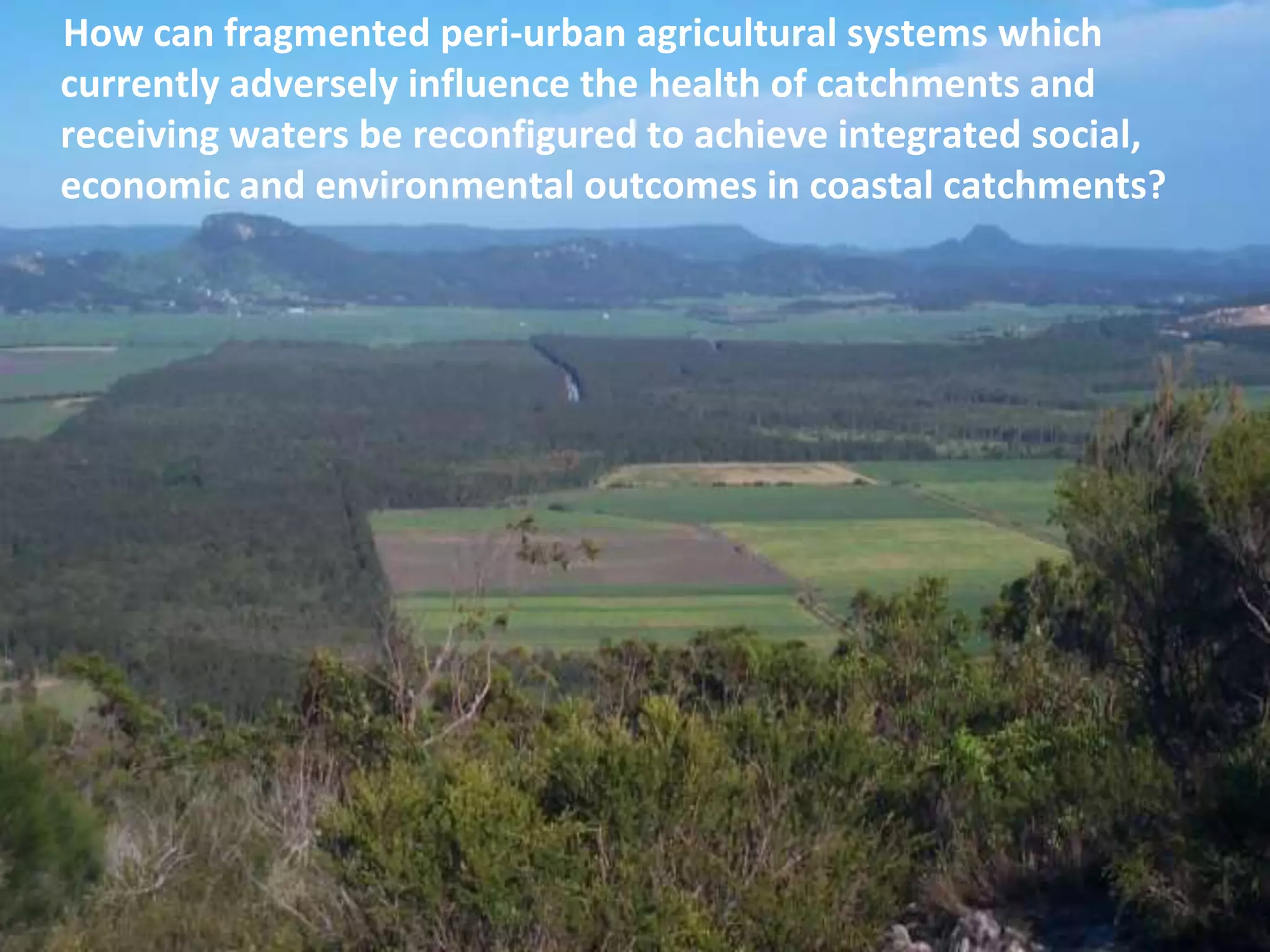

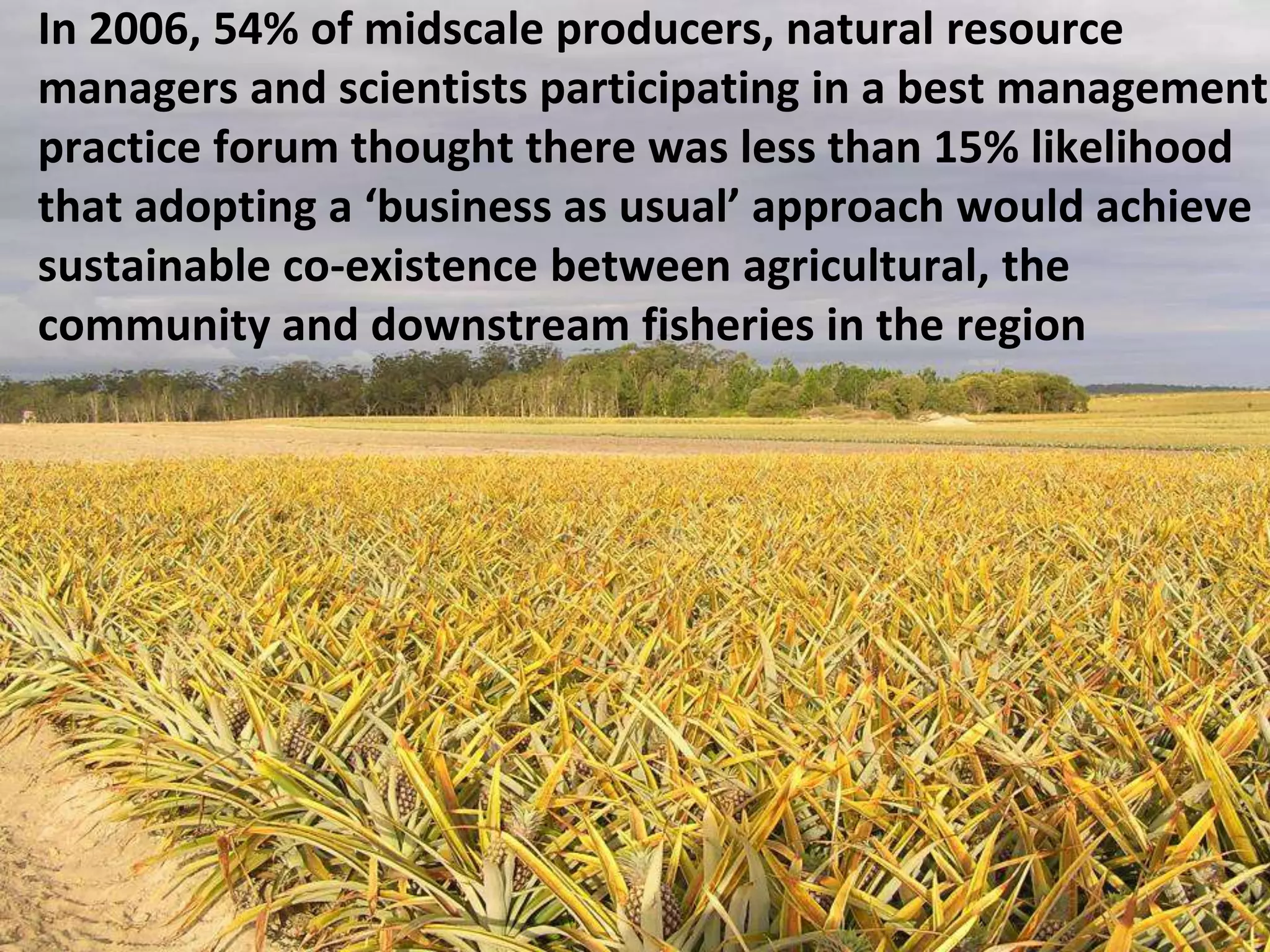

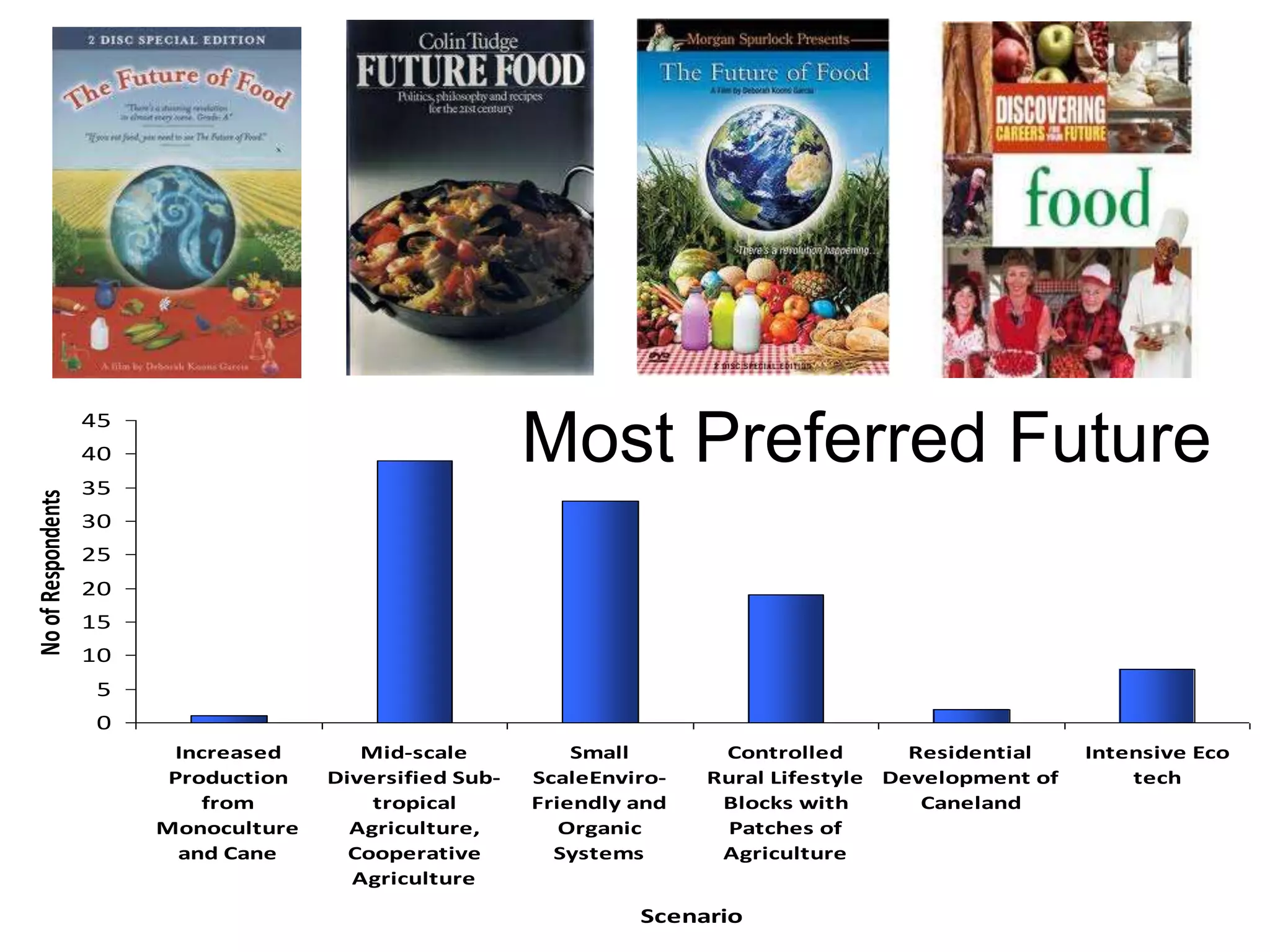

