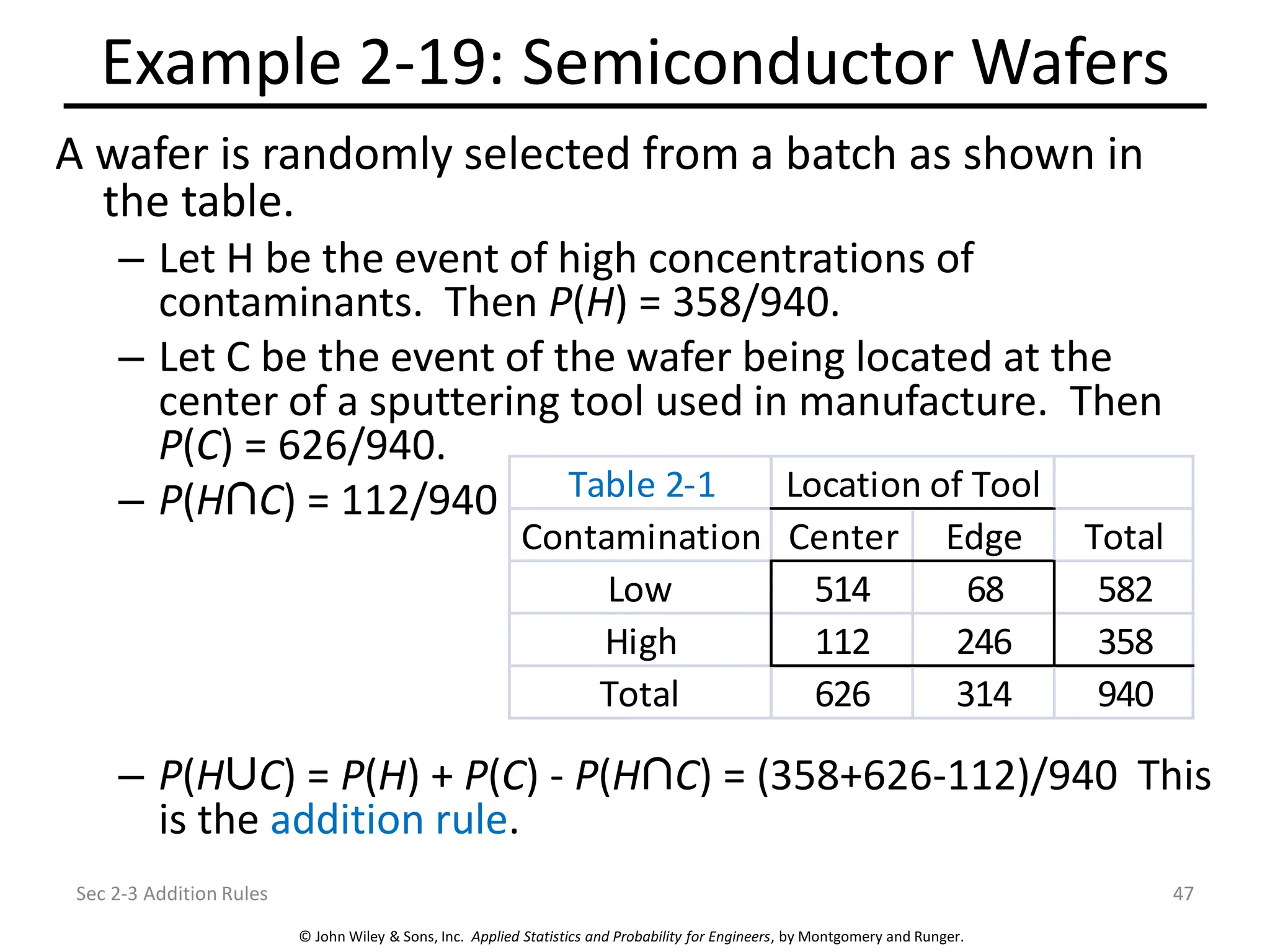

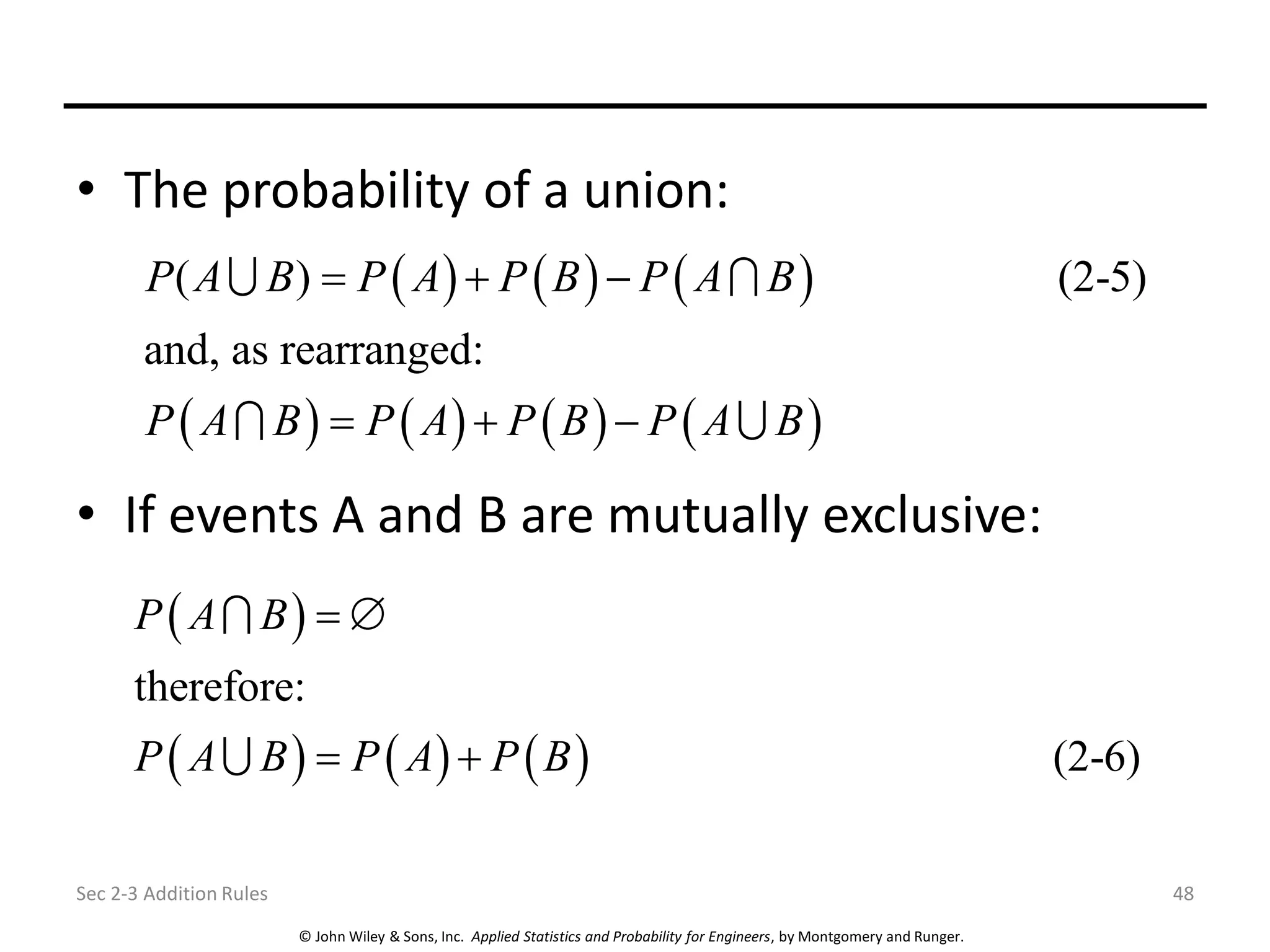

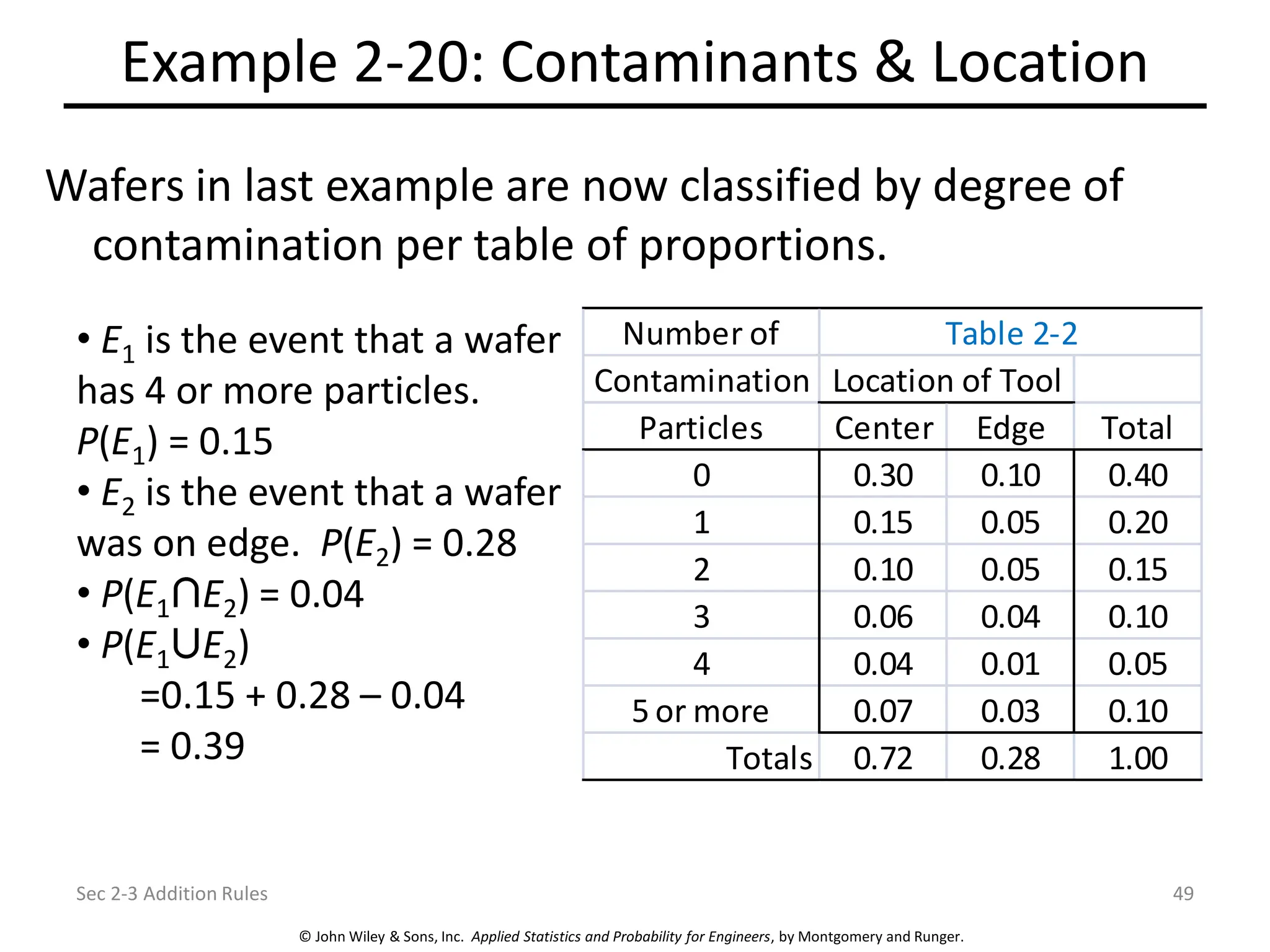

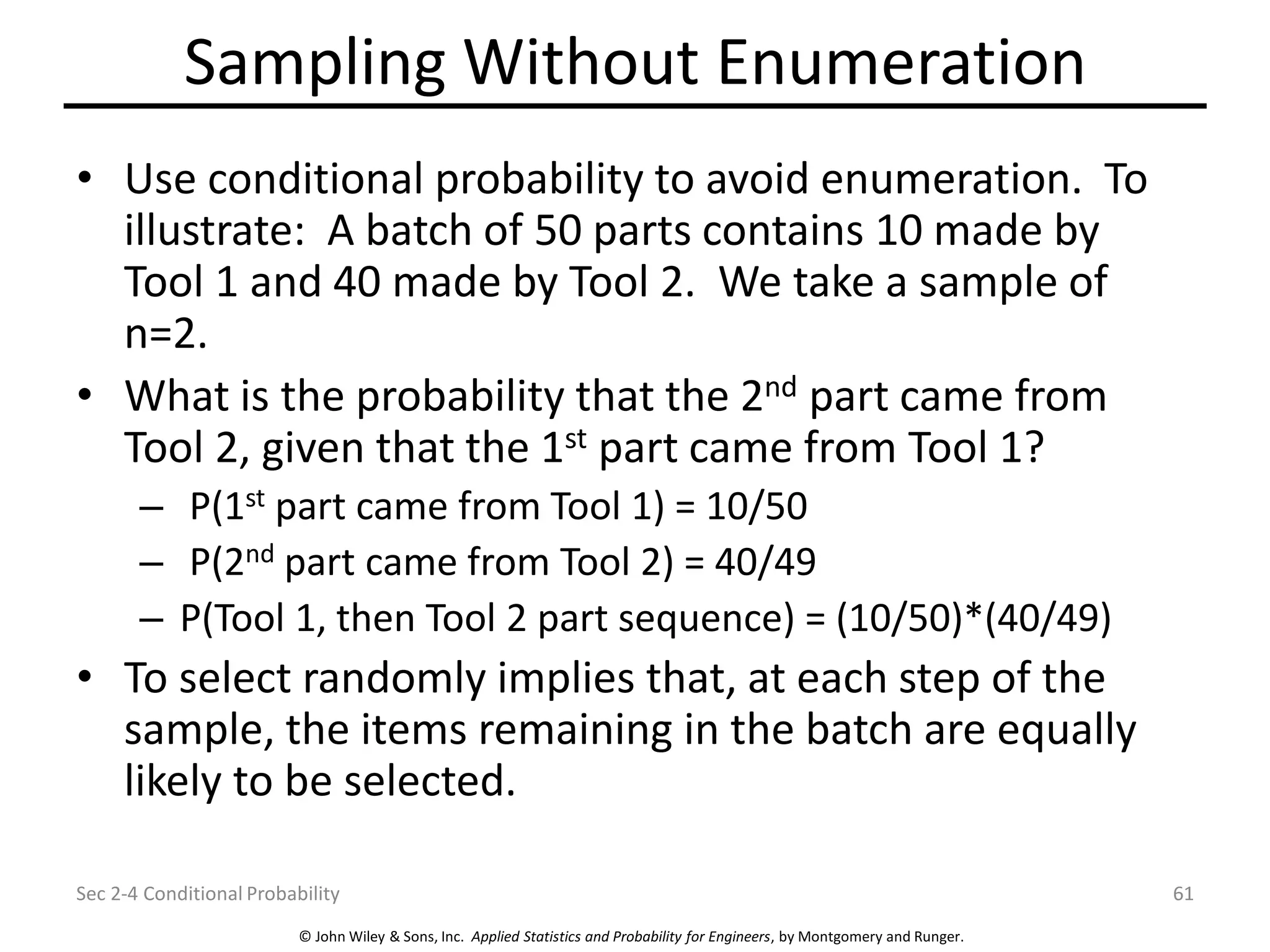

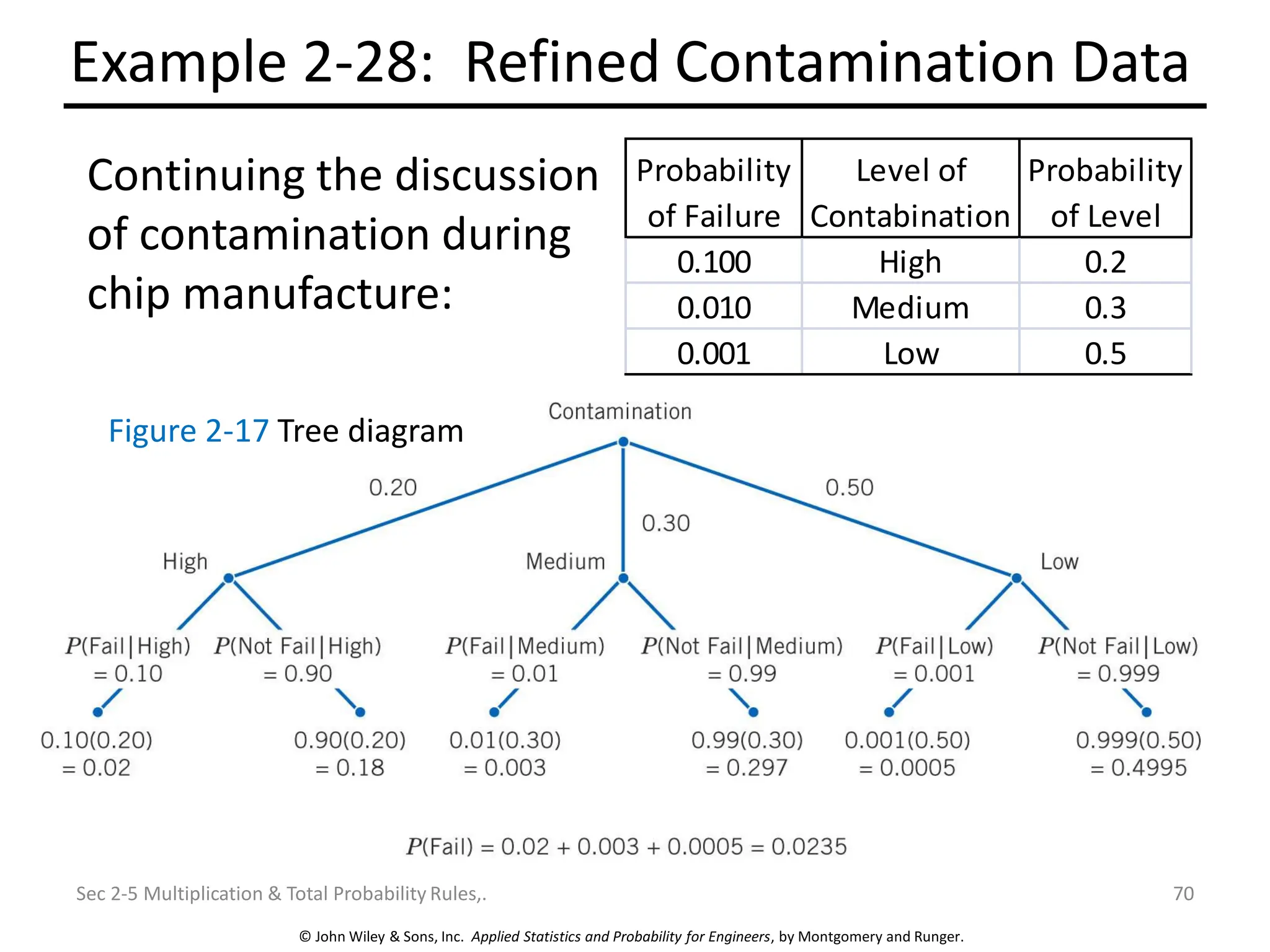

