical questions and argumentation schemes. Students who learned to ask and answer critical questions while revising produced higher quality essays with more counterarguments and alternative viewpoints. The research suggests that incorporating critical questioning into writing instruction enhances students' argumentative sensitivity and overall essay quality.

![about either the argumentation schemes or the critical questions.

Compared to

students in the contrasting conditions, those who were taught to

ask and answer

critical questions wrote essays that were of higher quality, and

included more

counterarguments, alternative standpoints, and rebuttals. These

findings indicate

that strategy instruction that includes critical standards for

argumentation increases

college students’ sensitivity to alternative perspectives.

Keywords Argumentation schemes � Critical questions �

Strategy instruction �

Argumentative writing � Revision

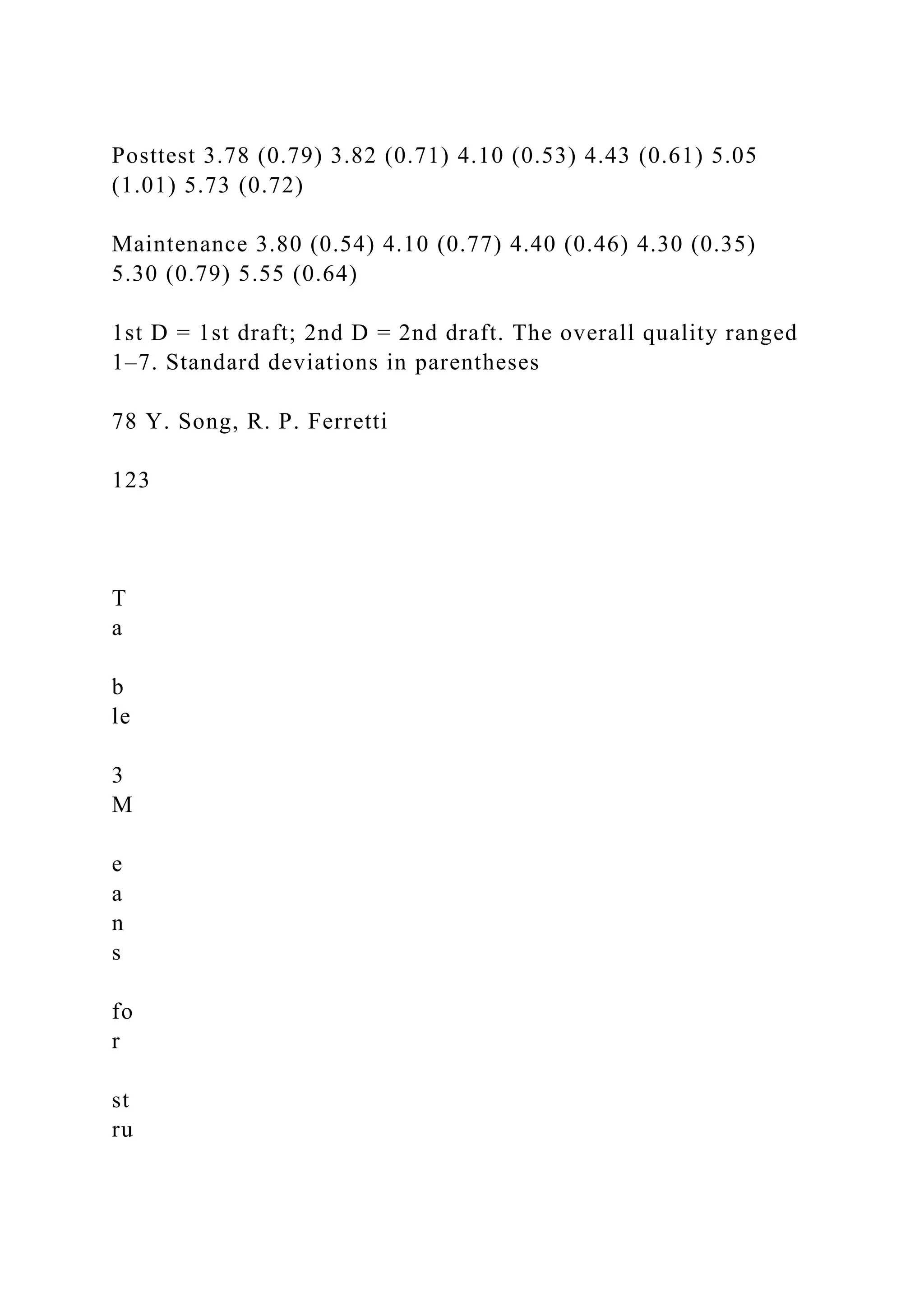

Introduction

Communication about controversial issues presumes the

capacity to consider

potentially relevant evidence, entertain alternative perspectives,

and arrive at a

Y. Song (&)

School of Education, University of Delaware, Newark, DE

19716, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

R. P. Ferretti](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/teachingcriticalquestionsaboutargumentationthroughther-221026123424-5bfe3b98/75/Teaching-critical-questions-about-argumentationthrough-the-r-docx-2-2048.jpg)

![School of Education, University of Delaware, 015 C Willard

Hall, Newark, DE 19716, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

123

Read Writ (2013) 26:67–90

DOI 10.1007/s11145-012-9381-8

reasonable standpoint based on an evaluation of the justificatory

strategies used to

accomplish their discursive purposes (van Eemeren &

Grootendorst, 2004; van

Eemeren, Grootendorst, & Henkemans, 1996; Walton, Reed, &

Macagno, 2008).

Unfortunately, the evidence shows that people often ignore

relevant information

that is inconsistent with their perspective, i.e., my-side bias

(Perkins, Farady, &

Bushey, 1991), do not consider potential counterarguments

(Kuhn, 1991), lack

standards for evaluating argumentative strategies (Ferretti,

Lewis, & Andrews-

Weckerly, 2009; Nussbaum & Edwards, 2011), and fail to adapt

their strategies to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/teachingcriticalquestionsaboutargumentationthroughther-221026123424-5bfe3b98/75/Teaching-critical-questions-about-argumentationthrough-the-r-docx-3-2048.jpg)