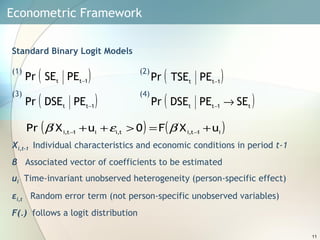

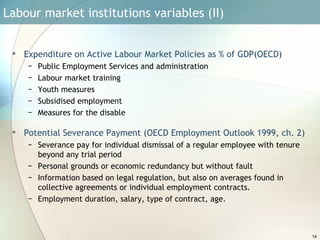

The document discusses dependent self-employment as a way for employers to evade strict employment protection legislation. It analyzes data from the European Community Household Panel from 1994-2001 to examine transitions from paid employment to dependent or true self-employment. The results show that stricter employment protection legislation and active labor market policies increase transitions to dependent self-employment, while the business cycle and potential severance payments also influence the likelihood of different transition types. The conclusions question whether policies encouraging self-employment are well-designed and whether measures should be taken to address dependent self-employment.

![Results (III) EXERCISE (1) EXERCISE (2) EXERCISE (3) EXERCISE (4) Prob [SE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [TSE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [DSE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [DSE t (vs. TSE t )] Variables Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Incomes Dwelling owner 1.93% 0.3 -7.73% -0.89 16.05% 1.68* 12.21% 1.62* Capital & property incomes (1 lag)(x e-3) 2.71% 3.58*** 1.92% 1.58 3.07% 3.23*** 2.15% 1.62* Work incomes (x e-2) 0.1% 0.29 0.33% 0.74 0.01% 0.01 -0.53% -0.88 Business cycle Unemployment rate 1.33% 0.8 -4.42% -1.82* 7.63% 3.12*** 6.75% 3.13*** Country Austria (5) -31.54% -1.74* -41.11% -1.84* -33.44% -1.16 20.6% 0.66 Belgium (5) -52.81% -4.72*** -37.28% -2.04** -79.21% -5.75*** -38.18% -1.7* Denmark (5) -16.48% -0.87 -24.61% -1.05 -11.12% -0.35 12.46% 0.44 Finland (5) 27.34% 1.61 -1.02% -0.05 67.53% 2.2** 38.18% 2.47*** Germany (5) -56.4% -5.08*** -43.68% -2.45*** -78.92% -5.26*** -19.79% -0.99 Italy (5) 63.65% 3.45*** 27.6% 1.22 127.22% 3.54*** 44.95% 3.37*** Netherlands (5) -44.98% -2.96*** -69.32% -3.52*** 1.45% 0.04 59.54% 2.41** Portugal (5) 24.95% 1.09 3.55% 0.13 70.22% 1.61 41.57% 1.81* United Kingdom (5) -36.95% -2.69*** -3.9% -0.16 -115.3% -9.47*** -85.31% -6.88*** Reference categories : (5) Spain Log likelihood -7442.81 -4798.64 -3446.73 -815.72](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tarea-091211045816-phpapp02/85/Tarea-12-320.jpg)

![Results (IV) EXERCISE (1) EXERCISE (2) EXERCISE (3) EXERCISE (4) Prob [SE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [TSE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [DSE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [DSE t (vs. TSE t )] # observations 157016 156293 156195 1544 # transitions 1544 821 723 723 vs. 821 Predicted probability 0.00463 0.00257 0.00129 0.45965 Variables Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Business cycle Unemployment rate -0.36% -0.43 -4.43% -3.09*** 6.11% 4.9*** 5.32% 3.99*** Labour Market Institutions EPL index for regular employment 0.86% 0.26 -8.09% -1.79* 32.56% 5.55*** 21.48% 4.17*** EPL index for temporary employment 11.94% 4.52*** 6.95% 1.75* 26.21% 6.78*** 10.57% 3.01*** Social Security Laws index 573.93% 9.06*** 362.46% 3.42*** 973.91% 9.18*** 344.93% 3.49*** Expenditure on ALMP as % of GDP -7.67% -1 -32.15% -2.9*** 74.04% 4.97*** 57.28% 4.45*** Log likelihood -7472.76 -4810.06 -3486.88 -832.45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tarea-091211045816-phpapp02/85/Tarea-15-320.jpg)

![Results (V) EXERCISE (1) EXERCISE (2) EXERCISE (3) EXERCISE (4) Prob [SE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [TSE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [DSE t | PE t-1 ] Prob [DSE t (vs. TSE t )] # observations 157016 156293 156195 1544 # transitions 1544 821 723 723 vs. 821 Predicted probability 0.00462 0.00261 0.00140 0.46854 Variables Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Marg. eff. t-stat. Business cycle Unemployment rate -0.44% -0.56 -4.01% -3.02*** 4.12% 3.41*** 3.89% 3.35*** Labour Market Institutions EPL index for temporary employment 12.53% 4.81*** 7.27% 1.88* 24.01% 6.34*** 9.25% 2.57*** Social Security Laws index 574.59% 9.08*** 370.47% 3.47*** 888.7% 8.57*** 326.70% 3.36*** Expenditure on ALMP as % of GDP -8.49% -1.15 -30.56% -2.81*** 35.4% 2.82*** 40.03% 3.64*** Potential severance payment (x e-3) -0.21% -0.64 -1.99% -2.85*** 0.89% 2.83*** 1.68% 3.36*** Log likelihood -7472.58 -4804.81 -3498.80 -838.04](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tarea-091211045816-phpapp02/85/Tarea-16-320.jpg)