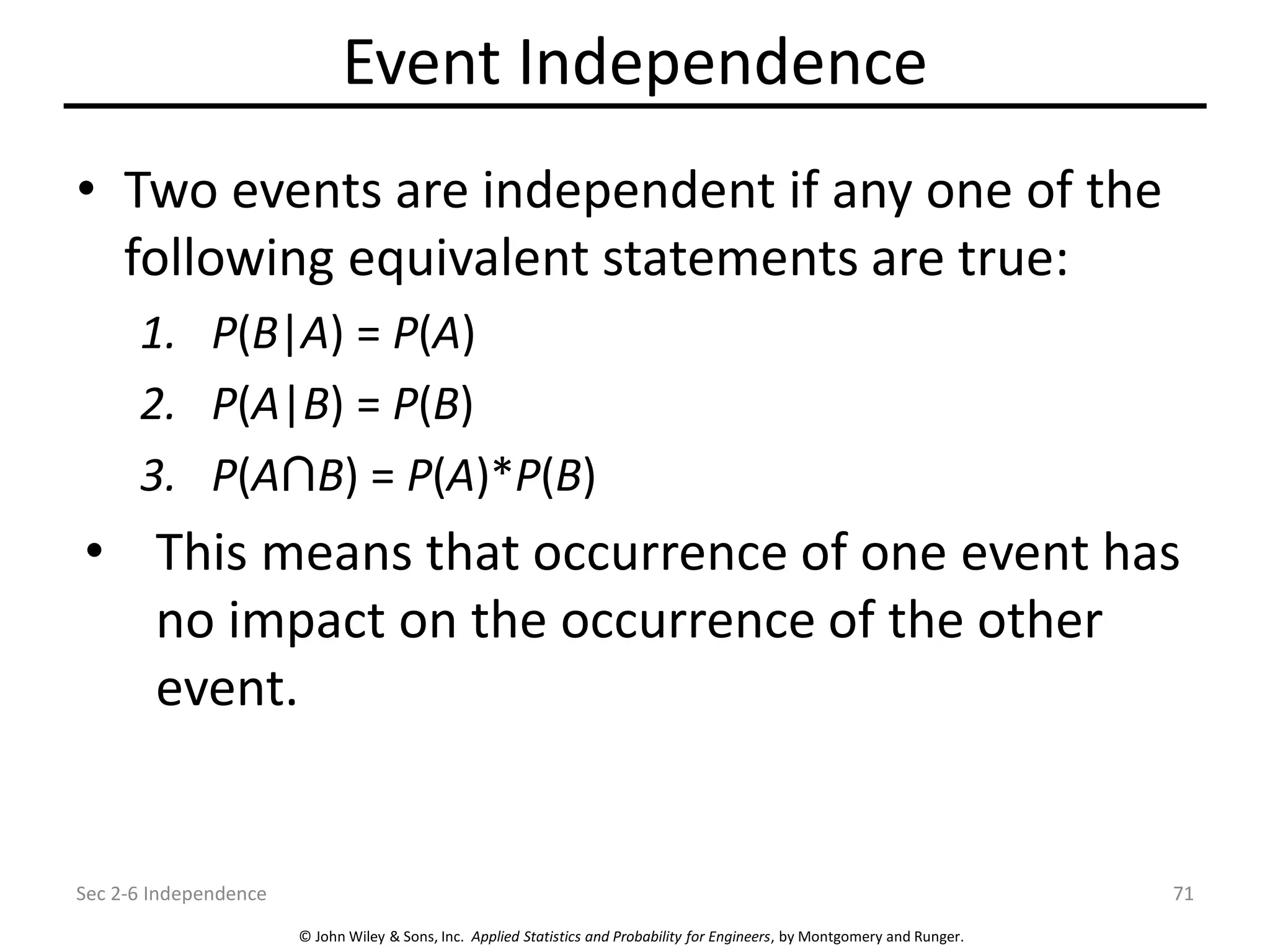

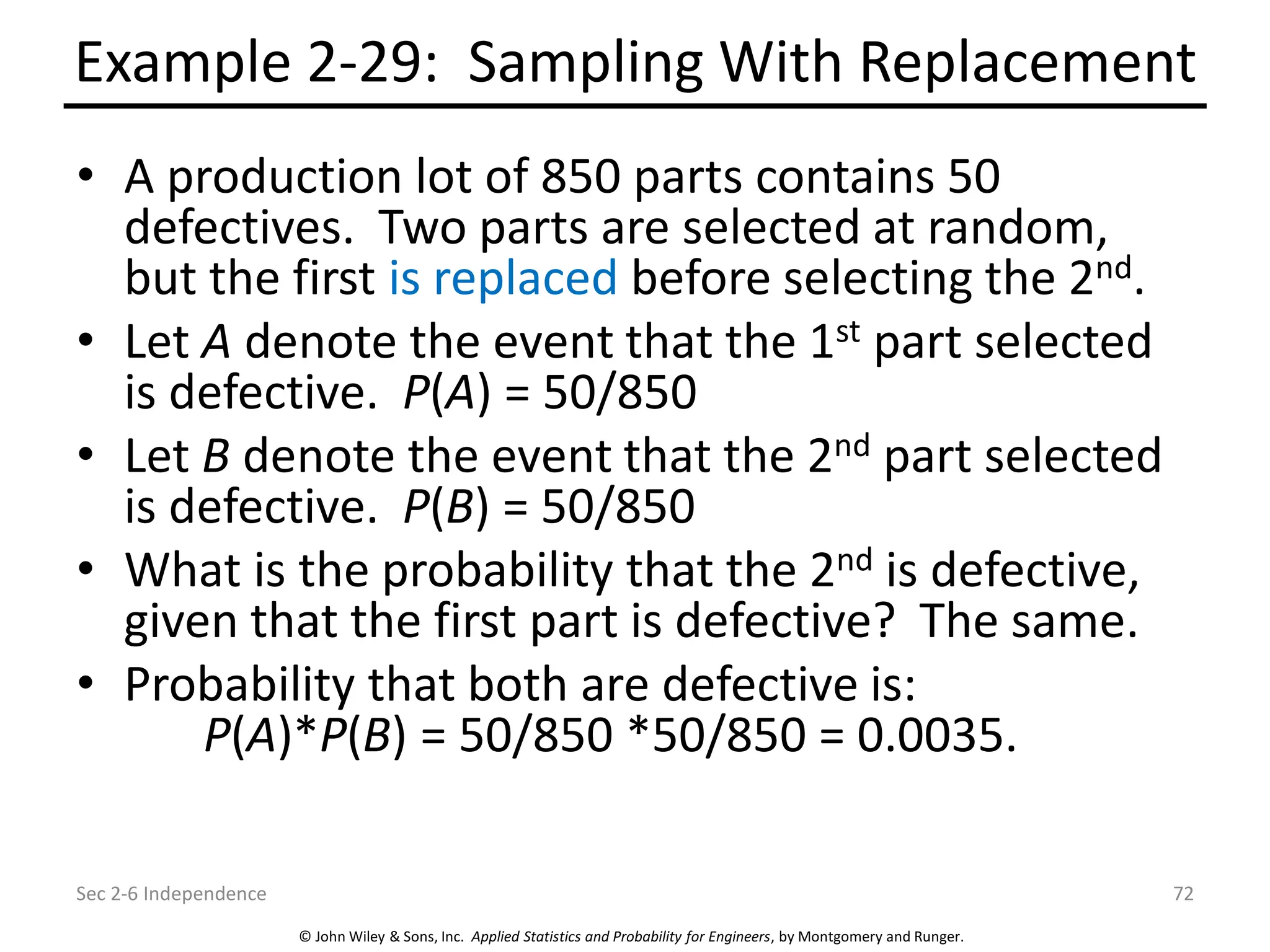

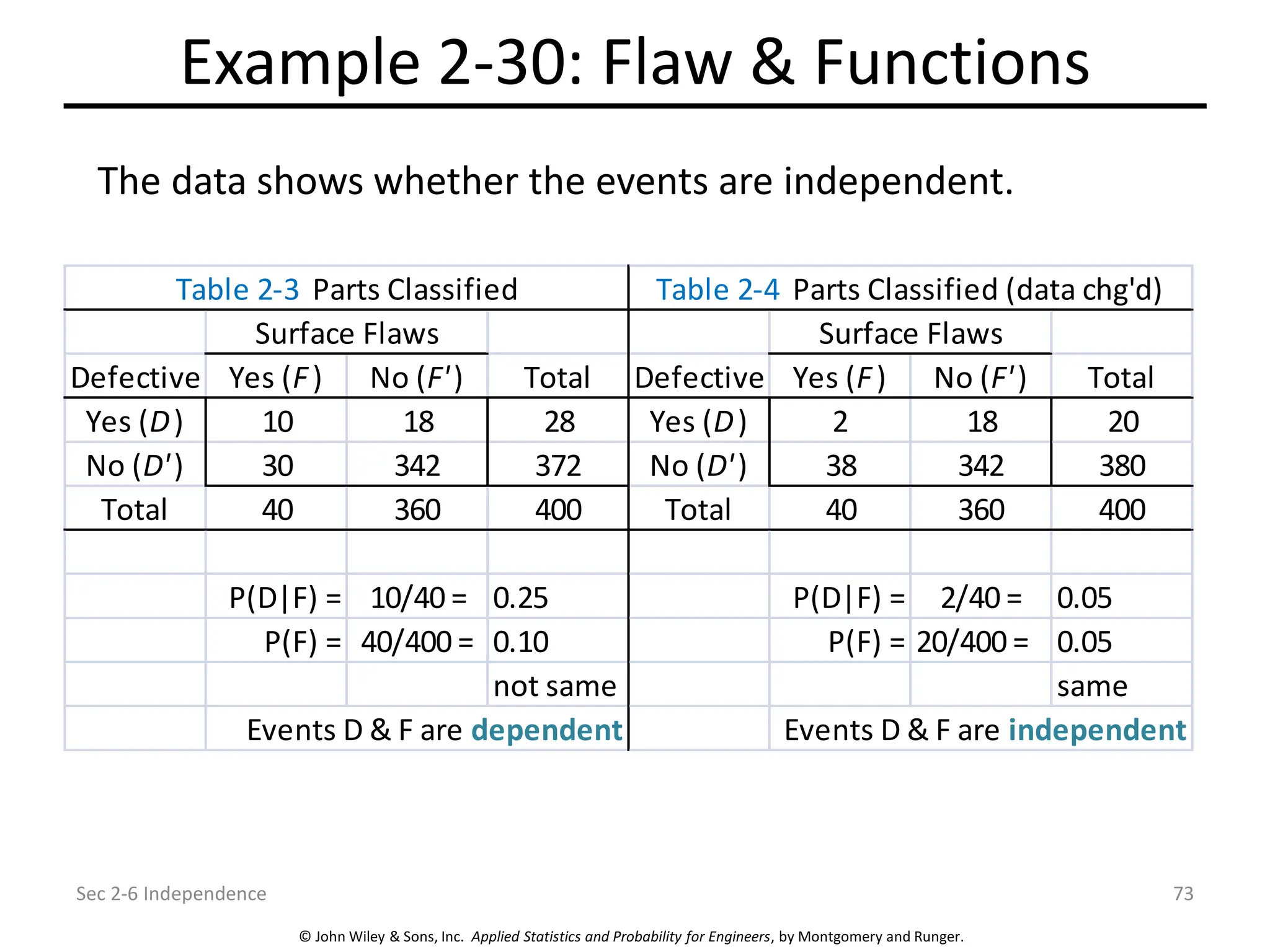

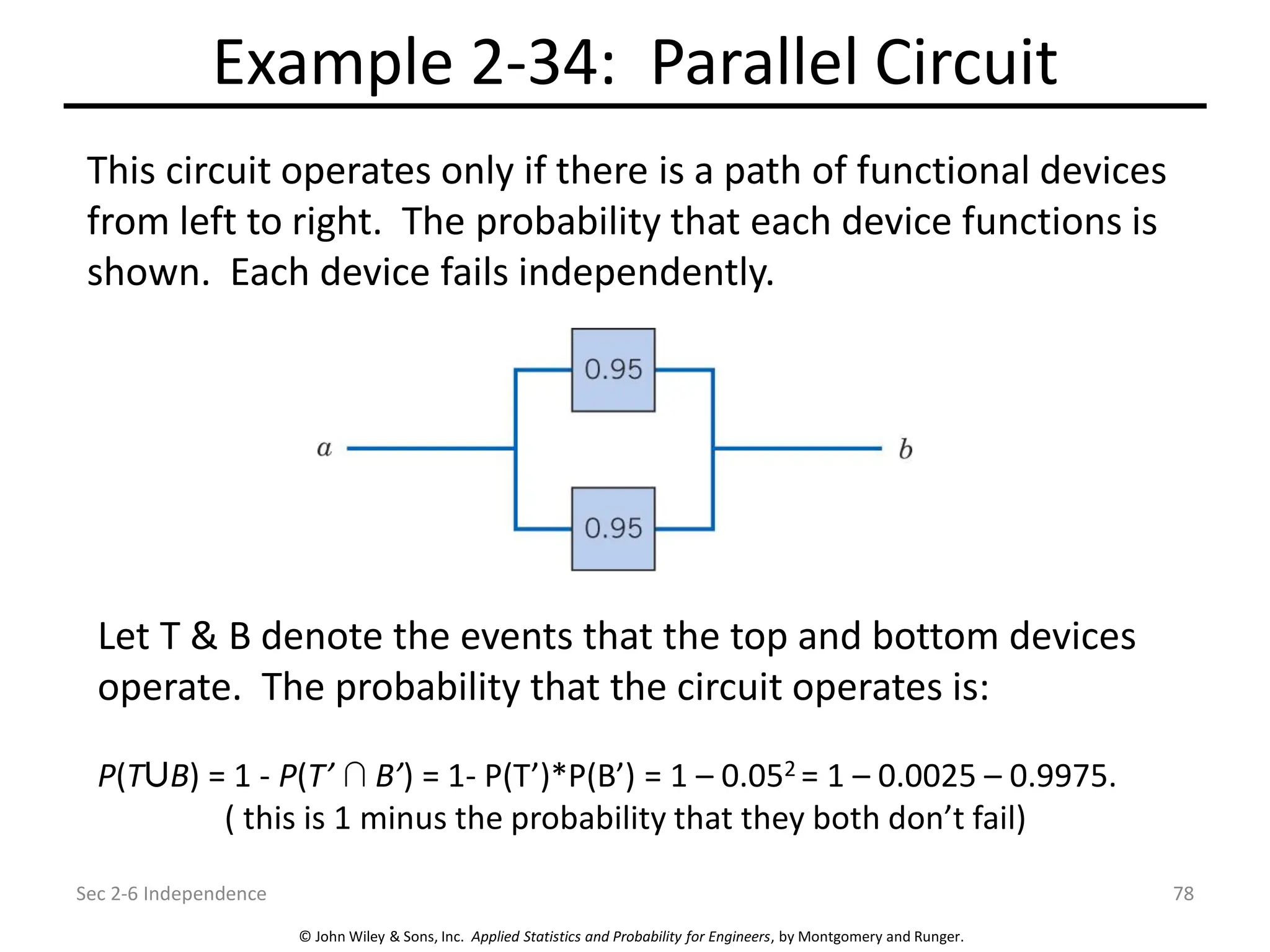

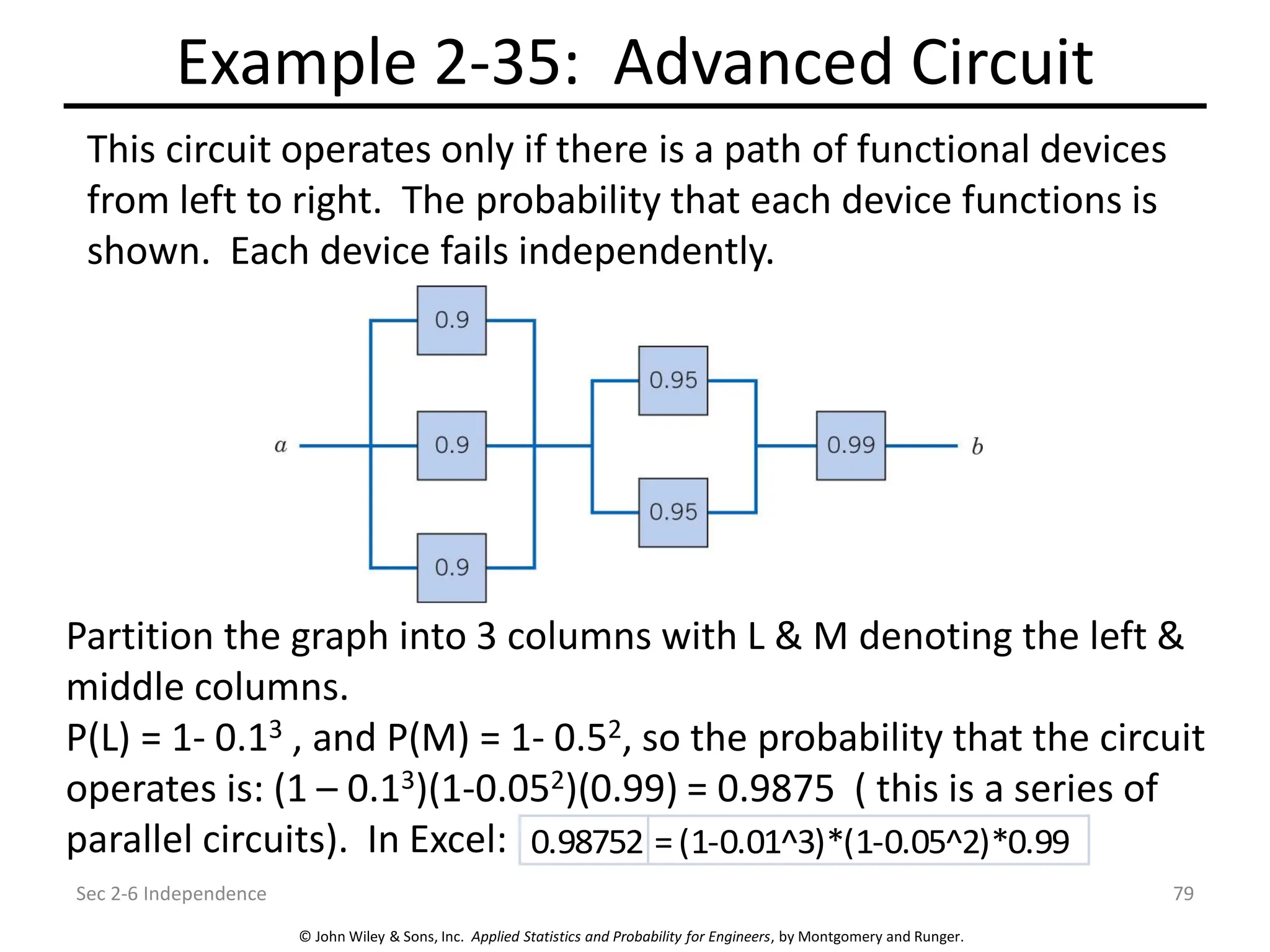