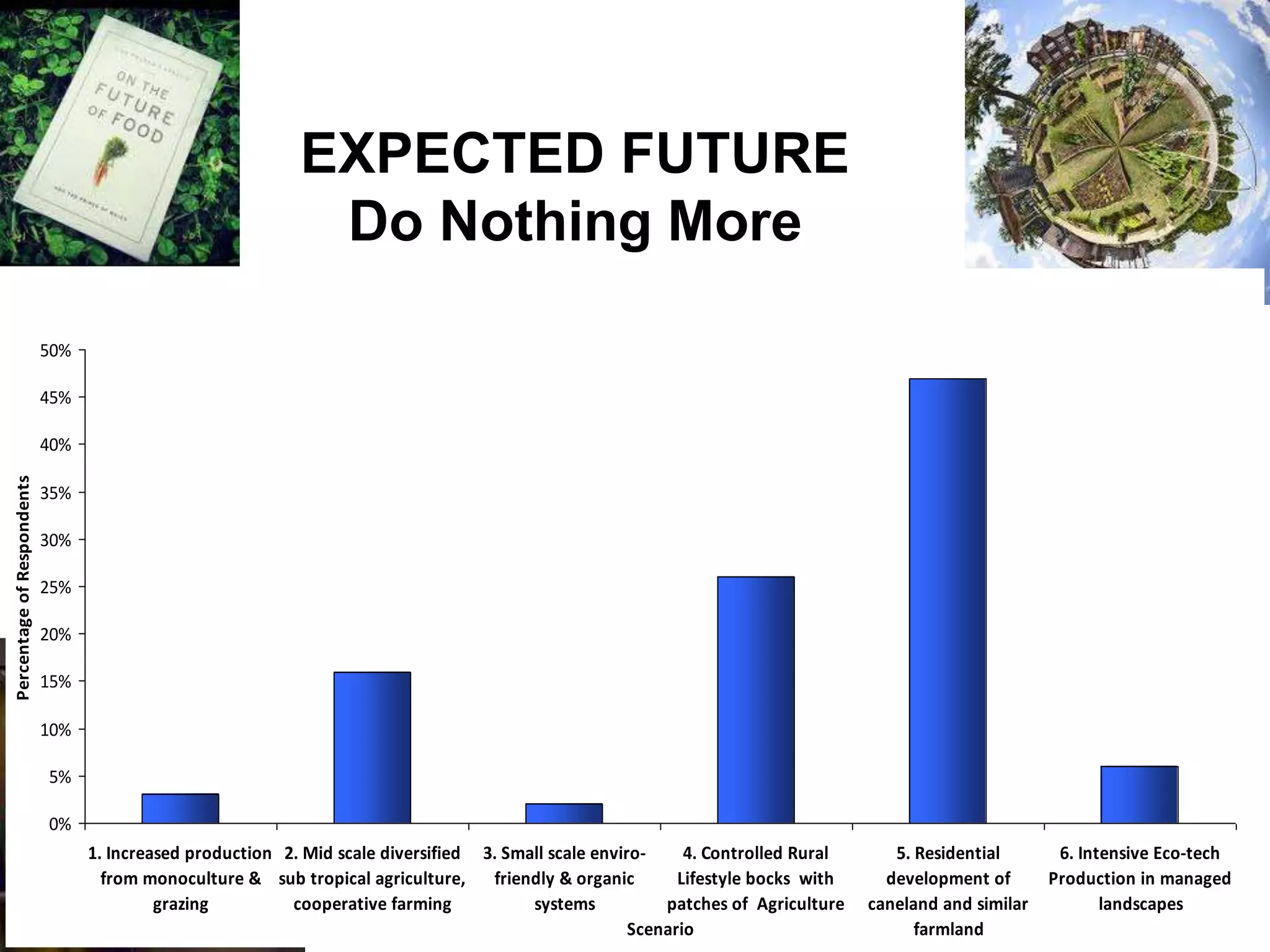

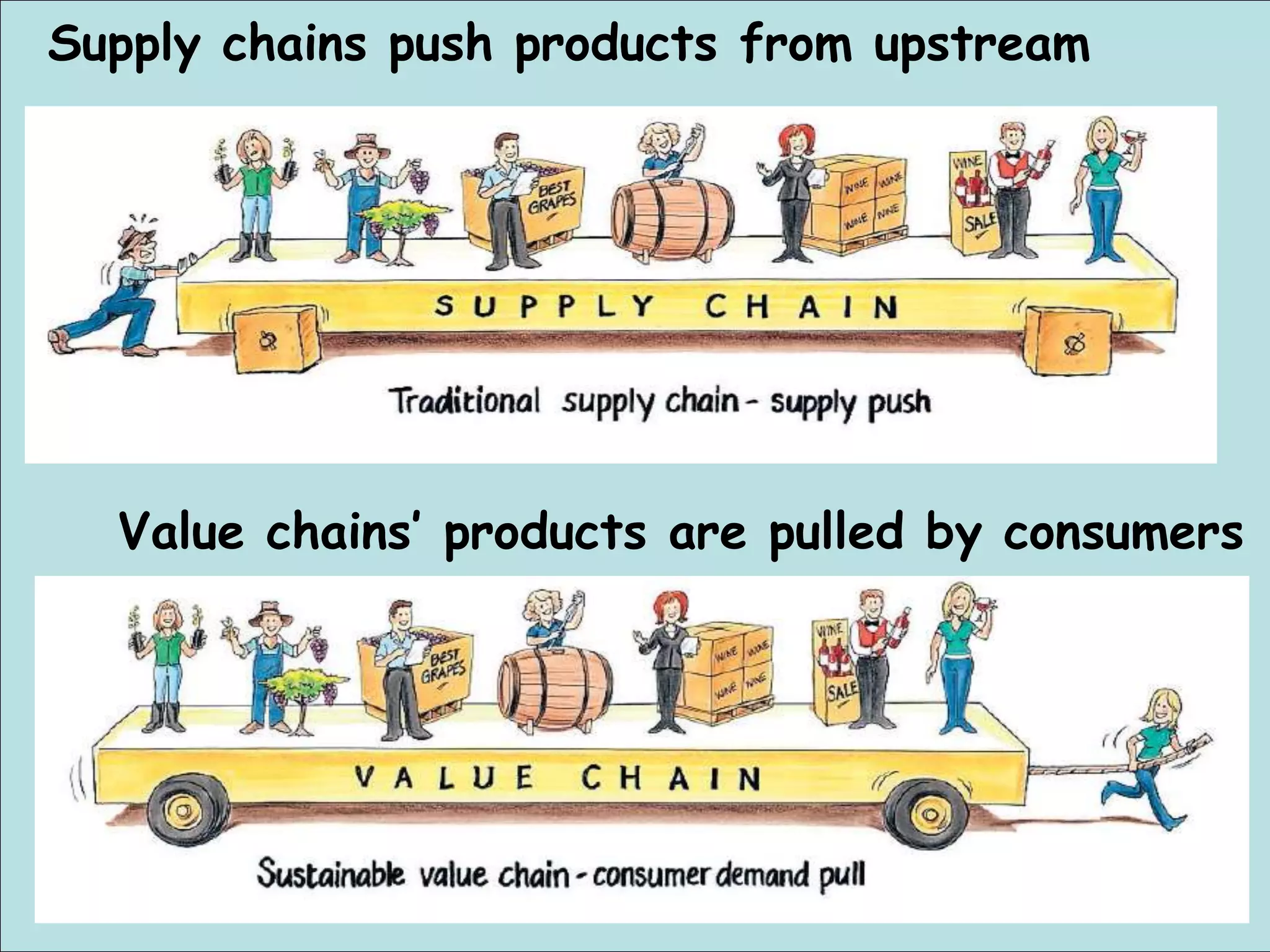

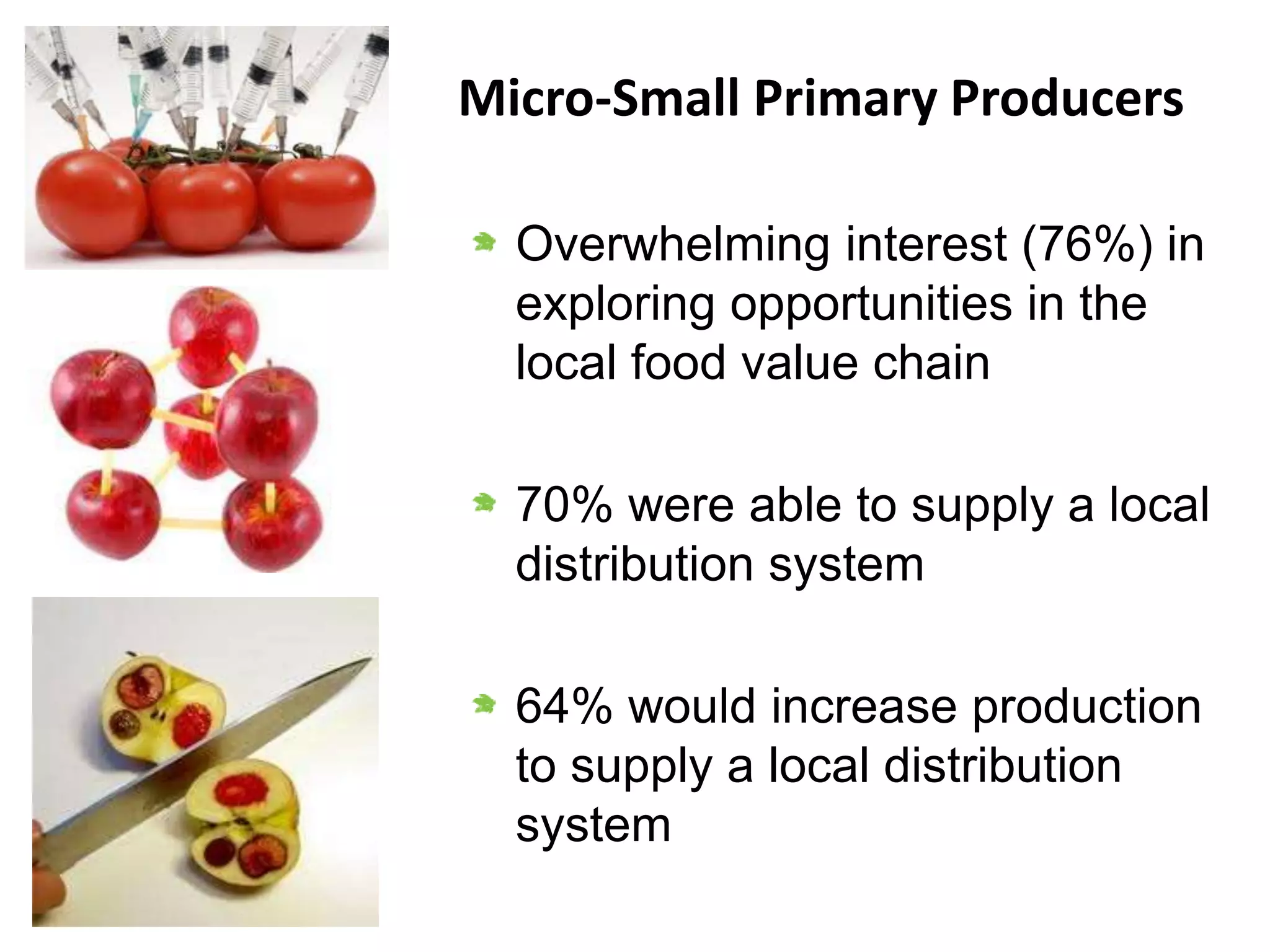