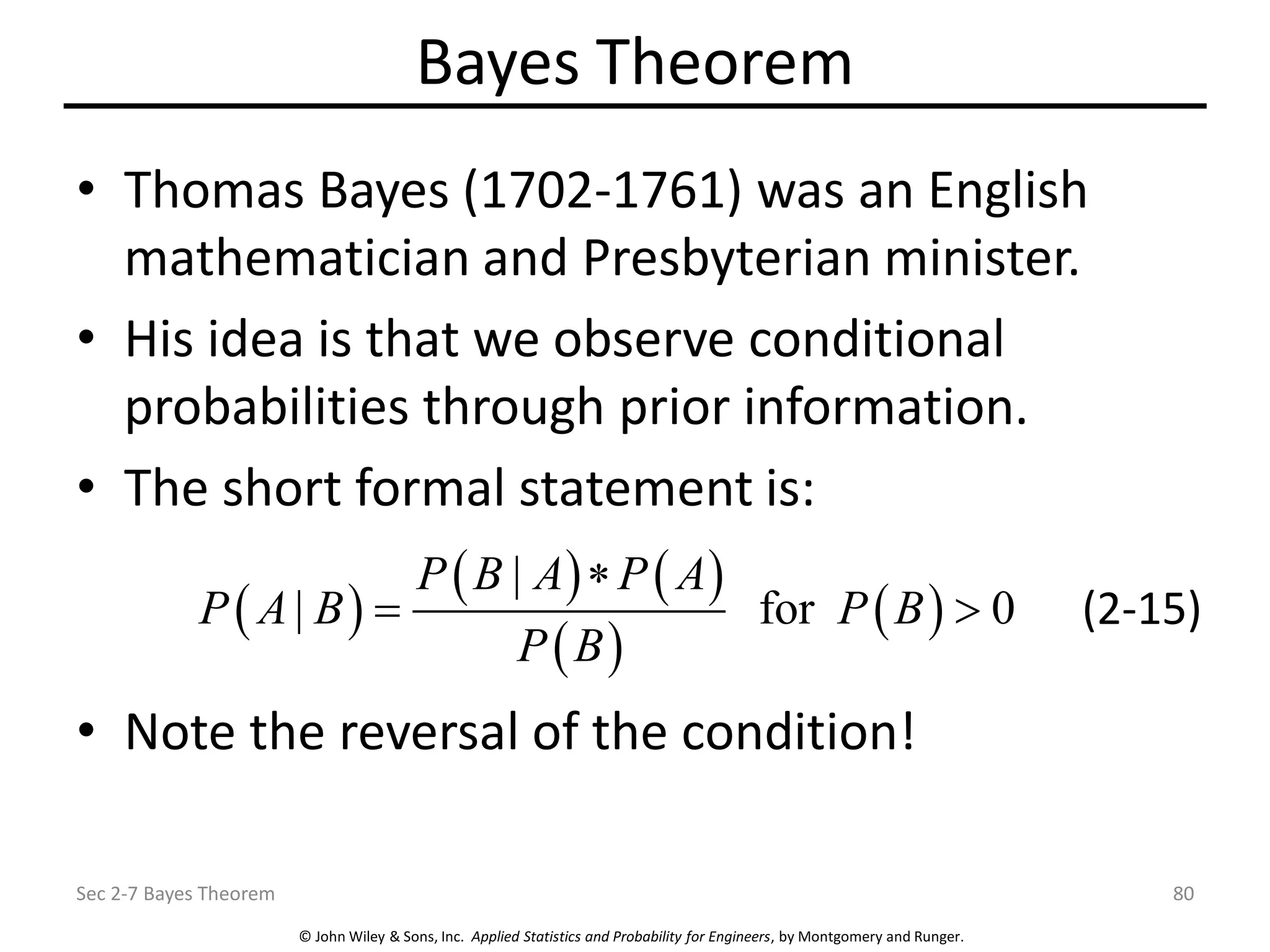

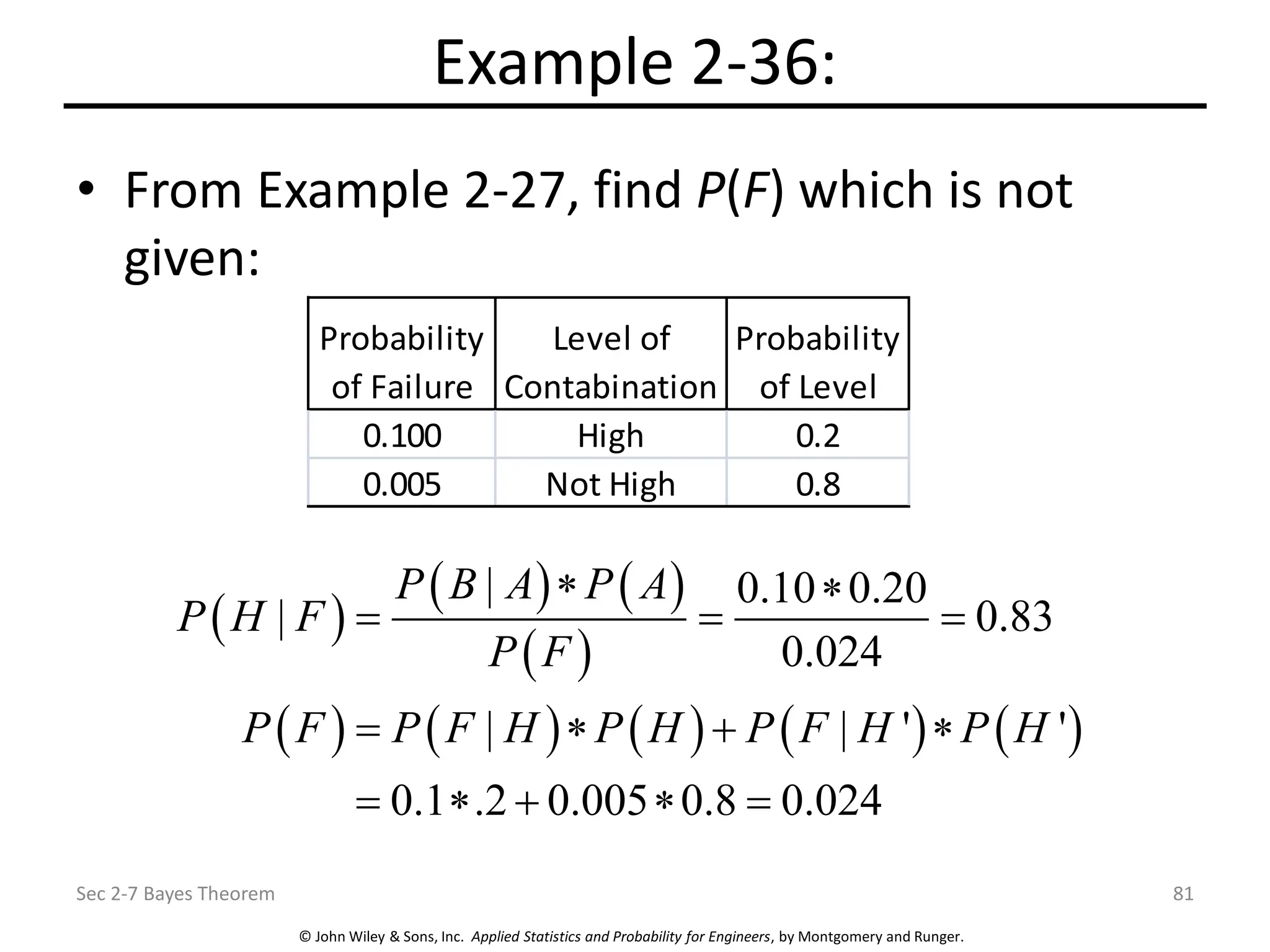

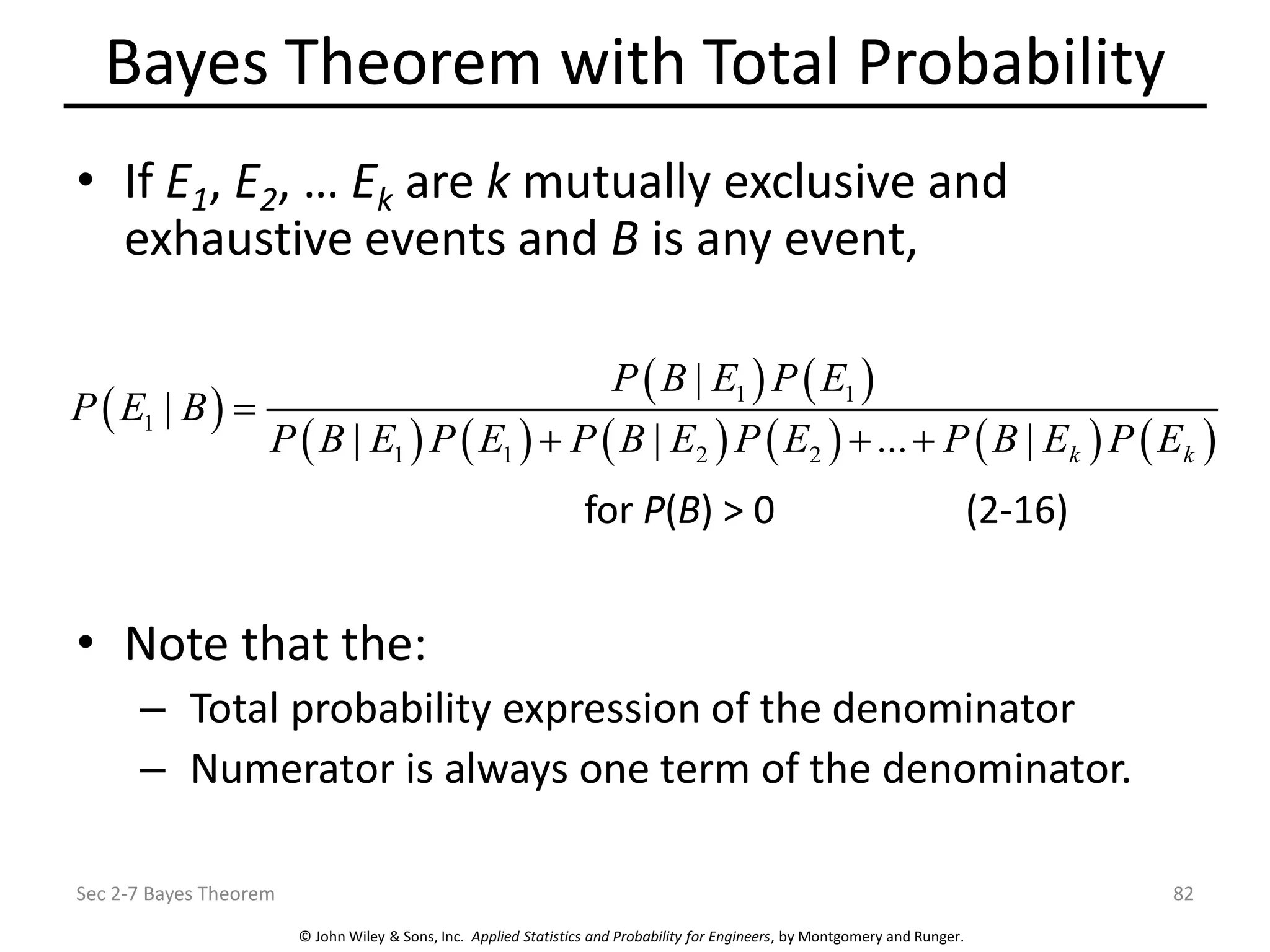

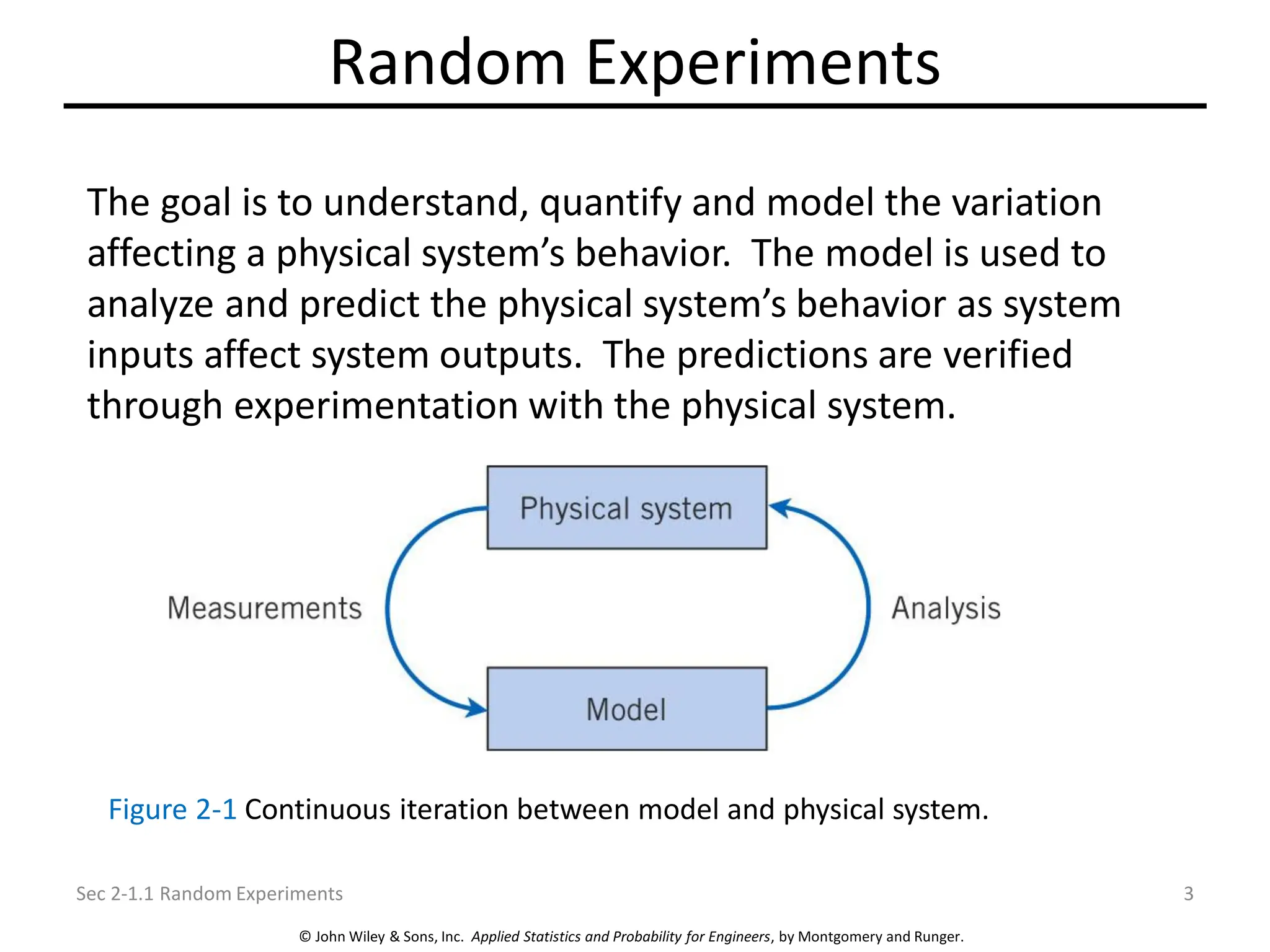

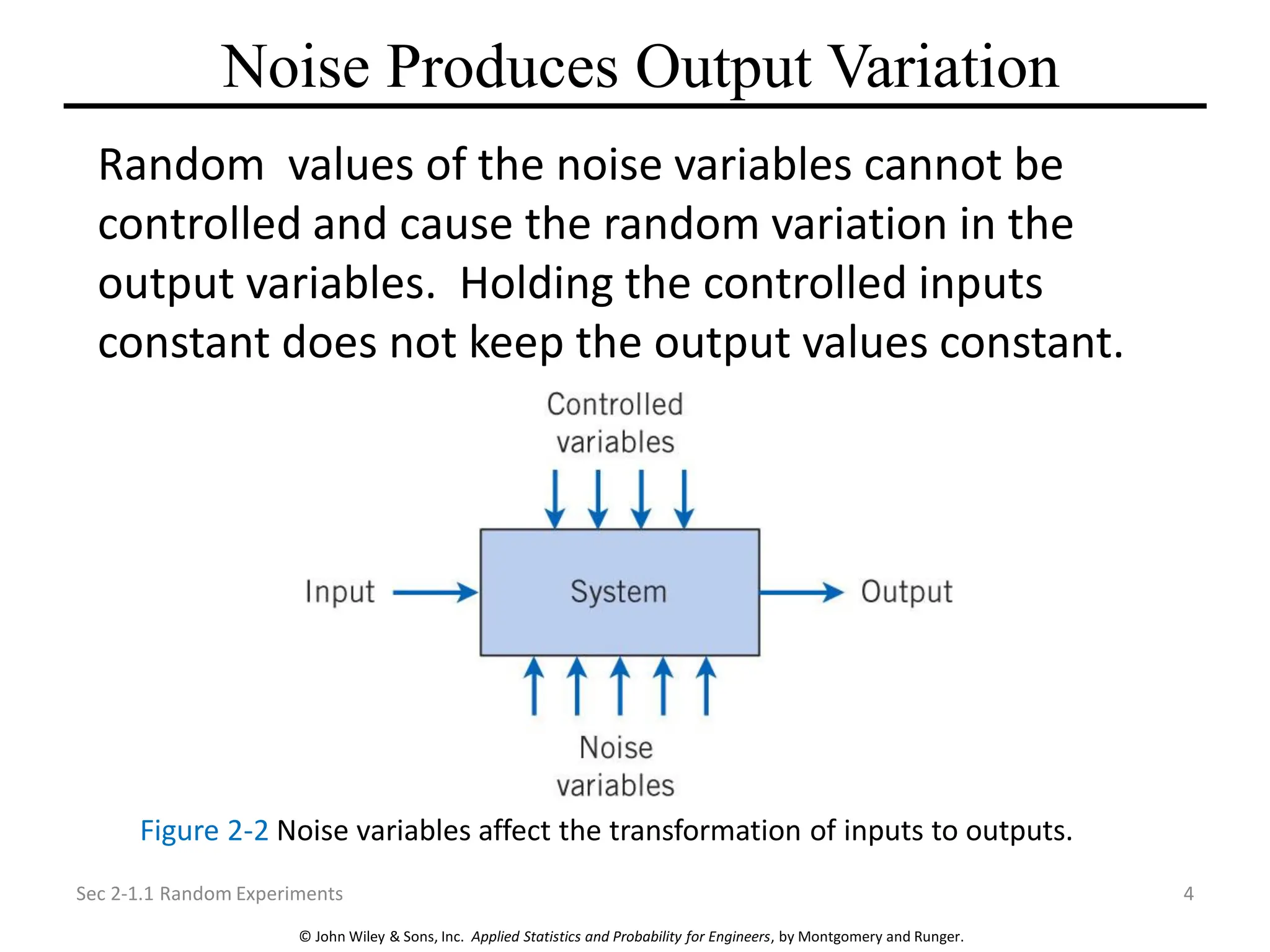

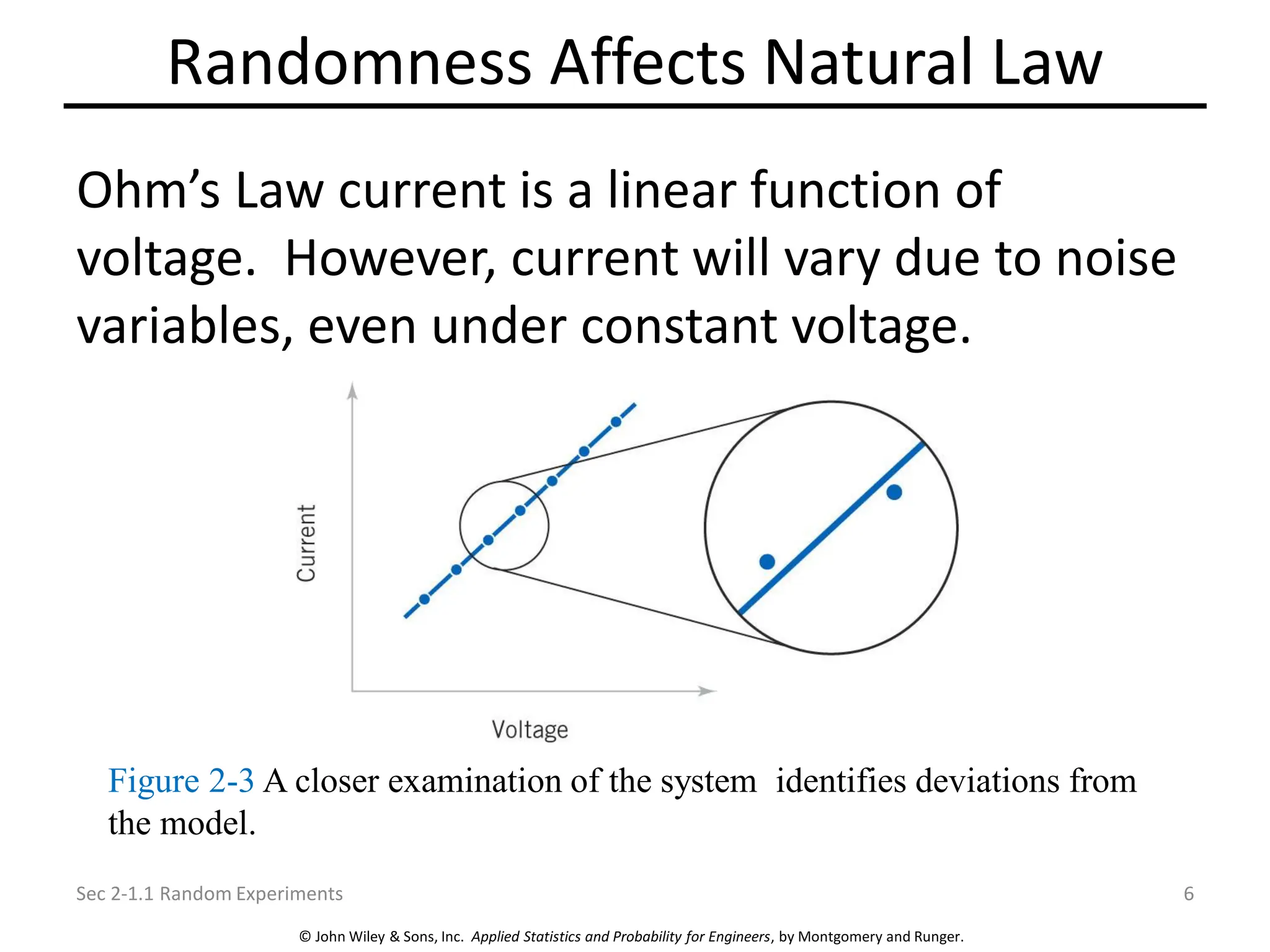

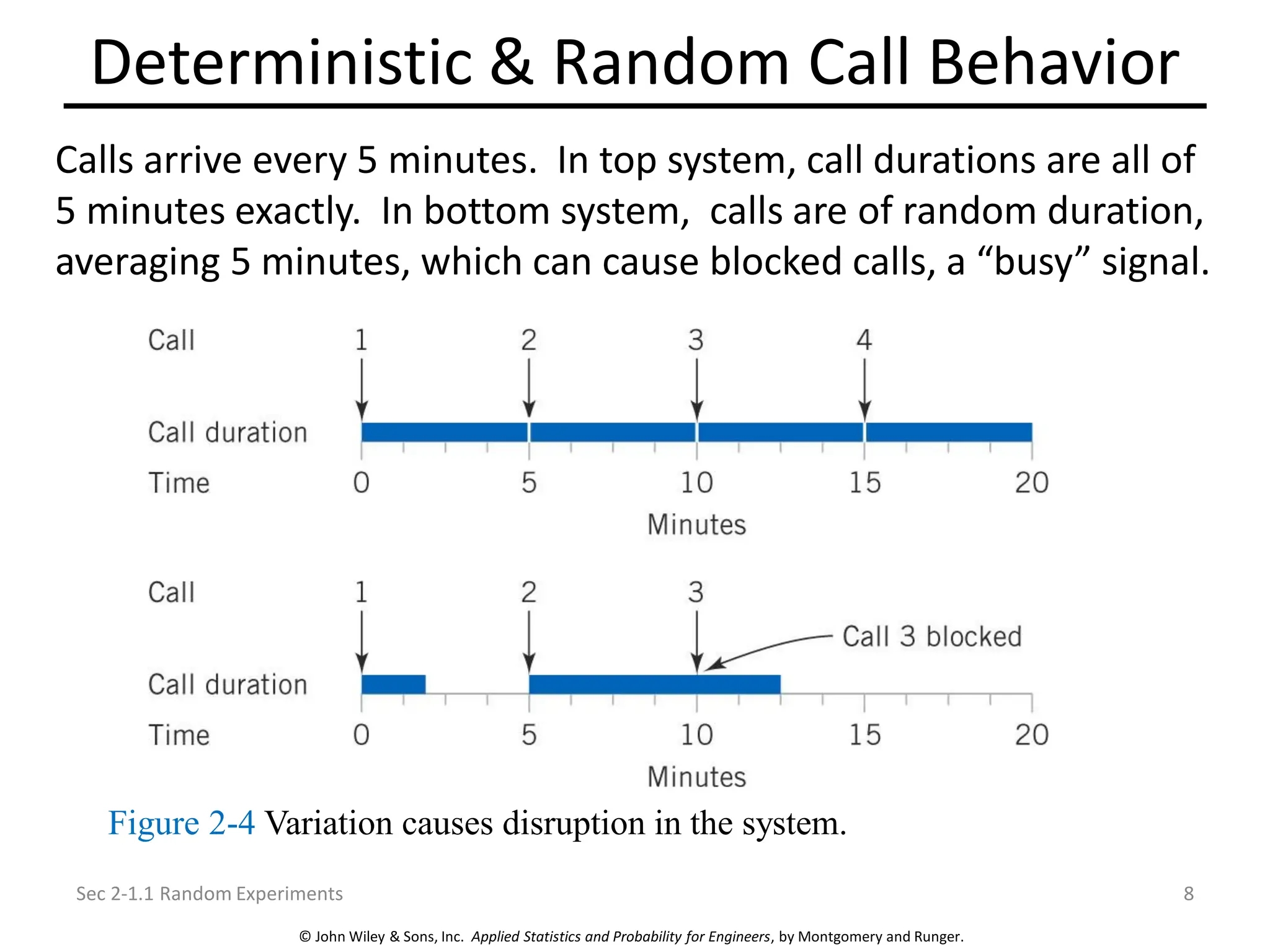

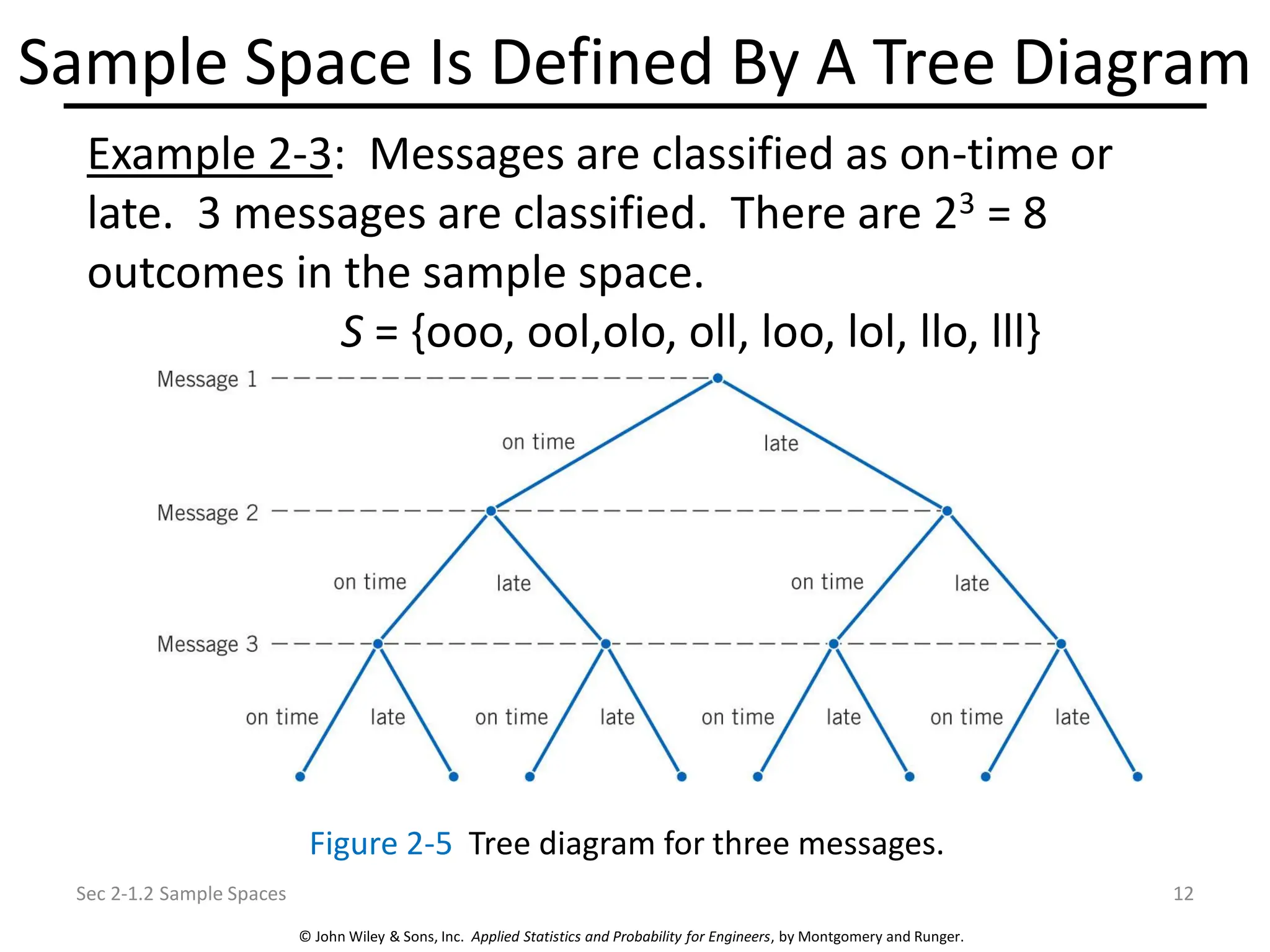

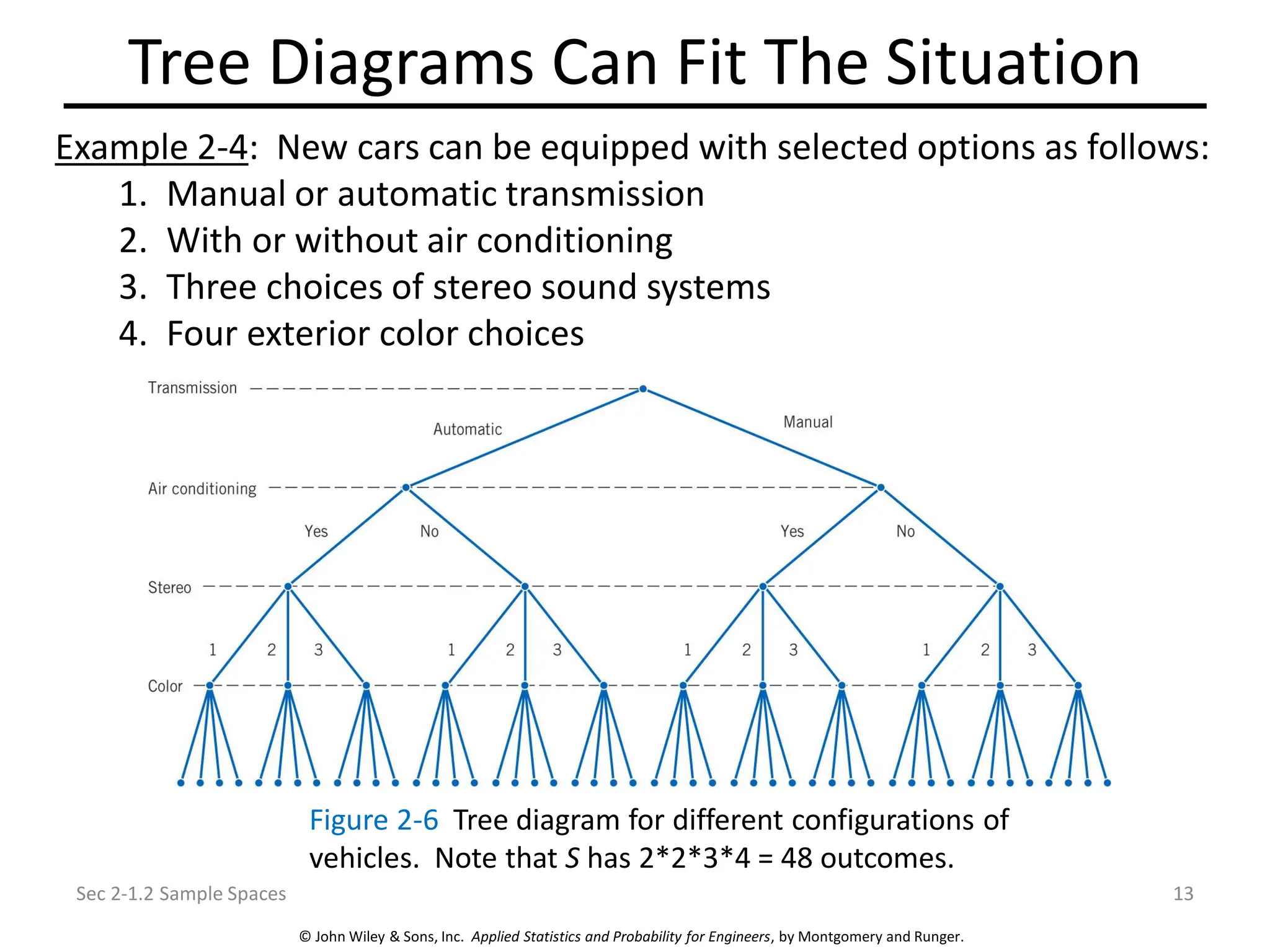

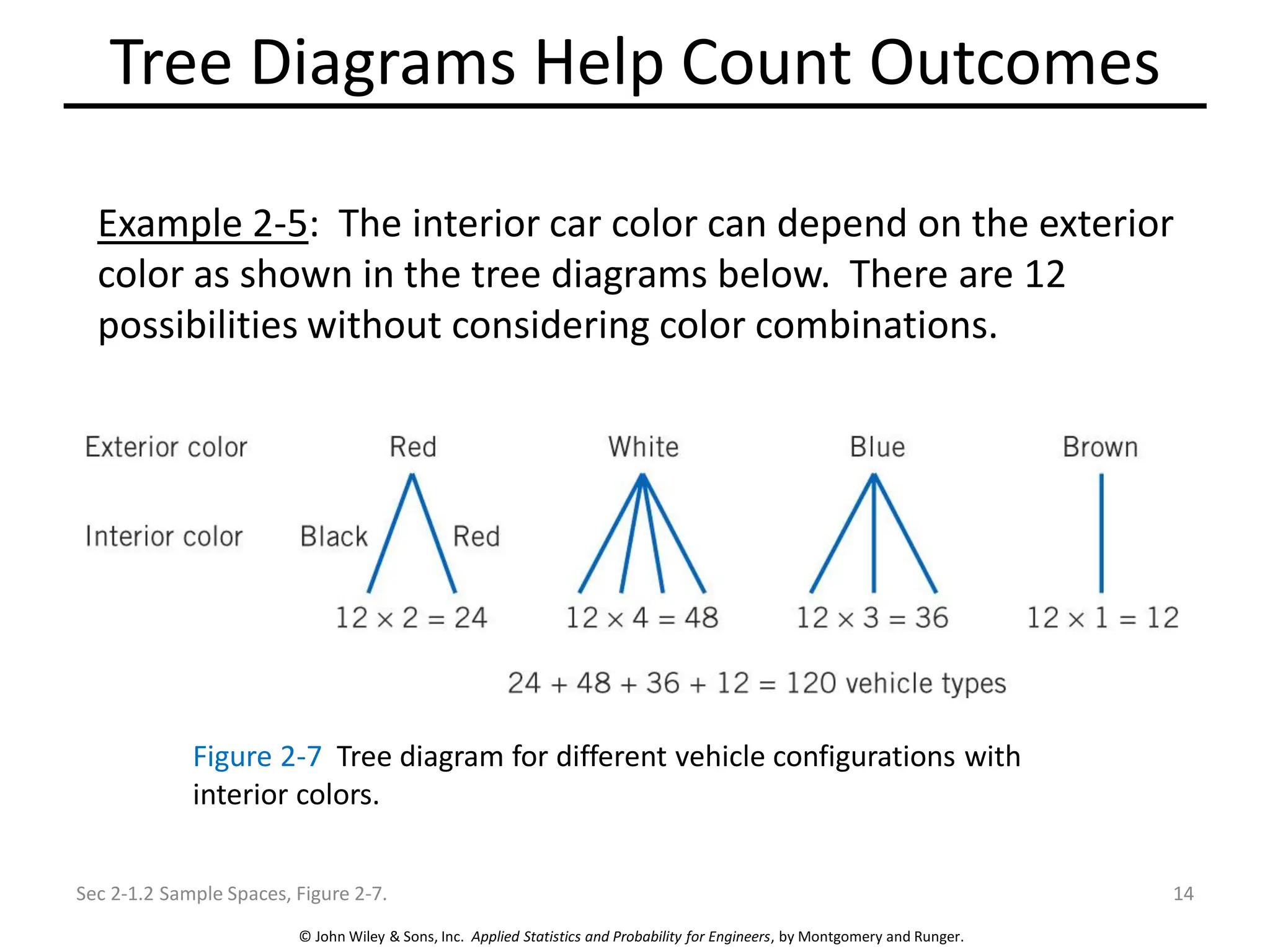