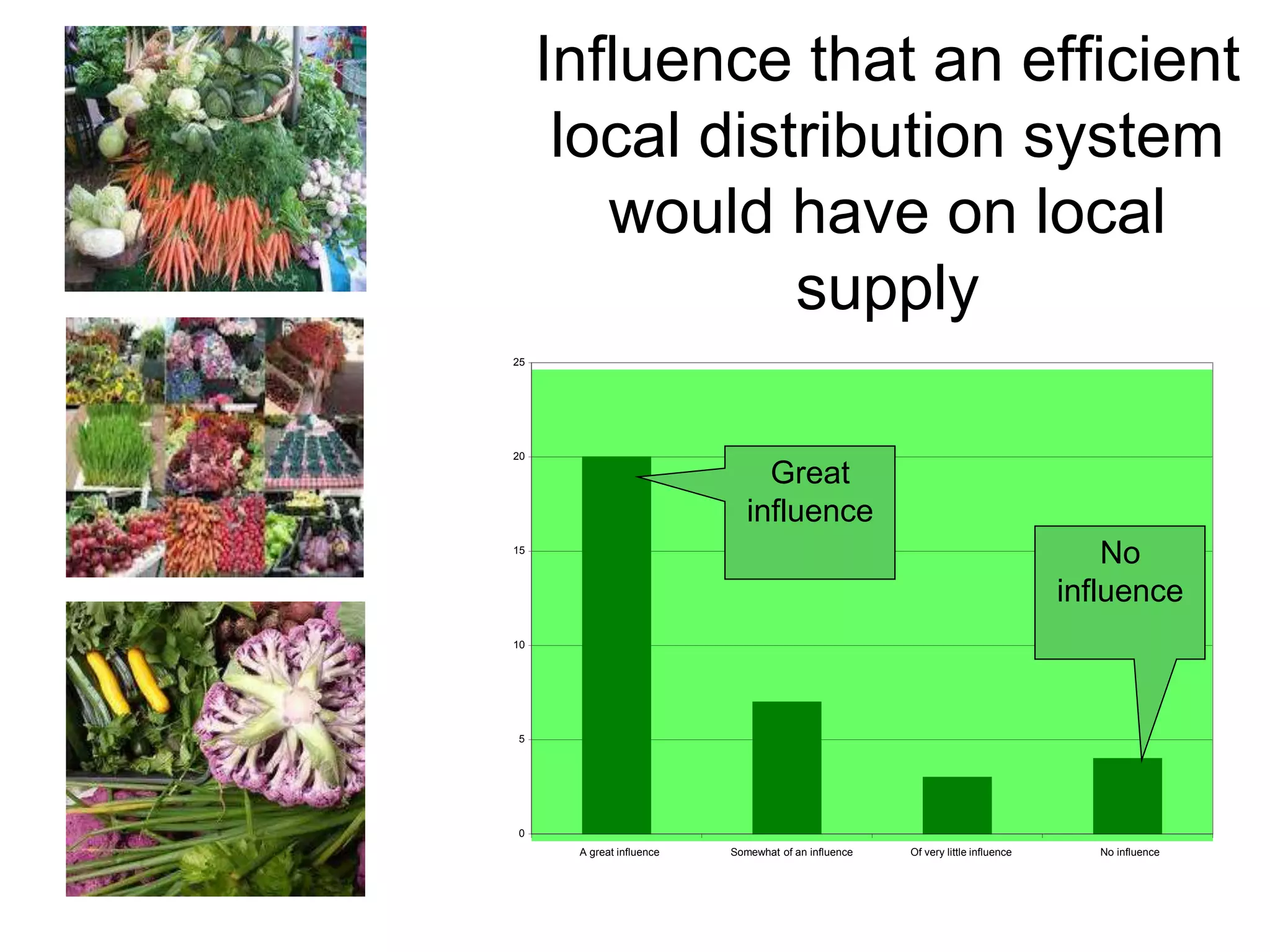

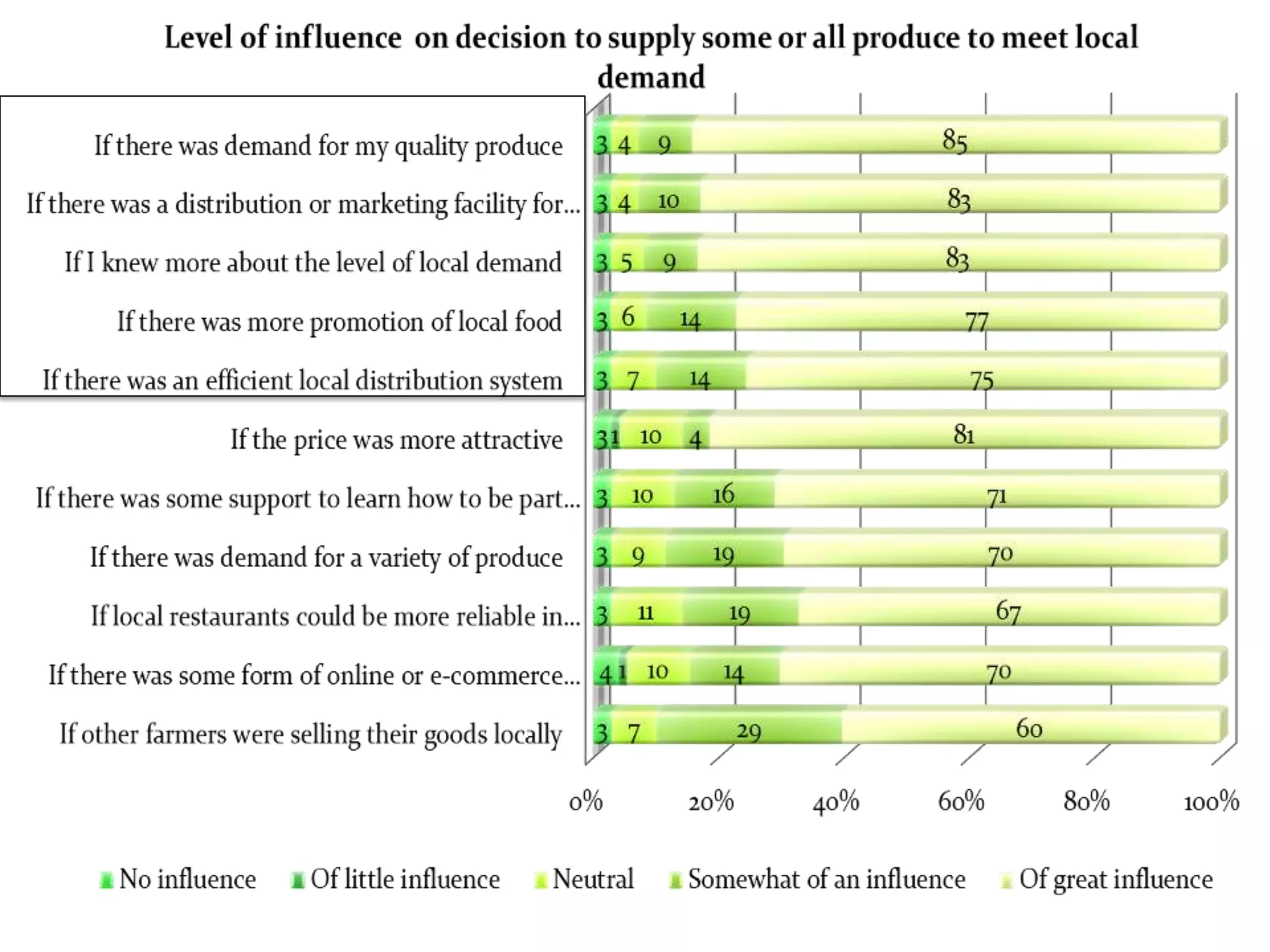

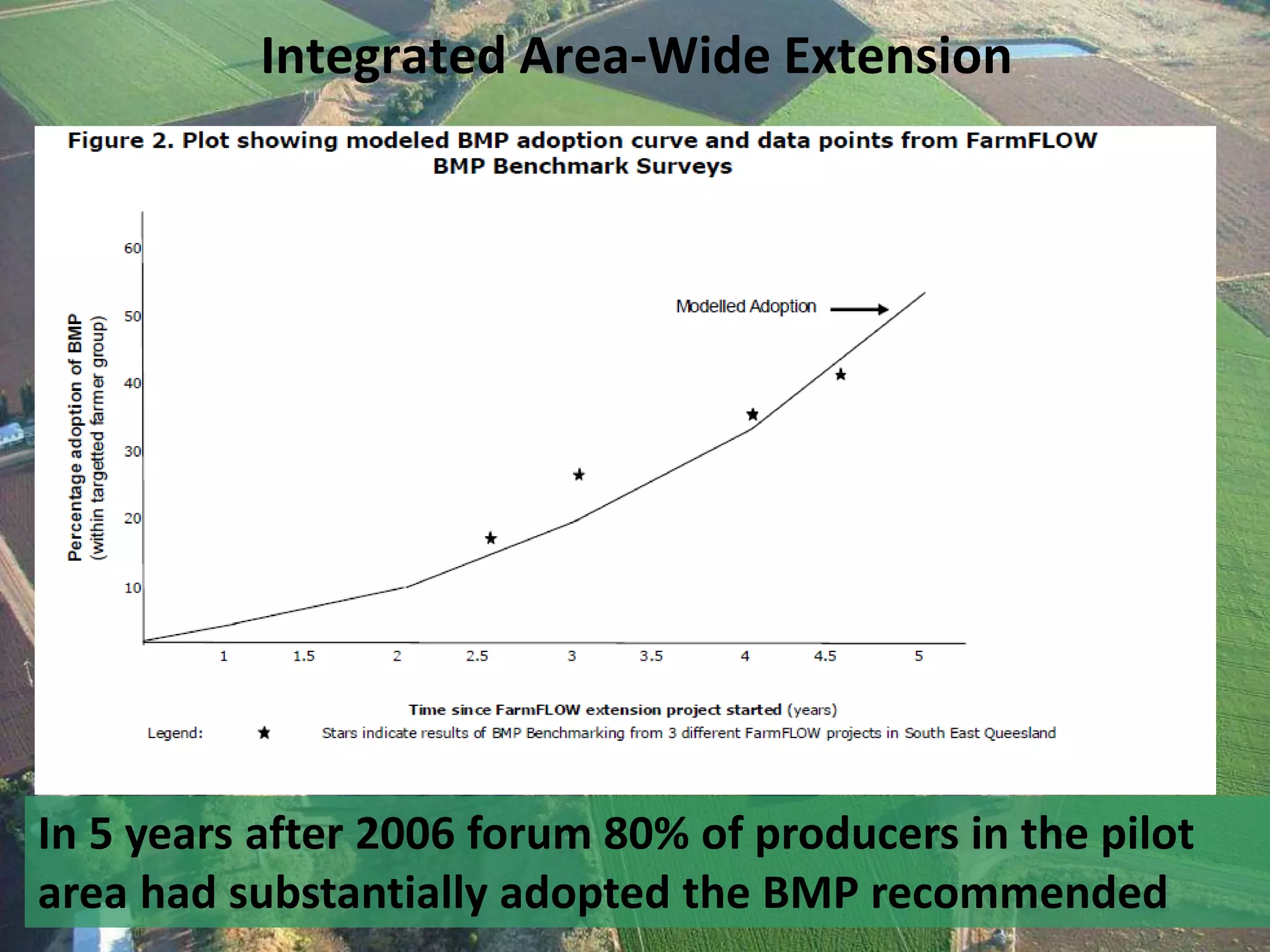

The document discusses how fragmented peri-urban agricultural systems can be reconfigured to achieve integrated social, economic, and environmental outcomes. A 2006 forum found that a sustainable future was unlikely with a "business as usual" approach, but over 60% likely if an integrated extension program provided incentives for best practices. By 2010, 73% of mid-scale farms feared the region's farming future. The document advocates a collaborative service delivery model involving government, universities, and industry to support farmers through business development, training, and regional branding.