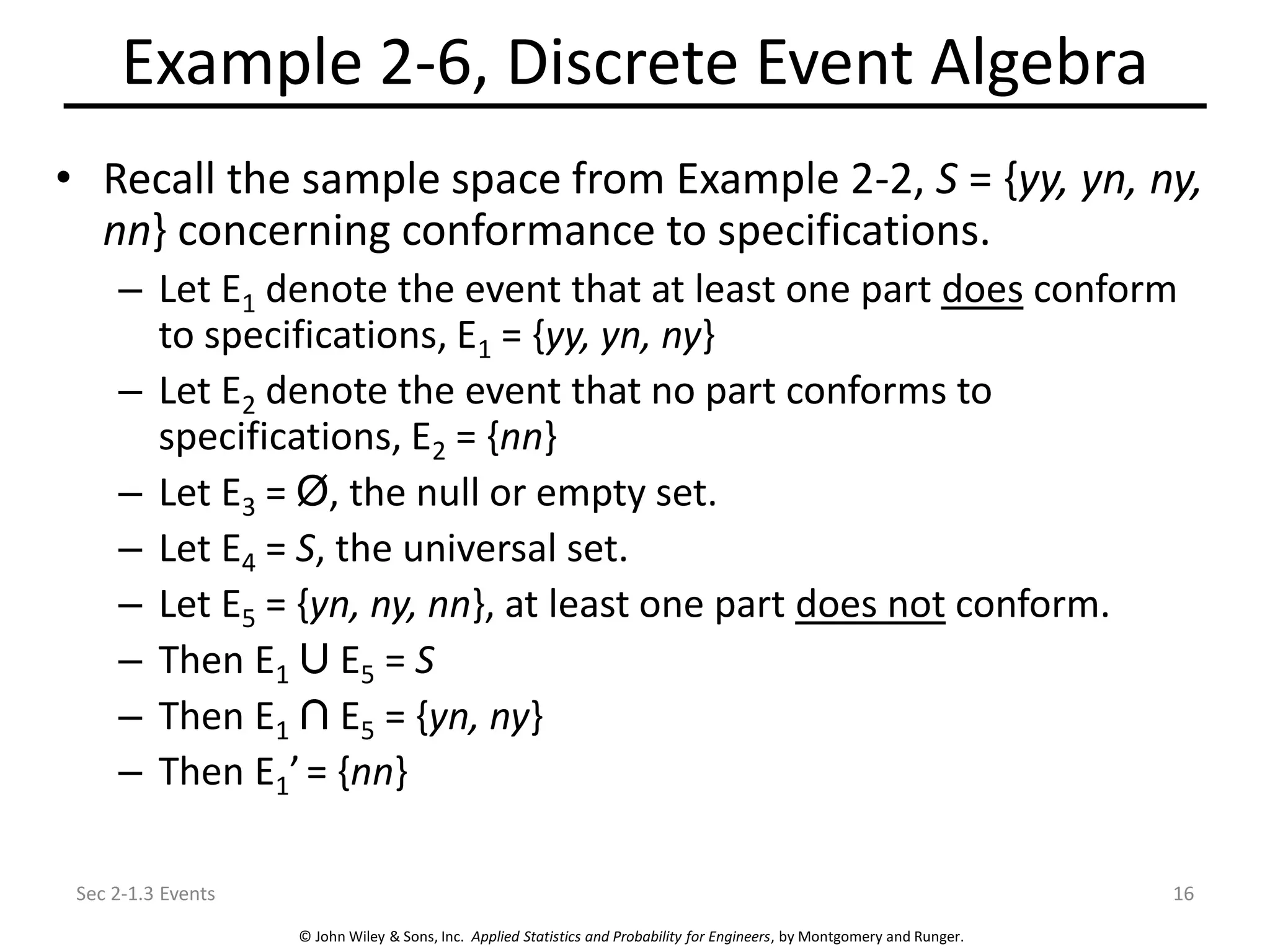

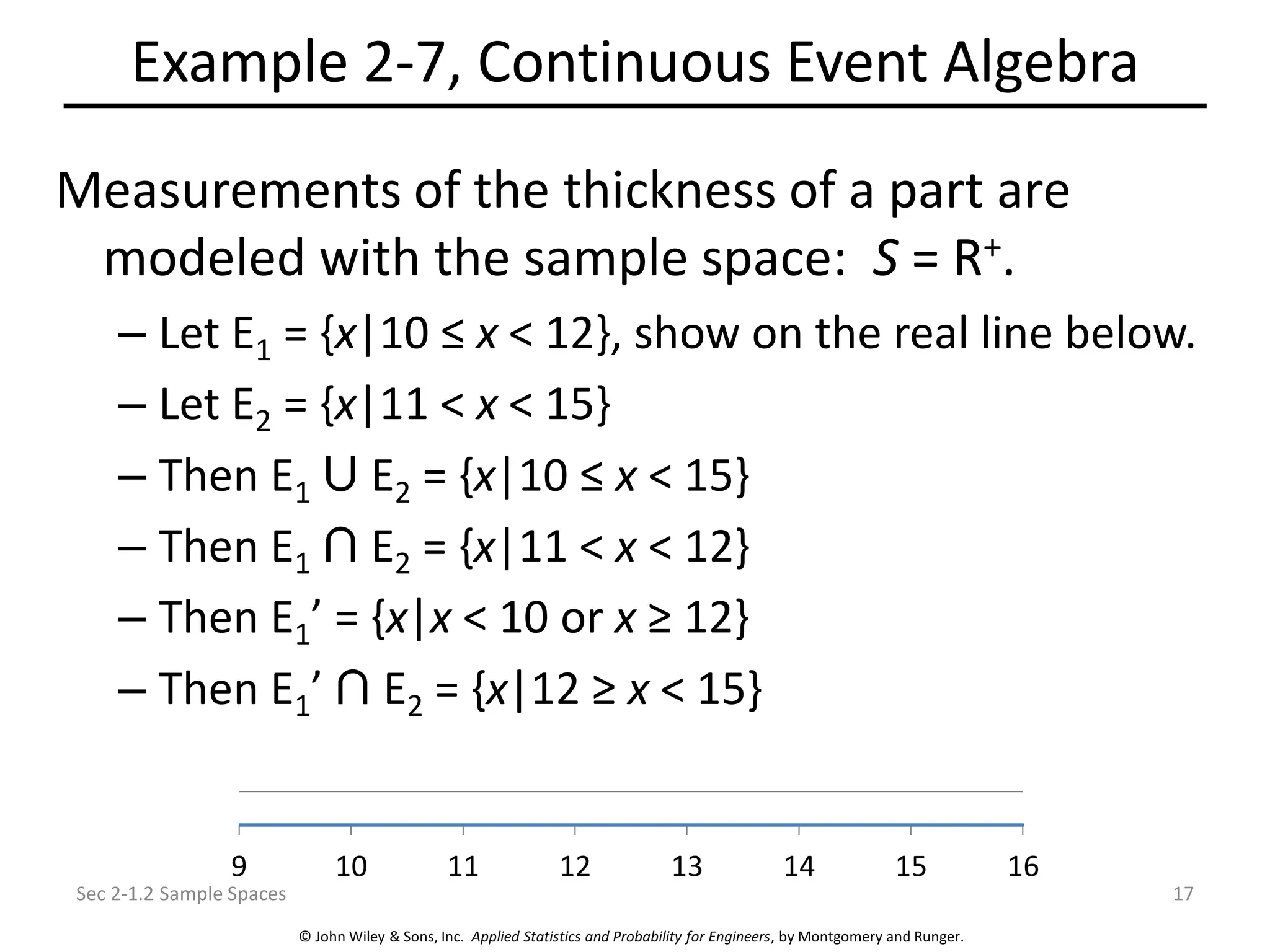

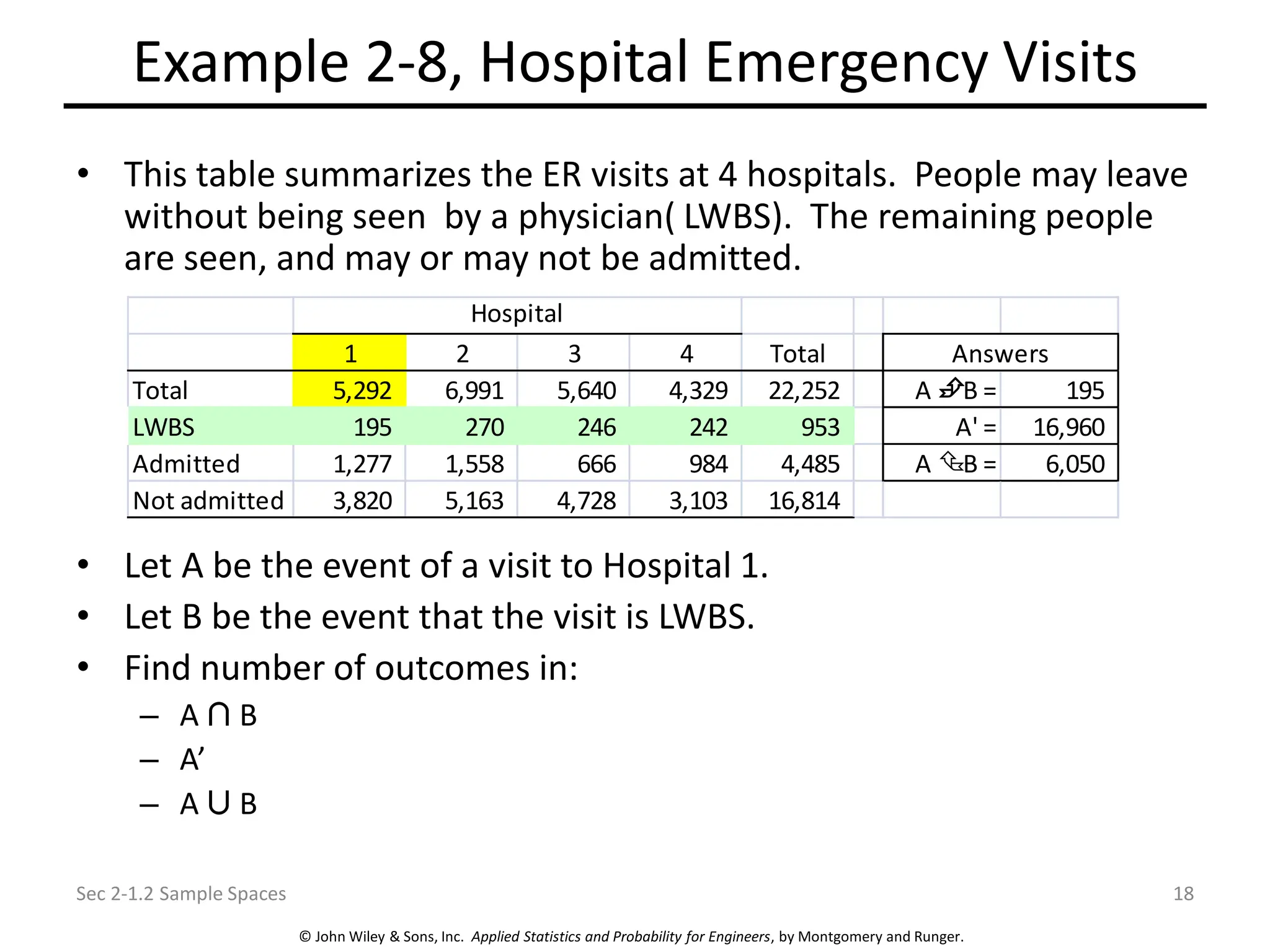

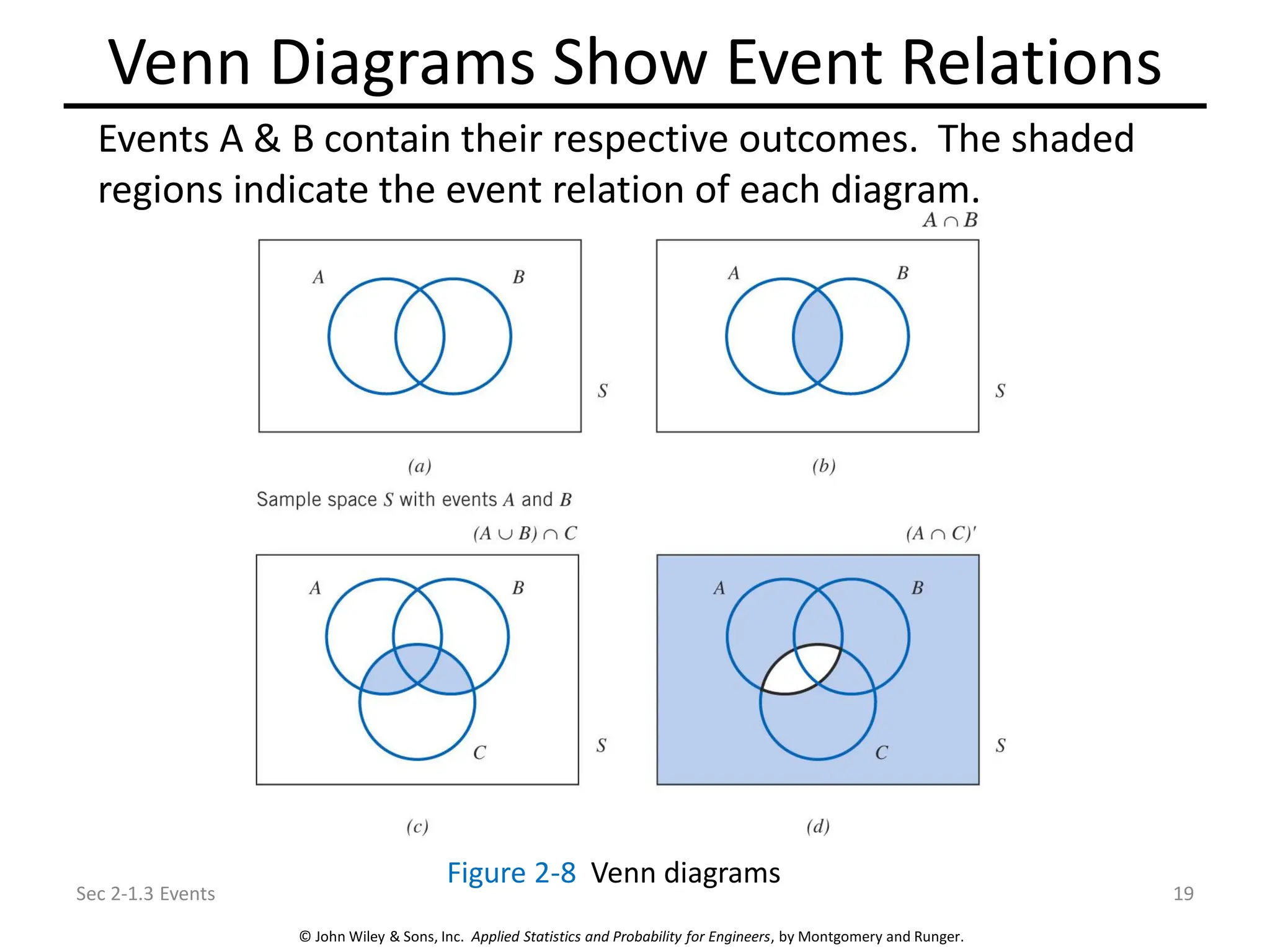

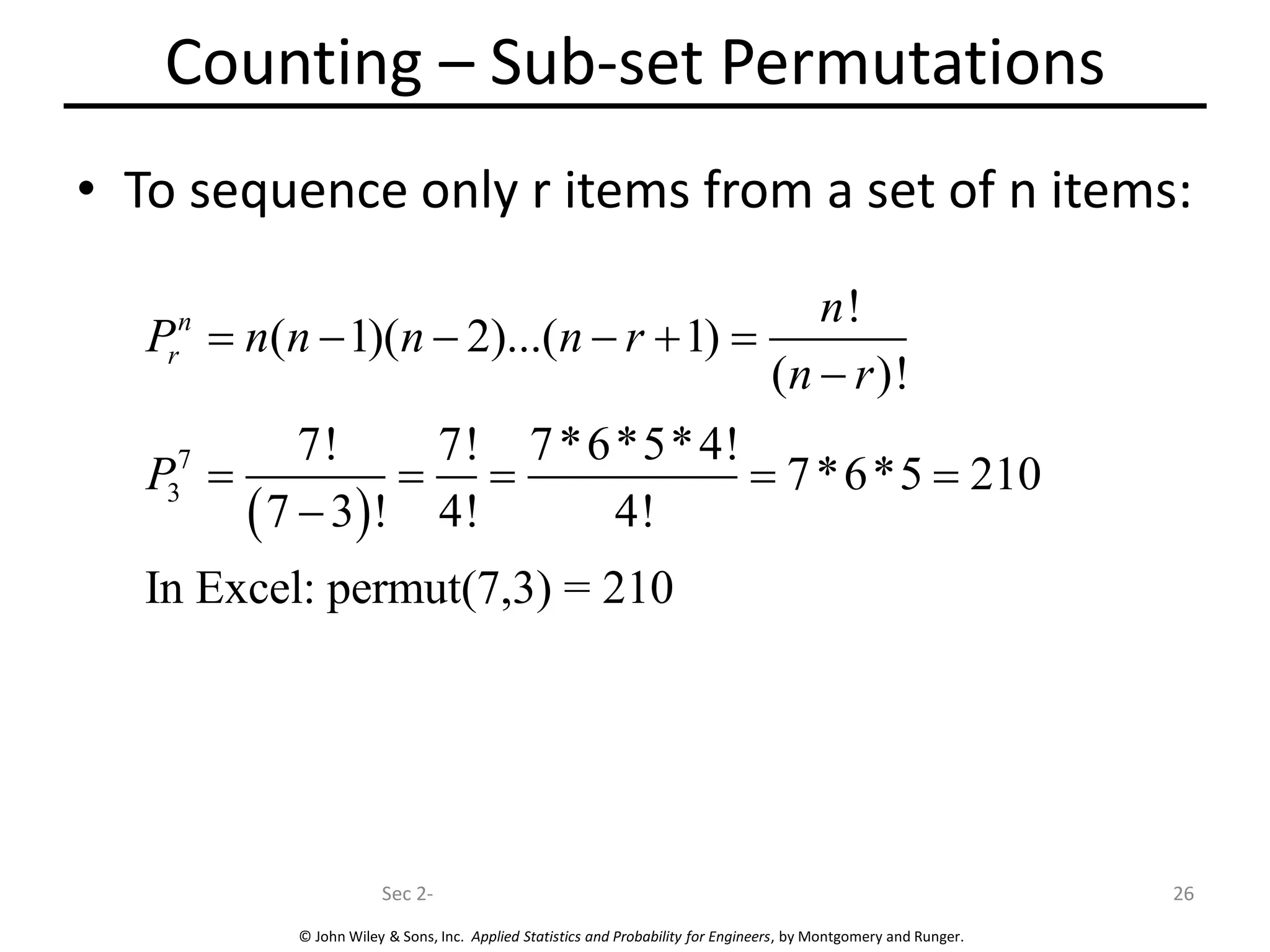

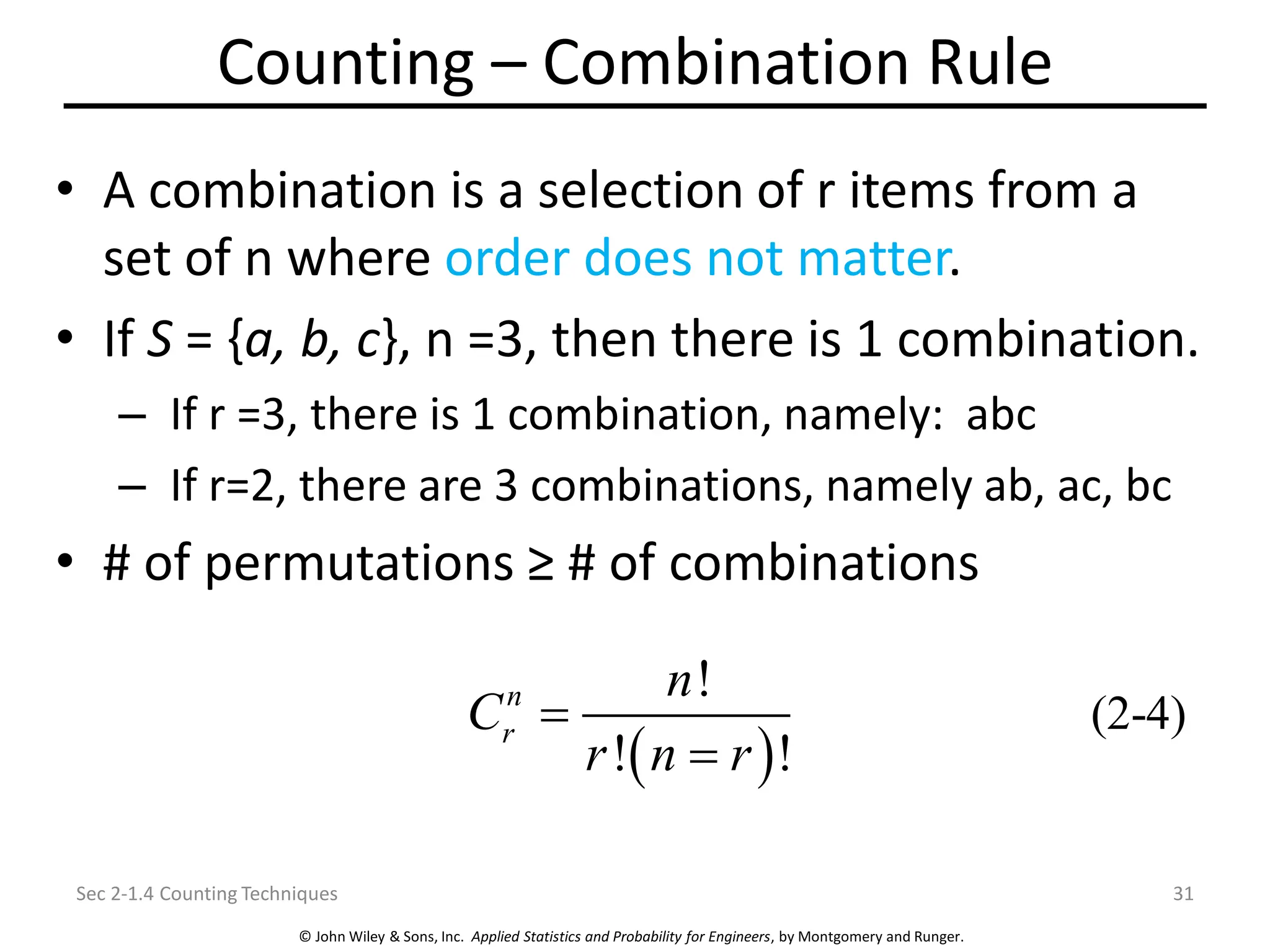

Chapter 2 focuses on probability concepts, including sample spaces, events, and probability rules. Key learning objectives encompass understanding random experiments, calculating probabilities of joint and conditional events, and applying counting techniques. The chapter emphasizes the application of models to analyze physical systems and the importance of recognizing randomness in various scenarios.

![© John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Applied Statistics and Probability for Engineers, by Montgomery and Runger.

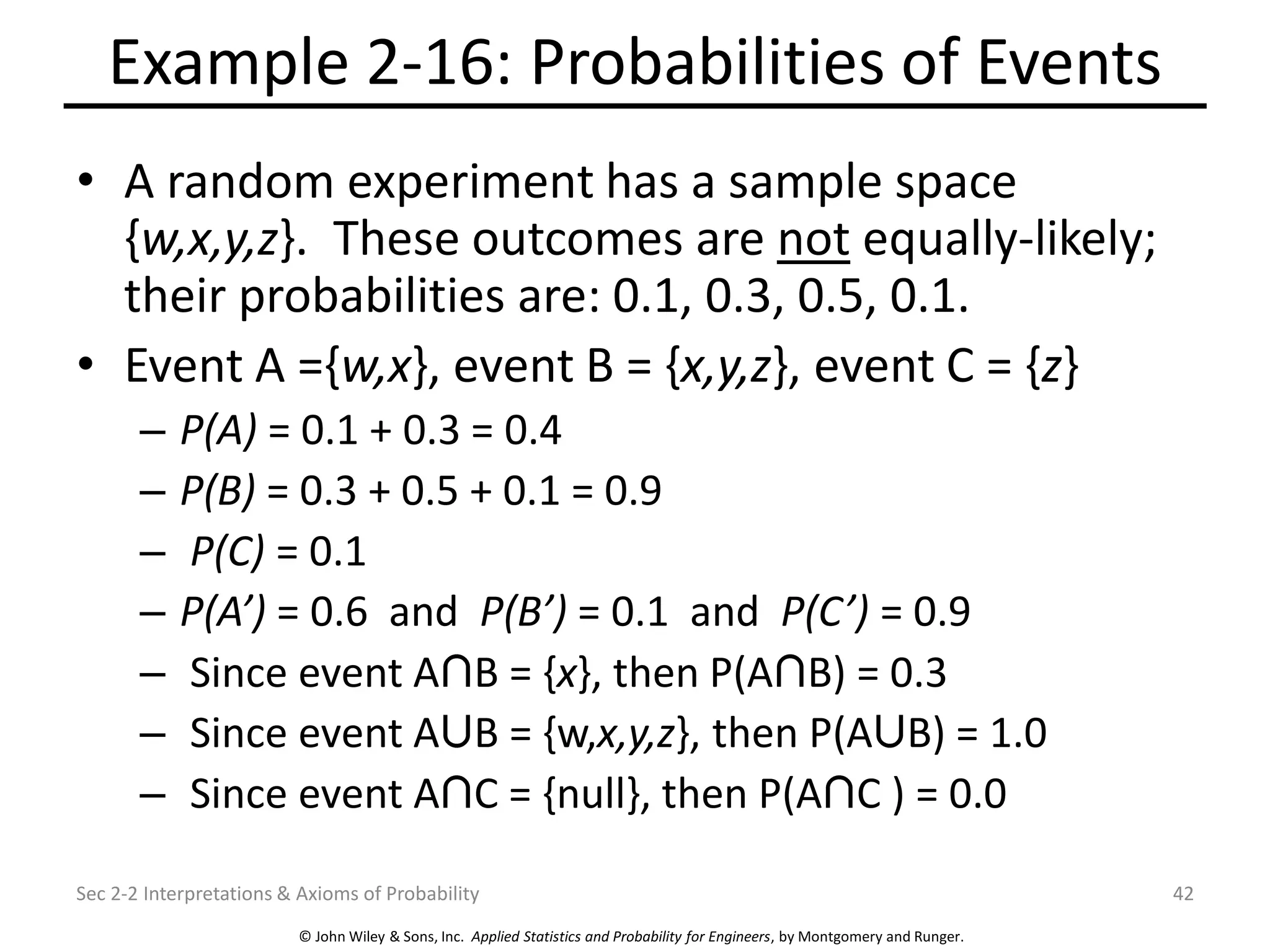

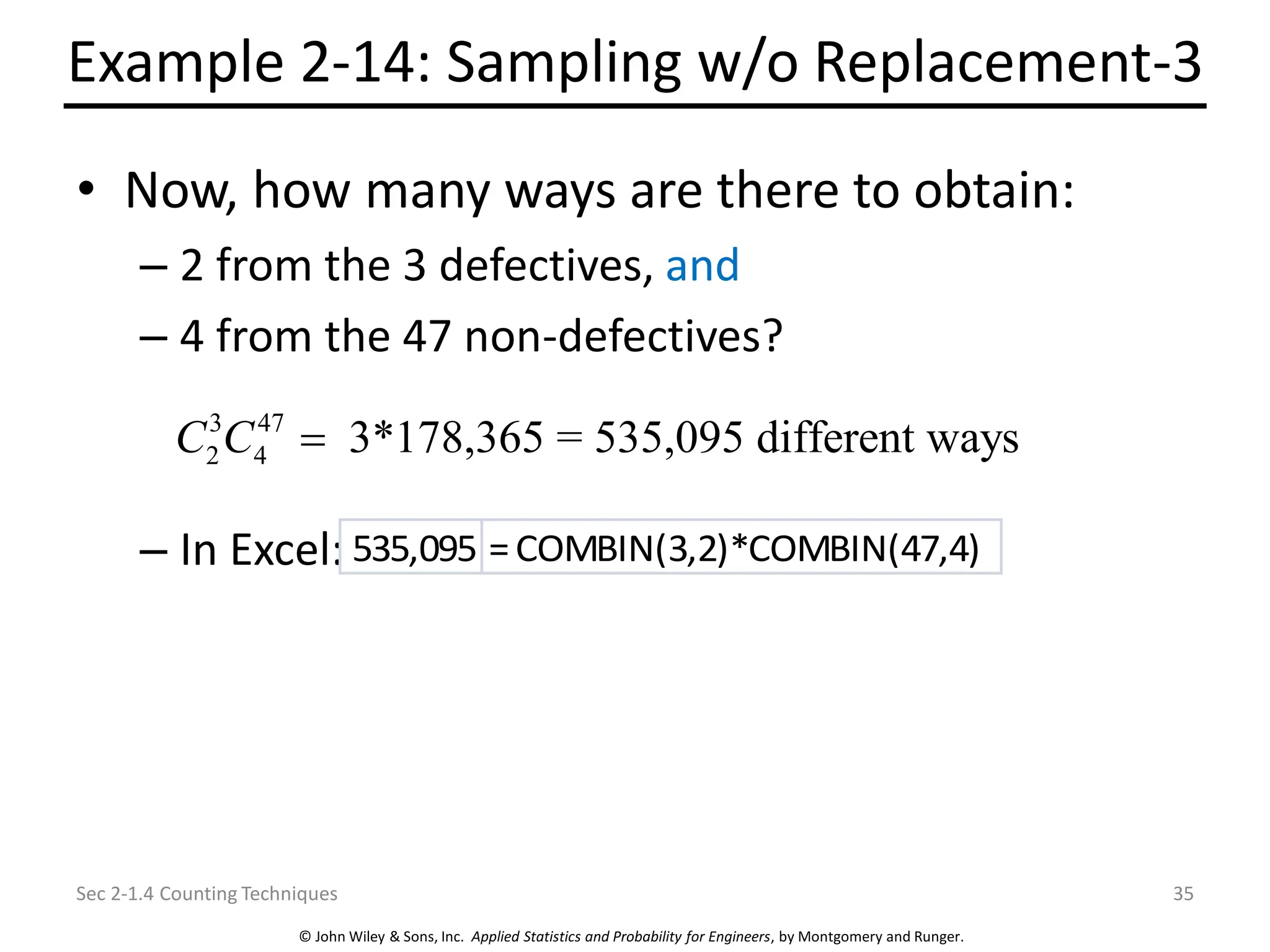

What Is Probability?

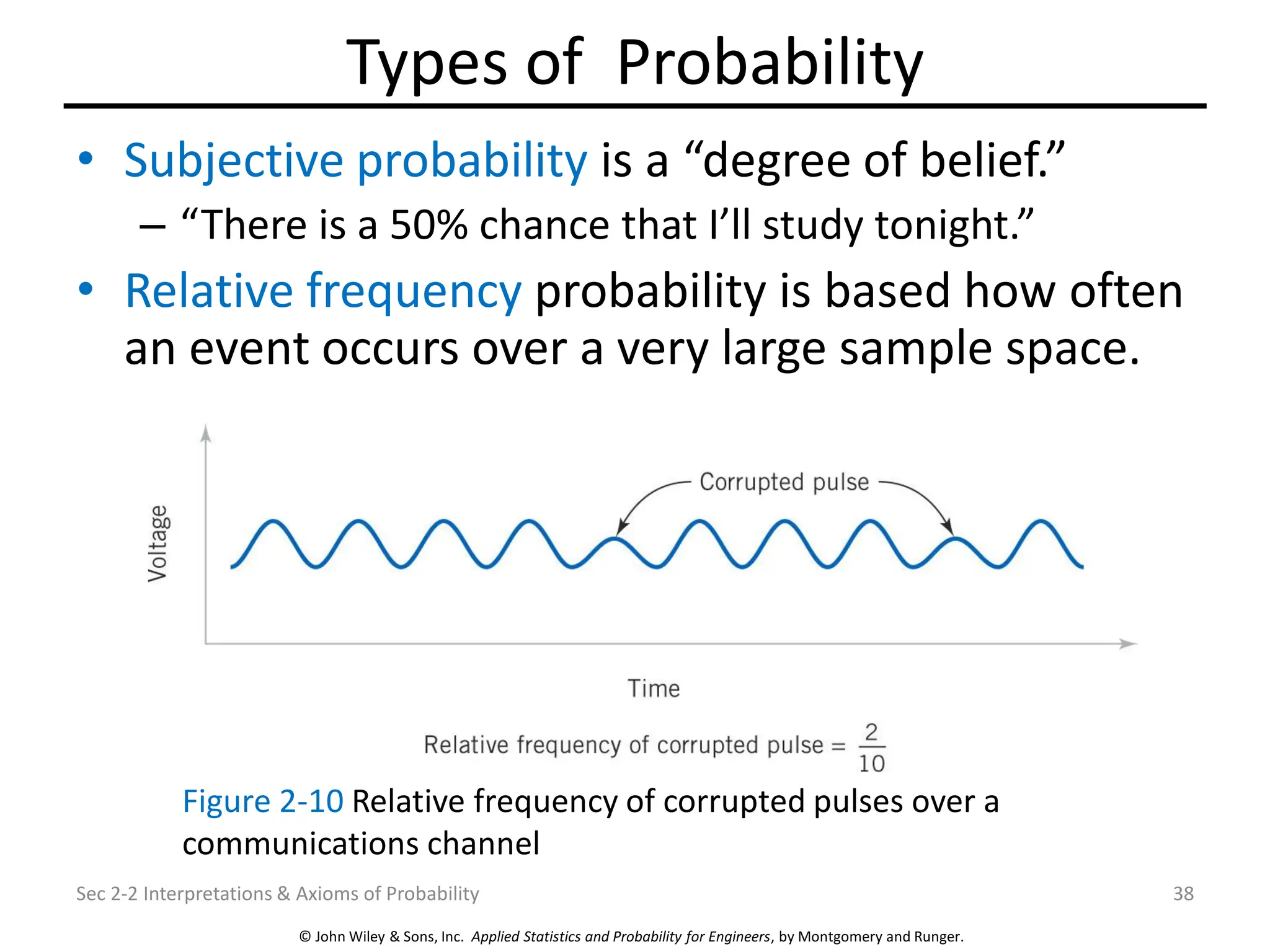

• Probability is the likelihood or chance that a particular

outcome or event from a random experiment will occur.

• Here, only finite sample spaces ideas apply.

• Probability is a number in the [0,1] interval.

• May be expressed as a:

– proportion (0.15)

– percent (15%)

– fraction (3/20)

• A probability of:

– 1 means certainty

– 0 means impossibility

Sec 2-2 Interpretations & Axioms of Probability 37](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter2probability-240312012254-ade7965a/75/Statistical-analysis-design-and-analysis-of-experiemnts-37-2048.jpg)